Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the accuracy of specific biochemical markers for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

METHODS: One hundred and fifty-four patients with chronic HCV infection were included in this study; 124 patients were non-cirrhotic, and 30 were cirrhotic. The following measurements were obtained in all patients: serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time and concentration, complete blood count, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HCVAb, HCV-RNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, abdominal ultrasound and ultrasonic-guided liver biopsy. The following ratios, scores and indices were calculated and compared with the results of the histopathological examination: AST/ALT ratio (AAR), age platelet index (API), AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), cirrhosis discriminating score (CDS), Pohl score, Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index (GUCI).

RESULTS: AAR, APRI, API and GUCI demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy of liver cirrhosis (80.5%, 79.2%, 76.6% and 80.5%, respectively); P values were: < 0.01, < 0.05, < 0.001 and < 0.001, respectively. Among the studied parameters, AAR and GUCI gave the highest diagnostic accuracy (80.5%) with cutoff values of 1.2 and 1.5, respectively. APRI, API and GUCI were significantly correlated with the stage of fibrosis (P < 0.001) and the grade of activity (P < 0.001, < 0.001 and < 0.005, respectively), while CDS only correlated significantly with the stage of fibrosis (P < 0.001) and not with the degree of activity (P > 0.05). In addition, we found significant correlations for the AAR, APRI, API, GUCI and Pohl score between the non-cirrhotic (F0, F1, F2, F3) and cirrhotic (F4) groups (P values: < 0.001, < 0.05, < 0.001, < 0.001 and < 0.005, respectively; CDS did not demonstrate significant correlation (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The use of AAR, APRI, API, GUCI and Pohl score measurements may decrease the need for liver biopsies in diagnosing cirrhosis, especially in Egypt, where resources are limited.

Keywords: Age platelet index, Aspartate aminotransferase platelet ratio index, Aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio, Cirrhosis discriminating score, Fibrosis evaluation, Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index, Hepatitis C virus infection, Liver fibrosis, Pohl score

INTRODUCTION

Egypt has the highest prevalence of adult hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the world, affecting an average of 15%-25% of the population in rural communities[1,2].Worldwide, HCV is one of the major causes of chronic liver diseases, which include inflammation, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Furthermore, HCV has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in hepatocellular carcinoma[3-5].

Although liver biopsy is an invasive procedure and includes a risk of complications, such as pain, pneumothorax, puncture of other viscera and hemorrhage, it is still the gold standard for grading the severity of necroinflammation and staging the extent of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic HCV infection[6-8].

In addition to the added cost, liver biopsy cannot be performed universally in all patients with impaired hemostasis of any origin[9]. The procedure is known to underestimate liver fibrosis when small tissue samples are collected, and it is prone to intra- and inter-observer variation[10-13]. Moreover, several studies have suggested that liver biopsy is far from being a perfect diagnostic tool because its accuracy in detecting pathology is dependent on the size of the biopsy[14-17]. Previous reports have proposed that a liver biopsy sample should contain a minimum of 5 portal tracts and be at least 15 mm in length to be considered adequate[18-20]. Other authors have recommended even larger samples[21]. In 2003, a French survey reported that liver biopsy may be refused by up to 59% of patients[22]. In 2005, an Italian survey reported major discrepancies among hepatologists regarding when and how to take a liver biopsy from the same subgroup of chronic hepatitis C patients[23].

Considering these limitations, many studies have recently focused on the development of non-invasive markers as surrogates of liver biopsy[24-34]. An accurate assessment of hepatic fibrosis can be achieved with various markers and indices. In this study, we aimed to assess the validity of six markers of hepatic fibrosis, including the ratio of aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio (AAR), AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), age platelet index (API), cirrhosis discriminating score (CDS), Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index (GUCI) and Pohl score, in grading fibrosis and diagnosing early cirrhosis as an accurate alternative to liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection in a country known to have a high prevalence of the disease[1,2].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study included 154 patients with chronic HCV infection. They were selected from the gastroenterology and hepatology clinics of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt, over the period from March 2009 to November 2010. All selected patients were potential candidates for interferon therapy.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection, autoimmune hepatitis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, history of previous antiviral therapy and presence of absolute contraindication for liver biopsy were excluded from this study.

Methods

All patients were subjected to full history intake, thorough physical examination and the following laboratory test measurements: serum ALT, AST, albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time and concentration, complete blood count, HCV antibody (anti-HCV), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HCV-RNA by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR), circulating autoantibodies (ANA, ASMA), abdominal ultrasonography and ultrasonographic guided liver biopsy.

Liver biopsies were performed using 18-20 gauge Trucut needles (GMSS.N, GHATWARY MEDICAL). To assess necroinflammation, the grade of activity was evaluated using a modified hepatic activity index: mild (0-6), moderate (7-12) and severe (13-18). Fibrosis was staged according to the METAVIR scoring system from F0 to F4. Based on the results obtained from histopathological assessment of their liver biopsies, patients were divided into two groups:the non-cirrhotic group (F0, F1, F2 and F3) and the cirrhotic group (F4).

Definition of the noninvasive indices

The following ratios, scores and indices[24-34] were calculated and compared with the results of histopathological examination: (1) AAR; (2) APRI, calculated using the following equation: (AST/upper limit of normal)/platelet count (× 109/L) × 10; (3) API, calculated by summing the scores awarded for the following patient laboratory results (a possible value of 0-10): age (in years) < 30 = 0; 30-39 = 1; 40-49 = 2; 50-59 = 3; 60-69 = 4; ≥ 70 = 5; platelet count (× 109/L): ≥ 225 = 0; 200-224 = 1; 175-199 = 2; 150-174 = 3; 125-149 = 4; < 125 = 5; (4) CDS, calculated by summing the scores awarded for the following patient laboratory results (a possible value of 0-11): platelet count (× 109/L): > 340 = 0; 280-339 = 1; 220-279 = 2; 160-219 = 3; 100-159 = 4; 40-99 = 5; < 40 = 6. ALT/AST ratio: > 1.7 = 0; 1.2-1.7 = 1; 0.6-1.19 = 2; < 0.6 = 3. International normalized ratio (INR): < 1.1 = 0; 1.1-1.4 = 1; > 1.4 = 2; (5) GUCI, calculated using the following equation: normalized AST × INR × 100/ platelet count (× 109/L); and (6) Pohl score,which was considered positive if the AAR was ≥ 1 and the platelet count was < 150 × 109/L. The Ethics committee at our institution approved the study, and all patients provided informed consent before participating in this study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included range, mean ± SD, median, frequencies (number of cases) and percentages when appropriate. Comparisons of numerical variables between the study groups were made using the Mann Whitney U test for independent samples. To compare categorical data, the Chi squared (χ2) test was used.When the expected frequency was less than 5, the Exact test was used instead. Accuracy was represented using the terms sensitivity and specificity. Receiver operator characteristic analysis was used to determine the optimum cutoff value for the studied diagnostic markers. Various variables were tested for correlation using the Spearman rank correlation equation for non-normal variables. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Normality of data was checked by the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Most of our markers violated the normal assumption; therefore, the data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. Two-tailed tests were used where appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression determined only API to be significantly associated with diagnosis of cirrhosis in our cases. No other variable was found to be a significant predictor of cirrhosis. All statistical calculations were performed using the computer programs Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, NY, United States) and SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) version 15 for Microsoft Windows.

RESULTS

Demographic and baseline laboratory data of non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The demographic and laboratory data of all patients (mean ± SD)

| Item | Non-cirrhotic group (F0, F1, F2 and F3) | Cirrhotic group (F4) | P value |

| n (124) | n (30) | ||

| Age, yr | 37.19 ± 9.58 | 47.87 ± 7.76 | 0.0002 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 86 (69.35) | 18 (60) | |

| Female | 38 (30.65) | 12 (40) | |

| AST (IU/mL) | 48.84 ± 42.7 | 61 ± 20.4 | 0.01 |

| ALT (IU/mL) | 60.235 ± 42.3 | 57.7 ± 24.69 | 0.68 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 81.654 ± 38.4 | 111 ± 42.5 | 0.004 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.787 ± 0.30 | 1.003 ± 0.38 | 0.07 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 5.803 ± 0.789 | 4.1 ± 0.42 | 0.004 |

| INR | 1.127 ± 0.092 | 1.254 ± 0.12 | 0.0001 |

| Platelet count (/mm3) | 213.75 ± 66.1 | 151.87 ± 73.79 | 0.001 |

| HCV viraemia, IU/mL | 893 015.72 ± 1 571 254.86 | 347 974.86 ± 536 542.77 | 0.23 |

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; INR: International normalized ratio; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

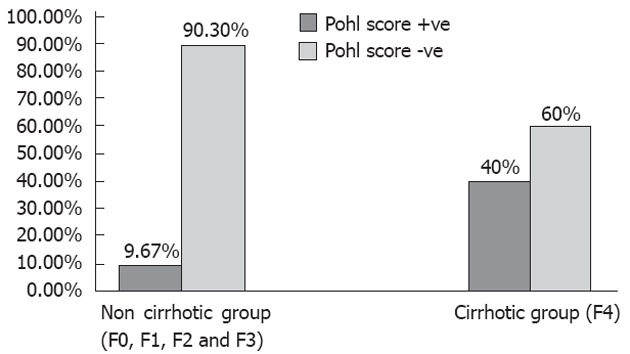

Our findings demonstrated a statistically significant correlation for AAR, APRI, API, GUCI and Pohl score between the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients; CDS was not found to be significant. Pohl score was positive (indicating cirrhosis) in 40% of cirrhotic patients, whereas it was positive in only 9.67% of non-cirrhotic patients, with a P value of 0.004 (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Positive and negative Pohl score in non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection.

Table 2.

Mean values (± SD) of aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, age platelet index, cirrhosis discriminating score and Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index in non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic groups of chronic hepatitis C virus infected patients

| Variable | Non-cirrhotic group (F0, F1, F2 and F3), n (124) | Cirrhotic group (F4), n (30) | P value |

| AAR | 0.84 ± 0.31 | 1.23 ± 0.47 | 0.001 |

| APRI | 0.078 ± 0.09 | 0.118 ± 0.07 | 0.02 |

| API | 2.98 ± 2.21 | 5.87 ± 1.99 | 0.0001 |

| CDS | 5.48 ± 1.36 | 6 ± 1.31 | 0.17 |

| GUCI | 0.913 ± 1.27 | 1.6573 ± 0.89 | 0.001 |

| Pohl score | +ve 12 (9.67%) | +ve 12 (40%) | 0.004 |

| -ve 112 (90.3%) | -ve 18 (60%) |

AAR: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; API: Age platelet index; CDS: Cirrhosis discriminating score; GUCI: Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index.

Patient age, AST and platelet count correlated significantly with both the grade of activity and the stage of fibrosis. However, neither ALT nor HCV RNA load demonstrated statistically significant correlations with the grade of activity or the stage of fibrosis. With regard to other laboratory parameters, INR, albumin and alkaline phosphatase levels were significantly correlated with stage of fibrosis but not with grade of activity, whereas serum bilirubin was significantly correlated with grade of activity but not with stage of fibrosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

The correlation between age and variable laboratory data, and the stage of fibrosis and grade of necroinflammatory activity

| Variable |

Stage of fibrosis |

Grade of activity |

||

| Correlation coefficient | P value | Correlation coefficient | P value | |

| Age | 0.4 | 0.0003 | 0.3 | 0.005 |

| AST | 0.3 | 0.003 | 0.3 | 0.006 |

| ALT | 0.2 | 0.07 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.3 | 0.006 | 0.2 | 0.08 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.2 | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.003 |

| Albumin | -0.3 | 0.002 | -0.2 | 0.08 |

| INR | 0.4 | 0.001 | 0.2 | 0.13 |

| Platelet count | -0.5 | 0.000001 | -0.4 | 0.0002 |

| HCV RNA load | -0.07 | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.5 |

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; INR: International normalized ratio; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

The results of our study revealed a significant correlation between APRI, API and GUCI, and both the grade of activity and the stage of fibrosis. CDS correlated significantly with the stage of liver fibrosis but not with the grade of necroinflammatory activity. In contrast, the AST/ALT ratio had no significant correlation with either the stage of fibrosis or the grade of activity (Table 4).

Table 4.

The correlation between the aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio, aspartate aminotransferase- to-platelet ratio index, age platelet index, cirrhosis discriminating score and Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index and the grade of necroinflammatory activity and the stage of fibrosis

| Variable |

Stage of fibrosis |

Grade of activity |

||

| Correlation coefficient | P value | Correlation coefficient | P value | |

| AAR | 0.2 | 0.054 | 0.1 | 0.23 |

| APRI | 0.4 | 0.00006 | 0.4 | 0.001 |

| API | 0.6 | 0.000001 | 0.5 | 0.00002 |

| CDS | 0.4 | 0.0002 | 0.2 | 0.056 |

| GUCI | 0.5 | 0.0001 | 0.3 | 0.003 |

AAR: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; API: Age platelet index; CDS: Cirrhosis discriminating score; GUCI: Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index.

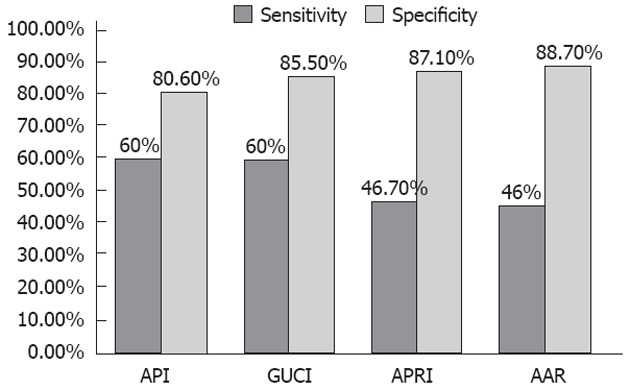

For non-invasive diagnosis of liver cirrhosis (F4), using AAR, APRI, API and GUCI, Table 5 and Figure 2 show the cutoff values, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV), and area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of these parameters.

Table 5.

The accuracy of different ratios and indices in the diagnosis of early liver cirrhosis

| Item | Cutoff value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) | AUROC | P value |

| AAR | 1.2 | 46 | 88.7 | 50 | 87.3 | 80.5 | 0.761 | 0.002 |

| APRI | 1.36 | 46.7 | 87.1 | 46.7 | 87.1 | 79.2 | 0.697 | 0.018 |

| API | 5.5 | 60 | 80.6 | 42.9 | 89.3 | 76.6 | 0.826 | 0.000 |

| GUCI | 1.56 | 60 | 85.5 | 50 | 89.8 | 80.5 | 0.783 | 0.001 |

AAR: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-alanine aminotransferase ratio; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; API: Age platelet index; GUCI: Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; AUROC: Area under the receiver operating characteristics.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of age platelet index, Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio in diagnosing cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. API: Age platelet index; GUCI: Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index; APRI: Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; AAR: Aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio.

DISCUSSION

Although it is costly, requires hospitalization for at least 6-18 h, is invasive and carries a risk of complications with an associated morbidity rate between 0.3% and 0.6% and mortality rate of 0.05%, liver biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing liver histology[34-36]. However, limitations of liver biopsy include the underestimation of fibrosis stage, given that only 1/50 000 of the organ is removed[37], and the reported inter- and intra-observer discrepancies rates of 10%-20%[38,39].

In this study, we found that the optimal cutoff AARvalue for diagnosing cirrhosis was ≥ 1.2, with a sensitivity of 46%, specificity of 88.7% and PPV and NPV of 50% and 87.3%, respectively. These results support previous findings by Giannini et al[40], who recommended an AAR value of ≥ 1 as a cutoff value for diagnosing cirrhosis. However, Ehsan et al[41] reported a higher cutoff value (≥ 1.5) for diagnosing cirrhosis, with a sensitivity of 44% and a specificity of 91%.

Elevation of the AST/ALT ratio in cirrhotic patients may be explained by the reduction in AST clearance, which leads to an increase in serum AST levels. In addition, advanced liver disease may be associated with mitochondrial injury, resulting in increased release of AST present in the mitochondria and cytoplasm[42].

Thrombocytopenia in patients with advanced fibrosis may be due to reduced hepatic production of thrombopoietin, increased splenic sequestration of platelets secondary to portal hypertension or the myelosuppressive action of HCV[43,44].

Results from the current study revealed a significant correlation between APRI and both the stage of liver fibrosis and the grade of activity. The optimal cutoff APRI value for the diagnosis of cirrhosis was ≥ 1.36, which was consistent with findings by Ichino et al[45] and Ehsan et al[41], who reported cutoff values of 1.3 and 1.5, respectively.

In the present study, we found a significant correlation between API and both the stage of fibrosis and the grade of activity (P < 0.001 for both). Our results revealed that the optimal AP index cutoff value for the diagnosis of cirrhosis was ≥ 5.5, with 60% and 80.6% sensitivity and specificity, respectively, and 42.86% and 89.29% PPV and NPV, respectively. The results of the current study are in agreement with the results of previous studies by Lackner et al[46] and Poynard et al[47].

Results from this study showed that there was a significant correlation between GUCI and both the stage of liver fibrosis and the grade of activity. We recommend a GUCI value of ≥ 1.56 as an optimal cutoff value for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, with 60% sensitivity, 88.7% specificity, and a PPV and NPV of 89.83% and 80.52%, respectively. These results supported those reported by Islam et al[48], who found a significant correlation between GUCI and both stage of fibrosis and grade of activity. Similar results were reported by Ehsan et al[41], who recommended a GUCI cutoff value of ≥ 1.5 for the diagnosis of cirrhosis, with 89% specificity and 74% sensitivity.

In the present study, we found a statistically significant correlation (P = 0.004) between positive Pohl score (AAR ≥ 1, and platelet count < 150 × 109/L) and the presence of cirrhosis (F4). These findings supported the results of Pohl et al[27] and Lackner et al[46], who confirmed the diagnostic accuracy of the Pohl score in significant fibrosis and cirrhosis.

In our study, there was a significant correlation between CDS and stage of liver fibrosis (P < 0.001), but the relationship was not significant with regard to the grade of activity (P = 0.056). The CDS values were not significant between the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients (P = 0.17), which disagreed with results reported by Ichino et al[45], who recommended a CDS value of ≥ 8 as a cutoff value for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Some studies showed no correlation between the histological outcome and HCV-RNA levels, while other reports suggested that the viral titer may influence the severity of liver damage and that high titer viremia correlates with the most severe liver damage[49]. The current study revealed no significant correlation between HCV RNA load as measured by quantitative PCR and both the grade of activity and fibrosis stage.

Our results agreed with the studies conducted by Lee et al[50] and Saleem et al[51]. In contrast, Kato et al[52] found significantly higher HCV RNA loads in patients with chronic active hepatitis and cirrhosis compared to those with chronic persistent hepatitis. These discrepancies could be attributed to the fact that serum HCV RNA load is not a stable parameter because it fluctuates[53]. In addition, a high amount of circulating HCV does not always imply a more active state of viral replication in the liver nor does it indicate a more severe degree of liver disease. HCV is known to replicate both within the liver as well as in extra-hepatic sites[54,55].

In conclusion, the API index, APRI, AST/ALT ratio and GUCI showed good accuracy, moderate sensitivity, and high specificity for the diagnosis of early cirrhosis. These measures also demonstrated significant correlation with both the stage of liver fibrosis and the grade of activity. The combination of these non-invasive biochemical markers may replace the requirement for liver biopsy, particularly for cases with cirrhosis or early cirrhotic changes in which the procedure has known limitations and complications.

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major causes of chronic liver diseases worldwide. It has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in hepatocellular carcinoma. In patients with chronic HCV infection, liver biopsy is essential to the assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Evaluating the degree of fibrosis is an important step in determining the need and priority for treatment with antiviral drugs. However, liver biopsy is a costly and invasive procedure with a risk of complications and a tendency to underestimate liver fibrosis. Hence, alternative non-invasive diagnostic tools are needed.

Research frontiers

In the area of liver cirrhosis assessment, the focus of research is on how to use biochemical markers and indices [aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio (AAR), AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), age platelet index (API), cirrhosis discriminating score (CDS), Göteborg University Cirrhosis Index (GUCI) and Pohl score] calculated from simple routine laboratory tests, such as serum levels of bilirubin, ALT, AST, albumin and platelet count, to determine the severity of liver fibrosis and to evaluate their accuracy in comparison to liver biopsy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results showed that APRI, API, GUCI and CDS were significantly correlated with the degree of liver fibrosis. AAR, APRI, API, GUCI and Pohl score can accurately diagnose early liver cirrhosis. AAR and GUCI gave the highest accuracy for the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis (80.5%). These simple biochemical markers, especially when used in combination, may decrease the use of liver biopsy in the assessment of fibrosis and diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with chronic HCV infection.

Applications

The study results suggest that these biochemical markers can identify significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic HCV; their combined application may decrease the need for liver biopsy, thereby reducing its associated costs and complications. Important fields for further study include the use and evaluation of these markers for repeated assessment in monitoring the progression of liver fibrosis and its regression following interferon treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

Terminology

CDS, GUCI and Pohl score are indices calculated to develop noninvasive diagnostic markers of liver fibrosis depending on simple biochemical tests such as platelet count, AST and ALT.

Peer review

In this paper, the authors focused on the noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis in Egyptian patients with chronic HCV infection using different indexes. It is potentially interesting and well-written and provides useful information in a selected population with a high prevalence of chronic HCV infection.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Yusuf Yilmaz, MD, Department of Gastro-enterology, Marmara University, School of Medicine, Fevzi Cakmak Mah, Mimar Sinan Cad. No. 41 Ust Kaynarca, Pendik, 34899 Istanbul, Turkey

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Abdel-Wahab MF, Zakaria S, Kamel M, Abdel-Khaliq MK, Mabrouk MA, Salama H, Esmat G, Thomas DL, Strickland GT. High seroprevalence of hepatitis C infection among risk groups in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:563–567. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, Lavanchy D, Arthur RR, Magder LS, El Khoby T, Abdel-Wahab Y, Aly Ohn ES, Anwar W, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet. 2000;355:887–891. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaheen AA, Myers RP. Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology. 2007;46:912–921. doi: 10.1002/hep.21835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sebastiani G. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis in chronic liver diseases: implementation in clinical practice and decisional algorithms. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2190–2203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin ZH, Xin YN, Dong QJ, Wang Q, Jiang XJ, Zhan SH, Sun Y, Xuan SY. Performance of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the staging of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53:726–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.24105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin M, Poujol-Robert A, Boëlle PY, Wendum D, Lasnier E, Viallon M, Guéchot J, Hoeffel C, Arrivé L, Tubiana JM, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46:658–665. doi: 10.1002/hep.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sebastiani G, Halfon P, Castera L, Pol S, Thomas DL, Mangia A, Di Marco V, Pirisi M, Voiculescu M, Guido M, et al. SAFE biopsy: a validated method for large-scale staging of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2009;49:1821–1827. doi: 10.1002/hep.22859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Attar MM, Rashed HG, Sewify EM, Hassan HE. A suggested algorithm for using serum biomarkers for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C infection. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2010;11:206–211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1994;20:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller S, Millonig G, Sarovska L, Friedrich S, Reimann FM, Pritsch M, Eisele S, Stickel F, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, et al. Increased liver stiffness in alcoholic liver disease: differentiating fibrosis from steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:966–972. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naveau S, Gaudé G, Asnacios A, Agostini H, Abella A, Barri-Ova N, Dauvois B, Prévot S, Ngo Y, Munteanu M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic values of noninvasive biomarkers of fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:97–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.22576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontana RJ, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, Bonkovsky HL, Naishadham D, Sterling RK, Su GL, Ghosh M, Wright EC. Relationship of serum fibrosis markers with liver fibrosis stage and collagen content in patients with advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2008;47:789–798. doi: 10.1002/hep.22099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, Fontaine H, Pol S. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedossa P, Carrat F. Liver biopsy: the best, not the gold standard. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poynard T, Muntenau M, Morra R, Ngo Y, Imbert-Bismut F, Thabut D, Messous D, Massard J, Lebray P, Moussalli J, et al. Methodological aspects of the interpretation of non-invasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis: a 2008 update. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:8–21. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedossa P, Dargère D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afdhal NH, Nunes D. Evaluation of liver fibrosis: a concise review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1160–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hübscher SG. Histological grading and staging in chronic hepatitis: clinical applications and problems. J Hepatol. 1998;29:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlichting P, Hølund B, Poulsen H. Liver biopsy in chronic aggressive hepatitis. Diagnostic reproducibility in relation to size of specimen. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:27–32. doi: 10.3109/00365528309181554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheuer PJ. Liver biopsy size matters in chronic hepatitis: bigger is better. Hepatology. 2003;38:1356–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonny C, Rayssiguier R, Ughetto S, Aublet-Cuvelier B, Baranger J, Blanchet G, Delteil J, Hautefeuille P, Lapalus F, Montanier P, et al. [Medical practices and expectations of general practitioners in relation to hepatitis C virus infection in the Auvergne region] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:1021–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almasio PL, Niero M, Angioli D, Ascione A, Gullini S, Minoli G, Oprandi NC, Pinzello GB, Verme G, Andriulli A. Experts’ opinions on the role of liver biopsy in HCV infection: a Delphi survey by the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (A.I.G.O.) J Hepatol. 2005;43:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Şirli R, Ioan S, Bota S, Popescu A, Cornianu M. A Comparative Study of Non-Invasive Methods for Fibrosis Assessment in Chronic HCV Infection. Hepat Mon. 2010;10:88–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yilmaz Y, Yonal O, Kurt R, Bayrak M, Aktas B, Ozdogan O. Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis with the aspartate transaminase to platelet ratio index (APRI): Usefulness in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:103–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leroy V. Other non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:52–57. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinzani M. Non-invasive evaluation of hepatic fibrosis: don’t count your chickens before they’re hatched. Gut. 2006;55:310–312. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.068585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pohl A, Behling C, Oliver D, Kilani M, Monson P, Hassanein T. Serum aminotransferase levels and platelet counts as predictors of degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3142–3146. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sebastiani G, Alberti A. Non invasive fibrosis biomarkers reduce but not substitute the need for liver biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3682–3694. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leroy V, Halfon P, Bacq Y, Boursier J, Rousselet MC, Bourlière M, de Muret A, Sturm N, Hunault G, Penaranda G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy, reproducibility and robustness of fibrosis blood tests in chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis with individual data. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:1368–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinzani M, Vizzutti F, Arena U, Marra F. Technology Insight: noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by biochemical scores and elastography. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:95–106. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lok AS, Ghany MG, Goodman ZD, Wright EC, Everson GT, Sterling RK, Everhart JE, Lindsay KL, Bonkovsky HL, Di Bisceglie AM, et al. Predicting cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis C based on standard laboratory tests: Results of the HALT-C cohort. Hepatology. 2005;42:282–292. doi: 10.1002/hep.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva Jr RG, Fakhouri R, Nascimento TV, Santos IM, Barbosa LM. Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for fibrosis and cirrhosis prediction in chronic hepatitis C patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loaeza-del-Castillo A, Paz-Pineda F, Oviedo-Cárdenas E, Sánchez-Avila F, Vargas-Vorácková F. AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) for the noninvasive evaluation of liver fibrosis. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:350–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Degos F, Perez P, Roche B, Mahmoudi A, Asselineau J, Voitot H, Bedossa P. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study) J Hepatol. 2010;53:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poynard T, Imbert-Bismut F, Munteanu M, Messous D, Myers RP, Thabut D, Ratziu V, Mercadier A, Benhamou Y, Hainque B. Overview of the diagnostic value of biochemical markers of liver fibrosis (FibroTest, HCV FibroSure) and necrosis (ActiTest) in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cadranel JF, Rufat P, Degos F. Practices of liver biopsy in France: results of a prospective nationwide survey. For the Group of Epidemiology of the French Association for the Study of the Liver (AFEF) Hepatology. 2000;32:477–481. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong JB, Koff RS. Watchful waiting with periodic liver biopsy versus immediate empirical therapy for histologically mild chronic hepatitis C. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:665–675. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-9-200011070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colloredo G, Guido M, Sonzogni A, Leandro G. Impact of liver biopsy size on histological evaluation of chronic viral hepatitis: the smaller the sample, the milder the disease. J Hepatol. 2003;39:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, Milikowski C, Molina EG, Pyrsopoulos NT, Feng ZZ, Reddy KR, Schiff ER. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giannini E, Risso D, Botta F, Chiarbonello B, Fasoli A, Malfatti F, Romagnoli P, Testa E, Ceppa P, Testa R. Validity and clinical utility of the aspartate aminotransferase-alanine aminotransferase ratio in assessing disease severity and prognosis in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:218–224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ehsan N, TawfikBadr MT, Raouf AA, Badra G. Correlation Between Liver Biopsy Findings and Different Serum Biochemical Tests in Staging Fibrosis in Egyptian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2008;9:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okuda M, Li K, Beard MR, Showalter LA, Scholle F, Lemon SM, Weinman SA. Mitochondrial injury, oxidative stress, and antioxidant gene expression are induced by hepatitis C virus core protein. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:366–375. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peck-Radosavljevic M. Hypersplenism. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:317–323. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai CY, Ho CK, Huang JF, Hsieh MY, Hou NJ, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Hsieh MY, Wang LY, Chang WY, et al. Hepatitis C virus viremia and low platelet count: a study in a hepatitis B & amp; C endemic area in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2010;52:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichino N, Osakabe K, Nishikawa T, Sugiyama H, Kato M, Kitahara S, Hashimoto S, Kawabe N, Harata M, Nitta Y, et al. A new index for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4809–4816. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i38.4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lackner C, Struber G, Liegl B, Leibl S, Ofner P, Bankuti C, Bauer B, Stauber RE. Comparison and validation of simple noninvasive tests for prediction of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1376–1382. doi: 10.1002/hep.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poynard T, Bedossa P. Age and platelet count: a simple index for predicting the presence of histological lesions in patients with antibodies to hepatitis C virus. METAVIR and CLINIVIR Cooperative Study Groups. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:199–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Islam S, Antonsson L, Westin J, Lagging M. Cirrhosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients can be excluded using an index of standard biochemical serum markers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:867–872. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anand BS, Velez M. Assessment of correlation between serum titers of hepatitis C virus and severity of liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2409–2411. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee YS, Yoon SK, Chung ES, Bae SH, Choi JY, Han JY, Chung KW, Sun HS, Kim BS, Kim BK. The relationship of histologic activity to serum ALT, HCV genotype and HCV RNA titers in chronic hepatitis C. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:585–591. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saleem N, Mubarik A, Qureshi AH, Siddiq M, Ahmad M, Afzal S, Hussain AB, Hashmi SN. Is there a correlation between degree of viremia and liver histology in chronic hepatitis C? J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:476–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kato N, Yokosuka O, Hosoda K, Ito Y, Ohto M, Omata M. Quantification of hepatitis C virus by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction: increase of the virus in advanced liver disease. Hepatology. 1993;18:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeuzem S, Schmidt JM, Lee JH, Rüster B, Roth WK. Effect of interferon alfa on the dynamics of hepatitis C virus turnover in vivo. Hepatology. 1996;23:366–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Müller HM, Pfaff E, Goeser T, Kallinowski B, Solbach C, Theilmann L. Peripheral blood leukocytes serve as a possible extrahepatic site for hepatitis C virus replication. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 4):669–676. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-4-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ballardini G, Manzin A, Giostra F, Francesconi R, Groff P, Grassi A, Solforosi L, Ghetti S, Zauli D, Clementi M, et al. Quantitative liver parameters of HCV infection: relation to HCV genotypes, viremia and response to interferon treatment. J Hepatol. 1997;26:779–786. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]