Abstract

Aim of the study

Sudden cardiac arrest (CA) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Previously we demonstrated that administration of sodium sulfide (Na2S), a hydrogen sulfide (H2S) donor, markedly improved the neurological outcome and survival rate at 24h after CA and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in mice. In this study, we sought to elucidate the mechanism responsible for the neuroprotective effects of Na2S and its impact on the long-term survival after CA/CPR in mice.

Methods

Adult male mice were subjected to potassium-induced CA for 7.5 min at 37°C whereupon CPR was performed with chest compression and mechanical ventilation. Mice received Na2S (0.55 mg/kg i.v.) or vehicle 1 min before CPR.

Results

Mice that were subjected to CA/CPR and received vehicle exhibited a poor 10-day survival rate (4/12) and depressed neurological function. Cardiac arrest and CPR induced abnormal water diffusion in the vulnerable regions of the brain, as demonstrated by hyperintense diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) 24h after CA/CPR. Extent of hyperintense DWI was associated with matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) activation, worse neurological outcomes, and poor survival rate at 10 days after CA/CPR. Administration of Na2S prevented the development of abnormal water diffusion and MMP-9 activation and markedly improved neurological function and long-term survival (9/12, P<0.05 vs. vehicle) after CA/CPR.

Conclusion

These results suggest that administration of Na2S 1 min before CPR improves neurological function and survival rate at 10 days after CA/CPR by preventing water diffusion abnormality in the brain potentially via inhibiting MMP-9 activation early after resuscitation.

Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest (CA) is a leading cause of death worldwide.1 Despite advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) methods,2,3 about 10% of adult out-of-hospital CA victims survive to hospital discharge,4 and up to 60% of survivors have moderate to severe cognitive deficits 3 months after resuscitation.5 To date, no pharmacological agent is available to improve outcome from post-CA syndrome.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a colorless gas with a characteristic rotten-egg odor.6,7 It has been reported that administration of an H2S donor (Na2S) attenuates myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion (IR) injury in rodents8 and pigs.9 Along these lines, we have recently reported that administration of Na2S 1 min before CPR markedly improved neurological outcome and survival 24h after CA/CPR in mice.10 Beneficial effects of Na2S were associated with inhibition of caspase-3 activation and neuronal death. While these observations suggest that Na2S exert neuroprotection after CA/CPR, mechanisms responsible for the neuroprotective effects of Na2S and whether or not Na2S improves long-term survival after CA/CPR remain to be determined.

The primary goal of this study was to examine the mechanisms responsible for the neuroprotective effects of Na2S after CA/CPR. We hypothesized that Na2S protects brain after CA/CPR by preventing brain edema by mitigating the disruption of blood brain barrier (BBB). To address this hypothesis, we assessed abnormality in water diffusion in the brain caused by BBB leakage by DWI in live mice. Here, we report that administration of Na2S at the initiation of CPR improves neurological function and 10-day survival after CA/CPR by mitigating the BBB disruption via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) activation.

Methods

Animals and Materials

After approval by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, we studied 2- to 3-month-old age and weight-matched male C57BL/6J wild-type mice. Sodium sulfide (Na2S; IK1001) was a generous gift from Ikaria Inc. (Seattle, WA, USA).

Animal preparation

Mice were anaesthetized with 100 μg/g of ketamine and 0.25 μg/g fentanyl delivered by intraperitoneal injection and mechanically ventilated (FiO2=0.21, mini-vent, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). Arterial blood pressure was measured via left femoral arterial line. A saline-filled microcatheter (PE-10, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was inserted into the left femoral vein for drug and fluid administration. Blood pressure and needle-probe ECG monitoring data were recorded and analyzed with the use of a PC-based data acquisition system.

Murine CPR model

CA and CPR in mice were performed as previously described.10,11 Briefly, after instrumentation under anaesthesia, CA was induced by administration of 0.08 mg/g potassium chloride (KCl) through the femoral catheter and was confirmed by loss of arterial pressure and asystolic rhythm on ECG. Although the induction of CA by bolus administration of KCl may have limited clinical relevance, we believe that this model provides a valuable platform for elucidating the mechanisms of post-CA brain injury and defining the effects of therapeutic strategies on long-term outcomes after CA/CPR. Instead of the 8 min arrest time as we used in the previous study,10 we used a 7.5 min arrest time in this investigation to enable longer survival of mice after CA/CPR. After 7.5 min of CA, chest compressions were delivered using a finger at a rate of 340 to 360beats per minute with resumption of mechanical ventilation (FiO2=1.0) (Supplemental Figure 1 in the online-only supplementary data). Epinephrine was infused at 0.3 μg/min starting 30 seconds before CPR and continued until heart rate (HR) became higher than 300 bpm. Total dose of epinephrine used in this study was within the range of recommended dose in Advanced Cardiac Life Support guideline (Supplemental Table 1 in the online-only supplementary data).12 Core body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a warming lamp for the first hour after CPR. Mice were weaned from mechanical ventilation and extubated at 1h after CPR. Study drug (Na2S) or vehicle was injected via the femoral venous line 1 min before CPR. Based on the previous studies, we administered 0.55 mg/kg (7.0 μmol/kg) of Na2S.

Assessment of neurological function

Neurological function was assessed at 24 and 96h after CA/CPR using a previously-reported neurological function scoring system with minor modifications.10,11,13

Acquisition and analysis of MRI

To investigate the degree of ischaemic brain injury after CA, DWI was performed in mice treated with vehicle (n=7) or Na2S (n=8) 24h after CPR. During magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane administered through a nose cone. Imaging employed a conventional multi-shot spin-echo sequence with an isotropic resolution of 230 μm in the image plane and ten 1 mm slices to nearly cover whole brain using a repetition time of 1500 ms and an echo time of 20 ms. Two diffusion-sensitizing gradients (154 and 1294 sec/mm2) were applied in the slice direction, and eight DWI pairs were acquired over 25 min. To minimize image artifacts due to respiration, repeated MRI acquisitions were averaged using a weighting function equal to the inverse of the global variance with respect to the mean. Time-averaged images were registered to the coordinate space of the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas14 by automated 12-parameter affine alignment followed by adjustment of three-dimensional distortion fields using publicly available software distributed by the Neuroimaging Informatics Tools and Resources Clearinghouse (NITRC). Maps of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC in units of μm2/ms) were computed for each animal in the standardized space. Bilaterally symmetric regions of interest were defined based upon subject-averaged ADC maps and anatomical delineations from the mouse brain atlas. ADC values were computed in each mouse across each region of interest (ROI) and group average ADC of mice treated with vehicle or Na2S were reported for each ROI.

Gelatin zymography

MMP-9 activity in the brain was assessed with gelatin zymography according to the method described previously.15 Data were quantified with image densitometry.

In vivo hybridization of cerebral MMP-9 mRNA expression after CA/CPR

To determine the spatial correlation between brain regions with abnormal water diffusion exhibited by hyperintense DWI and brain damage as determined by MMP-9 mRNA expression, FITC-labeled antisense phosphorothioate-modified oligodeoxynucleotide (sODN)-MMP-9 (120 pmol/kg, i.p) was delivered immediately after brain MRI at 24h after CA/CPR in subgroups of mice that were treated with Na2S or vehicle (n=3 in each group). Sequence and synthesis of the FITC-sODN-MMP-9 has been reported elsewhere.16 Mice were euthanized 12h after FITC-sODN-MMP-9 injection, retrogradely perfused with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and the brain was removed and incubated in 4% PFA followed by 10-30% sucrose at 4°C. Brain tissue section of 20 μm thickness were dissected with cryostat and stored at -80°C. Cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst. Cells expressing MMP-9 mRNA were detected as FITC-positive cells, as previously described.16

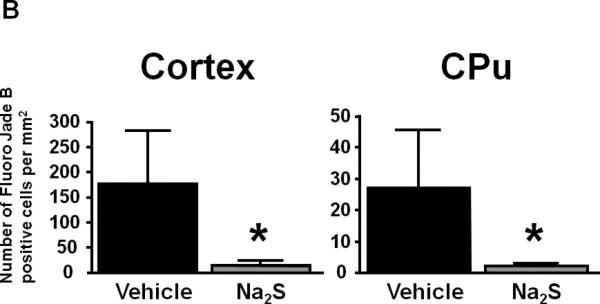

Detection of neuronal degeneration

Neuronal degeneration in the brain was assessed with Fluoro-Jade B staining according to the method described previously.17 Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in cortex and caudoputamen (CPu) were counted by an investigator blinded to the treatment group, and the number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells per 1 mm2 in examined area was reported.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean±SEM. Normally distributed data were analyzed using unpaired t-test, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, or one-way ANOVA with a Holm-Sidak or Bonferroni post hoc test. Difference in survival rate was analyzed by Gehan-Breslow test. Numbers of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test because the values are not normally distributed. Sigmastat 3.01a (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) were used for statistical analyses.

Results

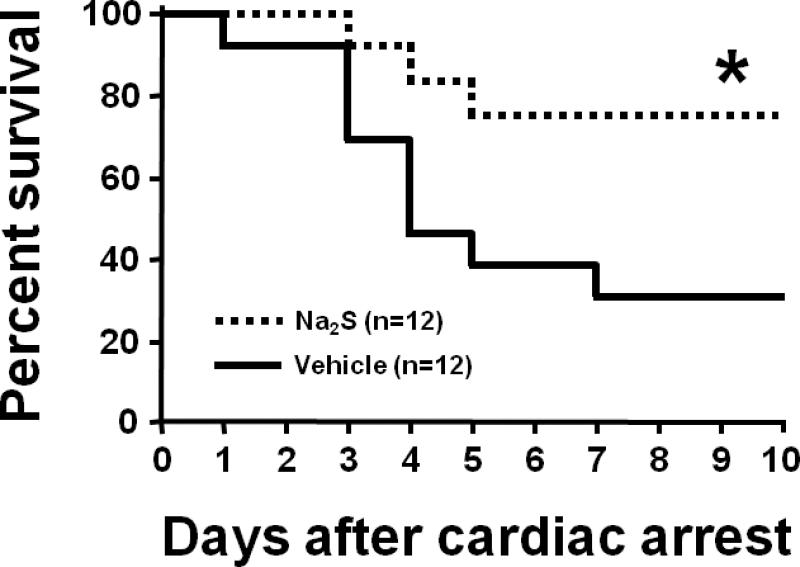

Na2S improves long-term survival rate after CA and CPR

ROSC was achieved in all mice after CPR. There was no difference between treatment groups in the total epinephrine dose, blood pressure, and heart rate 1h after CPR. CPR time to ROSC was slightly shorter in mice treated with Na2S (Supplemental Table 1 in the online-only supplementary data). Shortening of the arrest time from 8 to 7.5 min markedly prolonged survival time in all mice compared to our previous study.10 Administration of Na2S 1 min before CPR markedly improved long-term survival after CA/CPR in mice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Survival rate during the first 10 days after cardiac arrest (CA) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Vehicle, mice subjected to CA/CPR treated with vehicle. Na2S, mice subjected to CA/CPR treated with Na2S 1 min before CPR. *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle.

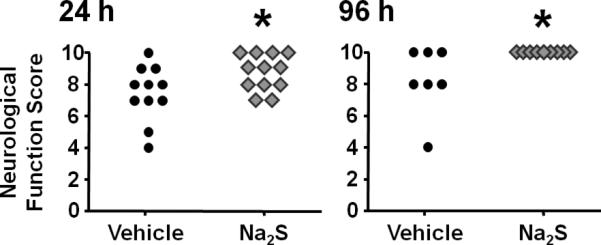

Na2S improves neurological function at 24 and 96 hours after CA and CPR

The neurological function score was better in surviving mice that were treated with Na2S than in mice that were treated with vehicle at 24 and 96h after CPR (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neurological function scores in surviving mice at 24 and 96h after cardiac arrest (CA) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Dead mice (indicated by score = 0) were excluded from the statistical analysis. *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle.

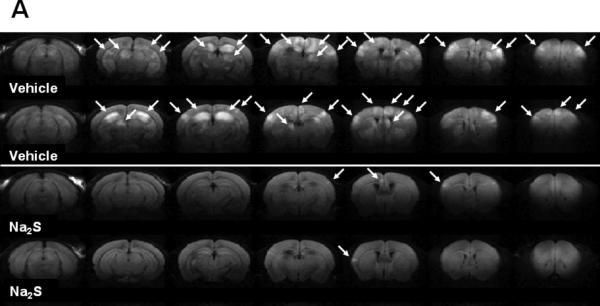

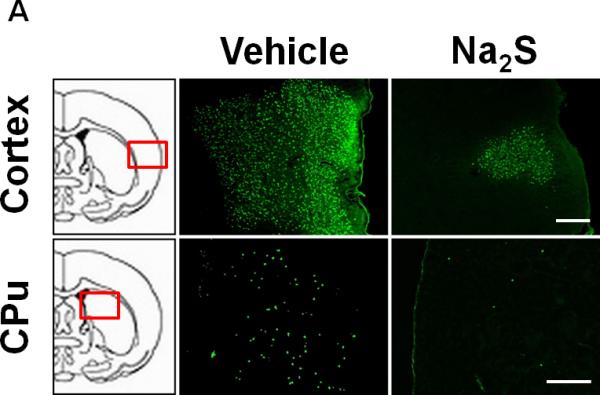

Na2S prevents water diffusion abnormality in the brain measured by MRI in live mice 24 hours after CA and CPR

MRI acquired 24h after CA/CPR in mice that were treated with vehicle showed areas of hyperintense DWI in brain suggesting the water diffusion abnormality (Fig. 3A). Administration of Na2S largely prevented the development of hyperintense DWI (Fig. 3A). The degree of abnormal water diffusion was quantitated by calculated average ADC in several ROI including ventral-lateral hippocampus (Hipp), caudoputamen (CPu), and lateral-frontal cortex (Cortex) (Fig. 3B). Na2S prevented the reduction of ADC values in Hipp and CPu (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that administration of Na2S prevents the development of the ischaemia-induced water diffusion abnormality in the brain 24h after CA/CPR.

Fig. 3.

Representative diffusion-weighted image (DWI) of mice 24h after cardiac arrest (CA) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). White arrows indicate the areas of hyperintense DWI (A). Representative MR images showing brain slices containing regions of interest [ROI]. Slice positions are identified in millimeters with respect to bregma in the coordinate space of the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas.14 Fig. 3Ba and 3Bb depict portions of ROI (red = lateral cortex; green = caudoputamen; blue = ventral-lateral hippocampus). Average ADC values of the slice plane for mice that treated with vehicle (n=7) [Vehicle]. Average ADC values of the slice plane for mice that treated with Na2S (n=8) [Na2S]. Color bar on the right side indicates color-code for ADC values (μm2/ms) (B). Average ADC values of each 3 dimensional ROI (Hipp = ventral-lateral hippocampus, CPu = caudoputamen, Cortex = lateral cortex) across all planes in mice that treated with vehicle (Vehicle, n=7) or Na2S (Na2S, n=8) after CA and CPR. *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle (C).

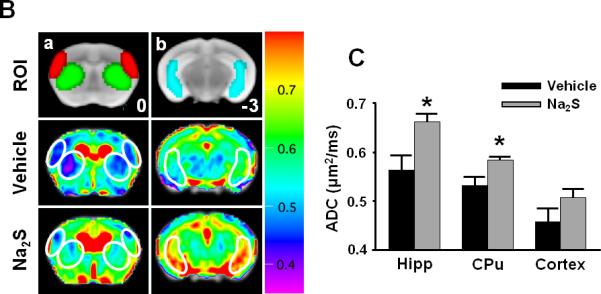

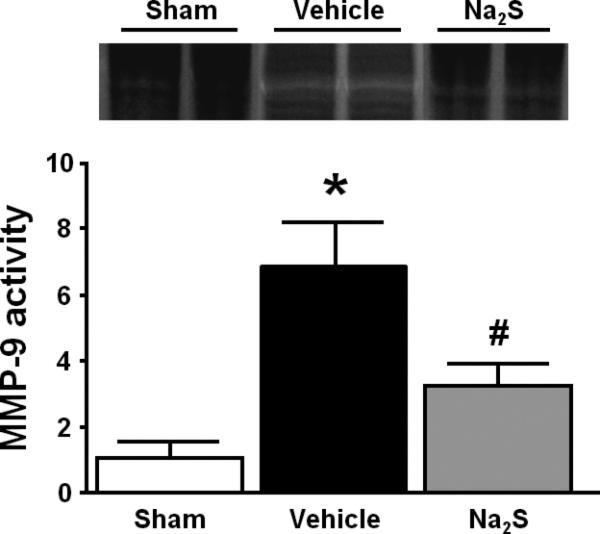

Na2S prevents the development of MMP-9 activation

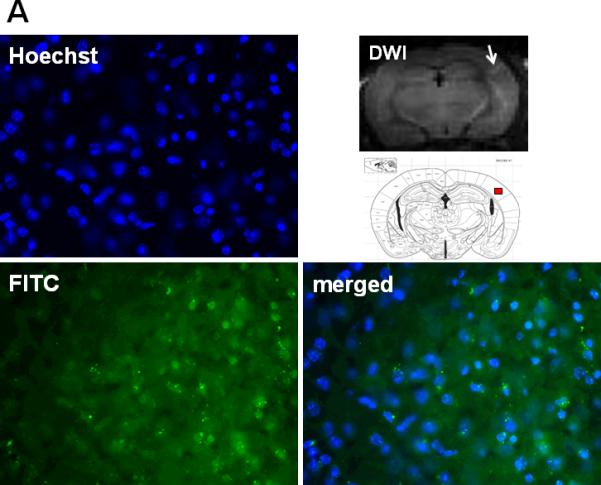

Gelatin zymography showed that MMP-9 activities were markedly increased 24h after CA/CPR in the brain of mice that were treated with vehicle. In contrast, mice that were treated with Na2S did not show the increase of MMP-9 activation in the brain (Fig. 4). In vivo hybridization of FITC-sODN-MMP-9 showed that MMP-9 mRNA expression spatially coincided with brain regions with hyperintense DWI in mice that were subjected to CA/CPR and treated with vehicle. Increased MMP-9 mRNA expression was demonstrated in the areas with hyperintense DWI (Fig. 5A), but not in areas with normal DWI (Fig 5B). No MMP-9 mRNA was detected in mice that were treated with Na2S at the initiation of CPR (data not shown). These results suggest that Na2S mitigates BBB disruption by inhibiting MMP-9 in the brain 24h after CA/CPR.

Fig. 4.

Representative gelatin zymography and quantified densitometry. Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) activity was evaluated by gelatin zymography employing the brain 24h after cardiac arrest (CA) and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). White bands represent areas of enzymatic activity of MMP-9. Mean intensity of zymography bands was normalized to sham control. Sham, sham-operated mice; Vehicle, mice treated with vehicle; Na2S, mice treated with Na2S 1 min before CPR. N=4 in each group. *P<0.05 vs. Sham. #P<0.05 vs. Vehicle.

Fig. 5.

Representative photomicrographs of brain sections subjected to in vivo hybridization with FITC-sODN-MMP-9 to determine the expression of elevated MMP-9 mRNA 24h after CA/CPR in vehicle-treated mice. Samples were counterstained with Hoechst for nuclei and merged images were shown. Brain regions of a vehicle-treated mice with hyperintense DWI indicated by a white arrow in the DWI image and red box in the brain atlas shown below (A). Brain regions of the same vehicle-treated mice with normal DWI signal indicated by a white arrow in the DWI image and green box in the brain atlas shown below (B).

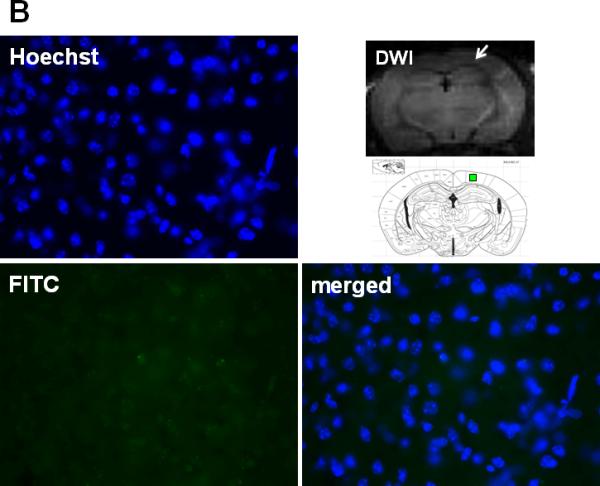

Na2S prevents neuronal degeneration after CA and CPR

The number of degenerated neurons in cortex and CPu was markedly increased at 72h after CA/CPR in vehicle-treated mice. Administration of Na2S attenuated CA/CPR-induced neurodegeneration in cortex and CPu (Fig. 6A and 6B). These results suggest that administration of Na2S prevents neurodegeneration after CA/CPR.

Fig. 6.

Representative photomicrographs of brain sections showing Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in cortex and caudoputamen (CPu) at 72h after CA/CPR. Vehicle, mice treated with vehicle; Na2S, mice treated with Na2S 1 min before CPR. Size bar=500 μm (A). Number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells per 1 mm2 in cortex and CPu in the brain. n=4 for each group. *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle (B).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that administration of Na2S at the initiation of CPR markedly improves neurological function and survival rate in mice after CA. Global brain ischaemia induced by CA/CPR induced abnormal water diffusion, and subsequent neuronal death, in the multiple regions of the brain including cortex, hippocampus, and caudoputamen. In mice subjected to CA/CPR, MMP-9 activity was increased in the brain homogenates and MMP-9 mRNA expression was found in the brain regions that exhibited abnormal water diffusion on MRI. Administration of Na2S attenuated the CA/CPR-induced water diffusion abnormality and neuronal degeneration after CA/CPR. Administration of Na2S also prevented MMP-9 activation in the brain regions with at 24h after CA/CPR. These observations suggest that administration of Na2S protects brain and improves survival by mitigating the MMP-9-mediated BBB disruption early after resuscitation.

Prognostic values of brain MRI have been suggested in animal models of CA,18 as well as in patients recovering from CA/CPR.19 In the present study, we observed that severity of water diffusion abnormality, demonstrated by hyperintense DWI on brain MRI in live mice, correlated with histological evidence of neuronal degeneration and poor survival 10 days after CA/CPR. These observations further support the prognostic utility of brain DWI after CA/CPR.

We have previously demonstrated that Na2S improves the neurological function and survival rate after 8 min of CA followed by CPR.10 The observation period in that study was, however, limited to only 24h after return of spontaneous circulation. The present study, on the other hand, revealed that Na2S prevents neurological dysfunction beyond this period of time, and improves survival rate at 10 days after CA/CPR in mice. Consistent with our findings, Knapp and colleagues recently reported that the administration of Na2S reduced the sensorimotor deficits 72h after CA/CPR in rats. However, administration of Na2S failed to improve survival rate in the study.20 Differences in the species and methods might explain the conflicting results of these studies. For example, Knapp and colleagues used 6 minutes arrest time, and vehicle-treated rats showed high survival rate (92%, 23 out of 25) at 7 days after CA/CPR. In contrast, we selected an arrest time of 7.5 min, resulting in a more severe ischaemic insult with a 7-day survival rate of only 33% (4 out of 12) in our vehicle-treated mice.

In contrast to the studies in rodents, Derwall and colleagues reported that two dosing regimen of Na2S (low dose: 0.3 mg/kg bolus followed by infusion at 0.3 mg/kg/h for 2h, high dose: 1 mg/kg bolus followed by infusion at 1 mg/kg/h for 2h) did not improve the resuscitatability and compromised post-resuscitation haemodynamics in swine after CA.21 While reasons for the apparent difference are likely to be multifactorial, higher cumulative doses of Na2S (0.9 and 3 mg/kg compared to 0.55 mg/kg in our studies in mice) and continuous Na2S administration in the studies by Derwall and colleagues may have adversely affected cardiovascular function. In fact, relatively narrow therapeutic range of Na2S has been reported in a murine model of cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion.8 Further studies in larger mammals are needed to determine the optimal dosing regimen of sulfide to improve outcomes after CA/CPR before clinical application of Na2S is considered.

It has been suggested that MMP-9 has deleterious roles in the early phase after cerebral ischaemia. MMP-9 disrupts the BBB by degrading the tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin and claudin-5) and basal lamina proteins (e.g., fibronectin, laminin, collagen, proteoglycans, and others), thereby leading to BBB leakage, leukocyte infiltration, brain edema, and hemorrhage.22,23 Studies have demonstrated that inhibition of MMP-9 activation, either by gene deletion or by administration of an inhibitor, is associated with attenuation of BBB leakage and reduced brain injury after cerebral ischaemia.24-26 In the present study, using an in vivo hybridization technique, we revealed that brain regions exhibiting increased MMP-9 mRNA expression spatially coincided with the brain areas with hyperintense DWI in mice subjected to CA/CPR and treated with vehicle. In contrast, administration of Na2S markedly prevented the development of hyperintense DWI and activity and expression of MMP-9. These observations suggest that protective effects of Na2S against water diffusion abnormality after CA/CPR are associated with inhibition of MMP-9.

The inhibitory effect of H2S donors (i.e., NaHS and Na2S) on MMP-9 activation has previously been reported in aortic banding-induced LV pressure overload,27 vascular remodeling,28 and hyperhomocysteinemia.29,30 For example, Tyagi and colleagues demonstrated that an imbalance between MMPs and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) activities, which regulate MMPs, can lead to MMP-9 activation and increased cerebral vascular permeability. On the other hand, H2S supplementation ameliorates cerebral vascular permeability via normalizing the MMP/TIMP ratio in the brain.29 It is conceivable that administration of Na2S at the time of CPR prevented BBB disruption via mechanisms related to normalization of MMP/TIMP ratio.

Studies have demonstrated that delayed neuronal death after cerebral ischaemia is significantly reduced in mice that are treated with the broad-spectrum metalloproteinase inhibitor BB-94 and in MMP-9-deficient mice.31 Previously, we reported that Na2S mitigates the post-resuscitation apoptosis in the brain, as indicated by decreased cleaved caspase 3-positive cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus at 24h after CA/CPR.10 In the present study, Fluoro-Jade B staining revealed that Na2S markedly prevented neuronal degeneration in cortex and CPu at 72h after CA/CPR, two regions of the brain in which hyperintense DWI were observed with MRI at 24h after CA/CPR. These observations further support the hypothesis that administration of Na2S prevents neuronal degeneration in the vulnerable regions of the brain after CA/CPR.

Conclusion

In summary, administration of Na2S 1 min before CPR markedly improved neurological function and survival rate at 10 days after CA/CPR by preventing water diffusion abnormality in the brain, potentially via inhibiting MMP-9 activation after resuscitation. The ability of Na2S to prevent the development of neurological dysfunction and promote survival rate in mice, if extrapolated to human beings, may be highly clinically relevant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIH R21AT004974 for Dr. Ren, DA026108, EB013768 and DA029889 (EUREKA award) and AHA 09GRNT2060416 to Dr. Liu, and NIH HL71987 and GM79360 to Dr. Ichinose. The authors thank Ikaria Inc. for generously providing IK-1001.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors verify that no competing financial interests exist.

Reference List

- 1.Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. Part 1: Executive Summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S640–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild Therapeutic Hypothermia to Improve the Neurologic Outcome after Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:549–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of Comatose Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest with Induced Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. For the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2009 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roine RO, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1993;269:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashiba M, Kajimura M, Goda N, Suematsu M. From O2 to H2S: a landscape view of gas biology. Keio J Med. 2002;51:1–10. doi: 10.2302/kjm.51.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–35. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15560–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sodha NR, Clements RT, Feng J, et al. The effects of therapeutic sulfide on myocardial apoptosis in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:906–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minamishima S, Bougaki M, Sips PY, et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Improves Survival After Cardiac Arrest and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation via a Nitric Oxide Synthase 3-Dependent Mechanism in Mice. Circulation. 2009;120:888–96. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.833491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishida T, Yu JD, Minamishima S, et al. Protective effects of nitric oxide synthase 3 and soluble guanylate cyclase on the outcome of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in mice. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:256–62. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192face. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: Adult Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support. Circulation. 2010;122:S729–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abella BS, Zhao D, Alvarado J, Hamann K, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB. Intra-arrest cooling improves outcomes in a murine cardiac arrest model. Circulation. 2004;109:2786–91. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131940.19833.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–76. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tejima E, Zhao BQ, Tsuji K, et al. Astrocytic induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and edema in brain hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;27:460–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CH, You Z, Liu CM, et al. Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Reversal by Gene Knockdown of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Activities in Live Animal Brains. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3508–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5332-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Research. 2000;874:123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu Y, Liachenko SM, Tang P, Chan PH. Faster Recovery of Cerebral Perfusion in SOD1-Overexpressed Rats After Cardiac Arrest and Resuscitation. Stroke. 2009;40:2512–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.548453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wijman CA, Mlynash M, Caulfield AF, et al. Prognostic value of brain diffusion-weighted imaging after cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:394–402. doi: 10.1002/ana.21632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp J, Heinzmann A, Schneider A, et al. Hypothermia and neuroprotection by sulfide after cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1076–80. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derwall M, Westerkamp M, Lower C, et al. Hydrogen sulfide does not increase resuscitability in a porcine model of prolonged cardiac arrest. Shock. 2010;34:190–5. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181d0ee3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA) and Matrix Metalloproteinases in the Pathogenesis of Stroke: Therapeutic Strategies. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2008;7:243–53. doi: 10.2174/187152708784936608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham LA, Wetzel M, Rosenberg GA. Multiple roles for MMPs and TIMPs in cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2005;50:329–39. doi: 10.1002/glia.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romanic AM, White RF, Arleth AJ, Ohlstein EH, Barone FC, Dawson VL. Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression Increases After Cerebral Focal Ischemia in Rats: Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Reduces Infarct Size. Stroke. 1998;29:1020–30. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.5.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asahi M, Asahi K, Jung JC, del Zoppo GJ, Fini ME, Lo EH. Role for Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 After Focal Cerebral Ischemia: Effects of Gene Knockout and Enzyme Inhibition With BB-94. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1681–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svedin P, Hagberg H, Savman K, Zhu C, Mallard C. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Gene Knock-out Protects the Immature Brain after Cerebral Hypoxia-Ischemia. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1511–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Givvimani S, Munjal C, Gargoum R, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates transition from compensatory hypertrophy to heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:1093–100. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01064.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vacek T, Gillespie W, Tyagi N, Vacek J, Tyagi S. Hydrogen sulfide protects against vascular remodeling from endothelial damage. Amino Acids. 2010;39:1161–9. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0550-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyagi N, Givvimani S, Qipshidze N, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity and neurovascular permeability in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen U, Munjal C, Qipshidze N, Abe O, Gargoum R, Tyagi SC. Hydrogen Sulfide Regulates Homocysteine-Mediated Glomerulosclerosis. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:442–55. doi: 10.1159/000296717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SR, Tsuji K, Lee SR, Lo EH. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Delayed Neuronal Damage after Transient Global Cerebral Ischemia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:671–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4243-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.