Background: Genes evolved in mammals for specialization of hearing.

Results: CEA cell adhesion molecule 16 (CEACAM16) is a structural component of the tectorial membrane and necessary for hearing at low and high frequencies.

Conclusion: CEACAM16 has evolved in mammals to broaden the auditory frequency range.

Significance: Mutation of CEACAM16 is responsible for human autosomal dominant hearing loss (DFNA4).

Keywords: Animal Models, Development, Electrophysiology, Hearing, Inner Ear, Carcinoembryonic Antigen, Cochlea, Deafness, Knock-out, Tectorial Membrane

Abstract

The vertebrate-restricted carcinoembryonic antigen gene family evolves extremely rapidly. Among their widely expressed members, the mammal-specific, secreted CEACAM16 is exceptionally well conserved and specifically expressed in the inner ear. To elucidate a potential auditory function, we inactivated murine Ceacam16 by homologous recombination. In young Ceacam16−/− mice the hearing threshold for frequencies below 10 kHz and above 22 kHz was raised. This hearing impairment progressed with age. A similar phenotype is observed in hearing-impaired members of Family 1070 with non-syndromic autosomal dominant hearing loss (DFNA4) who carry a missense mutation in CEACAM16. CEACAM16 was found in interdental and Deiters cells and was deposited in the tectorial membrane of the cochlea between postnatal days 12 and 15, when hearing starts in mice. In cochlear sections of Ceacam16−/− mice tectorial membranes were significantly more often stretched out as compared with wild-type mice where they were mostly contracted and detached from the outer hair cells. Homotypic cell sorting observed after ectopic cell surface expression of the carboxyl-terminal immunoglobulin variable-like N2 domain of CEACAM16 indicated that CEACAM16 can interact in trans. Furthermore, Western blot analyses of CEACAM16 under reducing and non-reducing conditions demonstrated oligomerization via unpaired cysteines. Taken together, CEACAM16 can probably form higher order structures with other tectorial membrane proteins such as α-tectorin and β-tectorin and influences the physical properties of the tectorial membrane. Evolution of CEACAM16 might have been an important step for the specialization of the mammalian cochlea, allowing hearing over an extended frequency range.

Introduction

The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)4 family, a subgroup of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is extremely variable in size and, with few exceptions, exhibits little sequence conservation between species. Phylogenetic analyses provide evidence that the primordial CEA gene family in mammals consisted of five genes, including the immune inhibitory receptor-encoding CEA-related cell-cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) ancestor. Most of the heterogeneity of CEA families between different species is derived from members that are closely related to CEACAM1. CEACAM1-related genes can be traced back to the last common ancestor of fishes and mammals (1). CEACAM1 exhibits a wide spectrum of functions including regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses, granulopoiesis, angiogenesis, glucose and fat metabolism, tissue architecture, and homoeostasis (2–10). Most significantly, from an evolutionary point of view, CEACAM1 in humans, mouse, and probably other species is exploited by bacterial and viral pathogens as a receptor to enter the host via mucosal surfaces through interaction with adhesins (11). Once inside the host, the pathogens can gain additional benefit by down-regulation of anti-pathogen immune responses through engagement of CEACAM1 on epithelial and immune cells (8, 10, 11). This dual level assault has led to the development of very similar decoy receptors during evolution as a countermeasure by the host (1, 12, 13). Taken together, the struggle to escape from pathogen recognition and generation of decoy receptors are probably responsible for the pronounced diversity and low sequence conservation observed between CEA families of different species (1).

The non-CEACAM1-like primordial members represent a more distantly related group of the CEA family-related genes of unknown function (CEACAM16, CEACAM18, CEACAM19, CEACAM20) (14). In contrast to CEACAM1-related genes, for which by sequence comparison alone no orthologous genes can be assigned, orthologs for this CEACAM subgroup were identified in placental mammals, marsupials, and in the monotreme platypus (1). In platypus, only CEACAM16 was found. Whereas CEACAM1-related members abound in amphibians and fishes, the group of orthologous CEACAMs appears to be restricted to the mammalian lineage (1).5 Among them, CEACAM16 sticks out in being exceptionally well conserved and representing the only secreted member with two immunoglobulin (Ig) variable (IgV)-like or N domains, one NH2-terminal (N1), and one COOH-terminal (N2) separated by two Ig constant (IgC)-like domains (A and B). With the exception of the secreted CEACAM1-related pregnancy-specific glycoproteins, which are found only in certain mammals (1), the vast majority of CEACAMs is membrane-bound and in general composed of one N domain followed by a varying number of IgC-like domains. CEACAM N domains are involved in homo- and heterotypic interactions whereby the β-sheet formed by β-strands C′′C′CFG is instrumental for the interaction with their ligands (15, 16). Therefore, the domain arrangement of CEACAM16 suggests interaction with two binding partners. Furthermore, CEACAM16 exhibits a very restricted expression pattern. Murine Ceacam16 was found to be weakly expressed in only 1 of 37 adult and embryonic tissues analyzed, i.e. in the cerebellum (14).

As a basis for functional analyses of this mammal-specific, highly conserved member of the CEA family, we searched expressed sequence tag (EST) databases for CEACAM16 clones. CEACAM16 ESTs were frequently detected in inner ear cDNA libraries. Immunohistochemistry of Ceacam16−/− and wild-type mice cochleae revealed specific expression in the tectorial membrane (TM), thus adding a fifth member to the list of non-collagenous proteins (α-tectorin, β-tectorin, otogelin, otolin) specific to this acellular extracellular matrix. The TM covers the sensory hair cells of the inner ear and translates sound-induced vibrations to shearing of hair cell stereocilia. Accordingly, the TM is an indispensable component of the mechano-electrical transduction that leads to amplification of sound-induced vibrations of the basilar membrane. Loss of CEACAM16 resulted in an increased hearing threshold mainly for frequencies below 10 kHz and impaired amplification above threshold possibly caused by disruption of the striated sheet of the TM with a concomitant change of its elasticity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Antibodies

HeLa, BOSC23, and HEK293T were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS Gold; PAA Laboratories GmbH) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2. The following antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit anti-α-tectorin antibody (sc-98277; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,), monoclonal mouse anti-c-myc antibody (MCA2200; Serotech), mouse anti-β-actin antibody (clone AC-74; Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-prestin/SLC26A5 antibody, rabbit anti-KIR4.1/KCNJ10 antibody, horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) (Southern Biotech), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled goat F(ab′)2 anti-mouse IgG/IgM from Jackson ImmunoResearch (Dianova). Polyclonal and monoclonal murine anti-murine and anti-human CEACAM16 antibodies were generated by genetic immunization and tested essentially as described before (17). The monoclonal anti-CEACAM16 antibody 9D5 was purified by protein G-Sepharose affinity chromatography and biotinylated using standard procedures.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription PCR

Human inner ear RNA was isolated from autopsy samples. The use of human autopsy samples of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Munich. The temporal bone was collected within 12 h after the subject's death and placed on ice. The oval and the round windows were opened, and the cochlea was perfused with RNAlater® (Ambion, Applied Biosystems). The inner ear was microdissected, and RNA was isolated using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen). From fresh murine tissue or tissue stored in RNAlater at 4 °C, RNA was isolated with the RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit including a DNA removal step (Qiagen). Tissues were homogenized in RLT buffer (Qiagen) using an Ultraturrax homogenizer (IKA Werke). Mouse cochleae were directly suspended in RLT by crushing the tissue with tweezers. The quality of RNA was analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system using the RNA 6000 Pico kit (Agilent Technologies). 1 μg of total murine or human RNA (Chemicon, Millipore GmbH; BioChain Institute) was reverse-transcribed using the Reverse Transcription System® (Promega) followed by PCR (25 μl total volume) with of the reverse transcription (RT) reaction and gene-specific primers (supplemental Table 1) using standard conditions. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the LightCycler technology (Roche Diagnostics) and gene-specific primers (supplemental Table 1). Crossing points (Cp) were used to calculate relative mRNA levels present in the RNA samples after β-actin mRNA normalization.

Gene Targeting in Embryonal Stem Cells and Generation of CEACAM16 Null Mice

All experiments that involved animals were based on the institutional guidelines of the Universities of Tübingen and Munich and registered and performed in compliance with the German Animal Protection Law (Regierung von Oberbayern and the Regierungspräsidium Tübingen). The targeting vector was constructed by insertion of Ceacam16 genomic regions comprising exon 1 (5′-region) and part of exons 5 and 6 (3′-region) into the pPTN4 vector (18). Ceacam16 regions were amplified by PCR (primers see supplemental Table 1) with BALB/c genomic DNA as template using the Expand High FidelityPLUS PCR System kit (Roche Diagnostics). The resulting targeting construct lacks a 6.8-kb region that comprises exons 2–4 and part of exon 5 of Ceacam16 that was replaced by a 1.7-kb neo cassette. Electroporation of the SalI-linearized targeting vector into the BALB/c-derived ES cell line BALB/c-I (19), G418 selection for recombinants, and embryonic stem (ES) cell propagation were performed as described before (20). Appropriate clones were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts, and these were implanted into a NMRI foster mother. The resulting male chimeras were backcrossed to BALB/c females to identify germ line transmission of the targeted allele and to produce mice heterozygous for the null mutation. F1 intercrosses of heterozygous mice finally resulted in F2 offspring on pure BALB/c background. Ceacam16−/− and Ceacam16+/+ strains were established and maintained at the animal facilities of Gene Center and the Walter Brendel Center of Experimental Medicine, University of Munich, Germany.

ES Cell and Mouse Genotyping

Homologous recombination between the targeting vector and Ceacam16 in drug-resistant ES cell clones was analyzed by long range PCR using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche Diagnostics) and the EUCOMM Expand Long Template genotyping protocol. As a positive control, a vector was created with an extended 5′-targeting region. Southern blotting was performed using BamHI-digested genomic DNA and 32P-labeled hybridization probes applying standard techniques. The established Ceacam16 knock-out and wild-type strains were genotyped using standard PCR reaction conditions and the primers indicated in supplemental Table 1.

Hearing Measurements

Thirty adult male and female Ceacam16−/− and Ceacam16+/+ mice (6 weeks to 19 months old) were used for hearing tests. Measurements of auditory brainstem responses (ABR) and distortion products of the otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) were performed as described (21–23), while mice were under anesthesia using ketamine (75 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (5 mg/kg body weight). In short, ABR to free field click (100 μs), noise burst (1 ms), and pure tone (3 ms, 1 ms ramp) acoustic stimuli were recorded with subdermal silver wire electrodes at the ear (active), the vertex (reference), and the back (ground) of the animals. Signals were amplified (50,100-fold), band-pass filtered (200 Hz high-pass and 5 kHz low-pass), and averaged for 64–256 repetitions at each sound pressure level (SPL) presented (0–100 or 0–110 db in steps of 5 db). Hearing threshold was defined as the lowest SPL that produced a potential visually distinct from background noise. The cubic 2f1 − f2 DPOAE was measured for primary tone f1 and f2 frequency (Hz) f2 = 1.24f1 and primary tone sound pressure level (dB SPL) L2 = L1 − 10 dB. Emission signals were recorded during sound presentation of 260 ms and averaged 4 times for each sound pressure (L1 ranging from −10 to 65 dB SPL) and frequency (f2 ranging from 4.0 to 32.0 kHz) presented. Threshold was determined as the L1 sound pressure that could evoke a 2f1 − f2 DP signal reliably exceeding 5–10 dB above noise level, with the noise level typically being at −20 dB SPL.

Acoustic trauma was induced with a loud sound of binaural exposure to 120-db SPL band-pass noise (4–16 kHz) in free field. ABR waves from individual ears were measured and analyzed for −10 to +85-db SPL stimulation level to click stimuli. From averaged ABR waves, the signal derivative was calculated as a measure for the waviness of the curves and presented as input-output (I/O) function. An ABR wave with large positive and negative deflections, i.e. a strong ABR signal, would reflect in a higher signal derivative. A flat curve will have a signal derivative of ∼0.

Immunohistology

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by cervical dislocation. The cochlea and vestibular organ were quickly removed en bloc and fixed for 30–45 min in 4% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-buffered formaldehyde at room temperature, rinsed in PBS, decalcified for 24 h in 0.18 m citric acid, 0.44 m EDTA pH 7.1, at 4 °C, and stored in 70% ethanol at 4 °C until embedded in paraffin wax using a Shandon Hypercenter XP Enclosed Tissue Processor (Thermo Scientific). 3–5-μm thin sections were applied to SuperFrost Ultra Plus® slides (Menzel), heated to 40 °C for 0.5 h, dried at room temperature for 2 days, deparaffinized, and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was achieved by heating to ∼95 °C of the tissue sections in Target Retrieval Solution, pH 9 (DakoCytomation), for 30 min followed by cooling to room temperature for 20 min. After blockage of endogenous peroxidase and biotin by incubation with 3% H2O2, 10% methanol in PBS for 5 min at room temperature and by using the streptavidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories; Linearis), respectively, sections were reacted with the biotinylated anti-CEACAM16 antibody 9D5 (4 μg/ml) for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C followed by a 1-h incubation with horseradish peroxidase-coupled streptavidin (Sigma) and stained by incubation with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole.

For immunofluorescence staining, the cochlea and the vestibular organ were fixed for 2 h in 2% freshly prepared formaldehyde, 125 mm sucrose in 100 mm PBS, pH 7.4, at room temperature followed by overnight incubation with 25% sucrose with 1 mm protease inhibitor Pefabloc SC (Roche Diagnostics) in PBS. Decalcification of cochleae from adult mice was performed using Rapid Bone Decalcifier medium (Eurobio, Fisher) for 15 min to 2 h. Cochleae were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Miles Laboratories). 10-μm cryosections were mounted on SuperFrost Ultra Plus® slides, dried for 1 h, and stored at −20 °C. Cochlear sections were first treated with 0.5% Triton-X-100 (Sigma) for 10 min and blocked with 7% normal goat serum (Sigma) in PBS for 1 h followed by overnight incubation with anti-CEACAM16 antibody 9D5 (4 μg/ml) and rabbit polyclonal anti-prestin or rabbit anti-KIR4.1 antibodies at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were detected with either Cy3-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit Ig antibody (0.35 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or Alexa-488 conjugated goat-anti-mouse Ig antibody (1:1500; Molecular Probes). Sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and photographed using the Olympus BX61 microscope with epifluorescence and the cellSens Dimension® Software (Olympus). For all immunohistochemical pictures image stacks along the x axis (z-stack) and deconvolution were used.

In Situ Hybridization

Cryosections were prepared as described for immunofluorescence staining. Digoxigenin-tagged sense and antisense riboprobes were transcribed from the pCMV-SPORT6 vector containing the 5′-half of the murine CEACAM16 cDNA. Sections were hybridized with 1:50 diluted riboprobes in 1× hybridization buffer (Roche Diagnostics) at 64 °C overnight, washed twice in 0.1% saline-sodium citrate buffer, and blocked with 1× Blocking Reagent (Roche Diagnostics) in 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.3% Triton X-100 (blocking solution). Riboprobes were reacted with alkaline phosphatase-coupled anti-digoxigenin antibodies (Roche Diagnostics) diluted 1:750 in blocking solution for 30 min at 37 °C followed by staining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (Sigma) for 5–20 h. Sections were embedded in Mowiol (Roth), and pictures were taken using a Olympus AX70 microscope.

Generation of CEACAM16 Expression Vectors

Full-length murine and human CEACAM16 were amplified from total cochlear RNA and stria vascularis RNA, respectively, after reverse transcription (see above) using primers located in the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (supplemental Table 1) and High Fidelity PCR Enzyme Mix (Fermentas) and cloned into the vector pCMV-SPORT6 (sequences were deposited at GenBankTM with accession numbers NM_001039213 and NM_001033419). For identification of the domains responsible for homophilic interaction of CEACAM16, intermolecular disulfide bridge formation, and binding with monoclonal antibody, deletion constructs were generated in the VV1, pB1 (Aldevron Freiburg), and pAPtag-5 vectors (GeneHunter Corporation, Nashville, TN), which allow the expression of recombinant proteins with NH2-terminal or COOH-terminal myc tags. VV1 and pB1 also provide a COOH-terminal signal sequence for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchorage. The addition of a stop codon in front of the GPI signal yielded secreted proteins.

Cell Adhesion Assay

HEK293T cells (2 × 105 cells/6-well plate well) were transiently transfected with 2 μg of VV1, pB1, or pAPtag-5 expression plasmids and 3 μl of FuGENE 6 in 1 ml of media. After 48 h cells were harvested by pipetting, washed in PBS, and resuspended by repeated pipetting in 2.5 ml of PBS at room temperature to form a single cell suspension (0.625 × 106 cells/2.5 ml). To some samples with high transfection efficiency half of the cells were replaced with non-transfected HEK293T cells to adjust the fraction of CEACAM16-expressing cells to ∼50% to visualize homotypic cell aggregation. The cell suspensions were slowly rotated or repeatedly gently mixed to prevent sedimentation of the cells for 30–60 min. 100 μl of the cell suspension were pelleted onto glass slides (SuperFrost Plus®) using a cytocentrifuge (Shandon). The slides were dried for 12–18 h at room temperature and stored at −20 °C. After fixation in acetone and blockage of endogenous peroxidase as described above, cells were incubated with 2 μg/ml mouse anti-human CEACAM16 9D5 or 10 μg/ml mouse anti-c-myc antibody. Bound antibodies were visualized using the ImmPRESS anti-mouse Ig kit (Vector Laboratories). The size of aggregates consisting of CEACAM16-expressing cells was determined using a microscope fitted with a graded ocular. Expression levels of CEACAM16 domains on HEK293T cells were quantified after incubation with anti-c-myc antibody (100 μg/ml) followed by FITC-coupled goat anti-mouse Ig antibody (75 μg/ml) using FACScan analysis (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences).

Structure Prediction

The three-dimensional structures of CEACAM16 was modeled using the Geno3D-release 2 homology modeling software (15, 24). For modeling of the entire CEACAM16 molecule we selected human CEA (PDB code 1E07) as a template. Individual Ig domains were modeled by selecting the following templates: pdb2qsqA-0 and pdb1l6zA-0 for CEACAM16 N1 and CEACAM16 N2, pdb1l6zA-0 for CEACAM16 A, pdb1cs6A-2, and pdb2om5A-0 for CEACAM16 B.

Western Blot Analysis

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs encoding GPI-linked or secreted CEACAM16 domains as described above. 1 × 106 cells were dissolved in 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, pH 8, protease inhibitor mixture (Complete Mini; Roche Diagnostics)) on ice, sonicated briefly, vortexed, centrifuged at 20,800 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and stored at −20 °C. The cell culture supernatant (with 5% FBS) of cells transfected with expression constructs for secreted CEACAM16 variants was centrifuged as above and stored at −20 °C. After the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (without 2-mercaptoethanol), samples were heated in the presence or absence of 60 mm dithiothreitol for 10 min at 95 °C and stored at −20 °C until Western blot analyses were performed. Samples (corresponding to 5 μl of lysate) were separated by electrophoresis on 8 or 12% polyacrylamide gels containing SDS and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked overnight in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (Roth) (PBS-T) containing 5% blotting-grade milk powder (Roth). Antigen detection was performed using anti-CEACAM16 (5 μg/ml), anti-c-myc (1.6 μg/ml), or anti-β-actin antibodies (2.5 μg/ml) in PBS-T with 5% milk powder. Subsequently, membranes were washed with PBS-T and incubated with secondary peroxidase-coupled antibodies (Calbiochem) diluted 1:4000 in PBS-T with 5% milk powder. Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence using ECL Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare).

Statistics

Data are presented as the S.D. or S.E. Differences of the mean were compared for statistical significance by 2-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism 2.01) and Student's t test. Statistical significance was tested at α = 0.05. The two-sided Fisher's exact test was used for contingency testing.

RESULTS

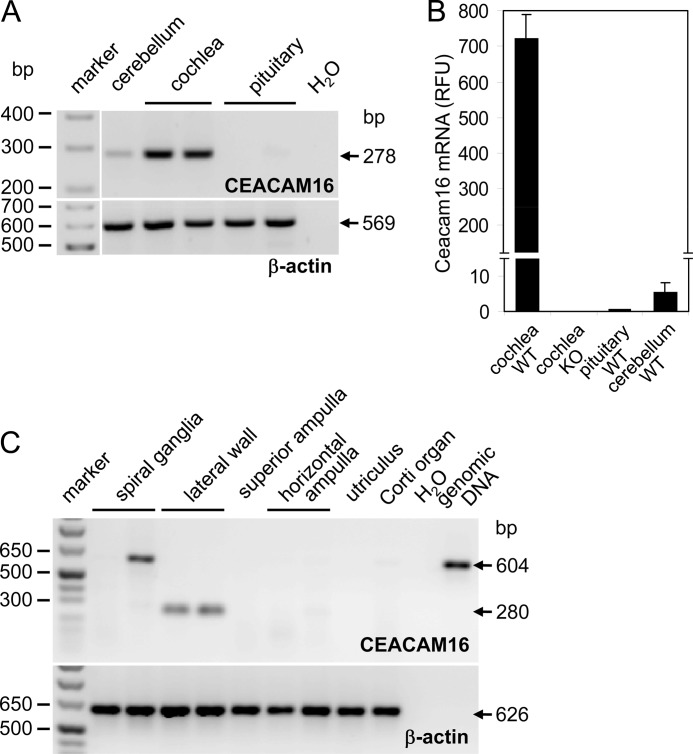

CEACAM16 Is Selectively Expressed in Inner Ear

A survey of expressed sequence tag (EST) databases revealed that 80% of a total of 57 Ceacam16 cDNAs originated from adult inner ear or organ of Corti (supplemental Fig. 1A), which suggested preferential expression of CEACAM16 in inner ear tissue. This was corroborated by the analysis of CEACAM16 transcripts by PCR amplification using gene-specific primers after reverse transcription of a panel of 22 human tissues, including brain and pituitary, which in mice were found to contain low levels of Ceacam16 mRNA (see below). CEACAM16 mRNA was detected in none of the tissues (supplemental Fig. 1B). However, a strong signal was found for total RNA from murine cochleae (Fig. 1A). The presence of more than 100-fold lower levels of Ceacam16 transcripts could also be demonstrated in cerebellum and pituitary (Fig. 1, A and B). In dissected adult human inner ears (Fig. 1C), CEACAM16 transcripts could be detected in lateral wall preparations but not in other parts of the cochlea (organ of Corti, spiral ganglia) or in the vestibular organ (ampulla of the semicircular canal and horizontal ampulla, utricle).

FIGURE 1.

CEACAM16 mRNA is selectively expressed in the cochlea. CEACAM16 transcripts were identified by end point (A and C) and real-time RT-PCR (B). CEACAM16 mRNA was found in murine cochleae as well as at lower levels in murine cerebellar and pituitary tissue (n = 2; A and B) and in the lateral wall of dissected human inner ears (C). β-Actin cDNA was amplified to control intactness of the RNAs (A and C) and for normalization (B). RFU, relative fluorescence units. The 604-bp DNA fragment in one of the spiral ganglia cDNA samples corresponds to a product with retained intron and thus is probably derived from contaminating genomic DNA (C). The expected sizes of the PCR products are indicated by arrows.

Young Ceacam16−/− Mice Have Increased Hearing Threshold for Pure Tones and Limited Outer Hair Cell Amplification Force

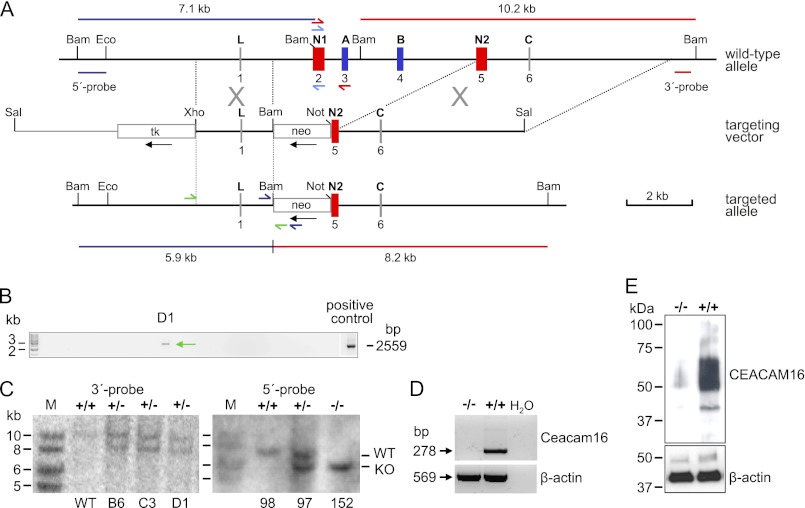

The restricted expression of the Ceacam16 gene in the cochlea prompted us to asses whether inactivation of Ceacam16 would impair hearing in mice. To this end we deleted exons 2, 3, 4, and part of exon 5 including its splice acceptor site in BALB/c ES cells by homologous recombination, which should lead to a Ceacam16 null allele (Fig. 2A). To identify clones with putative homologous recombination events, we used long range PCR and primers in the neo gene and in the 5′-upstream region distal to the genomic fragment present in the targeting vector. 3 of 200 G418-resistant ES cell clones yielded a fragment with the expected size (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Southern blot analysis using a unique probe downstream of the 3′-targeting region revealed the presence of the expected 8.2 kb genomic fragment after BamHI digestion, suggesting correct homologous recombination events in all three ES cell clones (Fig. 2C, left panel). Clone C3 was injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate chimeric mice that were back-crossed to BALB/c mice. Albino mice, which carried the null allele, were mated to obtain Ceacam16−/−, Ceacam16+/−, and Ceacam16+/+ mice. The frequencies of the resulting genotypes were close to the expected Mendelian ratio (25.3:42.1:32.6; n = 95). No sex bias was observed (Ceacam16−/− male/Ceacam16−/− female = 13:12). Southern blot analysis using a probe from the 5′-upstream region (Fig. 2A) confirmed correct homologous recombination in mice derived from ES cell clone C3 (Fig. 2C, right panel). Ceacam16−/− mice are fertile, and the mean litter size (±S.D.) is lower than that of wild-type matings, but the difference does not reach significance (4.1 ± 1.6, n = 11; 5.7 ± 1.9, n = 9; p = 0.086, Mann-Whitney U test). No corresponding mRNA and protein could be detected in cochleae of Ceacam16−/− mice (Fig. 2, D and E).

FIGURE 2.

Targeted disruption of the murine Ceacam16 gene. A, shown is targeting strategy. Structure of the wild-type allele (top), targeting construct (middle), and recombinant allele (bottom) is shown. The 6 exons of Ceacam16 are shown as boxes with the encoded domains indicated above (exons encoding IgV-like domains are red; IgC-like domains are blue). Except for BamHI, only restriction endonuclease sites relevant for cloning or probe generation are shown. Neo and tk expression cassettes, which can be used for the selection of homologous recombinants (G418- and ganciclovir-resistant) are shown as open boxes. Black arrows indicate the transcriptional direction. The vector sequence within the targeting plasmid is shown as a thin line. The positions and predicted sizes of the DNA fragments obtained after digestion with BamHI and hybridization with the 5′- (blue) and 3′-probes (red), respectively, are indicated. Positions of primers used for identification of ES cell clones with homologous recombination, genotyping, and detection of Ceacam16 transcripts are shown by half arrows. B, identification of targeted ES cell clones by long range PCR is shown. A total of three recombinant ES cell clones could be identified of 200 clones tested. C, Southern blot analysis is shown. Analysis of DNA from ES cell clones B6, C3, and D1 and from F2 offspring (#97, #98, #152) of a C3-derived chimeric founder after heterozygous mating of F1 mice demonstrated correct recombination events at 3′-region and the 5′-region of the targeted allele of Ceacam16, respectively. The absence and presence of CEACAM16 mRNA and protein was demonstrated in adult (>20 weeks old) Ceacam16−/− and Ceacam16+/+ mice by RT-PCR (D) and Western blotting (E), respectively. As a control, β-actin-specific primers and antibodies were used. The mobility and size of marker DNA fragments and proteins are shown in the left margins. Wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous genotypes (−/−) for the Ceacam16 knock-out allele are indicated above the lanes.

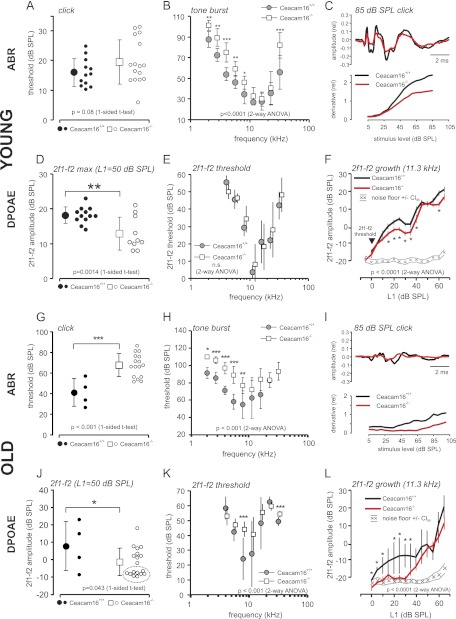

To assess the loss of CEACAM16 on the hearing function, we studied young Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice (1–2 months old) by recording ABR and distortion products of the otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE). ABR hearing threshold with click stimuli were not found to be significantly different (Fig. 3A), indicating that wild-type and Ceacam16−/− mice still had a similar “best hearing” at this young age. In the low and high frequencies of the hearing range thresholds were significantly increased in Ceacam16−/− mice (Fig. 3B), indicating impaired auditory signal transduction in the cochlea at frequencies toward the borders of the hearing range (2–8 and >22 kHz), where higher stimulation levels are needed to evoke an ABR response (>40-db SPL). This threshold loss was not seen by stimulation with the multifrequency click stimulus (Fig. 3A), which coincidentally excites multiple parts of the cochlea and is a measure for the best threshold response. However, single ears of Ceacam16−/− mice appear to have already increased threshold (Fig. 3A, open circles), but differences are not quite significant (p = 0.08). Nevertheless, ABR waveform analysis for suprathreshold stimulation could disclose reduced signal strength (Fig. 3C, upper panel, amplitude) and “waviness” (Fig. 3C, lower panel, derivative) in brainstem responses. To find out whether the origin of the hearing loss is based on a sensory-neural hearing loss by impaired inner hair cells (IHCs), synaptic transmission, or spiral ganglion neuron malfunction or rather a deficit in the active amplification process in the cochlea by outer hair cells (OHCs) motility, DPOAE functions were studied. DPOAE signals to a stimulus level of 50 db SPL (L1) is a measure for the optimum (max) amplification by OHCs. 1–2-month-old Ceacam16−/− mice had a significantly reduced 2f1 − f2 DPOAE amplitude at this stimulation level (Fig. 3D), indicating the reduction of the force coupled into the cochlear amplifier by OHC motility. On the other hand, threshold SPL for evoking DPOAE signals were not found to be significantly different (Fig. 3E, p = 0.163, 2-way analysis of variance). This was also reflected in the growth of the DPOAE signal with increasing stimulus level L1 (Fig. 3F, shown for 11.3 kHz); whereas the threshold for 2f1 − f2 signal in both Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice was not significantly different, growth of 2f1 − f2 dropped behind in Ceacam16−/− mice at suprathreshold stimulation levels, indicating reduced force coupling into the cochlear amplifier over the whole suprathreshold sound pressure range.

FIGURE 3.

Hearing function of Ceacam16−/− mice. Young (1–1.4 months old) (A–F) and old Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice (7–19 months old) (G–L) were analyzed for ABR threshold. Click (A and G) and pure tone stimulation (B and H) is shown. Hearing threshold was significantly increased in the low and high frequency hearing range in young Ceacam16−/− mice. In aged Ceacam16−/− mice threshold increase was detected at the lower frequency range of hearing (2–8 kHz). C and I, ABR waveform to click stimuli of 85-db SPL level along 10-ms recording time (upper panel) and waviness of ABR amplitude deflections (derivative, lower panel) as a function of stimulation level (db SPL) are shown. ABR waveform upon click stimulation showed the typical waves in young wild-type mice and similar waveform but reduced amplitudes in young Ceacam16−/− mice. ABR amplitude, latencies, and waviness are affected by age and are furthermore impaired in the Ceacam16−/− mice. In aged mice ABR amplitudes were smaller in wild-type mice and even further reduced in Ceacam16−/− mice. Signal derivative reveals a similar threshold but reduced ABR signal strength (gain) in the ABR wave of Ceacam16−/− mice at suprathreshold stimulation, resulting in a downshift of the curve. Signal derivative for aged Ceacam16−/− mice displays a loss of threshold and loss of suprathreshold gain. Amplitudes (D and J), threshold (E and K), and growth functions (F and L) of the 2f1 − f2 DPOAE were measured for young and old Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice. Growth function is shown for f2 = 11.3 kHz stimulation with increasing sound pressure (mean ± S.E.). In young mice, DPOAE threshold was not found to be different (E and arrowhead in F), but suprathreshold signal amplitudes fell behind the values for wild-type mice, indicating reduced coupling of force by OHC motility into the cochlear amplifier. DPOAE amplitudes were still significantly decreased for aged Ceacam16−/− mice as compared with wild-type mice, and many individuals had amplitudes dropped to nearly noise level (open circles clustered at ∼−10-db SPL 2f1 − f2 amplitude; J, circled). OHC amplification loss in aged Ceacam16−/− mice became evident from the 2f1 − f2 threshold audiogram (K) and from the DPOAE growth function (L). Black symbols in E and K are slightly horizontally displaced for better visualization. Statistical significance of differences were tested by t test (click, 2f1 − f2 max) or 2-way analysis of variance with post hoc t test (tone burst, 2f1 − f2 growth). Significance levels are given in the graph with p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001(***). Small symbols in A, D, G, and J show values for single ears. The numbers (n) of ears analyzed are indicated. Mean ± S.D. or ± S.E. (L, 2f1− f2 growth).

Aged Ceacam16−/− Mice Have Impaired Hearing for Click, Noise, and Pure Tone stimuli and Have Reduced Cochlear Amplification

Auditory function is subject to age-related changes (age-related hearing loss). To study the importance of the CEACAM16 protein for the maintenance of hearing function in advanced age, we measured ABR and DPOAE functions in Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice at the age of 7–19 months. The ABR threshold was examined with click, noise burst, and frequency-specific tone burst stimuli in 10 aged Ceacam16−/− mice (Fig. 3, G–L). The threshold was significantly increased in Ceacam16−/− mice for click (Fig. 3G), noise burst (not shown), and frequency-specific stimuli of 2–8-kHz stimulation frequency (Fig. 3H). From the ABR threshold, the loss of hearing function that has been found already in young mice exclusively by frequency-specific stimulation (compare Fig. 3B) now manifests also with click and noise burst stimulation because the threshold for best hearing frequencies was also affected.

ABR waveform amplitudes were reduced, and latencies were prolonged by age (Fig. 3I, upper panel) and ABR waveform deflections (waviness as a function of stimulus level (db SPL) was reduced by age-related hearing loss in wild-type and knock-out animals (compare Fig. 3, C and I, lower panel).

The DPOAE functions (Fig. 3, J–L) confirm an age-related reduction in 2f1 − f2 amplitude in both, wild-type, and knock-out mice (compare Fig. 1, D and J) and show the reduced cochlear amplification also in aged mice. The DPOAE threshold, not significantly different between young wild-type and knock-out mice (Fig. 3E), has become significantly affected in aged Ceacam16−/− mice as compared with wild-type mice, seen by the 2f1 − f2 growth function for 11.3-kHz stimulation (Fig. 3L) and the DPOAE threshold audiogram (Fig. 3K). In conclusion, the hearing deficits described in young Ceacam16−/− mice were found also in aged mice, with a higher degree of obviousness in the OHC amplification-based DPOAE threshold function.

Ceacam16−/− Mice Are Not More Vulnerable to Noise Exposure Than Age-matched Littermate Wild-type Mice

The relevance of CEACAM16 protein for the functional resistance against noise overexposure and for the maintenance of normal auditory function after noise-induced cochlea trauma was examined by exposing mice to the loud sound of 4–16-kHz band noise, 120-db SPL root mean square for 1 h. Hearing function was monitored by ABR and DPOAE measurements before and 6 days after noise exposure. Noise overexposure leads to permanent sensory trauma on the IHC level (loss of ABR threshold) and on the OHC level (loss of DPOAE threshold and amplitude). Ceacam16−/− mice had a similar or even smaller loss of auditory function as compared with Ceacam16+/+ mice (supplemental Fig. 2); loss of ABR threshold for click stimuli (supplemental Fig. 2A) was not significantly different from wild-type mice, and loss of threshold for frequency specific stimuli was similar in the high frequency range as compared with wild-type mice (supplemental Fig. 2B) and was even significantly smaller in the low frequency range. The smaller loss can be explained by the already increased threshold for frequency-specific stimuli in Ceacam16−/− mice. Supplemental Fig. 2, C and D show a similar profile for the damage on the OHC level; the loss of suprathreshold 2f1 − f2 signal strength was significantly smaller in Ceacam16−/− mice than in Ceacam16+/+ mice (supplemental Fig. 2D). The loss of the DPOAE threshold was smaller in Ceacam16−/− mice than in wild-type mice even though the initial 2f1 − f2 DPOAE threshold was similar between both genotypes before noise exposure (Fig. 3E). Taken together, the slightly hearing-impaired phenotype of Ceacam16−/− mice, which was mainly based on the reduced function of OHC amplification, led to reduced vulnerability of OHC function and less ABR threshold loss after noise exposure.

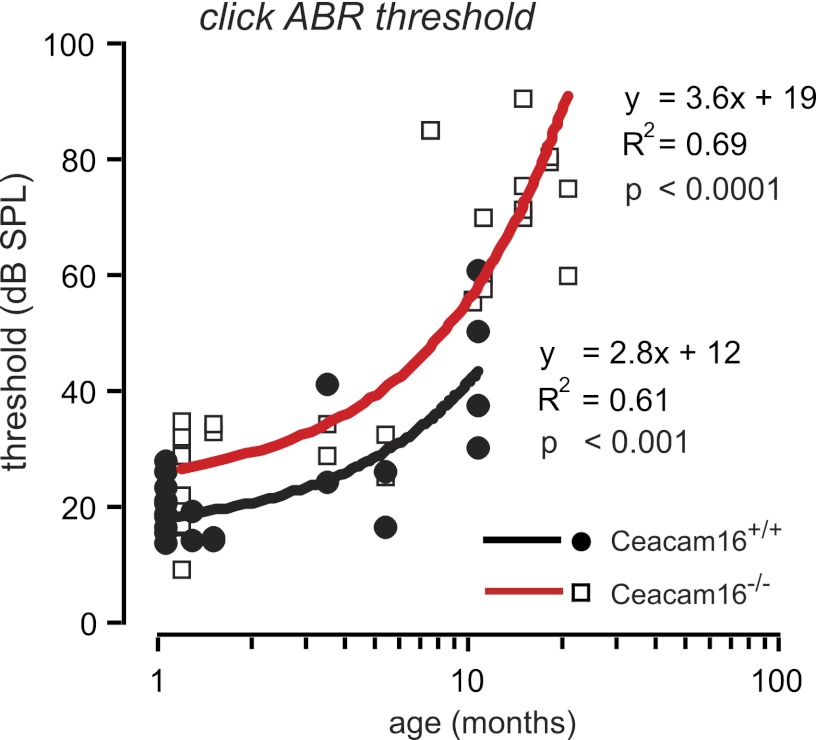

Age-related Progression of Hearing Threshold Loss Affects Ceacam16−/− and Ceacam16+/+ Mice in Similar Way

With increasing age, threshold for click ABR stimuli increased in both Ceacam16−/− and Ceacam16+/+ mice (Fig. 4) in parallel (Pearson correlation coefficient, p < 0.001) with a 10-db higher threshold in Ceacam16−/− mice.

FIGURE 4.

Progression of age-related hearing loss. ABR threshold to click stimuli was measured in aging Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice, 1–19 months of age. Individual ear threshold (db SPL) was correlated to age (months). Continuous lines show a linear fit. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (R2) and significance of correlation is given close to the line fit. For both Ceacam16+/+ and Ceacam16−/− mice, loss of ABR hearing threshold showed a similar progression with age. Nevertheless, the threshold for Ceacam16−/− mice was continuously significantly higher.

CEACAM16 Is Structural Component of TM in Organ of Corti and of Macula-associated Matrix of Vestibular Organ

The type of hearing deficit observed in Ceacam16−/− mice suggested an involvement of the TM, an acellular sheet of matrix that runs along the length of the cochlea. It is attached to the spiral limbus, spans the spiral sulcus, and covers the organ of Corti with its sensory hair cells. To be able to investigate the distribution of CEACAM16 in the inner ear, we generated a monoclonal anti-CEACAM16 antibody that binds to the IgC type A domain of both murine and human CEACAM16 (supplemental Fig. 3). Immunohistology with this biotinylated monoclonal antibody revealed strong staining of the whole TM from the base to the helicotrema of the cochlea of adult wild-type mice (Fig. 5A and data not shown). No other structure was consistently stained in the adult wild-type cochlea in comparison to the cochlea of Ceacam16−/− mice. In addition, the otolith-containing acellular gel overlying the macula of the saccule was also strongly stained (compare Fig. 5, C and G). The saccule registers information about linear movements in the vertical plane. Besides in the extracellular matrices of the cochlea and the saccule, CEACAM16 was found by immunohistology in interdental cells, Deiters cells, and possibly in OHCs (Fig. 5, I–K, and Fig. 6, G, I, J, and L). Double-staining using fluorescently labeled anti-CEACAM16 antibodies and antibodies specific for prestin/KCNJ10, an OHC marker, ruled out the presence of CEACAM16 in OHCs of adult P49 Ceacam16+/+ mice (Fig. 7, D–F). Using KIR4.1/SCL26A5-specific antibodies, which label Deiters cells and pillar cells but not OHCs, confirmed the presence of CEACAM16 in Deiters cells (Fig. 7, A–C). Interestingly, CEACAM16 seems to be present in vesicular structures in the body as well as in the projections of Deiters cells and appears to reach into the reticular lamina that covers the cells of the organ of Corti (Fig. 7, C and I). IHCs as well as pillar cells were stained at the apical end (Fig. 7, G and H). In cochlear sections of Ceacam16−/− mice, no staining with the CEACAM16 antibody was observed (Fig. 7A, inset). In situ hybridization of cochlea from young rats (P12) with a Ceacam16 antisense probe confirmed expression of Ceacam16 in Deiters cells, interdental cells of the limbus and to a lesser degree in phalangeal, inner pillar cells, and possibly in inner hair cells in a phylogenetically closely related species (Fig. 8, A–C). No other structures were stained in the inner ear including the utricle and the labyrinth (data not shown). We noticed that in adult wild-type mice the TM was often detached from the OHCs and more contracted in comparison to the TM in Ceacam16−/− mice (compare Fig. 5, B and F, for example). This difference between wild-type and CEACAM16−/− mice was statistically significant (p = 0.0003; Fisher's exact test; WT, number of cochleae n = 8; KO, n = 7; Fig. 5L). No gross abnormality of the distribution of α-tectorin, one of the major protein components of the TM, was seen in Ceacam16−/− mice (compare Fig. 5, D and H). Therefore, deposition of α-tectorin into the tectorial membrane is not perturbed by the absence of CEACAM16.

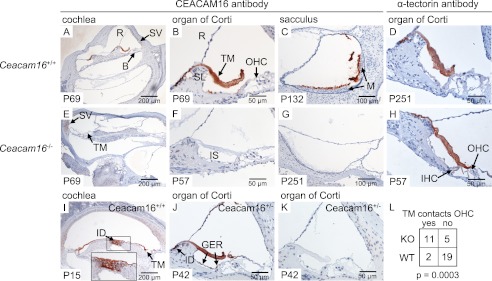

FIGURE 5.

Expression of CEACAM16 in the cochlea and vestibular organ. Expression of CEACAM16 was analyzed in the cochleae and vestibular organ of Ceacam16+/+ (A–C, I, and J) and Ceacam16−/− mice (E–G) by immunohistology using the biotinylated monoclonal anti-human CEACAM16 antibody 9D5, which cross-reacts with murine CEACAM16. CEACAM16 (brown stain) was observed in the acellular TM (A, B, I, and J) and in the extracellular matrix covering the macula cells of the saccule (C) in wild-type but not in Ceacam16−/− mice. Furthermore, staining for CEACAM16 was observed in interdental cells in the helicotrema region of P15 wild-type cochleae (I) and also in adult Ceacam16+/− mice (J). No staining was seen when only horseradish peroxidase-coupled streptavidin was added (K). Comparable staining for α-tectorin was found in the TM in both Ceacam16+/+ (D) and Ceacam16−/− mice (H). The age of the mice (days post partum) is indicated at the lower left corners. Note that the TM of Ceacam16−/− mice is significantly more often in contact with the OHCs (E, F, and H), whereas it is either detached or more retracted in wild-type mice (B, D, I, and J). No difference was observed when different regions of the cochlea (base, medal region, or helicotrema-proximal) were analyzed. Five wild-type and four Ceacam16−/− mice, representing eight and seven cochleae, respectively, were evaluated; p = 0.0003, Fisher's exact test (L). B, basilar membrane; GER, greater epithelial ridge; ID, interdental cells; IS, inner sulcus; M, macula; R, Reissner's membrane; SV, stria vascularis; SL, spiral limbus; TM, tectorial membrane.

FIGURE 6.

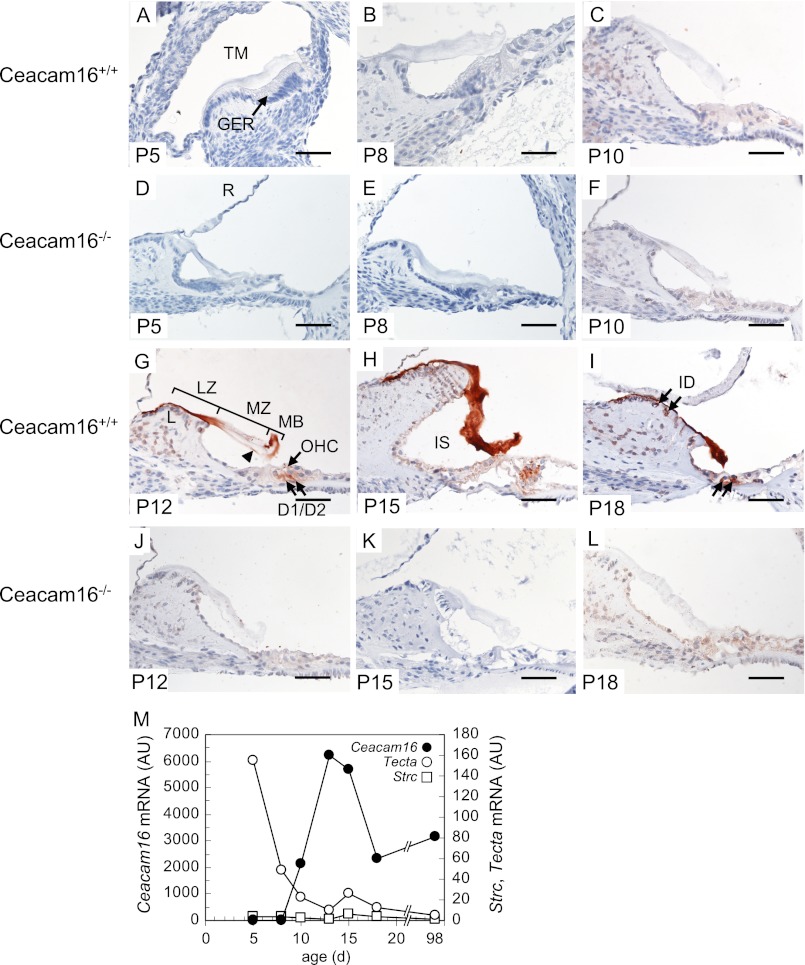

Postnatal expression of CEACAM16 in the organ of Corti. Expression of CEACAM16 was analyzed in the cochleae of Ceacam16+/+ mice 5–18 days post partum (P5-P18) by immunohistology using the monoclonal anti-human CEACAM16 antibody 9D5 (A–C and G–I). As the negative control, cochleae of Ceacam16−/− mice were analyzed (D-F and J–L). CEACAM16 (brown stain) was observed in the TM starting at P12 and continued to be present in P18 mice. Note the preferential staining at the marginal band (MB) and limbal zone (LZ) and the sulcus proximal part of the medial zone (MZ) of the TM (arrowhead) in P12 and the lack of staining in the middle part. In P15 and P18 mice homogenous staining for CEACAM16 was found (H and I). In P12, P15, and P18 cochleae, CEACAM16 was present also in OHCs, Deiters cells, and in interdental cells (G–I, arrows). Magnification bar, 50 μm. The appearance of immunoreactive CEACAM16 protein in cochlear tissues is preceded by Ceacam16 mRNA expression detectable from P10 onward with a maximum around P13, a time point where only marginal amounts of α-tectorin (Tecta) and stereocilin (Strc) mRNA are found by quantitative-PCR. Note the continued expression of Ceacam16 into adulthood that is not observed for Tecta and Strc (M). AU, absorbance units. GER, greater epithelial ridge; D1 and D2, Deiters cell 1 and 2; ID, interdental cells; IS, inner sulcus; L, limbus; LZ, limbal zone; MB, marginal band; MZ, medial zone; R, Reissner's membrane.

FIGURE 7.

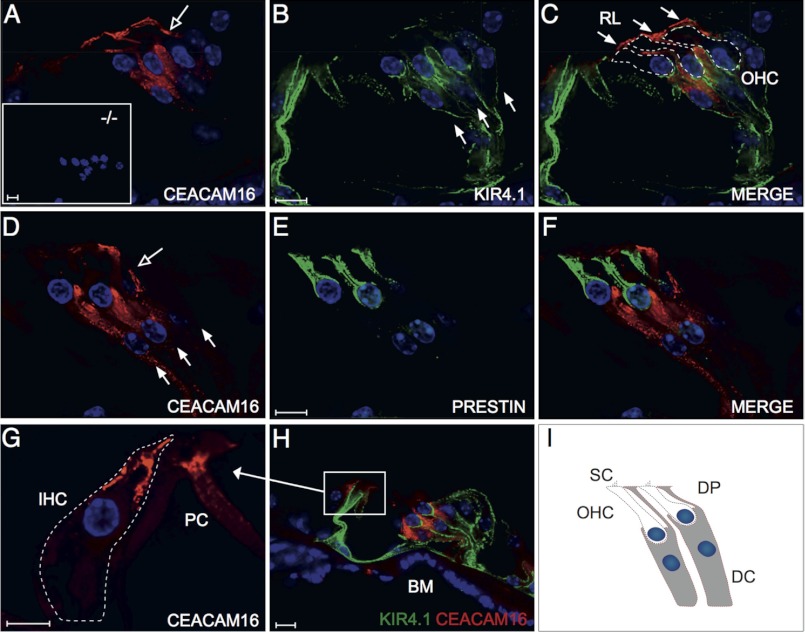

CEACAM16 is expressed in Deiters cells. Expression of CEACAM16 was analyzed in the organ of Corti of adult (P49) Ceacam16+/+ (A–F, G, and H) and 44-week-old Ceacam16−/− mice (A, inset) by immunofluorescence using the monoclonal anti-CEACAM16 antibody 9D5. CEACAM16 (red) was observed in the OHC-supporting Deiters cells (A, C, D, F, and H), which were identified by the potassium channel protein anti-KIR4.1 antibody (green) but not in OHCs, which were specifically identified by anti-prestin antibodies (green). The shape of OHCs was outlined by (C). No CEACAM16 staining could be detected in Ceacam16−/− mice (A, inset). Note the staining for CEACAM16 in both the cell body and projections of the Deiters cells (open arrows in A and D), which extend to the reticular lamina (arrows in C), the stiff cover of the organ of Corti. The locations of the Deiters cell nuclei are indicated by full arrows (B and D). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Furthermore, staining for CEACAM16 was observed in the supranuclear (neck) region of IHCs (outlined by the stippled line) and in pillar cells (G and H). Pillar cells were identified by staining with anti-KIR4.1 antibody. A schematic representation of OHCs and Deiters cells is shown in I. Magnification bars, 10 μm. BM, basilar membrane; DC, Deiters cell; DP, Deiters cell projection; PC, pillar cell; RL, reticular lamina; SC, stereocilia.

FIGURE 8.

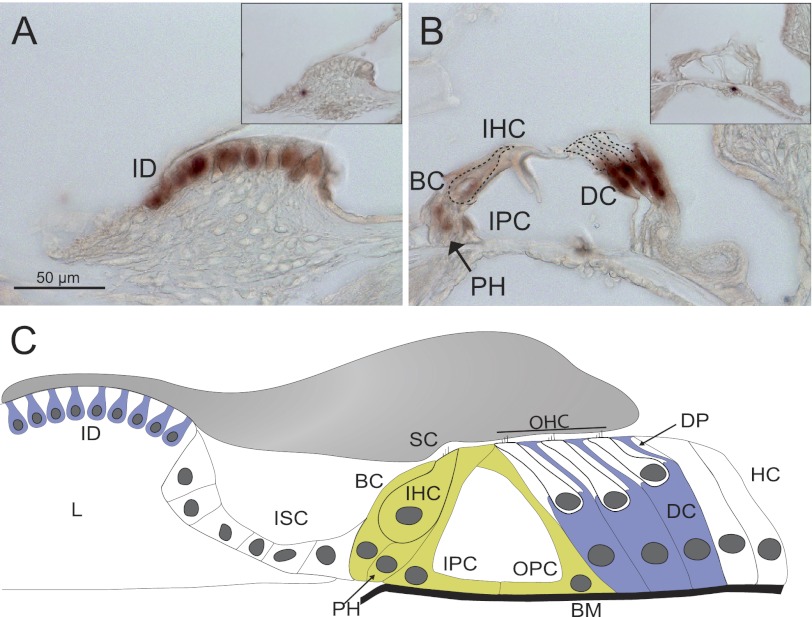

Ceacam16 mRNA is expressed in interdental and Deiters cells. Expression of Ceacam16 in the organ of Corti of young rats (P12) was analyzed by in situ hybridization of cochlear sections with a Ceacam16 antisense probe. Strong expression of Ceacam16 mRNA (brown) appears in interdental cells of the limbus (A) and in Deiters cells and to a lesser extent in phalangeal, border, pillar, and inner hair cells (B). The shape of the inner and outer hair cells is indicated by broken lines. No specific staining was observed with the sense probe (insets in A and B). C, shown is a schematic representation of Ceacam16 mRNA expression with color-coded expression levels (green, weak expression; blue, strong expression). BM, basilar membrane; BC, border cell; DC, Deiters cell; DP, Deiters cell projection; HC, Hensen's cell; ID, interdental cell; IHC, inner hair cells; IPC, inner pillar cell; ISC, inner sulcus cell; L, limbus; OHC, outer hair cells; OPC, outer pillar cell; PH, phalangeal cell; SC, stereocilia.

CEACAM16 Is Deposited Late during TM Development

Deposition of proteinaceous components of the TM starts already prenatally at about embryonic day (E) 14 in mice (25). Maturation of the TM is observed around postnatal day 15 (P15) a time point in development where mature mechanical and electrical cochlear responses are observed (26). The major components of the TM comprise three types of collagen (collagen II, IX, XI), α-tectorin, and β-tectorin, the most abundant non-collagenous proteins as well as otogelin and otolin (27, 28). Transcription of the various tectorial proteins can occur in various cell types, and their temporal expression pattern differs (e.g. Tecta transcription ceases at P15) (29). To learn more about the possible functional interplay of CEACAM16 with other components of the TM, we determined its spatiotemporal expression pattern in the organ of Corti in young mice (P5-P18) at the protein and RNA level. Immunohistological analyses revealed that CEACAM16 could not be detected in P5, P8, and P10 cochleae (compare Fig. 6, A–C, with D–F). However, at P12 and occasionally at P15, CEACAM16 was found in both the limbal zone and in the marginal band of the TM, whereas in the medial zone only the sulcus proximal side of the TM was stained (Fig. 6, G and J). At P18 and often already at P15, the TM exhibited homogenous staining for CEACAM16 (Fig. 6, H and K, and Fig. 6, I and L). Despite the presence of background staining in some samples, comparison of wild-type sections with sections from Ceacam16−/− mice stained in parallel suggest that both interdental cells and Deiters cells and possibly OHCs might be the source of the CEACAM16 protein (compare Fig. 6, G, H, and I with J, K, and L). Quantitation of Ceacam16 and Tecta transcripts by quantitative RT-PCR analyses demonstrated persistent transcriptional activity of Ceacam16 from P12 into adulthood and an inverse temporal expression activity of Tecta (Fig. 6M). In contrast, the stereocilin gene (Strc) is only marginally expressed in the cochlea during the developmental time frame investigated (Fig. 6M).

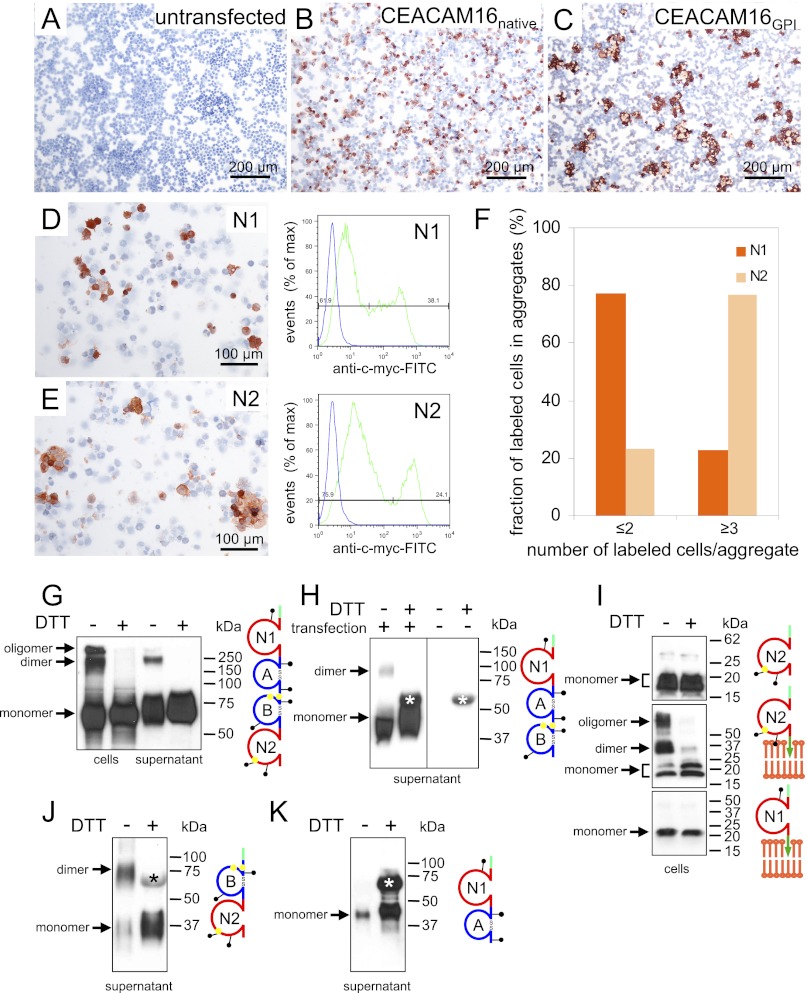

Homotypic Interactions of CEACAM16

We had noticed during characterization of the anti-CEACAM16 antibodies where we used transient transfection to express GPI-anchored CEACAM16 on the cell surface to screen sera and hybridoma supernatants by a cell-based ELISA that single-cell suspensions of HEK293T cells expressing GPI-anchored CEACAM16 aggregated homotypically, whereas cells expressing native CEACAM16 did not (Fig. 9, A–C). These findings suggested that CEACAM16 molecules might interact in an antiparallel fashion also under physiological conditions possibly involving the N1 or N2 domain. Such IgV-like domains are known to be instrumental for homo- and heterophilic interaction of CEACAM family members (30). To test this we expressed N1 and N2 domains separately via a GPI anchor on the cell surface of HEK293T cells by transient transfection and analyzed single cell suspensions for their propensity to aggregate. Although the fraction of cells expressing high levels of N1 (38%) was higher than that observed for N2 transfectants (24%) (Fig. 9, D and E, right panels), the N2 transfectants formed more and larger N2-expressing cell aggregates in the presence of 50% untransfected cells added to the aggregation assay (Fig. 9, D–F). Notably, no aggregates >9 cells were observed for N1 transfectants, whereas 38% of N2-expressing cells were contained in such aggregates (not shown). This suggests that the N1 domain exhibits a weaker homophilic interaction (if any) than the N2 domain.

FIGURE 9.

CEACAM16 interacts homotypically. HEK293T cells either remained untransfected (A) or were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding full-length murine native (B) or GPI-linked CEACAM16 (C). The transfected cells were harvested by repeated pipetting, incubated at room temperature, attached to glass slides using the cytospin method, and stained with anti-murine CEACAM16 immune sera by immunocytochemistry (brown stain). Note the homotypic sorting of cells expressing CEACAM16 on the cell membrane (C) but not of cells with intracellular expression (B). This suggests that CEACAM16 can interact homotypically in trans. Aggregation of HEK293T cells was tested as above after transient expression of GPI-anchored human CEACAM16 N1 and N2 domains (D and E, left panels). N1- and N2-expressing cells were detected by immunocytochemistry using an anti-myc-tag antibody. Representative regions of the cytospins are shown. The expression levels of myc-tagged fusion proteins and the fraction of positive cells were determined by FACScan analysis using anti-myc and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (D and E, right panels, green curves). Samples incubated without primary antibody served as a negative control (blue curves). Aggregation mediated by N1 and N2 domains was quantitated by determination of the fraction of N1- and N2-positive cells, respectively, in single and double cell populations as well as in aggregates ≥3 using the cytospins shown in D and E (F). Note that surface expression of N2 preferentially induces multicellular aggregates. One of two experiments with similar results is shown. Full-length murine native CEACAM16 (G) or a deletion constructs lacking N2 (H) or N1 and A (J) or B and N2 (K) or encoding only the N1 or N2 domain either soluble (I, upper panel) or GPI-linked (I, lower panels) were expressed in HEK293T cells by transient transfection. Cell lysates (cells) or cell culture supernatants with or without prior treatment with DTT were separated by gel electrophoresis, and CEACAM16 was detected by Western blot analysis with a monoclonal anti-myc antibody. The domain organization of the encoded proteins is schematically shown to the right. Cysteines possibly involved in intermolecular disulfide bridges are indicated by yellow dots, green tags represent NH2-terminally added myc epitopes, and green arrows symbolize GPI anchors. Presumed monomeric, dimeric, and oligomeric forms of CEACAM16 are indicated by arrows. Note that the N2 or the N1 and A domains appear to be dispensable for interaction as dimers are observed in the absence of these domains (J). The 60-kDa band. which is observed in the supernatant of transfected and mock-transfected cells (H, right panel), is marked by an asterisk (H, J, and K).

Furthermore, we wanted to know whether the phylogenetically highly conserved unpaired cysteine residues in the B and N2 domains (supplemental Fig. 4) would be suitable to support oligomerization of CEACAM16. To this end we modeled the Ig-like domains of human CEACAM16. Cys-253 and Cys-294 of the B domain were predicted to be located inside of the domain in close proximity thus allowing intra-domain disulfide bridge formation, whereas Cys-239 and Cys-258 are predicted to emerge from the surface possibly allowing oligomerization in cis and/or in trans (supplemental Fig. 5, A and B). In the N2 domain, however, Cys-387 appears to be located in a depression and thus seems to less likely allow intermolecular disulfide bond formation (supplemental Fig. 5, C and D). To test the hypothesis, we expressed full-length murine CEACAM16 transiently on HEK293T cells. Western blot analysis of cell extracts and cell culture supernatants revealed that in the absence of the disulfide-reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT), CEACAM16 dimers and oligomers could be detected that, however, disappeared upon heating with DTT and were converted to monomers (Fig. 9G). Dimers were also observed in the supernatants when deletion constructs lacking the N2 or both the N1 and the A domain were used (Fig. 9, H and J). As expected, a COOH-terminal-truncated CEACAM16 consisting of N1 and A with no unpaired cysteines did not form dimers (Fig. 9K). This indicated that CEACAM16 can dimerize via intermolecular disulfide bonds between B and/or N2 domains also in the absence of the N1 and A or the N2 domain. Similar dimer and oligomer formation were observed in cell extracts when full-length or CEACAM16 deletion mutants were ectopically expressed on the cell surface via a GPI anchor that probably supports parallel interaction on the membrane (data not shown). To test whether the single cysteine in the N2 domain can form a disulfide bridge between two N2 domains, we analyzed HEK293T cells expressing secreted or GPI-linked N2 or N1 domains. The latter has no cysteine and served as a negative control. As expected, no dimers were observed for N1, whereas higher molecular weight molecule species were observed for the GPI-linked N2 domain, which disappeared upon DTT treatment (Fig. 9I, lower and middle panels). Dimers could not be seen either in cell extracts or supernatants when soluble N2 domains were expressed (Fig. 9I, upper panel and data not shown). These data together with the observation that N2 can support cell adhesion when ectopically expressed on the cell membrane (Fig. 9, E and F) indicate that N2 can interact in cis and trans but possibly can form a disulfide bridge only when aligned in parallel.

DISCUSSION

With the conquest of land by formerly aquatic vertebrates, adaptation to the new medium air included development of the cochlear auditory system. Highly complex sensory structures evolved (i.e. the organ of Corti) probably from the vestibular system (31). This organ consists of inner and outer hair cells sandwiched between specialized extracellular matrices, namely the basilar membrane and the TM. Hair cells sense the sound-induced vibrations of the basilar membrane. Inner hair cells transmit this information to the central nervous system via auditory nerves. Outer hair cells transform their vibrational stimulation via a voltage-dependent molecular motor into length changes and possibly also stereocilia motion that together with the TM as a physical support help to amplify the basilar membrane motion. In mammals, this amplification mechanism increases the sensitivity of hearing by up to 50–60 db (32).

From our studies of Ceacam16−/− mice we conclude that the mammal-specific CEA family member CEACAM16 is involved in hearing. In Ceacam16−/− mice hearing is impaired already at a young age (∼4 weeks old). This impairment is reflected by an increased hearing threshold for low and high frequency pure tone stimuli and reduced cochlear amplification, which is likely to result from a reduced mechanical force within the cochlea rather than a sensory-neural hearing loss. This loss is maintained over a long period of the lifespan when age-related sensory-neural hearing loss additionally affects the threshold in knock-out and in wild-type mice (Fig. 4). Noise exposure led to a somehow smaller loss of hearing function in Ceacam16−/− mice as compared with the loss in Ceacam16+/+ mice, indicating that vulnerability to cochlear trauma is not increased by loss of the CEACAM16 protein in the cochlea. In contrast, a reduced mechanical coupling of OHC motility into the cochlear amplifier under normal conditions, improving detection of close threshold auditory stimuli, may account for the reduced noise vulnerability in Ceacam16−/− mice.

This is corroborated by a recent publication where it was shown that affected individuals of an American family (1070) with non-syndromic autosomal dominant hearing impairment (DFNA4) progressing during adulthood to ∼50 db, carry a missense mutation in the CEACAM16 gene (33). The phenotype of affected individuals is very similar to that observed for Ceacam16−/− mice. Thus our study adds evidence that the DFNA4 mutation is indeed the cause of this specific hearing impairment in humans and probably leads to loss of function of CEACAM16. The non-syndromic nature of CEACAM16 mutations in humans and mice are explained by the highly restricted expression of CEACAM16 mRNA in the cochlea in both species (Fig. 1, supplemental Fig. 1). No obvious phenotypes relating to the trace amounts of Ceacam16 mRNA found in the cerebellum and pituitary of mice were observed.

The type of hearing impairment in Ceacam16−/− mice is reminiscent of the phenotype observed for mice with Tecta and Tectb functional null mutations. Tecta and Tectb encode the inner ear-specific proteins α-tectorin and β-tectorin, major non-collagenous proteins of the otoconia membrane and TM. Loss of low frequency hearing has been reported for Tectb null mice (<20 kHz) (34). Furthermore, mice with a Tecta functional null mutation (TectaΔENT/ΔENT) similarly exhibit an increased compound action potential threshold preferentially at lower frequencies (35). Indeed, CEACAM16 protein could also be detected in the acellular matrices of the cochlea and the saccule, i.e. the TM and the otolith-containing acellular gel, respectively. OHC-supporting cells (Deiters cells) as well as interdental cells in the limbus region appear to be the source of CEACAM16 protein production in young mice (Figs. 5 and 6). In adult mice (P49) cell-associated CEACAM16 could be unequivocally identified in Deiters cells as well as in pillar cells and inner hair cells from where CEACAM16 is possibly released via the Deiters cells projections and reaches the TM by diffusion (Fig. 7). This apparently contradicts findings of Zheng et al. (33) who detected Ceacam16 transcripts in OHCs by in situ hybridization in 42-day-old mice. This can possibly be explained by visual overlap of OHCs and Deiters cell compartments in the in situ experiment of Zheng et al. (33). Indeed, we could demonstrate the presence of Ceacam16 transcripts in Deiters cells, interdental cells, pillar cells, and possibly in inner hair cells by in situ hybridization using sections cut in parallel to the outer hair cell-Deiters cell axis (Fig. 8). In addition, our data demonstrate that, in comparison to α-tectorin, CEACAM16 protein is deposited in the TM rather late during development of the inner ear. α-Tectorin mRNA amounts in the cochleae drop rapidly after birth, reaching base-line levels in P15 mice, a time point where peak levels of CEACAM16 mRNA were observed (Fig. 6M) (29). This might explain the finding that in mice, at hearing onset (P14-P15) a higher compound action potential threshold is observed (26) that could be due to TM immaturity caused by incomplete deposition of CEACAM16 in the TM at this time of development. CEACAM16 appears to be evenly distributed not until an age of P15-P18 (Fig. 6). In contrast to Tecta, Ceacam16 transcription continues into adulthood. Besides continued expression in Deiters cells, CEACAM16 production is possibly shifted in adult mice to cells in the lateral wall (e.g. stria vascularis) and secreted into the endolymph as suggested by the presence of CEACAM16 mRNA in human lateral wall preparations (Fig. 1). This, however, could not be corroborated by in situ hybridization experiments using adult mouse cochleae (data not shown). Therefore, this discrepancy regarding CEACAM16 expression in mouse and humans remains unresolved and still has to be clarified.

CEACAM16 was suggested to represent the link structure within the TM that connects α-tectorin, to which CEACAM16 binds, with the tip of the stereocilia (33). Participation of α-tectorin in the linkage of the TM to the stereocilia was postulated by Legan et al. (35), as in TectaΔENT/ΔENT functionally null mice complete detachment of the TM from the organ of Corti is observed. If CEACAM16 were the postulated bridging partner connecting α-tectorin with the suggested counterpart stereocilin on the stereocilia (36), Ceacam16−/− mice should have the same phenotype as Tecta mutant mice with respect to attachment of the TM to the stereocilia. To the contrary, in Ceacam16−/− mice the TM seems to be often connected to the organ of Corti specifically to the OHCs (see Fig. 5, F and H). Furthermore, stereocilin is detected in the tallest row of stereocilia of OHCs by P7 (36), a time point in development when stereocilia become associated with the TM and stereocilin deposition on the TM is observed (36). At this time CEACAM16 is still absent from the murine TM (Fig. 6).

Rather, based on our data, we suggest that CEACAM16 is part of the striated-sheet structure. The detachment of the TM from the OHCs in wild-type but not in Ceacam16−/− mice during preparation and fixation of the cochlea suggests that CEACAM16 might be involved in the generation of TM elasticity (Fig. 5). The TM is composed of two main structural components; that is, thick radially arranged 20-nm fibrils made of collagens II and IX that are embedded in a finely striated-sheet matrix composed of about 7-nm wide alternating dark and light fibrils with a repeat width of 30–46 nm (37). α-Tectorin and β-tectorin but not otogelin, an additional noncollagenous component of the TM, are essential for the formation of the striated-sheet matrix as the lack of expression of the former two proteins leads to loss of an organized striated-sheet matrix (34, 35, 38). Because there is convincing evidence that CEACAM16 interacts with α-tectorin (33) and probably can form oligomers via homophilic interaction stabilized by disulfide bridges (Fig. 9), it can be envisaged that CEACAM16 is part of the striated-sheet matrix and forms possibly the darker of the two discernible fibrils and the much longer α-tectorin together with β-tectorin possibly by interaction via their zona pellucida (ZP) domains, known as protein polymerization domains (39), the lighter fibril with emanating staggered cross-bridges (supplemental Fig. 6). This is also in agreement with the observed sensitivity of the striated-sheet matrix toward disulfide bridge-disrupting agents (37).

The TM ultrastructure of mammals differs from that of birds (31). Interestingly, in addition to collagens II and IX, the striated-sheet matrix within the TM is not found in chickens and thus appears to be restricted to the mammalian lineage. This coincides with the restriction of CEACAM16 but not TECTA and TECTB genes to mammals. Because the mammalian basilar membrane extended in length and decreased in width to increase the frequency range, the appearance of CEACAM16 and mammal-specific collagens in the TM during evolution may have provided the correct physical properties to the TM that it can amplify the motion of the basilar membrane at its characteristic resonance frequencies and thus enhance the sensitivity of mammalian hearing (31).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge continuous support by the animal facilities of the Gene Center and the Walter Brendel Center of Experimental Medicine, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich. We thank Tanja Popp, Birgit Stadlbauer, and Beata Rutz for excellent technical assistance and Kyung-Jin Lee and Alexander Buchner for help with the hearing experiments and statistical analysis, respectively.

This work was supported in part by the FöFoLe program of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Munich, and is part of the doctoral theses of Constanze Schäuble, Rosemarie Krupar, and Annegret Kamp at the University of Munich.

This article contains supplemental Table 1 and Figs. 1–6.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) NM_001039213 and NM_001033419.

W. Zimmermann and R. Kammerer, unpublished results.

- CEA

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- CEACAM1

- CEA-related cell-cell adhesion molecule 1

- TM

- tectorial membrane

- ES cell

- embryonic stem cell

- ABR

- auditory brainstem responses

- DPOAE

- distortion products of the otoacoustic emissions

- SPL

- sound pressure level

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- OHC

- outer hair cell

- IHC

- inner hair cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kammerer R., Zimmermann W. (2010) Coevolution of activating and inhibitory receptors within mammalian carcinoembryonic antigen families. BMC Biol. 8, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kammerer R., Stober D., Singer B. B., Obrink B., Reimann J. (2001) Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 on murine dendritic cells is a potent regulator of T cell stimulation. J. Immunol. 166, 6537–6544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leung N., Turbide C., Balachandra B., Marcus V., Beauchemin N. (2008) Intestinal tumor progression is promoted by decreased apoptosis and dysregulated Wnt signaling in Ceacam1−/− mice. Oncogene 27, 4943–4953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerstel D., Wegwitz F., Jannasch K., Ludewig P., Scheike K., Alves F., Beauchemin N., Deppert W., Wagener C., Horst A. K. (2011) CEACAM1 creates a pro-angiogenic tumor microenvironment that supports tumor vessel maturation. Oncogene 30, 4275–4288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee S. J., Heinrich G., Fedorova L., Al-Share Q. Y., Ledford K. J., Fernstrom M. A., McInerney M. F., Erickson S. K., Gatto-Weis C., Najjar S. M. (2008) Development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in insulin-resistant liver-specific S503A carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 mutant mice. Gastroenterology 135, 2084–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li C., Chen C. J., Shively J. E. (2009) Mutational analysis of the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1–4L in humanized mammary glands reveals key residues involved in lumen formation. Stimulation by Thr-457 and inhibition by Ser-461. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1225–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pan H., Shively J. E. (2010) Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1 regulates granulopoiesis by inhibition of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. Immunity 33, 620–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gray-Owen S. D., Blumberg R. S. (2006) CEACAM1. Contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee H. S., Ostrowski M. A., Gray-Owen S. D. (2008) CEACAM1 dynamics during Neisseria gonorrhoeae suppression of CD4+ T lymphocyte activation. J. Immunol. 180, 6827–6835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slevogt H., Zabel S., Opitz B., Hocke A., Eitel J., N'guessan P. D., Lucka L., Riesbeck K., Zimmermann W., Zweigner J., Temmesfeld-Wollbrueck B., Suttorp N., Singer B. B. (2008) CEACAM1 inhibits Toll-like receptor 2-triggered antibacterial responses of human pulmonary epithelial cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1270–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuespert K., Pils S., Hauck C. R. (2006) CEACAMs. Their role in physiology and pathophysiology. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 565–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pils S., Gerrard D. T., Meyer A., Hauck C. R. (2008) CEACAM3. An innate immune receptor directed against human-restricted bacterial pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 298, 553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarantis H., Gray-Owen S. D. (2007) The specific innate immune receptor CEACAM3 triggers neutrophil bactericidal activities via a Syk kinase-dependent pathway. Cell Microbiol. 9, 2167–2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zebhauser R., Kammerer R., Eisenried A., McLellan A., Moore T., Zimmermann W. (2005) Identification of a novel group of evolutionarily conserved members within the rapidly diverging murine Cea family. Genomics 86, 566–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tan K., Zelus B. D., Meijers R., Liu J. H., Bergelson J. M., Duke N., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Holmes K. V., Wang J. H. (2002) Crystal structure of murine sCEACAM1a[1,4]. A coronavirus receptor in the CEA family. EMBO J. 21, 2076–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obrink B. (1991) C-CAM (cell-CAM 105). A member of the growing immunoglobulin superfamily of cell adhesion proteins. Bioessays 13, 227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kammerer R., Riesenberg R., Weiler C., Lohrmann J., Schleypen J., Zimmermann W. (2004) The tumor suppressor gene CEACAM1 is completely but reversibly down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. J. Pathol. 204, 258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conrad M., Brielmeier M., Wurst W., Bornkamm G. W. (2003) Optimized vector for conditional gene targeting in mouse embryonic stem cells. Biotechniques 34, 1136–1138, 1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Noben-Trauth N., Köhler G., Bürki K., Ledermann B. (1996) Efficient targeting of the IL-4 gene in a BALB/c embryonic stem cell line. Transgenic Res. 5, 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finkenzeller D., Fischer B., Lutz S., Schrewe H., Shimizu T., Zimmermann W. (2003) Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 10 expressed specifically early in pregnancy in the decidua is dispensable for normal murine development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 272–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Knipper M., Zinn C., Maier H., Praetorius M., Rohbock K., Köpschall I., Zimmermann U. (2000) Thyroid hormone deficiency before the onset of hearing causes irreversible damage to peripheral and central auditory systems. J. Neurophysiol. 83, 3101–3112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schimmang T., Tan J., Müller M., Zimmermann U., Rohbock K., Kôpschall I., Limberger A., Minichiello L., Knipper M. (2003) Lack of Bdnf and TrkB signaling in the postnatal cochlea leads to a spatial reshaping of innervation along the tonotopic axis and hearing loss. Development 130, 4741–4750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Engel J., Braig C., Rüttiger L., Kuhn S., Zimmermann U., Blin N., Sausbier M., Kalbacher H., Münkner S., Rohbock K., Ruth P., Winter H., Knipper M. (2006) Two classes of outer hair cells along the tonotopic axis of the cochlea. Neuroscience 143, 837–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Combet C., Jambon M., Deléage G., Geourjon C. (2002) Geno3D. Automatic comparative molecular modeling of protein. Bioinformatics 18, 213–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lim D. J. (1987) Development of the tectorial membrane. Hear. Res. 28, 9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verpy E., Weil D., Leibovici M., Goodyear R. J., Hamard G., Houdon C., Lefèvre G. M., Hardelin J. P., Richardson G. P., Avan P., Petit C. (2008) Stereocilin-deficient mice reveal the origin of cochlear waveform distortions. Nature 456, 255–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thalmann I. (1993) Collagen of accessory structures of organ of Corti. Connect. Tissue Res. 29, 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deans M. R., Peterson J. M., Wong G. W. (2010) Mammalian Otolin. A multimeric glycoprotein specific to the inner ear that interacts with otoconial matrix protein Otoconin-90 and cerebellin-1. PLoS One 5, e12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rau A., Legan P. K., Richardson G. P. (1999) Tectorin mRNA expression is spatially and temporally restricted during mouse inner ear development. J. Comp. Neurol. 405, 271–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klaile E., Vorontsova O., Sigmundsson K., Müller M. M., Singer B. B., Ofverstedt L. G., Svensson S., Skoglund U., Obrink B. (2009) The CEACAM1 N-terminal Ig domain mediates cis- and trans-binding and is essential for allosteric rearrangements of CEACAM1 microclusters. J. Cell Biol. 187, 553–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goodyear R. J., Richardson G. P. (2002) Extracellular matrices associated with the apical surfaces of sensory epithelia in the inner ear. Molecular and structural diversity. J. Neurobiol. 53, 212–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ryan A., Dallos P. (1975) Effect of absence of cochlear outer hair cells on behavioral auditory threshold. Nature 253, 44–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zheng J., Miller K. K., Yang T., Hildebrand M. S., Shearer A. E., DeLuca A. P., Scheetz T. E., Drummond J., Scherer S. E., Legan P. K., Goodyear R. J., Richardson G. P., Cheatham M. A., Smith R. J., Dallos P. (2011) Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 16 interacts with α-tectorin and is mutated in autosomal dominant hearing loss (DFNA4). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4218–4223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Russell I. J., Legan P. K., Lukashkina V. A., Lukashkin A. N., Goodyear R. J., Richardson G. P. (2007) Sharpened cochlear tuning in a mouse with a genetically modified tectorial membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 215–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Legan P. K., Lukashkina V. A., Goodyear R. J., Kössi M., Russell I. J., Richardson G. P. (2000) A targeted deletion in α-tectorin reveals that the tectorial membrane is required for the gain and timing of cochlear feedback. Neuron 28, 273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verpy E., Leibovici M., Michalski N., Goodyear R. J., Houdon C., Weil D., Richardson G. P., Petit C. (2011) Stereocilin connects outer hair cell stereocilia to one another and to the tectorial membrane. J. Comp. Neurol. 519, 194–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasko J. A., Richardson G. P. (1988) The ultrastructural organization and properties of the mouse tectorial membrane matrix. Hear. Res. 35, 21–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simmler M. C., Cohen-Salmon M., El-Amraoui A., Guillaud L., Benichou J. C., Petit C., Panthier J. J. (2000) Targeted disruption of otog results in deafness and severe imbalance. Nat. Genet. 24, 139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jovine L., Darie C. C., Litscher E. S., Wassarman P. M. (2005) Zona pellucida domain proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 83–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]