Abstract

Stromal cells have been studied extensively in the primary tumor microenvironment. In addition, mesenchymal stromal cells may participate in several steps of the metastatic cascade. Studying this interaction requires methods to distinguish and target stromal cells originating from the primary tumor versus their counterparts in the metastatic site. Here we illustrate a model of human tumor stromal cell—mouse cancer cell coimplantation. This model can be used to selectively deplete human stromal cells (using diphtheria toxin, DT) without affecting mouse cancer cells or host-derived stromal cells. Establishment of novel genetic models (e.g., transgenic expression of the DT receptor in specific cells) may eventually allow analogous models using syngeneic cells. Studying the role of stromal cells in metastasis using the model outlined above may take 8 weeks.

INTRODUCTION

Tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs) have important and diverse roles in carcinogenesis and tumor growth1–9. Although much less studied, primary TAF involvement is also potentially crucial when tumors colonize secondary sites during metastasis. Metastatic cells can reside in the lungs awaiting oncogenic activation10, or can home to pre-existing niches created by inflammation and immune cell or fibrocyte accumulation11–14. Alternatively, metastatic cells can proliferate intravascularly before extravasation into the lung tissue15. This could be a result of cancer cell clumping in circulation, a phenomenon that increases metastasis efficiency16–20. However, the clumps may also be fragments that carry over ‘passenger’ mesenchymal stromal cells from the primary site. By using the techniques described in this protocol, we have recently shown that mesenchymal stromal cells may serve as a provisional stroma in the secondary site and increase the metastatic efficiency of cancer21.

We developed an experimental protocol of spontaneous lung metastasis formation in mice in which human TAFs (originating from the primary tumor) can be selectively depleted using DT once they colonize the lungs. We have used this protocol—in combination with established spontaneous metastasis models using skin transplantation by transient parabiosis and an isolated tumor perfusion model22,23—to provide direct evidence for the role of passenger TAFs in tumor metastasis to the lungs (see ref. 21).

Overview of the technique

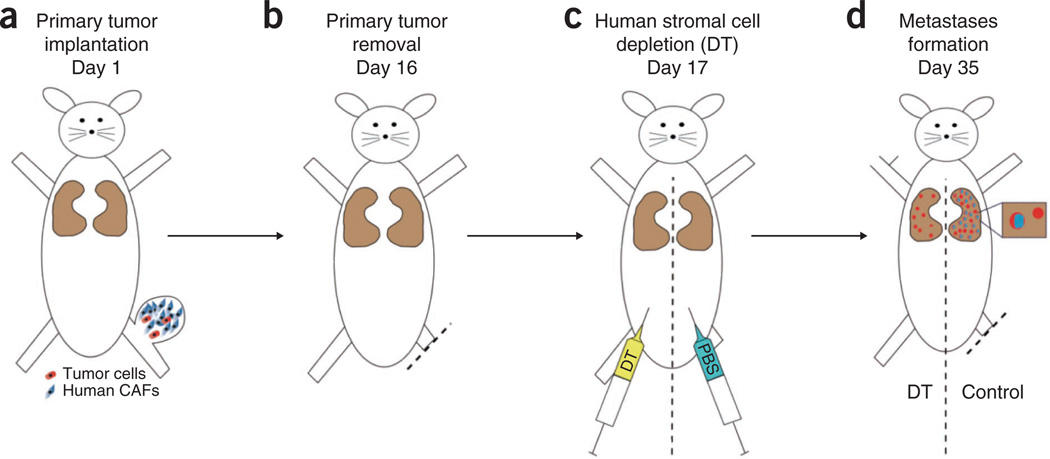

This protocol describes an experiment for studying the involvement of stromal cells in specific steps in the metastatic cascade. The experimental design of the protocol is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design of the experiment. (a–d) The use of human tumor (carcinoma)-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) enables selective depletion of stromal cells in a spontaneous metastasis model in mice with DT treatment using the following steps: primary tumor inoculation using metastatic mouse cancer cells (red) and human CAFs (blue) (a); primary tumor resection (b); depletion of human CAFs using diphtheria toxin 1 d after resection (c); and metastases formation in the lungs (d). All animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of public health service policy on humane care of laboratory animals and in accordance with an approved protocol by the institutional animal care and use committee of MGH.

We have previously used this protocol in a spontaneous metastasis formation model. We first isolated TAFs from fresh human breast cancer tissue, from independent cases of sporadic invasive ductal breast carcinomas (TNM stage II, SBR grade II–III). TAFs and tumor cells (LLC1) were implanted in the hind limb of a mouse and primary tumors were allowed to grow to a size of 10 mm before they were surgically resected. To determine the effect of passenger stromal cells within the circulating fragments, we selectively depleted the human TAFs using DT, which is 1,000 times more toxic to human cells compared with mouse cells24,25. The dosage of DT used in this protocol was effective in depleting human soft tissue sarcoma cells and TAFs, while having no adverse effect on mouse cell growth (i.e., normal or cancer cells)24,25. However, we recommend first determining an in vitro dose-response curve when using DT to deplete other types of human cells. Mice bearing LLC1 tumors were used as controls. Metastases were counted in the lungs 2 weeks later with a dissecting microscope and whole-mount lung tissue. Human passenger stromal cells were identified in metastatic nodules by immunohistochemistry using human-specific antibodies.

Comparison with other techniques

The hind limb model is a very reproducible postsurgical metastasis model without the risk of local tumor regrowth26–28. Tumor resection when grown in other sites (e.g., mammary pad) is technically feasible but is associated with high local relapse rates, which confounds the study outcomes. In addition, there are alternative models of fibroblast depletion that could be performed at specific time points during tumor progression. One example is the use of transgenic mice expressing the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) under the type I collagen promoter29. Another example is the use of transgenic mice that express HSV-TK under control of the S100A4 (FSP1) promoter to specifically ablate S100A4+ stromal cells8. Treatment with the antiviral agent ganciclovir can specifically induce apoptosis in cells expressing these markers. TAFs collected from these mice could potentially be used for coimplantation with tumor cells in a spontaneous model of metastasis.

Advantages and limitations

The key advantage of our protocol over other existing methods is that one can gain the ability to selectively deplete tumor stromal cells without affecting the microenvironment in the secondary site by coimplanting human-derived stromal cells with mouse tumor cells, followed by cell depletion using human-selective toxins. The limitation is the fact that the model uses xenotransplantation of a human tumor in an immunocompromised mouse. This limitation could be overcome by developing transgenic models, if feasible, of tumor stromal cell depletion using genetic tools in syngeneic and orthotopic tumor models.

Applications of the TAF model

In our experiments, we use TAFs isolated from human breast cancer tissue. By using the same technique, tissue-specific fibroblasts could be isolated from other organs such as prostate or liver (hepatic stellate cells)30,31

In our studies, we have focused on lung cancer and TAFs. However, in principle, the protocol could be used with any cancer line that is spontaneously metastatic to the lung in mouse experimental models, such as carcinomas (mammary, prostate, lung) and melanomas.

Tumor models bearing metastases in organs other than the lungs can be used to study organ-specific metastasis and microenvironment.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

PBS (1×; Cellgro, cat. no. 20-031-CV)

Antibodies: vimentin clone 3B4 (DAKO, cat. no. M7020), α-SMA (DAKO, cat. no. M0851), anti-pan-cytokeratin AE1-AE3 (Boehringer Mannheim) and CD31 (DAKO, cat. no. M0823)

Buprenorphine hydrochloride (0.3 mg ml −1; MGH pharmacy, cat. no. 716510)

Buprenorphine hydrochloride is a poison; it may cause prolonged respiratory depression. Wear protective clothing to avoid contact or inhalation. Buprenorphine is a controlled substance and should be handled according to relevant rules of the host institutions.

Buprenorphine hydrochloride is a poison; it may cause prolonged respiratory depression. Wear protective clothing to avoid contact or inhalation. Buprenorphine is a controlled substance and should be handled according to relevant rules of the host institutions.Calf serum (CS; Sigma, cat. no. C8056)

Collagenase type I (1 mg ml −1; Boehringer Mannheim)

Diphtheria toxin (DT) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae, lyophilized powder, 1 mg per vial (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. D0564)

DT is a pyrogen; do not inhale or expose it to the skin. Handle DT in a chemical hood while wearing appropriate protective clothing.

DT is a pyrogen; do not inhale or expose it to the skin. Handle DT in a chemical hood while wearing appropriate protective clothing.Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma, cat. no. D 5030)

Ethanol (70% (vol/vol); Pharmco, cat. no. 111000190)

Fatal-Plus (Vortech, cat. no. NDC 298-9373-68)

Fatal-Plus is a poisonous agent; caution should be exercised to avoid contact of the drug with open wounds or accidental self-inflicted injections.

Fatal-Plus is a poisonous agent; caution should be exercised to avoid contact of the drug with open wounds or accidental self-inflicted injections.Human fibroblasts isolated from human breast cancer tissue

Appropriate permissions must be obtained prior to using human breast tissue.

Appropriate permissions must be obtained prior to using human breast tissue.Human carcinoma–associated fibroblasts (isolated from human patients)

LLC1 cells (ATTC, cat. no. CRL-1642)

Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, 1×; Gibco, cat. no. 14170)

Hyaluronidase (125 units ml −1; Sigma)

Ketamine (100 mg ml −1; MGH pharmacy) and xylazine (10 mg ml −1; Webster, cat. no. 200204.00) mixture per kg body weight

Mice; immunodeficient mice (Nude/SCID) 6–10 weeks of age

All animal studies must be reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committees and conform to all relevant ethics regulations.

All animal studies must be reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committees and conform to all relevant ethics regulations.Paraformaldehyde (10% (wt/vol); Polyscience, cat. no. 4018)

Hazardous when exposed to skin, inhaled or swallowed. Preparation of 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde should be carried out in a chemical hood with appropriate clothing.

Hazardous when exposed to skin, inhaled or swallowed. Preparation of 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde should be carried out in a chemical hood with appropriate clothing.Sodium chloride

EQUIPMENT

Autoclip applier plus 9-mm autoclips (Roboz, cat. no. RS-9260 + RS-9262)

Bright-field microscope

Caliper (Roboz, cat. no. RS-6466)

Clipper (Webster, cat. no. 78997-010)

Cryomolds (Cardinal Health, cat. no. M7144-13)

Cryostat (Microm, cat. no. HM-560)

Fluorescence microscope (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation)

Heating pad (Shore Line, cat. no. 712.0000.04)

Hemostatic forceps, 9 inch, jaw length 6 cm (Roboz, cat. no. RS-7679)

MacLab (AD Instruments, cat. no. ML305)

Surgical blade no. 10 (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 08-916-5A), scalpel handle (Roboz, cat. no. RS-9843)

Syringe, 1 ml with 26-G needle for anesthesia (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 14-823-2E)

Incubator

REAGENT SETUP

Paraformaldehyde, 4% (wt/vol)

Prepare by adding 180 ml of 1× PBS to 120 ml of 10% (wt/vol) formaldehyde.  This solution has a short shelf-life (<1 week).

This solution has a short shelf-life (<1 week).

Diphtheria toxin

Reconstitute 1 mg of powder in the vial with 0.5 ml of 1× PBS to prepare stock solution (the solution will contain 1 mg of toxin in 10 mM Tris and 1 mM disodium EDTA at pH 7.5). To prepare 10 ml of final concentration (1 µg ml −1), add 5 µl of the stock solution to 200 ml of 1× PBS. Treat mice by one intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 0.2 ml of DT. Store at 4 °C for up to 4 weeks.

Buprenorphine hydrochloride

Dissolve 1 ml of the 0.3 mg ml −1 stock solution in 30 ml 0.9% (wt/vol) sodium chloride. Store at 20 °C for up to 3 months.

PBS (1×)

Add 100 ml of 10× PBS to 900 ml of dH2O. Store at room temperature (20 °C) for up to 9 months.

Ethanol, 70% (vol/vol)

Mix 1.7 liters of dH2O and 1 gallon of 100% ethanol. Store at 20 °C in a closed container.

PROCEDURE

Isolation of human TAFs from breast adenocarcinomas  3 months

3 months

-

1|

Isolate fibroblasts from cancer- and non-cancer–associated regions of breast tissues dissected from whole breast mastectomies as determined by gross examination at the time of surgical excision and subsequent histological analysis (see original method in ref. 6).

Appropriate permissions must be obtained prior to using breast tissue.

Appropriate permissions must be obtained prior to using breast tissue. Select minimally necrotic regions of the tumor mass.

Select minimally necrotic regions of the tumor mass. -

2|

Digest tissues using collagenase type I (1 mg ml −1) and hyaluronidase (125 U ml −1) at 37 °C with agitation for 12–18 h in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) CS.

-

3|

Incubate the dissociated tissues for 5 min at 20 °C without shaking.

-

4|

Transfer the stromal cell–enriched supernatant to a new tube (other tissues can be discarded).

-

5|

Centrifuge the stromal cell fraction at 250g for 5 min and resuspend the pellet (containing human TAF cells) in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) CS and transfer to 15-cm tissue culture plates.

-

6|

Expand TAFs by in vitro passage for two or three population doublings in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) CS in an incubator at 37 °C and in 5% CO2.

-

7|

Check the purity of these cell populations using immunocytochemistry with fluorescently labeled antibodies against human vimentin (clone 3B4), α-SMA, pan-cytokeratin AE1-AE3 and CD31. These should be performed according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Cells can be stored in liquid nitrogen indefinitely.

Cells can be stored in liquid nitrogen indefinitely.

Primary tumor implantation  1.5 h

1.5 h

-

8|

Use 8-week-old SCID mice. Anesthetize each mouse using 0.25 ml of ketamine/xylazine, place it on a heated pad, and then shave its right hind limb.

-

9|

Coimplant 2 × 105 LLC1 tumor cells and 1 × 106 TAFs (1:5 ratio) in 50 µl of HBSS in the right leg of the mouse using a 1-ml syringe with a 30-G needle. Insert the needle through the skin 1 mm distal to the knee joint on the lateral side. Create a 3-mm2 subcutaneous pocket by breaking through the muscle ligaments and moving the needle gently. Inject the cell mixture while retracting the needle. Tumors usually form in 100% of the mice.

TAFs should be used before the ninth in vitro passage, as they tend to grow slower (become senescent) afterward.

TAFs should be used before the ninth in vitro passage, as they tend to grow slower (become senescent) afterward. Avoid puncturing the skin while creating the pocket. This will cause the cell solution to leak out during injection.

Avoid puncturing the skin while creating the pocket. This will cause the cell solution to leak out during injection.

Primary tumor resection  30 min

30 min

-

10|

House the mice under standard pathogen-free conditions. Monitor the tumor growth daily and perform surgical resection as detailed below when tumors reach a mean diameter of 10 mm.

-

11|

Anesthetize the mouse using 0.4 ml of ketamine/xylazine mixture, and then place the mouse on a heated pad.

Dose the anesthesia carefully depending on the weight and strain of the mouse. For this procedure, deep anesthesia is required.

Dose the anesthesia carefully depending on the weight and strain of the mouse. For this procedure, deep anesthesia is required. -

12|

Five minutes after injection of the anesthetic, confirm that the mice are not responsive to pain stimuli (tail pinch, toe pinch).

-

13|

Shave the right inguinal region.

-

14|

Position a hemostatic clamp proximal to the tumor over the hip joint and close it tightly. Ensure that the site is clear of tumor tissue. At the same time, position the clamp as distal to the hip joint as possible to avoid clamping of the bladder and mouse genitals. The same clamping method could be use to resect tumors grown subcutaneously or in the mammary fat pad, but there is a higher risk of local regrowth of the tumors, which may confound the outcomes.

-

15|

Resect the hind limb distal to the clamp by using a surgical blade and holding the hemostatic clamp in the other hand.

Cut away from the hand in order to avoid injuries to the mouse and the researcher.

Cut away from the hand in order to avoid injuries to the mouse and the researcher. -

16|

Wait for 7 min to allow hemostasis while keeping the mouse on a heated pad.

-

17|

Release the hemostatic clamp and check the resection site for residual bleeding. When the wound is dry, close it with four 9-mm wound clips.

-

18|

Administer 0.2 ml of buprenorphine and ensure that the mice have easy access to food and water for 24 h postoperatively.

Selective depletion of human TA Fs with DT  15 min

15 min

-

19|

Prepare a 1-ml syringe with 0.2 ml of DT at a concentration of 1 µg ml −1 in PBS (use 0.2 ml of PBS for controls).

-

20|

Hold the mouse with the left thumb and index finger by the neck skin, stretch it over the left hand and hold the tail using the little finger on your left hand. With your right hand, inject the DT intraperitoneally in the lower right quadrant of the mouse’s abdomen. Move the needle to ensure that the DT is not injected in the internal organs. To confirm the selective killing of human tissue–derived TAFs, use two control groups: mice injected with mouse tumor cells alone, and mice injected with cancer cells and human TAFs and treated with inactive forms of DT (i.e., diphtheria toxoids).

Inject all solutions at room temperature to avoid a drop in body temperature after injection.

Inject all solutions at room temperature to avoid a drop in body temperature after injection.

Tissue collection and evaluation of metastatic tumor load in the lungs  30 min

30 min

-

21|

At the end point of the study (i.e., when metastases have formed in the target organ (e.g., 2 weeks after TAF depletion for LLC1 metastasis to the lungs)), euthanize the mice; use an i.p. injection of 0.2 ml of Fatal-Plus using a 1-ml syringe and a 26-G needle when the first mouse shows a body weight loss of more than 20%, signs of severe pain or distress (including ruffled hair, inability to self-ambulate and signs of dehydration), or when mice become moribund. Typically, the time point is approximately 14–21 d after primary tumor resection in this model.

-

22|

Open the thoracic cavity with forceps and scissors.

-

23|

Collect the lungs and separate the lobes. Metastasis formation in this model is observed in 90–100% of the mice. Count the metastatic nodules on the surface of each of the lobes using a dissecting microscope, as described elsewhere32. Microscopic evaluation of lung tissue section is recommended to complement the macroscopic metastasis evaluation.

![]()

Troubleshooting advice can be found in Table 1

Table 1.

Troubleshooting table.

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Difficulty in detaching fibroblasts from cell culture flask | Fibroblasts adhere to plastic too strongly | Increase the amount of trypsin/EDTA |

| 8 | Mouse is not fully anesthetized | Dose is insufficient | Different strains of mice may have disparate sensitivities to a particular anesthesia. The dose prescribed in the protocol generally provides a safe and appropriate response; however, this dose may not be sufficient in all situations |

| 9 | Tumor does not grow | Tumor cells are not viable | Repeat in vitro cell culture and counting. Keep the cells on ice during all procedures prior to implantation |

| 10 | Difficulty closing the hemostatic clamp | Clamp is too small for the size of the mouse | Use appropriate hemostatic clamps as described in the MATERIALS section |

| 14 | Wound bleeding after removal of the clamp | Incomplete closure of the clamp or too early removal | Re-apply the clamp and wait for another 5 min before proceeding to the next step |

| 23 | Inability to count metastatic nodules | Nodules are too numerous to count | Some tumor cell lines are extremely metastatic. Resect primary tumors at an earlier stage. However, a minimum size of 8 mm may be required for tumor metastases |

| Nodules are difficult to detect | The metastatic nodules are usually clearly visible on the lung’s surface without staining. However, to improve the visibility of nodules, lungs could be fixed in Bouin’s fixative diluted 1:5 with neutral-buffered formalin. In addition, microscopic evaluation could be used to further quantify metastatic burden |

![]()

Selective depletion of human TA Fs in mice

Steps 1–7, isolation of TAFs from human breast adenocarcinoma tissue: 3 months

Steps 8 and 9, coimplantation of TAFs and cancer cells in the hind limb of an immunodeficient mouse: 1.5 h

Steps 10–18, complete resection of the primary tumor by hind limb amputation: 30 min

Steps 19 and 20, selective depletion of human TAFs using an i.p. injection of DT: 15 min

Steps 21–23, collection of the lungs and evaluation of the metastatic burden: 30 min

ANTICIPATE D RESULTS

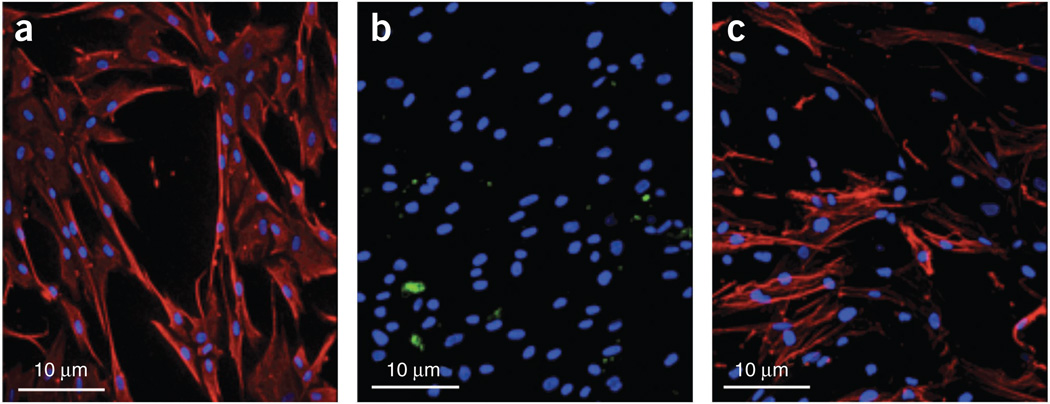

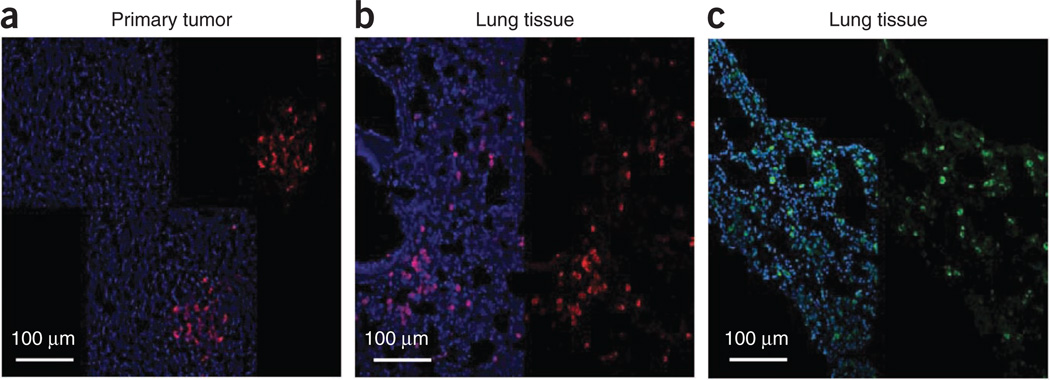

Typical results of the isolation of TAFs from human tissues are shown in Figure 2. Isolated cell lines were stained with vimentin to show their mesenchymal lineage (human breast cancer cells were used as a control). We confirmed this finding using immunocytochemical staining with pan-cytokeratin–specific AE1–AE3 antibodies to rule out epithelial cell contamination. Next, we confirmed that the TAFs are ‘activated’ myofibroblasts, in contrast to ‘resting’ skin fibroblasts and normal fibroblasts, isolated from breast tissue > 2 cm away from the tumor, which express lower levels of α-SMA. Finally, we used CD31 to rule out endothelial lineage of the isolated TAFs and normal fibroblasts. Human stromal cells could be coimplanted with tumor cells and be selectively depleted at a chosen time point. By immunostaining with anti-human vimentin antibody, which is specific for human cells—i.e., it does not stain mouse cells or tumor cells in this model—we showed incorporation of human TAFs in the primary tumor as well as their presence in the metastatic site21 (Fig. 3a,b). The presence of human passenger TAFs in the lungs was confirmed by immunostaining for human nuclear antigen21 (Fig. 3c).

Figure 2.

Isolation of tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs) from breast cancer specimens. (a–c) Representative images of immunocytochemical staining for human vimentin (a), cytokeratin AE1-AE3 (b) and α-SMA (c), showing characteristic mesenchymal phenotype. Blue, DAPI nuclear stain (in a–c). Red, vimentin (in a) and α-SMA (in c). Images are 315 µm across.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous metastasis of the passenger stromal cells in the coimplantation model. (a–c) Human CAFs coimplanted in the primary tumor site (a) and metastasizing to the lung (b,c). Immunohistochemical markers have been used to identify human cells using Cy3-labeled antihuman vimentin antibody (a,b) and FITC-labeled antihuman nuclear antigen antibody (c). Images are 700 µm across. Reproduced with permission from ref. 21. All animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of public health service policy on humane care of laboratory animals, and in accordance with an approved protocol by the institutional animal care and use committee of MGH.

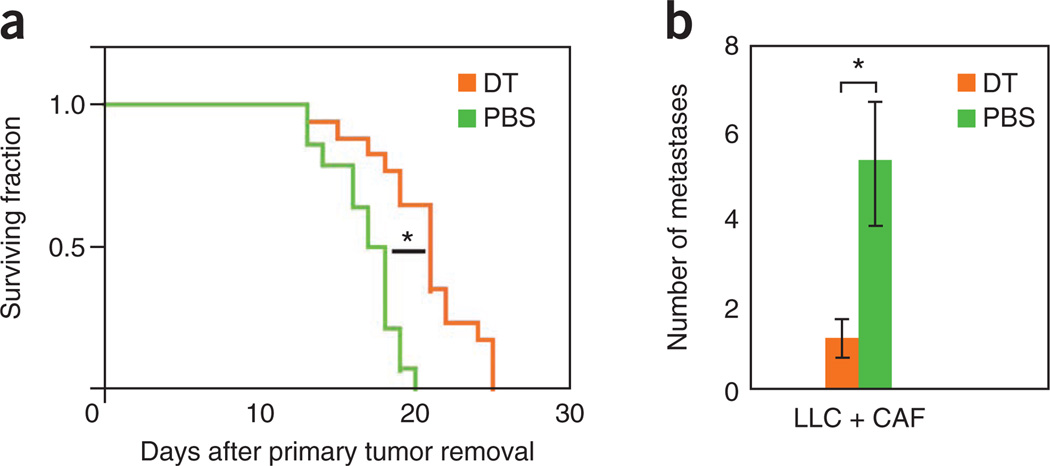

Furthermore, Figure 3 shows the results of TAF depletion during the metastatic process. When using the timelines as described above, the primary tumor is allowed to grow to a size that facilitates metastases formation. (No resection of the primary tumor or resection of tumors at a smaller size does not usually induce metastasis formation in this tumor model.) When the circulating stromal cells, as well as the stromal cells in the micrometastases, are depleted (after primary tumor removal) using DT, the outgrowth of micrometastases in the lung decreases significantly (Fig. 4a). Moreover, TAF depletion results in increased survival (Fig. 4b). Together, this indicates that the presence of stromal cells in circulating tumor fragments increases their viability and promotes metastatic seeding21.

Figure 4.

Contribution of circulating stromal cells to spontaneous tumor metastases. (a,b) Selective depletion of stromal cells in the circulating fragments using DT results in prolonged survival (survival experiment in a) and a decrease in the number of lung metastases (time-matched evaluation in b). *P < 0.05. Reproduced with permission from ref. 21. All animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of public health service policy on humane care of laboratory animals and in accordance with an approved protocol by the institutional animal care and use committee of MGH.

Acknowledgments

The work of the authors is supported by US National Cancer Institute grants P01-CA80124, R01-CA115767, R01-CA85140, R01-CA126642 and T32-CA73479 (R.K.J.), R01-CA96915 (D.F.), R21-CA139168 and R01-CA159258 (D.G.D.) and Federal Share Proton Beam Program grants (R.K.J., D.F. and D.G.D.); Department of Defense Innovator Award W81XWH-10-1-0016 (R.K.J.) and Predoctoral Fellowship W81XWH-06-1-0781 (A.M.M.J.D.); American Cancer Society grant RSG-11-073-01TBG (D.G.D.); and Stichting Michael Van Vloten Fonds and the Stichting Jo Kolk (A.M.M.J.D.). We acknowledge the outstanding technical assistance of J. Kahn, S. Roberge and P. Huang with animal models.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS D.G.D., D.F. and R.K.J. designed the studies; A.M.M.J.D. and E.J.A.S. performed the experiments; D.G.D., D.F., A.M.M.J.D. and R.K.J. analyzed the data; and A.M.M.J.D., R.K.J. and D.G.D. edited the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bhowmick NA, et al. TGF-β signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs TW, Byrne C, Colditz G, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ. Radial scars in benign breast-biopsy specimens and the risk of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:430–436. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elenbaas B, et al. Human breast cancer cells generated by oncogenic transformation of primary mammary epithelial cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:50–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.828901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olumi AF, et al. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orimo A, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tlsty TD. Stromal cells can contribute oncogenic signals. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2001;11:97–104. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connell JT, et al. VEGF-A and Tenascin-C produced by S100A4+ stromal cells are important for metastatic colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16002–16007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podsypanina K, et al. Seeding and propagation of untransformed mouse mammary cells in the lung. Science. 2008;321:1841–1844. doi: 10.1126/science.1161621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiratsuka S, et al. MMP9 induction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 is involved in lung-specific metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:289–300. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan RN, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S, et al. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deventer K, Pozo OJ, Van Eenoo P, Delbeke FT. Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of ephedrines in urine. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009;877:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Mehdi AB, et al. Intravascular origin of metastasis from the proliferation of endothelium-attached tumor cells: a new model for metastasis. Nat. Med. 2000;6:100–102. doi: 10.1038/71429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liotta LA, Saidel MG, Kleinerman J. The significance of hematogenous tumor cell clumps in the metastatic process. Cancer Res. 1976;36:889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fidler IJ. The relationship of embolic homogeneity, number, size and viability to the incidence of experimental metastasis. Eur. J. Cancer. 1973;9:223–227. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2964(73)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiter DJ, van Krieken JH, van Muijen GN, deWaal RM. Tumour metastasis: is tissue an issue? Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:109–112. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahai E. Illuminating the metastatic process. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:737–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duda DG, et al. Malignant cells facilitate lung metastasis by bringing their own soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21677–21682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016234107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duyverman AMMJ, Kohno M, Duda DG, Jain RK, Fukumura D. A transient parabiosis skin transplantation model in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:763–770. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duyverman AMMJ, et al. An isolated tumor perfusion model in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:749–755. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbiser JL, et al. Isolation of mouse stromal cells associated with a human tumor using differential diphtheria toxin sensitivity. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:723–729. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Padera TP, et al. Pathology: cancer cells compress intratumour vessels. Nature. 2004;427:695. doi: 10.1038/427695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padera TP, et al. Lymphatic metastasis in the absence of functional intratumor lymphatics. Science. 2002;296:1883–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1071420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson MR, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. VEGFR1-activity-independent metastasis formation. Nature. 2009;461:E4–E5. doi: 10.1038/nature08254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiratsuka S, et al. C-X-C receptor type 4 promotes metastasis by activating p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in myeloid differentiation antigen (Gr-1)-positive cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:302–307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016917108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian B, Han L, Kleidon J, Henke C. An HSV-TK transgenic mouse model to evaluate elimination of fibroblasts for fibrosis therapy. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163:789–801. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63706-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kassen A, et al. Stromal cells of the human prostate: initial isolation and characterization. Prostate. 1996;28:89–97. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199602)28:2<89::AID-PROS3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzocca A, et al. Tumor-secreted lysophostatidic acid accelerates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by promoting differentiation of peritumoral fibroblasts in myofibroblasts. Hepatology. 2011;54:920–930. doi: 10.1002/hep.24485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch DR. Technical considerations for studying cancer metastasisin vivo . Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1997;15:272–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1018477516367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]