Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether participants of a dental practice-based research network (PBRN) differ in their level of oral health impact as measured by the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) questionnaire.

Methods

A total of 2410 patients contributed 2432 OHIP measurements (median age = 43 years; interquartile range = 28) were enrolled in four dental studies. All participants completed the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) during a baseline visit. The main outcome of the current study was the level of oral health impact, defined as follows: no impact (“Never” reported on all items); low (“Occasionally” or “Hardly ever” as the greatest frequency score reported on any item); and high (“Fairly often” or “Very often” as the greatest frequency reported on any item). Polychotomous logistic regression was used to develop a predictive model for the level of oral health impact considering the following predictors: patient’s age, gender, race, practice location, type of dentist, and number of years the enrolling dentist has been practicing.

Results

A high level of oral health impacts was reported in 8% of the sample; almost a third (29%) of the sample reported a low level of impacts, and 63% had no oral health impacts. The prevalence of impacts differed significantly across protocols (P<0.001). Females were more likely to be in the high oral impact group than the no impact group compared to males (OR=1.46; 95% CI= 1.06–1.99). African-Americans were more likely to report high oral impacts when compared to other racial/ethnic groups (OR=2.11; 95% CI = 1.26–3.55). Protective effects for being in the high or in the low impact groups were observed among patients enrolled by a solo practice (P<0.001) or by more experienced dentists (P=0.01). A small but highly significant statistical association was obtained for patient age (P<0.001). In the multivariate model, patient’s age, practice size and gender were found to jointly be significant predictors of oral health impact level.

Conclusions

Patients’ subjective report of oral health impact in the clinical setting is of importance for their health. In the context of a dental PBRN, the report of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) was different across four dental studies. The observed findings validate the differential impact that oral health has on the patients’ perception of OHRQoL particularly among specific groups. Similar investigations to elucidate the factors associated with patient’s report of quality of life are warranted.

Keywords: Oral-Health Impact, OHRQoL, Dental PBRN, OHIP-14, Patient Reported Outcomes, Subjective Health

Introduction

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), such as patient satisfaction, quality of life (QoL), and well-being, have become increasingly relevant in clinical practice (1–3). For instance, quality of life is recognized in the medical literature as a term used by patients to acknowledge what is in their own best interest (4). In dental practice, a multidimensional construct known as oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), includes domains of physical, emotional, and social functioning, and focuses on the impact oral health status has on overall QoL (5). In dental practice, OHRQoL could provide valuable information to enhance patients’ well-being as a result of a dental treatment (6–7). Assessing patients’ subjective experiences to determine the impact of oral health conditions on well-being and self-esteem could improve clinical interventions and enhance QoL (8).

The Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) (9) is a self-reported validated measure to assess negative oral impacts on seven conceptual dimensions of impact: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. The OHIP-14 scale has been adapted and validated to assess OHRQoL among school-aged children in the United States (US) (10–11). The NHANES 2003–2004 data, reported that approximately 15% of adults living in the US have an oral health problem that adversely impacts their QoL (12).

Compared to adults in the US general population, patient samples are more likely to report greater oral health impact across specific dental diagnoses or conditions such as temporomandibular disorders, dentin hypersensitivity, and third molar surgery (13–16). Gagliardi and collaborators (2008), using a sample of adults aged 75 years and older, reported discomfort while eating and painful aching as the most prevalent impacts reported on the OHIP-14 (17). In addition, for patients receiving third molar extractions, psychosocial impacts, such as difficulty relaxing and feeling self-conscious, were commonly reported as common oral impacts (16). Among the clinical characteristics associated with oral impacts, the number of teeth requiring extraction or endodontic treatment and the number of decayed teeth are factors associated with oral impact levels (18,19).

Empirical evidence has reported on the association between sociodemographic characteristics and poor OHRQoL. The effects of age, ethnicity, cultural background, gender and educational status on OHRQoL have had mixed results (7,19). Steele and collaborators examined the association between age and loss of teeth on two national samples from Australia and the United Kingdom (UK) (19). The investigators found that age, number of teeth lost and cultural background were associated with OHRQoL; increasing age was associated with better mean impact scores among adults 70 years or older in both countries than those aged 30–49 years. The work of MacEntee and collaborators with a group of 24 Canadian elders suggests that among the elders a substantial part of successful aging is to adapt to oral disorders (20). This lower expectation among the elder may also reflect a form of fatalism (21) or perhaps a greater resilience than younger adult samples (22).

In the area of ethnicity, Steele et al. found that tooth loss had a differential effect on the OHRQoL score in Australia and the UK, after adjusting for age (19). First-generation immigrants reported worse overall scores than the Australian and British born counterparts. Another investigation in a group of 733 low-income elders of ethnic minority groups in the US and in Canada found that ethnicity, being foreign-born, gender, years since immigrating, number of carious roots, and periodontal status were significant predictors of poor OHRQoL (23). Recently, the “Latino paradox” – as it applies to QoL among this ethnic group – showed that being Latino had a protective effect that was further modified by nativity status, suggesting that Latino immigrants have a better OHRQoL than their US born Latino counterparts (24). In general, limited access to dental care in the US among those with no and/or limited health insurance increases the odds that a patient will report lower OHRQoL; thus, the improvement of OHRQoL remains an area of public concern among these underserved populations (25).

The extensive work by MacGrath and Bedi in random probability samples has identified disparities in OHRQoL in populations’ subgroups (26). In Britain a national survey of 2,667 households found that almost three-quarters (73%) reported that their oral health affects their QoL (27). In a nation-wide survey of 1,865 adults in Britain (1,049 women and 816 men), women significantly reported oral health as causing more pain, embarrassment and less financial success compared to men (26). On the other hand, women also reported oral health as a factor that positively enhances their QoL, moods, appearance and general well-being. Empirical evidence on gender has found that women are more likely to perceive oral health as reducing or adding to their QoL compared to men (26). These results were consistent with those reported in a large national cohort sample of 87,137 adults living in Thailand (28). The study found that females reported more problems with chewing, social interaction, and pain.

Although education was not measured in the present study, previous research has found mixed findings to its association with OHRQoL (29,16). Investigations like the one by Tsakos and colleagues in a community sample of adults living in London found lower levels of education associated with poor OHRQoL (29). In Australia, survey participants with education of 9 years or less rated their oral health as fair or poor more frequently than their more educated counterparts (30). Conversely, according to Slade et al. (16) educational level was not associated with reporting oral impacts fairly often or very often in a sample of 480 patients seeking removal of their third molars. In addition, little is known on the effect that variables associated with the dental practice setting (i.e., type of practice, practice location) have on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as OHRQoL (31). The examination of these variables and their value for general dental practitioners is an emergent area that merits more attention (26).

The information obtained from OHRQoL research provides dental practitioners with context and perspective on the extent to which oral conditions can affect a patient’s ability to function normally (15,32). Dental practice-based research networks (PBRNs) are one of the recent major initiatives to address clinical challenges experienced by private dental practitioners in their clinical practices and to accelerate the implementation of research into practice (33–34). Dental PBRNs provide an optimal setting to elucidate how oral treatment translates into better OHRQoL. The assessment of OHRQoL in the practice-based setting can inform the decision-making process that takes place between the patient and dental practitioner and at the same time implement dental research into practice to enhance patient-centered care.

The present study was designed to determine whether participants of a particular dental PBRN known as PEARL (Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning) differ in their level of oral health impact. We hypothesized that OHRQoL will be different among study participants depending on socio-demographic characteristics. Despite the evidence reported in European national surveys, scant data exist regarding OHRQoL assessments among private dental practices, particularly in the setting of dental PBRNs in the US. Thus, the present investigation will be among the pioneering studies examining OHRQoL in dental PBRNs.

Methods

Study Design

This analysis uses baseline data from four PEARL studies: two prospective observational studies, one retrospective study, and one randomized controlled trial. The data obtained were collected from a convenience sample of participants whose dental practitioners are members of the PEARL Network. The following briefly describes the four PEARL research studies:

Outcomes of Endodontic Treatment and Restoration (Endo) - The objective of this retrospective study was to evaluate the 3 to 5 year outcomes and risk factors associated with the endodontic treatment and restoration of nonvital teeth in general practices. Note that the endodontic therapy may have been performed by a specialist, but the enrolling P-I performed the subsequent restoration. This study contributes OHIP data on 1278 patients to the current analysis.

Post-Operative Hypersensitivity (POH) after Placement of Resin-Based Composite (RBC) Restorations (Shallow Caries) - The objectives of the study were to (a) determine the incidence and severity of POH as reported by patients who receive RBC restorations; (b) measure the association between POH and restoration width and depth, dentin caries activity, and restorative materials and techniques; and, (c) assess RBC restoration treatment and its impact on OHRQoL as reported by patients. In this shallow caries study, the lesions were not required to be visible on radiograph; however, if the caries were visible, they must have been less than or equal to one half the distance from the dento-enamel junction (DEJ) to the pulp. This study contributes OHIP scores from 607 participants to the current analyses of baseline OHRQoL.

Complete vs. Partial Removal of Deep Caries (Deep Caries) - The objectives were to (a) compare the tooth vitality at one year post treatment of complete vs. partial caries removal in deep Class I and II lesions; (b) assess the effects of deep caries treatment on patients’ POH and OHRQoL; and (c) evaluate the effectiveness of cavity lining and bonding techniques. Eligibility criteria required all lesions to be confirmed via radiograph and at least one half the distance from the DEJ to the pulp, suggesting a possibly poorer QoL than in the shallow caries study described above. This study contributes data from 279 participants.

Noncarious Cervical Lesion Outcomes (NCL) - This study is a randomized controlled trial to determine the comparative effectiveness of three treatments for hypersensitive noncarious cervical lesions (NCLs): chemoactive dentifrice use, dentin bonding agent with sealing, and flowable resin–based composite restoration. The primary outcomes of this study are the reduction and/or elimination of hypersensitivity and the effect of treatment as measured by subject-reported outcomes. This study requires that patients report at least three on a 0–10 pain scale in response to an air blast prior to treatment. This eligibility criterion suggests enrolled participants would have substantial hypersensitivity and potential oral health impacts. The NCL study contributes OHIP data from 268 patients.

Procedures

A total of 190 dental practices were invited to participate in the four PEARL Network studies. Of those, 103 were activated and 85 proceeded to enroll patients into these four research protocols during the period of 11/14/2006 through 9/16/2010. Dental practices that were not activated were either not interested in participating in any of the studies or doubted their ability to accrue subjects into the studies. A total of 2410 patients were recruited across the participating PEARL practices and had baseline OHIP measurements; 22 of these patients were enrolled in two of the four protocols and thus contribute two different OHIP measurements to the current analyses. Patients were recruited locally at each dental practice. The New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all four PEARL research protocols, each of which included the OHIP-14 questionnaire at baseline and follow-up visits. Patients were asked for their consent and/or pediatric assent for all studies during enrollment.

Study Measures

The main outcome of this study was the level of oral health impacts using the OHIP-14 (9). The OHIP-14 scale measures the frequency of experiencing oral impacts using a 5-point ordinal scale (0-“Never”, 1-“Hardly ever”, 2-“Occasionally”, 3-“Fairly often”, and 4-“Very often”). An ordinal summary measure of the level of oral health impact was developed as follows: no impact (“Never” on all 14 items); low impact (the greatest frequency of experienced impact reported over all items is either “Hardly ever” or “Occasionally”); and high impact (the greatest experienced impact frequency on any item is either “Fairly often” or “Very often”). The current data was highly skewed to zero (i.e. no impacts), thus we discretized the OHIP score in this manner to differentiate the group with no impacts, without losing information on the magnitude of the OHIP score in those who did experience some impact. This ordinal measure of oral impact was used to determine the predictors of having low or high oral health impacts relative to no OHRQoL impacts.

In addition, to describe and explain the findings of the present investigation, the prevalence of oral impacts, the total OHIP score, OHIP severity, and the OHIP dimension-specific scores were measured. For all these measures, higher scores indicate poorer OHRQoL.

Prevalence of oral impacts was defined as the percentage of patients responding “Fairly often” or “Very often” to at least one of the items (12, 35).

OHIP severity is the sum of all ordinal responses (0–4) across all the 14 items; total scores range from 0 to 56.

OHIP dimension-specific scores are the sum of all ordinal (0–4) responses over both items within each of the following seven dimensions: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. Each dimension is the sum of two questions, thus each score ranges from 0–8. The percent of patients with any dimension-specific impact is defined as the proportion of patients whose dimension-specific score is non-zero.

Patients completed the OHIP questionnaire via paper questionnaires in the dental office, with the responses later entered into the electronic data capture (EDC) system by practice staff. Socio-demographic information (gender, age, and ethnicity/race) was directly entered into the EDC system by practice staff. Dental practitioner information was collected from the Practitioner-Investigator (P-I) Profile form (dentist type, practice location and size, years P-I has been in practice) which is completed prior to admittance into the PEARL Network.

Statistical Analysis

Patients enrolled in two protocols represent less than one percent of the participants considered in these analyses, thus the correlation in their OHIP measurements will have minimal, if any, effect on the results and was therefore ignored. Contingency table analyses (χ2 tests) were used in evaluating the differences across protocols for the following categorical variables: gender, ethnicity/race, practice location, type of dentist (generalist or specialist), practice size, prevalence of oral health impacts and dimension-specific OHIP scores. Quantile regression was used to assess whether the following continuous variables differ across protocol: patient age, number of years P-I has been in practice, and OHIP severity. Standard linear regressions for assessing differences across protocols were not possible since all continuous variables were highly skewed; thus, quantile regression was used and the data were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Categorical covariates are collapsed for all of the following models based on the categorization yielding the best fit (in the polychotomous regression) via Akaike’s Information Criterion. The relationships between prevalence of oral health impacts and patient and practice characteristics were assessed using univariate logistic regression. Since study protocol is a potential confounder of these univariate relationships, the logistic regression analyses were performed within each study and also stratified by (i.e., conditional on) protocol. The association between oral health impact level (none, low, high) and characteristics of the patient and practice were evaluated using polychotomous logistic regression, again stratifying by the potential confounder of protocol participation. The resulting odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) capture the following comparisons: (a) odds of low impact vs. odds of no impact, and (b) odds of a high impact vs. odds of no impact at all. Use of logistic regression in this context will not allow interpretation of the resulting odds ratios as approximate risk ratios since the outcomes are not rare, however these regression models are the most suited to handle this type of data. For the polychotomous logistic regression, univariate associations were evaluated and a multivariate model was built in a stepwise fashion with an entry/exit P-value of 0.05. SAS 9.2 was used to conduct all statistical analyses SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA; the following SAS procedures were utilized: freq, univariate, logistic, quantreg, phreg and surveylogistic. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

More than half of the sample (53%) came from the endodontic treatment protocol, followed by the shallow caries protocol (25%). The deep caries protocol and the non-carious cervical lesion protocols provided the same percentage of participants (11%). Table 1 shows the patient and practice characteristics within and across protocols. The total sample consisted of 2,432 OHIP measurements from 2410 participants with a median age of 43 years (IQR=28) at the time of measurement; 58% of measurements were from female and 74% were from self-reported whites. Most of the patients were enrolled by suburban practices (65%), and the vast majority was enrolled by generalists (99%). Due to the very small number of patients enrolled by specialists, dentist type will be excluded from all subsequent modeling.

Table 1.

Patient and practice characteristics within and across protocols.

| Characteristic | Values | Overall (N=2432) | PEARL Protocol | Difference Across Protocols | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo (N=1278) | Shallow Caries (N=607) | Deep Caries (N=279) | NCL (N=268) | ||||

| Frequency (%) | P value | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 1014 (42%) | 541 (42%) | 247 (41%) | 135 (48%) | 91 (34%) | P=0.007 |

| Female | 1418 (58%) | 737 (58%) | 360 (59%) | 144 (52%) | 177 (66%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Ethnicity/Race | White | 1712 (74%) | 994 (82%) | 422 (72%) | 124 (46%) | 172 (66%) | P<0.001 |

| African American | 142 (6%) | 48 (4%) | 40 (7%) | 29 (11%) | 25 (10%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 300 (13%) | 88 (7%) | 65 (11%) | 100 (37%) | 47 (18%) | ||

| Other* | 172 (7%) | 81 (7%) | 57 (10%) | 16 (6%) | 18 (7%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Practice Location | Rural | 266 (11%) | 140 (11%) | 28 (5%) | 58 (21%) | 40 (15%) | P<0.001 |

| Urban | 590 (24%) | 250 (20%) | 153 (25%) | 142 (51%) | 45 (17%) | ||

| Suburban | 1576 (65%) | 888 (69%) | 426 (70%) | 79 (28%) | 183 (68%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Dentist Type | Generalist | 2406 (99%) | 1266 (99%) | 603 (99%) | 279 (100%) | 258 (96%) | P<0.001** |

| Specialist | 26 (1%) | 12 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (4%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Practice Size | Solo Practice | 1172 (48%) | 640 (50%) | 386 (64%) | 63 (23%) | 83 (31%) | P<0.001 |

| Larger Practice | 1260 (52%) | 638 (50%) | 221 (36%) | 216 (77%) | 185 (69%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Median (IQR) | |||||||

| Patient’s Age (years) | 43 (28) | 51 (15) | 25 (15) | 17 (13) | 47 (14) | P<0.001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Years in Practice | 23 (9) | 23 (9) | 24 (11) | 17 (17) | 23 (9) | P<0.001 | |

Other includes Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native and Multiracial patients.

Due to small cell counts, the P value is from Fisher’s exact test.

Table 2 summarizes the various OHIP-14 measures for each protocol. The prevalence of oral impacts was 8% of the sample with significant differences across protocols (P<0.001). Patients participating in either the deep caries study or the NCL study had the highest prevalence of oral health impacts (24% and 25%, respectively). Patients whose study treatments were for shallow caries or endodontic therapy reported the lowest prevalence of impacts (5% and 3%, respectively). Similarly, the percent of patients reporting at least one impact on the physical pain dimension was far greater in the deep caries (55%) and in the NCL studies (85%) than in the endodontic (17%) and shallow caries (28%) studies.

Table 2.

Summary of oral health-related quality of life measurements within and across PEARL protocols.

| OHIP-14 Measure | Possible Range | PEARL Protocol | Difference Across Protocols | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=2432) | Endo (N=1278) | Shallow Caries (N=607) | Deep Caries (N=279) | NCL (N=268) | |||

| Frequency (%) | P value | ||||||

| Prevalence1 | 0, 1 | 198 (8%) | 33 (3%) | 33 (5%) | 66 (24%) | 66 (25%) | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Median (IQR) | |||||||

| OHIP Severity2 | 0 – 56 | 0 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (2) | 2 (9) | 6 (10) | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Dimension3 | % with Any Impact (Observed Range of Scores) | ||||||

| Functional Limitation | 0 – 8 | 6% (0–6) | 2% (0–6) | 3% (0–3) | 19% (0–4) | 21% (0–6) | P<0.001 |

| Physical Pain | 0 – 8 | 31% (0–8) | 17% (0–8) | 28% (0–7) | 55% (0–8) | 85% (0–8) | P<0.001 |

| Psychological Discomfort | 0 – 8 | 19% (0–8) | 10% (0–6) | 16% (0–8) | 33% (0–8) | 57% (0–8) | P<0.001 |

| Physical Disability | 0 – 8 | 13% (0–8) | 4% (0–4) | 8% (0–6) | 33% (0–8) | 48% (0–8) | P<0.001 |

| Psychological Disability | 0 – 8 | 14% (0–8) | 5% (0–5) | 10% (0–8) | 33% (0–8) | 42% (0–5) | P<0.001 |

| Social Disability | 0 – 8 | 8% (0–8) | 3% (0–4) | 5% (0–4) | 25% (0–8) | 24% (0–5) | P<0.001 |

| Handicap | 0 – 8 | 8% (0–7) | 3% (0–4) | 3% (0–4) | 23% (0–7) | 25% (0–6) | P<0.001 |

Prevalence is the proportion of patients responding “Fairly often” or “Very often” to one or more of the 14 items.

OHIP severity is defined as the sum of all ordinal responses across all the 14 items.

Dimension-specific scores are defined as the sum of responses for both items within that dimension. Percent with any impact is proportion of patients whose dimension-specific scores are non-zero.

Table 3 shows the logistic regression results assessing the relationship between prevalence of oral health impacts and the patient and practice characteristics within protocol as well as stratified by protocol. For binary characteristics, categories expressed as A vs. B denote that A is the comparator group and B is the referent group. Compared to males, females were more likely to report oral health impacts after adjusting for protocol (OR=1.56; 95% CI: 1.12–2.16; P=0.01). Patients whose enrolling practices were located in rural or suburban regions were more likely to report oral impacts (OR=1.73; 95% CI: 1.17–2.54; P=0.01) than those in urban areas.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the prevalence* of oral health impacts within and across protocols.

| Characteristic** | PEARL Protocol | Stratifying by Protocol OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo OR (95% CI) | Shallow Caries OR (95% CI) | Deep Caries OR (95% CI) | NCL OR (95% CI) | ||

| P value | P value | P value | P value | P value | |

| Patient’s Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) P=0.47 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) P=0.45 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) P=0.29 | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) P=0.14 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) P=0.17 |

|

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female vs. Male | 1.13 (0.56–2.30) P=0.73 | 1.21 (0.59–2.51) P=0.60 | 1.61 (0.92–2.83) P=0.09 | 2.29 (1.19–4.40) P=0.01 | 1.56 (1.12–2.16) P=0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity/Race | |||||

| AA vs. Not AA*** | 0.78 (0.10–5.81) P=0.80 | 1.39 (0.41–4.77) P=0.62 | 0.84 (0.33–2.16) P=0.71 | 2.21 (0.94–5.19) P=0.08 | 1.31 (0.77–2.22) P=0.33 |

|

| |||||

| Practice Location | |||||

| Rural/Suburban vs. Urban | 8.00 (1.09–58.83) P<0.01 | 0.66 (0.31–1.39) P=0.28 | 2.00 (1.14–3.52) P=0.02 | 1.95 (0.83–4.61) P=0.11 | 1.73 (1.17–2.54) P<0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Practice Size**** | |||||

| Solo vs. Large Practice | 1.55 (0.77–3.15) P=0.22 | 0.77 (0.38–1.56) P=0.46 | 1.55 (0.83–2.91) P=0.18 | 0.87 (0.47–1.60) P=0.66 | 1.13 (0.81–1.57) P=0.48 |

|

| |||||

| Years in Practice | 1.08 (1.01–1.14) P=0.01 | 0.98 (0.92–1.03) P=0.38 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) P=0.07 | 0.94 (0.89–1.01) P=0.07 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) P=0.15 |

Prevalence is the proportion of patients responding “Fairly often” or “Very often” to one or more of the 14 items.

Categories A vs. B denote comparator group A and referent group B.

AA denotes African American.

Large practice refers to practices with more than one dentist.

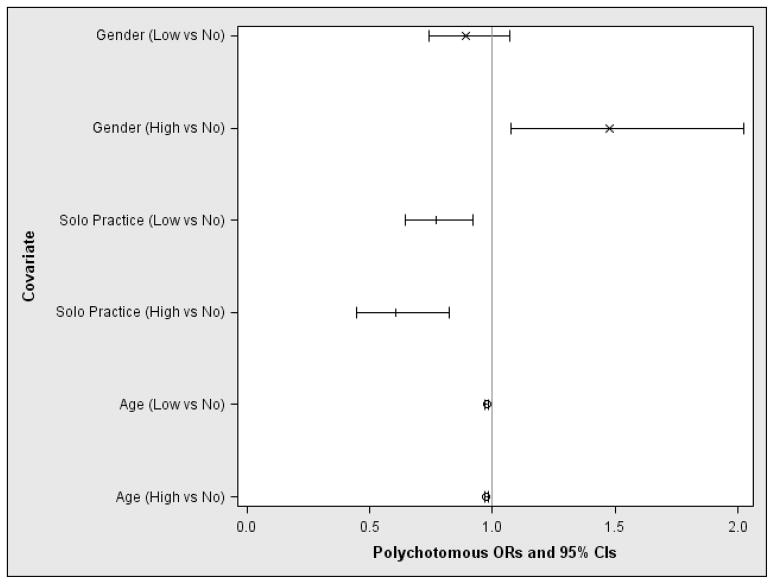

The univariate polychotomous regressions for the level of oral health impacts (no, low or high impact) are presented in Table 4, where all models are stratified by protocol. Females were more likely than males to report high level of oral impacts (OR=1.46; 95% CI: 1.06–1.99). The proportion of patients enrolled by rural or suburban practices was higher in the low or high levels of oral impacts groups than their urban counterparts, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (P=0.46). In the final multivariate polychotomous logistic regression model, the probabilities of being in the no impact, low, or high impact levels are summarized in Figure 1. This final model contains the following variables: patient’s age (P<0.001), practice size (P=0.001), and gender (P=0.01). Compared to males, females were more likely to be in the high impact level group as opposed to the no impact level group (OR=1.47, 95% CI: 1.08–2.02, P=0.02), yet there was no statistically significant association for the low vs. no impact groups (P=0.23). However, young patients and those who were enrolled by a practice with only one dentist were less likely to report a high level of oral impact compared to the no impact group (OR=0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99, P<0.001 and OR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.45–0.82, P=0.001). Age and enrolling practice size are also statistically significantly associated with reports of low impact level relative to the no impact group (OR=0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.98, P<0.001 and OR=0.77, 95% CI: 0.64–0.92, P=0.005, respectively). While there is a clear univariate association between levels of oral health impact and both ethnicity/race and P-I years of experience, neither remained in the final multivariate predictive model.

Table 4.

Levels of oral health impacts: summary and univariate polychotomous results stratifying by protocol.

| No Impact | Low Impact | High Impact | Low vs. No Impact | High vs. No Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Overall* | 1523 (63%) | 711 (29%) | 198 (8%) | ||

| Endo Study | 1004 (79%) | 241 (19%) | 33 (3%) | ||

| Shallow Caries Study | 389 (64%) | 185 (30%) | 33 (5%) | ||

| Deep Caries Study | 95 (34%) | 118 (42%) | 66 (24%) | ||

| NCL Study | 35 (13%) | 167 (62%) | 66 (25%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | P=0.01 | ||||

| Female | 890 (63%) | 395 (28%) | 133 (9%) | 0.89 (0.74–1.06) | 1.46 (1.06–1.99) |

| Male | 633 (62%) | 316 (31%) | 65 (6%) | - | |

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity/Race | P=0.02 | ||||

| African American | 75 (53%) | 47 (33%) | 20 (14%) | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 2.11 (1.26–3.55) |

| White | 1106 (65%) | 479 (28%) | 127 (7%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 168 (56%) | 101 (34%) | 31 (10%) | - | |

| Other** | 96 (56%) | 61 (35%) | 15 (9%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Practice Location*** | P=0.46 | ||||

| Rural | 145 (55%) | 87 (33%) | 34 (13%) | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) | 1.17 (0.82–1.67) |

| Suburban | 996 (63%) | 460 (29%) | 120 (8%) | ||

| Urban | 382 (65%) | 164 (28%) | 44 (7%) | - | |

|

| |||||

| Dentist Type | |||||

| Specialist | 10 (38%) | 9 (35%) | 7 (27%) | N/A | |

| Generalist | 1513 (63%) | 702 (29%) | 191 (8%) | ||

|

| |||||

| Practice Size | P<0.001 | ||||

| Solo practice | 780 (67%) | 315 (27%) | 77 (7%) | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) | 0.61 (0.45–0.82) |

| Large practice | 743 (59%) | 396 (31%) | 121 (10%) | - | |

|

| |||||

| Median (IQR) | |||||

| Patient’s Age | 46 (26) | 38 (28) | 39 (29) | P<0.001 | |

| 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Years in Practice | 23 (9) | 23 (9) | 23 (10) | P=0.01 | |

| 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | ||||

N/A denotes not applicable; - denotes referent category.

For the level of impact, the OHIP-14 scale was recoded into three categories: no impact (“Never” on all items), low (maximum of “Hardly ever”/”Occasionally” over all items), and high (maximum of “Fairly often”/ “Very often” over all items).

Other includes Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native and Multiracial patients.

ORs are for indicator of suburban or rural practices versus urban ones.

Figure 1.

Multivariate prediction model for the level of oral health impacts.

Discussion

The most significant clinical finding of the present study is that after controlling for protocol participation, patients’ gender, age, race/ethnicity as well as clinical characteristics remained significant predictors of oral health impact level. This study assessed oral health impacts among patients in a dental practice-based research network known as PEARL. The literature on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as OHRQoL, although emergent, is still scant in the private dental practice setting. The OHIP-14 assesses how an oral condition impacts a patient’s ability to pronounce words, eat and taste food, etc. (9). The effect of oral conditions on a person’s life could have a substantial effect on the decision-making process and adherence to dental treatment. Previous research has examined OHRQoL with population-based samples (36) and with patients in a clinical setting (17); however, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report oral health impacts in a dental PBRN setting across several oral health studies.

The oral impacts reported in this study were lower than those reported in other clinical samples (18) and in the general population (12, 15, 37). Several factors might have contributed to this difference. Although speculative, it might be that since the majority of respondents were patients of suburban private dental practices, the group of participants in PEARL studies has better access to dental care and higher utilization of dental services compared to other studies. In addition, the socio-economic status of these participants might increase their access to dental care. Of importance, these previous investigations treated different oral conditions, such as third molar extractions and temporomandibular disorders, than those presented in this investigation. Nonetheless, we found a differential impact of OHRQoL among participants in the endo study, shallow caries study and those in the noncarious cervical lesion and the deep caries studies. The prevalence of oral impacts was much higher among those in the latter studies suggesting an effect of the dental condition related to their study participation on their physical and psychological well-being as reported by the patient. In addition, the different eligibility criteria and study designs across protocols might have had a potential effect on the results. For example, the endodontic outcomes study was a retrospective study whereas the noncarious cervical lesion study was prospective and required sensitivity at baseline.

The gender findings reported here do not compare with the findings of Bekes and colleagues (14). They found that women with dentin hypersensitivity had more oral health impacts than men, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, in a population sample, a study found that women were more likely to report oral health complaints than men (12). Our findings showed that African Americans were twice as likely to be in the high impact group compared to their non-African American counterparts suggesting an oral health inequality in the prevalence of oral health impacts. Other investigations have observed significant race/ethnic differences for older African Americans compared to whites (12,16,38).

In our analyses, a statistically significant but small protective effect per one year increase in age was observed. However, a previous investigation by Slade and colleagues found that older subjects undergoing third molar extractions were more likely to report oral impacts with the highest prevalence of oral impacts in the 25 years or older group (16).

Strengths and limitations

There are, however, several limitations of our study. First, prevalence of oral impacts might be related to variables not measured in this study. For example, we did not measure clinical characteristics at the patient level that have been shown to be associated with OHRQoL (39–40). In addition, the number of teeth, location of any missing teeth, teeth for which the patient is being treated, and/or clinical symptoms of the dental conditions were not included in the analyses. Patient’s self-reported sensitivities to various stimuli are collected at baseline for all four studies, and ongoing research is examining the relationship between hypersensitivity and OHRQoL. Also, it is likely that some of the patients had dental insurance which may create a sampling bias and differential utilization patterns than among people seeking care at public dental facilities. In terms of data analysis limitations, factors to consider are the number of multiple comparisons involved, the rarity of impacts since the vast majority of patients reported no oral health impact, and the cutoffs for low and high impacts were determined a priori but may not be clinically meaningful. The correlation of OHIP scores within patients participating in multiple protocols was not accounted for since they only account for 44 observations out of 2432. Ongoing work is focused on development and implementation of sophisticated statistical methods to handle the large number of patients reporting no oral health impact and potentially increasing the power to detect associations with covariates.

Implications

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to an area where research is lacking—namely, subjective OHRQoL among participants in a dental PBRN. More work is needed to elucidate the factors associated with the severity of oral impacts in this sample according to their protocol participation. The ordinal multidimensional statistical approach used in this study revealed that after controlling for protocol, presence in the high impact group was predominant among vulnerable groups, which is consistent with the literature (38,41). The information gained in this study can help dental practitioners to focus on the OHRQoL needs of certain groups, such as females and African Americans. Finally, this study encourages the assessment of patient-reported outcomes in the practice-based setting. The practice-based setting of the present study compared to the previous academic and international investigations increases the generalizability of these data to general dentists in the US.

In conclusion, the present study extends the work on OHRQoL in the dental PBRN setting and provides a rationale to assess PROs across various conditions in routine dental practice. No previously indexed studies have been found using the OHIP-14 to assess OHRQoL impact of individuals experiencing deep caries-related post-operative hypersensitivity or loss of tooth vitality and its consequences. The assessment of OHRQoL in routine dental practice can increase dental practitioners’ awareness of the impact of dental conditions from the patients’ perspective (e.g., psychological and physical well-being). Knowledge and awareness from such patient-oriented assessments could help dental practitioners identify those who express greater treatment needs and potentially modify their treatment plans. OHRQoL studies in the context of dental PBRNs are needed to assess the long-term impact of dental treatment and augment evidence-based care.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by a grant by the National Institute on Dental and Craniofacial Health (NIDCR) grant number # U01-DE016755. The authors thank the patients who volunteered to provide data for these analyses, and all the PEARL Practitioner-Investigators and their clinic staff. The authors also thank the PEARL data management and clinical coordinating team for their support, as well as Hongyu Wu for her assistance with statistical programming.

Contributor Information

Dr. Maria T. Botello-Harbaum, Outreach Manager for the EMMES Corporation.

Dr. Abigail G. Matthews, Statistician for the EMMES Corporation and Protocol Statistician for this study.

Mr. Damon Collie, PEARL Project Manager at the EMMES Corporation.

Mr. Donald A. Vena, Statistician for the EMMES Corporation and Principal Investigator for the PEARL Network Coordinating Center.

Dr. Ronald G. Craig, Department of Basic Sciences and Craniofacial Biology and Department of Periodontology and Implant Dentistry, and Director of the Information Dissemination Core, PEARL Network, New York University College of Dentistry.

Dr. Frederick A. Curro, PEARL Network Director of Recruitment, Retention and Operations, Clinical Professor Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology and Medicine, New York University College of Dentistry.

Dr. Van P. Thompson, PEARL Network Director of Protocol Development and Training, Professor; Chairperson Biomaterials, New York University College of Dentistry.

Dr. Hillary L. Broder, Department of Cariology and Comprehensive Care, New York University College of Dentistry.

The PEARL Network, Bluestone Center for Clinical Research, New York University College of Dentistry.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). Food and Drug Administration. Patient Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Rockville; MD: 2009. Guidance for Industry. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karasneh J, Al-Omir M, Al-Hamad KQ, Al Quran FA. Relationship between patients’ oral health-related quality of life, satisfaction with dentition, and personality profiles. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2009;10(6):E049–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related Quality of Life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locker D. Subjective oral health status indicators. In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, Dental Ecology; 1997. pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sischo L, Broder HL. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life: What, Why, How and Future Implications. J Dent Res. 2011;90(11):1264–70. doi: 10.1177/0022034511399918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shamrany MA. Oral health-related quality of life: a broader perspective. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2006;12 (6):804–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter MH, Woronuk JI, Tan HK, Lenz U, Koch R, Boening KW, et al. Oral Health Related Quality of Life and its association with sociodemographic and clinical findings in 3 northern outreach clinics. JCDA. 2007;73(2):153–153e. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel RR, Richards PS, Inglehart MR. Periodontal health, quality of life, and smiling patterns: An exploration. J Periodontol. 2008;79(2):224–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade GD. The oral health impact profile. In: Slade G, editor. Measuring Oral Health and Quality of Life. University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill: 1997. pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broder HL. Children’s oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35 (Suppl 1):5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlow N, Phillips C, Broder HL. Concurrent validity of the COHIP. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35 (Suppl 1):41–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders AE, Slade GD, Lim S, Reisine ST. Impact of oral disease on quality of life in the US and Australian populations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(2):171–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjakkes G, Jan-Jaap R, Tanvergert EM, Stegenga B. TMD pain: the effect on health related quality of life and the influence of pain duration. Health and Quality of Life outcomes. 2010;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekes K, John MT, Schaller HG, Hirsch C. Oral health-related quality of life in patients seeking care for dentin hypersensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36(1):45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schierz O, John MT, Reibmmann D, Mehrstedt M, Szentpétery A. Comparison of perceived oral health in patients with temporomandibular disorders and dental anxiety using oral health-related quality of life profile. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:857–866. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slade GD, Foy SP, Shugars DA, Phillips C, White RP., Jr The impact of third molar symptoms, pain, and swelling on oral health-related quality of life. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(9):1118–24. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagliardi DI, Slade GD, Sanders AE. Impact of dental care on oral health-related quality of life and treatment goals among elderly adults. Aust Dent J. 2008;53(1):26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montero-Martín J, Bravo-Perez M, Albaladejo-Martínez A, Hernández-Martin LA, Rosel-Gallardo EM. Validation the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14sp) for adults in Spain. Med Oral Patol Or Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14(1):E44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steele JG, Sanders AE, Slade GD, Allen PF, Lahti S, Nuttall N, et al. How do age and tooth loss affect oral health impacts and quality of life? A study comparing two national samples. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(2):107–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0301-5661.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacEntee MI, Hole R, Stolar E. The significance of the mouth in old age. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(9):1449–58. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gift HC, Redford M. Oral health and the quality of life. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8(3):673–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slade GD, Sanders AE. The paradox of better subjective oral health in older age. J Dent Res. 2011;90(11):1279–1285. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE, Persson GR, Yamaguchi DK, MacEntee MI, Wyatt CC. Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(4):137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders AE. Latino advantage in oral health-related quality of life is modified by nativity status. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):205–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.USDHHS. 2000, US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2000. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General - Executive Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGrath C, Bedi R. Gender variations in the social impact of oral health. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2000;46(3):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGrath C, Bedi R. Measuring the impact of oral health on quality of life in Britain using OHQoL-UK(W) J Public Health. 2003;63(2):73–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yiengprugsawan V, Somkotra T, Seubsman S, Sleigh AC The Thai Cohort Study Team. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among a large national cohort of 87,134 Thai adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9:42–50. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D, Swift CG, et al. The impact of educational level on oral health-related quality of life in older people in London. Eur J Oreal Sci. 2009;117:286–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spencer AJ, Harford J. Dental visiting among the Australian adult dentate population. Aust Dent J. 2007;52(4):336–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGrath C, Newsome PR. Patient-centered measures in dental practice: 2. Quality of Life Dent Update. 2007;34(1):41–2. doi: 10.12968/denu.2007.34.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nanda U, Andresen EM. Health-Related Quality of Life. Evaluation & the health professions. 1998;21(2):179–215. doi: 10.1177/016327879802100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeNucci DJ. the CONDOR Dental Practice-Based Research Networks. Dental Practice-Based Research Networks. In: Giannobile WV, Burt BA, Genco RJ, editors. Clinical Research in Oral Health. MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary Care Practice-Based Research Networks: Working at the Interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(Suppl 1):S12–S20. doi: 10.1370/afm.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shugars DA, Gentile MA, Ahmad N, Stavropoulos MF, Slade GD, Phillips C, et al. Assessment of oral health-related quality of life before and after third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(12):1721–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders AE, Slade GD, Turrell G, Spencer JA, Marcenes W. The shape of the socioeconomic-oral health gradient: implications for theoretical explanations. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(4):310–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slade GD, Nuttall N, Sanders AE, Steele JG, Allen PF, Lahti S. Impacts of oral disorders in the United Kingdom and Australia. Br Dent J. 2005;198(8):489–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunt RJ, Slade GD, Strauss RP. Differences between racial groups in the impact of oral disorders among older adults in North Carolina. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55(4):205–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerritsen A, Allen P, Witter D, Bronkhorst E, Creugers N. Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):126. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steele JG, Sanders AE, Slade GD, Allen PF, Lahti S, Nuttall N, Spencer AJ. How do age and tooth loss affect oral health impacts and quality of life? A study comparing two national samples. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32(2):107–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0301-5661.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed R, Broder HL, Jenkins G, Spivack E, Janal MN. Oral health promotion among older persons and their care providers in a nursing home facility. Gerodontology. 2006;23(2):73–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2006.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]