Abstract

Torture has been defined most precisely in legal contexts. Practitioners who work with torture survivors and researchers who study torture have frequently cited legal definitions, particularly those in the United States’ Torture Victims Relief Act, the United Nations Convention against Torture, or the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Tokyo. Few practitioners have operationalized these definitions and applied them in their practice. We describe how a New York City torture treatment clinic used a coding checklist that operationalizes the definitions, and present results. We found that in practice these definitions were nested; that using guidelines for applying the definitions in practice altered the number of cases meeting criteria for these definitions; and that the severity of psychological symptoms did not differ between those who were tortured and those who were not under any definition. We propose theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Keywords: torture definition, torture criteria, treatment, clinical practice, screening instruments

By any account, torture is one of the defining cultural phenomena of the first decade of the 21st century. Although torture was used by many governments and nongovernmental actors in the last half of the previous century (Engstrom & Okomura, 2004), the United States government’s response to the terrorist attacks of September 2001 brought the issue to the fore of public debate in nations where it had not been discussed for many years. With a long history of identifying potentially traumatic events and describing their psychological consequences, mental health professionals may be in a particularly good position to inform this discussion. The starting point for this discussion concerns what sort of experiences qualify as torture – that is, how definitions are applied.

In popular debate the issue of what experiences constitute torture may be seen as a primarily definitional problem, but how torture is operationalized has important ramifications at both personal and policy levels. Decisions such as who qualifies for governmental protections under political asylum statutes and whether particular interrogation practices by police and military officials are appropriate (or even legal) often hinge on whether an action or set of actions is deemed to be torture. Governmental bodies have often sought counsel from medical experts in order to answer such definitional questions (e.g., Keller, 2007), but two thirds of the medical and psychological research on torture fails to even define what is meant by the term “torture” (Green, Rasmussen, & Rosenfeld, 2010). The remainder apply either idiosyncratic definitions or reiterate international legal guidelines. The lack of rigor applied to definitions of torture has resulted in confusion, contradiction, and inconsistency among clinicians, researchers, and policy makers with regard to what constitutes torture.

Although definitional ambiguity makes it difficult to conclude what specific factors of torture are associated with particular outcomes, a substantial literature documents adverse sequelae. Numerous studies have demonstrated that torture is associated with profound and debilitating psychological as well as physical sequelae among forced migrant (e.g., Carlsson, Olsen, Mortensen, & Kastrup, 2006; Mollica, Wyshak, & Lavelle, 1987; Silove, Steel, McGorry, Miles, & Drobny, 2002; Shrestha et al., 1998), voluntary migrant (e.g., Eisenman, Gelberg, Liu, & Shapiro, 2003), and native-born populations alike (e.g., Başoğlu & Paker, 1995; Rasmussen, Rosenfeld, Reeves, & Keller, 2007). Because of the considerable mental health consequences of torture, developing a better understanding of this uniquely debilitating form of trauma thus is of clinical interest to mental health professionals globally. The treatment of survivors of torture can be traced to clinical reports concerning Holocaust survivors (Eitinger, 1964) and interventions designed for those persecuted by military juntas in Latin America in the 1970s (e.g., testimony therapy; Cienfuegos & Monelli, 1983). In the global North its roots are in the establishment of the Rehabilitation and Research Centre for Torture Victims in Denmark in the 1982. Many treatment programs in the North are funded by government legislation (e.g., the Torture Victims Relief Act, 18 USC 2340 (1), 1998) and by international nongovernmental organizations (e.g., the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture) that specifically target treating those who have suffered torture.

Agencies that provide funding for survivors of torture typically rely on one of three definitions of torture in their grantee specifications: the World Medical Association’s (WMA) Declaration of Tokyo of 1975, the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) of 1984, and the definition outlined in the United States’ Torture Victims Relief Act of 1998 (TVRA). In general, these definitions specify that for an abuse event to meet criteria as torture, it must be perpetrated by someone acting in a position of authority and must involve violent or psychologically manipulative acts. The WMA Declaration of Tokyo defines torture as the

deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons acting alone or on the orders of any authority, to force another person to yield information, to make a confession, or for any other reason (World Medical Association, 1975).

The UNCAT provides more specificity, defining torture as

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1984).

Although the United States is a signatory of the UNCAT, Federal legislation has offered a more detailed definition of what constitutes torture that is independent of the convention as well:

“torture” means an act committed by a person acting under the color of law specifically intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering (other than pain or suffering incidental to lawful sanctions) upon another person within his custody or lawful control (18 U.S.C. 23490(1) 1998).

This legislation further defined acts of “severe mental pain or suffering” as follows:

(A) the intentional infliction or threatened infliction of severe physical pain or suffering; (B) the administration or application, or threatened administration or application, of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or the personality; (C) the threat of imminent death; or (D) the threat that another person will imminently be subjected to death, severe physical pain or suffering, or the administration or application of mind-altering substances or other procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or personality.

In the United States TVRA legislation is administered by the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). In September of 2010, ORR provided further guidance on how to identify survivors of torture based on the United States Department of Justice’s most recent official opinion of the statute (see United States Department of Justice, 2004). The guidance was largely a restatement of 18 USC 2340, with the exception of the addition of a criterion that concerns the setting of the abuse:

At the time the acts were committed, was the applicant under the custody or control of the perpetrator (i.e., prison, holding facility, compound, camp, hospital, or school) (Office of Refugee Resettlement, 2010).

This elaboration introduced, for the first time, a requirement of specific physical settings in which acts can be considered torture. Correspondingly, acts that occur in other settings (e.g., a home that is surrounded by police) would not be considered torture.

How torture treatment programs apply these definitions to identify potential beneficiaries is unclear. Our experience is that classifying potential clients’ experiences as torture or not is a frequent source of frustration for torture treatment professionals (e.g., among members of the National Consortium of Torture Treatment Programs in the United States), and that many programs have only recently begun to systematically document how they go about doing this. Research on the practical application of such definitions may aid these programs, and may have legal implications insofar as documenting these criteria is important in forensic settings (e.g., asylum hearings). The current study is an attempt to begin such work by examining a year’s worth of pilot data applying the Torture Screening Checklist (TSCL), a narrative coding tool that classifies potential clients’ history as torture or not torture as specified by WMA, UNCAT, and TVRA. This work represents a real-world application of these criteria and was done to answer three research questions: (1) Can nonlegal professionals apply these criteria with minimal difficulty? (2) Are definitions of torture nested in practice (i.e., do cases that meet criteria for more restrictive definitions necessarily meet criteria for less restrictive definitions)? (3) Are alternative definitions of torture differentially associated with psychological sequelae within the torture treatment setting?

Methods

Procedure

The sample was drawn from archival records from the Bellevue/NYU Program for Survivors of Torture (PSOT), a torture treatment clinic located in a large public hospital in New York City. In order to comply with TVRA funding requirements the clinic began using the TSCL as part of its intake procedure in July 2009. The TSCL was completed primarily by mental health trainees, under the supervision of PSOT clinical staff, following the intake interview. Intake interviews involve asking prospective clients to describe the events that brought them to the treatment clinic, and are reviewed with senior clinicians in order to determine eligibility for clinical services. Following two months of training and pilot application by intake staff, clinic staff began recording the information collected using the TSCL. The sample is thus comprised of data from intake records between September 2009 and July 2010.

Sample

During the 10-month study period 190 potential clients presented for intake. The TSCL was completed for 165 (86.8%) of these individuals. Three-fifths of these 165 participants (n = 98, 59.4%) were men and the average age of the sample was 35.15 (SD = 10.10). Potential clients had immigrated to the United States from 42 countries, with 57 cases (34.5%) from countries in West Africa, 39 (23.6%) from East Asia, 20 (12.1%) from Central Africa, 13 (7.9%) from South Asia, 11 (6.7%) from Eastern Europe, and 24 (14.5%) from other regions (one case was missing country of origin data). All participants indicated in their interview that they had either applied or planned to apply for asylum at intake.

Intake interviews were conducted by 19 different mental health practitioners, the vast majority (n = 180, 94.7%) of whom were trainees in psychology (doctoral students in psychology) supervised by four senior psychologists (mean number of years working at the clinic = 5.6; SD = 5.1). Other intake evaluations were completed by psychiatry residents (n = 4, 2.1%), psychiatrists (n = 3, 1.6%), or the senior psychologists themselves (n = 2, 1.1%), and intake clinician was missing data for one case.

Measures

The first author created the TSCL specifically to operationalize WMA, UNCAT, and TVRA definitions of torture. The TSCL was designed to be completed by medical, mental health, and social work professionals to systematically identify torture-relevant information from narratives. The TSCL is comprised of items for each nominal, adjectival, and adverbial clause in each of the definitions. For example, the WMA phrase “deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction” corresponds to three yes/no items that elicit a judgment about whether the abuse described was “deliberate,” “systematic,” and “wanton.” The TSCL also elicits a brief description of the abuse, including the location where the abuse occurred, making it consistent with the September 2010 guidance from ORR on applying the TVRA definition. As a coding instrument, the TSCL is not a self-report questionnaire (i.e., filled out by a potential client) or a structured interview, but rather a checklist to be used for writing an assessment report. Thus, coding was based on the criterion items that were spontaneously articulated during the intake interview (rather than attempting to disentangle items that were definitively not present from those that were simply “missing”). The current manuscript represents the first systematic evaluation of the utility of the TSCL in a clinical setting.

Included in the intake assessment package were two psychological symptom measures, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; Mollica et al., 1992) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). All participants completed the DSM-IV PTSD symptom portion of the HTQ, a 16-item scale measuring severity of PTSD symptoms described in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The HTQ asks participants to rate how much each of 16 PTSD symptoms bothered them in the past week using a 4-point frequency scale, where 1 corresponds to “not at all” and 4 “extremely.” Studies in several populations have utilized a cut-off score of 2.5 to identify “clinically significant” PTSD symptoms (Mollica et al., 1992). A review of instruments used in studies of refugees (Hollifield et al., 2002) noted that the HTQ has been found to have the strongest evidence for reliability and validity in multiple studies across multiple traumatized populations.

The 20-item CES-D measures both negative and (the lack of) positive affect associated with depression using a 4-point symptom frequency scale (range of possible scores 0 to 60). In community samples the cut-off 16 has been suggested for identifying “clinically significant” depression (Roberts & Vernon, 1983). The CES-D has been used internationally (González-Fortaleza, Jiménez-Tapia, Ramos-Lira, & Wagner, 2008) and in research in ethnically diverse urban samples as well (Grunebaum, Oquendo, & Manly, 2008; Miller et al., 2004). In the current sample not all participants had complete data from screening measures: 144 cases had complete data for HTQ scores and 126 for CES-D scores.

Because the data used for this study was archival information collected in the normal course of treatment for clients and potential clients in the clinic, informed consent was not sought. The use of this data for research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York University School of Medicine.

Results

Table 1 presents the frequency of criteria included in the WMA, UNCAT, and TVRA definitions. The first criterion, a history of abuse perpetrated by someone acting as an authority in a given setting, is a “gateway” criterion insomuch as the absence of this criterion renders the rest of the criteria moot. We thus presented the number of cases that met this criterion in the first row of Table 1 and calculated all percentages for other criteria based on the base rate of this gateway criterion. In other words, because 132 of the 160 complete cases met the abuse criterion, we present proportions of subsequent criteria based on these 132 cases instead of the full 160. Also of note is the indication of missing data in Table 1. As the purpose of presenting results in Table 1 is to report on the clinical application of the TSCL, we feel it is important to include all data from the 132 and not exclude cases because of missing information on a few criteria. We report the number of missing cases to note criteria that may have been difficult to complete (and therefore may be in need of better specification in subsequent versions of the TSCL).

Table 1.

Torture criteria

| Definition | Criteria | N (%) | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gateway criterion | Abuse by “authority” | 132/165 (80.0) | |

| WMA, UNCAT, TVRA | Suffering | 132/132 (100.0) | |

| WMA, UNCAT, TVRA | Deliberate | 131 (99.2) | |

| WMA | Systematic | 115 (87.1%) | 2 |

| WMA | Wanton | 115 (87.1%) | 5 |

| WMA, UNCAT, TVRA | Coercive purpose | 129 (97.7) | |

| UNCAT, TVRA | Participation of government official | 123 (93.2) | |

| UNCAT, TVRA | Extra-legal | 130 (98.5) | 2 |

| TVRA | Harm for “long period of time” | 127 (96.2) | |

| Harm from at least one: | |||

| TVRA | “Severe suffering” | 121 (91.7) | |

| TVRA | “Threatened infliction” | 82 (62.1) | 8 |

| TVRA | “Administration of drugs” | 14 (10.6) | 11 |

| TVRA | “Death threats” | 57 (43.2) | 10 |

| TVRA | “Threats made against others” | 57 (43.2) | 10 |

| Additional ORR guidance for TVRA | Setting under control of authority | 95 (71.7) |

Notes. WMA = World Medical Association; UNCAT = United Nations Convention Against Torture; TVRA = Torture Victims Relief Act (USA); ORR = Office of Refugee Resettlement (USA).

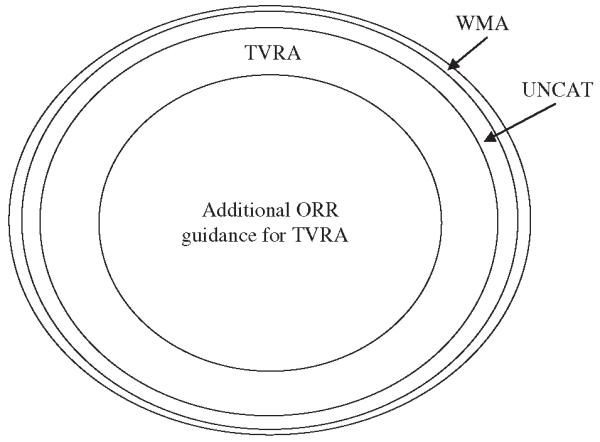

Among the 132 cases that met the abuse by authority gateway criterion, 131 (99.2%) met criteria for the WMA definition of torture, 128 (97.0%) met criteria for UNCAT, and 124 (93.9%) met criteria for TVRA. When ORR guidance was applied, only 92 (69.7%) of 132 cases fulfilled all of the requirements for classifying their experiences as torture. In other words, this additional requirement resulted in a 24.8% reduction among those originally classified under TVRA. When we examined whether cases met criteria for torture under multiple definitions, we found that the pattern was such that cases that qualified as torture under later and more specific definitions also did so for the earlier definitions. This overlap is presented graphically in the Venn diagram presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overlap in torture definitions. WMA = World Medical Association; UNCAT = United Nations Convention Against Torture; TVRA = Torture Victims Relief Act (USA); ORR = Office of Refugee Resettlement (USA).

Types of abuse reported by applicants were recoded to fit categories specified by Human Rights Information and Documentation Systems (HURIDOCS). HURIDOCS is an internationally-developed documentation system that provides standard codes for various phenomena related to human rights abuses (HURIDOCS, 2010). This coding system divides abuse into several categories. Frequencies of six commonly reported categories in the torture literature are presented in Table 2 as they intersect with the four torture classifications. Cells in Table 2 represent the number of cases that meet criteria for the referenced torture definition that included the referenced abuse. Frequencies presented here show that most abuse types were consistent with WMA and UNCAT definitions, but that there was a clear separation in the percentages of abuse types that are parts of torture experiences with the application of the more restrictive criteria. For example, the percentage of cases involving beatings that qualified as torture were similar using WMA and UNCAT criteria, but were substantially lower for TVRA with ORR guidance, while for electrocution the percentages were similar across all torture categories.

Table 2.

Selected abuse types and torture definitions

| Total | WMA | UNCAT | TVRA | Additional ORR guidance for TVRA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beating | 112 | 108 (96%) | 107 (95%) | 105 (94%) | 95 (85%) |

| Burning | 7 | 6 (86%) | 6 (86%) | 5 (71%) | 3 (43%) |

| Sexual assault | 37 | 33 (89%) | 32 (97%) | 31 (84%) | 26 (70%) |

| Electrocution | 20 | 20 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 19 (95%) |

| Forced postures | 9 | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 9 (100%) | 8 (89%) |

| Death threats | 56 | 52 (93%) | 52 (93%) | 52 (93%) | 38 (68%) |

Notes. WMA = World Medical Association; UNCAT = United Nations Convention Against Torture; TVRA = Torture Victims Relief Act (USA); ORR = Office of Refugee Resettlement (USA).

The sample mean for the HTQ was 2.61 (SD = 0.60) and for CES-D, 33.46 (SD = 11.66); 137 (72.1%) met the HTQ cut-off of 2.5, and 182 (95.8%) met the CES-D cut-off score of 16. In order to examine associations between torture criteria and psychological symptom severity and functional impairment, independent sample t-tests were used to determine whether mean scores on the HTQ and CES-D differed between individuals who fulfilled the four different criteria for identifying torture (WMS, UNCAT, TVRA, and TRVA/ORR). T-tests revealed that mean HTQ and CES-D scores were not significantly different between torture and non-tortured cases for any torture definition. Tests for differences between scores for those with WMA/UNCAT/TVRA (collapsed because of small cell sizes for those with only WMA and UNCAT definitions) and TVRA with the setting criterion showed no significant differences either. When we examined categorical associations between torture (yes/no) and psychological scores using clinical cutoffs (HTQ = 2.5 and CES-D = 16) using chi-square and Fisher’s exact test, the results were similar: no significant differences in rates of probable PTSD or major depression.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first published study to systematically document and report each criterion of commonly used torture definitions in a practice setting, and thus the first to assess what are potentially important contextual data that have routinely been ignored in the research literature (Green et al., 2010). Although definitions of torture may have theoretical differences (e.g., a close reading of WMA’s definition reveals that it does not specify governmental authorities as perpetrators), we found that in practice they were nested, with WMA and UNCAT criteria sets being the most inclusive (and essentially duplicative), and the TVRA criteria set slightly more restrictive. The consistency of criteria sets is reflected in consistency of WMA and UNCAT criteria with the gateway criterion, abuse by an authority. Somewhat less consistent with the gateway criterion are those TVRA criteria that distinguish TVRA from WMA and UNCAT.

Also notable is that applying the criterion for specific torture settings as suggested by ORR in their September 2010 guidance memo reduced the number of torture cases by a quarter. Although applied retrospectively, this finding suggests that this particular piece of contextual information is more important than the contextual data included in the core criteria of torture definitions. That this critical information be judged important to the application of a definition that does not explicitly include it seems odd. The ORR settings criterion essentially asks those making decisions at torture treatment centers to evaluate the criterial features of a textual definition of torture using a criterion external to the definition itself. Our analysis shows that this external criterion turns out to be very powerful indeed. Although applying such second-order features is not unheard of in taxonometric systems employed by mental health professionals (e.g., psychologists often use such associated features in diagnosing PTSD; Young, 1995), this practice will likely result in decisions that appear inconsistent with the definition they reference. It is not yet clear whether ORR will indeed require a strict interpretation of the language used in their guidance, or would emphasize “the custody or control of the perpetrator” over the specific settings referred to in the parenthetical clause that follows it. If the control of the perpetrator is the important factor, a simple change of the guidance from “i.e.” to “e.g.” is in order.

That we found no differences between tortured and non-tortured cases using the severity of psychological symptoms or diagnostic cut-off scores is best explained by the setting in which the TSCL was applied. Among those who did not report abuse by authority figures many did report substantial abuse at the hands of others and considerable stressors related to migration and legal status. That we found no differences between those meeting criteria for the different definitions of torture is consistent with research by Başoğlu regarding differences in torture statues (Başoğlu, Livanou, & Crnobaric, 2007) that found that psychological distress was not associated with more or less restrictive statutes. However, the finding that the setting criterion did not distinguish levels psychological suffering is inconsistent with theoretical work by Başoğlu that posited that the distinguishing psychological element in the severity of torture is control over individual (Başoğlu, 2009; Başoğlu et al., 2007). It may be that ORR’s setting criterion is an unreliable measure of control over individual, and perhaps that a more multifaceted measure would capture variance in psychological sequelae. In any case, a sample characterized by displacement is likely to include multiple stressors that confound attempts to isolate the effects of particular torture criteria.

Missing data on certain criteria (presented in Table 1) reflect challenges to using the TSCL in its current form. Although revisions are underway to clarify items for which missing data were a problem, we expect that some confusion is inherent to askinghealthcare professionals to apply what are essentially legal definitions to their work. Although missing data was not a large problem for the criterion relating to whether or not the abuse was consistent with legal statutes within the countries in which it occurred, several supervisors reported that trainees found it confusing. One can easily see why this was so: penal codes of various countries are well outside the scope of mental health professionals’ training, being largely irrelevant for treatment. However, given that they are a key criteria of UNCAT and TVRA definitions, they are not irrelevant for funding treatment, and thus must be considered by torture treatment staff (in the current case, these staff were experienced supervisors). With knowledgeable staff available, we conclude that it is indeed feasible for healthcare professionals to apply torture criteria with minimal difficulty.

The current protocol did not include any assessment of the validity of definitions vis-à-vis participants’ experiences of torture, and therefore we do not have data supporting the use of one definition over another. We can say that as WMA and UNCAT definitions seem to be largely consistent in practice and as the language in UNCAT is more specific, we feel that using WMA in a clinic that uses UNCAT probably does not add any utility. In addition to the lack of data on definitions’ validity, the current study was limited by not including data on the interrater reliability of the TSCL. Although the 95–100% interrater agreement was reported for a previous version (Rasmussen et al., 2007), we cannot say these rates would be replicated for the current one. Moreover, as there exist no good measures of false claims of torture or malingering that can easily be applied in a multicultural context (such as a torture treatment setting), we cannot assess the veracity of all participants’ reports. This lack is a detriment to our entire field, and the development of such measures would be particularly useful in interactions with forensic settings.

We created a screening measure in order to systematically document abuse narratives according to criteria of major definitions of torture. That we were able to do so using supervised trainees with minimal confusion is notable, as it suggests that, with the exception concerning knowledge of penal codes in countries of origin, for practical purposes such legal decisions are not difficult to make. We encourage our colleagues to engage in such practice-based research and would gladly share our revised tool with any who contact us. The clearer the torture treatment field is about what torture is – and what torture is not – the better able we will be to fund services and inform public debate.

Acknowledgments

The research described was supported in part by Award Number K23HD059075 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (USA) to Andrew Rasmussen. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Başoğlu M. A multivariate contextual analysis of torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatments: Implications for an evidence-based definition of torture. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:135–145. doi: 10.1037/a0015681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başoğlu M, Livanou M, Crnobaric C. Torture vs. other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment: Is the distinction real or apparent? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:277–285. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başoğlu M, Paker M. Severity of trauma as predictor of long-term psychological status in survivors of torture. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson JM, Olsen DR, Mortensen EL, Kastrup M. Mental health and health-related quality of life: A 10-year follow-up of tortured refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:725–731. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243079.52138.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cienfuegos AJ, Monelli C. The testimony of political repression as a therapeutic instrument. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1983;53:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Cunningham JD. Patterns of symptomatology and patterns of torture and trauma experiences in resettled refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;31:555–565. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman DP, Gelberg L, Liu H, Shapiro MF. Mental health and health-related quality of life among adults living in the United States with previous exposure to political violence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:627–634. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitinger L. Concentration camp survivors in Norway and Israel. Universitetsforlaeget; Oslo, Norway: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom DW, Okomura A. A plague of our time: Torture, human rights, and social work. Families in Society. 2004;85:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- González-Fortaleza C, Jiménez-Tapia J, Ramos-Lira L, Wagner FA. Aplicación de la escala de depresión del Center for Epidemiological Studies en adolescentes de la Ciudad de México [Application of the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in adolescents from Mexico City] Salud Pública de México. 2008;50:292–299. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D, Rasmussen A, Rosenfeld B. Defining torture: A review of 40 years of health science research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:528–531. doi: 10.1002/jts.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Oquendo MA, Manley JJ. Depressive symptoms and antidepressant use in a random community sample of ethnically diverse, urban elder persons. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;105:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Warner TD, Lian N, Krakow B, Jenkins JH, Kesler J, Westermeyer J. Measuring trauma and health status in refugees: A critical review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:611–621. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HURIDOCS 2010 Retrieved from http://www.huridocs.org/

- Keller A. Testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Hearing on U.S. Interrogation Policy and Executive Order 13440. United States Senate; Washington, DC: Sep 25, 2007. 2007. Retrieved from http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/testimony-2007-09-25.html. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DK, Malmstrom TK, Joshi S, Andresen EM, Morley JE, Wolinsky FD. Clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms in community-dwelling middle-aged African Americans. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:741–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and post traumatic stress disorder in refugees. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders. 1992;180:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Wyshak G, Lavelle J. The psychosocial impact of war trauma and torture on Southeast Asian refugees. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1567–1572. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Refugee Resettlement . Survivors of torture program eligibility determination tool. Office of Refugee Resettlement, Torture Survivors Program; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. 1984 Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/cat.html.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Vernon SW. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Its use in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:41–46. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Rosenfeld B, Reeves K, Keller AS. The effects of torture-related injuries on psychological distress in a Punjabi Sikh sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:734–740. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D, Steel Z, McGorry P, Miles V, Drobny J. The impact of torture on post-traumatic stress symptoms in war-affected Tamil refugees and immigrants. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43:49–55. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.29843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha NM, Sharma B, Van Ommeren M, Regmi S, Ramesh M, Komproe I, de Jong JTVM. Impact of torture on refugees displaced within the developing world: Symptomatology among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. JAMA. 1998;280:443–448. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.443. United States Congress. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Justice Legal standards applicable under 18 USC 2340-2340A. Office of Legal Counsel. 2004 retrieved from http://www.usdoj.gov/olc/18usc23402340a2.htm.

- World Medical Association . Declaration of Tokyo. Adopted by the World Medical Association; Tokyo, Japan: Oct, 1975. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Young A. The harmony of illusions. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1995. [Google Scholar]