Abstract

Despite widespread belief that moods are affected by the menstrual cycle, researchers on emotion and reward have not paid much attention to the menstrual cycle until recently. However, recent research has revealed different reactions to emotional stimuli and to rewarding stimuli across the different phases of the menstrual cycle. The current paper reviews the emerging literature on how ovarian hormone fluctuation during the menstrual cycle modulates reactions to emotional stimuli and to reward. Behavioral and neuroimaging studies in humans suggest that estrogen and progesterone have opposing influences. That is, it appears that estrogen enhances reactions to reward, but progesterone counters the facilitative effects of estrogen and decreases reactions to rewards. In contrast, reactions to emotionally arousing stimuli (particularly negative stimuli) appear to be decreased by estrogen but enhanced by progesterone. Potential factors that can modulate the effects of the ovarian hormones (e.g., an inverse quadratic function of hormones’ effects; the structural changes of the hippocampus across the menstrual cycle) are also discussed.

Keywords: emotion, reward, menstrual cycle, estrogen, progesterone

In life, we often encounter hedonic stimuli, such as happy faces, appealing animals, money, car accidents, and stressful events. These hedonic stimuli sometimes induce strong physiological arousal (i.e., emotional arousal) that modulates subsequent cognitive processing (for a review see Mather & Sutherland, 2011). Some hedonic stimuli (e.g., money; high-calorie foods) can also serve as reinforcers (i.e., reward), increasing the frequency of behaviors that lead to their acquisition (e.g., Berridge, 2003; Kringelbach, 2005). Given the importance of these stimuli in our life, reward and emotion have been intensively examined in many fields, such as social neuroscience, cognitive science, affective neuroscience, behavioral economics, and neuroeconomics.

While traditional studies in these areas examined common patterns across different people regardless of their sex, a growing body of research demonstrates sex differences in how people react to and process rewards and emotional stimuli (see Andreano & Cahill, 2009; Cahill, 2006; Caldú & Dreher, 2007; Hamann & Canli, 2004; Kajantie & Phillips, 2006; Kudielka & Kirschbaum, 2005 for reviews). One possible reason for these sex differences is that ovarian hormones alter reactions to emotional stimuli and to rewards. For example, the same emotional stimuli may induce different arousal reactions and neural responses in brain regions modulating arousal depending on ovarian hormone levels. Brain regions involved in reward processing might also respond differently depending on ovarian hormone levels. To address these possibilities, in the current paper, we review behavioral and neuroimaging findings on the effects of the menstrual cycle on reactions to emotional stimuli and to rewards.

Before further discussing the effects of ovarian hormones, we first describe our definitions of emotional stimuli and reward. Emotional stimuli are often characterized based on two orthogonal dimensions (Russell & Carroll, 1999): valence (positive or negative) and physiological arousal. Previous studies revealed that the amygdala, which is a key region for emotion (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005), responds to the intensity of physiological arousal induced by positive or negative stimuli (Anderson et al., 2003; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004; Shabel & Janak, 2009). However, the amygdala does not respond to the intensity of neutral stimuli (Winston, Gottfried, Kilner, & Dolan, 2005). This valence by intensity interaction is consistent with the notion that both arousal and valence are important aspects of emotional stimuli.

In contrast, reward has been defined as an instrumental reinforcer which triggers 'wanting' or craving (i.e., incentive salience) and increases the frequency of behaviors contingent with it (e.g., Berridge & Robinson, 2003; Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2009). Reward has been associated with brain regions involved in dopaminergic processing, such as the striatum (including nucleus accumbens), globus pallidus, and ventral tegmental area (Berridge, 2003; Berridge et al., 2009). Rewards overlap with emotional stimuli (particularly emotionally positive stimuli), as they can produce emotional consequences (e.g., earning money could be a reinforcer but might also evoke emotional arousal). In fact, rewards sometimes activate the amygdala (Camara, Rodriguez-Fornells, & Munte, 2009). Likewise, emotionally positive stimuli sometimes activate the reward-related regions in the brain (Phan, Wager, Taylor, & Liberzon, 2002).

However, emotional stimuli do not always serve as reinforcers and do not necessarily have strong incentive salience. For example, seeing people cerebrating their victory at the Olympics can induce emotional arousal, but does not necessarily alter one's behavior or induce craving for victory. Similarly, rewards can serve as reinforcers even when they do not have positively valenced meanings (Berridge, 2003; Berridge et al., 2009). In the current paper, therefore, "reward" is defined as an instrumental reinforcer which increases the frequency of contingent behaviors while evoking feelings of ‘wanting’ or craving. In contrast, we use the term "emotional stimuli" to refer to valenced stimuli that induce physiological arousal (regardless of positive or negative valence), affecting cardiovascular activity, heart rate, skin response, and pupil dilation. Emotional stimuli induce multiple reactions, including physiological arousal, stress hormones, amygdala activity, and subjective feelings. Similarly, rewards can alter physiological states (e.g., heart rate), activity in reward-related regions in the brain, and subjective experiences. In the current paper, we review the effects of ovarian hormones without discriminating these different aspects of reactions.

Ovarian Hormone Changes across Menstrual Cycle

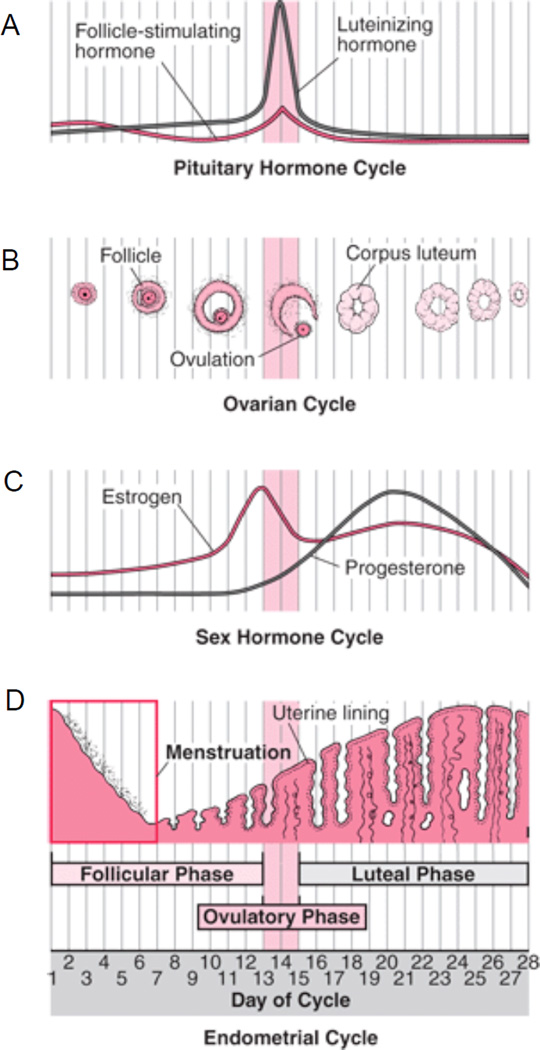

The human menstrual cycle lasts 28 days on average and is divided into follicular and luteal phases. The follicular phase begins with the onset of menstruation on day 1 and continues until ovulation (typically on day 14), and the luteal phase begins at ovulation and continues until the onset of menstruation (typically days 15–28; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The human menstrual cycle. Day 1 of the cycle is defined as the first day of menstruation, with ovulation occurring on day 14 in a typical 28-day cycle. The follicular phase starts on day 1 and continues until ovulation, which is followed by the luteal phase. The menstrual cycle in healthy women is associated with A) pituitary hormone changes, B) development of ovarian follicles, C) changes in estrogen and progestrone level, and D) changes in the thickness of the uterine lining (From The Merck Manual Home Health Handbook, edited by Robert S. Porter. Copyright © 2004–2011 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ., U.S.A. Available at http://www.MerckManuals.com/home. Accessed 10/5/2011).

The early follicular phase begins with release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH: Barr, 1999; Raven, Johnson, Singer, & Losos, 2005; Rimsza, 2002). FSH stimulates the growth of a number of ovarian follicles that secrete estrogen as they mature. When one of the developing follicles becomes dominant, it starts to secrete large amounts of estrogen. This sharp increase in estrogen causes positive feedback effects on the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, which results in a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH) and then ovulation. During the luteal phase, the postovulatory dominant ovarian follicle transforms into a corpus luteum, which in turn produces both progesterone and estrogen. The combination of these two ovarian hormones helps the endometrium thicken and become more vascular. If fertilization does not occur, the corpus luteum cannot survive. As the corpus luteum regresses, estrogen and progesterone levels drop and FSH begins to rise to initiate follicular growth for the next cycle.

Thus, the absolute levels of estrogen and progesterone, and the ratio of these hormone concentrations, change over the regular menstrual cycle. Both progesterone and estrogen levels are low during the early follicular phase, while the late follicular phase is characterized by a marked increase in secretion of estrogen. Finally, progesterone levels rise during the early luteal phase, peaking in the mid-luteal phase, in parallel with a second estrogen peak.

Research Examining Effects of Ovarian Hormones

Although estrogen and progesterone are best known for their effects on the female reproductive organs (e.g., uterus; ovary), they cross the blood-brain barrier (Henderson, 1997; Wirth, 2011) and affect brain functions as well (e.g., McEwen, 2002). For example, the hypothalamus, which plays an important role in regulation of the menstrual cycle (as described above), has both estrogen and progesterone receptors. Many other brain regions that are not crucial for reproduction also show progesterone receptor expression (Brinton et al., 2008), such as the amygdala, brainstem, hippocampus, cerebellum, and frontal cortex. Among those areas, the amygdala is a key region in emotional processing (e.g., Phelps, 2006). The amygdala also has both ERα and ERβ estrogen receptors (e.g., Weiser, Foradori, & Handa, 2008). In fact, the amygdala has one of the highest densities of estrogen receptors in the brain (Merchenthaler, Lane, Numan, & Dellovade, 2004; Shughrue & Merchenthaler, 2001). These findings suggest that both estrogen and progesterone influence reactions to emotional stimuli. In addition, other brain regions, such as the ventral tegmental area, hippocampus, and cerebellum, also express at least one of the estrogen receptors (McEwen, 2002; Weiser et al., 2008). Given that the ventral tegmental area plays a crucial role in processing of reward (Berridge, 2003; Berridge et al., 2009), females may show different responses to reward depending on the cycle.

To address these effects of the ovarian hormones in humans, past studies categorized the menstrual cycle into several phases and compared women's reactions to emotional or rewarding stimuli in one phase with other phases. Some studies distinguished the follicular vs. luteal phases. Given that both estrogen and progesterone levels are higher in the luteal than in the follicular phase on the average, however, these studies cannot discriminate the effects of estrogen and progesterone. Thus, other studies have defined menstrual phase more specifically, with smaller ranges of dates of testing. For example, studies examining the effects of estrogen compare females in the late follicular mid-cycle phase (high estrogen and low progesterone) with the early follicular phase (low estrogen and low progesterone). In contrast, studies addressing the effects of progesterone compare the luteal phase (high estrogen and high progesterone) vs. the late follicular phase (high estrogen and low progesterone). Furthermore, researchers sometimes administer progesterone or estrogen to females in the early follicular phase. The exogenous administration of the ovarian hormones seems especially useful to understand the role of progesterone independently from estrogen, because there is no phase involving low estrogen and high progesterone in the regular menstrual cycle.

The phases of the cycle have been defined in various ways. Some studies have relied on self-reports of the dates of menstruation. Other studies have identified the day of ovulation by having participants measure their body temperature or their urinary LH levels. Given possible individual differences and potential menstrual cycle variations within the same women (e.g., Alliende, 2002), these methods are sometimes combined with hormone assays based on plasma or saliva samples to verify the definition of the phase. While these methodological issues are important (see Terner & de Wit, 2006 for a related discussion), the field is new and the number of relevant studies is still small. Therefore, we review studies irrespective of the methods used to define and verify the cycle phases.

In the following sections, we first describe findings from past studies examining the effects of the menstrual cycle on reactions to rewards, and then findings on reactions to emotionally arousing stimuli in healthy women. Each section starts with reviewing previous studies that simply compared the follicular phase (days 1–14) and the luteal phase (days 15–28). To understand the roles of estrogen and progesterone, we then describe studies examining the effects of these hormones separately with finer cycle categorizations or exogenous administrations of the ovarian hormones.

Effects of Ovarian Hormones on Reactions to Reward

Females showed greater physiological and subjective effects of cocaine (Evans & Foltin, 2006; Evans, Haney, & Foltin, 2002), amphetamine (Justice & de Wit, 1999) and nicotine (Gray et al., 2010) during the follicular phase than during the luteal phase. Neuroimaging research also revealed that monetary reward induced greater activity in the striatum in the follicular than luteal phase (Dreher et al., 2007). However, it is not clear whether the decreased reactions to reward during the luteal phase were due to estrogen or progesterone, both of which are elevated in this period. To address this question, we review studies examining the effects of these hormones separately.

Estrogen Enhances Reactions to Reward

Animal studies suggest that estrogen enhances reactions to rewards (Becker & Hu, 2008; Lynch, Roth, & Carroll, 2002). In one study (Hu, Crombag, Robinson, & Becker, 2004), for example, female ovariectomized rats were given estrogen before self-administration sessions, in which they were allowed to nose poke to obtain a cocaine infusion. The results indicated that ovariectomized rats with estrogen self-administered larger amounts of cocaine more frequently than did ovariectomized rats without estrogen. Estrogen was also revealed to increase behavioral sensitization (Becker & Hu, 2008; Galankin, Shekunova, & Zvartau, 2010; Hu & Becker, 2003) and dopamine release in reward-related regions in the brain (e.g., striatum; Becker, 1990).

Studies in humans demonstrated similar enhancement effects of estrogen on reactions to rewards. When receiving doses of d-amphetamine, for instance, females reported that they liked the effects of drug more strongly in the late follicular phase (high estrogen and low progesterone) than the early follicular phase (low estrogen and low progesterone; Justice & De Wit, 2000a). In addition, exogenous estrogen administration to females with low progesterone increased subjective effects of d-amphetamine (e.g., "want more"; feeling "high"; Justice & de Wit, 2000b; Lile, Kendall, Babalonis, Martin, & Kelly, 2007). Taken together with findings from animal studies, it appears that estrogen enhances reactions to reward stimuli.

Progesterone Counters Facilitative Effects of Estrogen

However, estrogen no longer has facilitative effects on reactions to rewards when progesterone is high. As described in previous sections, estrogen administration to ovariectomized female rats increased self-administration of cocaine (e.g., Hu et al., 2004). When estrogen and progesterone were given together, however, progesterone diminished the facilitative effects of estrogen (Jackson, Robinson, & Becker, 2006; Larson, Anker, Gliddon, Fons, & Carroll, 2007). These results are consistent with recent findings that progesterone down-regulates the estrogen receptor (e.g,. Aguirre, Jayaraman, Pike, & Baudry, 2010), and suggest that progesterone counters the facilitative effects of estrogen (Anker, Larson, Gliddon, & Carroll, 2007; Quinones-Jenab & Jenab, 2010; Yang, Zhao, Hu, & Becker, 2007).

Studies in humans provide additional support that progesterone opposes the effects of estrogen. In line with the facilitative roles of estrogen, estrogen level was positively correlated with the magnitude of subjective (e.g., feeling "high"; elation) and physiological (e.g., heart rate) stimulation of amphetamine during the follicular phase (Justice & de Wit, 1999; White, Justice, & de Wit, 2002). But when progesterone was high (i.e., during the luteal phase), the level of estrogen no longer had a positive correlation with the magnitude of amphetamine’s stimulation (Justice & de Wit, 1999; White et al., 2002).

A recent neuroimaging study also reported consistent evidence (Frank, Kim, Krzemien, & Van Vugt, 2010). In this study, female participants viewed images of high-calorie-rewarding foods (e.g., cakes, cookies, ice cream) and of low-calorie foods (e.g., steamed vegetables) when they were hungry. During the late follicular phase, high-calorie foods induced greater activity in reward-related regions (e.g., nucleus accumbens) than did low-calorie foods. However, nucleus accumbens activity did not differ between high- and low-calorie foods in the luteal phase. Given the hormone patterns of the late follicular (high estrogen and low progesterone) and the luteal phase (high estrogen and high progesterone), these results seem consistent with the idea that progesterone counters facilitative effects of estrogen.

Progesterone Decreases Reactions to Reward by Itself

In addition to its countering effects on estrogen, past studies have revealed that progesterone can decrease reactions to reward even when estrogen is low (Evans, 2007; Quinones-Jenab & Jenab, 2010). While intact animals show strong preference for a chamber associated with cocaine, for example, progesterone administration diminished the preference for the cocaine-paired chambers in ovariectomized female rats (Russo et al., 2003) and in male rats (Romieu, Martin-Fardon, Bowen, & Maurice, 2003). Studies in humans also reported similar findings. When progesterone was administered to females with low estrogen, for instance, it attenuated physiological and subjective (e.g., feeling "high," "willing to pay") effects of cocaine (Evans & Foltin, 2006; Sofuoglu, Babb, & Hatsukami, 2002). Administration of progesterone also reduced urges to smoke cigarettes in female smokers during the early follicular phase (Sofuoglu, Mouratidis, & Mooney, 2011). Because those studies addressed the effects of progesterone when estrogen is low, they suggest that progesterone decreases reactions to rewards not only by countering the effects of estrogen, but also by itself.

Summary

In summary, it appears that estrogen and progesterone have opposing effects on reactions to rewards. That is, both animal and human studies indicate that estrogen enhances reactions to rewards. In contrast, studies suggest that progesterone counters the facilitative effects of estrogen and decreases reactions to rewards. As we described above, females tend to show stronger reactions to rewards during the follicular phase than during the luteal phase (Dreher et al., 2007; Evans & Foltin, 2006; Evans et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2010; Justice & de Wit, 1999; Sofuoglu, Dudish-Poulsen, Nelson, Pentel, & Hatsukami, 1999). Given studies reviewed in this section, it appears that progesterone is crucial to explain the decreased reward sensitivity during the luteal phase.

Effects of Ovarian Hormones on Reactions to Emotionally Negative Stimuli

Next, we turn to the question whether and how ovarian hormones influence reactions to emotionally arousing stimuli. As we mentioned above, emotional stimuli involve stimuli inducing physiological arousal, irrespective of whether they are positive or negative. However, the majority of past studies on ovarian hormones employed only negative and neutral stimuli. Therefore, we focus on findings about reactions to negative stimuli in this section.

As with reward, previous studies revealed that females react to emotionally negative stimuli differently in follicular vs. luteal phases. Compared with the follicular phase, for example, females in the luteal phase showed increased stress hormones after stressful tasks (Altemus, Roca, Galliven, Romanos, & Deuster, 2001; Childs, Dlugos, & De Wit, 2010; Kirschbaum, Kudielka, Gaab, Schommer, & Hellhammer, 1999; Roca et al., 2003; Tersman, Collins, & Eneroth, 1991), showed stronger amygdala activity when anticipating pain (Choi et al., 2006), and interpreted mildly negative faces as strongly negative (Derntl, Kryspin-Exner, Fernbach, Moser, & Habel, 2008). Studies of daily moods also reported increased negative moods during the luteal phase than the follicular phase (Allen, Allen, & Pomerleau, 2009; Reed, Levin, & Evans, 2008; Sanders, Warner, Backstrom, & Bancroft, 1983). Because these studies cannot discriminate the effects of the two ovarian hormones, we review studies examining estrogen and progesterone separately in the following sections.

Estrogen Decreases Reactions to Emotionally Negative Stimuli

Animal studies indicate estrogen decreases reactions to emotionally negative stimuli. For example, exogeneous estrogen administration decreases release of stress hormones at least when estrogen does not reach supra-physiological levels (Dayas, Xu, Buller, & Day, 2000; Young, Altemus, Parkison, & Shastry, 2001). Estrogen administration to ovariectomized female rats also increased time spent in open arms in the elevated plus maze (an aversive situation for a rat) and reduced duration of freezing after foot-shock (Frye & Walf, 2004), thus reducing the intensity of anxious or depressive responses to aversive situations (Walf & Frye, 2006).

Similar patterns were observed in studies in humans as well (e.g., Gasbarri et al., 2008). Higher levels of estrogen were associated with poorer performance in recognizing anger faces (Guapo et al., 2009). Estrogen therapy is also known to decrease depressive symptoms at least in perimenopausal females (Cohen et al., 2003; Soares, Almeida, Joffe, & Cohen, 2001). Furthermore, Goldstein et al. (2005) compared brain activity while viewing negative or neutral pictures during the early follicular (low estrogen and low progesterone) vs. late follicular phase (high estrogen and low progesterone). As shown in previous studies collapsing sex and menstrual cycle phases (e.g., Ochsner et al., 2004; Phan et al., 2002), females in both phases showed enhanced activity in emotion related regions, such as the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), when viewing negative pictures than neutral pictures. However, the activity of these areas was modulated by the menstrual cycle phases. That is, females showed greater activity in the amygdala and OFC to negative pictures during the early follicular phase than during the late follicular phase (see also Goldstein, Jerram, Abbs, Whitfield-Gabrieli, & Makris, 2010).

Thus, both animal and human studies suggest that reactions to negative stimuli are decreased by estrogen. Although different studies employed different tasks or measures (e.g., amygdala activity to negative pictures, facial emotion recognition), they have observed consistent patterns, suggesting that estrogen has similar effects across different aspects of reactions to negative stimuli. However, this does not mean that estrogen inhibits any tasks involving negative stimuli. In fact, recent research has revealed the facilitative effects of estrogen on one type of learning involving negative stimuli -- extinction of fear conditioning (Milad, Igoe, Lebron-Milad, & Novales, 2009; Milad et al., 2010; Zeidan et al., in press).

One possible factor contributing to the contradictory findings is the complexity of tasks being employed. While studies showing inhibitory effects of estrogen measured relatively simple reactions to negative stimuli (e.g., amygdala activity to negative pictures; facial emotion recognition), extinction learning requires multiple types of processing. For instance, recent research indicates that extinction of fear conditioning involves reward-related learning (Holtzman-Assif, Laurent, & Westbrook, 2010; Raczka et al., 2011). Thus, the facilitative effects of estrogen on extinction recall might be caused by the effects of estrogen on reward. Furthermore, hippocampal structure is changed by estrogen quite rapidly. For example, higher levels of estrogen result in greater synapse density of hippocampus within 24 hours in rats (Woolley & McEwen, 1993). Research in humans also revealed that the same women had increased hippocampal volume during the late-follicular phase than the premenstrual phase (Protopopescu et al., 2008). Since extinction of conditioning depends not only on emotion-related areas (e.g., OFC), but also on the hippocampus (Milad et al., 2007), structural changes in brain regions critical for extinction learning may also explain enhancing effects of estrogen on extinction. Taken together, it appears that estrogen decreases reactions to negative stimuli, but can have facilitative effects when tasks involve reward-related components or hippocampus-related processing.

Progesterone Enhances Reactions to Emotionally Negative Stimuli

In contrast with estrogen's inhibitory effects on reactions to negative stimuli, past studies suggested that progesterone enhances reactions to negative stimuli at least in humans (e.g., Andreano, Arjomandi, & Cahill, 2008; Protopopescu et al., 2005). When females were tested at two timepoints with different level of progesterone, for example, they experienced more spontaneous intrusive recollections about unpleasant events when progesterone was high than when progesterone was low (Ferree & Cahill, 2009; Ferree, Kamat, & Cahill, in press). Similarly, compared to the late follicular phase (high estrogen and low progesterone), females in the luteal phase (high estrogen and high progesterone) were more sensitive to facial cues signaling contagion and physical threat (Conway et al., 2007) and increased their heart rates more while watching negative videos (Ossewaarde et al., 2010). Furthermore, a neuroimaging study (Andreano & Cahill, 2010) revealed increased amygdala activity to negative pictures (relative to neutral pictures) when progesterone was high than when progesterone was low.

Human studies employing exogenous progesterone administration also confirmed the facilitative role of progesterone. For example, females in the follicular phase showed increased amygdala activity to angry and fearful faces when they were given progesterone compared with placebo (van Wingen et al., 2008). Progesterone administration also increased physiological reactions to a stress task both in males (Childs, Van Dam, & Wit, 2010) and females (Roca et al., 2003). Furthermore, exogenous progesterone increased negative moods in women in the early follicular phase (Klatzkin, Leslie Morrow, Light, Pedersen, & Girdler, 2006; Soderpalm, Lindsey, Purdy, Hauger, & de Wit, 2004) as well as in postmenopausal women (Andréen et al., 2009). Taken together, it appears that progesterone increases reactions to negative stimuli in humans.

However, animal studies provided contradictory findings (Wirth, 2011). That is, exogeneous progesterone administration was revealed to decrease the intensity of anxious or depressive responses to aversive situations (e.g., elevated plus maze, foot-shock; Auger & Forbes-Lorman, 2008; Frye & Walf, 2004; Llaneza & Frye, 2009). Furthermore, some studies in humans also observed that progesterone administration weakened subjective reactions to negative stimuli (e.g., Childs, Van Dam et al., 2010; de Wit, Schmitt, Purdy, & Hauger, 2001).

One possible reason for this inconsistency is that while increases in progesterone seen during normal menstrual cycles enhance reactions to negative stimuli (as we discussed above), concentrations of progesterone higher than the normal range might decrease emotional reactions and have calming effects (see Andréen et al., 2009 for a review). In fact, when progesterone was administered to post menopausal women, participants reported the highest negative mood scores with a moderate level of oral micronized progesterone (Andréen, Sundström-Poromaa, Bixo, Nyberg, & Bäckström, 2006). In contrast, both lower and higher concentrations of progesterone produced less negative moods (Andréen et al., 2006). Thus, it appears that the effects of progesterone follow an inverse-U function, rather than a linear correlation. Perhaps, if there is too much progesterone, progesterone no longer has facilitative effects and decreases reactions to negative stimuli (see also Andréen et al., 2005; Gomez, Saldivar-Gonzalez, Delgado, & Rodriguez, 2002). This might explain why studies with exogenous progesterone administration to animals and humans sometimes revealed inhibitory effects of progesterone on reactions to negative stimuli.

Summary

Studies reviewed in this section indicate that estrogen and progesterone have opposing influences on reactions to emotionally negative stimuli. In other words, reactions to negative stimuli appear to be decreased by estrogen but enhanced by progesterone. These patterns were observed across different studies employing different types of tasks or measures (e.g., amygdala activity to negative pictures; stress hormones; facial emotion recognition). However, studies sometimes observed different patterns. Potential factors for these inconsistencies are an inverse quadratic function of progesterone’s effects, reward-related components involved in tasks being employed, and structural changes of the brain across the menstrual cycle.

Effects of Ovarian Hormones on Reactions to Emotionally Positive Stimuli

The amygdala, a key region for emotional processing, responds to emotionally arousing information, regardless of whether it is positive or negative (e.g., Anderson et al., 2003; Kensinger & Schacter, 2006; Sergerie, Chochol, & Armony, 2008). Thus, one might expect that estrogen and progesterone have similar influences on positive and negative stimuli. However, previous studies in humans provided mixed results regarding ovarian hormone effects on reactions to positive stimuli.

Consistent with facilitative effects of progesterone on reactions to negative stimuli, for example, progesterone administration increased positive emotional states in postmenopausal women (de Wit et al., 2001). Higher progesterone was also associated with a greater increase in cortisol after positive emotion induction in males (Wirth, Meier, Fredrickson, & Schultheiss, 2007). However, opposite patterns have also been reported. That is, progesterone administration reduced amygdala activity to happy or neutral faces (van Wingen et al., 2007) and decreased positive emotional states, such as friendliness or confidence, in females in the early follicular phase (de Wit et al., 2001; Klatzkin et al., 2006). Results on estrogen were also mixed. Researchers sometimes observed increased activity in emotion-related areas to positive stimuli when estrogen was low than high (Zhu et al., 2010). However, other research provided evidence for facilitative effects of estrogen on reactions to positive stimuli (Amin, Epperson, Constable, & Canli, 2006; Gizewski et al., 2006).

One possible reason for this inconsistency is the role of reward. Although rewards and emotionally positive stimuli can be defined separately (as discussed above), they also overlap with each other. For example, positive but non-rewarding stimuli activate reward-related regions, such as striatum, in addition to the amygdala (Hamann & Mao, 2002). Recent research also revealed that viewing positive emotional stimuli can increase subsequent striatum activity to monetary rewards (Wittmann, Schiltz, Boehler, & Duzel, 2008). These results suggest that positive emotional stimuli not only evoke emotional arousal, but also prime reward-related processing.

This complex nature of positive stimuli might explain the mixed findings of estrogen and progesterone on reactions to positive stimuli. That is, estrogen might facilitate reward-related aspects of reactions to positive stimuli, but decrease their aspects related to emotional arousal. Similarly, progesterone might decrease reward-related aspects of reactions to positive stimuli, but have facilitative effects on their aspects related to emotional arousal. Thus, ovarian hormones might have opposing influences on the reward-related and arousal-related aspects of positive emotion, which could result in unclear effects of the ovarian hormones on reactions to positive stimuli.

Questions for Future Research and Conclusions

In summary, the current paper suggests that estrogen and progesterone have opposing influences on both reactions to emotionally arousing negative stimuli and reactions to rewarding stimuli. In other words, reactions to negative stimuli seem to be decreased by estrogen, but enhanced by progesterone. In contrast, the opposite effects were observed in reactions to rewarding stimuli. That is, it appears that estrogen enhances reactions to rewards, while progesterone decreases reactions to rewards not only by itself, but also by countering the facilitative effects of estrogen. In addition to this overall pattern, the current paper also highlights several important questions for future studies.

The first question concerns the effects of the ovarian hormones on reactions to positive stimuli. As we pointed out in the previous section, past studies reported mixed findings on the effects of estrogen and progesterone on reactions to positive stimuli. Given a potential link between reward and positive emotion (e.g., Wittmann et al., 2008), reactions to positive stimuli might reflect not only emotional arousal-related processing, but also reward-related processing. Future studies should tease apart these two aspects of positive emotion to clarify how the ovarian hormones modulate reactions to positive stimuli.

A second question is which aspects of reward and emotion are affected by estrogen and progesterone. Reward is not a unitary concept and has been decomposed into two aspects (Berridge & Robinson, 2003; Berridge et al., 2009): a) hedonic consequences of consumption ('liking') and b) incentive salience (i.e., 'wanting'; craving). Studies reviewed in this paper demonstrated similar effects of estrogen and progesterone on these two aspects. That is, incentive salience (e.g., "want more") is enhanced by estrogen (e.g., Justice & de Wit, 2000b), but decreased by progesterone (Gray et al., 2010). Hedonic consequences (e.g., "like drug") is also enhanced by estrogen (e.g., Justice & De Wit, 2000a), but decreased by progesterone (e.g., Evans & Foltin, 2006). However, these two aspects often correlate with each other (e.g., Epstein et al., 2004). Thus, it is possible that the ovarian hormones influence only one of the aspects, and that the affected aspect modulates the other aspect, which results in similar patterns between them. Likewise, although previous research on negative emotion observed similar effects of the ovarian hormones across different aspects of emotional reactions (e.g., amygdala activity; stress hormone, subjective mood states), there might be some aspects that are more strongly modulated by ovarian hormones than others. Future studies need to clarify which aspects of emotional and reward reactions are modulated by the ovarian hormones, while considering detailed neurobiological mechanisms of the influences of estrogen and progesterone (e.g., Hudson & Stamp, 2011; Quinones-Jenab & Jenab, 2010).

Another question for future research is how ovarian hormones influence social behaviors or one's personality. The construct of personality relies on the assumption that individuals can be characterized by qualities that are relatively invariant over time. However, many personality traits are related with emotion or rewards (e.g., trait anxiety, neuroticism, self-esteem, and reward sensitivity). Thus, the same woman might show cyclic variations in their emotion-related or reward-related personality tendencies. Similarly, the ovarian hormones might influence within-individual processes and social behaviors, such as emotion regulation, well-being, consumption behaviors, and attitudes toward other people, all of which are relevant to emotion or reward. Future studies need to address the effects of the ovarian hormones on those complex intra- and inter-personal processes, while combining traditional psychology research methods (e.g., personality assessment, behavioral experiment), with physiological measures (e.g., hormone assay) and neuroimaging methods. This multimethodological approach should provide better understanding of our behaviors in everyday life.

In conclusion, from the studies included in this review, it appears that the menstrual cycle and ovarian hormones modulate how people react to emotional and rewarding stimuli. Given the core importance of emotion and reward processing in our lives, such differences are important and further investigation is needed to better understand the mechanisms of the effects. These hormonal effects might explain why specific phases of the cycle are related to depressive symptoms (Farage, Osborn, & MacLean, 2008) or higher risks in addiction (Becker & Hu, 2008; Terner & de Wit, 2006). Thus, examining the effects of menstrual cycle or ovarian hormones may have theoretical implications in many fields, while providing practical suggestions on how to improve females’ well-being in real life.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants K02 AG032309, R01 AG025340, and R01 AG038043.

References

- Aguirre C, Jayaraman A, Pike CJ, Baudry M. Progesterone inhibits estrogen-mediated neuroprotection against excitotoxicity by down-regulating estrogen receptor-β. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(5):1277–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SS, Allen AM, Pomerleau CS. Influence of phase-related variability in premenstrual symptomatology, mood, smoking withdrawal, and smoking behavior during ad libitum smoking, on smoking cessation outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(1):107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliende ME. Mean versus individual hormonal profiles in the menstrual cycle. Fertility and Sterility. 2002;78(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemus M, Roca CA, Galliven E, Romanos C, Deuster P. Increased vasopressin and adrenocorticotropin responses to stress in the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86(6):2525–2530. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin Z, Epperson CN, Constable RT, Canli T. Effects of estrogen variation on neural correlates of emotional response inhibition. NeuroImage. 2006;32(1):457–464. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AK, Christoff K, Stappen I, Panitz D, Ghahremani DG, Glover G, et al. Dissociated neural representations of intensity and valence in human olfaction. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6(2):196–202. doi: 10.1038/nn1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréen L, Nyberg S, Turkmen S, van Wingen GA, Fernández G, Bäckström T. Sex steroid induced negative mood may be explained by the paradoxical effect mediated by gabaa modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(8):1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréen L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Andersson A, Nyberg S, Bäckström T. Relationship between allopregnanolone and negative mood in postmenopausal women taking sequential hormone replacement therapy with vaginal progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(2):212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréen L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Bixo M, Nyberg S, Bäckström T. Allopregnanolone concentration and mood—a bimodal association in postmenopausal women treated with oral progesterone. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187(2):209–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreano JM, Arjomandi H, Cahill L. Menstrual cycle modulation of the relationship between cortisol and long-term memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreano JM, Cahill L. Sex influences on the neurobiology of learning and memory. Learning & Memory. 2009;16(4):248–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.918309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreano JM, Cahill L. Menstrual cycle modulation of medial temporal activity evoked by negative emotion. NeuroImage. 2010;53(4):1286. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Larson EB, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Effects of progesterone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in female rats. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2007;15(5):472–472. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.472. 480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger CJ, Forbes-Lorman RM. Progestin receptor-mediated reduction of anxiety-like behavior in male rats. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr SI. Vegetarianism and menstrual cycle disturbances: Is there an association? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;70(3):549S–554S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.549S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB. Estrogen rapidly potentiates amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine release and rotational behavior during microdialysis. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;118(2):169–171. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90618-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Hu M. Sex differences in drug abuse. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2008;29(1):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. Pleasures of the brain. Brain and Cognition. 2003;52:106–128. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26(9):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: `liking', `wanting', and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, Baudry M, Wang J, Finch CE, et al. Progesterone receptors: Form and function in brain. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2008;29(2):313–339. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L. Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(6):477–484. doi: 10.1038/nrn1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldú X, Dreher J-C. Hormonal and genetic influences on processing reward and social information. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1118(1):43–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1412.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camara E, Rodriguez-Fornells A, Munte TF. Functional connectivity of reward processing in the brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2009;2 doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.019.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, Dlugos A, De Wit H. Cardiovascular, hormonal, and emotional responses to the tsst in relation to sex and menstrual cycle phase. Psychophysiology. 2010;47(3):550–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, Van Dam NT, Wit H. Effects of acute progesterone administration upon responses to acute psychosocial stress in men. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2010;18(1):78–86. doi: 10.1037/a0018060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JC, Park SK, Kim YH, Shin YW, Kwon JS, Kim JS, et al. Different brain activation patterns to pain and pain-related unpleasantness during the menstrual cycle. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(1):120–127. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Soares CN, Poitras JR, Prouty J, Alexander AB, Shifren JL. Short-term use of estradiol for depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: A preliminary report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1519–1522. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway CA, Jones BC, DeBruine LM, Welling LLM, Law Smith MJ, Perrett DI, et al. Salience of emotional displays of danger and contagion in faces is enhanced when progesterone levels are raised. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;51(2):202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas CV, Xu Y, Buller KM, Day TA. Effects of chronic oestrogen replacement on stress-induced activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis control pathways. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12(8):784–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Schmitt L, Purdy RH, Hauger R. Effects of acute progesterone administration in healthy postmenopausal women and normally-cycling women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26(7):697–710. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derntl B, Kryspin-Exner I, Fernbach E, Moser E, Habel U. Emotion recognition accuracy in healthy young females is associated with cycle phase. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;53(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher J-C, Schmidt PJ, Kohn P, Furman D, Rubinow D, Berman KF. Menstrual cycle phase modulates reward-related neural function in women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(7):2465–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605569104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Wright SM, Paluch RA, Leddy J, Hawk LW, Jaroni JL, et al. Food hedonics and reinforcement as determinants of laboratory food intake in smokers. Physiology & Behavior. 2004;81(3):511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM. The role of estradiol and progesterone in modulating the subjective effects of stimulants in humans. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2007;15(5):418–426. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Foltin RW. Exogenous progesterone attenuates the subjective effects of smoked cocaine in women, but not in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(3):659–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Haney M, Foltin RW. The effects of smoked cocaine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology. 2002;159:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage M, Osborn T, MacLean A. Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: A review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2008;278(4):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree NK, Cahill L. Post-event spontaneous intrusive recollections and strength of memory for emotional events in men and women. Consciousness and Cognition. 2009;18(1):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree NK, Kamat R, Cahill L. Influences of menstrual cycle position and sex hormone levels on spontaneous intrusive recollections following emotional stimuli. Consciousness and Cognition, In Press, Corrected Proof. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.02.003. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank TC, Kim GL, Krzemien A, Van Vugt DA. Effect of menstrual cycle phase on corticolimbic brain activation by visual food cues. Brain Research. 2010;1363:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Walf AA. Estrogen and/or progesterone administered systemically or to the amygdala can have anxiety-, fear-, and pain-reducing effects in ovariectomized rats. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118(2):306–313. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galankin T, Shekunova E, Zvartau E. Estradiol lowers intracranial self-stimulation thresholds and enhances cocaine facilitation of intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;58(5):827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbarri A, Pompili A, d'Onofrio A, Cifariello A, Tavares MC, Tomaz C. Working memory for emotional facial expressions: Role of the estrogen in young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(7):964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizewski E, Krause E, Karama S, Baars A, Senf W, Forsting M. There are differences in cerebral activation between females in distinct menstrual phases during viewing of erotic stimuli: A fMRI study. Experimental Brain Research. 2006;174(1):101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Abbs B, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Makris N. Sex differences in stress response circuitry activation dependent on female hormonal cycle. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(2):431–438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3021-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, et al. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(40):9309–9316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C, Saldivar-Gonzalez A, Delgado G, Rodriguez R. Rapid anxiolytic activity of progesterone and pregnanolone in male rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;72(3):543–550. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00722-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, DeSantis SM, Carpenter MJ, Saladin ME, LaRowe SD, Upadhyaya HP. Menstrual cycle and cue reactivity in women smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(2):174–178. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Canli T. Individual differences in emotion processing. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2004;14(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Mao H. Positive and negative emotional verbal stimuli elicit activity in the left amygdala. Neuroreport. 2002;13:15–19. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200201210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson VW. The epidemiology of estrogen replacement therapy and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1997;48(5 Suppl 7):S27–S35. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_7.27s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Becker JB. Effects of sex and estrogen on behavioral sensitization to cocaine in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(2):693–699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00693.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Crombag HS, Robinson TE, Becker JB. Biological basis of sex differences in the propensity to self-administer cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(1):81–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson A, Stamp JA. Ovarian hormones and propensity to drug relapse: A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;35(3):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LR, Robinson TE, Becker JB. Sex differences and hormonal influences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(1):129–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AJH, de Wit H. Acute effects of d-amphetamine during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Psychopharmacology. 1999;145(1):67–75. doi: 10.1007/s002130051033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AJH, De Wit H. Acute effects of d-amphetamine during the early and late follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000a;66(3):509–515. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice AJH, de Wit H. Acute effects of estradiol pretreatment on the response to d-amphetamine in women. Neuroendocrinology. 2000b;71(1):51–59. doi: 10.1159/000054520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, Phillips DIW. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(2):151–178. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Two routs to emotional memory: Distinct neural processes for valence and arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2004;101(9):3310–3315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306408101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Processing emotional pictures and words: Effects of valence and arousal. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;6:110–126. doi: 10.3758/cabn.6.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka B, Gaab J, Schommer N, Hellhammer D. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61(2):154–162. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzkin RR, Leslie Morrow A, Light KC, Pedersen CA, Girdler SS. Associations of histories of depression and pmdd diagnosis with allopregnanolone concentrations following the oral administration of micronized progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(10):1208–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML. The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:691–702. doi: 10.1038/nrn1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in hpa axis responses to stress: A review. Biological Psychology. 2005;69(1):113–132. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, Anker JJ, Gliddon LA, Fons KS, Carroll ME. Effects of estrogen and progesterone on the escalation of cocaine self-administration in female rats during extended access. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2007;15(5):461–471. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Kendall SL, Babalonis S, Martin CA, Kelly TH. Evaluation of estradiol administration on the discriminative-stimulus and subject-rated effects of d-amphetamine in healthy pre-menopausal women. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;87(2):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llaneza DC, Frye CA. Progestogens and estrogen influence impulsive burying and avoidant freezing behavior of naturally cycling and ovariectomized rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93(3):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Carroll ME. Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: Preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology. 2002;164(2):121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Sutherland M. Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:114–133. doi: 10.1177/1745691611400234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. Estrogen actions throughout the brain. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 2002;57(1):357–384. doi: 10.1210/rp.57.1.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchenthaler I, Lane MV, Numan S, Dellovade TL. Distribution of estrogen receptor α and β in the mouse central nervous system: In vivo autoradiographic and immunocytochemical analyses. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2004;473(2):270–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Knierim K, Ludlow DH, Hanelin J, Ramachandran T, Glover G, et al. Reflecting upon feelings: An fMRI study of neural systems supporting the attribution of emotion to self and other. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16(10):1746–1772. doi: 10.1162/0898929042947829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde L, Hermans EJ, van Wingen GA, Kooijman SC, Johansson I-M, Bäckström T, et al. Neural mechanisms underlying changes in stress-sensitivity across the menstrual cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Wager T, Taylor SF, Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: A meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in pet and fMRI. Neuroimage. 2002;16(2):331–348. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA. Emotion and cognition: Insights from studies of the human amygdala. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:27–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, LeDoux JE. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron. 2005;48(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu X, Butler T, Pan H, Root J, Altemus M, Polanecsky M, et al. Hippocampal structural changes across the menstrual cycle. Hippocampus. 2008;18(10):985–988. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protopopescu X, Pan H, Altemus M, Tuescher O, Polanecsky M, McEwen B, et al. Orbitofrontal cortex activity related to emotional processing changes across the menstrual cycle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(44):16060–16065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502818102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Jenab V, Jenab S. Progesterone attenuates cocaine-induced responses. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;58(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven P, Johnson G, Singer S, Losos J. Biology. 7th ed. New York: NY: McGraw-Hill Science; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Levin FR, Evans SM. Changes in mood, cognitive performance and appetite in the late luteal and follicular phases of the menstrual cycle in women with and without pmdd (premenstrual dysphoric disorder) Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54(1):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsza ME. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Pediatrics in Review. 2002;23(7):227–233. doi: 10.1542/pir.23-7-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Altemus M, Deuster P, Danaceau MA, Putnam K, et al. Differential menstrual cycle regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with premenstrual syndrome and controls. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2003;88(7):3057–3063. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu P, Martin-Fardon R, Bowen WD, Maurice T. Sigma1 receptor-related neuroactive steroids modulate cocaine-induced reward. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(9):3572–3576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03572.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Carroll JM. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(1):3–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Festa ED, Fabian SJ, Gazi FM, Kraish M, Jenab S, et al. Gonadal hormones differentially modulate cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in male and female rats. Neuroscience. 2003;120(2):523–533. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders D, Warner P, Backstrom T, Bancroft J. Mood, sexuality, hormones and the menstrual cycle I. Changes in mood and physical state: Description of subjects and method. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1983;45(6):487–501. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergerie K, Chochol C, Armony JL. The role of the amygdala in emotional processing: A quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(4):811–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabel SJ, Janak PH. Substantial similarity in amygdala neuronal activity during conditioned appetitive and aversive emotional arousal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(35):15031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905580106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I. Distribution of estrogen receptor β immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2001;436(1):64–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares DC, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):529–534. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderpalm AHV, Lindsey S, Purdy RH, Hauger R, de Wit H. Administration of progesterone produces mild sedative-like effects in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(3):339–354. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Babb DA, Hatsukami DK. Effects of progesterone treatment on smoked cocaine response in women. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;72(1–2):431–435. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Dudish-Poulsen S, Nelson D, Pentel PR, Hatsukami DK. Sex and menstrual cycle differences in the subjective effects from smoked cocaine in humans. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 1999;7(3):274. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Mouratidis M, Mooney M. Progesterone improves cognitive performance and attenuates smoking urges in abstinent smokers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(1):123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terner JM, de Wit H. Menstrual cycle phase and responses to drugs of abuse in humans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tersman Z, Collins A, Eneroth P. Cardiovascular responses to psychological and physiological stressors during the menstrual cycle. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53(2):185–197. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wingen GA, van Broekhoven F, Verkes RJ, Petersson KM, Backstrom T, Buitelaar JK, et al. How progesterone impairs memory for biologically salient stimuli in healthy young women. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(42):11416–11423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1715-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wingen GA, van Broekhoven F, Verkes RJ, Petersson KM, Backstrom T, Buitelaar JK, et al. Progesterone selectively increases amygdala reactivity in women. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):325–333. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(6):1097–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser MJ, Foradori CD, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor beta in the brain: From form to function. Brain Research Reviews. 2008;57(2):309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TL, Justice AJH, de Wit H. Differential subjective effects of d-amphetamine by gender, hormone levels and menstrual cycle phase. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;73(4):729–741. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, Gottfried JA, Kilner JM, Dolan RJ. Integrated neural representations of odor intensity and affective valence in human amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(39):8903–8907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MM. Beyond the hpa axis: Progesterone-derived neuroactive steroids in human stress and emotion. [Review] Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2011;2:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth MM, Meier EA, Fredrickson BL, Schultheiss OC. Relationship between salivary cortisol and progesterone levels in humans. Biological Psychology. 2007;74(1):104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann BC, Schiltz K, Boehler CN, Duzel E. Mesolimbic interaction of emotional valence and reward improves memory formation. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(4):1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1993;336(2):293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Zhao W, Hu M, Becker JB. Interactions among ovarian hormones and time of testing on behavioral sensitization and cocaine self-administration. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;184(2):174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Altemus M, Parkison V, Shastry S. Effects of estrogen antagonists and agonists on the acth response to restraint stress in female rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(6):881–891. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Wang X, Parkinson C, Cai C, Gao S, Hu P. Brain activation evoked by erotic films varies with different menstrual phases: An fMRI study. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;206(2):279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]