Abstract

Adherence counseling can improve antiretroviral adherence and related health outcomes in HIV-infected individuals. However, little is known about how much counseling is necessary to achieve clinically significant effects. We investigated antiretroviral adherence and HIV viral load relative to the number of hours of adherence counseling received by 60 HIV-infected drug users participating in a trial of directly observed antiretroviral therapy delivered in methadone clinics. Our adherence counseling intervention combined motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral counseling, was designed to include six 30 minute individual counseling sessions with unlimited “booster” sessions, and was offered to all participants in the parent trial. We found that, among those who participated in adherence counseling, dose of counseling had a significant positive relationship with antiretroviral adherence measured after the conclusion of counseling. Specifically, a linear mixed-effects model revealed that each additional hour of counseling was significantly associated with a 20% increase in post-counseling adherence. However, the number of cumulative adherence counseling hours was not significantly associated with HIV viral load, also measured after the conclusion of counseling. Our findings suggest that more intensive adherence counseling interventions may have a greater impact on antiretroviral adherence than less intensive interventions; however, it remains unknown how much counseling is required to impact HIV viral load.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy has the potential to prolong life expectancy, but requires high level of adherence (Paterson et al., 2000). Because factors that may adversely affect adherence, including poverty, depression, low educational level and active drug use, are prevalent among HIV-infected drug users, they may not receive full benefits from antiretroviral therapy (Arnsten et al., 2002; Carballo et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2004; Sharpe, Lee, Nakashima, Elam-Evans, & Fleming, 2004; Tucker et al., 2004). Adherence interventions, including peer mentoring, group support, directly observed therapy, cognitive-behavioral counseling, motivational interviewing, contingency management and education, have been shown to be effective for improving adherence and decreasing viral load (Simoni, Pearson, Pantalone, Marks, & Crepaz, 2006). However, it is unknown how much intervention is necessary to achieve significant effects. Because many HIV care settings have limited resources, knowledge about the amount of intervention necessary to improve behavioral and health outcomes may inform the design of optimal adherence interventions.

A few studies have investigated antiretroviral adherence interventions among drug users specifically (Sorensen et al., 1998; Williams et al., 2006). One found that, over 12 weeks, contingency management plus biweekly medication “coaching sessions” resulted in significantly better antiretroviral adherence than biweekly medication “coaching sessions” alone (Sorensen et al., 2007). Williams et al. (2006) found that, among current and former drug users, an educational intervention including 24 home visits over one year was associated with significantly better adherence and viral load than standard care. Another study found that three months after enrolling in a six session intervention including motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral counseling plus unlimited booster sessions, viral load significantly decreased among methadone maintained drug users (Cunningham et al., 2011). Also, studies have shown that directly observed therapy interventions for antiretroviral medications are effective for improving medication adherence and viral load among HIV-infected drug users (Altice et al., 2004; Behforouz et al., 2004; Berg, Litwin, Li, Heo, & Arnsten, 2010; Lanzafame, Trevenzoli, Cattelan, Rovere, & Parrinello, 2000; Mitty, Stone, Sands, Macalino, & Flanigan, 2002). However, none of these studies investigated how much intervention was required for significant changes in adherence or viral load to occur.

In addition, little is currently known about the precise dose of adherence counseling necessary to achieve clinical significance. One study compared 6 sessions to 12 sessions of an individual counseling intervention to enhance readiness for adherence among HIV-infected adults who previously failed antiretroviral treatment. Fifty percent of the study participants became adherent to their medications and achieved an undetectable viral load, with no differences between those who received 6 sessions and those who received 12 (Enriquez, Cheng, McKinsey, & Stanford, 2009). We know of no other study that has evaluated the dose of an antiretroviral adherence counseling intervention. To design the most effective adherence interventions, more research is needed to determine optimal intervention dosing. We therefore evaluated associations between adherence counseling intervention dose and both antiretroviral adherence and viral load among HIV-infected, methadone-maintained drug users.

Methods

Adherence Counseling Intervention

We developed the Support for Treatment Adherence Readiness (STAR) Program, an intervention based on the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model of Behavior Change (Cooperman, Parsons, Chabon, Berg, & Arnsten, 2007). The intervention combined motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral counseling to improve antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected drug users receiving treatment at a methadone maintenance clinic network in the Bronx, New York. The semi-structured adherence intervention was provided by paraprofessional counselors and consisted of six 30-minute sessions. Adherence counselors worked to identify gaps in information, motivation, and behavioral skills as well as unaddressed mental health, substance abuse, financial, vocational, and housing issues that might impede HIV medication adherence. After the initial sessions, patients could obtain unlimited “booster sessions.” Fidelity to the intervention was assured by audio taping sessions and feedback during weekly supervision with a licensed psychologist.

Intervention Participants

The STAR Program was offered to all HIV-infected patients in a network of twelve methadone maintenance clinics in the Bronx, New York. However, for the current study we limited our analyses to subjects participating in the Support for Treatment Adherence Research Through Directly Observed Therapy (STAR*DOT) trial, since trial participants had antiretroviral adherence and viral load measured at multiple standard time points. STAR*DOT was a randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of directly observed antiretroviral therapy provided on-site at a methadone clinic during a 24-week intervention period (Berg et al., 2009). After the 24 week intervention period, STAR*DOT participants were followed for a 12 month post-intervention period. We included in this analysis all STAR*DOT participants for whom adherence and viral load were measured at any point during the 12 month post-intervention period (N=60), including those who did and did not receive adherence counseling. STAR*DOT post-intervention assessments were used to measure the impact of counseling on adherence and viral load, after the adherence counseling period concluded.

STAR*DOT and its outcomes have been previously described (Berg et al., 2010; Berg, Litwin, Li, Heo, & Arnsten, 2011; Berg et al., 2009). Potential participants were eligible for inclusion if they were: 1) HIV-infected, 2) prescribed antiretroviral therapy, 3) receiving HIV medical care at their methadone clinic or a closely affiliated site, 4) attending the methadone clinic 5 or 6 days per week, 5) on a stable dose of methadone for two weeks, and 6) genotypically sensitive to their prescribed antiretroviral regimen.

Participants in the STAR*DOT trial were randomized to receive antiretroviral DOT for 24 weeks (DOT), or to self-administer their medications (treatment as usual, TAU). Participants randomized to DOT received one dose of their antiretroviral medications at the same time as their daily methadone dose. Non-observed evening and weekend doses were provided to DOT participants in individual take-home pill boxes. After the initial 24 week intervention period, participants randomized to DOT self-administered their medications.

Participants randomized to TAU self-administered their antiretroviral medications during both the 24 week STAR*DOT intervention period and the 12 month post-intervention period. Adherence counselors met with all STAR*DOT participants not already engaged in the STAR Program to introduce the adherence counseling program and attempt to engage them in the adherence counseling intervention.

Though the STAR*DOT trial demonstrated that participants randomized to DOT had significantly greater adherence and lower HIV viral loads than participants randomized to TAU immediately after the 24 week intervention period (Berg et al., 2010; Brust et al., 2010), we have also noted that the significant effects of the STAR*DOT intervention attenuated rapidly after the 24-week intervention ended (Berg, et al., 2011). Because our goal for the present study was to determine the impact of counseling dose on adherence and HIV viral load among participants in both arms of the trial after the adherence counseling period concluded, we limited our outcome measures for the current analysis to adherence and HIV viral load during the STAR*DOT post-intervention period, and also adjusted for the effect of DOT in all analyses.

Research Visits During the STAR*DOT Trial

For all STAR*DOT participants, research visits occurred at baseline, weekly for the first 8 weeks, and monthly thereafter. Surveys were administered using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview technology (Metzger et al., 2000). Blood for quantifying HIV viral load was drawn by research assistants at 8 points during the trial.

Measures: Independent Variables

Demographic and clinical characteristics

At the STAR*DOT baseline visit, we assessed age, gender, marital status, race, education, income, education, drug use, and HIV clinical characteristics.

Dose of adherence counseling

Because the length of counseling sessions varied, our independent variable was number of counseling hours, rather than number of counseling sessions. To capture this, adherence counselors recorded the date and length of each adherence counseling session. To ensure a standardized measure of counseling dose, we defined a 15 month counseling period for each participant, including 6 months prior to STAR*DOT, 24 weeks (6 months) during the STAR*DOT intervention, and three months following STAR*DOT. We then calculated total number of adherence counseling hours for each participant, including all counseling sessions conducted during the 15 month counseling period. Although some participants had counseling prior to the defined 15 month counseling period, we did not include these sessions because their timing was highly variable (from weeks to years prior to STAR*DOT).

Measures: Dependent Variables

Antiretroviral adherence

Our major outcome was antiretroviral adherence following the standardized counseling period. To assess this, we included three measures of adherence obtained 3, 6, and 9 months after the 15 month counseling period. To quantify adherence, we used both Medication Event Monitoring Systems (MEMS) and pill counts. During the STAR*DOT post-intervention, when all participants self-administered their medications, we electronically monitored the backbone of the antiretroviral regimen (usually a protease inhibitor or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor) using MEMS, and conducted pill counts for the remainder of the medications. We then created a composite adherence measure for each participant by computing a weighted average of MEMS and pill count adherence rates at each visit. Missing data, due to lost follow-up or any other reason, were not included in the calculation of adherence.

Viral load

We also assessed HIV viral load following the standardized counseling period. We included three measures of viral load obtained 3, 6, and 9 months after the 15 month counseling period. Plasma viral load was quantified using the VERSANT HIV-1 bDNA 3.0 assay (Bayer, Tarrytown, NY).

Statistical Analyses

For descriptive statistics, categorical variables were summarized as percents and continuous variables were summarized using means and medians. We then used chi-square, Mann-Whitney U, or t-tests to compare variables between participants who did and did not participate in any adherence counseling during the 15 month counseling period.

To test the effect of cumulative counseling hours during the 15 month counseling period on the repeatedly measured adherence rates and viral loads following counseling, we applied two sets of mixed effects linear models. First, to all subjects regardless of experience of counseling, and second, only to those subjects who received counseling during the 15 month counseling period. To adjust for STAR*DOT intervention effects, we included the 24 week (immediate post STAR*DOT intervention) adherence rate or viral load in the appropriate model. The within-subject correlation of adherence rate and viral load was assumed to be unstructured.

Results

Participant Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=60)

| All N=60 |

No adherence counseling during counseling period n=38 |

Any adherence counseling during counseling period n=22 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea, mean (sd) | 48 (7) | 49 (6)* | 45 (7)* |

| Gendera, (%) | |||

| Male | 50 | 53 | 46 |

| Racea, (%) | |||

| White | 12 | 13 | 9 |

| Black | 42 | 42 | 41 |

| Other | 47 | 45 | 50 |

| Ethnicitya, (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 45 | 42 | 50 |

| Educationa, (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 12 | 11 | 14 |

| High school (partial or completed) | 63 | 61 | 68 |

| College (partial or completed) | 25 | 29 | 18 |

| Marital statusa, (%) | |||

| Married / living with partner | 45 | 45 | 46 |

| Widowed / separated / divorced | 28 | 26 | 32 |

| Single | 27 | 29 | 23 |

| Employmenta, (%) | |||

| Employed | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Unable to work / unemployed / other | 97 | 100 | 91 |

| Years of methadone maintenancea, median (IQR) |

11 (5-17) | 8 (5-20) | 11 (7-15) |

| Years living with HIVa, median (IQR) | 13 (9-17) | 15 (9-19) | 12 (9-13) |

| Antiretroviral adherenceb,c, mean (sd) | .72 (.29) | .78 (.24)* | .61 (.35)* |

| Viral loadb (log10 copies/ ml), mean (sd) | 2.51 (1.03) | 2.24 (.79)* | 2.96 (1.21)* |

| Absolute CD4+ T cell countb, cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 367 (192-512) | 416 (212-598)* | 253 (140-347)* |

Measured at STAR*DOT enrollment.

Measured at conclusion of STAR*DOT 24 week intervention. These data are described because they are included in the linear models to control for STAR*DOT intervention effects.

Measured by pill count only.

p≤.05 for the comparison of those with no vs. any adherence counseling.

Participants’ mean age was 48 years. Half were male, most were Black (42%) or Hispanic (45%), and 45% were married or living with a partner. Sixty-three percent had attended or completed high school, yet almost all were unemployed (97%). Participants were on methadone maintenance for a median of 11 years, and had been living with HIV for a median of 13 years.

Factors Associated with Adherence Counseling

Thirty-seven percent of participants (n=22) received any adherence counseling during the counseling period. Those who received counseling were younger (45 v. 49 years, p≤.05) and had lower CD4 counts (253 v 416 cells/mm3, p≤.05) than those who did not receive counseling. In addition, immediately after the STAR*DOT intervention period (at week 24), those who received counseling had lower adherence (61% v. 78%, p ≤ 0.05) and higher viral load (2.96 v. 2.24 log10 copies/ml, p≤0.05) than those who did not receive counseling.

Among the 22 participants who received counseling, 36% received ≤1 hour of counseling, 41% received 1-2 hours, and 23% received 2-3 hours of counseling. Forty-five per cent of the 22 participants completed the entire STAR intervention, and 41% had at least one booster session. Counseling sessions were equally distributed throughout the 15 month counseling period.

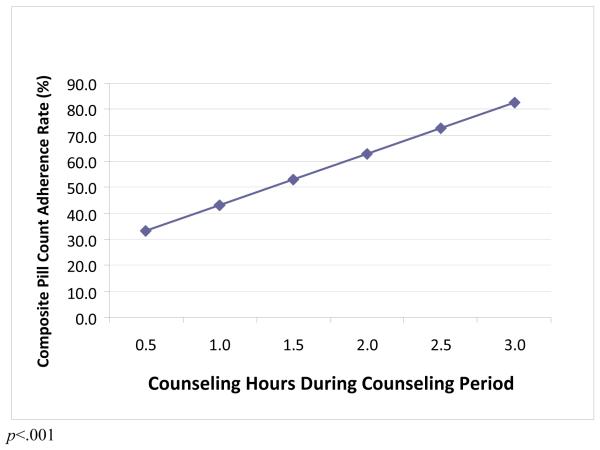

Relationship between Adherence Counseling Dose and Antiretroviral Adherence (Figure)

Figure 1.

Association between post-counseling adherence and counseling dose (adjusted for immediate post STAR*DOT intervention effects; n=22)

Among participants who received counseling, we observed a significant relationship between cumulative adherence counseling hours and antiretroviral adherence (measured following counseling). Specifically, each additional hour of counseling was associated with a 20% increase in adherence rate. The relationship between adherence counseling dose and antiretroviral adherence was not significant when all participants (including those who did not receive counseling) were included.

Relationship between Adherence Counseling Dose and HIV Viral Load

We did not observe a significant association between cumulative adherence counseling hours and post-counseling HIV viral load, either when all participants were included in the analysis, or when only those who received any adherence counseling were included.

Discussion

In this sample of HIV-infected methadone maintained drug users participating in a trial of directly observed antiretroviral therapy, we found that counseling dose had a significant positive relationship with antiretroviral adherence measured after counseling. However, we did not observe a significant association between adherence counseling dose and post-counseling viral load. These results suggest that, while larger doses of an adherence counseling intervention are associated with improved antiretroviral adherence as compared to lower doses, even more intensive adherence counseling may be necessary to improve adherence enough to significantly impact HIV viral load.

While participants who received adherence counseling were mostly equivalent to participants who did not receive counseling, there were some differences. Those that received counseling were younger; perhaps, younger participants had less knowledge of antiretroviral treatment, and felt a greater need for HIV-related education and support. This finding suggests that interventions targeting younger HIV-infected individuals may have greater participation. Also, those that received counseling had significantly lower antiretroviral adherence, higher HIV viral loads, and lower CD4 counts than those that did not receive any counseling. It may be that persons who were managing their HIV effectively did not feel the need for counseling as acutely as those who were not managing their HIV well, but further research is needed to better understand these relationships.

We found a significant positive relationship between adherence counseling dose and antiretroviral adherence; however, the relationship between number of hours of adherence counseling received and viral load was not significant. Possibly, those who were more committed to antiretroviral adherence or already had higher levels of adherence were more likely to attend more adherence counseling. Alternatively, the intervention may have helped to address gaps in information, motivation, and behavioral skills necessary for adherence, however not to the extent required for viral load suppression. While we observed that greater adherence counseling time was associated with greater adherence, our participants received a maximum dose of three hours of counseling (the equivalent to approximately six sessions of adherence counseling), and maximum adherence was only 85%. Since over 90% of participants in the STAR*DOT study were taking protease inhibitor containing regimens and only one quarter were taking non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors containing regimens, 95% adherence was likely necessary for an optimal viralogic outcome (Paterson et al., 2000). Possibly, greater than three hours of adherence counseling (or more than six 30 minute adherence counseling sessions) would be associated with greater improvements in information, motivation, and behavioral skills, higher antiretroviral adherence rates and, consequently, decreased viral loads. The results of this study suggest that more intensive adherence counseling interventions may have the most benefit for improved antiretroviral adherence in a drug using population; however, further research is needed to determine the amount of adherence counseling necessary to have an impact on biological outcomes and causal relationships.

We found that, among those who received counseling, 36% completed ≤1 hour of counseling (the equivalent of one or two sessions). The amount of adherence counseling received by those who chose to participate is consistent with previous psychotherapy studies in HIV-infected populations. Studies investigating engagement in mental health care and psychotherapy among HIV-infected patients found that approximately 30% of patients drop out of treatment after one session (Bottonari & Stepleman, 2009; Reece, 2003). In these studies, factors associated with counseling retention among patients infected with HIV have included: social support, previous psychotherapy, treatment with pharmacotherapy, diagnosis of a personality disorder, having an ethnic minority provider, perceived barriers to treatment, level of HIV related stigma, ethnicity, and CD4 count (Bottonari & Stepleman, 2009; Reece, 2003). Many of these factors are also likely to impact engagement in adherence counseling, and should be considered in the design of adherence interventions to maximize treatment engagement.

No known studies have investigated the impact of adherence counseling dose in HIV-infected drug users; however, there is a body of research on the dose-effect of psychotherapy in various populations, including a few studies in drug users and those with HIV. These studies have had conflicting results (Covi, Hess, Schroeder, & Preston, 2002; Ghebremichael, Hansen, Zhang, & Sikkema, 2006). For example, Covi et al. evaluated the dose response of cognitive behavioral therapy in 68 cocaine abusers randomly assigned to twice weekly, once weekly, or biweekly sessions over a 12 week period (Covi, et al., 2002). The researchers found no differences in retention, reduction in drug use, or reduction in psychiatric distress between the groups, suggesting that a smaller treatment dose is equally as effective as a larger dose. In contrast, another study investigated the dose-effect of a group intervention for bereaved persons with HIV, and found that, over time, psychiatric distress and grief decreased longitudinally in relationship to intervention dose (Ghebremichael, et al., 2006).

Despite its strengths, our study has some limitations. First, since participants were not randomized to receive different doses of adherence counseling, we are unable to determine cause-effect relationships. Second, this study included only HIV-infected, methadone maintained drug users who chose to participate in a clinical trial of directly observed therapy. Therefore, these findings may not generalize to individuals not in methadone maintenance treatment or participating in a clinical trial for DOT. Finally, this study was conducted on a relatively small number of individuals. Perhaps a study with a larger sample could better detect the relationship between adherence counseling dose, antiretroviral adherence, and viral load.

In conclusion, this study provides important information that can be useful for designing adherence counseling interventions and future studies. Our findings suggest that more intensive adherence counseling interventions are likely to have a greater impact on antiretroviral adherence than less intensive interventions. Further, greater than three hours of counseling may be needed to increase antiretroviral adherence to the point that it has an impact on decreasing viral load. Therefore, interventions that address treatment retention may be most effective. While our study suggests that larger doses of antiretroviral adherence counseling are likely more beneficial than smaller doses, more research on adherence counseling engagement and retention is necessary to design optimal adherence counseling interventions for HIV-infected individuals to receive maximum benefits.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01DA015302 and K23DA025049 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Grant 13-1624225 from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute, and a Center for AIDS Research Grant P30AI51519 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The authors thank Terri Febbrarro, Mark Flores, Ken Harris, Wendy Hunt, Angela Jeffers, Daniel Kaswan, Marc King, Lisa Moseley, Rosie Rodriguez, and Edwin Roman for coordinating and providing the adherence counseling. The authors thank Metta Cantlo, Amanda Carter, Hillel Cohen, Elise Duggan, Uri Goldberg, Harris Goldstein, Joseph Hecht, Laxmi Modali, Jennifer Mouriz, Francesca Parker, Megha Ramaswamy, and Maite Villanueva for assistance with protocol development, pharmacy coordination, data collection and management, and laboratory analyses. This study was dependent on the cooperation of the medical providers, nurses, and patients at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center Division of Substance Abuse. We also thank the staff members at Melrose Pharmacy, Bendiner & Schlesinger, Inc., and Bio-Reference laboratories, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Altice FL, Mezger JA, Hodges J, Bruce RD, Marinovich A, Walton M, et al. Developing a directly administered antiretroviral therapy intervention for HIV-infected drug users: implications for program replication. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 5):S376–387. doi: 10.1086/421400. doi: 10.1086/421400 CID33205 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):377–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. doi: jgi10644 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behforouz HL, Kalmus A, Scherz CS, Kahn JS, Kadakia MB, Farmer PE. Directly observed therapy for HIV antiretroviral therapy in an urban US setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(1):642–645. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200405010-00016. doi: 00126334-200405010-00016 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Litwin A, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy improves adherence and viral load in drug users attending methadone maintenance clinics: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.025. doi: S0376-8716(10)00288-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Litwin AH, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Lack of sustained improvement in adherence or viral load following a directly observed antiretroviral therapy intervention. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):936–943. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir537. doi: cir537 [pii] 10.1093/cid/cir537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Mouriz J, Li X, Duggan E, Goldberg U, Arnsten JH. Rationale, design, and sample characteristics of a randomized controlled trial of directly observed antiretroviral therapy delivered in methadone clinics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(5):481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.05.003. doi: S1551-7144(09)00102-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.cct.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottonari KA, Stepleman LM. Factors associated with psychotherapy longevity among HIV-positive patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(2):109–118. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0081. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0081 10.1089/apc.2008.0081 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brust JC, Litwin AH, Berg KM, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Directly Observed Antiretroviral Therapy in Substance Abusers Receiving Methadone Maintenance Therapy Does Not Cause Increased Drug Resistance. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0181. doi: 10.1089/AID.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo E, Cadarso-Suarez CCI, Fraga J, Ocampo A, Ojea R, Prieto A. Assessing relationships between health-related quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13:587–599. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021315.93360.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman NA, Parsons JP, Chabon B, Berg KM, Arnsten JH. The development and feasibility of an intervention to improve antiretroviral adherence among HIV-positive patients receiving primary-care in methadone clinics. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. 2007;6(1/2):101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Covi L, Hess JM, Schroeder JR, Preston KL. A dose response study of cognitive behavioral therapy in cocaine abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23(3):191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00247-7. doi: S0740547202002477 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Cooperman NA, Berg KM, Litwin AH, Arnsten JH. Strategies to improve access to and utilization of health care services and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(2-3):218–232. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.522840. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.522840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez M, Cheng AL, McKinsey DS, Stanford J. Development and efficacy of an intervention to enhance readiness for adherence among adults who had previously failed HIV treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(3):177–184. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebremichael MS, Hansen NB, Zhang H, Sikkema KJ. The dose effect of a group intervention for bereaved HIV-positive individuals. Group Dynamics. 2006;10(3):167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzafame M, Trevenzoli M, Cattelan AM, Rovere P, Parrinello A. Directly observed therapy in HIV therapy: A realistic perspective? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(2):200–201. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner C, Navaline H, Valenti F, Holte S, et al. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitty JA, Stone VE, Sands M, Macalino G, Flanigan T. Directly observed therapy for the treatment of people with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a work in progress. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(7):984–990. doi: 10.1086/339447. doi: CID011343 [pii] 10.1086/339447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. doi: 200007040-00004 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece M. HIV-related mental health care: factors influencing dropout among low-income, HIV-positive individuals. AIDS Care. 2003;15(5):707–716. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001595195. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001595195 M3H3CRETN3CJVMQ9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, et al. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(2):141–150. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb 486486 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe TT, Lee LM, Nakashima AK, Elam-Evans LD, Fleming PL. Crack cocaine use and adherence to antiretroviral treatment among HIV-infected black women. J Community Health. 2004;29(2):117–127. doi: 10.1023/b:johe.0000016716.99847.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Marks G, Crepaz N. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S23–35. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248342.05438.52 00126334-200612011-00005 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, Gruber V, Kletter E, Batki SL, et al. Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. doi: S0376-8716(06)00363-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Mascovich A, Wall TL, DePhilippis D, Batki SL, Chesney M. Medication adherence strategies for drug abusers with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):297–312. doi: 10.1080/713612419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Orlando M, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Psychosocial mediators of antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive adults with substance use and mental health problems. Health Psychol. 2004;23(4):363–370. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.363 2004-16161-004 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AB, Fennie KP, Bova CA, Burgess JD, Danvers KA, Dieckhaus KD. Home visits to improve adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(3):314–321. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221681.60187.88. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221681.60187.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]