Abstract

Objective

We previously conducted the School Based Asthma Therapy trial to improve adherence to national asthma guidelines for urban children through directly observed administration of preventive asthma medications in school. The trial successfully improved outcomes among these children; however several factors limit its potential for dissemination. To enhance sustainability, we subsequently developed a new model of care using web-based guides for efficient communications and integration within school and community systems. This paper describes the development of the School-Based Preventive Asthma Care Technology (SB-PACT) trial.

Method

We developed the SB-PACT web-based system based on stakeholder feedback, and conducted a pilot randomized trial with 100 children to establish its feasibility in facilitating preventive asthma care for high-risk children. The SB-PACT system represents a new model of care using web-based guides for asthma symptom screening, follow-up control assessments, and electronic communications with providers.

Result

We enrolled and successfully screened all children using the web-based system. Most providers used the electronic communication system without difficulty, and the majority of children in the intervention group received preventive medications through school as planned and dose adjustments as needed. Several challenges to implementation also were encountered.

Conclusion

This program is designed to promote sustainability of school-based asthma care, reduce program costs, and to ultimately succeed in a real-world setting. With further refinements, it has the potential to be implemented nationally in schools.

Keywords: asthma, school-based, technology, sustainability, preventive care

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is one of the most common chronic illnesses of childhood, affecting nearly 10% of all children under the age of 18 in the United States.1 National guidelines established by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) recommend that all patients with persistent asthma receive a daily preventive, anti-inflammatory medication.2 These medications reduce symptoms and prevent hospitalizations when used as recommended. However, many children who should be using preventive medications are not, and inadequate therapy is most common among underserved minority populations.3,4 In addition, many children who are prescribed a preventive medication have poor adherence and subsequently do not achieve optimal control.4 Thus a significant amount of asthma morbidity could be prevented. Interventions to improve morbidity outcomes in this disadvantaged population are critically needed. Ease of implementation, generalizability and sustainability are key to the development of such approaches.

In response to the need for improved adherence to preventive asthma care guidelines, we previously conducted the School Based Asthma Therapy (SBAT) trial (2006–2009) with the aim of promoting guideline-based asthma care and reducing morbidity for poor and minority children with persistent symptoms.5 We enrolled 530 children, aged 3–10 years, with persistent asthma who attended a Rochester City School District (RCSD) elementary school or preschool in Rochester, NY. Children randomly assigned to the intervention group received daily preventive asthma medications administered as directly observed therapy (DOT) by school health staff, as well as ongoing assessment of symptoms and guideline-based adjustments in therapy, if needed. Thus, we could assure adherence to preventive medications on the days in which the child attended school. We found that children in the intervention group experienced significantly more symptom-free days than children receiving usual care. Children receiving the intervention also experienced significantly fewer nights with asthma symptoms and fewer days with rescue medication use.6 Details of this study are presented elsewhere.5

We concluded that the school-based asthma therapy program could significantly reduce asthma symptoms and serve as a model for improved asthma care in urban communities in the United States. However, we found that in its current form several facets of the research intervention limit its sustainability and broad dissemination. The program was relatively labor intensive and incurred significant personnel and medication costs. First, children were screened for eligibility (persistent asthma symptoms) by study team members and primary care providers (PCPs) were contacted for permission for the child’s enrollment. Despite using school-based health forms to help identify potentially eligible students, the screening process required many study personnel hours to make telephone contact with families and to communicate with PCPs. With modern technological advances, this system of screening and notification could be automated and coordinated through the schools.

Further, after enrollment in SBAT, we purchased medications through study funds and hand-delivered them to schools and to families’ homes for administration. When adjustments to therapy were needed, medications were again hand-delivered by the team. This method is labor intensive and difficult to sustain. In an ideal setting, many of these steps could occur with fewer resources, and medication costs could be covered by the child’s medical insurance; however, a mechanism is needed for this to occur systematically and efficiently.

We have learned from prior work that it is not effective to rely on families to self-identify children with persistent symptoms without systematic screening, since many caregivers underestimate asthma severity and overestimate level of control.7 Further, it is difficult for families to coordinate getting medications to the school health staff, or even to pick up their own prescriptions for home, in part due to the stressful and chaotic social conditions that often accompany the lives of inner-city families. In fact, many children in our prior studies did not even have a rescue medication available at school, despite having significant and recurring asthma symptoms.

In response to these program limitations, we developed and pilot tested the School-Based Preventive Asthma Care Technology (SB-PACT) program (1RC1HL099432) to build upon the successes of the previous trial. The goal of this new model of care was to use technologically simple web-based guides to overcome barriers to sustainability in a cost-effective and easily disseminable manner. Our unique partnership with the Rochester City School District provides us an ideal setting to test this system with the potential to disseminate the program to other school districts in similar communities. The SB-PACT trial incorporates web-based technology to systematically assess children’s asthma symptoms and generate reports, and an Asthma Care Coordinator (ACC) to facilitate communication between school health staff, healthcare providers and caregivers of children with asthma. For this new program, we have also integrated electronic physician authorization for medications, which are purchased through the child’s own health insurance and delivered directly to schools and children’s homes by the pharmacy. These measures were designed to promote sustainability, reduce program costs, and begin to transition this program to succeed in a real-world setting. This paper describes the methodology and development of the SB-PACT program, as well challenges encountered with program implementation.

METHODS

Study Design

To test the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of this new system of care, we conducted a pilot randomized control trial with 3–10 year old children from preschools and elementary schools in the Rochester City School District. Inclusion criteria required all children to have physician diagnosed asthma with persistent symptoms based on NHLBI guidelines. Families of children with other significant medical conditions that could interfere with the assessment of asthma-related outcomes were excluded. After a baseline assessment, children were randomly assigned into either the SB-PACT intervention group or a usual care comparison group. All children were followed systematically throughout the school year to assess outcomes by research staff, who were not involved in enrollment and were blinded to treatment allocation. The University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Overview of the SB-PACT Program

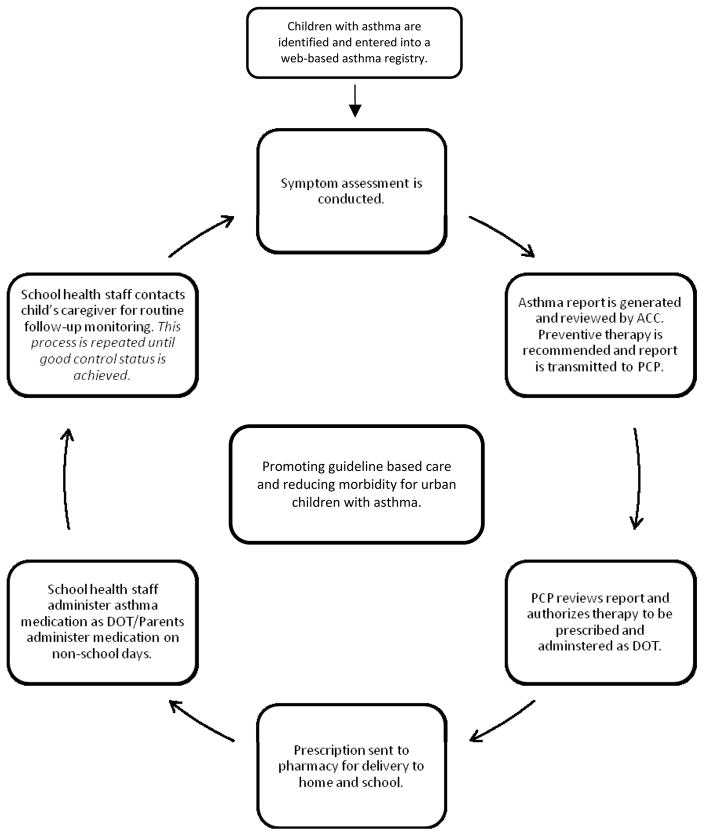

Figure 1 illustrates the steps included in the SB-PACT intervention. Each step is represented as part of a cycle with the goal of promoting guideline-based care and reducing morbidity. The steps included in the SB-PACT program are as follows:

Figure 1.

SB-PACT Flow Diagra

Identification of Children: School health staff identify children with asthma via school health forms and enter them into a web-based asthma registry.

Symptom Assessment: School health staff contact the child’s caregiver to conduct a symptom assessment using the screening tools in the web-based system.

Asthma Report Generation: If a child has persistent symptoms or poor asthma control, a trained Asthma Care Coordinator (ACC) reviews a summary report of the child’s symptoms. The ACC submits an Asthma Report and guideline-based therapy recommendations through the web application to the child’s PCP.

Authorization of Therapy: The PCP reviews the Asthma Report and authorizes therapy to be prescribed and administered as directly observed therapy (DOT) at school via the web-based Authorization Tool.

Delivery of Medications: Once authorized, the ACC sends a prescription to a local pharmacy on the PCP’s behalf to be delivered to the child’s home and school. School health staff administer preventive asthma medication as DOT on days the child attends school. Caregivers are instructed to administer the medication to their child on non-school days.

Symptom Reassessment: According to NHLBI guidelines for follow-up monitoring, school health staff contact the child’s caregiver to re-assess symptoms using the web-based application. If the child continues to have symptoms that are not well controlled, the ACC recommends a guideline-based step-up in therapy using the steps described above.

Details of the Program Components

SB-PACT Web-Based Application

We developed web-based assessment and reporting tools for this program in order to systematically and efficiently evaluate children’s asthma symptoms and to obtain electronic physician authorization for preventive medications. The SB-PACT web application was developed in collaboration with a local software developer, SophiTEC, in Rochester, NY. SB-PACT includes three main communication components: screening tools to assess severity or control, reporting tools to relay information and provide recommendations for guideline-based care, and authorization tools to allow providers to authorize medications with directly observed therapy at school.

Following the initial development of the program, we held focus groups and in-depth interviews with school health staff (n=13), local physicians and nurse practitioners (n=8), pharmacists (n=5), and caregivers of children with asthma (n=5), all of whom provided feedback on user-friendliness and completeness of the system, as well as how to best streamline communication. These groups provided key insights that were incorporated in the final version of the SB-PACT program. The most common feedback from school health staff related to the structure and content of the screening tool. They requested the option to input free text into the system to convey notes or observations at school. Physicians mostly discussed the medication authorization component, with suggestions regarding the appearance of the symptom report and the ease of use of the authorization tool. We worked with the software developer to design a simplified symptom report with highlighting of important fields, and we streamlined the process of authorizing therapy. Pharmacists were comfortable with the system of medication prescribing and delivery, and were able to provide input on information content they require in order for this to occur reliably as requested. All groups, including caregivers, were supportive of the efforts to put this program into practice in schools.

The symptom assessment tools primarily use radio buttons and function as structured, guideline-based evaluations of children’s asthma symptoms. An algorithm is built into the assessment that computes an NHLBI severity or control classification, based on caregiver report of daytime and nighttime symptoms, rescue medication use, and number of asthma exacerbations. We also include open text fields in the assessment tools where users can communicate observations and special instructions or comments. SB-PACT also includes email reminders to complete open assessments. Data are housed and maintained by SophiTEC (a local software development company), and protected by high level encryptions and firewalls.

School Health Staff Training

School health staff training sessions were held at the beginning of the school year. School nurses and health aides from participating RCSD schools were asked to attend a single training session where they were provided with a user manual that outlined program procedures and common functions of the SB-PACT web application. These sessions were led by the ACC and members of the study team. Users were asked to create a unique username and password and instructed on how to access the web application. Following creation of their accounts, they were guided through the system including the process of entering children with asthma symptoms into the asthma registry and completion of the assessment tools.

Identification of Children for Screening

The SB-PACT assessment tools are built into the web application for systematic screening across user groups. School nurses and health aides are given the opportunity to identify potentially eligible children by entering names and contact information into the registry and completing a screening tool. This ten-item survey is designed to capture a snapshot of a child’s asthma symptoms in the school setting and gathers information about asthma symptoms at school, rescue medication use at school, and absenteeism due to asthma.

Symptom Assessment

School health staff then contact caregivers to complete an assessment of the child’s asthma severity from the caregiver’s perspective. This assessment obtains information on current asthma medications, symptoms, secondhand smoke exposure, PCP contact information and insurance status. Level of asthma severity or control is automatically computed at the end of this questionnaire, using guideline based algorithms.

Asthma Report Generation

The ACC reviews the symptom assessments for children with persistent symptoms or poor control. For each child randomly assigned to the intervention group, the ACC devises a guideline-based treatment plan based on age, level of severity, and current medications and generates an asthma report that summarizes the child’s asthma severity, reported medications, secondhand smoke exposure as well as a recommendation for the name, strength, dose and schedule of a preventive medication. This recommendation for therapy is tailored to each child, based on age and symptom severity, according to NHLBI guidelines. When a child does not have a rescue medication at home or school, a rescue inhaler is also recommended. Similarly, spacers are recommended, if needed, and any other relevant information is included in open text fields. Complete asthma reports are then transmitted electronically to the child’s PCP for review and authorization.

Authorization of Therapy

Upon submission of an asthma report, the web application triggers a secure email response to the PCP containing a brief summary of the SB-PACT program, a link to his/her patient’s asthma report, the ACC’s recommendation for therapy, and instructions on how to authorize therapy. Providers review this information and follow the prompts within the authorization tool to authorize the recommended therapy, suggest an alternative therapy, or decline therapy at school. Additional open text fields are included within this tool to allow providers the ability to offer further treatment instructions. Upon completion of the authorization tool, an email is automatically generated and sent to the ACC indicating the PCP’s response.

Delivery of Medications

Once the PCP authorizes a medication to be given at school, the ACC contacts the caregiver to confirm the treatment plan and proceeds to send the prescription(s) to the caregiver’s preferred pharmacy, on the PCP’s behalf. The pharmacy delivers the medications and spacers to both the child’s home (for use on weekend days and days absent from school) and school (for DOT on school days). School health staff demonstrate proper inhaler technique with the student and initiate DOT of the medication for each day the child attends school.

Symptom Reassessments

Per guideline-based care recommendations, school health staff complete follow-up symptom assessments one month after initiating therapy and again 4–6 weeks later to re-assess asthma control. If the child continues to have poor control despite DOT of the preventive medication at school, the PCP receives an updated asthma report including a recommendation to step-up therapy (e.g., increase dose or change medication) as outlined in the NHLBI guidelines. The steps to authorize and initiate therapy are then repeated, as described above.

The Asthma Care Coordinator (ACC)

Although much of the SB-PACT system is automated, the Asthma Care Coordinator, a registered nurse trained in pediatric asthma care, oversees all aspects of the web application to ensure that children receive quality, guideline-based care. Further, the ACC helps to maintain communication between caregivers, physicians, and school health staff. The ACC is available to answer questions from school health staff and to help conduct the symptom assessments with families, if necessary. In addition, the ACC maintains contact with PCPs about authorizations and coordinates medication deliveries with pharmacies. Lastly, the ACC reviews the asthma registry in the web-based system daily to ensure timely completion of all aspects of the SB-PACT program.

Usual Care Group

Families of children in the usual care group are encouraged to promptly make an appointment with their PCP to discuss their child’s asthma symptoms. These families are responsible for filling prescriptions for preventive medications and administering them daily to their child. To assure prompt care and safety of children in both groups, any child experiencing an exacerbation at the time of a survey is referred immediately to the PCP.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PILOT STUDY

We enrolled 100 children from 19 preschools and elementary schools at the start of the 2010–2011 school year (participation rate: 61%). We were able to successfully screen all children using the web-based system and send reports to the PCPs for each child in the intervention group. Forty-four of the 49 children randomly assigned to the intervention group (90%) were authorized by their PCP to begin DOT at school. Among the providers for these children, 82% used the electronic communication system for authorization, and the remainder requested documents by facsimile. Medications were delivered by the pharmacies for the majority (65%) of these subjects, or were either delivered by the ACC or picked up by the caregiver. DOT was successfully initiated for all of these children, and more than 1/3 received a medication dose adjustment upon reassessment.

DISCUSSION

Summary and Lessons Learned

Our method of web-based communication for symptom screening and report generation was successful in the majority of cases, and with the support of the Asthma Care Coordinator, enhanced asthma care was provided. The majority of children received their preventive medications through school, and more than 1/3 received a medication dose adjustment. This program has the potential to substantially improve asthma care in urban schools.

This project is specifically designed to produce an ultimately sustainable system for enhanced asthma care for urban children. The key processes of symptom screening, delivery of medications to the schools, and tracking of administration during the school year was facilitated through web-based technology and pre-specified algorithms that could be applied broadly to other systems and communities. Most city schools in the Rochester area and around the nation have access to computers and Internet capabilities, and the proliferation of information technology in public schools is steadily increasing.8 Since schools already routinely provide daily medications for other conditions such as attention deficit disorder, the provision of daily preventive asthma medications could be a simple system change to improve adherence and reduce morbidity. We included the services of a district-wide Asthma Care Coordinator to support this system of care, similar to the services currently being provided by health care systems around the nation.9,10 For this program, the ACC was a registered nurse trained in pediatric asthma care. However, with training, schools and communities could utilize existing health staff to carry out this role in a similar capacity. The ultimate goal is to promote diffusion of an effective and efficient mechanism of care throughout schools and maximize the health of high-risk children in urban communities.

There are several challenges in our preliminary work to develop the SB-PACT program that warrant comment. First, there can be significant barriers in implementing a new screening process in fiscally challenged and stressed school environments. Prior to SB-PACT, a long-term collaborative partnership with key school system stakeholders had been developed through work on earlier asthma initiatives. The credibility and trust gained through this relationship contributed to the school district’s willingness to consider SB-PACT as a practical step towards enhancing asthma care. While some school health staff members actively enrolled children into the program, others were unable to do so because of constraints on their time. Thus the ACC assumed more of this role than originally planned, which translates into increased program costs. While schools typically have personnel available to administer medications at some point in the day, they may be reluctant to do so in the context of tight budgets and limited staff support. Further, while provider engagement was enhanced by web-based communications and guideline based treatment recommendations, delays in provider authorizations occurred. A few providers did not routinely use e-mail communication and some were uncomfortable with any form of electronic communication. This makes the efficiency of communications difficult.

Pharmacy delivery was effective in many cases, but was constrained by each pharmacy’s limited delivery hours/days and by the requirement that families be home at the time of delivery to receive medications. Lastly, while medications were obtained primarily through the child’s health insurance, in some rare instances families were unable to obtain insurance or lost their medical insurance coverage. In these cases, the ACC offered assistance with obtaining health insurance coverage, but again this represents added costs to the system.

Lessons learned include the need to engage and support school health staff in the implementation of new processes, providing additional resources when possible but keeping cost and future sustainability in mind. In addition, flexibility is required when working with providers, since we found that providers’ willingness to use electronic communication varies. Electronic medical records may offer an additional avenue for efficient communications within existing systems. In fact, other programs have tested electronic asthma screening and prompting in primary care to improve the efficiency of guideline-based care delivery.11–14 Lastly, novel methods for healthcare assessment and delivery, such as telemedicine,15–17 might represent a method to enhance both efficiency and sustainability of chronic illness care within schools.

Conclusions

We have successfully developed the SB-PACT system and established its feasibility in providing preventive asthma care to high-risk children in the city school district, however several challenges remain. Clearly, careful planning is needed in considering each step in the process of securing delivery of enhanced preventive care. Our future research will focus on further refining this system of care, integrating each component into the schools and communities in which the children are served, and evaluating outcomes and costs. With additional modifications to refine the system further, this program has the potential to be implemented nationally in schools to improve adherence to preventive asthma care guidelines and enhance care among children with asthma.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andrew MacGowan, Donna Hill, PhD, Flora McEntee, RN, the school-nurse program and the Rochester City School District for their ongoing partnership and support of our work. We would also like to acknowledge SophiTEC for the development of the web-based technology used in this study. Lastly, we would like to thank Elise Wiesenthal for her assistance in preparing this manuscript and the SB-PACT study team for their limitless energy to help children with asthma.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

This work was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (RC1HL099432).

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Garbe PL, Sondik EJ. Status of Childhood Asthma in the United States, 1980 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S131–S145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report III: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. publication No. 07–4051. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halterman JS, Aligne CA, Auinger P, McBride JT, Szilagyi PG. Inadequate therapy for asthma among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2000 Jan;105(1 Pt 3):272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halterman JS, Auinger P, Conn KM, Lynch K, Yoos HL, Szilagyi PG. Inadequate therapy and poor symptom control among children with asthma: findings from a multistate sample. Ambul Pediatr. 2007 Mar-Apr;7(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halterman JS, Borrelli B, Fisher S, Szilagyi P, Yoos L. Improving care for urban children with asthma: design and methods of the School-Based Asthma Therapy (SBAT) trial. J Asthma. 2008 May;45(4):279–286. doi: 10.1080/02770900701854908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halterman J, Szilagyi P, Fisher S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to improve care for urban children with asthma: results of the School-Based Asthma Therapy trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:262–268. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halterman JS, McConnochie KM, Conn KM, et al. A potential pitfall in provider assessments of the quality of asthma control. Ambul Pediatr. 2003 Mar-Apr;3(2):102–105. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0102:appipa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray L, Thomas N, Lewis L U.S. Department of Education NCfES. Educational Technology in US Public Schools: Fall 2008. Washington D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloutier MM, Wakefield DB. Translation of a Pediatric Asthma-Management Program Into a Community in Connecticut. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):11–18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lob S, Holloman Boer J, Porter PG, Núñez D, Fox P. Promoting Best-Care Practices in Childhood Asthma: Quality Improvement in Community Health Centers. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):20–28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell LM, Grundmeier R, Localio R, et al. Electronic Health Record-Based Decision Support to Improve Asthma Care: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e770–e777. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiffman RN, Freudigman M, Brandt CA, Liaw Y, Navedo DD. A Guideline Implementation System Using Handheld Computers for Office Management of Asthma: Effects on Adherence and Patient Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;105:767–773. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCowan C, Neville RG, Ricketts IW, Warner FC, Hoskins G, Thomas GE. Lessons From a Randomized Controlled Trial Designed to Evaluate Computer Decision Support Software to Improve the Management of Asthma. Med Inform Internet Med. 2001;26:191–201. doi: 10.1080/14639230110067890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shegog R, Bartholowmew LK, Sockrider MM, et al. Computer-Based Decision Support for Pediatric Asthma Management: Description and Feasibility of the Stop Asthma Clinical System. Health Informatics Journal. 2006;12:259–273. doi: 10.1177/1460458206069761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller E. Solving the disjuncture between research and practice: telehealth trends in the 21st century. Health Policy. 2007;82:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McConnochie K. Potential of telemedicine in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics in Review. 2006;27(9):e58–e65. doi: 10.1542/pir.27-9-e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean S, Chandler D, Nurmatov U, et al. Telehealthcare for asthma: a cochrane review. CMAJ. 2011;183(11):E733–E742. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]