Abstract

Background

The lifetime prevalence of self-reported asthma among Puerto Ricans is very high, with increased asthma hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and mortality rates. Differences in asthma severity between the mainland and island, however, remain largely unknown.

Objective

We sought to characterize differences in asthma severity and control among 4 groups: (1) Island Puerto Ricans, (2) Rhode Island (RI) Puerto Ricans, (3) RI Dominicans, and (4) RI whites.

Methods

Eight hundred five children aged 7 to 15 years completed a diagnostic clinic session, including a formal interview, physical examination, spirometry, and allergy testing. Using a visual grid adapted from the Global Initiative for Asthma, asthma specialists practicing in each site determined an asthma severity rating. A corresponding level of asthma control was determined by using a computer algorithm.

Results

Island Puerto Ricans had significantly milder asthma severity compared with RI Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and whites (P < .001). Island Puerto Ricans were not significantly different from RI whites in asthma control. RI Puerto Ricans showed a trend toward less control compared with island Puerto Ricans (P = .061). RI Dominicans had the lowest rate of controlled asthma. Paradoxically, island Puerto Ricans had more emergency department visits in the past 12 months (P < .001) compared with the 3 RI groups.

Conclusions

Potential explanations for the paradoxic finding of milder asthma in island Puerto Ricans in the face of high health care use are discussed. Difficulties in determining guideline-based composite ratings for severity versus control are explored in the context of disparate groups.

Keywords: Asthma, severity, control, clinical guidelines, Global Initiative for Asthma, Latino, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Rhode Island, health care use

Research on inequities in health care access, use, and quality between minorities and whites is a growing field in the United States. Puerto Rican children in the US mainland, for example, have a lifetime asthma prevalence rate ranging from 17.9% to 35%,1 which is higher than that of other racial/ethnic groups.2 The rate in Puerto Rico (PR) is even higher, ranging from 24% to 46%.1 Although differences in asthma severity between the mainland and the island remain largely unknown,3–5 Puerto Ricans on the mainland have higher hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and asthma mortality rates compared with other Latino groups.6 One drawback in this literature has been the limited input of direct clinical evaluation.

The majority of pediatric studies have used parental report of asthma diagnosis. The only direct comparison study involving a formal clinical evaluation at different sites was performed in the Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans (GALA) study, which analyzed Puerto Ricans and Mexicans in New York City, San Francisco, Mexico City, and San Juan.7 Although measures for studying asthma severity among Latinos have been applied,8 no studies to date have used national or international guidelines to characterize asthma severity between Puerto Ricans on the island versus those on the mainland. Less is known about differences in asthma severity between Puerto Ricans and other Caribbean groups who have migrated to the mainland, such as Dominicans.

The current study, part of the Rhode Island–Puerto Rico Asthma Center (RIPRAC) study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, examines disparities among (1) Puerto Ricans in PR, (2) Puerto Ricans in Rhode Island (RI), (3) Dominicans in RI, and (4) non-Latino whites in RI (herein referred to as whites). One of the study's main objectives was to characterize ethnic and site differences in asthma severity based on national and international guidelines in participants diagnosed with asthma ages 7 to 15 years, using a formal clinical evaluation by asthma specialists who practice in each locale. With the recent shift in asthma guidelines9 emphasizing asthma control instead of severity, analyses also characterized differences in asthma control among the study groups. Finally, ED and hospital use were examined, and corresponding interactions between study site and asthma severity or asthma control were explored with regard to use of asthma services.

METHODS

Participants

The sample was composed of 405 Puerto Ricans living in island PR and 112 Puerto Ricans, 137 Dominicans, and 151 whites living in RI. Subjects were recruited from convenience samples between 2003 and 2007. In PR 68.7% of the children were recruited from 4 independent provider organizations representative of the area and 2 hospital ambulatory pediatric clinics serving mostly medically indigent patients. To enroll more middle- to upper-income children with asthma, 29.4% of the sample was recruited from 26 private practice pediatric offices, and 2% was recruited from private referrals. Participants were primarily from the San Juan Metropolitan area, where 11% of the population resides.10 In RI 12% was recruited from hospital ambulatory clinics, 29% from community primary clinics, 20% from a hospital-based asthma educational program, 18% from health fairs and community events, 8% from schools, and 13% from grassroots sources. Ethnicity was determined based on self-report. To be classified as Puerto Rican or Dominican in RI, at least 1 of the child's parents had to self-identify as that ethnicity. Institutional review boards at Rhode Island Hospital and the University of Puerto Rico approved the study protocol (see additional Methods information in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Procedures

The study design was a cross-sectional, observational approach (4 sessions across a 4-month period). This report concentrates on the diagnostic clinic session, which included (1) asthma symptom history, both current and past; (2) description of medication regimen; (3) physical examination; (4) allergy testing; and (5) pulmonary function testing. Study questionnaires were administered by a trained research assistant, followed by an interview with the asthma specialist, who completed a physical examination and testing. Prebronchodilator FEV1 was measured by using a USB spirometer (Koko pneumotachometer; nSpire Health, Inc, Longmont, Colo), according to American Thoracic Society criteria.11

All instruments had equivalent forms in Spanish and English and were subjected to a stringent translation process (for methods, see Matías-Carrelo et al12). The entire research protocol was administered in English or Spanish by fluent interviewers, according to respondents' preferences.

Poverty threshold

An income/needs ratio was calculated for each family by dividing yearly household income by the poverty threshold for that family size.13,14 If the ratio was less than or equal to 1.0 during the year of participation, the family was considered at or below the poverty threshold.

Health services questionnaire

A health care services questionnaire was administered to parents to assess whether participants received regular asthma care (yes/no) and the place for the asthma care (private doctor's office, ED, urgent care center, and community health, hospital, or walk-in clinic).15

Asthma assessment

Rates of children's ED use and hospitalizations for asthma (in the previous 12 months) were determined based on parental report. Asthma symptoms were assessed by using a standardized questionnaire administered to parents.16 The original questionnaire assessed symptoms in the previous 12 months and was modified to include the past 4 weeks. Cronbach α values for English and Spanish versions and for 4-week and 12-month recall ranged from 0.72 to 0.83.

Asthma severity clinician rating

Study clinicians verified asthma diagnosis to determine eligibility for continued study participation by using a structured checklist. The clinician then determined an asthma severity rating by applying a visual grid, which used symptom frequency, prealbuterol FEV1, and current controller medication dose. The grid was adapted from the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA),17 which is based on National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel Report 2 (EPR-2) criteria18 with an added medication component if the subject was taking controller medication. The 4 levels of asthma severity were “mild intermittent,” “mild persistent,” “moderate persistent,” and “severe persistent” (see Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for a step-by-step method for determining severity). In addition to the severity rating, the clinician provided a confidence level of his or her rating.

TABLE E1.

Classification of asthma severity by daily medication regimen and response to treatment

| Current Treatment Step |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Symptoms and Lung Function on Current Therapy | Step 1: Intermittent | Step 2: Mild Persistent Level of Severity | Step 3: Moderate Persistent |

| Step 1: Intermittent | Intermittent | Mild Persistent | Moderate Persistent |

| Symptoms less than once a week | |||

| Brief exacerbations | |||

| Nocturnal symptoms not more than twice a month | |||

| Normal lung function between episodes | |||

| Step 2: Mild persistent | Mild Persistent | Moderate Persistent | Severe Persistent |

| Symptoms more than once a week but less than once a day | |||

| Nocturnal symptoms more than twice a month but less than once a week | |||

| Normal lung function between episodes | |||

| Step 3: Moderate persistent | Moderate Persistent | Severe Persistent | Severe Persistent |

| Symptoms daily | |||

| Exacerbations might affect activity and sleep | |||

| Nocturnal symptoms at least once a week | |||

| 60% < FEV1 < 80% predicted OR | |||

| 60% < PEF < 80% of personal best | |||

| Step 4: Severe persistent | Severe Persistent | Severe Persistent | Severe Persistent |

| Symptoms daily | |||

| Frequent exacerbations | |||

| Frequent nocturnal asthma symptoms | |||

| FEV1 ≤ 60% predicted OR | |||

| PEF ≤ 60% of personal best | |||

Reproduced with permission from www.ginasthma.org.

PEF, Peak expiratory flow.

Seven in-person meetings and 10 teleconferences involving all study clinicians at both sites were convened between 2002 and 2007 to ensure consistency across sites. In total, 60 cases were rated, exchanged, and discussed during these meetings. Cases deemed difficult to rate by 1 or more clinicians were discussed until consensus was reached.

Asthma control computer rating

After GINA released its updated guidelines in 2006 and the importance of the concept of asthma control was recognized, a computer algorithm was constructed for the study to determine asthma control levels for each subject19 based on symptoms and prealbuterol FEV1. Exacerbations were not included because hospitalizations and ED visits were a separate area of analysis in this study. The 3 resulting levels of asthma control were “controlled,” “partly controlled,” and “uncontrolled” (see Table E2 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for further detail).

TABLE E2.

Levels of Asthma Control

| Partly Controlled | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Controlled (All of the following) | (Any measure present in any week) | Uncontrolled |

| Daytime symptoms | None (Twice or less/week) | More than twice/week | Three or more features of partly controlled asthma present in any week |

| Limitations of activities | None | Any | |

| Nocturnal symptoms/awakening | None | Any | |

| Need for reliever/rescue treatment | None (Twice or less/week) | More than twice/week | |

| Lung function (PEF or FEV1)‡ | Normal | <80% predicted or personal best (if known) | |

| Exacerbations | None | One or more/year* | One in any week† |

Reproduced with permission from www.ginasthma.org.

PEF, Peak expiratory flow.

Any exacerbation should prompt review of maintenance treatment to ensure that it is adequate.

By definition, an exacerbation in any week makes that an uncontrolled asthma week.

Lung function is not a reliable test for children 5 years and younger.

Both severity and control were assessed once by using data from the clinic study visit. Some differences between the rating systems should be noted. The severity level was clinician determined, whereas the control level was computer determined. The severity level included symptoms over the previous 4 weeks and 12 months (to factor in seasonality and variable course), whereas the control level included symptoms over the previous 4 weeks to reflect current functioning. Only the severity assessment considered medication status.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses compared the asthma severity and control levels of the 4 study groups (island Puerto Ricans, RI Puerto Ricans, RI Dominicans, and RI whites) by using the χ2 test for associations among categorical measures. For differences in continuous variables among the 4 groups, a 1-way ANOVA was performed with the Student-Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. High outliers in ED/hospital use were trimmed to a value of 11 hospitalizations (n = 4) and 13 ED visits per year (n = 7). Secondary analyses for differences in reported medication use among the 4 groups were analyzed by using a 1-way ANOVA with Student-Neuman-Keuls post hoc tests. Univariate generalized linear models were used to test for site-by-severity and site-by-control interactions in tests assessing asthma outcomes. Each of the reported analyses was also conducted with age, sex, and poverty threshold as covariates. In every case, entering the covariates did not affect results. We report nonadjusted descriptive statistics.

The 4 study groups were compared for sociodemographics (poverty threshold) and health care opportunity (reported use of private doctor) by using univariate generalized linear model procedures to address site differences in recruitment sources. Group–by–poverty threshold and group–by–health care opportunity interactions were analyzed for both severity and control. Analyses were performed with SPSS version 12.0 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Ill). Statistical significance was set to .05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

One thousand nineteen participants enrolled in the study. One hundred sixty-three withdrew, were lost to follow-up, or were deemed ineligible to continue based on information gathered after enrollment, leaving a total of 856 participants who entered the clinical study session. After the clinical session, an additional 51 participants were excluded because they were determined not to have asthma or met exclusionary criteria (eg, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and vocal cord dys-function) that would interfere with the diagnosis of asthma or the ability to participate in the study. The final sample included 805 participants.

Table I lists subject characteristics. There were no differences in age or sex across the 4 study groups. There were fewer participants below the poverty threshold (F = 69.1, P < .001) among RI whites. More than half to nearly two thirds of the Latino groups were below the poverty threshold, with no differences among mainland and island Puerto Ricans and Dominicans.

TABLE I.

Subject characteristics (n = 805)

| PR (n = 405) | RI-PR (n = 112) | RI-DR (n = 137) | RI white (n = 151) | Post hoc comparisons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry (y), mean ± SD | 10.7 ± 2.5 | 10.6 ± 2.4 | 10.6 ± 2.5 | 10.5 ± 2.6 | NS |

| Female sex (%) | 44 | 48 | 47 | 35 | NS |

| Poverty threshold (%) | 65 | 61 | 58 | 15 | PR, RI-PR, RI_DR > RI white* |

| Private doctor for asthma (compared with ED/community clinic/hospital clinic/walk-in/urgent care center; %) | 44 | 44 | 63 | 76 | PR, RI-PR < RI-DR < RI white* |

PR, Puerto Rican; RI-PR, RI Puerto Rican; RI-DR, RI Dominican; NS, not significant.

P < .001.

More whites and Dominicans in RI reported seeing a private doctor for asthma compared with Puerto Ricans (χ2 = 54.6, P < .001, Table I). There were no differences in use of a designated doctor for asthma between island Puerto Ricans and RI Puerto Ricans, who reported using either an ED, community health clinic, hospital clinic, walk-in clinic, or urgent care center for their asthma more than half the time.

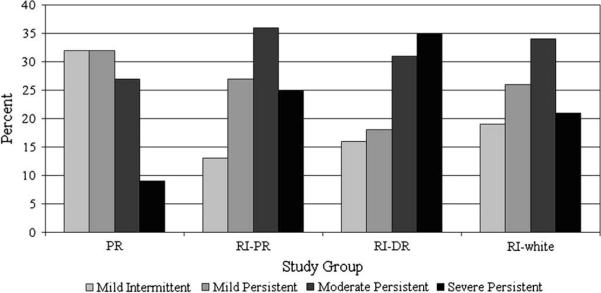

Asthma severity

Asthma severity differed between sites, with island Puerto Rico skewed toward mild intermittent/mild persistent asthma, and RI skewed toward moderate/severe persistent asthma (Fig 1). Island Puerto Ricans had significantly milder asthma compared with RI Puerto Ricans (χ2 = 32.9, P < .001), RI Dominicans (χ2 = 60.4, P < .001), and RI whites (χ2 = 22.5, P < .001). There was no significant difference in severity among the 3 groups in RI.

FIG 1.

Asthma severity distribution by study group. Puerto Ricans (PR) had significantly milder asthma compared with RI Puerto Ricans (RI-PR; P < .001), RI Dominicans (RI-DR; P < .001), and RI whites (P < .001). There were no significant differences among the 3 groups in RI.

Asthma control

Control categories were collapsed into controlled versus partially controlled/uncontrolled asthma for ease of presentation. RI Dominicans (11%) had significantly lower rates of controlled asthma than RI whites (23%, χ2 = 7.2, P < .01) and island Puerto Ricans (24%, χ2 = 10.5, P < .01). Island Puerto Ricans were not significantly different from RI whites in their proportion of controlled asthma and showed a trend toward more control than RI Puerto Ricans (15% controlled, χ2 = 3.5, P = .061).

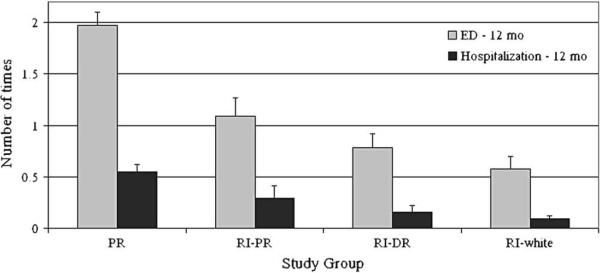

ED visits and hospitalizations

Island Puerto Ricans had more ED visits in the previous 12 months (F = 21.5, P < .001) compared with the 3 RI groups (Fig 2). Island Puerto Ricans had more hospitalizations compared with RI whites and RI Dominicans (F = 7.7, P < .001). RI Puerto Ricans did not differ significantly from island Puerto Ricans in hospitalizations. There were no site-by-severity or site-by-control interactions for ED visits or hospitalizations in the past 12 months.

FIG 2.

ED visits and hospitalizations in the past 12 months by study group. Puerto Ricans (PR) had significantly more ED visits (P < .001) compared with the 3 groups in RI. Island Puerto Ricans had more hospitalizations compared with RI whites and RI Dominicans (RI-DR; P < .001). RI Puerto Ricans (RI-PR) were not significantly different from island Puerto Ricans in hospitalizations.

Secondary analyses

Role of medication

The 4 study groups differed in their reported use of controller medications (Table II). Island Puerto Ricans reported the least amount of inhaled steroids, followed by RI Dominicans and then both RI whites and RI Puerto Ricans (F = 34.5, P < .001). There was no difference in report of inhaled steroid use between RI whites and RI Puerto Ricans. Of the 4 groups, island Puerto Ricans also reported the least amount of any controller medication (F = 33.8, P < .001). There was no difference among the 3 groups in RI in any controller medication. An interaction emerged between site and severity when examining reported medication use. More inhaled steroids were reported at a lower severity level in RI subjects. In contrast, there were no site-by-control interactions for reported medication use. Those with more controlled asthma did not report more inhaled steroids than those with uncontrolled asthma, regardless of site. A similar pattern was found for any controller medication.

TABLE II.

Medication status (n = 805)

| PR (n = 405) | RI-PR (n = 112) | RI-DR (n = 137) | RI white (n = 151) | Post hoc comparisons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhaled steroid use (%) | 15 | 48 | 34 | 50 | PR < RI-DR < RI-PR, RI white* |

| Any controller medication (%) | 32 | 65 | 63 | 68 | PR < RI-PR RI-DR, RI white* |

PR, Puerto Rican; RI-PR, RI Puerto Rican; RI-DR, RI Dominican; NS, not significant.

P < .001.

Pulmonary function

RI whites had the highest mean prebronchodilator FEV1 percent predicted (Mean, 92%; SD, 14%), followed by both RI Puerto Ricans (Mean, 88%; SD, 12.2) and island Puerto Ricans (Mean, 87%; SD, 13%) and then by RI Dominicans (Mean, 82%; SD, 12.4%; F = 14.4, P < .001). There was no difference in FEV1 percent predicted between island and mainland Puerto Ricans. There was no difference in FEV1 reversibility among the 4 groups.

Poverty threshold and health care opportunity

We examined sociodemographic factors that might have been related to differences in severity and found a significant poverty (above/below threshold)–by–group (island Puerto Rican, RI Puerto Rican, RI Dominican, and RI white) interaction (F = 3.7, P < .05). Similarly, there was a health care opportunity (private vs nonprivate doctor)–by–group interaction for severity (F = 5.2, P < .01). When examining means across the groups, however, the interaction effects appeared to be driven mainly by the RI whites. More RI whites had a higher severity level if they were below the poverty threshold or if they did not see a private doctor for their asthma. When RI whites were removed from the analysis, there were no significant interactions among the 3 Latino groups (island Puerto Rican, RI Puerto Rican, and RI Dominican) and poverty threshold or health care opportunity. Further analyses were not conducted, given that Latino groups were the main focus of interest and interactions at the Latino group level were not significant.

DISCUSSION

We found a difference in the asthma severity distribution between study participants living in PR and RI using guideline-based composite ratings for severity. Furthermore, ED visits for asthma were higher in PR, even though the asthma severity of island Puerto Ricans was milder compared with that of Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and whites living in RI. In addition, we found better asthma control among island Puerto Ricans at a level comparable with that seen among RI whites. Although prior studies have documented that asthma is more prevalent in Puerto Ricans in both PR and the mainland United States, our findings add information about asthma severity, which has been largely understudied in reference to this ethnicity effect.

Several studies have promoted the notion that island and mainland Puerto Ricans have more severe asthma than other groups based on self-reported asthma attack rates2 or lifetime hospitalizations.3 The first study (GALA) to examine pulmonary function between Latino ethnic subgroups found lower bronchodilator responsiveness among Puerto Ricans compared with Mexicans, a group that had the lowest lifetime asthma diagnosis rate and attack prevalence in the US mainland, even lower than whites.2 GALA therefore compared 2 extremes of the prevalence spectrum without reference to groups in between, such as whites, blacks, Dominicans, or Cubans. Furthermore, it did not adjust for different controller medication types or doses, and participants had to be uncontrolled a certain portion of the year at study entry, which might explain the lower lung function found among Puerto Ricans in their study.7 Moreover, the study population had a high rate of inhaled corticosteroid use (56.5%) on the island20 compared with medication rates of Medicaid patients (17.5%) for the same health region and year. This suggests the group in PR might have been a specialty group with more access to medication relative to the general population, although no data regarding the socioeconomic status of GALA participants were provided.

Therefore our results are valuable and merit further study because they are the second published study using a direct clinical observation of Puerto Ricans on the island, including patients below the poverty threshold. Our convenience sample is a limitation, however, and results need to be replicated with a randomly selected or probability community sample.

Health care access issues

Consistent with previous studies is the high health care use (both hospital and ED use) found among Puerto Ricans. GALA also demonstrated high ED rates for Puerto Ricans with mild asthma. Potential reasons for this paradox (high use despite low severity) include different norms that might lead island Puerto Ricans to visit the ED, even for milder symptoms. In PR the Health Department installed a new health policy in 1995 to transform the delivery of health care into a managed care system. This model has increased access to care by providing a wider net of providers to the medically indigent. Because medication and specialist costs come out of primary care providers' capitation, the system discourages referral to specialists and prescription of costly medications.21 Medications, particularly anti-inflammatory asthma controllers, are restricted under PR's capitation health policy, and families can obtain free medications from EDs. Primary care clinicians therefore have incentive to refer families to EDs, which might explain some of our findings.

In addition, the threshold for seeking emergency care might be lower among island Puerto Ricans. Puerto Rican adults have been shown to endorse higher levels of symptom-related emotional distress than whites,22 which might lead them to access emergency services more often. Our findings suggest a similar phenomenon might be occurring within the family context. We will address this issue in future reports from this study.

Severity rating conundrum

A limitation of this study (and other studies of children's asthma) is reliance on imperfect measures. Our comprehensive severity assessment relied on self-report of medication, which presumes adequate health care access. This has not changed in the Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3), which recommends that asthma severity be inferred after optimal therapy is established by correlating levels of severity with the lowest level of treatment required to maintain control.9 We have demonstrated, however, that dependence on medication level for severity ratings can be biased by different health care systems.

Ongoing limitations of severity ratings are evident in the literature.19,23–26 We attempted to provide validity to our subjective clinician rating with a computer severity rating (not to be confused with the computer control rating) derived from an algorithm developed at National Jewish Hospital.27 The κ coefficient between clinician severity rating and computer severity rating was low at 0.26 (P < .01). This level of concordance is consistent with other studies, which show severity ratings differ substantially by method (κ coefficients in the 0.1–0.3 range).28 For example, agreement between clinician raters compared with EPR-2 (weighted κ = 0.2) and GINA (weighted κ = 0.25) in a multicenter trial was of similar magnitude.29 Among 14 pediatric allergists and pulmonologists using EPR-2 to rate severity, agreement was also poor (κ = 0.29) and even lower when they were asked the main factors used in their assessment (κ = 0.19).30 Therefore our methods, although less than ideal, are similar to other findings in the literature.

With these limitations, why not examine spirometry alone (eg, Burchard et al7), albuterol use, or nocturnal symptoms? Pulmonary function often does not correlate directly with symptoms,31,32 and both are thought to measure different aspects of asthma.33 This is particularly true when these measures are taken after the onset of treatment, as was the case in our study. For this reason, EPR-39 continues to emphasize the importance of using multiple measures in a comprehensive assessment of asthma. Until adequate biomarkers of severity are discovered (that are not confounded by treatment), we are limited by multiple subjective and objective clinical indicators, with various combinations that present both clinicians and researchers with a “severity conundrum.”

Control

We speculate that island Puerto Ricans were the most different with respect to severity in part because of health care access issues (they were not using asthma controller therapy as often and therefore were not ranked as severe as RI participants). When we examined asthma control (which does not include medication), however, island Puerto Ricans had good control and were similar to RI whites. In comparison, RI Puerto Ricans had marginally worse control, and RI Dominicans fared the worst.

If asthma is poorly controlled among Dominicans, why is their health care use not higher? The data suggest something protective about being Dominican that might mediate risk for using the ED or hospital, which is in contrast to RI Puerto Ricans, who were similar to island Puerto Ricans in hospitalization rate. Other studies have found lower self-reported asthma prevalence and attack rates among Dominicans compared with mainland Puerto Ricans,2 even for Dominicans who live in the same buildings and neighborhoods as Puerto Ricans.34 Differences in acculturative stress and social networks between RI Latino subgroups are potential explanations for our findings35 and will be discussed in future reports. We note that inhaled steroid rates were lower for the Dominicans in our study, although they more often reported going to a designated doctor for their asthma compared with Puerto Ricans (see the Discussion section of this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org for discussion of RI Latinos).

Several study limitations bear mention. Ethnicity was based on self-report. We did not assess genetics in this study because the best approaches for studying admixed populations are still being developed.36

The wide age range sampled could potentially bias symptom report for adolescent participants, spirometry technique in the younger children, or the natural course of asthma itself; however, study groups did not differ significantly by age. Moreover, when we controlled for age as a covariate, there was no difference in study conclusions.

Asthma control and severity were not measured over several time points but only at the clinic visit. EPR-3 now recommends severity to be assessed at baseline and then asthma control at subsequent visits. That is easily done in a clinic setting during follow-up visits, but multiple clinician visits were not part of this study design. In addition, health care use was removed from the analysis of control because of interest in the association of severity and morbidity. Clinicians were not blinded to health care use in their severity ratings but were aware of health care access issues on the island.

There are no published pulmonary function reference values for Puerto Ricans. Because one of our groups was white and not Mexican, we used Polgar reference values37 to determine FEV1 percent predicted values as opposed to Hankinson et al's methods,38 which were used by the GALA study group. We did not include an island Dominican group in the study design, a potential future direction. Finally, parent-reported medical history and frequency of symptoms are subject to recall bias and were not verified.

Conclusion

This report opens new areas for discussion in examining known disparities in asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality that Puerto Ricans face both in island PR and the mainland United States. Although asthma prevalence and emergency health care use are greater in island PR, we found asthma severity to be milder among our island Puerto Rican sample compared with Puerto Rican, Dominican, and white samples living in RI. Several explanations for this paradox have been presented and will be explored further in future reports. This is the first study that has used published guidelines for asthma severity classification comparing Puerto Ricans on the island and the mainland.

METHODS

Asthma severity clinician rating

Study clinicians verified asthma diagnosis to determine eligibility for the subject's continued participation in the study using a structured checklist and clinical judgment. The study clinician then determined an asthma severity rating using a visual grid, which classified severity by using symptom frequency, prealbuterol FEV1, and current controller medication dose. The grid was adapted from the GINA,E1 which is based on National Asthma Education and Prevention ProgramE2 criteria with an added medication component if the subject was taking controller medication. The 4 levels of asthma severity were “mild intermittent,” “mild persistent,” “moderate persistent,” and “severe persistent” (see Table E1 for the original GINA table).

For easier use, we modified the original Table E1 to include a listing of all the medications under each step. For example, step 2 had a listing of the dose ranges for low-dose inhaled steroids, leukotriene modifier, cromolyn, nedocromil, and so on. Step 3 had a list of medium-dose inhaled steroids and combination inhaled steroids and long-acting β2-agonists, for example. We added a step 4 column to the right for severe persistent asthma. By default, all cells of that column were populated as “severe persistent.”

The table column on the left indicates the different levels for symptoms and FEV1 based on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute EPR-2, assuming no controller medication. Given that many patients are already taking medications at a visit, GINA 2002 incorporated a medication piece that would increase the severity rating according to dose and class. These are all the columns to the right. During a study clinic visit, after seeing a participant, the study clinician would mark the appropriate medication column (eg, step 1, 2, 3, or 4) that matched the patient, as well as the appropriate symptom/FEV1 row, and see where they intersected. If symptom level did not match FEV1, then the worse of the 2 was considered.

For example, if a patient taking Flovent 44, 2 puffs twice daily (mild persistent level), was having nocturnal symptoms more than twice a month but less than once a week and FEV1 was normal, the person was rated as having moderate persistent asthma. If FEV1, however, was not normal (eg, 65% of predicted value) with the same symptoms, the same participant would be rated as having severe persistent asthma. An adherence component was also added, such that if subjects reported missing their medication more than half the time, they were considered nonadherent and in column 1 (step 1, no controller medication).

Asthma control computer rating

After GINA released its updated guidelines in 2006E3 toward the end of the RIPRAC study and the concept of asthma control gained popularity, a computer algorithm was constructed to determine the asthma control level for each RIPRAC subject based on symptoms and prebronchodilator FEV1 (see Table E2 for the original GINA table).

The first column denotes the characteristic measured (ie, daytime symptoms, limitations of activities, nocturnal symptoms/awakenings, need for reliever/rescue treatment, and lung function [peak expiratory flow or FEV1]). We used a time-frame of the past 4 weeks at the participants' baseline interview. The first column denotes that if all of the areas are met, the computer classifies the participant's symptoms as “controlled.” The second column denotes that if any 1 measure present in any week is not met, the computer classifies the participant's symptoms as “partly controlled.” The third column indicates that if 3 or more features are not met in any week, the computer classifies the patient's symptoms as “uncontrolled.” Syntax was written to reflect this.

Some modifications were included. The table does not indicate where 2 unmet features in any week fall, and therefore we classified those patients' symptoms as “partly controlled” by default. Also, we did not include exacerbations for the following reasons. First, we did not gather data for frequency of oral steroid use over the past 4 weeks at baseline. Second, the asthma control measure was an add-on as the concept gained favor in national guidelines only towards the end of study. Asthma severity (before EPR-3 was published) was the primary measure of the study, and oral steroids were not systematically included as part of a risk domain yet. Third, we could not use ED/hospitalizations as a proxy for exacerbations when we found such high rates of ED/hospitalizations in island Puerto Ricans that suggested health care access differences and a potential confounder in the final rating.

Asthma control and severity used for this article were not measured over several time points but only at the clinic visit at baseline.

DISCUSSION

RI Puerto Rican and Dominican sample

Given that this was a convenience sample, a description of how representative the Latino sample of the US mainland is warranted. Latinos comprise 15.5% of the population in the Northeastern United States. Most Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in the US mainland live in the Northeast (63.8% of Puerto Ricans and 83.3% of Dominicans).E4 In RI 8.7% of the population is composed of Latinos (of whom 28% are Puerto Rican and 19.7% are Dominican).E5 The Latinos in RI come primarily from other northeastern cities, such as New York and Hartford, Connecticut, and therefore reflect similar experiences. Many of the Latinos in RI are urban (57% live in Providence and 79% live in one of the 3 main cities).

In RI 11% of children from birth to 17 years old reported having asthma from 2001 to 2005. Only 4 states report higher asthma prevalence rates.E6

The educational attainment of Latinos is low in both RI and the United States in general. In RI 47.9% of Latinos finished 12 grades or less.E5 In the US mainland, 36.2% of Latinos have no high school diploma.E4 Similarly, in our study 37.5% of RI Puerto Rican mothers and 29.9% of RI Dominican mothers had no high school diploma.

There is a high rate of poverty among both RI and mainland Latinos. Latinos below the poverty rate for a child younger than 18 years are 49.8% in RI, 35.8% in the Northeast, and 30.3% in the mainland United States.E5 In our study sample 61% of RI Puerto Ricans were below the poverty threshold, and 58% of RI Dominicans were below the poverty threshold. Therefore our study sample was poorer than average (but very similar to island Puerto Ricans, as noted in the text).

Latinos in RI are newcomers, with 30% coming to the United States since 1990. Forty-eight percent of all Puerto Ricans (children and adults) in RI are born on the mainland,E5 with comparable numbers on a national level.E4 In contrast, 4.3% of Dominican parents and children from a national dataset were born in the United States (parent and child data were not provided separately).E4 In our study sample 8% of RI Dominican parents and 75% of RI Dominican children were born on the mainland. Similar to national data, therefore, Dominicans in our study sample appear to be more recent immigrants compared with Puerto Ricans.

RI ranks 11th in the nation for insurance coverage. The rate of uninsured children younger than 18 years is 6.9%, which is lower than the national average of 11.2%.E6

In summary, the RI Latino sample appears to be comparable to the US Latino population in multiple areas, although it appears that our sample was poorer than average but live in a state where they are more likely to receive health care coverage (see Table E3 for summary).

TABLE E3.

RI Puerto Ricans and Dominicans

| Variable | RI Puerto Ricans | RI Dominicans | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry (y), mean ± SD | 10.6 ± 2.4 | 10.6 ± 2.5 | NS |

| Female sex (%) | 48 | 47 | NS |

| Maternal education (y completed) | 11.6 | 12.1 | NS |

| Poverty threshold (%) | 61 | 58 | NS |

| Parent nativity, born in US mainland (%) | 32 | 8 | <.001 |

| Language of interview (% English) | 46 | 15 | <.001 |

| Use of private doctor for asthma (compared with ED/community health center/walk-in clinic, etc; %) | 44.1 | 63.2 | <.01 |

For the purposes of this article, we measured acculturation by birthplace of parent informant and language of interview. As noted in Table E3, there were differences between RI Puerto Ricans and RI Dominicans on these measures, but the differences were not relevant to our main substantive conclusions when we analyzed group (RI Puerto Rican and Dominican) by acculturation (language of interview, parent informant nativity) for severity or control. Level of acculturation and the nuances of its various measures in this study are being examined in more detail in another report.E7

Island Puerto Rican sample

The population of Island PR is 3,808,610, and 11% (434,374) live in San Juan Municipio,E8 where we recruited most of our participants.

At present, and since 1994, the government in PR purchases health care for all medically indigent patients from managed care companies through independent provider associations. Children's gatekeepers are pediatricians. In the San Juan Metropolitan Area there are 17 independent provider associations that provide outpatient care for children and are subcontracted by one insurance company, MCS Health Management Options. This company in turn is contracted by a government Agency called ASES, for its Spanish acronym. We chose the clinics based on what is considered by both the MCS administrator and the director of ASES as representative of all other independent provider association clinics in the San Juan metropolitan area. In addition, the investigators in PR sampled from 26 private offices of pediatricians in the San Juan area to include middle and upper middle class children in our sample. Initially, we thought that we could obtain all the high-income patients from these clinics but realized later that poor people also attended the clinics. We then decided to screen for income level by asking patients what kind of insurance they had. Medicaid recipients in PR have to be 200% below the poverty level. As noted in the text, 65% of the island Puerto Rican sample was below the poverty threshold compared with 48% of the island Puerto Rican population at large.E8

Clinical implications: Asthma severity/control among Latinos presents a complex picture. Understanding group differences will facilitate patient management. Given that severity determination remains subjective, a biomarker might be needed when studying different health care systems.

Acknowledgments

Supported by U01-H1072438 (G. C. and G. F, P.I.s) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. G. C.'s time is also supported by 5P60 MD002261-02 from the National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities.

E. L. McQuaid has received research support from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute of Children's Health and Development, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. G. K. Fritz has received research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Institute of Mental Health, and is an editor at Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. R. Seifer has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Administration for Children and Families, the National Science Foundation, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. D. Koinis-Mitchell has received research support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. A. N. Ortega has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

We thank the participants and their families for their participation and acknowledge the dedicated work of research assistants, clinic recruiters, and clinic staff at both sites. We thank Hector Cordero, MD; Ali Yalcindag, MD; Beata Nelken, MD; Lilia Romero-Bosch, MD; and Diane Andrade, RNC, for their clinical expertise in RI. We also thank Vivian Febo, PhD; Moraima Rivera; Jaime Colon; and Vilmary Cruz for coordinating protocol specifics among the different clinics in PR.

Abbreviations used

- ED

Emergency department

- EPR-2

Expert Panel Report 2

- EPR-3

Expert Panel Report 3

- GALA

Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans

- GINA

Global Initiative for Asthma

- PR

Puerto Rico

- RI

Rhode Island

- RIPRAC

Rhode Island–Puerto Rico Asthma Center

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The rest of the authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loyo-Berrios N, Orengo J, Serrano-Rodriguez R. Childhood asthma prevalence in northern Puerto Rico, the Rio Grande, and Loíza experience. J Asthma. 2006;43:619–24. doi: 10.1080/02770900600878693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117:43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shen S, Rosner BA, Celedon JC. Area of residence, birthplace, and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Chest. 2007;131:1331–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen RT. Celedón JC. Asthma in Hispanics in the United States. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canino G, Koinis Mitchell D, Ortega A, McQuaid E, Fritz G, Alegria M. Asthma disparities in the prevalence, morbidity and treatment of Latino children. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2926–37. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunninghake GM, Weiss ST, Celedón JC. State of the art: asthma in Hispanics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:143–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1232SO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burchard EG, Avila PC, Nazario S, Casal J, Torres A, Rodriguez-Santana JR, et al. Lower bronchodilator responsiveness in Puerto Rican than in Mexican subjects with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:386–92. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1293OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega AN, Belanger KD, Bracken MB, Leaderer BP. A childhood asthma severity scale: symptoms, medications, and health care visits. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:405–13. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program . Expert Panel Report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Census Bureau [Accessed November 2008];Census 2000 demographic profile highlights. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov.

- 11.American Thoracic Society Standardization of spirometry: 1994. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matías-Carrelo L, Chavez LM, Negrón G, Canino G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Hoppe S. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of five outcome measures. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:291–313. doi: 10.1023/a:1025399115023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of growing up poor. Russel Sage Publications; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services . The 2005 HHS poverty guidelines. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortega A, Gergen P, Paltiel A, Bauchner H, Belanger K, Leaderer B. Impact of site care, race, and Hispanic ethnicity on medication use for childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e1. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosier MJ, Bishop J, Nolan T, Robertson CF, Carlin JB, Phelan PD. Measurement of functional severity of asthma in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1434–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global Initiative for Asthma [Accessed November 2008];Original: workshop report, global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2002 http://www.ginasthma.org/GuidelineItem. asp?intId=82.

- 18.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program . Expert Panel Report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Initiative forAsthma Revision:GINA report, global strategyforasthma management and prevention. [Accessed November 2008];Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2006. http://www.ginasthma.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=1388.

- 20.Burchard EG, Avila PC, Nazario S, Casal J, Torres A, Rodriguez-Santana JR, et al. [Accessed April 2009];Lower bronchodilator responsiveness in Puerto Rican than in Mexican subjects with asthma (on-line supplement) doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1293OC. Available at: http://171.66.122.149/cgi/data/169/3/386/DC1/1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Alegría M, McGuire T, Vera M, Canino G, Matías L, Calderón J. Changes in access to mental health care among the poor and nonpoor: results from the health care reform in Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1431–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coelho V, Strauss M, Jenkins J. Expression of symptomatic distress by Puerto Rican and Euro-American patients with depression and schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:477–83. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199808000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calhoun WJ, Sutton LB, Emmett A, Dorinsky PM. Asthma variability in patients previously treated with beta2-agonists alone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1088–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chipps B, Spahn J, Sorkness C, Baitinger L, Sutton L, Emmett A, et al. Variability in asthma severity in pediatric subjects with asthma previously receiving short-acting β2-agonists. J Pediatr. 2006;148:517–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwok M, Walsh-Kelly C, Gorelick M, Grabowski L, Kelly K. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program severity classification as a measure of disease burden in children with acute asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;117(suppl):S71–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2000D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuhlbrigge A. Asthma severity and asthma control: symptoms, pulmonary function, and inflammatory markers. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:1–6. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federico M, Wamboldt F, Carter R, Mansell A, Wamboldt M. History of serious asthma exacerbations should be included in guidelines of asthma severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Kirking DE, SR Methods of measuring asthma severity and influence on patient assignment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:449–54. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller M, Johnson C, Miller D, Deniz Y, Bleecker E, Wenzel S. Severity assessment in asthma: an evolving concept. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:990–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker K, Brand D, Hen J., Jr Classifying asthma: disagreement among specialists. Chest. 2003;124:2156–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stout JW, Visness CM, Enright P, Lamm C, Shapiro GG, Vanthaya NG, et al. Classification of asthma severity in children: the contribution of pulmonary function testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:884–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bacharier LB, Strunk RC, Mauger D, White D, Lemanske RF, Jr, Sorkness CA. Classifying asthma severity in children: mismatch between symptoms, medication use, and lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:426–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shingo S, Zhang J, Reiss T. Correlation of airway obstruction and patient-reported endpoints in clinical studies. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:220–4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ledogar RJ, Penchaszadeh A, Garden CC, Iglesias G. Asthma and Latino cultures: Different prevalence reported among groups sharing the same environment. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:929–35. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koinis Mitchell D, McQuaid E, Kopel S, Klein R, Seifer R, Esteban C, et al. Migration and asthma morbidity in Latino children. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Thoracic Society; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. May 16-18, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choudhry S, Seibold M, Borell L, Tang H, Serebrisky D, Chapela R, et al. Dissecting complex diseases in complex populations: asthma in Latino Americans. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:226–33. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-029AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polgar G, Promadhat V. Pulmonary function testing in children: techniques and standards. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hankinson JL, Odencratz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Global Initiative for Asthma [Accessed November 2008];Original: workshop report, global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2002 http://www.ginasthma.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=82.

- E2.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program . Expert Panel Report 2: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Bethesda: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Global Initiative for Asthma [Accessed November 2008];Revision: GINA report, global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2006 http://www.ginasthma.org/GuidelineItem.asp?intId=1388.

- E4.Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117:43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Rhode Island Foundation [Accessed November 2008];RI Latinos. Available at: http://www.rifoundation.org/matriarch/OnePiecePage.asp_Q_PageID_E_221_A_PageName_E_AboutPubsSpecialTopicsLatino.

- E6.Rhode Island Kids Count [Accessed November 2008];2008 Rhode Island Kids Count factbook. Available at: www.kidscount.org.

- E7.Koinis Mitchell D, McQuaid E, Kopel S, Klein R, Seifer R, Esteban C, et al. Migration and asthma morbidity in Latino children. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Thoracic Society; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. May 16–21, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- E8.US Census Bureau [Accessed November 2008];Census 2000 demographic profile highlights. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov.