Abstract

Voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSCs) exist as macromolecular complexes containing a pore-forming α subunit and one or more β subunits. The VGSC α subunit gene family consists of ten members, which have distinct tissue-specific and developmental expression profiles. So far, four β subunits (β1–β4) and one splice variant of β1 (β1A, also called β1B) have been identified. VGSC β subunits are multifunctional, serving as modulators of channel activity, regulators of channel cell surface expression, and as members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). β subunits are substrates of β-amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) and γ-secretase, yielding intracellular domains (ICDs) that may further modulate cellular activity via transcription. Recent evidence shows that β1 regulates migration and pathfinding in the developing postnatal central nervous system (CNS) in vivo. The α and β subunits, together with other components of the VGSC signaling complex, may have dynamic interactive roles depending on cell/tissue type, developmental stage, and pathophysiology. In addition to excitable cells like nerve and muscle, VGSC α and β subunits are functionally expressed in cells that are traditionally considered to be non-excitable, including glia, vascular endothelial cells, and cancer cells. In particular, the α subunits are upregulated in line with metastatic potential, and are proposed to enhance cellular migration and invasion. In contrast to the α subunits, β1 is more highly expressed in weakly metastatic cancer cells, and evidence suggests that its expression enhances cellular adhesion. Thus, novel roles are emerging for VGSC α and β subunits in regulating migration during normal postnatal development of the CNS as well as during cancer metastasis.

Keywords: Cancer, Development, Migration, Signaling, Voltage-gated Na+ channel

Introduction

Voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSCs) are heteromeric, polytopic membrane proteins that consist of a single pore-forming α subunit in association with one or more β subunits (Catterall 1992; Catterall 2000). The mammalian α subunit gene family contains ten members, Nav1.1 through Nav1.9 and Nax, encoded by genes SCN1A-SCN11A (Table 1A) (Goldin and others 2000). The different gene products exhibit unique tissue/subcellular distributions and subtle but potentially significant electrophysiological and pharmacological variability (e.g. Clare and others 2000). Additional functional diversity is achieved by alternative mRNA splicing (reviewed in Diss and others 2004). VGSCs are widely expressed in membranes of excitable cells, including neurons, neuroendocrine cells, and skeletal and cardiac myocytes, where they initiate and propagate action potentials (Catterall 1992; Hille 1992). VGSCs have also been identified in traditionally "non-excitable" cells, including glia and human vascular endothelial cells, where their role is less well defined (Barres and others 1990; Gautron and others 1992; Gosling and others 1998).

Table 1.

VGSC isoforms and tissue expression.

| (A) The α subunits. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | Gene symbol (human) | Tissue location |

| Nav1.1 | SCN1A | CNS, PNS, heart |

| Nav1.2 | SCN2A | CNS, PNS |

| Nav1.3 | SCN3A | CNS, PNS |

| Nav1.4 | SCN4A | Skeletal muscle |

| Nav1.5 | SCN5A | Uninnervated skeletal muscle, heart, brain |

| Nav1.6 | SCN8A | CNS, PNS, heart |

| Nav1.7 | SCN9A | PNS, neuroendocrine cells, sensory neurons |

| Nav1.8 | SCN10A | sensory neurons |

| Nav1.9 | SCN11A | sensory neurons |

| Nax | SCN6A, SCN7A | heart, uterus, skeletal muscle, astrocytes, DRG |

| (B) The β subunits. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | Gene symbol (human) | Tissue location |

| β1 | SCN1B | Heart, skeletal muscle, CNS, glia, PNS |

| β1A (β1B) | SCN1B | Heart, skeletal muscle, adrenal gland, PNS |

| β2 | SCN2B | CNS, PNS, heart, glia |

| β3 | SCN3B | CNS, adrenal gland, kidney, PNS |

| β4 | SCN4B | Heart, skeletal muscle, CNS, PNS |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system; DRG, dorsal root ganglia.

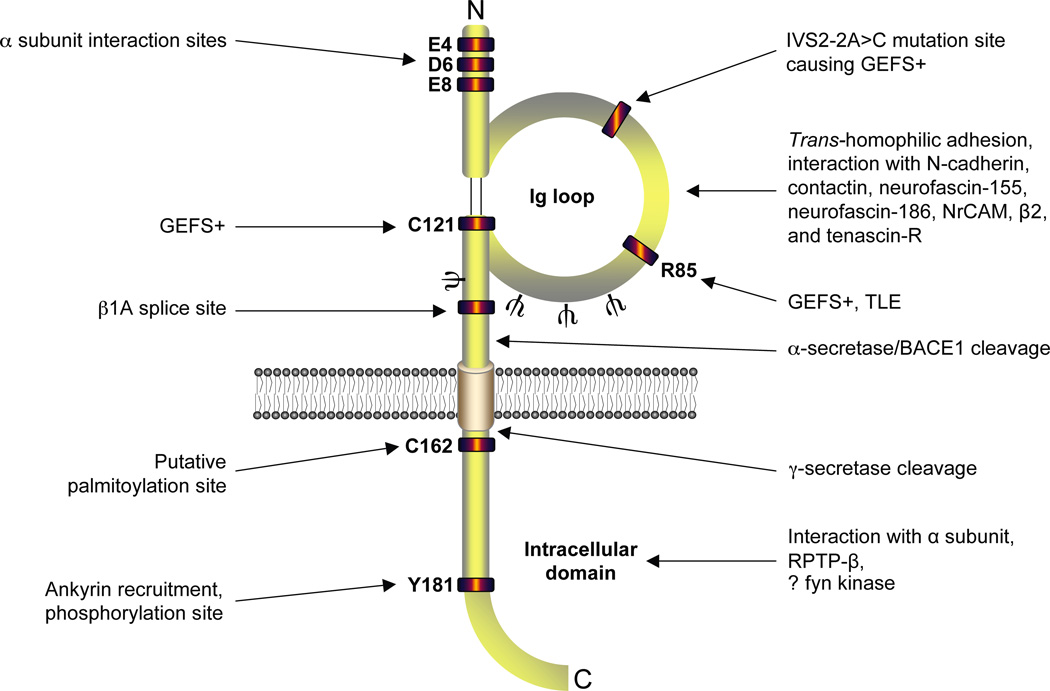

So far, four mammalian VGSC β subunits have been identified: β1 through β4, encoded by genes SCN1B-SCN4B (Table 1B). β1 can also be expressed as the splice variant β1A (also called β1B), containing a novel C-terminus encoded by a retained intron, in a developmentally regulated manner (Kazen-Gillespie and others 2000; Qin and others 2003). β1, β1A/B, and β3 are non-covalently associated with α subunits (Isom and others 1992; Morgan and others 2000). In contrast, β2 and β4 are disulfide-linked to α (Isom and others 1995; Yu and others 2003). VGSC β subunits are multifunctional molecules. β subunits accelerate channel kinetics, shift voltage-dependence, and increase channel cell surface expression when expressed in vitro (Isom and others 1992). They are unique among ion channel auxiliary subunits in that they can also function as immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecules (IGSF-CAMs), promoting adhesion in vitro, both in the presence and absence of α subunits (Isom and Catterall 1996; Isom and others 1994; Malhotra and others 2000; McEwen and others 2004). In addition, β1 interacts with other signaling proteins, including the CAMs contactin, neurofascin, NrCAM, VGSC β2, and cadherin, the extracellular matrix molecule tenascin, receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β (RPTPβ), ankyrinB and ankyrinG (Figure 1) (Malhotra and others 2000; Malhotra and others 2002; McEwen and Isom 2004; Meadows and Isom 2005; Ratcliffe and others 2000; Xiao and others 1999).

Figure 1.

Basic functional architecture of the β1 subunit. Amino acid residues responsible for interaction with α subunit (McCormick and others 1998; Spampanato and others 2004), generalized epilsepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Audenaert and others 2003; Meadows and others 2002; Scheffer and others 2007; Wallace and others 2002), site of intron retention (Kazen-Gillespie and others 2000; Qin and others 2003), putative palmitoylation site (McEwen and others 2004), ankryin interaction site (Malhotra and others 2002) and tyrosine phosphorylation site (Malhotra and others 2004) are shown. Regions identified for N-glycosylation (ψ) (McCormick and others 1998), the Ig loop (Isom and Catterall 1996), BACE1 and α/γ-secretase cleavage (Wong and others 2005), RPTPβ interaction (Ratcliffe and others 2000), and possible fyn kinase interaction (Brackenbury and others 2008; Malhotra and others 2001) are also marked. It should be noted that the C-terminal domain of β1 is also critical for α-β subunit interactions (Spampanato and others 2004). Figure was produced using Science Slides 2006 software.

β1 modulates electrical excitability in vivo: Scn1b null mice are ataxic, display spontaneous generalized seizures, and exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals and slowed cardiac action potentials (Chen and others 2004; Lopez-Santiago and others 2007). Mutations in SCN1B result in human brain disease, including generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Audenaert and others 2003; Meadows and others 2002; Scheffer and others 2007; Wallace and others 2002; Wallace and others 1998). Deletion of β2 (Scn2b) in mice results in reduced tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive VGSC α subunit cell surface functional expression in CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) neurons under basal conditions (Chen and others 2002; Lopez-Santiago and others 2006). Scn2b expression is increased in response to peripheral nerve injury (Pertin and others 2005). Consistent with this, Scn2b null mice exhibit attenuated mechanical allodynia-like behavior in the spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain as well as reduced sensitivity in the late phase of the formalin test (Lopez-Santiago and others 2006; Pertin and others 2005). Interestingly, the absence of β2 in Scn2b null mice is neuroprotective in the experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of Multiple Sclerosis (MS), presumably by preventing VGSC α subunit upregulation in response to demyelination (O'Malley and Isom 2006; Waxman 2008a; Waxman 2008b).

Regulated signaling via complexes of VGSC α and β subunits can control a variety of cellular processes in both neurons as well as cell types that are traditionally thought of as non-excitable, including some types of cancer cells (Chioni and others 2006; Fraser and others 2005; Isom 2001). In this review, we will present the emerging evidence that VGSC α and β subunits play novel roles in cellular migration, focusing upon neuronal development and cancer invasion. These two processes share a number of important characteristics and it has been noted that cancer invasion may be a deregulated process derived from the normal physiological invasion required for development of neuronal wiring during embryogenesis (Liotta and Clair 2000). Furthermore, several aggressive cancers have been found to have ‘neuronal’ characteristics (Onganer and others 2005).

VGSCs in the developing central nervous system

Differential, tissue-specific expression profiles for VGSC α subunit genes during development are well described (e.g. Schaller and Caldwell 2003; Yu and Catterall 2003). Most notably, SCN3A is highly expressed in the fetal CNS, and is subsequently replaced by SCN1A, SCN2A and SCN8A in early postnatal development (Beckh and others 1989; Brysch and others 1991; Gong and others 1999; Schaller and Caldwell 2000). In addition, Nav1.6 protein replaces Nav1.2 protein at the axon initial segment and maturing nodes of Ranvier during myelination in CNS neurons (Boiko and others 2001; Boiko and others 2003; Kaplan and others 2001; Westenbroek and others 1989). Developmentally controlled alternative splicing takes place in domain 1:segment 3 (D1:S3) of SCN2A and SCN3A, resulting in the replacement of a neutral residue in the neonatal splice variant protein by a negatively charged aspartate in the adult form (Diss and others 2004; Gustafson and others 1993; Lu and Brown 1998; Sarao and others 1991). Similar D1:S3 alternative splicing has been reported for SCN5A, SCN8A, and SCN9A, although it is not clear whether this process is developmentally regulated for these orthologous genes (Belcher and others 1995; Fraser and others 2005; Onkal and others 2008; Plummer and others 1998). In the case of SCN5A, the ‘neonatal’ splice variant (nSCN5A) encodes a protein that contains a positively charged lysine in place of the aspartate, which results in a depolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of activation and slower kinetics in vitro, likely due to the charge reversal adjacent to the S4 voltage sensor (Onkal and others 2008). A different alternative splicing event occurs in exon 18 of SCN8A: in fetal brain and non-neuronal tissues, expression of splice variant 18N produces a truncated, non-functional form of the channel, and is replaced later in development by the functional ‘adult’ variant 18A (Plummer and others 1997).

Aberrant expression of VGSC gene products and/or reversion to an earlier developmental expression profile has been observed in several CNS pathophysiologies. For example, in both rodent EAE and human MS, there is an upregulation and redistribution of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 protein in response to axonal demyelination (Craner and others 2003; Craner and others 2004). In addition, sensory neuron specific SCN10A mRNA and Nav1.8 protein are upregulated in cerebellar Purkinje neurons in both a rat demyelinating model and human MS (Black and others 2000; Black and others 1999b). A different situation has been reported in the PNS, where axonal injury causes upregulation of Nav1.3 protein in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Black and others 1999a). Nav1.3 protein expression is also increased in subpopulations of hippocampal neurons in both Scn1a and Scn1b null mice, suggesting that Nav1.3 upregulation in response to altered excitability may be common to the PNS and CNS (Chen and others 2004; Yu and others 2006).

Electrical activity is required for normal morphological development of axons, dendritic spines, and synaptic connections in the mammalian retinogeniculate pathway (Casagrande and Condo 1988; Dubin and others 1986; Kalil and others 1986; Riccio and Matthews 1985; Sretavan and others 1988). The highly specific VGSC blocker TTX reduces the growth of dendritic spines in pyramidal cells in the visual cortex of P21 rats (Riccio and Matthews 1985). In kitten retinal ganglion cells, action potential blockade with TTX inhibits the growth of developing axon terminals and disrupts segregation of retinal synaptic inputs onto cells in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), resulting in a general reduction in the pace of maturation of retinogeniculate synapses in the developing LGN (Casagrande and Condo 1988; Dubin and others 1986; Kalil and others 1986). Although electrical activity appears important for normal development of the visual system, it is not clear if expression/activity of specific VGSC genes is required for CNS development in general. In support of this hypothesis, Scn2a null mice die perinatally with severe brainstem defects, Scn1a null mice die at postnatal day 15 (P15), and Scn8a null mice die between P21–28, suggesting that Nav1.1, Nav1.2, and Nav1.6 all play critical roles in early postnatal CNS development (Harris and Pollard 1986; Planells-Cases and others 2000; Yu and others 2006). In the case of Nav1.1, haploinsufficiency still results in a severe phenotype, supporting the idea that VGSC gene family members may not compensate for each other in vivo. Future studies should ascertain the extent of involvement of different VGSC α subunits in various aspects of activity-dependent postnatal CNS development, in what is clearly a complex, neuron-specific process.

Scn1b mRNA and β1 protein are expressed in CNS neurons from P1, and Scn1b null mice die by P20, indicating a critical role for β1 at this early postnatal developmental stage (Chen and others 2004; Sashihara and others 1995; Sutkowski and Catterall 1990). Given that β1 interacts with a variety of molecules involved in CNS development and axonal pathfinding in addition to α (Malhotra and others 2000; Malhotra and others 2002; McEwen and Isom 2004; Meadows and Isom 2005; Ratcliffe and others 2000; Xiao and others 1999), regulated signaling through complexes of VGSC α and β subunits may be required for normal early postnatal development of the CNS.

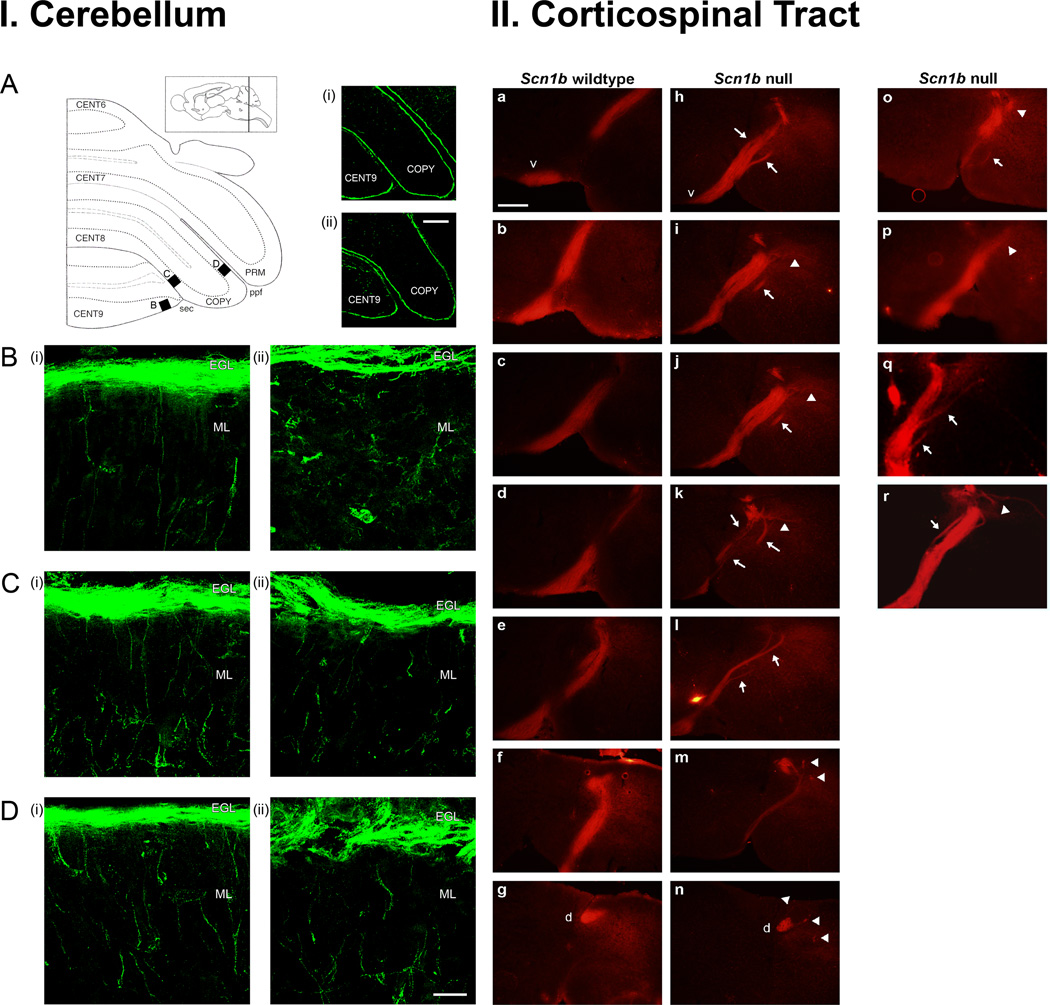

VGSC β subunits and cell adhesion

Increasing evidence suggests that, in addition to regulating electrical excitability, voltage-gated ion channels participate in numerous ‘non-conducting’ signaling mechanisms (reviewed in Kaczmarek 2006). Thus far, the best-characterized non-conducting role of VGSCs is in cell adhesion, via the β subunits. β1 and β2 interact with tenascin-C and tenascin-R, influencing cell migration, and participate in homophilic cell adhesion, resulting in cellular aggregation and ankyrin recruitment (Malhotra and others 2000; Malhotra and others 2002; Srinivasan and others 1998; Xiao and others 1999). In addition, β1 interacts heterophilically with N-cadherin, contactin, neurofascin-155, neurofascin-186, NrCAM and VGSC β2 (Kazarinova-Noyes and others 2001; Malhotra and others 2004; McEwen and Isom 2004; McEwen and others 2004). Interactions between β1 and contactin, neurofascin-186, or β2 result in increased VGSC expression in the plasma membrane in vitro, suggesting that adhesion may modulate excitability (Kazarinova-Noyes and others 2001; McEwen and Isom 2004; McEwen and others 2004). β1 promotes neurite outgrowth in acutely dissociated cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) in culture via trans-homophilic cell adhesive interactions, and this effect is blocked in neurons isolated from Scn1b null mice (Davis and others 2004). Furthermore, β1 functions as a CAM in vivo, and is required for normal early postnatal CNS development. For example, in the cerebellum of P14 Scn1b null mice, the migration of axons through the molecular layer is disrupted, resulting in accumulation of CGNs in the external germinal layer (Figure 2, panel I) (Brackenbury and others 2008). In addition, the absence of β1 results in defasciculation of axons in the developing corticospinal tract (Figure 2, panel II) (Brackenbury and others 2008).

Figure 2.

Scn1b null mice exhibit CNS pathfinding errors.

I. β1 modulates axonal migration in the postnatal developing cerebellum in vivo. (A) Schematic outline of left side of cerebellum in the coronal plane. Black boxes B–D show locations of high-magnification images in (B) – (D). CENT6-9, central lobe, lobules 6–9; COPY, copula pyramidis; PRM, paramedian lobule; sec, secondary fissure; prepyramidal fissure. Inset, parasagittal diagram indicating rostrocaudal location of coronal section. Right-hand plates (i) and (ii): low-magnification images (10X) of TAG-1 immunolabeling (green) on coronal cerebellar sections from Scn1b wildtype, and Scn1b null P14 littermates, respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm. (B) – (D) High-magnification (100X) Z-series projections of the same (i) Scn1b wildtype, and (ii) Scn1b null cerebellar sections, at the locations defined in (A). Scale bar: 20 µm. Three mice of each genotype were examined, with similar results.

II. Loss of β1 results in axonal pathfinding abnormalities in the corticospinal tract. (A) – (G) Consecutive coronal sections across the pyramidal decussation in a Scn1b wildtype brain. (H) – (N) Consecutive coronal sections across the pyramidal decussation in a Scn1b null brain. (O) – (R) Example sections from further Scn1b null mice. Arrows in (H) – (L) and (O) – (R): defasciculation across pyramidal decussation. Arrowheads in (I) – (K) and (O) – (R): mislocalization of axons lateral to dorsal column. Arrowheads in (M), (N): axons deviating from dorsal column after pyramidal decussation. v, ventral pyramid; d, dorsal column. Scale bar, 250 µm. Six Scn1b null mice were examined. All 6 showed similar CST abnormalities compared to 7 wildtype mice. Figure reproduced with permission (Brackenbury and others 2008).

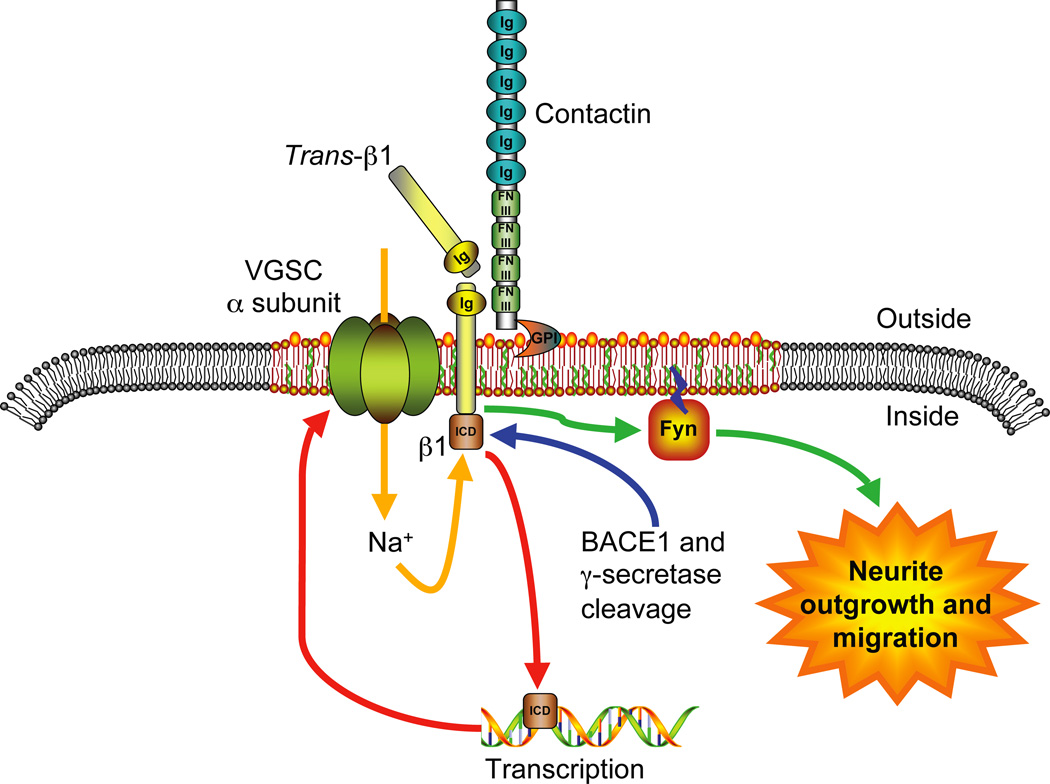

IGSF-CAMs, including β1, are known to localize to lipid rafts (Brackenbury and others 2008; Kasahara and others 2002; Niethammer and others 2002; Olive and others 1995; Schafer and others 2004; Wong and others 2005). Consistent with this, β1 contains a putative palmitoylation site, a common feature of lipid raft-associated proteins (McEwen and others 2004). The mechanism underlying β1-mediated neurite outgrowth involves signaling through the lipid raft-associated non-receptor tyrosine kinase fyn, and requires the presence of the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored CAM contactin (Brackenbury and others 2008). Similarly, NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth is regulated by fyn kinase (Beggs and others 1994; Kolkova and others 2000). A second non-raft associated signaling route via the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) regulates NCAM-mediated, but not β1-mediated neurite outgrowth, suggesting a divergence in the signal transduction pathways mediated by these two IGSF-CAMs (Brackenbury and others 2008; Maness and Schachner 2007; Niethammer and others 2002; Sanchez-Heras and others 2006).

Recently, SCN1B, SCN2B and SCN4B mRNAs have been shown to be expressed in human prostate cancer (PCa) and breast cancer (BCa) cell lines (Chioni and others 2006; Diss and others 2007). Most of this work has been done on BCa, where SCN1B is the most abundantly expressed β subunit gene. SCN1B mRNA and β1 protein levels are significantly higher in the weakly metastatic MCF-7 cell line compared to strongly metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells (Chioni and others 2006). Furthermore, in MCF-7 cells, downregulation of β1 with siRNA decreased adhesion and increased migration (Chioni and others 2006). Therefore, in BCa cells in vitro, β1 may control migration via cell adhesive interactions. In addition, SCN3B, which is not expressed in BCa cells (Chioni and others 2006), contains two response elements to the tumor suppressor p53, and may be involved in p53-dependent apoptosis (Adachi and others 2004), suggesting that absence of SCN3B expression may be an indicator of oncogenesis.

Clearly, the function of β1 as a CAM is important for regulating migration, both in normal neuronal development and in invasive BCa. Further work will be required to ascertain whether downregulation of SCN1B and/or SCN3B in line with oncogenesis and/or increased metastasis may be a global phenomenon in other cancers, and to evaluate the underlying mechanism in the context of oncofetal expression of neuronal genes.

Potential role of VGSC β subunits as transcription factors

All four VGSC β subunit proteins are substrates for sequential cleavage by the β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) and γ-secretase (Wong and others 2005). In addition, β2 is cleaved by the α-secretase enzyme ADAM10 (Kim and others 2005). Processing of β subunits by BACE1/α-secretase at cleavage sites juxtaposed to the extracellular face of the transmembrane region results in ectodomain shedding and yields membrane-bound C-terminal fragments (CTFs) (Figure 1) (Kim and others 2005; Wong and others 2005). In the case of β1, the shed soluble ectodomain may then act as an adhesion ligand in vitro, and promote neurite outgrowth (Davis and others 2004; Malhotra and others 2000). The β-CTFs are further processed by γ-secretase at intracellular sites adjacent to the transmembrane region, yielding small (~12 kDa) intracellular domains (ICDs; Figure 1) (Kim and others 2005; Wong and others 2005). Pharmacological inhibition of β2 cleavage by γ-secretase reduces cell-cell adhesion and migration (Kim and others 2005). Similarly, β4 processing by BACE1 increases neurite outgrowth (Miyazaki and others 2007). These results suggest a functional role for the cleaved β subunit ICDs in the signaling mechanism(s) mediating adhesion, neurite extension and migration.

The β2 ICD released by sequential BACE1 and γ-secretase cleavage localizes to the nucleus and increases SCN1A mRNA and Nav1.1 protein levels, suggesting that the cleaved β2 ICD may function as a transcription regulator (Kim and others 2007). Conversely, downregulation of β1 expression in MCF-7 cells using siRNA results in upregulation of nSCN5A mRNA and ‘neonatal’ Nav1.5 (nNav1.5) protein (Chioni and others 2006). Similarly, Scn1b null mice have increased Scn5a mRNA and Nav1.5 protein expression in cardiomyocytes (Lopez-Santiago and others 2007). Therefore, the β subunit ICDs may function directly or indirectly to regulate transcription of genes including those encoding the VGSC α subunits. In particular, β1 may be a novel widespread regulator of SCN5A expression. Further work should clarify how the β subunit ICDs regulate gene expression, and ascertain the extent of this phenomenon.

Involvement of VGSCs in metastatic cell behaviors of cancer cells

Metastasis, the spreading of cancer cells from a primary neoplasm to form tumors at secondary sites, is of major clinical importance, since this, rather than the primary tumors, is the main cause of cancer-related deaths (Stetler-Stevenson and others 1993). As a result, much research has focused on understanding the mechanisms underlying metastasis with a view to creating novel prognostic markers and therapies with improved accuracy and efficiency (Pantel and Brakenhoff 2004; Schwirzke and others 1999; Weigelt and others 2005). Increasing evidence suggests that strong parallels exist between neuronal development and cancer metastasis (Liotta and Clair 2000). Indeed, physiological invasive and migratory processes integral to neuronal pathfinding in the embryo may be deregulated in the case of pathophysiological cancer invasion (Liotta and others 1991). For example, the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and its polypeptide ligand amphoterin, which colocalize to the leading edge of neurites promoting outgrowth, also increase growth and metastases of implanted and spontaneous tumors in mice (Taguchi and others 2000). Furthermore, in the case of PCa, a subpopulation of cells may undergo neuroendocrine differentiation, and become androgen-independent, highly aggressive, and dependent on growth factor signaling (Abrahamsson 1999; di Sant'Agnese 1992; Kim and others 2002). Given that many embryonic genes are re-expressed in cancer cells (Monk and Holding 2001), it is likely that acquisition of a neuronal phenotype in invasive cancer cells may be an oncofetal phenomenon. Therefore, regulatory processes involved in normal embryonic and/or early postnatal neuronal development may be re-expressed in cancer cells, providing them with a means to migrate and invade during metastasis.

Functional VGSCs are widely expressed in cells from a range of human cancers, including BCa (Fraser and others 2005; Roger and others 2003), PCa (Grimes and others 1995; Laniado and others 1997), lymphoma (Fraser and others 2004), lung cancer (Blandino and others 1995; Onganer and Djamgoz 2005; Roger and others 2007), mesothelioma (Fulgenzi and others 2006), neuroblastoma (Ou and others 2005), melanoma (Allen and others 1997) and cervical cancer (Diaz and others 2007). In addition, VGSC α subunit protein is upregulated in line with metastasis in vivo, in BCa, PCa, and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) biopsy tissues (Abdul and Hoosein 2002; Diss and others 2005; Fraser and others 2005; Onganer and others 2005).

In PCa cells, the predominant VGSC α subunit gene, SCN9A, is upregulated ~1,000-fold at the mRNA level in the strongly metastatic rat Mat-LyLu and human PC-3 cells, compared with the corresponding weakly metastatic AT-2 and LNCaP cells (Diss and others 2001). In BCa cells, mRNA of the most highly expressed α subunit gene, SCN5A, is upregulated 1800-fold in metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells, compared with weakly metastatic MCF-7 cells (Fraser and others 2005). Interestingly, in MDA-MB-231 cells, the DI:S3 5’-splice variant (nSCN5A) is predominant (Chioni and others 2005; Fraser and others 2005). Furthermore, nNav1.5 protein is more highly expressed in the plasma membrane of MDA-MB-231 than MCF-7 cells (Chioni and others 2005; Fraser and others 2005). A similar DI:S3 5’-splice variant of SCN5A has also been described in rat brain tissue and human nB1 neuroblastoma cells (Ou and others 2005; Wang and others 2008).

The VGSC blocker TTX suppresses a variety of in vitro cell behaviors associated with the metastatic cascade in cancer cells (Table 2). VGSC-enhanced behaviors include invasion (Bennett and others 2004; Grimes and others 1995; Laniado and others 1997; Roger and others 2003; Smith and others 1998), transwell migration, (Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2006; Fraser and others 2005; Roger and others 2003), galvanotaxis (Djamgoz and others 2001), morphological development and process extension (Fraser and others 1999), endocytic membrane activity (Mycielska and others 2003; Onganer and Djamgoz 2005), vesicular patterning (Krasowska and others 2004), lateral motility (Fraser and others 2003), reduced adhesion (Palmer and others 2008), nitric oxide production (Williams and Djamgoz 2005) and gene expression (Mycielska and others 2005). Specific functional downregulation of nNav1.5 using RNAi or an antibody (NESO-pAb) revealed that nNav1.5 is primarily responsible for the VGSC-dependent enhancement of migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells (Brackenbury and others 2007). Importantly, transient overexpression of Nav1.4 in weakly metastatic LNCaP cells increases invasion, and can be reversed by TTX, suggesting that VGSC expression is necessary and sufficient to increase their invasive potential (Bennett and others 2004). Finally, the anticonvulsants phenytoin and carbamazepine, which target VGSCs, inhibit secretion of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and interleukin-6 by PCa cells in vitro (Abdul and Hoosein 2001).

Table 2.

Metastatic cell behaviors potentiated by VGSC activity.

| Cellular activity | Cancer/cell line tested | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Process extension | PCa (Mat-LyLu) | Fraser et al. (1999) |

| Galvanotaxis | PCa (Mat-LyLu); BCa (MDA-MB-231) | Djamgoz et al. (2001); Fraser et al. (2005) |

| Lateral motility | PCa (Mat-LyLu); BCa (MDA-MB-231); mesothelioma | Fraser et al. (2003); Fraser et al. (2005); Fulgenzi et al. (2006) |

| Transwell migration | PCa (Mat-LyLu, PC-3M); BCa (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231) | Roger et al. (2003); Fraser et al. (2005); Brackenbury et al. (2006); Onganer and Djamgoz (2007) |

| Endocytic membrane activity | PCa (Mat-LyLu); BCa (MDA-MB-231); SCLC (H69, H209, H510) | Mycielska et al. (2003); Fraser et al. (2005); Onganer and Djamgoz (2005) |

| Vesicular patterning | PCa (Mat-LyLu) | Krasowska et al. (2004) |

| Detachment | PCa (Mat-LyLu, PC-3M); BCa (MCF-7) | Palmer et al. (2008); Chioni et al. (2006) |

| Gene expression | PCa (Mat-LyLu, PC-3M) | Mycielska et al. (2005); Brackenbury and Djamgoz (2006) |

| Matrigel invasion | PCa (Mat-LyLu, PC-3, LNCaP C4 and C4-2); BCa (MDA-MB-231); lymphoma (Jurkat); non-SCLC (H23, H460, Calu-1) | Grimes et al. (1995); Laniado et al. (1997); Smith et al. (1998); Bennett et al. (2004); Roger et al. (2003); Fraser et al. (2004); Fraser et al. (2005); Roger et al. (2007) |

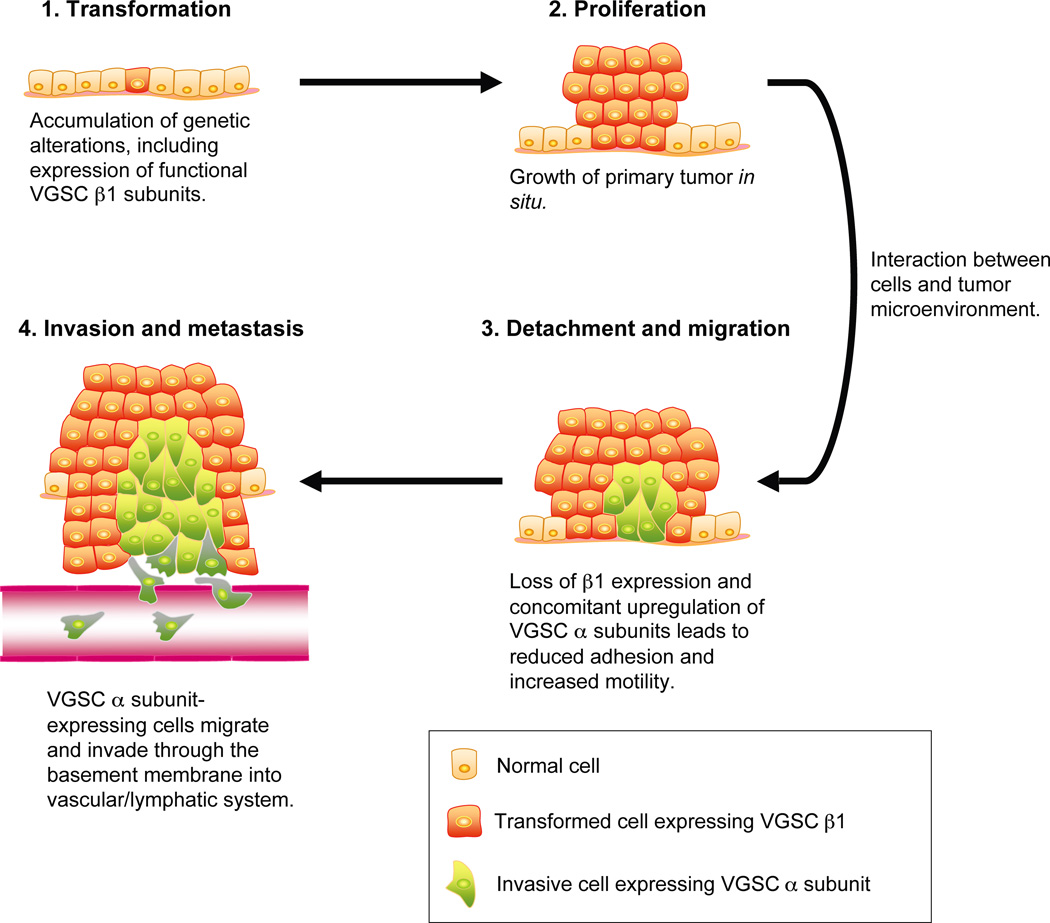

The mechanism(s) responsible for VGSC α subunit upregulation in metastatic cancer cells is not understood. However, serum factors are known to play an important role in this process (Ding and Djamgoz 2004). In Mat-LyLu cells, epidermal growth factor (EGF) increases Na+ current density and enhances migration partially via VGSC activity (Ding and others 2008). Similarly, EGF enhances migration, endocytosis and invasion of PC-3M cells via enhanced SCN9A/Nav1.7 functional expression (Onganer and Djamgoz 2007). In addition, nerve growth factor (NGF) increases Na+ current density in Mat-LyLu cells, although NGF-dependent migration occurs independent of VGSC activity (Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2007). Given that growth factors including NGF play important roles during CNS development, (e.g. von Bartheld 1998), growth factor-dependent regulation of VGSC activity in cancer cells further demonstrates the strong parallel between neuronal development and cancer. Furthermore, the developmental regulator of VGSC expression, REST, has been identified as a candidate oncogene (Armisen and others 2002; Westbrook and others 2005). Steady-state VGSC functional expression in Mat-LyLu cells is maintained by a positive feedback mechanism involving both increased SCN9A transcription and protein kinase A-dependent VGSC trafficking to the plasma membrane, resulting in increased VGSC-dependent cellular migration (Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2006). Given that in MDA-MB-231 cells, the β1 subunit is downregulated, and nNav1.5 is upregulated, β1 itself may regulate α subunit expression/activity, either via transcription, or indirectly, via a CAM-dependent signaling mechanism (Chioni and others 2006). Thus, a complex and dynamic role is emerging for both the VGSC α and β subunits in metastatic cancer progression (Figure 3). Further work is required to elucidate the mode and extent of involvement of the β subunits as novel CAMs in VGSC-dependent metastatic behaviors.

Figure 3.

Proposed model for VGSC α and β subunit involvement in metastatic cancer progression. β1 is expressed in transformed weakly metastatic cancer cells, contributing to their adhesiveness within the proliferating tumor in situ (Chioni and others 2006). In response to signaling interactions between cancer cells and the local tumor microenvironment, VGSC α subunit expression is proposed to be upregulated, and β1 expression downregulated (Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2007; Chioni and others 2006; Ding and others 2008; Ding and Djamgoz 2004; Onganer and Djamgoz 2007). Reduction of β1 is proposed to reduce the cells’ adhesiveness, increasing migration (Chioni and others 2006). The metastatic cells’ migration and invasion is further potentiated by VGSC α subunit activity (Brackenbury and others 2007; Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2006; Smith and others 1998). Figure was produced using Science Slides 2006 software.

Multifunctional roles of VGSC macromolecular signaling complexes in CNS development and cancer progression: concluding remarks

The possibility of VGSC α and β subunits functioning as macromolecular complexes in conjunction with other signaling proteins has been proposed previously, and fits in well with emerging studies identifying various non-conducting roles of voltage-gated channels (Isom 2001; Kaczmarek 2006; Meadows and Isom 2005). The canonical VGSC macromolecular signaling complex would likely comprise at minimum the α subunit together with one or more β subunits, and other interacting partners would vary with cell/tissue type and/or subcellular domain. For example, at the growth cone of migrating CGNs, the VGSC complex is proposed to localize to a lipid raft domain with β1, contactin, and fyn kinase (Figure 4) (Brackenbury and others 2008). Additional components might include cytoskeletal proteins, e.g. ankyrins, and secretases, e.g. BACE1 (Kim and others 2005; Malhotra and others 2000; Malhotra and others 2002; Malhotra and others 2004; Wong and others 2005). In this scenario, the VGSC signaling complex would promote neurite extension in response to β1 trans-adhesive interactions with β1 subunits expressed by adjacent neurons or glia. However, many questions still remain: How does signaling through this complex result in remodeling of the growth cone? How would this signal transduction cascade promote migration and pathfinding in vivo? What is the involvement of VGSC-mediated changes in electrical excitability, if any, on expression/activity of this complex?

Figure 4.

A VGSC macromolecular signaling complex in migrating neurons. A proposed trans-adhesive interaction between β1 on an adjacent neuronal or glial cell and the VGSC macromolecular signaling complex on the cerebellar granule neuron, comprising the α subunit, β1 and contactin, initiates a signaling cascade through fyn kinase leading to neurite outgrowth and migration (Brackenbury and others 2008). In addition, cleavage of β1 by BACE1 and γ-secretase is proposed to release the β1 intracellular domain (ICD), which may enhance transcription of VGSC α subunit(s) (Kim and others 2007; Wong and others 2005). The system may be further fine-tuned by signaling mechanism(s) resulting from Na+ influx through the VGSC α subunit (e.g. Brackenbury and Djamgoz 2006). Figure was produced using Science Slides 2006 software.

Clearly, signaling through VGSC complexes is important for normal CNS development. In addition, aberrant expression/activity of VGSC α and β subunits may be involved in aspects of the cancer process. An important emerging parallel is that VGSC signaling complexes appear to regulate migration of both neurons and cancer cells. The challenge is now to identify the molecular identity of the VGSC macromolecular complexes present under different physiological conditions in vivo, e.g. at different developmental stages, in different cells/tissues. Next, it will be essential to extend this information to understanding how VGSC signaling complexes may operate in pathophysiological situations, including abnormal migration in the developing CNS and metastatic cancer.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis Non-Traditional Postdoctoral Fellowship (WJB), the Pro Cancer Research Fund (MBAD), and NIH R01MH059980 and National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant RG2882 (LLI).

References

- Abdul M, Hoosein N. Inhibition by anticonvulsants of prostate-specific antigen and interleukin-6 secretion by human prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(3B):2045–2048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdul M, Hoosein N. Voltage-gated sodium ion channels in prostate cancer: expression and activity. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(3):1727–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamsson PA. Neuroendocrine cells in tumour growth of the prostate. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6(4):503–519. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi K, Toyota M, Sasaki Y, Yamashita T, Ishida S, Ohe-Toyota M, et al. Identification of SCN3B as a novel p53-inducible proapoptotic gene. Oncogene. 2004;23(47):7791–7798. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen DH, Lepple-Wienhues A, Cahalan MD. Ion channel phenotype of melanoma cell lines. J Membr Biol. 1997;155(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s002329900155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armisen R, Fuentes R, Olguin P, Cabrejos ME, Kukuljan M. Repressor element-1 silencing transcription/neuron-restrictive silencer factor is required for neural sodium channel expression during development of Xenopus. J Neurosci. 2002;22(19):8347–8351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08347.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audenaert D, Claes L, Ceulemans B, Lofgren A, Van Broeckhoven C, De Jonghe P. A deletion in SCN1B is associated with febrile seizures and early-onset absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61(6):854–856. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000080362.55784.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barres BA, Chun LL, Corey DP. Ion channels in vertebrate glia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:441–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckh S, Noda M, Lubbert H, Numa S. Differential regulation of three sodium channel messenger RNAs in the rat central nervous system during development. EMBO J. 1989;8(12):3611–3616. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beggs HE, Soriano P, Maness PF. NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth is inhibited in neurons from Fyn-minus mice. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(3):825–833. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belcher SM, Zerillo CA, Levenson R, Ritchie JM, Howe JR. Cloning of a sodium channel alpha subunit from rabbit Schwann cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(24):11034–11038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett ES, Smith BA, Harper JM. Voltage-gated Na+ channels confer invasive properties on human prostate cancer cells. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447(6):908–914. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black JA, Cummins TR, Plumpton C, Chen YH, Hormuzdiar W, Clare JJ, et al. Upregulation of a silent sodium channel after peripheral, but not central, nerve injury in DRG neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999a;82(5):2776–2785. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black JA, Dib-Hajj S, Baker D, Newcombe J, Cuzner ML, Waxman SG. Sensory neuron-specific sodium channel SNS is abnormally expressed in the brains of mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and humans with multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(21):11598–11602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black JA, Fjell J, Dib-Hajj S, Duncan ID, O'Connor LT, Fried K, et al. Abnormal expression of SNS/PN3 sodium channel in cerebellar Purkinje cells following loss of myelin in the taiep rat. Neuroreport. 1999b;10(5):913–918. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blandino JK, Viglione MP, Bradley WA, Oie HK, Kim YI. Voltage-dependent sodium channels in human small-cell lung cancer cells: role in action potentials and inhibition by Lambert-Eaton syndrome IgG. J Membr Biol. 1995;143(2):153–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00234661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boiko T, Rasband MN, Levinson SR, Caldwell JH, Mandel G, Trimmer JS, et al. Compact myelin dictates the differential targeting of two sodium channel isoforms in the same axon. Neuron. 2001;30(1):91–104. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boiko T, Van Wart A, Caldwell JH, Levinson SR, Trimmer JS, Matthews G. Functional specialization of the axon initial segment by isoform-specific sodium channel targeting. J Neurosci. 2003;23(6):2306–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02306.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brackenbury WJ, Chioni AM, Diss JK, Djamgoz MB. The neonatal splice variant of Nav1.5 potentiates in vitro metastatic behaviour of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;101(2):149–160. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brackenbury WJ, Davis TH, Chen C, Slat EA, Detrow MJ, Dickendesher TL, et al. Voltage-gated Na+ channel β1 subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires fyn kinase and contributes to central nervous system development in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28(12):3246–3256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5446-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brackenbury WJ, Djamgoz MB. Activity-dependent regulation of voltage-gated Na+ channel expression in Mat-LyLu rat prostate cancer cell line. J Physiol. 2006;573(Pt 2):343–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brackenbury WJ, Djamgoz MB. Nerve growth factor enhances voltage-gated Na+ channel activity and transwell migration in Mat-LyLu rat prostate cancer cell line. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(3):602–608. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brysch W, Creutzfeldt OD, Luno K, Schlingensiepen R, Schlingensiepen KH. Regional and temporal expression of sodium channel messenger RNAs in the rat brain during development. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86(3):562–567. doi: 10.1007/BF00230529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casagrande VA, Condo GJ. The effect of altered neuronal activity on the development of layers in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 1988;8(2):395–416. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00395.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catterall WA. Cellular and molecular biology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Physiological Reviews. 1992;72(4):S15–S48. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Bharucha V, Chen Y, Westenbroek RE, Brown A, Malhotra JD, et al. Reduced sodium channel density, altered voltage dependence of inactivation, and increased susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking sodium channel beta 2-subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):17072–17077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212638099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Westenbroek RE, Xu X, Edwards CA, Sorenson DR, Chen Y, et al. Mice lacking sodium channel β1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4030–4042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chioni AM, Fraser SP, Pani F, Foran P, Wilkin GP, Diss JK, et al. A novel polyclonal antibody specific for the Nav 1.5 voltage-gated Na+ channel 'neonatal' splice form. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;147(2):88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chioni AM, Isom LL, Djamgoz MB. Adhesion of human breast cancer cell lines: role of voltage-gated sodium channel β1 subunit. Proc Physiol Soc. 2006;3:PC187. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clare JJ, Tate SN, Nobbs M, Romanos MA. Voltage-gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets. Drug Discov Today. 2000;5(11):506–520. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craner MJ, Lo AC, Black JA, Waxman SG. Abnormal sodium channel distribution in optic nerve axons in a model of inflammatory demyelination. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 7):1552–1561. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craner MJ, Newcombe J, Black JA, Hartle C, Cuzner ML, Waxman SG. Molecular changes in neurons in multiple sclerosis: altered axonal expression of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 sodium channels and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(21):8168–8173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402765101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis TH, Chen C, Isom LL. Sodium channel beta1 subunits promote neurite outgrowth in cerebellar granule neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(49):51424–51432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.di Sant'Agnese PA. Neuroendocrine differentiation in carcinoma of the prostate. Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. Cancer. 1992;70(Suppl)(1):254–268. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1+<254::aid-cncr2820701312>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diaz D, Delgadillo D, Hernandez-Gallegoz E, Ramirez-Dominguez M, Hinojosa L, Ortiz C, et al. Functional expression of voltage-gated sodium channels in primary cultures of human cervical cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:469–478. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding Y, Brackenbury WJ, Onganer PU, Montano X, Porter LM, Bates LF, et al. Epidermal growth factor upregulates motility of Mat-LyLu rat prostate cancer cells partially via voltage-gated Na+ channel activity. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(1):77–81. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Y, Djamgoz MB. Serum concentration modifies amplitude and kinetics of voltage-gated Na+ current in the Mat-LyLu cell line of rat prostate cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(7):1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diss JK, Archer SN, Hirano J, Fraser SP, Djamgoz MB. Expression profiles of voltage-gated Na+ channel alpha-subunit genes in rat and human prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2001;48(3):165–178. doi: 10.1002/pros.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diss JK, Fraser SP, Djamgoz MB. Voltage-gated Na+ channels: multiplicity of expression, plasticity, functional implications and pathophysiological aspects. Eur Biophys J. 2004;33(3):180–193. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diss JK, Fraser SP, Walker MM, Patel A, Latchman DS, Djamgoz MB. beta-Subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels in human prostate cancer: quantitative in vitro and in vivo analyses of mRNA expression. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4501012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diss JK, Stewart D, Pani F, Foster CS, Walker MM, Patel A, et al. A potential novel marker for human prostate cancer: voltage-gated sodium channel expression in vivo. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8(3):266–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Djamgoz MBA, Mycielska M, Madeja Z, Fraser SP, Korohoda W. Directional movement of rat prostate cancer cells in direct-current electric field: involvement of voltage gated Na+ channel activity. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 14):2697–2705. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.14.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubin MW, Stark LA, Archer SM. A role for action-potential activity in the development of neuronal connections in the kitten retinogeniculate pathway. J Neurosci. 1986;6(4):1021–1036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-04-01021.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fraser SP, Ding Y, Liu A, Foster CS, Djamgoz MB. Tetrodotoxin suppresses morphological enhancement of the metastatic MAT-LyLu rat prostate cancer cell line. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;295(3):505–512. doi: 10.1007/s004410051256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraser SP, Diss JK, Chioni AM, Mycielska M, Pan H, Yamaci RF, et al. Voltage-gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5381–5389. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraser SP, Diss JK, Lloyd LJ, Pani F, Chioni AM, George AJ, et al. T-lymphocyte invasiveness: control by voltage-gated Na+ channel activity. FEBS Lett. 2004;569(1–3):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fraser SP, Salvador V, Manning EA, Mizal J, Altun S, Raza M, et al. Contribution of functional voltage-gated Na+ channel expression to cell behaviors involved in the metastatic cascade in rat prostate cancer: I. lateral motility. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(3):479–487. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fulgenzi G, Graciotti L, Faronato M, Soldovieri MV, Miceli F, Amoroso S, et al. Human neoplastic mesothelial cells express voltage-gated sodium channels involved in cell motility. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(7):1146–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gautron S, Dos Santos G, Pinto-Henrique D, Koulakoff A, Gros F, Berwald-Netter Y. The glial voltage-gated sodium channel: cell- and tissue-specific mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(15):7272–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldin AL, Barchi RL, Caldwell JH, Hofmann F, Howe JR, Hunter JC, et al. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;28:365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gong B, Rhodes KJ, Bekele-Arcuri Z, Trimmer JS. Type I and type II Na(+) channel alpha-subunit polypeptides exhibit distinct spatial and temporal patterning, and association with auxiliary subunits in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412(2):342–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gosling M, Harley SL, Turner RJ, Carey N, Powell JT. Human saphenous vein endothelial cells express a tetrodotoxin-resistant, voltage-gated sodium current. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(33):21084–21090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grimes JA, Fraser SP, Stephens GJ, Downing JE, Laniado ME, Foster CS, et al. Differential expression of voltage-activated Na+ currents in two prostatic tumour cell lines: contribution to invasiveness in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1995;369(2–3):290–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gustafson TA, Clevinger EC, O'Neill TJ, Yarowsky PJ, Krueger BK. Mutually exclusive exon splicing of type III brain sodium channel alpha subunit RNA generates developmentally regulated isoforms in rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(25):18648–18653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris JB, Pollard SL. Neuromuscular transmission in the murine mutants "motor end-plate disease" and "jolting". J Neurol Sci. 1986;76(2–3):239–253. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(86)90172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. Sunderland (Massachusetts): Sinauer Associates Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Isom LL. Sodium channel β subunits: anything but auxiliary. The Neuroscientist. 2001;7:42–54. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isom LL, Catterall WA. Na+ channel subunits and Ig domains. Nature. 1996;383(6598):307–308. doi: 10.1038/383307b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Catterall WA. Auxiliary subunits of voltage-gated ion channels. Neuron. 1994;12:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Patton DE, Reber BF, Offord J, Charbonneau H, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 1992;256(5058):839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1375395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isom LL, Ragsdale DS, De Jongh KS, Westenbroek RE, Reber BF, Scheuer T, et al. Structure and function of the beta 2 subunit of brain sodium channels, a transmembrane glycoprotein with a CAM motif. Cell. 1995;83(3):433–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaczmarek LK. Non-conducting functions of voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(10):761–771. doi: 10.1038/nrn1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalil RE, Dubin MW, Scott G, Stark LA. Elimination of action potentials blocks the structural development of retinogeniculate synapses. Nature. 1986;323(6084):156–158. doi: 10.1038/323156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaplan MR, Cho MH, Ullian EM, Isom LL, Levinson SR, Barres BA. Differential control of clustering of the sodium channels Na(v)1.2 and Na(v)1.6 at developing CNS nodes of Ranvier. Neuron. 2001;30(1):105–119. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kasahara K, Watanabe K, Kozutsumi Y, Oohira A, Yamamoto T, Sanai Y. Association of GPI-anchored protein TAG-1 with src-family kinase Lyn in lipid rafts of cerebellar granule cells. Neurochem Res. 2002;27(7–8):823–829. doi: 10.1023/a:1020265225916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kazarinova-Noyes K, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, Mattei LN, Berglund EO, Ranscht B, et al. Contactin associates with Na+ channels and increases their functional expression. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7517–7525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07517.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kazen-Gillespie KA, Ragsdale DS, D’Andrea MR, Mattei LN, Rogers KE, Isom LL. Cloning, localization, and functional expression of sodium channel β1A subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:1079–1088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim DY, Carey BW, Wang H, Ingano LA, Binshtok AM, Wertz MH, et al. BACE1 regulates voltage-gated sodium channels and neuronal activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(7):755–764. doi: 10.1038/ncb1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim DY, Mackenzie Ingano LA, Carey BW, Pettingell WP, Kovacs DM. Presenilin/gamma -secretase-mediated cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channel beta 2 subunit regulates cell adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(24):23251–23261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim J, Adam RM, Freeman MR. Activation of the Erk mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway stimulates neuroendocrine differentiation in LNCaP cells independently of cell cycle withdrawal and STAT3 phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2002;62(5):1549–1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kolkova K, Novitskaya V, Pedersen N, Berezin V, Bock E. Neural cell adhesion molecule-stimulated neurite outgrowth depends on activation of protein kinase C and the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20(6):2238–2246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02238.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krasowska M, Grzywna ZJ, Mycielska ME, Djamgoz MB. Patterning of endocytic vesicles and its control by voltage-gated Na+ channel activity in rat prostate cancer cells: fractal analyses. Eur Biophys J. 2004;33(6):535–542. doi: 10.1007/s00249-004-0394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Laniado ME, Lalani EN, Fraser SP, Grimes JA, Bhangal G, Djamgoz MB, et al. Expression and functional analysis of voltage-activated Na+ channels in human prostate cancer cell lines and their contribution to invasion in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(4):1213–1221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leshchyns'ka I, Sytnyk V, Morrow JS, Schachner M. Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) association with PKCbeta2 via betaI spectrin is implicated in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(3):625–639. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liotta LA, Clair T. Cancer. Checkpoint for invasion. Nature. 2000;405(6784):287–288. doi: 10.1038/35012728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liotta LA, Steeg PS, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Cancer metastasis and angiogenesis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cell. 1991;64(2):327–336. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90642-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopez-Santiago LF, Meadows LS, Ernst SJ, Chen C, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, et al. Sodium channel Scn1b null mice exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43(5):636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lopez-Santiago LF, Pertin M, Morisod X, Chen C, Hong S, Wiley J, et al. Sodium channel beta2 subunits regulate tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in small dorsal root ganglion neurons and modulate the response to pain. J Neurosci. 2006;26(30):7984–7994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2211-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu CM, Brown GB. Isolation of a human-brain sodium-channel gene encoding two isoforms of the subtype III alpha-subunit. J Mol Neurosci. 1998;10(1):67–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02737087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malhotra J, Chen C, Rivolta I, Abriel H, Malhotra R, Mattei LN, et al. Characterization of sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1303–1310. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malhotra JD, Kazen-Gillespie K, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Sodium channel β subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact. J Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11383–11388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel β1 subunits with ankyrin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(29):26681–26688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malhotra JD, Thyagarajan V, Chen C, Isom LL. Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated sodium channel beta1 subunits are differentially localized in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):40748–40754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maness PF, Schachner M. Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(1):19–26. doi: 10.1038/nn1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McCormick KA, Isom LL, Ragsdale D, Smith D, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Na+ channel function in the extracellular domain of the beta1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(7):3954–3962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McEwen DP, Isom LL. Heterophilic interactions of sodium channel beta1 subunits with axonal and glial cell adhesion molecules. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(50):52744–52752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McEwen DP, Meadows LS, Chen C, Thyagarajan V, Isom LL. Sodium channel β1 subunit-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents and cell surface density is dependent on interactions with contactin and ankyrin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16044–16049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meadows LS, Isom LL. Sodium channels as macromolecular complexes: implications for inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67(3):448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meadows LS, Malhotra J, Loukas A, Thyagarajan V, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Koopman MC, et al. Functional and biochemical analysis of a sodium channel β1 subunit mutation responsible for Generalized Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus Type 1. J. Neurosci. 2002;22(24):10699–10709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10699.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miyazaki H, Oyama F, Wong HK, Kaneko K, Sakurai T, Tamaoka A, et al. BACE1 modulates filopodia-like protrusions induced by sodium channel beta4 subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monk M, Holding C. Human embryonic genes re-expressed in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20(56):8085–8091. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morgan K, Stevens EB, Shah B, Cox PJ, Dixon AK, Lee K, et al. beta 3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(5):2308–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030362197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mycielska ME, Fraser SP, Szatkowski M, Djamgoz MB. Contribution of functional voltage-gated Na+ channel expression to cell behaviors involved in the metastatic cascade in rat prostate cancer: II. Secretory membrane activity. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(3):461–469. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mycielska ME, Palmer CP, Brackenbury WJ, Djamgoz MB. Expression of Na+-dependent citrate transport in a strongly metastatic human prostate cancer PC-3M cell line: regulation by voltage-gated Na+ channel activity. J Physiol. 2005;563(Pt 2):393–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Niethammer P, Delling M, Sytnyk V, Dityatev A, Fukami K, Schachner M. Cosignaling of NCAM via lipid rafts and the FGF receptor is required for neuritogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(3):521–532. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Malley HA, Isom LL. The role of sodium channel β2 sbunits in neuroprotection. Society for Neuroscience (Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2006 727.2/D61. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Olive S, Dubois C, Schachner M, Rougon G. The F3 neuronal glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked molecule is localized to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains and interacts with L1 and fyn kinase in cerebellum. J Neurochem. 1995;65(5):2307–2317. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Onganer PU, Djamgoz MB. Small-cell lung cancer (human): potentiation of endocytic membrane activity by voltage-gated Na+ channel expression in vitro. J Membr Biol. 2005;204(2):67–75. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Onganer PU, Djamgoz MB. Epidermal growth factor potentiates in vitro metastatic behaviour of human prostate cancer PC-3M cells: Involvement of voltage-gated sodium channel. Mol Cancer. 2007;6(1):76. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Onganer PU, Seckl MJ, Djamgoz MB. Neuronal characteristics of small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1197–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Onkal R, Mattis JH, Fraser SP, Diss JK, Shao D, Okuse K, et al. Alternative splicing of Nav1.5: An electrophysiological comparison of 'neonatal' and 'adult' isoforms and critical involvement of a lysine residue. J Cell Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jcp.21451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ou SW, Kameyama A, Hao LY, Horiuchi M, Minobe E, Wang WY, et al. Tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ channels in human neuroblastoma cells are encoded by new variants of Nav1.5/SCN5A. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(4):793–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Palmer CP, Mycielska ME, Burcu H, Osman K, Collins T, Beckerman R, et al. Single cell adhesion measuring apparatus (SCAMA): application to cancer cell lines of different metastatic potential and voltage-gated Na+ channel expression. Eur Biophys J. 2008;37(4):359–368. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH. Dissecting the metastatic cascade. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(6):448–456. doi: 10.1038/nrc1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pertin M, Ji RR, Berta T, Powell AJ, Karchewski L, Tate SN, et al. Upregulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel β2 subunit in neuropathic pain models: characterization of expression in injured and non-injured primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25(47):10970–10980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3066-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Planells-Cases R, Caprini M, Zhang J, Rockenstein EM, Rivera RR, Murre C, et al. Neuronal death and perinatal lethality in voltage-gated sodium channel alpha(II)-deficient mice. Biophys J. 2000;78(6):2878–2891. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76829-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Plummer NW, Galt J, Jones JM, Burgess DL, Sprunger LK, Kohrman DC, et al. Exon organization, coding sequence, physical mapping, and polymorphic intragenic markers for the human neuronal sodium channel gene SCN8A. Genomics. 1998;54(2):287–296. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Plummer NW, McBurney MW, Meisler MH. Alternative splicing of the sodium channel SCN8A predicts a truncated two-domain protein in fetal brain and non-neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(38):24008–24015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.24008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Qin N, D'Andrea MR, Lubin ML, Shafaee N, Codd EE, Correa AM. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the human sodium channel beta1B subunit, a novel splicing variant of the beta1 subunit. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270(23):4762–4770. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ratcliffe CF, Qu Y, McCormick KA, Tibbs VC, Dixon JE, Scheuer T, et al. A sodium channel signaling complex: modulation by associated receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β. Nature Neurosci. 2000;3:437–444. doi: 10.1038/74805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Riccio RV, Matthews MA. Effects of intraocular tetrodotoxin on dendritic spines in the developing rat visual cortex: a Golgi analysis. Brain Res. 1985;351(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Roger S, Besson P, Le Guennec JY. Involvement of a novel fast inward sodium current in the invasion capacity of a breast cancer cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1616(2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Roger S, Rollin J, Barascu A, Besson P, Raynal PI, Iochmann S, et al. Voltage-gated sodium channels potentiate the invasive capacities of human non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(4):774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sanchez-Heras E, Howell FV, Williams G, Doherty P. The fibroblast growth factor receptor acid box is essential for interactions with N-cadherin and all of the major isoforms of neural cell adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(46):35208–35216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sarao R, Gupta SK, Auld VJ, Dunn RJ. Developmentally regulated alternative RNA splicing of rat brain sodium channel mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(20):5673–5679. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sashihara S, Oh Y, Black JA, Waxman SG. Na+ channel β1 subunit mRNA expression in developing rat central nervous system. Molecular Brain Research. 1995;34:239–250. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00168-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schafer DP, Bansal R, Hedstrom KL, Pfeiffer SE, Rasband MN. Does paranode formation and maintenance require partitioning of neurofascin 155 into lipid rafts? J Neurosci. 2004;24(13):3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5427-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schaller KL, Caldwell JH. Developmental and regional expression of sodium channel isoform NaCh6 in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2000;420(1):84–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schaller KL, Caldwell JH. Expression and distribution of voltage-gated sodium channels in the cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2003;2(1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/14734220309424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Scheffer IE, Harkin LA, Grinton BE, Dibbens LM, Turner SJ, Zielinski MA, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy and GEFS+ phenotypes associated with SCN1B mutations. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 1):100–109. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schwirzke M, Schiemann S, Gnirke AU, Weidle UH. New genes potentially involved in breast cancer metastasis. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(3A):1801–1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Smith P, Rhodes NP, Shortland AP, Fraser SP, Djamgoz MB, Ke Y, et al. Sodium channel protein expression enhances the invasiveness of rat and human prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;423(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Spampanato J, Kearney JA, de Haan G, McEwen DP, Escayg A, Aradi I, et al. A novel epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A identifies a cytoplasmic domain for beta subunit interaction. J Neurosci. 2004;24(44):10022–10034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sretavan DW, Shatz CJ, Stryker MP. Modification of retinal ganglion cell axon morphology by prenatal infusion of tetrodotoxin. Nature. 1988;336(6198):468–471. doi: 10.1038/336468a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Srinivasan J, Schachner M, Catterall WA. Interaction of voltage-gated sodium channels with the extracellular matrix molecules tenascin-C and tenascin-R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(26):15753–15757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Aznavoorian S, Liotta LA. Tumor cell interactions with the extracellular matrix during invasion and metastasis. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:541–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sutkowski EM, Catterall WA. β1 Subunits of sodium channels. Studies with subunit-specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:12393–12399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Taguchi A, Blood DC, del Toro G, Canet A, Lee DC, Qu W, et al. Blockade of RAGE-amphoterin signalling suppresses tumour growth and metastases. Nature. 2000;405(6784):354–360. doi: 10.1038/35012626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.von Bartheld CS. Neurotrophins in the developing and regenerating visual system. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13(2):437–459. doi: 10.14670/HH-13.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wallace RH, Scheffer IE, Parasivam G, Barnett S, Wallace GB, Sutherland GR, et al. Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus: mutation of the sodium channel subunit SCN1B. Neurology. 2002;58(9):1426–1429. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.9.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wallace RH, Wang DW, Singh R, Scheffer IE, George AL, Jr, Phillips HA, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19(4):366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang J, Ou SW, Wang YJ, Zong ZH, Lin L, Kameyama M, et al. New variants of Nav1.5/SCN5A encode Na+ channels in the brain. J Neurogenet. 2008;22(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/01677060701672077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Waxman SG. Axonal dysfunction in chronic multiple sclerosis: Meltdown in the membrane. Ann Neurol. 2008a doi: 10.1002/ana.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Waxman SG. Mechanisms of disease: sodium channels and neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis-current status. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008b;4(3):159–169. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van 't Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(8):591–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Westbrook TF, Martin ES, Schlabach MR, Leng Y, Liang AC, Feng B, et al. A genetic screen for candidate tumor suppressors identifies REST. Cell. 2005;121(6):837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Westenbroek RE, Merrick DK, Catterall WA. Differential subcellular localization of the RI and RII Na+ channel subtypes in central neurons. Neuron. 1989;3(6):695–704. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Williams EL, Djamgoz MB. Nitric oxide release from strongly metastatic MAT-LyLu rat prostate cancer cells: Control by voltage-gated sodium channels. J Physiol. 2005;565P:PC116. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wong HK, Sakurai T, Oyama F, Kaneko K, Wada K, Miyazaki H, et al. beta subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels are novel substrates of BACE1 and gamma -secretase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(24):23009–23017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Xiao ZC, Ragsdale DS, Malhotra JD, Mattei LN, Braun PE, Schachner M, et al. Tenascin-R is a functional modulator of sodium channel beta subunits. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(37):26511–26517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yu FH, Catterall WA. Overview of the voltage-gated sodium channel family. Genome Biol. 2003;4(3):207. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yu FH, Mantegazza M, Westenbroek RE, Robbins CA, Kalume F, Burton KA, et al. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(9):1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Silos-Santiago I, McCormick KA, Lawson D, Ge P, et al. Sodium channel beta4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to beta2. J Neurosci. 2003;23(20):7577–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]