Abstract

This chapter will focus on the role of microRNAs (miRs) in regulating the actions of opioid drugs through the opioid receptors. Opioids, such as morphine, are analgesics that are used for treating many forms of acute and chronic pain. However, their chronic use is limited by undesirable effects such as opioid tolerance. The μ opioid receptor (MOR) is the primary receptor responsible for opioids’ analgesia and antinociceptive tolerance. The long 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of MOR mRNA is of great interest since this region may contain elements for the post-transcriptional regulation of receptor expression, such as altering the stability of mRNA, influencing translational efficiency, and controlling mRNA transport. MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules that exert their functions through base-pairing with partially complementary sequences in the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs, resulting in decreased polypeptide formation from those mRNAs. Since the discovery of the first miR, lin-4 in Caenorhabditis elegans, hundreds of miRs have been identified from humans to viruses, which have provided a crucial and pervasive layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation. The nervous system is a rich source of miR expression, with a diversity of miR functions in fundamental neurobiological processes including neuronal development, plasticity, metabolism, and apoptosis. Recently, the let-7 family of miRs is found to be a critical regulator of MOR function in opioid tolerance. Let-7 is the first identified human miR. Its family members are highly conserved across species in sequence and function. In the review, we will present a brief review of the opioid receptors, their regulation, and opioid tolerance as well as an overview of miRs and a perspective how miRs may interact with MOR and serve as a regulator of opioid tolerance.

Keywords: opioid, miR, epigenetics, addiction, pain

Introduction

Since first isolated from opium poppy in the early nineteenth century, morphine and related opioids remain as the most powerful analgesics to treat many forms of acute and chronic pain. However, repeated and prolonged use of opioids leads to tolerance, of which, the analgesic tolerance is the most problematic that can lead to therapeutic failure (i.e., inadequate pain control; McQuay, 1999). In some cases, even the highest tolerable dose of an opioid cannot achieve the desirable analgesic effect in patients (Wang and Wang, 2006; Harden, 2008). Development of opioid tolerance not only limits the analgesic efficacy, but the increased doses of opioids in order to counter tolerance exacerbate another problem, namely opioid addiction that is a significant medical and public health problem. Extensive efforts have been made to elucidate the mechanisms underlying opioid tolerance and drug addiction (Kieffer and Evans, 2002). Increasing evidence implicates the contribution of transcriptional and epigenetic regulation in opioid tolerance and drug addiction, such as activation and inhibition of transcription factors (Carlezon et al., 2005; Zachariou et al., 2006), modification of chromatin and DNA structure (Renthal et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2011), and induction of non-coding RNAs including microRNAs (Pietrzykowski, 2011; Robison and Nestler, 2011).

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that repress target gene expression through base-pairing with partially complementary sequences in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of target mRNAs. Owing to recent cloning, sequencing, and computational efforts, the numbers of known miRs has been rapidly increasing, and to date, there are a total of 21,643 mature miRs found across 103 species, of which 1921 miRs are found in humans (miRBase Release 18.0, November 20111). With the emerging identification of miRs from humans to viruses, a crucial and pervasive layer of post-transcriptional gene regulation by miRs has been elucidated (Ambros, 2004; Taft et al., 2010). It is generally accepted that miRs serve as an important class of epigenetic regulators that participate in a variety of cellular activities. In respect to their diverse functions, miRs play an integral role in fundamental neurobiological processes including neuronal development, plasticity, metabolism, and apoptosis (Kosik, 2006). As one form of long-lasting synaptic plasticity, opioid tolerance is a particularly interesting research area to study miR-mediated cellular adaptation. In this review, we summarize recent findings on miRs in opioid tolerance, with a focus on the role of let-7 miRs in regulating opioid tolerance.

Mu Opioid Receptor and Opioid Tolerance

The μ opioid receptor (MOR), a member of the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily, is the primary receptor responsible for opioids’ analgesia and antinociceptive tolerance (Matthes et al., 1996; Sora et al., 1997). Opioid tolerance may be result from opioid receptor desensitization and trafficking, which include opioid receptor down-regulation, internalization, and uncoupling from G-proteins due to chronic exposure to opioid agonists (Bailey and Connor, 2005; Martini and Whistler, 2007; Koch and Hollt, 2008; Lopez-Gimenez and Milligan, 2010). Receptor down-regulation as one of mechanisms contributing to opioid tolerance has been previously proposed (Davis et al., 1979; Tao et al., 1987; Bhargava and Gulati, 1990; Bernstein and Welch, 1998; Diaz et al., 2000). Chronic morphine treatment produced a marked decrease in brain MOR density (Davis et al., 1979; Tempel et al., 1988). Down-regulation of the high-affinity MOR site in rats has also been reported following continuous infusion of morphine (i.t.; Wong et al., 1996) or etorphine (s.c.; Tao et al., 1987). Morphine-induced MOR down-regulation was also observed in SH-SY5Y cells, with or without differentiation (Zadina et al., 1993). In addition to receptor down-regulation, chronic treatment with morphine has been shown to significantly reduce MOR-signaling in sensory neurons and brainstem nuclei (Sim et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2006), which are in agreement with the findings that reduced receptor number and resultant reduced MOR-signaling contribute to opioid tolerance. On the other hand, there have been reports that MOR expression was not altered (Dum et al., 1979) or even up-regulated (Lewis et al., 1984) in the brain by various opioids. Some of the discrepancies may be caused by uncontrolled variables (e.g., different opioids, doses, methods of opioid treatments, anatomical regions, and times samples were taken, integrality of tissue samples before assays, and opioid receptor subtypes studied), as well as detection methods. It has been suggested that MOR down-regulation is agonist selective and depends on the agonist’s intrinsic efficacy (Nishino et al., 1990; Chakrabarti et al., 1997; Chan et al., 1997; Koch and Hollt, 2008). The purity and selectivity of radiolabeled ligands – a problem not only for some early studies, but also in more recent reports employing questionable materials – used in studies are the other potential culprits for conflicting findings.

Direct Interaction between Let-7 Family miRs and MOR

The long 3′-UTR of MOR mRNA (Ide et al., 2005; Han et al., 2006) suggests that this region may contain physiologically relevant elements for regulating receptor expression by mechanisms such as miR targeting. Indeed, early research on 3′-UTR of human MOR mRNA suggested that MOR expression was increased after a 712-bp segment, immediately downstream of the stop codon, was removed (Zollner et al., 2000). Comparative bioinformatics predicted potential miRs that may interact with the human and mouse MOR (Table 1). Let-7 family of miRs was identified as a top candidate according to the number of putative target sites and alignment pattern. Our group experimentally validated the in silico prediction that members of the let-7 miR family can interact with the 3′-UTR of MOR mRNA at the predicted positions (He et al., 2010). Furthermore, downregulating let-7 with specific LNA-modified antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (LNA-let-7-AS) was found to increase MOR expression in SH-SY5Y cells, a human neuroblastoma cell line, suggesting that (1) MOR is a target of let-7; (2) expression of MOR is under constitutive suppression by let-7.

Table 1.

MicroRNA targets predicted by miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/getGeneForm.do) and ranked according to the alignment scores.

| miRNA | Query target sites | Alignment score | PhastCons score |

|---|---|---|---|

| HUMAN OPRM1 3′-UTR | |||

| hsa-miR-600 | 291 | 169 | 0.666615 |

| hsa-miR-384 | 83 | 157 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-105 | 172 | 156 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-let-7b | 381 | 154 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-let-7c | 383 | 154 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-let-7g | 386 | 154 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-let-7i | 386 | 154 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-1272 | 261 | 154 | 0.643121 |

| hsa-miR-642 | 151 | 154 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-98 | 386 | 154 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-let-7f | 383 | 153 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-let-7d | 386 | 152 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 401 | 152 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-198 | 124 | 152 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-let-7a | 385 | 151 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-302a | 169 | 151 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-1324 | 286 | 150 | 0.666615 |

| hsa-miR-192 | 102 | 150 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-215 | 102 | 150 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-648 | 144 | 150 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-18b | 399 | 149 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-383 | 389 | 149 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-526b | 52 | 149 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-659 | 233 | 149 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-let-7e | 385 | 147 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-302b | 170 | 147 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-136 | 166 | 146 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-431 | 220 | 145 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-557 | 216 | 145 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-1262 | 105 | 144 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-154 | 322 | 144 | 0.666615 |

| hsa-miR-373 | 168 | 144 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-583 | 114 | 144 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-1259 | 271 | 143 | 0.643121 |

| hsa-miR-135a | 264 | 143 | 0.643121 |

| hsa-miR-135b | 264 | 143 | 0.643121 |

| hsa-miR-493 | 4 | 143 | 0.6910845 |

| hsa-miR-519c-5p | 79 | 143 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-520d-3p | 170 | 143 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-580 | 307 | 143 | 0.666615 |

| hsa-miR-196a | 382 | 142 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-520a-3p | 172 | 142 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-577 | 302 | 142 | 0.666615 |

| hsa-miR-142-3p | 384 | 141 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-378 | 208 | 141 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-422a | 207 | 141 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-1826 | 387 | 140 | 0.607749 |

| hsa-miR-302c | 170 | 140 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-302d | 170 | 140 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-504 | 1 | 140 | 0.6910845 |

| hsa-miR-521 | 89 | 140 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-9 | 234 | 140 | 0.619627 |

| hsa-miR-942 | 333 | 140 | 0.666615 |

| MOUSE OPRM1 3′-UTR | |||

| mmu-miR-540-5p | 278 | 168.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-540-3p | 395 | 159.0 | 0.584342 |

| mmu-miR-134 | 403 | 158.0 | 0.584342 |

| mmu-miR-302c | 165 | 158.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-302d | 165 | 151.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-let-7i | 384 | 149.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-139-5p | 363 | 149.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-let-7g | 388 | 148.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-199a-3p | 193 | 148.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-199b | 193 | 148.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-496 | 241 | 148.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-532-3p | 63 | 148.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-let-7a | 388 | 147.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-let-7f | 388 | 147.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-let-7c | 386 | 146.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-486 | 214 | 146.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-741 | 512 | 146.0 | 0.567263 |

| mmu-miR-383 | 93 | 144.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-695 | 404 | 144.0 | 0.584342 |

| mmu-let-7b | 388 | 143.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-let-7e | 388 | 143.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-188-3p | 64 | 143.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-196b | 386 | 143.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-302b | 165 | 143.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-323-5p | 233 | 143.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-466f-5p | 138 | 143.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-98 | 387 | 143.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-298 | 391 | 142.0 | 0.584342 |

| mmu-miR-339-3p | 71 | 142.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-381 | 528 | 142.0 | 0.590822 |

| mmu-miR-682 | 186 | 142.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-let-7d | 388 | 141.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-504 | 57 | 141.0 | 0.586054 |

| mmu-miR-154 | 321 | 140.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-196a | 387 | 140.0 | 0.62498 |

| mmu-miR-340-5p | 527 | 140.0 | 0.590822 |

| mmu-miR-34b-3p | 367 | 140.0 | 0.62498 |

In order to elucidate a physiological role of let-7 in regulating MOR and opioid tolerance, we further examined the in vivo relevance of let-7 miRs in cellular and animal models of opioid tolerance. For the former, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with morphine (1−10 μM for 24–48 h) to induce cellular tolerance. The expression of let-7 miRs was significantly up-regulated by chronic treatment with morphine, while the expression level of MOR was reduced as determined by the western blotting method (He et al., 2010) and the receptor radioligand binding using 3H-DAMGO (He and Wang, unpublished data). Therefore, chronic morphine treatment caused the increase of let-7 and decrease of MOR expression during the development of opioid tolerance in SH-SY5Y. Furthermore, the regulation of let-7 expression by morphine occurred in a mouse model of opioid tolerance. Mice were implanted s.c. with a 75-mg morphine pellet (75 mg morphine pellet/mouse, s.c.). Brain expression of let-7 increased gradually over time after morphine treatment, temporally correlating with the development of antinociceptive tolerance to morphine. Interestingly, up-regulation of let-7 occurred in MOR-expressing cells, but not in MOR-negative cells in mice brain cortex region as determined by in situ hybridization (He et al., 2010). This was in agreement with the aforementioned finding that MOR is a direct target of let-7. In order to further examine a causative role of let-7 in leading to opioid tolerance, we directly targeted let-7 in the mouse model of opioid tolerance. Treatment with the let-7 inhibitor (i.c.v.) decreased brain let-7 levels and partially attenuated opioid antinociceptive tolerance (He et al., 2010).

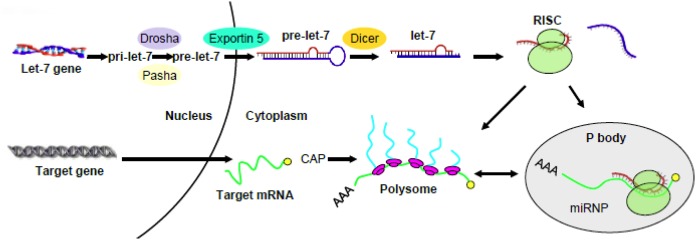

Previous reports from a number of different cell lines or animal models (e.g., Brodsky et al., 1995; Johnson et al., 2006) indicated that MOR mRNA was not changed upon treatment with morphine. We also found that the total MOR transcripts were unchanged by morphine. For example, MOR mRNA remained the same in SH-SY5Y cells following chronic morphine treatment. It raised a question as to how let-7 miRs repress MOR in opioid tolerance. We confirmed that let-7 did not affect MOR mRNA stability; however, polysome-bound MOR transcript was significantly decreased. Where is MOR mRNA hiding? It turns out that it can be accumulated in P-bodies. So these intriguing data led us to propose the following regulatory mechanism where upon let-7 can regulate opioid tolerance: let-7 recruits and sequesters MOR mRNA to P-bodies that are deprived of translational machinery, effectively reducing polysome-bound MOR mRNA and leading to translation repression. A similar pathway was observed in HEK293 and HeLa cells (Pillai et al., 2005), thus translation repression may serve as a general mechanism by let-7 to regulate its target gene expression (Figure 1). Keep in mind that let-7 activity is turned up in opioid tolerance by up-regulation of their transcripts. Nature works in a wonder to ensure the activity of let-7, ultimately dampening the activity of opioids upon persistent activation.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram proposing a mechanism for the regulation of target gene by let-7. Pri- and pre-let-7 are produced and exported into the cytosol where the mature let-7 was incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The latter recruits and sequesters target mRNA to P-bodies that are deprived of translational machinery, effectively reducing polysome-bound mRNA and leading to translation repression (modified from He et al., 2010).

Potential Target Genes of Let-7 in Opioid Tolerance

Let-7 was the first identified human miR. Its family members are highly conserved across species in sequence and function (Pasquinelli et al., 2000). Major roles of let-7 include the regulation of stem-cell differentiation, neuromuscular development, and cell proliferation & differentiation (Reinhart et al., 2000; Mansfield et al., 2004; Roush and Slack, 2008). Let-7 was initially identified as a heterochronic gene (Pasquinelli et al., 2000). In mammals, let-7 levels increase during embryogenesis and during brain development (Schulman et al., 2005; Wulczyn et al., 2007). Let-7 is undetectable in human and mouse embryonic stem cells, and the level of let-7 increases upon differentiation (Thomson et al., 2004, 2006; Wulczyn et al., 2007). This high expression of let-7 is then maintained in various adult tissues (Sempere et al., 2004; Thomson et al., 2004). Furthermore, let-7 is widely viewed as a tumor suppressor miR (Boyerinas et al., 2010). There is a clear link between loss of let-7 expression and the development of poorly differentiated, aggressive cancers (Takamizawa et al., 2004; Dahiya et al., 2008; Childs et al., 2009). Using the computational algorithm TargetScan 6.02 to screen human 3′-UTR sequences containing let-7 family miRs complementary sites, 886 conserved targets, with a total of 989 conserved sites and 111 poorly conserved sites were predicted. High-mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2), which is the top-scoring candidate gene on the list (Table 2), was confirmed as a direct let-7 target both in vitro and in vivo (Lee and Dutta, 2007; Mayr et al., 2007; Shell et al., 2007). HMGA2 is a chromatin-associated non-histone protein capable of modulating chromatin architecture and thus affecting transcription. In addition to abundant studies on HMGA2 in embryogenesis (Zhou et al., 1995; Sun et al., 2009) and tumorigenesis (Peng et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2009), it would be interesting to investigate its possible involvement in opioid tolerance as a functional target gene of let-7.

Table 2.

Top 100 predicted targets of let-7 miRNAs ranked by total context score (TargetScan 6.0, http://www.targetscan.org/.)

| Target gene (1–50) | Total context score | Aggregate PCT | Target gene (51–100) | Total context score | Aggregate PCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hmga2 | −1.08 | >0.99 | Map4k3 | −0.46 | 0.96 |

| Fignl2 | −1.07 | >0.99 | Tmem211 | −0.46 | <0.1 |

| Lin28b | −0.98 | >0.99 | Zfp583 | −0.46 | 0.96 |

| Trim71 | −0.98 | >0.99 | Dtx2 | −0.46 | 0.99 |

| Zc3hav1l | −0.85 | 0.86 | Diap2 | −0.46 | 0.98 |

| Fign | −0.84 | >0.99 | Pgrmc1 | −0.46 | 0.9 |

| Nr6a1 | −0.8 | >0.99 | Pars2 | −0.46 | <0.1 |

| 2200002K05Rik | −0.7 | >0.99 | Cd200r1 | −0.45 | 0.94 |

| Skil | −0.67 | >0.99 | Abt1 | −0.45 | <0.1 |

| Igdcc3 | −0.65 | >0.99 | Acot11 | −0.45 | 0.5 |

| Thrsp | −0.62 | <0.1 | Kcnj11 | −0.45 | 0.81 |

| Prtg | −0.61 | >0.99 | Zfp248 | −0.45 | <0.1 |

| Slc5a9 | −0.6 | 0.83 | Bcl2l13 | −0.44 | <0.1 |

| Tgfbr1 | −0.58 | >0.99 | Gatm | −0.44 | 0.95 |

| Yod1 | −0.58 | >0.99 | Hic2 | −0.44 | >0.99 |

| Smarcad1 | −0.57 | 0.96 | Ccnj | −0.44 | 0.97 |

| Gab2 | −0.57 | 0.6 | Arid3a | −0.44 | >0.99 |

| Ngly1 | −0.54 | <0.1 | Hand1 | −0.44 | 0.98 |

| Kctd21 | −0.54 | 0.98 | Igf1r | −0.44 | >0.99 |

| Dna2 | −0.53 | <0.1 | Rpusd3 | −0.43 | 0.59 |

| Ppp1r15b | −0.53 | >0.99 | Pbx3 | −0.43 | 0.99 |

| Nphp3 | −0.53 | 0.94 | Zmat4 | −0.43 | 0.97 |

| Vezt | −0.52 | <0.1 | Tmem164 | −0.43 | <0.1 |

| Suv39h2 | −0.51 | 0.44 | Bcat1 | −0.43 | 0.99 |

| Gdf6 | −0.5 | 0.98 | Pxt1 | −0.43 | <0.1 |

| Brwd1 | −0.5 | <0.1 | Als2cl | −0.43 | <0.1 |

| Coil | −0.49 | 0.97 | 9930012K11Rik | −0.42 | 0.94 |

| Lrig3 | −0.49 | 0.89 | Atg10 | −0.42 | <0.1 |

| Hoxb1 | −0.49 | 0.98 | Limd2 | −0.42 | 0.94 |

| Zcchc9 | −0.48 | <0.1 | Zfp341 | −0.42 | <0.1 |

| B3gnt7 | −0.48 | 0.76 | Fam103a1 | −0.42 | 0.87 |

| Entpd7 | −0.48 | <0.1 | Med28 | −0.42 | 0.56 |

| Acvr1c | −0.48 | 0.99 | Smug1 | −0.42 | <0.1 |

| Lrig2 | −0.48 | 0.99 | Trpm3 | −0.42 | <0.1 |

| Bzw1 | −0.48 | >0.99 | Fras1 | −0.42 | 0.96 |

| Gnptab | −0.48 | 0.98 | Uhrf2 | −0.41 | 0.86 |

| Wdr41 | −0.48 | <0.1 | Cdc25a | −0.41 | 0.8 |

| Cdc34 | −0.47 | 0.99 | Igf2bp1 | −0.41 | >0.99 |

| Slc35d2 | −0.47 | 0.98 | Cep110 | −0.41 | 0.94 |

| Dclre1b | −0.47 | 0.12 | Mrps33 | −0.41 | <0.1 |

| Hif1an | −0.47 | 0.61 | Tnfsf10 | −0.41 | <0.1 |

| Zfp322a | −0.47 | 0.82 | Arhgap28 | −0.41 | 0.98 |

| Adrb2 | −0.47 | 0.98 | Apbb3 | −0.41 | 0.98 |

| Tmprss11f | −0.47 | 0.92 | Fndc3a | −0.41 | 0.97 |

| Ddx19b | −0.47 | 0.98 | Col1a2 | −0.41 | 0.97 |

| Ddx19a | −0.47 | 0.98 | Gemin7 | −0.41 | <0.1 |

| Galnt1 | −0.47 | >0.99 | Wnt9a | −0.41 | 0.99 |

| Greb1l | −0.47 | 0.99 | Igf2bp2 | −0.41 | 0.93 |

| Ercc6 | −0.47 | 0.98 | Tmem2 | −0.41 | 0.98 |

| Ddi2 | −0.46 | 0.89 | Zfp879 | −0.41 | 0.35 |

Seed pairing rules are widely used to predict functional miR target sites. MiR-mRNA recognition requires the perfect complementarity of 6-nucleotide mRNA seed sites with the 5′ end of miRs (positions 2–7; Bartel, 2009). However, when predictions based on such short complementary sequences are compared to experimental results from proteomic studies, the false-positive and false-negative rates appear to be above 50% (Easow et al., 2007; Baek et al., 2008; Mourelatos, 2008; Selbach et al., 2008). Several previous findings strongly indicated that a sizeable fraction of miR targets do not obey the “canonical” seed rule (Ha et al., 1996; Didiano and Hobert, 2006; Tay et al., 2008; Stefani and Slack, 2012). For let-7, biological studies clearly demonstrated that genetically verified let-7 targets in Caenorhabditis elegans contain only imperfect binding sites, with bulges or G·U wobble pairs in the seed region (Vella et al., 2004). A recent study identified a new class of miR target site nucleation bulges and an alternative mode of miR target recognition by a pivot-pairing rule (Chi et al., 2012). They proposed a transitional nucleation model in which a transitional nucleation state determines the binding of miRs to nucleation bulge mRNAs. Therefore, the identification of non-canonical let-7-mRNA interactions may lead to important breakthroughs in discovering new let-7 targets and further decipher the functional role of let-7 in opioid tolerance.

With respect to let-7 target gene identification, another important issue need to be addressed is the redundancy of let-7 family members. There are 14 and 13 different let-7 family members in mouse and human, respectively (Roush and Slack, 2008). In human, these different members, let-7a-1, 7a-2, 7a-3, 7b, 7c, 7d, 7e, f7-1, 7f-2, 7g, 7i, miR-98, and miR-202 are located on nine different chromosomes (Ruby et al., 2006). While let-7 was initially viewed as one single activity, emerging data suggest that the let-7 family contains miRs with different activities (i.e., targets). For example, it has been reported that let-7b* was highly expressed but let-7e* was drastically reduced in malignant mesothelioma (Guled et al., 2009). So the question remains as whether individual let-7 family member with its own expression pattern exerts specialized function during opioid tolerance development.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Opioid tolerance, even to the analgesic actions of these drugs, is likely not caused by a single mechanism; rather an intricate neuronal circuitry involving multiple mechanisms may ultimately lead to the expression of tolerance seen in humans. Regulation of opioid tolerance, through MOR or other mechanisms, represents one of these mechanisms. What is not known is how many miRs are involved. Existing literature on miR-related mechanisms of opioid tolerance is sparse. A typical study in miR research field tends to survey transcript levels of miRs in a disease state (Zheng et al., 2010). For example, morphine-induced up-regulation of miR-15b in human monocyte-derived macrophages (Dave and Khalili, 2010), while miR-133b was decreased by morphine in zebrafish embryos (Sanchez-Simon et al., 2010). It is often extremely difficult to identify a casual relationship. Furthermore, moving from a cell line to in vivo relevance is another big hurdle to overcome.

In the case of let-7 miRs, it was identified as a critical regulator of both human and mouse MOR. Moreover, it was demonstrated to be relevant for both cellular opioid tolerance as well as animal models of opioid tolerance (He et al., 2010). Let-7 represents one of several miRs contributing to opioid tolerance. For example, it was found miR-23b could interact with the MOR 3′-UTR via a K box motif (5′-UGUGAU-3′) in SH-SY5Y and mouse P19 cells (Wu et al., 2008, 2009).

While MOR is involved in the development of morphine tolerance, it is not the only target for the action of miRs in opioid tolerance (Matthes et al., 1996; Sora et al., 1997). With the increasing understanding of miRs in epigenetic regulation, further research is needed to identify other target genes of miRs (including let-7). A number of receptors, ion channels, and protein kinases, which have been implicated in opioid tolerance, such as the NMDA receptors, PKC, and CaMKII (Kieffer and Evans, 2002; Wang and Wang, 2006; Ueda and Ueda, 2009) may become potential targets for let-7.

In summary, miR-mediated mechanisms provide a novel direction toward unraveling the complex mechanisms involved in the development of opioid tolerance. These studies will enrich our knowledge on basic principles of neuronal and behavioral adaptation in opioid tolerance, and eventually lead to novel design and development of pharmacological treatments for opioid tolerance.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

- Ambros V. (2004). The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 10.1038/nature02871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D., Villen J., Shin C., Camargo F. D., Gygi S. P., Bartel D. P. (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455, 64–71 10.1038/nature07242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C. P., Connor M. (2005). Opioids: cellular mechanisms of tolerance and physical dependence. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 5, 60–68 10.1016/j.coph.2004.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. (2009). MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein M. A., Welch S. P. (1998). mu-Opioid receptor down-regulation and cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation in a mouse model of chronic morphine tolerance. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 55, 237–242 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00005-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava H. N., Gulati A. (1990). Down-regulation of brain and spinal cord mu-opiate receptors in morphine tolerant-dependent rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 190, 305–311 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94194-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyerinas B., Park S. M., Hau A., Murmann A. E., Peter M. E. (2010). The role of let-7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, F19–F36 10.1677/ERC-09-0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky M., Elliott K., Hynansky A., Inturrisi C. E. (1995). CNS levels of mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) mRNA during chronic treatment with morphine or naltrexone. Brain Res. Bull. 38, 135–141 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00079-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon W. A., Jr., Duman R. S., Nestler E. J. (2005). The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 28, 436–445 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S., Yang W., Law P. Y., Loh H. H. (1997). The mu-opioid receptor down-regulates differently from the delta-opioid receptor: requirement of a high affinity receptor/G protein complex formation. Mol. Pharmacol. 52, 105–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. W., Duttory A., Yoburn B. C. (1997). Magnitude of tolerance to fentanyl is independent of mu-opioid receptor density. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 319, 225–228 10.1016/S0014-2999(96)00960-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S. W., Hannon G. J., Darnell R. B. (2012). An alternative mode of microRNA target recognition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 321–327 10.1038/nsmb.2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs G., Fazzari M., Kung G., Kawachi N., Brandwein-Gensler M., McLemore M., Chen Q., Burk R. D., Smith R. V., Prystowsky M. B., Belbin T. J., Schlecht N. F. (2009). Low-level expression of microRNAs let-7d and miR-205 are prognostic markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 736–745 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya N., Sherman-Baust C. A., Wang T. L., Davidson B., Shih Ie M., Zhang Y., Wood W., III, Becker K. G., Morin P. J. (2008). MicroRNA expression and identification of putative miRNA targets in ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 3, e2436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave R. S., Khalili K. (2010). Morphine treatment of human monocyte-derived macrophages induces differential miRNA and protein expression: impact on inflammation and oxidative stress in the central nervous system. J. Cell. Biochem. 110, 834–845 10.1002/jcb.22592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. E., Akera T., Brody T. M. (1979). Reduction of opiate binding to brainstem slices associated with the development of tolerance to morphine in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 211, 112–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A., Pazos A., Florez J., Hurle M. A. (2000). Autoradiographic mapping of mu-opioid receptors during opiate tolerance and supersensitivity in the rat central nervous system. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 362, 101–109 10.1007/s002100000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didiano D., Hobert O. (2006). Perfect seed pairing is not a generally reliable predictor for miRNA-target interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 849–851 10.1038/nsmb1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum J., Meyer G., Hollt V., Herz A. (1979). In vivo opiate binding unchanged in tolerant/dependent mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 58, 453–460 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90316-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easow G., Teleman A. A., Cohen S. M. (2007). Isolation of microRNA targets by miRNP immunopurification. RNA 13, 1198–1204 10.1261/rna.563707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guled M., Lahti L., Lindholm P. M., Salmenkivi K., Bagwan I., Nicholson A. G., Knuutila S. (2009). CDKN2A, NF2, and JUN are dysregulated among other genes by miRNAs in malignant mesothelioma -A miRNA microarray analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48, 615–623 10.1002/gcc.20669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. U., Su Y., Zhong C., Ming G. L., Song H. (2011). Hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine by TET1 promotes active DNA demethylation in the adult brain. Cell 145, 423–434 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha I., Wightman B., Ruvkun G. (1996). A bulged lin-4/lin-14 RNA duplex is sufficient for Caenorhabditis elegans lin-14 temporal gradient formation. Genes Dev. 10, 3041–3050 10.1101/gad.10.23.3041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Kasai S., Hata H., Takahashi T., Takamatsu Y., Yamamoto H., Uhl G. R., Sora I., Ikeda K. (2006). Intracisternal a-particle element in the 3′ noncoding region of the mu-opioid receptor gene in CXBK mice: a new genetic mechanism underlying differences in opioid sensitivity. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 16, 451–460 10.1097/01.fpc.0000215072.36965.8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden R. N. (2008). Chronic pain and opiates: a call for moderation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 89, S72–S76 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.09.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Yang C., Kirkmire C. M., Wang Z. J. (2010). Regulation of opioid tolerance by let-7 family microRNA targeting the mu opioid receptor. J. Neurosci. 30, 10251–10258 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0825-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide S., Han W., Kasai S., Hata H., Sora I., Ikeda K. (2005). Characterization of the 3′ untranslated region of the human mu-opioid receptor (MOR-1) mRNA. Gene 364, 139–145 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. E., Chieng B., Napier I., Connor M. (2006). Decreased mu-opioid receptor signalling and a reduction in calcium current density in sensory neurons from chronically morphine-treated mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 148, 947–955 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer B. L., Evans C. J. (2002). Opioid tolerance-in search of the holy grail. Cell 108, 587–590 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00666-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch T., Hollt V. (2008). Role of receptor internalization in opioid tolerance and dependence. Pharmacol. Ther. 117, 199–206 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik K. S. (2006). The neuronal microRNA system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 911–920 10.1038/nrn2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Dutta A. (2007). The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 21, 1025–1030 10.1101/gad.1540407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. W., Lewis M. E., Loomus D. J., Akil H. (1984). Acute systemic administration of morphine selectively increases mu opioid receptor binding in the rat brain. Neuropeptides 5, 117–120 10.1016/0143-4179(84)90041-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gimenez J. F., Milligan G. (2010). Opioid regulation of mu receptor internalisation: relevance to the development of tolerance and dependence. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 9, 616–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield J. H., Harfe B. D., Nissen R., Obenauer J., Srineel J., Chaudhuri A., Farzan-Kashani R., Zuker M., Pasquinelli A. E., Ruvkun G., Sharp P. A., Tabin C. J., McManus M. T. (2004). MicroRNA-responsive ‘sensor’ transgenes uncover Hox-like and other developmentally regulated patterns of vertebrate microRNA expression. Nat. Genet. 36, 1079–1083 10.1038/ng1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini L., Whistler J. L. (2007). The role of mu opioid receptor desensitization and endocytosis in morphine tolerance and dependence. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 556–564 10.1016/j.conb.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes H. W., Maldonado R., Simonin F., Valverde O., Slowe S., Kitchen I., Befort K., Dierich A., Le Meur M., Dolle P., Tzavara E., Hanoune J., Roques B. P., Kieffer B. L. (1996). Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature 383, 819–823 10.1038/383819a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C., Hemann M. T., Bartel D. P. (2007). Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science 315, 1576–1579 10.1126/science.1137999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuay H. (1999). Opioids in pain management. Lancet 353, 2229–2232 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03528-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourelatos Z. (2008). Small RNAs: the seeds of silence. Nature 455, 44–45 10.1038/455044a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino K., Su Y. F., Wong C. S., Watkins W. D., Chang K. J. (1990). Dissociation of mu opioid tolerance from receptor down-regulation in rat spinal cord. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 253, 67–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli A. E., Reinhart B. J., Slack F., Martindale M. Q., Kuroda M. I., Maller B., Hayward D. C., Ball E. E., Degnan B., Muller P., Spring J., Srinivasan A., Fishman M., Finnerty J., Corbo J., Levine M., Leahy P., Davidson E., Ruvkun G. (2000). Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature 408, 86–89 10.1038/35040556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y., Laser J., Shi G., Mittal K., Melamed J., Lee P., Wei J. J. (2008). Antiproliferative effects by Let-7 repression of high-mobility group A2 in uterine leiomyoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 663–673 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowski A. Z. (2011). The role of microRNAs in drug addiction: a big lesson from tiny molecules. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 91, 1–24 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai R. S., Bhattacharyya S. N., Artus C. G., Zoller T., Cougot N., Basyuk E., Bertrand E., Filipowicz W. (2005). Inhibition of translational initiation by Let-7 MicroRNA in human cells. Science 309, 1573–1576 10.1126/science.1115079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z. R., Asa S. L., Siomi H., Siomi M. C., Yoshimoto K., Yamada S., Wang E. L., Rahman M. M., Inoue H., Itakura M., Kudo E., Sano T. (2009). Overexpression of HMGA2 relates to reduction of the let-7 and its relationship to clinicopathological features in pituitary adenomas. Mod. Pathol. 22, 431–441 10.1038/modpathol.2008.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart B. J., Slack F. J., Basson M., Pasquinelli A. E., Bettinger J. C., Rougvie A. E., Horvitz H. R., Ruvkun G. (2000). The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403, 901–906 10.1038/35002607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal W., Carle T. L., Maze I., Covington H. E., III, Truong H. T., Alibhai I., Kumar A., Montgomery R. L., Olson E. N., Nestler E. J. (2008). Delta FosB mediates epigenetic desensitization of the c-fos gene after chronic amphetamine exposure. J. Neurosci. 28, 7344–7349 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1043-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison A. J., Nestler E. J. (2011). Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 623–637 10.1038/nrn3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roush S., Slack F. J. (2008). The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 505–516 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby J. G., Jan C., Player C., Axtell M. J., Lee W., Nusbaum C., Ge H., Bartel D. P. (2006). Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell 127, 1193–1207 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Simon F. M., Zhang X. X., Loh H. H., Law P. Y., Rodriguez R. E. (2010). Morphine regulates dopaminergic neuron differentiation via miR-133b. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 935–942 10.1124/mol.110.066837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman B. R., Esquela-Kerscher A., Slack F. J. (2005). Reciprocal expression of lin-41 and the microRNAs let-7 and mir-125 during mouse embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 234, 1046–1054 10.1002/dvdy.20599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M., Schwanhausser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., Rajewsky N. (2008). Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455, 58–63 10.1038/nature07228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere L. F., Freemantle S., Pitha-Rowe I., Moss E., Dmitrovsky E., Ambros V. (2004). Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 5, R13. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell S., Park S. M., Radjabi A. R., Schickel R., Kistner E. O., Jewell D. A., Feig C., Lengyel E., Peter M. E. (2007). Let-7 expression defines two differentiation stages of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11400–11405 10.1073/pnas.0704148104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L. J., Selley D. E., Dworkin S. I., Childers S. R. (1996). Effects of chronic morphine administration on mu opioid receptor-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS autoradiography in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 16, 2684–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sora I., Takahashi N., Funada M., Ujike H., Revay R. S., Donovan D. M., Miner L. L., Uhl G. R. (1997). Opiate receptor knockout mice define mu receptor roles in endogenous nociceptive responses and morphine-induced analgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 1544–1549 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani G., Slack F. J. (2012). A ‘pivotal’ new rule for microRNA-mRNA interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 265–266 10.1038/nsmb.2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T., Fu M., Bookout A. L., Kliewer S. A., Mangelsdorf D. J. (2009). MicroRNA let-7 regulates 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 925–931 10.1210/me.2009-0092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft R. J., Pang K. C., Mercer T. R., Dinger M., Mattick J. S. (2010). Non-coding RNAs: regulators of disease. J. Pathol. 220, 126–139 10.1002/path.2638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamizawa J., Konishi H., Yanagisawa K., Tomida S., Osada H., Endoh H., Harano T., Yatabe Y., Nagino M., Nimura Y., Mitsudomi T., Takahashi T. (2004). Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 64, 3753–3756 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao P. L., Law P. Y., Loh H. H. (1987). Decrease in delta and mu opioid receptor binding capacity in rat brain after chronic etorphine treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 240, 809–816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay Y., Zhang J., Thomson A. M., Lim B., Rigoutsos I. (2008). MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 455, 1124–1128 10.1038/nature07299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempel A., Habas J., Paredes W., Barr G. A. (1988). Morphine-induced downregulation of mu-opioid receptors in neonatal rat brain. Brain Res. 469, 129–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J. M., Newman M., Parker J. S., Morin-Kensicki E. M., Wright T., Hammond S. M. (2006). Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev. 20, 2202–2207 10.1101/gad.1444406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J. M., Parker J., Perou C. M., Hammond S. M. (2004). A custom microarray platform for analysis of microRNA gene expression. Nat. Methods 1, 47–53 10.1038/nmeth704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H., Ueda M. (2009). Mechanisms underlying morphine analgesic tolerance and dependence. Front. Biosci. 14, 5260–5272 10.2741/3596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella M. C., Choi E. Y., Lin S. Y., Reinert K., Slack F. J. (2004). The C. elegans microRNA let-7 binds to imperfect let-7 complementary sites from the lin-41 3’UTR. Genes Dev. 18, 132–137 10.1101/gad.1165404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. J., Wang L. X. (2006). Phosphorylation: a molecular switch in opioid tolerance. Life Sci. 79, 1681–1691 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. S., Cherng C. H., Luk H. N., Ho S. T., Tung C. S. (1996). Effects of NMDA receptor antagonists on inhibition of morphine tolerance in rats: binding at mu-opioid receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 297, 27–33 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00728-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Law P. Y., Wei L. N., Loh H. H. (2008). Post-transcriptional regulation of mouse mu opioid receptor (MOR1) via its 3′ untranslated region: a role for microRNA23b. FASEB J. 22, 4085–4095 10.1096/fj.08-108175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Zhang L., Law P. Y., Wei L. N., Loh H. H. (2009). Long-term morphine treatment decreases the association of mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) mRNA with polysomes through miRNA23b. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 744–750 10.1124/mol.108.053462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn F. G., Smirnova L., Rybak A., Brandt C., Kwidzinski E., Ninnemann O., Strehle M., Seiler A., Schumacher S., Nitsch R. (2007). Post-transcriptional regulation of the let-7 microRNA during neural cell specification. FASEB J. 21, 415–426 10.1096/fj.06-6130com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V., Bolanos C. A., Selley D. E., Theobald D., Cassidy M. P., Kelz M. B., Shaw-Lutchman T., Berton O., Sim-Selley L. J., Dileone R. J., Kumar A., Nestler E. J. (2006). An essential role for DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 205–211 10.1038/nn1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadina J. E., Chang S. L., Ge L. J., Kastin A. J. (1993). Mu opiate receptor down-regulation by morphine and up-regulation by naloxone in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 265, 254–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Zeng Y., Zhang X., Chu J., Loh H. H., Law P. Y. (2010). mu-Opioid receptor agonists differentially regulate the expression of miR-190 and NeuroD. Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 102–109 10.1124/mol.109.060848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Benson K. F., Ashar H. R., Chada K. (1995). Mutation responsible for the mouse pygmy phenotype in the developmentally regulated factor HMGI-C. Nature 376, 771–774 10.1038/376771a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollner C., Johnson P. S., Bei Wang J., Roy A. J., Jr., Layton K. M., Min Wu J., Surratt C. K. (2000). Control of mu opioid receptor expression by modification of cDNA 5′- and 3′-noncoding regions. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 79, 159–162 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00100-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]