Abstract

Purpose

A comprehensive multilevel intervention was tested to build organizational capacity to create and sustain improvement in quality of care and subsequently improve resident outcomes in nursing homes in need of improvement. Intervention facilities (n=29) received a two-year multilevel intervention with monthly on-site consultation from expert nurses with graduate education in gerontological nursing. Attention control facilities (n=29) that also needed to improve resident outcomes received monthly information about aging and physical assessment of elders.

Design and Methods

Randomized clinical trial of nursing homes in need of improving resident outcomes of bladder and bowel incontinence, weight loss, pressure ulcers, and decline in activities of daily living (ADL). It was hypothesized that following the intervention, experimental facilities would have better resident outcomes, higher quality of care, higher staff retention, more organizational attributes of improved working conditions than control facilities, similar staffing and staff mix, and lower total and direct care costs.

Results

The intervention did improve quality of care (p=0.02); there were improvements in pressure ulcers (p=0.05), weight loss (p=0.05). Staff retention, organizational working conditions, staffing, and staff mix and most costs were not affected by the intervention. Leadership turnover was surprisingly excessive in both intervention and control groups.

Implications

Some facilities that are in need of improving quality of care and resident outcomes are able to build the organizational capacity to improve while not increasing staffing or costs of care. Improvement requires continuous supportive consultation and leadership willing to involve staff and work together to build the systematic improvements in care delivery needed.

Keywords: randomized clinical trial, nursing homes, outcomes of care, cost analysis, quality improvement, staff retention, working conditions

Researchers have thus far conducted only limited and narrowly focused intervention studies to improve quality of care in nursing facilities. To date, none have tested and reported multi-level interventions that comprehensively address the quality of care in nursing homes. Existing narrowly focused studies informed this multilevel intervention designed to guide clinical practice changes that need to occur to improve care quality.

Clinical interventions that have been tested include those to reduce restraint use, promote exercise, manage or improve incontinence, improve depression, reduce social isolation, manage behavioral symptoms, reduce skin breakdown and reduce problems of weight loss. Also, some researchers have tested quality-improvement programs and ways of improving organizational leadership using an advanced practice nurse.

Some researchers have found it possible to reduce the use of physical restraints without serious injuries to residents.1–4 Others have shown that promoting exercise, strength training and ambulation can be effective for nursing home residents, even those who are frail and deconditioned.5–15 Residents, even those with dementia, can improve functional self-care abilities.16–19 Falls and serious injuries can be reduced,20–21 and risks of skin breakdown and pressure ulcers can be minimized.22–24

Many intervention studies have consistently demonstrated improvements in incontinence.25,7,26–31,12,32,14,33 In a quasi-experimental study of adults with severely impaired mobility, even the most impaired residents benefited from mechanical lifting devices and toileting prompts every two hours26; these study subjects also showed reduced incontinence, decubitus ulcers and urinary tract infections. Improvements in care delivery not only benefited residents but also resulted in lower care costs to the nursing home. However, some researchers have reported that it is difficult for nursing home staff to maintain toileting interventions after research staff leave27,34,14 and that proper follow-through with toileting care requires staff-management systems.25 Findings of these clinical studies were used prepare clinical materials and the basic care systems designed in the intervention to reinforce staff follow-through with care. Similarly, researchers have intervened successfully to improve residents' nutrition and hydration and minimize weight loss.35–40 It is important to note that the intervention procedures used in the majority of the clinical intervention studies were of short duration — hours, days, weeks or a few months. These short durations were appropriate for testing limited and narrow interventions. However, the duration for the multilevel intervention tested in this randomized study was two years to assure that managers and staff adopt and maintain improved care-delivery practices.

There have been limited numbers of more broadly designed intervention studies in nursing homes, such as those that revealed the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses.41–44 Only two studies in nursing homes have attempted all care systems quality-improvement interventions, and both demonstrated improvements in resident outcomes: mobility and constipation45 and falls, behavioral symptoms, little or no activity, and pressure ulcers.43 The first study45 used narrowly focused clinical conditions of hazardous mobility or constipation and nurse consultants to assist 30 experimental homes to learn quality-assurance methods and improve care. The intervention in the second study43 (three group design n=113) was more broadly focused on advanced practice nurse consultation and feedback reports of 23 quality indicators of clinical conditions, including incontinence, weight loss, dehydration, pressure ulcers, decline in ADL, behavior problems, depression and others.

Neither of these all care systems studies systematically addressed the critical issues of leadership, communication or commitment to group process for direct-care decision-making that are important features of the multilevel intervention tested in this study. A review of the effectiveness of organizational interventions for older persons concluded that “organizational interventions are potentially powerful methods to influence healthcare and maintain health status of older people”.46(p.416) The review also concluded that “changing systems of care requires major commitment and willingness to take risks by administrators and clinicians”.46(p.423)

The theoretical underpinnings of the multilevel intervention tested in this study are rooted in complexity theory, the emerging theory of organizations as complex adaptive systems (CAS). Complexity theory is characterized by interdependency and networks.47,48 Informal networks are key to the CAS, as agents interact with each other and the environment, get input and send outputs with some or all of the others in a network, and self-organize connections between people within and across the boundaries of a network.49 The intervention is based on the assumption that nursing facilities are CAS: The research nurse worked with facility staffs to increase the capacity of organizations to create sustained improvement by drawing staffs into interacting groups that are capable of self-organizing to implement different clinical practices to improve resident outcomes.

Complexity theory underpins the direction provided by the 2001 Institute of Medicine Report, Crossing the Quality Chasm.50 Several organizational studies in healthcare have approached organizations in this way. For example, researchers have studied complexity theory in hospitals,51,52 primary care practice,53–55 and nursing facilities.56,57 Organizations improve patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness when involving nurses, physicians and other healthcare professionals in decision-making.58–62 The intervention was designed so that the research nurse involved the staff, nurses and other healthcare professionals in decision-making as part of the intervention.

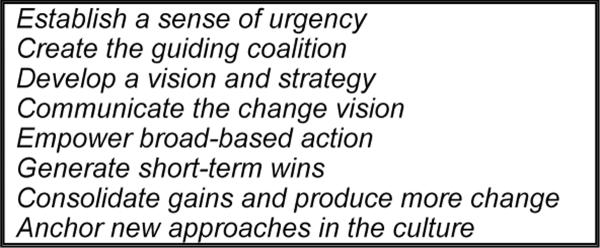

Guiding staff through change was critical to the intervention. Kotter's change model was suggested by other researchers63 as a practical guide for leading organizational change in long-term care.64 The model is based on his longitudinal research spanning more than two decades following the careers of executives in a variety of industries.65–70 Several studies have applied the model to organizational changes.71–73 The elements of Kotter's model guided the research nurse to work within the CAS of the nursing home to insure the key elements for sustaining change were addressed. Kotter's model provided direction to strategies as the nurse supported the development of teams, communication and feedback methods, and leadership.

The purpose of this randomized clinical trial was to test an experimental intervention focused on building organizational capacity to create and sustain improvement in quality of care and subsequently improve resident outcomes in nursing homes in need of improvement. Facilities in the intervention group (n=29) received a two-year experimental multilevel intervention that helped them (1) use quality-improvement methods, (2) use team and group processes to enhance direct-care decision-making, (3) focus on accomplishing the basics of care and (4) maintain more consistent nursing and administrative leadership committed to communication and active participation of staff in decision-making. Attention control facilities (n=29) that also needed to improve resident outcomes received monthly information about aging and physical assessment of elders.

Methods

A randomized, two-group, repeated-measures design was used to test the two-year multilevel intervention in nursing homes needing to improve quality of care and resident outcomes.

Sample

The population of nursing homes was limited to those in Missouri within a 103 county, three-hour driving radius of the project-coordinating site. This area encompassed two large urban cities, St. Louis and Kansas City, as well as rural and metropolitan areas. Qualified homes were those that needed to improve resident outcomes of care as measured by Minimum Data Set (MDS) Quality Indicator (QI) scores above the 40th percentile on at least three of four selected resident outcome measures for two consecutive six-month periods of MDS data. Because QIs are problem based scores, low scores are better, so requiring that facilities scored above the 40th percentile assured study homes had sufficient room for improvement to detect the effect of the intervention. Using two consecutive six-month periods of MDS data enhanced QI score stability for the selection process.74 The four QIs, bladder and bowel incontinence, weight loss, pressure ulcers and decline in ADL, are sufficiently prevalent in nursing homes, amenable to nursing intervention and sensitive to quality of care.74 Based on this analysis, 155 of the 356 certified skilled nursing homes within the 103 county driving radius were qualified for recruitment.

To avoid facilities from the same owner being assigned to both intervention and control groups, we first randomly assigned owners of facilities in the population of qualified facilities to either Control or Intervention groups. Then, we randomly contacted qualified facilities to participate, and, when they agreed, assigned them to the group designation based on owner. We continued random assignment until the groups were full. The enrollment was rolling, which allowed for oversampling as some homes dropped out due to changes in leadership/ownership after initially agreeing to participate. We oversampled to 38 intervention and 34 controls to assure we had a minimum of 29 to complete the 2 year intervention to achieve 80% power for outcome analysis. This plan was successful and 29 facilities in each group finished the study. Table 1 displays the remarkably similar facility demographics of the intervention and control groups. Acuity of the residents in the nursing homes in each group were not significantly different (p=0.51) at the beginning of the study using the RUG-III hierarchical classification method (www.interrai.org) that is commonly used in nursing homes. Nor were there group, time, or interaction effects at study end using analysis of variance. The statistical tests were corrected to accommodate the nested data structure of residents within homes using the method of generalized estimating equations.75

Intervention

The multilevel intervention was designed to build the systems of good care practices and leadership that foster organizational culture shown to enhance staff performance and improve resident outcomes. The multilevel intervention targeted three levels of staff responsible for operating a nursing facility: owners, nursing and administrative facility staff, and direct-care staff.

The multilevel intervention began with the research staff meeting with participating Intervention Group facility administrators and owners to explain the intervention and gain their cooperation. Project staff asked them to actively participate and support their facility staff as they embarked on the two-year study. Owners were asked, at least for the duration of the study, to (1) provide consistent nursing and administrative leadership, (2) adopt the elements of change (EC) into their management practices, and to actively support and encourage (3) the use of team and group processes for decision-making affecting resident care, (4) the use of a quality-improvement program and (5) the efforts of staff to focus on performing the basics of care, including ambulation, nutrition and hydration, toileting, bowel regularity, preventing skin breakdown and managing pain.

The theoretical foundation of the intervention was developed in formative research,76,77 as well in complexity theory and Kotter change theory discussed earlier in this article. The following is a scenario illustrating the intervention. Kotter's Elements of Change69 are noted in () throughout the scenario.

The research nurse observed direct-care staff at work and then met with them and nursing administrative staff in quality-improvement teams. These groups tailored care systems and practices outlined in the intervention manual to fit their situation, anchoring them into their facility's care routines. One scenario: A facility's residents were losing too much weight, as noted on their federal quality indicator facility report. The research nurse observed that there was little adaptive equipment to help residents eat independently, that most residents were fed in groups of 7 to 8 per staff member and that most residents were eating in their wheelchair. Within the quality improvement team, the research nurse pointed out the weight loss problem (establish a sense of urgency) then suggested that staff collect observational data using the tools in the intervention manual (create the guiding coalition). Data included the number of residents with weight loss, number using adaptive equipment, number being fed by staff and number eating in their wheelchair. The quality improvement team collected the suggested data, then met to discuss their observational data and made plans to correct the care practices they found. They prioritized their plans and decided to (1) focus on getting residents individualized adaptive equipment to encourage them to eat better and (2) identify residents who can sit in a dining chair, rather than wheelchair, for meals. The team worked with other staff to implement the changes (empower broad-based action) and then marked progress by making follow-up measurements of their observations (generate short-term wins). Once staff saw improvements coming from this system, their enthusiasm grew, and further changes became somewhat easier (consolidate gains and produce more change). During monthly site visits, the research nurse reinforced the direct-care staff to implement more changes, make follow-up measurements, and be sure the changes in practice were incorporated into facility care routines so they consistently happen as planned (anchor new approaches in the culture). The research nurse coached administrative staff by telephone and during monthly site visits to help them work with and through the teams (communicate the change vision). The research nurse urged the leaders to use a consistently reinforcing positive message in order to foster lasting changes in care practices that reduced weight loss (anchor new approaches in the culture).

A detailed Intervention Manual and two text books42,78 were provided to leadership of each intervention facility. (The Intervention Manual is available from the authors upon request.) Further detail of stakeholder participation, key intervention components, and the reinforcement processes for the multilevel intervention are in Appendix 1.

The attention control group received monthly videotaped in-services and reading materials about aging and physical assessment of elders, topics that were NOT directly related to quality-improvement strategies. These educational materials were designed to be of sufficient value to attention control facilities to retain them in the study. Contact with control facilities paralleled the intervention group. Educational materials were mailed monthly to each facility, and the co-principal investigator called each facility monthly to answer any questions about the materials. These monthly contacts avoided advising the use of quality-improvement strategies or the focus on the care basics required in the Intervention Group.

Hypotheses

Six hypotheses were proposed and tested.

Experimental (Intervention) facilities will have:

Higher quality of care than control facilities.

Better resident outcomes for bladder and bowel incontinence, weight loss, pressure ulcers and decline in ADL than control facilities.

Higher staff retention than control facilities.

More organizational attributes of improved working conditions than control facilities.

Staffing and staff mix that are similar to control facilities.

Lower total and direct-care costs than control facilities.

Analyses and Results

Quality of Care

The Observable Indicators of Nursing Home Care Quality (OIQ) is an instrument developed to measure quality of care following a brief 30 minute inspection of a nursing home.79–81 The OIQ has been field tested in 530 nursing homes in three states, undergone psychometric testing, and reduction to 30 reliable and discriminating items that are scored 1–5 with higher scores indicating better quality of care. It has seven first-order factors that group into two second-order factors of Structure and Process that are, in turn, the third-order factor of Quality of Care. Internal consistency is strong with Cronbach alpha's ranging from .74 –.93 for subscales; interrater and test-retest reliabilities are acceptable for the Process, Structure, and Total scales range from .64 –.76 and .75 –.77 respectively. The OIQ has strong evidence of construct validity with facility survey citations from federal inspections of the facilities for every subscale and total scale, some construct validity with quality indicators, and known groups' validity with citations.81 Scores are not normally distributed for this instrument, so nonparametric methods were used for analysis.

The OIQ was collected by an independent nurse observer at baseline and at the end of years one and two in the intervention group and baseline and end of year two in the control group as an overall measure of quality of care. The Wilcoxon Rank Test was used to make baseline comparisons of intervention and control groups with respect to each of the OIQ scales. There were no statistically significant differences at baseline.

Median change scores from baseline through study end were examined, revealing improved scores in the intervention group while control group OIQ scores worsened. For example, the intervention group improved 4.5 points on process subscales (possible point range 23–115) and 4 points on total score (possible point range 30–150); the control group scores declined -5 points on process subscales and -4 points on the total score.

Using Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, intervention and control groups were compared for group differences in OIQ change scores. Because there were twenty tests, p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the False Discovery Rate method.82 The care subscale was statistically significant (FDR p=0.022) as the intervention group had significantly better change scores than the control group (see Table 2). There are also raw p values of p=0.05 for the communication subscale and the process measures, reflecting the median change scores that also improved in the intervention group but not in the control group for those subscales.

Table 1.

Facility Demographics for Intervention and Control Groups

| Finished study | Bed range | Member of Chain | For profit | Not for profit | Gov | Metro | Urban | Rural | Baseline acuity RUGs III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 29 | 36–300 | 16 | 20 | 6 | 3 | 16 | 9 | 4 | 0.97 |

| Intervention | 29 | 52–246 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 5 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 0.98 |

Resident Outcomes

Four MDS QIs, bladder and bowel incontinence, weight loss, pressure ulcers and decline in ADL, were selected as the outcome measures for this study because these clinical problems are sufficiently prevalent in nursing homes, amenable to nursing intervention, and sensitive to quality of care.74 These four QIs also matched the clinical content of the basics of care component of the multilevel intervention (see Appendix 1), had been found to be valid and reliable measures of care quality in nursing homes,83–85,63,86 and were effective outcome measures in other intervention studies.43,87 Findings from validation studies revealed that the “QIs have a high degree of accuracy, or reliability. Average facility accuracy rates for the QIs ranged from 72% to 95%. The findings also reveal that the QIs have reasonably high predictive power at the higher threshold levels: If a facility was flagged at the 90th percentile, the probability that follow-up review found a problem with care was almost 70%, while the corresponding probability at the 95th percentile rose to 88%”.86(p.254) The four MDS QIs were calculated using standard algorithms88,89 for analysis. Additionally, the publically available MDS Quality Measures (QMs)90 that have similar algorithms applied to MDS data were analyzed.

QI scores were analyzed by quarter over the two year study duration for intervention and control facilities. Repeated measures analysis used logistic regression methods with the pre-intervention QI score as a covariate. The dependent variable was the QI score for each follow-up quarter. The independent variables were group membership, time (measured in quarters from enrollment), and a term for the group by time interaction. To adjust for facility variation in initial status the QI score for the first quarter following enrollment was used as a covariate. Repeated observations of the same facility result in correlated observations and so the method of generalized estimating equations75 was used to provide correct standard errors for the regression analysis. In these analyses, it was expected at some point that the intervention facilities would show a trend towards better QI scores while the control homes would remain flat. However, there were no statistically significant group by time interactions and only one main effect, pressure ulcers (p = 0.053). Table 3 displays the results of the repeated measures analysis. Plots were used to confirm the direction of any trends of outcomes. Only one outcome, pressure ulcers, showed improvement of 1.7 points in the intervention group while the control group remained the same. In the power analysis for the study, an improvement of 2.0 in pressure ulcer score was judged as clinically significant for facility improvement.

Table 2.

Significance Levels for Testing Group Differences in Observable Indicators of Quality (OIQ) Change Scores from Baseline through Study End

| Scale and Number of Items () | Possible Score Range | Raw p-value | FDR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Subscales | 0.050 | 0.172 | |

| Care (6) | 6–30 | 0.002 | 0.022 * |

| Communication (6) | 6–30 | 0.052 | 0.172 |

| Grooming (2) | 2–10 | 0.434 | 0.483 |

| Environment-Access (4) | 4–20 | 0.495 | 0.496 |

| Homelike (5) | 5–25 | 0.275 | 0.393 |

| Structure Subscales | 0.122 | 0.243 | |

| Environment-Basics (5) | 5–25 | 0.435 | 0.483 |

| Odor (1) | 2–10 | 0.086 | 0.215 |

| Total (30) | 30–150 | 0.173 | 0.289 |

The regression methods used for the analysis of QI data were also applied to the QM outcomes (incontinence, weight loss, late loss ADLs, bedfast, and pressure ulcers for high and low risk residents). There were no statistically significant interactions or main effects, except for a time effect (Qtr) for the weight loss QM (p = 0.048). Again, plots were used to confirm the direction of any trends. Only one outcome, weight loss, showed improvement of 3.4 points in the intervention group while the control group remained the same. In the power analysis for the study, an improvement of 2.0 in weight loss score was judged as clinically significant for facility improvement.

Staff Retention

Staff retention was measured using a method developed by Madsen (2005) for estimating staff turnover and calculating staff retention by using payroll date-of-hire and job-classification data that are readily accessible in nursing homes. The costs to organizations for staff turnover are extraordinary,42,92 with some estimates of more than 100% turnover of nursing assistants annually.93 It was anticipated that staff retention would improve in intervention facilities as compared to control as leaders learned to involve staff in decision-making and improvement teams as reinforced in the intervention that is detailed in Appendix 1.

The `turnover' statistic (TOR) (or retention statistic) was calculated for each home, each time period (baseline, end of year 1, end of year 2), each job category (nursing assistants, RN/LPN, Administrators/Others), and full-time or part-time. Because the estimates are better with larger sample sizes, at least 20 employees in a sub-group were required for analyses beyond description. That resulted in the combination of RN and LPN categories to RN/LPN as well as Administrators and Others due to small numbers of these staff. The TOR statistics for full-time and part-time were combined by taking a weighted average with the weights being related to the size of the sub-group.

Analysis of variance was done using the mixed model procedure in SAS v9.2; this procedure accounts for dependencies inherent in examining the same facilities over time. Anticipating an intervention effect at the end of year 1 and/or end of year 2, one would expect a group by time interaction effect. There was no evidence of a group effect. In both control and intervention groups, there was evidence of job category differences with the Administrators/Others category having lower (better) TOR means as compared to the RN/LPN or A/O categories (p<0.0010 in all cases). Table 4 displays descriptive statistics of number of years (or tenure) with the same facility for employees in this study by job category and full time or part time status, illustrating the better retention among the Administrator/Others category.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Results for QI Outcomes by Quarter for Study Duration

| QI | Parameter | Parameter Estimate | Significance | Odds Ratio | OR Lower 95% | OR Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder/Bowel Incontinence | IntvGrp | −0.044 | 0.476 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 1.08 |

| Qtr | −0.008 | 0.37 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.01 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | 0.005 | 0.75 | ||||

| qi8_0 | 0.036 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.04 | |

| Low Risk: Incontinence | IntvGrp | −0.051 | 0.44 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.08 |

| Qtr | 0.000 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.02 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | 0.008 | 0.63 | ||||

| qi8lr_0 | 0.036 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.04 | |

| High Risk: Incontinence | IntvGrp | −0.192 | 0.46 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 1.37 |

| Qtr | −0.034 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 1.10 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | 0.029 | 0.74 | ||||

| qi8hr_0 | 0.093 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.12 | |

| Weight Loss | IntvGrp | −0.113 | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.70 | 1.14 |

| Qtr | −0.028 | 0.16 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.01 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.028 | 0.40 | ||||

| qi14_0 | 0.023 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 | |

| Decline in Late Loss ADLs | IntvGrp | −0.039 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 1.24 |

| Qtr | −0.005 | 0.72 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.02 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.005 | 0.86 | ||||

| qi18_0 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | |

| Low Risk: Decline in ADL | IntvGrp | −0.015 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1.30 |

| Qtr | −0.003 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.03 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.006 | 0.86 | ||||

| qi18lr_0 | 0.014 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | |

| High Risk: Decline in ADL | IntvGrp | 0.024 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.76 | 1.39 |

| Qtr | −0.006 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.04 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | 0.009 | 0.80 | ||||

| qi18hr_0 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | |

| Stage 1–4 Pressure Ulcers | IntvGrp | 0.205 | 0.05* | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.51 |

| Qtr | 0.008 | 0.60 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.019 | 0.45 | ||||

| qi29_0 | 0.064 | 0.00 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.09 | |

| Low Risk: Pressure Ulcers | IntvGrp | 0.371 | 0.15 | 1.45 | 0.87 | 2.40 |

| Qtr | 0.014 | 0.79 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.13 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.080 | 0.29 | ||||

| qi29lr_0 | 0.050 | 0.06 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.11 | |

| High Risk: Pressure Ulcers | IntvGrp | 0.145 | 0.20 | 1.16 | 0.92 | 1.45 |

| Qtr | 0.002 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| IntvGrp*Qtr | −0.013 | 0.61 | ||||

| qi29hr_0 | 0.044 | 0.00 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

Leadership turnover can have a profound effect on the daily operations and care delivery in nursing homes.94,95 During recruitment of the participating facilities, owners and current leaders agreed to, if at all possible, keep leadership stable during the intervention study. Unfortunately, this was not the case. Table 5 displays the number of leaders in the Director of Nursing (DON) and Administrator positions that turned over during the two-year study duration. It also displays buyouts (ownership changes) of the nursing homes, something that occurred more than anticipated.

Table 4.

Number of Years with the Same Facility for Staff in Control and Intervention Groups

| Time | FT_PT | Position | Group | N | Mean | Median | Std Dev | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | FT | RN/LPN | C | 425 | 3.36 | 1.49 | 4.55 | 35.49 |

| Year 2 | C | 433 | 3.94 | 1.96 | 5.11 | 37.7 | ||

| Baseline | I | 401 | 4.03 | 1.65 | 5.50 | 29.07 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 452 | 4.21 | 2.18 | 5.46 | 30.74 | ||

| Baseline | A/O | C | 1047 | 3.23 | 1.19 | 5.07 | 38.99 | |

| Year 2 | C | 1253 | 3.34 | 1.26 | 5.05 | 40.96 | ||

| Baseline | I | 1261 | 3.79 | 1.35 | 5.61 | 32.17 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 1310 | 3.81 | 1.4 | 5.77 | 38.73 | ||

| Baseline | Admin/Other | C | 941 | 5.21 | 2.86 | 6.31 | 37.18 | |

| Year 2 | C | 923 | 5.64 | 3.14 | 6.82 | 46.67 | ||

| Baseline | I | 928 | 6.4 | 3.62 | 7.11 | 32.3 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 958 | 6.85 | 3.77 | 7.55 | 34.27 | ||

| Baseline | PT | RN/LPN | C | 161 | 3.06 | 1.47 | 3.85 | 17.72 |

| Year 2 | C | 164 | 3.16 | 1.38 | 4.05 | 21.58 | ||

| Baseline | I | 176 | 3.3 | 1.73 | 4.37 | 25.38 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 154 | 3.83 | 1.44 | 6.54 | 54.7 | ||

| Baseline | A/O | C | 333 | 2.37 | 1.03 | 3.79 | 29.05 | |

| Year 2 | C | 405 | 2.54 | 1.16 | 3.85 | 27.46 | ||

| Baseline | I | 384 | 2.16 | 0.84 | 3.97 | 31.84 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 432 | 2.59 | 1.16 | 3.94 | 31.04 | ||

| Baseline | Admin/Other | C | 281 | 2.72 | 1.04 | 4.22 | 27.71 | |

| Year 2 | C | 212 | 3.03 | 0.98 | 4.83 | 30.61 | ||

| Baseline | I | 326 | 3.19 | 1.33 | 4.84 | 26.35 | ||

| Year 2 | I | 396 | 3.44 | 1.42 | 5.32 | 41.13 |

There was higher administrator retention in the control facilities (24 controls had same administrator throughout the study, only 18 intervention facilities had the same administrator). Similarly, 16 control facilities had the same DON compared to only 7 intervention facilities with the same DON. There was extreme turnover of administrators in 2 intervention facilities (1 had 6 different administrators, another had 4 during the two year intervention); extreme turnover of DONs happened in 6 intervention facilities (1 had 7, 1 had 6, 3 had 5, and 2 had 4 different DONs during the two years). Control facilities had less administrative turnover; 1 facility had 4 different administrators; 1 had 7 DONs, 1 had 6, and 1 had 4 different DONs.

Summarizing, intervention facilities had 50% more turnover of DONs and 38% more administrator turnover than control facilities. Although control facilities had less administrative turnover, they had nearly twice the number of ownership changes than intervention facilities.

Organizational Working Conditions

The “Tell Us About Your Nursing Home” instrument is based on measuring communication, leadership, and teamwork using an adaptation of Shortell and colleagues' Organization and Management Survey.96,97 Earlier nursing home research suggested that it was the interplay of these organizational elements that created the culture and climate that influenced an organization's capacity to create and sustain improvement.98,99,96,97 The interplay was noted during observation and psychometric testing that reconstituted Shortell and colleagues' original subscales. The reconstituted subscales have been discussed in earlier publications and are labeled as connectedness (seven items), organizational harmony (ten items), clinical leadership (four items), and timely and understandable information (five items).100 It was anticipated that scores would reflect organizational attributes of improved working conditions in intervention facilities.

All staff were asked to complete the “Tell Us About Your Nursing Home” instrument at baseline and at the end of the study. A total of 7712 staff completed the instrument, 4150 at baseline and 3562 at the end of the study. The average return rate for intervention facilities was 71% at baseline and 63% at study end; for controls it was 65% and 53% respectively. Subscale and total scores for the facility are formed by averaging the staff scores (possible range 1–5 with higher scores meaning staff perception of improved working conditions) for the facility by staff group: RN/LPN, CNA, other, administrative, and job category not checked by the participant. Cronbach's alpha was calculated for each scale and the overall score using all complete survey responses from both pre and post intervention periods (n = 6,232). Surveys with some items missing were excluded. Alpha for the full scale is 0.961.

The actual score changes were small but consistently showed drifting of the means toward improving (higher) scores for both the intervention and control groups (Table 6). The findings presented in this table are very similar to findings from earlier studies.98,99 ANOVA methods were applied to each subscale to test for time and intervention effects. There were some significant time effects suggesting pre to post improvements within each group in areas of clinical leadership (p=.035), organizational harmony (p=.023), and timely information (p=.030) but no significant differences between the groups.

Table 5.

Leadership Turnover and Buyouts During Two Year Study Duration

| N | Total # DONs | Turnover DON % | Total # NHAs | Turnover NHA % | Same DON | Same NHA | Total # of Buyouts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 29 | 58 | 100% | 37 | 28% | 16 | 24 | 7 |

| Intervention | 29 | 72 | 150% | 48 | 66% | 7 | 18 | 4 |

An ad hoc analysis revealed a sub-group of about 7% of the staff in both the intervention and control groups who would not provide their job title on the survey. These surveys were classified as “job not given”. The summary statistics of the mean scores for each subscale and the total scale revealed that these employees consistently had the lowest scores. The pattern of highest (most favorable views of the organization) to the lowest were consistently: Administrative, RN/LPN, other, CNAs, then “not given”. Similarly, the length of employment had a pattern of consistent scores: highest (better) were new employees (under a year), then over 3 years, then 1–3 years, and lowest (poorer) were the “not given”. The years working with the elderly had the highest (better) scores for those less than a year, then 1–3 years, over 3 years, and “not given” were the lowest (poorer) scores.

Staffing and Staff Mix

Staff hours for RNs, LPNs and CNAs are a standard part of Medicaid cost reports. Staffing for each category of staff is expressed as hours per resident per day. It was hypothesized that staffing and staff mix would be similar in both intervention and control groups as the intervention focused on improving quality of care and overall involvement of staff in decision-making about care.

Because the distributions are right skewed, the median is the preferred measure of central tendency. As Table 7 displays, median RN staffing in the intervention facilities was slightly higher than in control. LPN staffing at baseline in the intervention facilities was lower than in control and increased to a similar staffing level by the end of the study. Median aide hours were consistently higher in intervention facilities than in control.

Table 6.

Staff Survey Results

| Group | Scale | Time | n | mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Total | Baseline | 1738 | 3.38 | 0.73 |

| C | Total | Year 2 | 1512 | 3.5 | 0.74 |

| C | Clinical Leadership | Baseline | 1754 | 3.21 | 0.94 |

| C | Clinical Leadership | Year 2 | 1535 | 3.38 | 0.95 |

| C | Cohesion | Baseline | 1766 | 3.78 | 0.75 |

| C | Cohesion | Year 2 | 1587 | 3.85 | 0.74 |

| C | Harmony | Baseline | 1747 | 3.29 | 0.77 |

| C | Harmony | Year 2 | 1519 | 3.43 | 0.78 |

| C | Timely Information | Baseline | 1769 | 3.15 | 0.83 |

| C | Timely Information | Year 2 | 1582 | 3.27 | 0.85 |

| I | Total | Baseline | 2310 | 3.39 | 0.71 |

| I | Total | Year 2 | 1891 | 3.44 | 0.75 |

| I | Clinical Leadership | Baseline | 2352 | 3.25 | 0.92 |

| I | Clinical Leadership | Year 2 | 1923 | 3.29 | 0.95 |

| I | Cohesion | Baseline | 2367 | 3.80 | 0.73 |

| I | Cohesion | Year 2 | 1947 | 3.80 | 0.75 |

| I | Harmony | Baseline | 2323 | 3.31 | 0.75 |

| I | Harmony | Year 2 | 1904 | 3.37 | 0.79 |

| I | Timely Information | Baseline | 2366 | 3.12 | 0.84 |

| I | Timely Information | Year 2 | 1946 | 3.21 | 0.88 |

The Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (a nonparametric analog of the two-sample t-test) was used to test for group differences with respect to change. The direction of the differencing is year 2 minus baseline. Significance levels were adjusted by the False Discovery Rate technique for multiple testing. As can be seen in Table 7, only one key variable, LPN hours per patient per day had significant within group changes during the study (p=.045) as intervention facilities had significant increases LPN hours. Tests for group differences, however, revealed no significant differences, although the LPN hours approached the level of significance.

Facility Costs

Total costs and direct resident care costs were calculated from the Medicaid cost reports provided by each facility to Missouri's Medicaid program. Also available from the cost reports were the total patient days for the reporting period. Because facility size and patient days are the primary determinants of costs, the outcomes for this hypothesis were expressed as costs per patient day. It was hypothesized that cost efficiencies would be gained while improving quality of care, involving staff in decision-making, improving staff retention and other benefits of improving organizational capacity. These cost efficiencies were likely to be detected in total costs, direct care costs, and staffing costs; however all cost categories reported in the cost reports were examined in detail.

Costs were analyzed in light of patient days, payer mix, staff hours per patient day, staff costs per patient day, median direct care and total costs with changes from baseline through study end. Total bed and patient days for the intervention group was slightly higher (32,414 baseline; 33, 012 study end) than the control (26,150 and 27,853); both groups experienced a small increase (2% and 7% respectively) during the study. At baseline, both groups served the Medicaid (61.5% intervention and 60.7% control) and Medicare (10% intervention and 8.6% control) populations, with similar percentages. Both increased the Medicare patients served during the study, with the control group increasing to 11.2%, near the level of the intervention (11.7%) at the end of the study.

Table 8 displays summary information for cost outcome variables for the intervention and control groups. Because the distributions are right skewed, the median is the preferred measure of central tendency. Total costs per patient per day increased 6% in the intervention group and reduced −3% in the control; total direct care costs increased in the intervention 9% but remained flat in the control. Total direct care costs as a percentage of total cost actually improved by 2% in both groups, indicating a trend in direct care cost efficiency in both. As previously stated, the baseline comparison of resident acuity was not significantly different nor were there group, time, or interaction effects.

Table 7.

Median Hours of Staffing per patient day and Significance Testing

| Outcome | Group | Baseline | Year 2 | Change | FDR p Within-Group | FDR p Between-Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN hours | C | 0.33 | 0.34 | 3% | .949 | |

| I | 0.35 | 0.37 | 5.7% | .362 | .225 | |

| LPN hours | C | 0.71 | 0.70 | −1.4% | .949 | |

| I | 0.59 | 0.69 | 17% | .045* | .060 | |

| Aide hours | C | 2.54 | 2.52 | −0.8% | .452 | |

| I | 2.67 | 2.70 | 1.1% | .970 | .200 |

The Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (a nonparametric analog of the two-sample t-test) was used to test for group differences with respect to change. The direction of the differencing is year 2 minus baseline. Significance levels were adjusted by the False Discovery Rate technique for multiple testing. As can be seen in Table 8, some key variables had significant within group changes in costs during the study. The intervention facilities had significant increases in total direct care costs, total costs, and total LPN costs. Control facilities had significant increases in percent direct care costs, total direct care costs, and total RN costs. Tests for group differences, however, revealed only one significant change in total LPN cost, as the intervention group experienced a 9% increase in LPN staffing costs. This is likely a reflection of the low LPN staffing level at baseline in the intervention facilities (0.59 hours per patient per day, as in Table 7) as compared to control (0.71); at study end the hours per patient day were nearly the same, 0.69 intervention and 0.70 control. This significant difference in LPN hours, understaffing in intervention facilities at the beginning of the study, may have affected the clinical outcomes measured.

Discussion

Helping nursing homes in need of improvement is essential as our country faces the largest surge in history of older adults in need of such care. Testing comprehensive organizational interventions such as the one in this randomized study is critical to most effectively guide the distribution of scarce resources that are allocated to improve nursing homes. We have learned in this study that it is possible to build the organizational capacity to create and sustain improvement in nursing homes in need of improving their overall quality of care (as measured by the OIQ) and in important clinical outcomes of pressure ulcers and weight loss. The intervention of monthly on-site consultations by nurses with graduate education in gerontological nursing is an effective method to help nursing homes improve clinical care and sustain it beyond limited interventions previously tested.10,29,43,101,14

While staffing and staff mix remained similar in the intervention and control groups, as was anticipated, so did staff retention, organizational working conditions, direct and total costs, these were anticipated to improve. Cost efficiencies were anticipated to result from the improvement in care quality. However, the comprehensive multilevel intervention was not sufficient to result in the anticipated organizational improvements in cost efficiencies, staff retention, or organizational working conditions. It is likely that for homes needing to improve quality of care, expecting them to be able to address not only quality of care but also the broader organizational improvements requires more intensive intervention. Administrative interventions such as intensive management education and coaching may be needed in combination with on-site monthly consultations focused on care improvement and team processes. Such a combination may require more frequent consultation or a combination of distance-mediated and on-site assistance to be a cost effective approach to improvement. One such combination has been pilot tested in a clinical intervention to improve incontinence and has demonstrated to be effective and low cost in facilitating improvement.102

There are some possible explanations for the lack of cost efficiency gains in the intervention facilities. During the two year intervention, despite recruitment procedures that included owners and administrators who agreed to keep leadership stable for the duration, there was 50% more DON turnover and 38% more administrator turnover in intervention facilities than control. With leadership turnover, business operations can falter, leading to uncertainty about “who will be the leader? And how will the new leader affect my job?” Uncertainty may cause employees within the organization to consider job changes that they might not normally consider; uncertainty may affect employee performance and may lead to increased operating costs. With increased leadership turnover in the intervention facilities, any potential cost efficiencies gained from the improvement in quality of care appears to have been washed away by increased turnover and resulting increased costs.

Other researchers have found similar increases in costs with leadership turnover.94 Also, direct care staff and administrator turnover is associated with a negative effect on quality of care.103 Similarly, turnover of less than 30% for RNs, 50% for LPNs, and 40% for CNAs could be targets to improve quality of care to residents.104 Staff retention, not turnover, for these categories of direct care staff were measured in our randomized study. Turnover of NHAs and DONs were calculated and revealed considerably higher rates in three of the four leadership groups in our randomized study (intervention group DON 150% and NHA 66%; control group DON 100% and NHA 28%, as in Table 5). It is likely that facilities in our randomized study were not attaining the low turnover targets recommended by Castle and colleagues for the clinical staff, since leadership turnover was so high. With leadership turnover and direct care staff turnover likely above these targets, costs efficiencies were not able to be attained.

From another cost perspective, ownership changes have been found to increase per patient day facility costs, but not result in increased spending for direct patient care.105 These results counter our cost findings of reduced total costs and no increase in direct care costs in control facilities that experienced nearly twice the ownership changes than the intervention facilities.

Importantly, improving quality of care does not have to cost more. This finding confirms other research with similar results.106,76–78 It is prudent to question the cost/benefit of enhancing quality or spending additional scarce resources to enhance quality of care. While it was anticipated that there would be cost savings with improved care processes and improved quality of care, based on our preliminary work,76,77 that was not the case for this randomized sample of nursing homes needing improvement. Prior studies addressed random samples of a complete population of nursing homes, including the full range of care quality as measured by their facility MDS quality indicators (excellent performance percentile scores through poor performance scores). It may be in the sample of nursing homes needing improvement, cost efficiencies gained from quality of care improvements are hidden within other organizational inefficiencies. Additional analyses are needed to discern these apparently complex relationships in homes needing improvement. To achieve the benefits of improved staff retention and cost efficiencies that have been measured as associated with quality improvement, perhaps a more targeted ownership and leadership intervention is needed. This would likely involve all staff in decision-making107,108 but be more leadership focused to assure follow through; however, it would also have to target improving leadership retention to be effective.

Better leadership retention likely has a positive impact on quality. Recently, a significant relationship was measured between leadership turnover and quality indicators of pain, pressure ulcers, and physical restraint use.109 The limited effect of improvement in quality indicators in this randomized study may have been adversely affected by the excessive leadership turnover experienced in the intervention facilities. Future research needs to focus on leadership retention strategies.

Shifting organizational working conditions, a closely linked concept to organizational culture, may be more difficult than was hypothesized, also an important finding. Both intervention and control facilities had remarkably stable perspectives within their facilities. While the measure used in this study has had widespread use and has measured a full range of quality of care,110,98,100,99 it has not been used in a longitudinal study to date to measure employee perspectives in changes in organizational working conditions. In a study designed to change the philosophy of care for nursing assistants from traditional care to restorative care,111 there are promising significant results in 12 nursing homes following a 12 month intervention with a research project RN on-site supporting the follow through of the intervention. In an 18 month coaching intervention in 9 nursing homes to promote culture change, some facilities made excellent progress, some moderate and others minimal.112 As other researchers have pointed out, further study about the effect of culture and interventions to promote it is clearly needed.113,114

This randomized control study has limitations to consider when interpreting results. The study was limited to one state within a three-hour, one-way driving radius. While the area included both rural and urban facilities, increasing generalizability, a multi-state study may have produced different results. The sample was from facilities in need of improving quality of care as measured by MDS quality indicators. (Recall 356 total facilities were within the driving radius and 155 were qualified as in need of improvement from which to sample). Although there is significant research using quality indicators for measurement of care quality, the data must be acknowledged as collected by facility staff and some government reports have recommended steps to improve accuracy.115 This was the first study in nursing homes to undertake a bundled multilevel intervention targeted to improving care delivery and cost outcomes. Not only did the research plan undertake a complex intervention, but it also attempted to apply it in a sample of nursing homes in need of improvement. The results of the study have to be interpreted for homes in need of improvement, not generalized to the full range of nursing homes that would include those providing better quality of care.

Helping facilities in need of improvement is a daunting task. Quality is multidimensional and the solutions to help facilities in need of improvement are also multidimensional. Where to start? Focus at the bedside to improve care processes? Focus on leadership to help them improve working conditions to retain staff? Focus on ownership to involve them in investing in leadership development, staff retention, cost efficiencies, care-delivery systems? A question that arose during our study was how hard to push leadership participating in the study to improve? Research staff struggle to maintain enrollment in the study to achieve sample size for managing effect measurement. Sometimes this makes study staff uncomfortable as they attempt to expand the participating leaders skills in group management or using the tools planned in the intervention. Study staff have questioned if their presence in some facilities actually sparked or enabled some leadership turnover. This could have been an unintended consequence of the intervention in homes needing improvement.

There are major policy implications from this study. Although some quality of care improvement occurred in the group of nursing homes needing improvement, should state and federal resources be devoted help to these facilities improve? Are there initial steps that should be taken first, such as stabilizing leadership then some intensive leadership coaching about staffing, care delivery, and business practices, before embarking on quality improvement initiatives? Should there be regulatory or reimbursement incentives for facilities with stable leadership? Should there be penalties for facilities or corporations with excessive leadership changes? What about stratifying quality improvement and regulatory approaches so that high performing facilities are expected to measurably perform and exceed the regulations and receive incentives for such performance? When nursing homes are consistently performing poorly, what remedial actions are needed and where should efforts begin to demand consistent improvement?

A comprehensive multilevel intervention was tested to build organizational capacity to create and sustain improvement in quality of care and subsequently improve resident outcomes in nursing homes in need of improvement. From the quantitative analysis of this randomized trial, we have learned that helping some facilities in need of improvement to actually improve care quality and improve some resident outcomes can be done effectively, while not increasing staffing and costs of care. While this was achieved many questions remain. Future research should focus on strategies for leadership skill improvement and retention in leadership positions; retention of nursing home staff, particularly direct care staff; involvement of direct care staff in decision-making about their work and care processes; and importantly, the needs and wants of the long term care consumers.

Figure 1.

Elements of Change (EC) (adapted from Kotter)

Table 8.

Median Facility Costs per Patient Day Median Values, Percent Change and Significance Testing

| Outcome | Group | Baseline | Year 2 | Relative % Change from Baseline | FDR p Within-Group | FDR p Between-Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Total direct care | C | 68.95% | 70.14% | 2% | .027* | |

| I | 71.75% | 73.14% | 2% | .388 | .380 | |

| Total direct care cost | C | $83.63 | $83.82 | 0% | .027* | |

| I | $82.06 | $89.32 | 9% | .000* | .090 | |

| Total costs | C | $123.10 | $119.66 | −3% | .155 | |

| I | $118.12 | $124.90 | 6% | .000* | .098 | |

| Total aide cost | C | $22.81 | $23.28 | 2% | .620 | |

| I | $24.95 | $26.18 | 5% | .148 | .380 | |

| Total LPN cost | C | $10.45 | $10.61 | 2% | .543 | |

| I | $10.32 | $11.23 | 9% | .001* | .050* | |

| Total RN cost | C | $7.29 | $7.80 | 7% | .048* | |

| I | $7.69 | $8.45 | 10% | .841 | .200 |

Acknowledgements

Evaluation activities were supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 5 R01 NR009040-05. Opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent NINR. The research team gratefully acknowledges the research nurses, De Minner and Margie Diekemper for their work and dedication to the nursing homes. We express our gratitude to Jessica Mueller for her amazing data base and project management skills. We also acknowledge the staff and leaders of the nursing home participants; they are truly committed to improving care delivery and quality of services to older people.

Appendix 1

Stakeholder Participation, Key Intervention Components, and Reinforcement Processes for the Intervention

| Stakeholders' Participation for the Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Models |

Owners | Nursing leaders and facility administrators |

Direct-care staff of the facilities |

Project staff |

| Key Components of the Intervention | ||||

|

Intervention

Model |

||||

|

Consistent

nursing and administrative leadership |

Agree to provide consistent nursing and administrative leadership; adopt the elements of change (EC) into their management practices |

Agree to actively provide consistent leadership; adopt EC into their management practices |

Reinforce with owners and staff that consistent leadership is essential as is continuous adaptive change |

|

|

Team/group

focus |

Actively support the use of team and group processes for decisions affecting resident care; actively use EC in management practices |

Actively use team and group processes for decisions affecting resident care; actively use EC in management practices |

Actively participate in team and group processes for decisions affecting resident care; actively use EC |

Teach use of team, group, and change processes to administrative and direct-care staff. Reinforce benefits of using team, group, and change process. |

|

Active quality-

improvement (QI) program |

Actively support the use of a quality- improvement program |

Actively use a quality- improvement program and involve direct-care staff in the QI activities |

Actively participate in the quality- improvement activities (problem identification, data collection, interpretation, and planned changes) |

Teach quality- improvement techniques. Assist with designing quality-improvement activities. Reinforce benefits of QI. Reinforce the use of change process |

|

Systems to

support the basics of care |

Actively support and encourage staff to focus on performing care basics (ambulation, nutrition and hydration, toileting and bowel regularity, preventing skin breakdown, and managing pain). |

Actively support and encourage direct-care staff to focus on performing care basics; reinforce the use of systems of care that promote performing care basics |

Adopt systems of care that help them focus on performing care basics and consistently use the systems of care to perform care basics |

Teach about the systems of care to perform care basics. Help the staff implement the systems of care. Reinforce use of systems of care to perform care basics. Reinforce use of change process and anchoring changes in systems of care |

| Reinforcement Processes for the Intervention | ||||

|

Elements of

Change (EC) Model |

||||

|

Establish a

sense of urgency Create the guiding coalition Develop a vision and strategy Communicate the change vision |

Actively support all staff to participate in educational program about QI, EC, and basics of care processes |

Participate in and actively support all staff to participate in baseline educational program about QI, EC, teams, and basics of care processes |

Participate in baseline educational program about QI, EC, teams, and basics of care processes |

Conduct baseline educational program about QI, EC, teams, and basics of care processes |

|

Create the

guiding coalition Communicate the change vision Empower broad- based action |

Actively support staff participation in the on-site monthly QI consultations; provide feedback on progress |

Actively support staff to participate in on- site monthly QI consultations tailored to each site and the projects they decide to do; use EC to support and encourage using team process |

Participate in on- site monthly QI consultations tailored to each site and the projects they decide to do, learn to use QI, team process and EC |

Provide on-site monthly QI consultations tailored to each site and the projects they decide to do; assist staff to learn team process for decision-making and how to use EC effectively; provide feedback on progress |

|

Generate short-

term wins Consolidate gains and produce more change Anchor new approaches in the culture |

Encourage staff to focus on the basics of care; provide feedback on progress |

Actively support staff to devote time to build the systems of care for getting the basics of care accomplished; use EC to support and encourage team process |

Implement the systems of care to support getting the basics of care accomplished |

Assist staff to learn how to implement systems of care to get the basics of care accomplished; provide feedback on progress |

|

Establish a

sense of urgency Develop a vision and strategy |

Participate in and encourage administrative staff to participate in monthly telephone support; provide feedback on progress |

Discuss progress regarding the quality- improvement program, use of group process and EC, and the focus on basics of care |

Make monthly telephone calls to owners and administrative staff to provide feedback about progress with QI, EC, and focus on the basics of care; provide feedback about baseline organizational measure (CVF) and how to use results; answer questions |

|

References

- 1.Evans LK, Strumpf NE, Allen-Taylor SL, Capezuti E, Maislin G, Jacobsen B. A clinical trial to reduce restraints in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:675–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld RR, Libow LS, Foley W, White H. Can physically restrained nursing-home residents be untied safely? Intervention and evaluation design. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(11):1264–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neufeld RR, Libow LS, Foley WJ, Dunbar JM, Cohen C, Breuer B. Restraint reduction reduces serious injuries among nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(10):1202–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner P, Koroknay V, Braum J, Cohen-Mansfield J. Individualized care alternatives used in the process of removing physical restraints in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:321–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiatarone MA, O'Neill EF, Doyle N, et al. The Boston FICSIT study: The effects of resistance training and nutritional supplementation on physical frailty in the oldest old. Journal of the Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(3):333–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagen B, Armstrong-Esther C, Sandilands M. On a happier note: validation of musical exercise for older persons in long-term care settings. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(4):347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jirovec MM. Effect of individualized prompted toileting on incontinence in nursing home residents. Appl Nurs Res. 1991;4(4):188–191. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(05)80096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koroknay VJ, Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Braun JV. Maintaining ambulation in the frail nursing home resident: A nursing administered walking program. J Gerontol Nurs. 1995;21(11):18–24. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19951101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacRae PG, Asplund LA, Schnelle JF, Ouslander JG, Abrahamse A, Morris C. A walking program for nursing home residents: effects on walk endurance, physical activity, mobility, and quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(2):175–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JN, Fiatarone M, Kiely DK, et al. Nursing rehabilitation and exercise strategies in the nursing home. J Geronotol: Med Sci. 1999;54A(10):M494–M500. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.10.m494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulrow CD, Gerety MB, Kanten D, et al. A randomized trial of physical rehabilitation for very frail nursing home residents. JAMA. 1994;271(7):519–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Ouslander JG, Simmons SF, Nitta M. Functional incidental training, mobility performance, and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(12):1356–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Giacobassi K, MacRae HSH, Simmons SF, Ouslander JG. Exercise with physically restrained nursing home residents: maximizing benefits of restraint reduction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(5):507–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, Al-Samarrai NR, Beck JC, Ouslander JG. Translating clinical research into practice: a randomized controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(9):1476–1483. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan JH. Tai Chi practice improves senior citizens' balance and arm movement control. J Aging Phys Activity. 1998;6(3):271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck C, Heacock P, Mercer SO, Walls RC, Rapp CG, Vogelpohl TS. Improving dressing behavior in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 1997;46(3):126–132. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199705000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blair CE. Combining behavior management an mutual goal setting to reduce physical dependency in nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 1995;44(3):160–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair CE. Effect of self-care ADLs on self-esteem on intact nursing home residents. Issues in Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20(6):559–570. doi: 10.1080/016128499248367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tappen RM. The effect of skill training on functional abilities of nursing home residents with dementia. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17(3):159–165. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron ID, Venman J, Kurrle SE, et al. Hip protectors in aged-care facilities: a randomized trial of use by individual higher-risk residents. Age Ageing. 2001;30(6):477–481. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.6.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray WA, Taylor JA, Meador KG, et al. A randomized trial of a consultation service to reduce falls in nursing homes. JAMA. 1997;278(7):557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geyer MJ, Brienza DM, Karg P, Trefler E, Kelsey S. A randomized control trial to evaluate pressure-reducing seat cushions for elderly wheelchair users. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(3):120–132. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groen HW, Groenier KH, Schuling J. Comparative study of a foam mattress and a water mattress. J Wound Care. 1999;8(7):333–335. doi: 10.12968/jowc.1999.8.7.25899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vyhlidal SK, Moxness D, Bosak KS, Van Meter FG, Bergstrom N. Mattress replacement or foam overlay? A prospective study on the incidence of pressure ulcers. Appl Nurs Res. 1997;10(3):111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(97)80193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgio LD, McCormick KA, Scheve AS, Engle BT, Hawkins A, Leahy E. The effects of changing prompted voiding schedules in the treatment of incontinence in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(3):315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormick KA, Cella M, Scheve A, Engel BT. Cost-effectiveness of treating incontinence in severely mobility-impaired long term care residents. Qual Rev Bull. 1990;12:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, et al. Predictors of successful prompted voiding among incontinent nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;273(17):1366–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouslander JG, Schnelle JF, Uman G, et al. Does oxybutynin add to the effectiveness of prompted voiding for urinary incontinence among nursing home residents? A placebo-controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(6):610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouslander JG, Al-Samarrai N, Schnelle JF. Prompted voiding for nighttime incontinence in nursing homes: is it effective? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(6):706–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer MH, Bennett RG, Marks J, McCormick KA, Engel BT. Urinary incontinence: A program that works. J Long Term Care Adm. 1994;22(2):19, 22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnelle JF, Keeler E, Hays RD, Simmons S, Ouslander JG, Siu AL. A cost and value analysis of two interventions with incontinent nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(10):1112–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnelle JF, Cruise PA, Alessi CA, Al-Samarrai N, Ouslander JG. Individualizing nighttime incontinence care in nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 1998;47(4):197–204. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnelle JF, Kapur K, Alessi C, et al. Does an exercise and incontinence intervention save healthcare costs in a nursing home population? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):161–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnelle JF, Newman D, White M, et al. Maintaining continence in nursing home residents through the application of industrial quality control. Gerontologist. 1993;33:114–121. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyne ML, Hoskins L. Improving eating behaviors in dementia using behavioral strategies. Clin Nurs Res. 1997;6(3):275–290. doi: 10.1177/105477389700600307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards NE, Beck AM. Animal-assisted therapy and nutrition in Alzheimer's disease. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24(6):697–712. doi: 10.1177/019394502320555430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauque S, Arnaud-Battandier F, Mansourian R, et al. Protein-energy oral supplementation in malnourished nursing-home residents. A controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2000;29(1):51–56. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmons SF, Alessi C, Schnelle JF. An intervention to increase fluid intake in nursing home residents: prompting and preference compliance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(7):926–933. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simmons SF, Osterweil D, Schnelle JF. Improving food intake in nursing home residents with feeding assistance: A staffing analysis. J Gerontol: Med Sci. 2001;56A(12):M790–M794. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.12.m790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simons D, Brailsford SR, Kidd EAM, Beighton D. The effect of medicated chewing gums on oral health in frail older people: A 1-year clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(8):1348–1353. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kane RL, Garrard J, Skay C, et al. Effects of a geriatric nurse practitioner on process and outcome of nursing home care. Am J Pub Health. 1989;79(9):1271–1277. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pillemer K. Solving the frontline crisis in long-term care: A practical guide to finding and keeping quality nursing assistants. Delmar Cengage Learning; New York (NY): 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rantz MJ, Popejoy L, Petroski GF, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a quality improvement intervention in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2001;41(4):525–538. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryden MB, Snyder M, Gross CR, et al. Value-added outcomes: The use of advanced practice nurses in long-term care facilities. Gerontologist. 2007;40(6):654–662. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.6.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohide EA, Tugwell P, Caulfield PA, et al. Randomized trial of quality assurance in nursing homes. Med Care. 1988;26(6):554–565. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reuben D. Organizational interventions to improve health outcomes of older persons. Med Care. 2002;40(5):416–428. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marion R. The Edge of Organization: Chaos and Complexity Theories of Formal Social Systems. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks (CA): 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. Edge ware: Insights from complexity science of health care leaders. VHA, Inc.; Irving (TX): 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stacey R. The science of complexity: an alternative perspective for strategic change processes. Strateg Manage J. 1995;16(6):477–495. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm. National Academy Press; Washington (DC): 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ashmos D, Duchon D, Hauge F, McDaniel R. Internal complexity and environmental sensitivity in hospitals. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1996;41(4):535–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ashmos D, Duchon D, McDaniel R. Physicians and decisions: a simple rule for increasing connections in hospitals. Health Care Management Review. 2000;25(1):109–115. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aita V, McIlvain H, Susman J, Crabtree B. Using metaphor as a qualitative analytic approach to understand complexity in primary care research. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(10):1419–1431. doi: 10.1177/1049732303255999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller W, Crabtree B, McDaniel R, Stange K. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller W, McDaniel R, Crabtree B, Stange K. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):872–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson R, Issel L, McDaniel R. Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems. Nurs Res. 2003;52(1):12–21. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson R, McDaniel R. The implication of environmental turbulence for nursing-unit design in effective nursing homes. Nurs Econ. 1992;10(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson R, McDaniel R. Intensity of registered nurse participation in nursing home decision making. Gerontologist. 1998;38(1):90–100. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anderson R, McDaniel R. RN participation in organizational decision making and improvements in resident outcomes. Health Care Manage Rev. 1999;24(1):7–16. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Issel L, Anderson R. Intensity of case managers' participation in organizational decision making. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(5):361–72. doi: 10.1002/nur.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashmos D, Huonker J, McDaniel R. Participation as a complicating mechanism: the effect of clinical professional and middle manager participation on hospital performance. Health Care Manage Rev. 1998;23(4):7–20. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199802340-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McDaniel R, Ashmos D. Internal stakeholder group participation in hospital strategic decision-making: making structure fit the moment. J Health Human Serv Admin. 1995;18(3):304–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morris JN, Moore T, Jones R, et al. Validation of long-term and post-acute care quality indicators. Executive summary of report to CMS, Contract # 500-95-0062/TO#2. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ronch J. Leading culture change in long-term care: A map for the road ahead. In: Weiner AS, Ronch JL, editors. Culture Change in Long-Term Care. The Haworth Social Work Practice Press; New York (NY): 2003. pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kotter J. What effective general managers really do. Harvard Bus Rev. 1982;77(2):145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kotter J. What leaders really do. Harvard Bus Rev. 1990;79(11):85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kotter JP. The New Rules: How to Succeed in Today's Post-Corporate World. The Free Press; New York (NY): 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kotter J. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Bus Rev. 1995;73(2):59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kotter JP. Leading Change. Harvard Business School Press; Boston (MA): 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kotter JP, Heskett JL. Corporate Culture and Performance. The Free Press; New York (NY): 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brodsky JA. Dealing with school closings as a change process: Buffalo and Jericho, 1976–1981 (New York) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1991;52(12 A):4157. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hughes E. A case study of an educational change effort at a multi-media company. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2003;64(2, A):377. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Speck E. Organizational change: A case study fo the Fairmont Chateau Whistler environmental sustainability program. Masters Abstracts International. 2002;42(2):560. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rantz MJ, Hicks L, Petroski GF, et al. Stability and sensitivity of nursing home quality indicators. J Gerontol: Med Sci. 2004;59A(1):79–82. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.m79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]