Abstract

Most scoring assays for yeast prions are dependent on specific genetic markers and constructs that differ for each prion. Here, we describe a simple color assay for the [URE3] prion that works in the 74D-964 strain frequently used to score the [PSI+] prion. Although this assay can only be used to score for [URE3] in the [psi−] version of the strain, it makes it easier to examine the effects of host mutations or environmental changes on [URE3] or [PSI+] using a color assay in the identical genetic background.

Keywords: Color assay, [URE3], [PSI+], identical genetic strain

Introduction

Prions, the infectious proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases in mammals (Prusiner, 1982), are responsible for protein-based heritable traits in lower eukaryotes (Wickner, et al., 1999). A variety of prions are known in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These include [PSI+] (Wickner, et al., 1995), [PIN+] (Derkatch, et al., 1997; Sondheimer and Lindquist, 2000), [URE3] (Wickner, et al., 1995), [SWI+] (Du, et al., 2008), [OCT+] (Patel, et al., 2009), [MCA1] (Nemecek, et al., 2009), [MOT3+] (Alberti, et al., 2009), [GAR+] (Brown and Lindquist, 2009), [ISP+] (Rogoza, et al., 2010) and [NSI+] (Saifitdinova, et al., 2010). The proteins responsible for these prions perform distinct functions in yeast, although several of them are transcription regulators. Ure2 (associated with [URE3]) governs nitrogen catabolite repression, while Swi1 (associated with [SWI+]), Cyc8 (associated with [OCT+]), Mot3 (associated with [MOT3+]) and Sfp1 (associated with [ISP+]) are general transcription repressors. Each prion requires its own special set of markers to facilitate ease in scoring for prion presence. This difficulty has inhibited experimenters from determining in an isogenic background, if effects detected on one prion also affect other prions.

Two of the most widely studied yeast prions are [PSI+] and [URE3]. [PSI+] is the prion form of the translational release factor, Sup35 (Wickner, et al., 1995). When in the prion form the activity of Sup35 in translational termination is compromised so [PSI+] is detected as readthrough of nonsense mutations. For example, a widely used assay for [PSI+] involves read through of a nonsense codon in the ade1-14 allele which results in growth on Ade and white colony color on YPD in the presence of the prion, while non prion [psi−] cells are unable to grow on Ade and are red on YPD due to the accumulation of a red pigment (Chernoff, et al., 1995; Inge-Vechtomov, et al., 1988). The advantage of the color assay over growth on Ade is that cells lacking the prion can easily be detected without replica-plating. This is especially useful in experiments examining the loss of the prion. The color assay also allows the easy distinction between different forms of the prion called variants (Derkatch, et al., 1996; Schlumpberger, et al., 2001).

[URE3] is the prion form of the Ure2 protein which is a transcriptional repressor for genes involved in nitrogen metabolism like GLN3 and GAT1 (Cooper, 2002). A variety of assays have been developed to score for [URE3] that require specific markers. One of the first assays to score for [URE3] involved the uptake of ureidosuccinate (USA). In [URE3] cells, when the activity of Ure2 is compromised, DAL5 which is activated by Gln3, is turned on, allowing cells to take up USA in the presence of ammonium ions (Aigle and Lacroute, 1975; Wickner, 1994). Thus, [URE3] can be detected by the ability to grow on media containing USA, while [ure-o] cells cannot grow on USA media. Although this method is a simple growth assay, it only works in ura2 mutant cells that cannot synthesize USA and detection of [ure-o] cells requires replica-plating. [URE3] can also be detected in wild type URA2 cells with color or growth markers under control of the DAL5 promoter (Brachmann, et al., 2006; Schlumpberger, et al., 2001). Additionally, a feeding assay for [URE3] has been described in which no special markers are required. In this assay, the presence of [URE3] allows Ura− yeast to feed on the excreted uracil produced by [URE3] cells in the presence of excess USA (Moriyama, et al., 2000). However, this method is inconvenient for large scale experiments.

Here we describe a simple new color assay to score for the presence of the [URE3] prion in the 74D-694 strain that has been widely used to study and score for [PSI+]. Although it is not possible to score for both [PSI+] and [URE3] simultaneously with this assay, it is very useful because it makes it easy to compare the effects of other genes or environmental factors on [PSI+] and [URE3] in the identical genetic background. Another advantage of this method is that the presence, as well as absence, of both the [PSI+] and [URE3] prions can each be detected with a color assay, facilitating the scoring of factors that influence the appearance as well as loss of the prions.

Materials and methods

Yeast were grown on standard media (Sherman, et al., 1986) at 30oC. Cells were cured of prions on YPD + 5mM guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) (Eaglestone, et al., 2000) and were made [rho0] on YPD + 0.05 mg/ml ethidium bromide (YPD + EtBr) (Goldring, et al., 1970). Markers were scored on selective synthetic dextrose media.

SY80 ([PSI+][PIN+]) and SY84 ([psi−][pin−]) were kindly supplied by T.R.Serio and are derivatives of 74D-694 ade1-14, trp1-289, his3-del200, ura3-52, leu2-3, 112 with endogenously GFP tagged SUP35 (Satpute-Krishnan and Serio, 2005). SY80 was cured of [PSI+] and the resulting [psi−][PIN+] derivative and SY84 were made into [rho0]. [URE3][psi−][pin−] donor strains were obtained by growing BY241 [URE3] [PIN+] [PSI+] (ura3, leu2, trp1, PDAL5-ADE2, kar1-1) (kindly supplied by R.B.Wickner) on medium with 5mM GuHCl. Colonies were checked for the presence of [URE3] and the loss of [PSI+] and [PIN+] by mating to cells expressing diffuse Ure2-GFP (to look for dots), and Sup35NM-GFP and Rnq1-GFP (to look for diffuse fluorescence) respectively.

For cytoduction (Conde and Fink, 1976), [PRION+] kar1-1 donors mated for 6 hrs with [prion−] recipients on YPD were subcloned on complex media containing 3 % glycerol (YPG). The smaller colonies that had recipient markers were the cytoductants.

Results

Endogenous tagging of Sup35 with GFP causes a slight lightening of the ade1-14 associated red color

Normal yeast colonies are white. The 74D-694 strain, which contains a [PSI+] suppressible ade1-14 marker, has been frequently used to facilitate the study of the [PSI+] prion. Since mutations in ade1 cause the build up of a red pigment via the adenine biosynthesis pathway, the [psi−] version of 74D-694 is red, while the presence of [PSI+] which promotes read through of the ade1-14 nonsense mutation returns cells to the normal white color (Chernoff, et al., 1995; Inge-Vechtomov, et al., 1988).

When the endogenous Sup35 protein in 74D-694 [psi−] was tagged with GFP (Satpute-Krishnan and Serio, 2005), we noticed that the red color associated with this ade1-14 strain became lighter (Figure 1A). Thus while the tagged Sup35 has been shown to retain function and folds in the prion or non-prion form (Satpute-Krishnan and Serio, 2005), we hypothesize that the tag compromises Sup35 function, causing a slight read through of the ade1-14 nonsense mutation in [psi−] cells with diffuse Sup35-GFP.

Figure 1. Scoring for [URE3] in ade1-14 [psi−] yeast with endogenously GFP tagged SUP35.

A. SUP35-GFP leads to lighter red color in 74D-694. [PIN+] and [pin−−] 74D-694 and 74D-694 SUP35-GFP were spotted on YPD. Pictures were taken after 4 days of incubation at 30°C (left panels) or an additional 5 days of incubation at 4°C (right panels). All cells shown are [psi−]. B. [URE3] darkens the red color of 74D-694 SUP35-GFP. When [URE3] was cytoduced in [PIN+] or [pin−] 74D-694 SUP35-GFP, the color changed from the light red associated with [ure-o] to a darker red for [URE3] cytoductants. All 11 independent [URE3] cytoductants obtained looked identical to the one shown.

Cytoducing [URE3] into [psi−] cells with endogenous Sup35 tagged with GFP darkens their red color

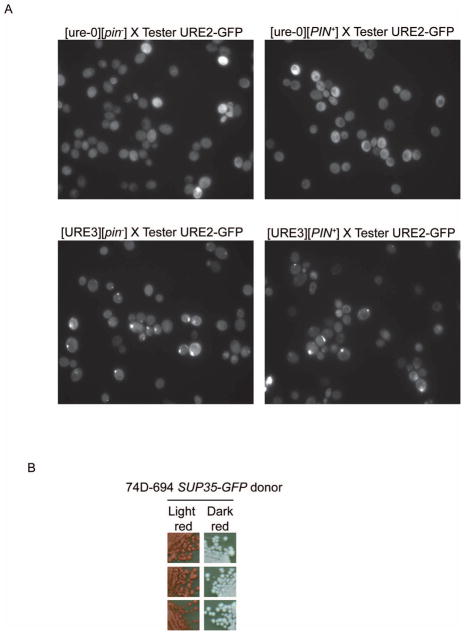

Curiously, when the lighter red Sup35-GFP tagged [psi−] derivative of 74D-694 was cytoduced with [URE3], the color was restored to deep red (Figure 1B). This effect was specific to [URE3] as the prion form of Rnq1, [PIN+], did not cause the Sup35-GFP tagged [psi−] 74D694 strain to become darker. All 11 [URE3] ([pin−] or [PIN+]) cytoductants examined were dark red and were verified to be [URE3] by the appearance of punctate fluorescence when crossed to a [ure-o] Ure2-GFP tester strain (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Confirmation assays for [URE3].

A. Scoring for [URE3] using Ure2-GFP. To confirm the red color assay for [URE3], the dark red presumed [URE3] cytoductants shown in Figure 1 were mated to [ure-o] cells carrying a plasmid expressing Ure2-GFP. All 11 dark red [URE3] (bottom), but not the presumed light red [ure-o] (top), diploids showed the formation of punctate dots indicative of the [URE3] prion aggregation. B. Scoring for [URE3] using the PDAL5-ADE2 assay. The dark red [URE3] cytoductants and the light red [ure-o] cells, shown in Figure 1B, were cytoduced into [ure-o] BY241 and spotted on YPD. BY241 contains PDAL5-ADE2 which is activated by Gln3. Ure2 represses Gln3, and thus PDAL5, to prevent Ade2 synthesis in [ure-o] cells resulting in a red color on YPD. However, [URE3] cells, in which activation of Gln3 allows synthesis of Ade2, are white. All [ure-o] cytoductants (20 obtained, 3 shown) were red and all [URE3] cytoductants (19 obtained, 3 shown) were white.

Since [PSI+] causes ade1-14 mutant yeast to be white, it should be noted that this [URE3] scoring assay only works in 74D-694 SUP35-GFP [psi−], and not [PSI+] cells,.

Loss of [URE3] in [psi−] cells with endogenous Sup35 tagged with GFP lightens their red color

To see if loss of [URE3] would restore the cells to the lighter red color, a [URE3] [PIN+] Sup35-GFP tagged 74D-694 derivative was subcloned on 5 mM GuHCL. Twenty-one subclones were picked and patched on YPD: 12 were light red suggesting loss of [URE3]; 9 were dark red suggesting the continued presence of [URE3]. All 21 clones were crossed to the [ure-o] URE2-GFP tester and all diploids from light red derivates lacked fluorescent foci, while all the diploids from dark red derivatives had foci (not shown). In addition, three dark red and three light red colonies were also scored for [URE3] by using them as donors to cytoduce a recipient strain in which [URE3] turns on the expression of the ADE2 gene under the control of the DAL5 promoter leading to a white colony color (Schlumpberger, et al., 2001). Over 6 cytoductants were examined for each donor. All cytoductants from the dark red donors were [URE3] (white) and all from the light red donors were [ure-o] red (Figure 2B).

Discussion

While normal yeast is white in color, certain mutations in the adenine biosynthesis pathway (e.g. ADE1 and ADE2 mutations) lead to the accumulation of a modified form of the intermediate (P-ribosylamino imidazole, AIR) that imparts a red colony color (Figure 3). The transcriptional activators Gln3 and Gat1 have been shown to be involved in the regulation of genes in the adenine biosynthesis pathway (ADE2, ADE3, ADE4, ADE5, ADE6, ADE7, ADE8) (Scherens, et al., 2006). Since Gln3 and Gat1 are repressed by Ure2 (Cooper, 2002), we hypothesize that inactivation of Ure2 by the presence of [URE3] will upregulate these adenine biosynthesis genes, leading to an excess of the red AIR intermediate which accumulates in ade1 mutants resulting in darker red colonies. This effect depends on having the appropriate level of Ade1 protein which is apparently created by increased readthrough of ade1-14 caused by slight weakening of Sup35 activity by the GFP tagging and does not work in [psi−] cells with ade1-14 or ade2-1 mutations when SUP35 is wild-type ((Schwimmer and Masison, 2002) and unpublished).

Figure 3. Adenine biosynthesis pathway in yeast.

Adapted from (Rolfes, 2006).

We have described a convenient tool to analyze [URE3] in a strain that has been, and is still, widely used to study [PSI+]. Since a color assay is used to score for both the [PSI+] and [URE3] prions in this strain, large numbers of colonies can be easily scored for either the loss or gain of the prions. Thus this assay will facilitate the study of genetic and environmental effects on these two prions in the identical genetic background.

Acknowledgments

This work was supportedby National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM56350 to S.W.L. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility ofthe authors and do not necessarily represent the official viewsof NIH.

References

- Aigle M, Lacroute F. Genetical aspects of [URE3], a non-mitochondrial, cytoplasmically inherited mutation in yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;136:327–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00341717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann A, Toombs JA, Ross ED. Reporter assay systems for [URE3] detection and analysis. Methods. 2006;39:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JC, Lindquist S. A heritable switch in carbon source utilization driven by an unusual yeast prion. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2320–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.1839109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+] Science. 1995;268:880–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde J, Fink GR. A mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective for nuclear fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3651–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TG. Transmitting the signal of excess nitrogen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae from the Tor proteins to the GATA factors: connecting the dots. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:223–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Zhou P, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:507–19. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Chernoff YO, Kushnirov VV, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;144:1375–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Park KW, Yu H, Fan Q, Li L. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2008;40:460–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaglestone SS, Ruddock LW, Cox BS, Tuite MF. Guanidine hydrochloride blocks a critical step in the propagation of the prion-like determinant [PSI(+)] of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:240–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring ES, Grossman LI, Krupnick D, Cryer DR, Marmur J. The petite mutation in yeast. Loss of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid during induction of petites with ethidium bromide. J Mol Biol. 1970;52:323–35. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inge-Vechtomov SG, Tikhodeev ON, Karpova TS. Selective systems for obtaining recessive ribosomal suppressors in saccharomycete yeasts. Genetika. 1988;24:1159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama H, Edskes HK, Wickner RB. [URE3] prion propagation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: requirement for chaperone Hsp104 and curing by overexpressed chaperone Ydj1p. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8916–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8916-8922.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemecek J, Nakayashiki T, Wickner RB. A prion of yeast metacaspase homolog (Mca1p) detected by a genetic screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1892–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812470106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Patel BK, Gavin-Smyth J, Liebman SW. The yeast global transcriptional co-repressor protein Cyc8 can propagate as a prion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ncb1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoza T, Goginashvili A, Rodionova S, Ivanov M, Viktorovskaya O, Rubel A, Volkov K, Mironova L. Non-Mendelian determinant [ISP+] in yeast is a nuclear-residing prion form of the global transcriptional regulator Sfp1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10573–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfes RJ. Regulation of purine nucleotide biosynthesis: in yeast and beyond. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:786–90. doi: 10.1042/BST0340786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifitdinova AF, Nizhnikov AA, Lada AG, Rubel AA, Magomedova ZM, Ignatova VV, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Galkin AP. [NSI (+)]: a novel non-Mendelian nonsense suppressor determinant in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2010;56:467–78. doi: 10.1007/s00294-010-0314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute-Krishnan P, Serio TR. Prion protein remodelling confers an immediate phenotypic switch. Nature. 2005;437:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherens B, Feller A, Vierendeels F, Messenguy F, Dubois E. Identification of direct and indirect targets of the Gln3 and Gat1 activators by transcriptional profiling in response to nitrogen availability in the short and long term. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:777–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlumpberger M, Prusiner SB, Herskowitz I. Induction of distinct [URE3] yeast prion strains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7035–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7035-7046.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwimmer C, Masison DC. Antagonistic interactions between yeast [PSI(+)] and [URE3] prions and curing of [URE3] by Hsp70 protein chaperone Ssa1p but not by Ssa2p. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3590–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3590-3598.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Fink GR, Hicks JB. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Lab; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer N, Lindquist S. Rnq1: an epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:163–72. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB, Masison DC, Edskes HK. [PSI] and [URE3] as yeast prions. Yeast. 1995;11:1671–85. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB, Taylor KL, Edskes HK, Maddelein ML, Moriyama H, Roberts BT. Prions in Saccharomyces and Podospora spp.: protein-based inheritance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:844–61. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.844-861.1999. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]