Abstract

Recent studies indicate that the human brain attends to and uses grammatical gender cues during sentence comprehension. Here, we examine the nature and time course of the effect of gender on word-by-word sentence reading. Event-related brain potentials were recorded to an article and noun, while native Spanish speakers read medium- to high-constraint Spanish sentences for comprehension. The noun either fit the sentence meaning or not, and matched the preceding article in gender or not; in addition, the preceding article was either expected or unexpected based on prior sentence context. Semantically anomalous nouns elicited an N400. Gender-disagreeing nouns elicited a posterior late positivity (P600), replicating previous findings for words. Gender agreement and semantic congruity interacted in both the N400 window—with a larger negativity frontally for double violations—and the P600 window—with a larger positivity for semantic anomalies, relative to the prestimulus baseline. Finally, unexpected articles elicited an enhanced positivity (500–700 msec post onset) relative to expected articles. Overall, our data indicate that readers anticipate and attend to the gender of both articles and nouns, and use gender in real time to maintain agreement and to build sentence meaning.

INTRODUCTION

When asked to complete the sentence “Little Red Riding Hood carried the food for her grandmother in…,” most readers say “a basket,” although Red could have easily carried the food in “a sack.” In English, words like “basket” and “sack” differ primarily in their meaning (e.g., semantically); in contrast, in approximately half of the world's languages, nouns can differ syntactically by gender, as well. In these languages, all nouns and their associated articles, adjectives, and pronouns have a grammatical gender. For example, in Spanish—a two-gender language, “a basket” is feminine, una canasta (although masculine alternatives exist, e.g., un sesto, una canasta is preferred by our population of interest based on prior norming studies), but “a sack” is masculine, un costal. Thus, the equivalent Spanish sentence “Caperucita Roja cargaba la comida para su abuela en…” is best completed by the feminine article una followed by the noun canasta. The current study takes advantage of this feature of Spanish to explore sentence comprehension in real time, with two specific goals. First, we ask whether grammatical gender agreement affects the integration of a noun into a written sentence context, and if so, whether this process differs for semantically congruous versus incongruous words. To address these issues, we recorded event-related brain potentials (ERPs) from the scalps of native Spanish speakers as they read sentences like the Red Riding Hood example above and observed the brain's response to a target noun that was either expected (e.g., basket–canasta) or semantically incongruous, hence unexpected (e.g., crown–corona), and either agreed or disagreed with its preceding article in gender (e.g., una canasta/corona vs. un canasta/corona, respectively). Second, we also took advantage of the obligatory agreement in Spanish between gender-marked articles and nouns to ask whether individuals generate expectations for upcoming words based on sentence context, and if so, whether these include information about that word's grammatical gender. To this end, we examined the nature of the brain activity in response to the article, when it agreed with the gender of the noun that best fit the sentence context compared with when it did not. If readers develop expectations for a noun of specific gender, then brain activity should differ for articles with contextually expected versus contextually unexpected gender; that is, a violation of this expectation should be evident in the average brain activity elicited by the processing of the article, even before the (unexpected) noun appears. This study was designed to address these two distinct questions about the role of grammatical gender in sentence comprehension; each will be treated separately herein.

Appreciation of Grammatical Gender Agreement

To produce or comprehend a sentence properly, speakers of languages with a rich gender system must maintain agreement between words at various levels of processing, from morphological agreement between gender-marked articles and nouns (e.g., una canasta) to discourse-level agreement between gender-marked pronouns and the nouns to which they refer. Studies using ERPs have provided electrophysiological evidence for the brain's sensitivity to gender agreement during sentence comprehension (e.g., Wicha, Bates, Moreno, & Kutas, 2003; Wicha, Moreno, & Kutas, 2003; Deutsch & Bentin, 2001; Brown, van Berkum, & Hagoort, 2000; Gunter, Friederici, & Schriefers, 2000; Hagoort & Brown, 1999; Hagoort, 2003; van Berkum, Brown, & Hagoort, 1999). These ERP studies have consistently revealed a gender (dis)agreement effect for items that disagree in gender with a prior gender-marked word, albeit different effects for word and picture targets. Gender-disagreeing words have generally been associated with a late posterior positivity (e.g., Deutsch & Bentin, 2001; Brown et al., 2000; Gunter et al., 2000; Demestre, Meltzer, Garcia-Albea, & Vigil, 1999; Hagoort & Brown, 1999; van Berkum et al., 1999), sometimes accompanied by an earlier frontal negativity (e.g., Deutsch & Bentin, 2001; Gunter et al., 2000; Demestre et al., 1999). For example, in Spanish sentences such as “Pedro es rico/rica”—“Pedro [masc] is rich [masc]/rich [fem],” Demestre et al. (1999) found a larger positivity to adjectives that mismatched in gender (e.g., rica) with the preceding noun referent (e.g., Pedro) than to those that matched in gender (e.g., rico), with a maximal amplitude difference over posterior scalp sites around 400 msec from the onset of the gender-marked syllable (i.e., -o/-a).

This late positivity is generally taken to be a P600 component (e.g., Osterhout & Mobley, 1995), alternatively named a syntactic positive shift (SPS) (Hagoort, Brown, & Groothusen, 1993; Neville, Nicol, Barss, Forster, & Garrett, 1991), peaking over the back of the head around 600 msec after violation/mismatch onset. It has been interpreted by some as an index of processing a violation specific to a syntactic stage of reanalysis (e.g., Gunter et al., 2000; Osterhout & Mobley, 1995; Hagoort et al., 1993), although a violation is not necessary for P600 elicitation (e.g., Coulson & Van Petten, 2002). Other researchers have espoused a more domain-general view, and taken the P600 as an index of the recognition of a task-related anomaly (e.g., Coulson, King, & Kutas, 1998; Patel, Gibson, Ratner, Besson, & Holcomb, 1998). Whatever process the P600 reflects, it was not observed by Wicha, Bates, et al. (2003) and Wicha, Moreno, et al. (2003) to gender agreement violations between an article and a line drawing depicting an object. Instead the ERPs to pictures replacing nouns within written or spoken Spanish sentences, whose referents mismatched in gender with a preceding gender-marked article, were characterized by an increased negativity between 500 and 700 msec postpicture onset relative to those of matching gender. It is unclear why words and pictures yield different polarity effects. Given that grammatical gender is a property of words and not an inherent property of depicted inanimate objects (e.g., a basket is neither masculine nor feminine, per se), the fact that gender (dis)agreement affects the brain's processing of line drawings at all indicates that information about the gender of the depicted noun was accessed although the word was never presented. The grammatical gender of the target noun might be accessed from sentential context and/or the conceptual representation of that noun, in turn, gender might affect semantic level integration of a noun into a sentence context.

In fact, some evidence suggests that gender agreement and semantic congruity interact during sentence comprehension (e.g., Hagoort, 2003; Wicha, 2002; Wicha et al., in press; Gunter et al., 2000; Bentrovato, Devescovi, D'Amico, & Bates, 1999; Bentrovato, Devescovi, D'Amico, Wicha, & Bates, 2003), although it is not clear just how early in processing this interaction occurs. Gunter et al. (2000), for example, observed an interaction on the magnitude of the late positive component (LPC or P600) to nouns, with a larger LPC to gender-disagreeing than gender-agreeing nouns, which was in turn larger and earlier in high- than low-constraint sentences in German. In contrast, only semantic fit affected the N400 to the target word; the normal response to any potentially meaningful word (written, spoken, or signed) or picture (e.g., Kutas & Hillyard, 1983; Kutas, Neville, & Holcomb, 1987). As expected, N400 amplitude increased as the noun's semantic fit within the sentence decreased, but it was not affected by gender (dis)agreement. Instead, a left frontal negativity (LAN) between 350 and 450 msec was observed to gender-disagreeing nouns, in both high- and low-constraint sentences. In Gunter et al.'s study then, gender agreement and semantic information from sentential context interacted only in the later time window of the LPC, but not during the earlier N400 or LAN window. The authors interpreted these results to indicate that gender and semantic information interact only during a final stage of reprocessing (as reflected in the P600) and not during initial stages of syntactic or semantic integration (as reflected in the LAN and N400, respectively).

In contrast, a few studies have shown that the N400 is sensitive to grammatical agreement violations, specifically as an interaction between gender and semantic variables (e.g., Deutsch & Bentin, 2001; Hagoort & Brown, 1999; see also Kutas, Federmeier, Coulson, King, & Muente, 2000, for a review on language and ERPs), while others have shown no interaction at any point in the ERPs when using pictures instead of words (Wicha, Bates, et al., 2003; Wicha, Moreno, et al., 2003). Hence, an important part of the current study is aimed at examining the ERP activity at target gender-marked nouns in Spanish sentences, like the Red Riding Hood example, to determine if and when gender agreement and semantic fit interact during sentence comprehension. First, we determine whether a P600 is elicited in response to grammatical gender violations on words. Then, similar to Gunter et al. (2000), we expect to find an interaction between gender agreement and semantic fit on LPC amplitude. In addition, if gender can affect semantic integration of the word into the sentence context we also expect to observe an earlier interaction between these two factors on the N400 component.

Do Readers Predict?

Another equally important aspect of the current study focuses on testing the hypothesis that individuals use sentence context to generate expectations for nouns and their associated articles during language processing. Most ERP studies of gender agreement have assessed the brain activity at the point at which the agreement violation becomes obvious, for example, at the noun but not at its preceding gender-marked article. However, Wicha, Bates, et al. (2003) and Wicha, Moreno, et al. (2003) observed an additional effect of gender “agreement” (in this case, between the gender expected from prior context and that of the presented article) or gender expectancy, before the overt agreement violation at the noun. Sentences were always grammatically and semantically plausible up to the article, given that an article of either gender was a possible continuation of the sentence (e.g., una canasta vs. un costal). However, the article preceding the target noun had either the appropriate (e.g., una) or inappropriate (e.g., un) gender relative to what was expected based on prior sentence context (e.g., canasta), as determined from cloze probability norming of these materials. Defined in this way, articles of unexpected gender elicited an N400-like component, a widely distributed increased negativity between 300 and 500 msec post article onset, compared with articles with contextually expected gender. We interpreted this finding to indicate that listeners and readers do form expectations (whether consciously or not) about upcoming words based on the preceding context, and that these expectations are specific enough to include information about the gender of the expected noun and its associated article. The nature of the effect—an enhanced negativity (N400) instead of an enhanced positivity (P600)—suggested to us that the “violation” of the expected gender at the article is more likely to be at a semantic than syntactic level, keeping in mind that the target nouns in these studies were depicted by line drawings. We expand upon this finding in the current study by assessing the ERP activity to the article preceding a target noun, now a written word. Again, one of our primary aims is to determine if individuals create expectations about upcoming nouns during reading comprehension. If we find that they do, then we aim to determine whether the gender information at the article is processed primarily at a semantic level, as in previous studies using picture targets.

RESULTS

Behavior

Performance on the off-line sentence recognition test was well above chance (i.e., 33%), with mean overall accuracy for classifying sentences at 71% (range 43–100%). The more challenging items were those similar to experimental sentences, accounting for 51% of total errors committed. On average, participants rarely misclassified identical or new sentences (0.08 and 0.06 of data, respectively), confirming that participants were attending to the sentences during the electroencephalogram (EEG) recording.

Event-Related Brain Potentials

Analyses are reported for the target noun and article, analyzed separately each relative to its own 100-msec prestimulus baseline, unless otherwise noted. Overall, the ERP to each word is characterized by early sensory components—N1 and P2 over frontal sites and P1, N1, and P2 over posterior sites—followed by a slower negative component (N400 region) for both the article and noun, as well as a later positivity (LPC) for the noun. Effects for repeated measures with greater than one degree of freedom are reported after Huynh–Feldt correction.

Target Noun Analyses

Mean amplitude of ERPs to the nouns were subjected to ANOVAs with 2 levels of semantic congruity (congruent and incongruent), 2 levels of gender agreement (article–noun match and mismatch), and 26 levels of electrode for two time windows, one between 300 and 500 msec encompassing the region of the N400 and a second between 500 and 900 msec poststimulus onset encompassing the region of the LPC or P600. To determine onset and duration of significance for each effect, additional analyses of 25-msec intervals were conducted within these main time windows.

Semantic Congruity

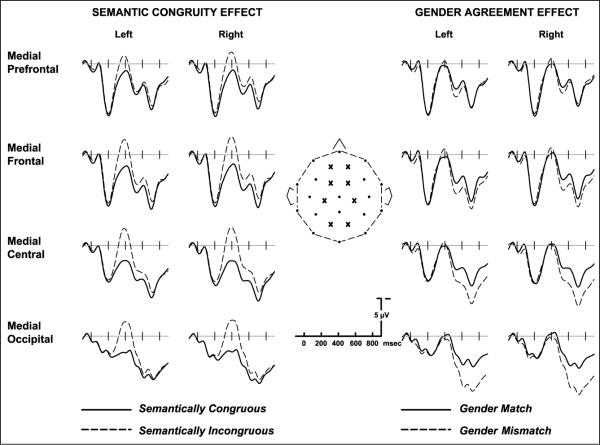

Representative ERPs to the semantically congruent and incongruent target nouns collapsed across gender agreement, from electrodes going from front to back along the middle of the head, are shown in the left half of Figure 1. As expected, semantic congruity had a large effect, with a relatively greater negativity (i.e., larger N400) to incongruent than congruent nouns between 300 and 500 msec [main effect of congruity, F(1,27) = 56.80, p < .00001]. A significant congruity by electrode interaction effect, F(25,675) = 22.22, p < .00001, confirms the typical distribution of an N400 effect for words, broadly distributed and largest over central and parietal electrodes over right hemisphere sites. Additional analyses indicate that both the main effect of semantic congruity and its interaction with electrode site are reliable as early as 250 msec post noun onset up through 700 and 800 msec, respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative grand average ERPs from eight electrode sites (indicated by the X's on the schematic head) from front to the back of the head to the noun targets. On this and all subsequent figures, negative is plotted upward and time is represented on the x-axis in milliseconds. The left half of the figure shows the effect of semantic congruity; overlapped is the ERP to nouns that made sense in the sentence context (solid line) versus the ERP to those that did not (dashed line). Note greater negativity to the incongruous nouns relative to the congruous ones from 200 msec throughout the recording epoch. The right half of the figure shows the effect of gender agreement between the article and noun; overlapped is the response to nouns when it agrees in gender with that of the prior article (solid) versus when it does not (dashed line). Note that gender mismatches are associated with a greater positivity from 400 msec throughout the recording epoch.

Gender Agreement

The right half of Figure 1 shows representative ERPs to the target noun at the same electrode sites, now as a function of article–noun gender match or mismatch, collapsed across semantic congruity. The effect of gender mismatch on the noun starts slightly later than the effect of semantic congruity and is of opposite polarity. There was no main effect of gender congruity between 300 and 500 msec, F(1,27) = 0.61, p < .44, but the interaction between gender agreement and electrode site was significant, F(25,675) = 2.45, p < .037, with an enhanced positivity for gender mismatches, maximal over medial posterior sites of the right hemisphere. Between 500 and 900 msec, gender mismatches were significantly more positive than matches, F(1,27) = 19.13, p < .0002, and gender agreement interacted significantly with recording site, F(25,675) = 17.06, p < .00001. Typical of a P600 effect to words, the gender (dis)agreement effect was most pronounced over medial posterior recording sites and slightly larger over the right hemisphere. There is also a significant difference between 0 and 100 msec, where the response to gender mismatches was more positive than matches (p < .006), reflecting the overlap with the response to the preceding article (500–700 msec post article onset; see below). The interaction with electrode site was reliable as early as 375 msec post noun onset (p < .0001) through the end of the recording epoch.

Gender by Semantic Interaction

The interaction between semantic congruity and gender agreement was marginally significant during the N400 measurement window (300–500 msec), F(1,27) = 3.58, p < .069, and statistically significant during the P600 measurement window (500–900 msec), F(1,27) = 24.50, p < .00001. Finer-grained analyses indicate that this interaction was reliable as early as 450 msec post noun onset (p < .004) and lasted throughout the recording epoch (~900 msec). A significant three-way interaction (illustrated in Figure 2) among semantic congruity, gender agreement, and electrode site occurred as early as 450 msec (p < .044) to the end of the recording epoch [(300–500 msec), F(25,675) = 2.23, p < .072, and 500–900 msec, F(25,675) = 5.27, p < .001]. In the region of the N400, gender agreement violations elicit a small negativity above and beyond that to the semantic violations alone, readily visible in the left half of Figure 3 for semantically incongruous nouns over left frontal sites, as well as the beginning of an LPC greatest over posterior sites on the right. In the region of the P600, gender agreement elicited an enhanced positivity maximal over posterior electrode sites, which appears to be greater for congruous than incongruous nouns.

Figure 2.

Grand average ERPs to target nouns from all 26 electrode sites (looking down on top of the head) with the four experimental conditions overlapped. Note the bilateral distribution of the increased frontal negativity to the double violation condition (semantic and gender violations) compared with the semantic violation alone, as well as the LPC distribution over posterior sites for all violations relative to the control (semantically congruous and gender matching). The two highlighted electrodes (left medial frontal and left medial occipital) appear enlarged in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Grand average ERPs to target nouns for the 4 experimental conditions overlapped, shown at an anterior and a posterior site relative to two different baselines. On the left, relative to a 100-msec prestimulus baseline, the largest negativity in the N400 region is elicited by the double violation at the anterior site, while the beginning of the LPC is visible at the posterior site. In the LPC/P600 region, the interaction differs at anterior and posterior sites, but relative to the prestimulus baseline, the positivity is largest for gender-mismatching semantically congruous nouns. On the right, the same data are baselined on the peak of the N400 (i.e., peak-to-peak comparison), thereby taking into account differences in N400 amplitude across conditions. In contrast to the prestimulus baseline comparison, measured peak-to-peak, it is the double violation that elicits the largest positivity in the LPC/P600 region; there was no significant difference between the semantic-violation and gender-violation conditions nor any interaction between the two.

This interaction can also be seen in the difference ERPs. The left half of Figure 4 shows that the effect of semantic congruity (incongruous minus congruous ERPs) is greater (deviates further from baseline) when the article and noun mismatch in gender (difference between ERPs in dotted lines in Figure 3) than when they match (difference between ERPs in solid lines in Figure 3), starting at ~400–450 msec. This difference reflects greater positivity to gender violations alone posteriorly and greater negativity to double violations frontally. The right half of Figure 4 shows that the effect of gender agreement (mismatch minus match ERPs) is greater when the picture is semantically congruous with the preceding sentence context (ERPs to light-dotted minus dark-solid lines in Figure 3) than when it is not (ERPs to dark-dotted minus light-solid lines in Figure 3), starting at ~400–450 msec. None of the early differences in these difference ERPs are statistically reliable.

Figure 4.

Difference ERPs at 8 electrodes indicated from front to back on the schematic head illustrate the interaction between semantic congruity and gender agreement relative to a prestimulus baseline. The left half of the figure shows that the effect of semantic congruity violations (incongruous minus congruous ERPs) is greater when the noun also mismatches in gender with the preceding article (dashed line, which corresponds to the difference between the dotted lines in the left half of Figure 3) than when it matches (solid line, which corresponds to the difference between the solid lines in Figure 3). In the N400 time window, the congruity effect (incongruous minus congruous) is characterized by relatively greater negativity for gender mismatches relative to gender matches across the scalp; this widespread negativity of the congruity effect for gender mismatches versus matches arises from the contribution of the greater frontal negativity to incongruous gender mismatches and the greater positivity to congruous gender mismatches. The right half of this figure shows that the effect of gender agreement (mismatch minus match) is greater when the noun fits (solid line, corresponding to the difference between dark-solid and light-dotted lines in left half of Figure 3) than when it does not fit with the meaning of the sentence context (dashed line, corresponding to the difference between light-solid and dark-dotted lines in Figure 3). None of the small differences in these difference ERP waveforms is reliable.

Peak-to-Peak Analyses

Gender agreement and semantic congruity interacted in both measurement windows when measured relative to the prestimulus baseline. However, visual inspection of the ERP waveforms across the scalp suggests that the N400 and P600 components overlap in time, signifying that independent analyses of the two measurement windows may be misleading. In particular, measurement of P600 amplitude relative to baseline ignores the fact that the positivity begins at different points in the second measurement window depending on whether the target noun was semantically congruous or incongruous. One way to address this concern is via peak-to-peak measurements (in this case between peak negativity in the N400 region and peak positivity in the P600 region). Peak-to-peak analyses thus were conducted using all 26 scalp electrodes and a measurement window from 300 to 900 msec post noun onset, encompassing the amplitude difference between the maximum negative peak and maximum positive peak in that interval. This is analogous to aligning (baseline) the data at the N400 peak to the noun, as illustrated in the right half of Figure 3.

This measurement revealed a main effect of gender agreement, F(1,27) = 10.40, p < .003, where gender mismatches had larger peak-to-peak amplitude than matches, and a main effect of semantic congruity, F(1,27) = 36.42, p < .00001, where semantically incongruous nouns had larger peak-to-peak amplitude than congruous ones. There was no interaction between gender agreement and semantic congruity, F(1,27) = 0.25, p < .62. There were significant interactions between gender agreement and electrode, F(25,675) = 6.30, p < .0001, and semantic congruity and electrode, F(25,675) = 16.01, p < .00001, but no three-way interaction, F(25,675) = 1.34, p < .24. The effect of semantic congruity was slightly larger over the left than right hemisphere. The effect of gender agreement was bilaterally symmetric. Both gender agreement and semantic congruity had maximal peak-to-peak amplitudes over medial, posterior electrodes. All pairwise comparisons across conditions were significant (p < .01 and p < .03 for the gender-agreement effect vs. the double effect), except for the pure-gender mismatch versus pure-semantic violation conditions (p = .12), indicating that the LPC increased equally in size for both types of violation relative to their respective N400 amplitudes.

Finally, although there was no interaction in the peak-to-peak comparison across conditions, a post hoc comparison of the difference ERPs shows that the effect of double violations (gender-mismatching, semantically incongruous minus gender-matching, congruous) was significantly smaller than the algebraically summed effects of semantic congruity (semantic-violation condition minus gender-matching, congruous) plus gender agreement (gender-violation condition minus gender-matching, congruous), both in mean amplitude between 500 and 900 msec when measured relative to prestimulus baseline (double = 0.69 μV vs. sum = 2.87 μV; p < .00001) and when measured peak-to-peak (double = 8.38 μV vs. sum = 13.37; p < .00001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Difference ERPs from four midline electrodes (MiPf, MiCe, MiPa, and MiOc) from front to back of the head comparing the double-violation effect (solid line in all three columns: gender-mismatching-semantically incongruous minus matching-congruous ERPs) to the pure effects of semantic congruity (left column: gender matching, semantic incongruous minus congruous) and gender agreement (middle column: semantically congruous, gender-mismatching minus matching). The right column shows that the sum of the effects of pure gender agreement and pure semantic congruity violations does not equal the brain's response to the double violations (two violations presented together).

Preceding Article Analyses

To determine if the article was expected based on the meaning of the sentence context, we subjected the mean amplitude of the ERPs to an ANOVA with two levels of gender expectancy (expected and unexpected gender) and 26 levels of electrode, between 300 and 500 msec (encompassing the N400 region) and between 500 and 700 msec (encompassing the P600 region) post article onset. Expected gender was defined as the gender corresponding to the noun with the highest cloze probability within any given sentence, based on the cloze procedures described in the method section. For example, if corona is the expected noun, an article of feminine gender (una) would be expected while a masculine article (un) would be unexpected.

The main effect of expectancy was significant between 500 and 700 msec, F(1,27) = 8.03, p < .009 with a larger positivity for articles of unexpected than expected gender but was not significant between 300 and 500 msec, F(1,27) = 0.001, p < .94 (Figure 6). Additional analyses of 100-msec intervals revealed that this effect was not significant in any other time window (500–600 msec, p < .004; 600–700 msec, p < .037). The interaction between gender expectancy and electrode site was marginally significant between 500 and 700 msec, F(25,675) = 2.22, p < .065 [between 300 and 500, F(25,675) = 1.00, p < .41], being slightly larger over left than right hemisphere sites (this lack of an interaction with electrode site may be due to the small magnitude of the effect).

Figure 6.

Grand average ERPs from all 26 electrode sites (looking down on the top of the head) for the effect of gender expectancy at the article preceding the target noun. The effect is characterized by a widely distributed enhanced positivity for the contextually unexpected (dashed line) versus expected (solid line) articles between 500 and 700 msec (here shown only through 650 msec since the visual EP to the following word is too large to graph at this scale; see Figure 7 for the full two word waveforms). None of the smaller differences is reliable.

DISCUSSION

In essence, our results show that readers do attend to the grammatical gender of words, both articles and nouns, and process this information in real time during written sentence comprehension. As expected, a noun's semantic fit within the sentence context modulated N400 amplitude with a larger negativity followed by a larger posterior positivity for incongruous compared with congruous nouns. Gender agreement between a noun and its preceding article modulated the amplitude of both the late positivity and the N400 in interaction with semantic congruity. Moreover, in agreement with our previous findings, the pattern of ERPs elicited by the article preceding the noun seemed to reflect whether the article's gender was expected based on the ongoing sentence context. This effect of gender expectancy was characterized by a widely distributed positivity, in contrast to the increased negativity we observed in previous studies when the same target was depicted via a line drawing.

Appreciation of Grammatical Gender Agreement

Gender agreement violations using words have generally been associated with a late positivity (P600) over posterior recording sites, interpreted as either indexing syntactic reanalysis or, more generally, recognition of an (agreement) mismatch. On either interpretation, in many cases, it is the brain's analysis of a violation that elicits the larger positivity. Consistent with previous findings, gender-mismatching nouns in the current study, both alone and in combination with semantic violations, elicited a widely distributed increased positivity, maximal over medial posterior sites between 500 and 900 msec post noun onset—a P600. Although it says little about the functional interpretation of the P600, this finding confirms the brain's sensitivity to violations of grammatical gender agreement between words. Gender agreement, however, modulated P600 amplitude differently for semantically congruous and incongruous nouns, with double violations eliciting a smaller LPC than “pure” gender mismatches, at least when measured relative to a prestimulus baseline. This indicates that gender and semantic levels of processing are not necessarily independent in this time window.

Gunter et al. (2000) conducted a study similar in design to ours that also examined the interaction of grammatical gender and semantic fit. They manipulated gender agreement between an article-noun pair in written German sentences (always the first noun phrase of two), together with sentence constraint for the noun based on its relation to the preceding verb (e.g., “Sie bereist/befährt das/den Land…”—“She travels/drives the [neuter]/[masc] land [neuter]…”). They too obtained an interaction between sentence constraint and gender agreement on the P600 measured relative to a prestimulus baseline, with an earlier and larger positivity to nouns that mismatched in gender with the preceding article in high- compared with low-constraint sentences. Under the assumption that participants' primary goal was to extract meaning, they concluded that the reduction and delay in the P6—which they view as an index of syntactic repair—was a consequence of the greater semantic demands made by low- as opposed to high-constraint sentences.

By contrast, Hagoort (2003) in a design also similar to ours reported no interaction between semantic fit and agreement on the P600 and took this to mean that the P600 indexes a purely syntactic-level process; in their case P600 was measured relative to the prior N400 (i.e., peak-to-peak). More specifically, Hagoort manipulated the gender or number agreement in Dutch between an article and noun, and the semantic relationship between an intervening adjective and the noun. The target noun could appear either at the beginning or end of a written sentence (e.g., “De/Het kapotte/eerlijke paraplu staat in de garage”—“The [com]/The [neu] broken/honest umbrella [com] is in the garage” or “Cindy sliep slecht vanwege de/het griezelige/bewolkte droom”—“Cindy slept badly due to the [com]/the [neu] scary/sniffing dream[com]”). Semantic violations between the adjective and noun elicited larger N400 amplitudes than did agreement violations. In an attempt to take this difference in potential prior to the P600 into account, he measured P600 peak amplitude relative to an immediately preceding 200-msec interval (300–500 msec post-stimulus onset)—essentially the N400 peak—rather than relative to the more traditional prenoun baseline. By this measure, Hagoort obtained a main effect of syntactic agreement (including both gender and number agreement violations), but no effect of semantic congruity and no interaction between the two factors on the LPC/P600 for either sentence position. Hagoort interpreted this lack of an interaction to indicate that the P600 reflects brain activity related strictly to syntactic analysis and that assigning the syntactic structure of a sentence is independent of its semantic context. Like Hagoort, we also find that when the LPC/P600 is measured relative to the peak of the N400, the interaction between gender agreement and semantic congruity is not significant.

However, as noted above, when the late positivity is measured relative to the prestimulus baseline, we obtain a pattern supporting a different conclusion, more similar to Gunter et al. (2000); gender agreement and semantic congruity interact such that the LPC/P600 to double violations is smaller than that to gender violations alone. It is worth noting that this same pattern is visible in Hagoort's data, although measurements relative to prestimulus baseline were not reported.

It is impossible to know which of these analyses (baseline-to-peak or peak-to-peak) reveals the “true” data pattern; we have presented both. We do note, however, that the comparison depicted in our Figure 5 shows that the “pure” effects of semantic congruity and gender agreement do not sum to the effect of double violations (p < .0001), suggesting that there might be an interaction at the LPC/P600 after all, even on a peak-to-peak analysis.

Additionally, we found that both semantic congruity and gender agreement modulated LPC/P600 amplitude (measured peak-to-peak) equally, suggesting that semantic information can influence this component. While this is at odds with Hagoort's (2003) results, there are enough methodological differences between their experiment and ours to account for this inconsistency. Hagoort, for example, manipulated the two words prior to the noun; we varied only the immediately preceding article. Depending on reader's expectations, then, in Hagoort's study brain activity prior to the noun could have been influenced by both syntactic and semantic constraints, whereas in our study, only the grammatical gender of the article could directly influence activity prior to the noun. Moreover, in the Hagoort study, semantic anomalies were created by an adjective that modified the target noun incongruously, although the noun itself always fit the sentence context; in ours, the semantically anomalous nouns never fit with the preceding sentence context. It would not be surprising, therefore, if our participants reacted more strongly to the more patent anomaly, incongruous with the more global-message level, with a larger LPC. Finally, Hagoort's participants were asked to make an acceptability judgment at the end of each sentence; ours read for comprehension. This methodological difference may have interacted with the fact that Hagoort employed different types of “syntactic” violations (only some of which were of grammatical gender), in addition to the semantic violations. It is impossible to guess what the subjective probability of each violation type was for Hagoort's participants. However, given that the P600 has been shown to be sensitive to task demands, and in some cases, to the probability of occurrence of task-related stimuli (e.g., Coulson et al., 1998), these factors also may have affected the P600 to the syntactic and semantic violations in a manner not easily known, but likely differently from our study, which included only one type of syntactic violation.

In any case, differences notwithstanding, the overall pattern of the major effects is rather similar between Hagoort's and our results, on one hand, and between Gunter et al's and our results, on the other. In sum, it appears that readers' brains are sensitive to agreement violations between articles and nouns, and that the processing of these agreement violations is affected by the semantic fit of nouns in sentences, at least when measured relative to a prestimulus baseline. At present, we cannot rule out the possibility that the P600 is sensitive to both syntactic- and semantic-level processes, and that these might interact during some relatively late stage of processing.

Gender Agreement Affects Semantic Integration

Our results indicate that gender can influence the integration of a noun into a sentence context at a semantic level. Grammatical gender modulated the ERP in the N400 time window in two ways. First, the P600 over posterior sites started as early as 375 msec, thereby overlapping the N400 component at certain recording sites. Second, gender interacted with semantic fit, leading to a larger N400 for double violations than semantic violations alone, showing that gender agreement can modulate N400 amplitude, at least when a noun is semantically anomalous.

A handful of other studies have shown an effect of gender agreement on the N400, generally in interaction with a semantic variable (e.g., Wicha, Bates, et al., 2003; Wicha, Moreno, et al., 2003; Deutsch & Bentin, 2001; Hagoort & Brown, 1999; Hagoort, 2003). For instance, in Hebrew—a language in which verbs also have gender, Deutsch and Bentin (2001) found, in addition to both P600 and LAN effects, a larger N400 to verbs mismatching in gender with a preceding animate noun than to gender matching verbs. However, agreement did not affect the N400 to verbs modifying inanimate nouns (contrary to our findings), where gender is purely syntactic. Similarly, Hagoort and Brown (1999) manipulated gender agreement between article and noun pairs in Dutch sentences. All gender-mismatching nouns elicited a P600 effect, although those occurring in sentence final position also elicited an enhanced N400, which the authors attributed to sentence wrap-up effects. In these two studies, the effect of gender-semantic interactions was evidenced by comparing different words (e.g., animate vs. inanimate; beginning or end of sentence). In our study, gender and semantic variables were found to interact on the N400 to the same word across different conditions, similar to Hagoort's (2003) findings.

In Hagoort's (2003) study, both semantic and agreement (gender and number combined) violations elicited significantly larger N400s than their nonviolation counterparts for nouns in both mid and final sentence positions, indicating that agreement can impact semantic integration. We did not find a main effect of agreement on the amplitude of the N400, perhaps because of the overlap of the late positivity elicited by agreement violations in this window, at least at posterior sites. Similar to our data, the ERPs to the double violations on nouns that appeared near the beginning of sentences in Hagoort's study were characterized by larger N400 amplitude than pure semantic violations (e.g., a “syntactic boost”). Although this negativity could potentially be an independent component such as a LAN, because of the overlap and distribution of the N400 and P600 effects, we believe this negativity to gender mismatches is an enhancement of the N400 peak rather than a separate component. There are studies, however, that have not observed an effect of gender on the N400 (e.g., Brown et al., 2000; van Berkum et al., 1999), or that observed instead a LAN to agreement violations (e.g., Gunter et al., 2000; Demestre et al., 1999).

In particular, Gunter et al. (2000) reported a main effect of sentence constraint on N400 amplitude—with greater negativity for low than high cloze nouns—which, contrary to Hagoort's and our findings, was unaffected by gender agreement. They did, however, observe a LAN to gender mismatches between 350 and 450 msec—a LAN—and attributed it to an independent “syntactic processor” (note that prefrontal and occipital sites were not included in this analysis, and that this measurement window encompasses the N400). Note that the positivity (a P600) that Gunter et al. observed to gender agreement violations in high-constraint sentences began as early as 450 msec, particularly over posterior sites, and in low-constraint sentences as late as 700 msec. We found a similar pattern of results in that our semantically congruous nouns were affected by gender agreement as early as 375 msec post noun onset, whereas the semantic anomalies (equivalent to very low-cloze nouns) show an effect of gender agreement as late as 500 msec. As in our data, the N400 and posterior positivity (P600) to gender agreement violations overlap in time. Hence, the LAN in Gunter et al.'s study might perhaps be the result of adding a widely distributed N400 with a slight right bias and a posteriorly distributed P600, yielding a negativity clearly visible only over sites with the least overlap—namely, left frontal electrodes.

In sum, both Hagoort's (2003) and our data show that gender agreement and semantic congruity interact early in word processing to influence semantic integration of the noun into the sentence. Specifically, we both observed a larger N400 for double violations than semantic violations alone, albeit apparently more frontal in our data. This difference in distribution in the N400 time window between the two studies seems to be due to the earlier latency of the posterior P600 in our study relative to that of Hagoort's study, such that the N400 and P600 overlap in our data, whereas they do not in his. In contrast, Gunter et al. reported no effect of gender on the N400, but did report a LAN; note that aside from their label, these may be similar effects. Overall, gender agreement appears to influence semantic integration of a noun, presumably making it more difficult to integrate when it mismatches in gender with its preceding article, at least when the word is also semantically incongruous.

Anticipating Words and Their Gender

Lastly, we turn to the on-line anticipation of the target noun and its preceding article. As in our previous studies, we found a significant effect of gender expectancy at the article prior to the target noun (Wicha, Bates, et al., 2003; Wicha, Moreno, et al., 2003). Recall that these sentences are neither semantically incongruous nor grammatically incorrect upon appearance of an article of either gender (expected or unexpected), since the sentences could plausibly have continued with a gender-matching noun even after an unexpected article. It is our contention, therefore, that the gender expectancy effect observed at the article can only be due to a violation of an expectation based on the ongoing context and not to an overt gender violation per se. We take this to mean that readers are using sentence context (meaning and syntactic structure) to anticipate upcoming nouns, including information about their gender, a morphosyntactic property of words in Spanish. Presumably, this anticipatory behavior aids in the integration of information, by either speeding up processing or facilitating the construction of meaning of congruous sentences. This same mechanism also could slow processing when an expectation is not met, as has been observed in some behavioral studies (e.g., Bentrovato et al., 2003; Wicha et al., in press). Moreover, this antici patory behavior is likely to be modulated by contextual constraint, with stronger predictions (and ultimately larger effects from an expectancy violation) for items in highly than lowly constraining contexts. In the current study, the contextual constraint/cloze probability for the target nouns was high (.65–1). In post hoc analysis of the data of Wicha, Bates, et al. (2003), in which the contextual constraint/cloze range was greater (.4–1), there was a significant difference in the expectancy effect at the article that was larger for high than low-cloze items. We believe this indicates that although the brain makes (probabilistic) predictions about each upcoming word in a sentence, some contexts clearly allow more precise predictions than others (e.g., first vs. second noun phrase).

Note that in our previous studies, the articles (written or spoken) preceding gender-mismatching line drawings elicited an N400-like negativity, in contrast to the widely distributed positivity between 500 and 700 msec observed in this study. This difference cannot be ex plained by the article per se, because the written sentences in Wicha, Moreno et al. (2003) were identical to the ones used herein, except that the targets here were words; in the previous one, they were line drawings. It is noteworthy, although possibly coincidental, that within each study the polarity of the effects of gender agreement at the noun and of gender expectancy at the article were the same—both were negative for sentences with embedded line drawings and positive for words (see Figure 7). Gender agreement violations at the drawings elicited a negativity, albeit small, in the region of the P600; the scalp distribution was more frontal and biased toward the left hemisphere than the current results. Thus, although the timing of gender agreement processing appears to be similar for words and pictures, the nature of the processes involved appears to be more distinct. Although the current study was not designed to address processing differences between words and pictures, we will highlight some potential reasons for this polarity difference in the agreement effects, which must somehow be due to target modality—picture versus word—and/or the processing requirements that each entails (e.g., processing rebus vs. normal sentences).

Figure 7.

Comparison across four midline electrodes from front to back of the head of the main effect of gender agreement collapsed across semantic congruity for a three-word time window (one word every 500 msec), including the target article and noun in the current study (far left) and target article and picture (middle) embedded in written sentences (presented one word at a time in Wicha et al.'s, 2003, study). On the far right, the difference ERPs (gender mismatch minus match) across experiments are compared. The effects across the two experiments have a similar time course, but differ in polarity at both the article (onset at 0 msec) and target noun/picture (onset at 500 msec).

Pictures do not have grammatical gender (e.g., basket), since gender is a property of words. Moreover, they lack the overt morphological markings that characterize written and spoken words, particularly in Spanish where gender markings on nouns are often clearly and consistently marked (99.9% of nouns ending in “-o” are masculine while 96.3% ending in “-a” are feminine (Teschner & Russell, 1984)). Thus, gender agreement violations could easily be determined simply by matching overt gender-marked morphemes on articles (e.g., un, una, el, la) and nouns, but not pictures. ERP data supporting this idea come from Deutsch and Bentin (2001) who found (among other effects) that gender-agreement violations between Hebrew nouns and verbs elicited a P600, but only for marked predicates (i.e., plural verbs displaying gender morphology) and not for unmarked predicates. Since a morphosyntactic match between an article and picture cannot be performed directly, either the lexical equivalent is automatically accessed during picture processing, or the concept and lexical equivalent are activated by prior context, and in turn matched with the picture. Otherwise, we would not have observed a gender mismatch at the picture in our previous studies. We believe that it is likely that participants analyzed the sentences with embedded pictures primarily at a semantic level, as indicated by the N400-like effect on both articles and pictures. Thus, it may be that morphosyntactic features are somehow encoded or linked to semantic level information. Incidentally, the extent to which pictures and words share a common representation in the brain is a matter of long-standing debate (see Federmeier & Kutas, 2001, for a comprehensive discussion), some propose separate processing systems for pictures and words, wherein both conceptual and lexical representations are stored (e.g., dual-coding models, Paivio, 1991; Shallice, 1988), while others propose a shared semantic representation, with lexical level information, such as gender, accessed directly only by words and not pictures (e.g., single code models, Potter, 1986). In this regard, our previous data indicate that grammatical gender information is accessed at least indirectly via pictorial representations.

In conclusion, semantic congruity influenced the integration of a noun into a sentence context, eliciting an N400 to semantic anomalies. Gender agreement violations at the noun enhanced the amplitude of the N400 and elicited a posterior P600 as well. In the N400 region, gender agreement and semantic congruity interacted at certain recording sites, with a larger negativity visible over frontal sites for double violations, and the beginning of an LPC/P600 to gender agreement violations visible over posterior sites. In the P600 region, there appears to be an interaction between gender agreement and semantic congruity when measured relative to the prestimulus baseline, with a larger P600 for semantically congruous than incongruous nouns. Using a peak-to-peak measurement, however, the P600 appears to be of the same size for congruous and incongruous items, or perhaps slightly larger for double violations. Furthermore, unexpected articles elicited an enhanced positivity between 500 and 700 msec post article onset relative to expected articles, demonstrating that readers do have expectations about upcoming words based on the ongoing sentence context, and that these expectations are specific enough to include information about the expected word's grammatical gender. Finally, differences between our current findings and those obtained from line drawings hint at the processes involved in building expectations, accessing lexical information and integrating words into preceding sentence context during online comprehension. In sum, our data demonstrate that readers attend to the gender of words, both for articles and nouns, and use this information in real time sentence comprehension, albeit differently when gender markings are overt, as on words, than when they are covert, as for their picture referents (Wicha, Bates, et al., 2003; Wicha, Moreno, et al., 2003).

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-eight right-handed, native speakers of Spanish (24 women, mean age 21.4 years, ranging between 18 and 31 years; 4 men, mean age 20.8 years, ranging between 18 and 23 years), residents of Baja California, Mexico, and students at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) in Tijuana, received $24 for one 3-hour session of testing at the University of California at San Diego. Handedness and language dominance were assessed via a self-rating questionnaire. All participants were exposed to Spanish from birth and used Spanish on a daily basis, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and reported no physical or cognitive disabilities that would interfere with the reading-comprehension task.

Electroencephalogram Recording Parameters and Data Analysis

The EEG was recorded from 26 tin electrodes embedded in a standard electro-cap, each referenced on-line to the left mastoid. Blinks and eye movements were monitored through a bipolar recording from electrodes placed on the outer canthi of each eye and under each eye (referenced to the left mastoid). Electrode impedances were maintained below 5 Ω. The EEG was amplified with Grass amplifiers with band pass set from 0.01 to 100 Hz and sampled at a rate of 250 Hz. Trials with artifacts due to eye movements, excessive muscle activity, or amplifier blocking were eliminated off-line before averaging—approximately 5% of the data for each the target article and noun (with roughly equal loss of data across conditions). For subjects with excessive blinks (10% or more), the data were corrected using a spatial filter algorithm (Dale, 1994). Data were re-referenced to the algebraic sum of the left and right mastoids and averaged for each experimental condition, time locked to the onset of the critical article and noun. A digital bandpass filter set from 0.1 to 10 Hz was used on all of the data prior to running analyses to reduce high frequency content, irrelevant to the components of interest.

Procedure

The stimuli consisted of sentence pairs, visually presented in black type on a white background, in Spanish with appropriate accents. A target noun appeared always immediately following a gender-marked determiner (i.e., el, la, un, una, las, los) anywhere in either the first or second sentence, but never sentence final to avoid sentence wrap-up effects (although it could appear at clause boundaries, and was in some cases followed only by an adjective before the sentence terminated). This design by Wicha et al. (in press) was originally used with spoken sentences, decreasing predictability of the target's position in the sentence. The sentence containing the target noun was presented one word at a time (300 msec on, 200 msec off) in the center of the monitor, preceded by a 1-sec fixation marker (“+++”); the other was presented whole to ease eye strain, with 1 sec interstimulus interval between sentences. Approximately half of the trials began with the target and half with the whole sentences, counterbalanced for order across participants.

Participants were seated in a dimly lit, sound-insulated booth approximately 3 feet from a color computer monitor. A practice session presented two examples of each experimental condition. Participants were instructed to read the sentences silently for comprehension and told that their recognition for these would be tested at the end of the experiment. They were asked to avoid blinking during the word-by-word sentences and to read the other sentence at their own pace, advancing to the next stimulus event by pressing a hand-held button. Blocks consisted of 33 or fewer sentence pairs, followed by a short break. At the end of the recording session, participants completed a 30-sentence recognition test, with 10 completely new sentences plus 10 slightly modified and 10 identical versions of previously presented filler sentences. Participants classify each sentence as identical, new, or similar.

Stimuli Preparation

Sentences were adapted from Wicha, Moreno et al. (2003) by replacing the target line drawing with its corresponding word referent. The 176 experimental sentences had previously been normed for contextual constraint (range 0.65–1.0, mean 0.80) by native Spanish speaking students at the UABC, who completed sentence fragments with an article–noun pair. An additional 88 congruous, grammatically correct sentences ranging from low to high constraint were used as filler items, for a total of 264 sentences per experimental list.

The target article and noun in each experimental sentence were manipulated, with either the highest expected noun or a semantically anomalous one of the same gender, and an article that either agreed or disagreed with the noun in gender, to create four conditions as follows (Spanish in italics with English gloss):

Gender match: semantically congruous —

El príncipe soñaba con tener el trono de su padre. El sabía que cuando su padre muriera podría al fin ponerse la corona por el resto de su vida.

The prince dreamt about having the throne of his father. He knew that when his father died he would finally be able to wear the [fem] crown [fem] for the rest of his life.

Gender match: semantically incongruous —

…podría al fin ponerse la maleta por el resto de su vida.

…he would finally be able to wear the [fem] suitcase [fem] for the rest of his life.

Gender mismatch: semantically congruous —

…podría al fin ponerse el corona por el resto de su vida.

…he would finally be able to wear the [masc] crown [fem] for the rest of his life.

Gender mismatch: semantically incongruous —

…podría al fin ponerse el maleta por el resto de su vida.

…he would finally be able to wear the [masc] suitcase [fem] for the rest of his life.

Note that the sentence pairs contained between 1 and 7 articles prior to the manipulated article, which varied in cloze probability, such that readers could not predict with certainty that a violation would occur after any particular article. To avoid confounding grammatical and semantic gender, only a small set of animals with names that remain constant across genders was used (e.g., cebra–zebra; pulpo–octopus); no targets referred to humans. Nouns referring to feminine objects that take a masculine article were not used as experimental items (e.g., el hacha–the [masc] ax [fem]), nor were nouns with a strong lexical competitor or synonym of opposite gender based on the norming study (e.g., ball–balón [masc]/pelota [fem]). Target nouns were matched in sets of four based on gender, number, animacy, word frequency (based on Alameda & Cuetos, 1995) and number of syllables, and were rotated once across the four corresponding experimental sentences to create the semantically incongruous conditions for each (see Appendix), making it unlikely for participants to predict an anomalous noun from having previously read a counter sentence. For each noun target and sentence to appear only once per list, the sets of four nouns appeared in the same experimental condition within the same randomly assigned list, with an equal number of stimuli per condition. The sentences were blocked by sentence type, target-first separate from target-second sentence pairs, so readers could know when to blink, then randomized once and presented in the same order across participants. Each participant saw only one of the four lists.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants HD22614 and AG08313 to M. K. Also, N. Y. Y. W. was supported by NIH/NIDCD DC00351, APA/MFP MH18882, and NIH/NIMH MH20002. NIH/NIDCD DC00216 to Elizabeth A. Bates supported preliminary work for this study. We thank Elizabeth A. Bates for her insight and support, Ron Ohst, Paul Krewski, and Robert Buffington for outstanding technical assistance, and Lourdes Gavaldón de Barreto, Guadalupe Bejarle Pano, and the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California-Tijuana, School of Humanities, for their collaboration.

APPENDIX: EXAMPLE SENTENCE SET IN SPANISH WITH ENGLISH GLOSS

La historia de Excalibur dice que el joven rey Arturo sacó de una gran roca una/un espada/cartera enorme y mágica. Con ella se convertiría en el rey más poderoso de Inglaterra.

The story of Excalibur says that the young King Arthur removed from a large stone a [fem]/a [masc] sword [fem]/wallet [fem]. With it, he became the most powerful king of England.

Mis papás quisieron cargar poco en su viaje. Pero con lo que llevaba mi madre de ropa no les cupo todo en la/el maleta/espada nueva.

My parents wanted to carry little on their trip. But with what my mother took in clothing, it did not all fit in the [fem]/the [masc] suitcase [fem]/sword [fem] (new).

El príncipe soñaba con tener el trono de su padre. El sabía que cuando su padre muriera sería rey y podría al fin ponerse la/el corona/maleta por el resto de su vida.

The prince dreamt about having the throne of his father. He knew that when his father died he would finally be able to wear the [fem]/the [masc] crown [fem]/suitcase [fem] for the rest of his life.

Esta mañana fui al banco a sacar dinero. Cuando abrími bolsa para guardar el dinero en la/el cartera/corona me di cuenta que no tenía mi chequera.

This morning I went to the bank to take out money. When I opened my purse to put the money in the [fem]/the [masc] wallet [fem]/crown [fem] I realized that I did not have my checkbook.

REFERENCES

- Alameda JR, Cuetos F. Diccionario de frecuencias de las unidades lingüísticas del castellano. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Oveido; Oveido: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrovato S, Devescovi A, D'Amico S, Bates E. Effect of grammatical gender and semantic context on lexical access in Italian. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1999;28:677–693. doi: 10.1023/a:1023273012220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentrovato S, Devescovi A, D'Amico S, Wicha N, Bates E. The effect of grammatical gender and semantic context on lexical access in Italian using a timed word-naming paradigm. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2003;32:417–430. doi: 10.1023/a:1024899513147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, van Berkum JJA, Hagoort P. Discourse before gender: An event-related brain potential study on the interplay of semantic and syntactic information during spoken language understanding. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29:53–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1005172406969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson S, King JW, Kutas M. Expect the unexpected: Event-related brain response to morphosyntactic violations. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1998;13:21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coulson S, Van Petten C. Conceptual integration and metaphor: An event-related potential study. Memory and Cognition. 2002;30:958–968. doi: 10.3758/bf03195780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of California-San Diego; La Jolla, CA: 1994. Source localization and spatial discriminant analysis of event-related potentials: Linear approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Demestre J, Meltzer S, Garcia-Albea JE, Vigil A. Identifying the null subject: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1999;28:293–312. doi: 10.1023/a:1023258215604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch A, Bentin S. Syntactic and semantic factors in processing gender agreement in Hebrew: Evidence from ERPs and eye movements. Journal of Memory and Language. 2001;45:200–224. [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier KD, Kutas M. Meaning and modality: Influences of context, semantic memory organization, and perceptual predictability on picture processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2001;27:202–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter TC, Friederici AD, Schriefers H. Syntactic gender and semantic expectancy: ERPs reveal early autonomy and late interaction. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:556–568. doi: 10.1162/089892900562336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P. Interplay between syntax and semantics during sentence comprehension: ERP effects of combining syntactic and semantic violations. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2003;15:883–899. doi: 10.1162/089892903322370807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Brown CM. Gender electrified: ERP evidence on the syntactic nature of gender processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1999;28:715–728. doi: 10.1023/a:1023277213129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Brown C, Groothusen J. The syntactic positive shift (SPS) as an ERP measure of syntactic processing. Language and Cognitive Processes. 1993;8:439–483. [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Federmeier KD, Coulson S, King JW, Muente TF. Language. In: Cacioppo JT, Tassinary GL, Berntson GG, editors. Handbook of Psychophysiology. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 576–601. [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Hillyard SA. Event-related brain potentials to grammatical errors and semantic anomalies. Memory and Cognition. 1983;11:539–550. doi: 10.3758/bf03196991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutas M, Neville HJ, Holcomb PJ. A preliminary comparison of the N400 response to semantic anomalies during reading, listening and signing. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology Supplement. 1987;39:325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville HJ, Nicol JL, Barss A, Forster KI, Garrett MF. Syntactically based sentence processing classes: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1991;3:151–165. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1991.3.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout L, Mobley LA. Event-related brain potentials elicited by failure to agree. Journal of Memory & Language. 1995;34:739–773. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio A. Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1991;45:255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Patel AD, Gibson E, Ratner J, Besson M, Holcomb PJ. Processing syntactic relations in language and music: An event-related potential study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:717–733. doi: 10.1162/089892998563121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter MC. Pictures in sentences: Understanding without words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1986;115:281–294. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.115.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallice T. Specialisation within the semantic system. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1988;5:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Teschner RV, Russell WM. The gender patterns of Spanish nouns: An inverse dictionary-based analysis. Hispanic Linguistics. 1984;1:115–132. [Google Scholar]

- van Berkum JJA, Brown CM, Hagoort P. Early referential context effects in sentence processing: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Memory and Language. 1999;41:147–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NY, Bates EA, Moreno EM, Kutas M. Potato not pope: Human brain potentials to gender expectation and agreement in Spanish spoken sentences. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;346:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NY, Moreno EM, Kutas M. Expecting gender: An event related brain potential study on the role of grammatical gender in comprehending a line drawing within a written sentence in Spanish. Cortex. 2003;39:483–508. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70260-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NYY. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of California-San Diego; La Jolla, CA: 2002. Grammatical gender in real-time language comprehension in Spanish: Behavioral and electrophysiological investigations. [Google Scholar]

- Wicha NYY, Bates EA, Orozco-Figueroa A, Reyes I, Hernandez A, Gavaldón de Barreto L. When zebras become painted donkeys: The interplay between gender and semantic priming in a Spanish sentence context. Language and Cognitive Processes. doi: 10.1080/01690960444000241. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]