Abstract

PURPOSE

Zirconia has been used in clinical dentistry for approximately a decade, and there have been several reports regarding the clinical performance and survival rates of zirconia-based restorations. The aim of this article was to review the literatures published from 2000 to 2010 regarding the clinical performance and the causes of failure of zirconia fixed partial dentures (FPDs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An electronic search of English peer-reviewed dental literatures was performed through PubMed to obtain all the clinical studies focused on the performance of the zirconia FPDs. The electronic search was supplemented by manual searching through the references of the selected articles for possible inclusion of some articles. Randomized controlled clinical trials, longitudinal prospective and retrospective cohort studies were the focuses of this review. Articles that did not focus on the restoration of teeth using zirconia-based restorations were excluded from this review.

RESULTS

There have been three studies for the study of zirconia single crowns. The clinical outcome was satisfactory (acceptable) according to the CDA evaluation. There have been 14 studies for the study of zirconia FPDs. The survival rates of zirconia anterior and posterior FPDs ranged between 73.9% - 100% after 2 - 5 years. The causes of failure were veneer fracture, ceramic core fracture, abutment tooth fracture, secondary caries, and restoration dislodgment.

CONCLUSION

The overall performance of zirconia FPDs was satisfactory according to either USPHS criteria or CDA evaluations. Fracture resistance of core and veneering ceramics, bonding between core and veneering materials, and marginal discrepancy of zirconia-based restorations were discussed as the causes of failure. Because of its repeated occurrence in many studies, future researches are essentially required to clarify this problem and to reduce the fracture incident.

Keywords: Zirconia fixed partial denture, Clinical performance, Failure, Cause of failure

INTRODUCTION

All-ceramic fixed partial dentures (FPDs) have been routinely used in clinical dentistry because various all-ceramic materials have been introduced and available for a clinical use. Favorable clinical performance for all-ceramic systems, has been reported especially when they are used in the anterior region.1 However, fractures of posterior all-ceramic FPDs occurred and have been reported as a main cause of failure for these restorations.2 To overcome this problem, ceramics with different compositions and reinforcing crystalline phases have been developed, such as a glass-infiltrated zirconia-toughened alumina, a lithium-disilicate-based glass-ceramic, and zirconia-based materials. Most of the zirconia-based ceramic systems that are currently used in dentistry are yttrium-stabilized zirconia polycrystals (3Y-TZP).3 This zirconia contains 3 mol% of yttria (Y2O3) as a stabilizer. The major advantage of this material is their high fracture resistance which represents by their superior flexural strength (900-1000 MPa) and fracture toughness (5.5 - 7.4 MPa·m1/2) compared with other all-ceramic core materials.4 The processing procedures of 3Y-TZP usually use a CAD-CAM technology for machining a presintered zirconia blank to a desired size and shape of a prosthesis and subsequent firing at 1350 - 1550℃ is carried out to produce a densely sintered product. Compensation for 20 - 30% firing shrinkage is made during a CAD procedure. Magnesium-stabilized zirconia (Mg-PSZ) has also been used with a limited success due to the presence of porosity, associated with a large grain size (30 - 60 µm) that can induce wear.3 The microstructure of Mg-PSZ consists of tetragonal precipitates within a cubic stabilized zirconia matrix which can result in lower mechanical properties and a less stable material. Denzir-M® (Dentronic AB) is an example of Mg-PSZ ceramic currently available for hard machining of dental restorations.

An introduction of zirconia-based core ceramics provides more predictable treatment options for the posterior teeth where the high chewing loads are applied. The CAD/CAM technology also allows the possibility of using either partially or fully sintered zirconium dioxide blanks to fabricate frameworks and copings. Not only the fabricating technology that makes zirconia-based ceramics a material of choice for fabrication of FPDs, the high fracture resistance of zirconia-based materials that could withstand high occlusal loads has been the major advantage of these materials. Because zirconia has been used in clinical dentistry for approximately a decade, there have been several reports regarding the clinical performance and survival rates of zirconiabased restorations. The aim of this article was to review the literatures published from 2000 to 2010 regarding the clinical performance of zirconia FPDs and the causes of failure were discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An electronic search of English peer-reviewed dental literatures was performed through PubMed to obtain all the clinical studies on the performance of the zirconia FPDs. The keywords or phrases for the search were zirconia, restoration, fixed partial dentures, crowns, zirconium dioxide, failure, clinical performance. The PubMed searches were conducted focusing on research articles published from 2000 to 2010. The electronic search was supplemented by manual searching through the references of the selected articles for possible inclusion of some articles. Randomized controlled clinical trials, longitudinal prospective and retrospective cohort studies were the focuses of this review. The abstracts of searched articles were initially reviewed for possible inclusion by three reviewers. Then the full text articles were obtained for assessment. Articles that did not focus on the restoration of teeth using zirconia-based restorations were excluded from this review.

RESULTS

Clinical performance of single crowns

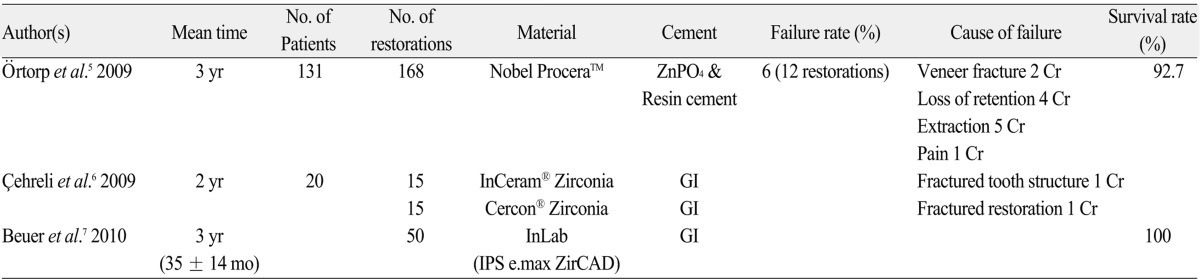

There have been three studies for the study of zirconia single crowns (Table 1). In the 3-year retrospective clinical study of 168 zirconia single crowns by Örtorp et al.5, the clinical outcome was satisfactory (acceptable) according to the CDA evaluation. Most crowns (78%) were placed in the premolar or molar area. There was no secondary caries and no ceramic core fracture. Extraction of the five abutment teeth occurred because of one root fracture and four endodontic and periodontal complications. Four veneer fractures were observed and two crowns were remade from this problem. Loss of retention was reported for 12 crowns and four new crowns were remade. The persistent pain occurred in one patient and a new crown was remade for this patient. The cumulative survival rate was 92.7% after 3 years. Çehreli et al.6 studied the clinical performance of zirconia crowns in the premolar and molar regions and reported no clinical sign of marginal discoloration, persistent pain and secondary caries. The clinical outcome was acceptable according to the CDA evaluation. However, one catastrophic crown fracture was reported in this study and immediately replaced with a new zirconia crown. The favorable results were obtained for the third studies as no failures were recorded from the fifty crowns observed within the group of single crown.7

Table 1.

Clinical performance of zirconia crown

Clinical performance of zirconia fixed partial dentures

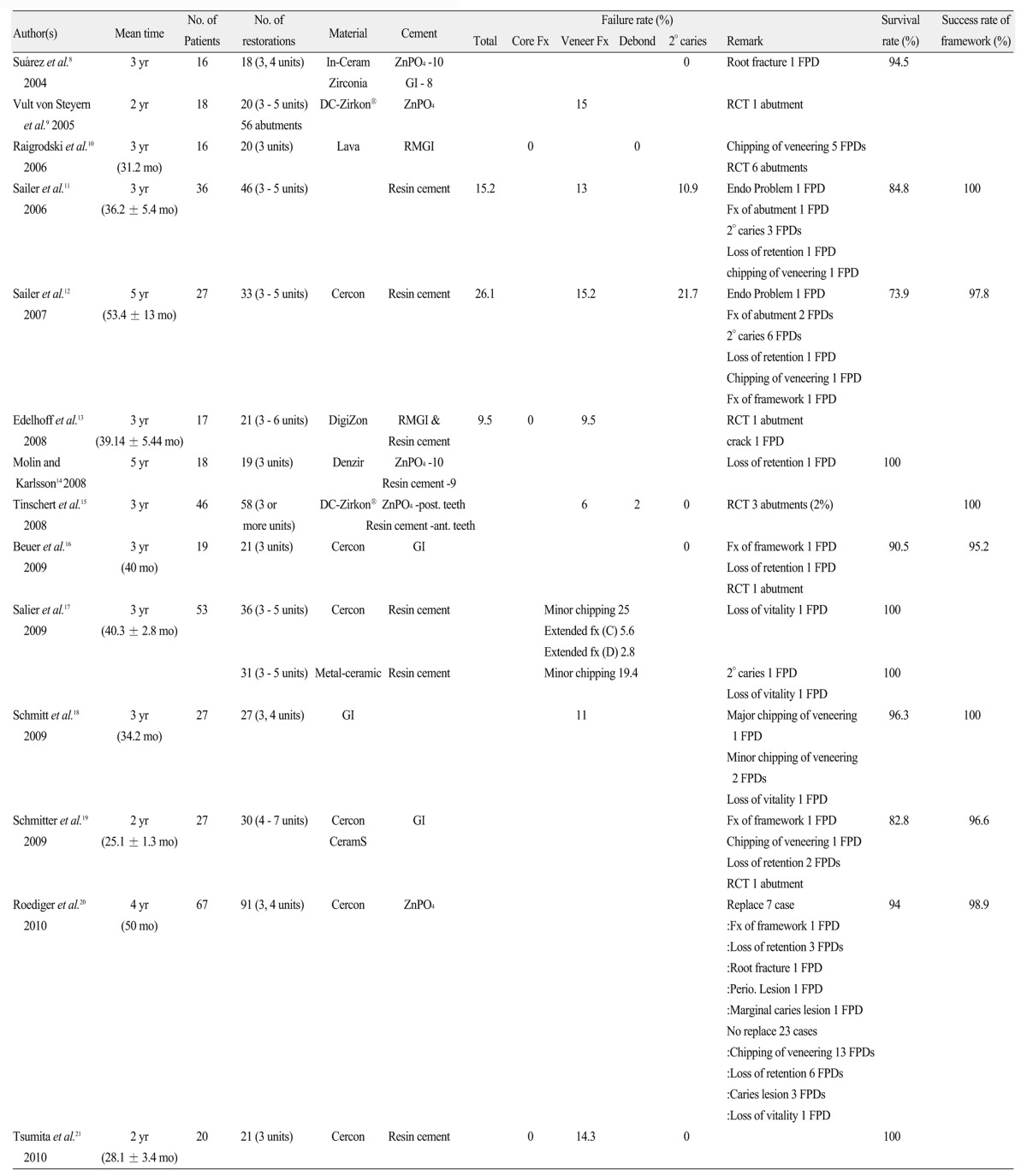

There have been 14 studies that included in this review (Table 2).8-21 Zirconia core materials and systems that have been used in those clinical studies are shown in Table 3. The survival rates of zirconia anterior and posterior FPDs ranged between 73.9% - 100% after 2 - 5 years. The causes of failure were veneer fracture, ceramic core fracture, abutment tooth fracture, secondary caries, and restoration dislodgment. Core fracture was found in four studies.12,16,19,20 Veneer fracture was found in 11 studies either reported as minor or major chipping, and the veneer fracture rate could be as high as 25%.8-12,14,17-21 The rate of veneer fracture was varied as some studies did not include minor chipping in the failure rate. High secondary caries rates were observed in two studies using a zirconia fabricated with a CAM system.11,12 Fracture of the abutment teeth and endodontic problem were found in 48,11,12,20 and 11 studies,9-13,15-20 respectively. The overall performance of anterior and posterior FPDs was satisfactory according to either USPHS criteria or CDA Evaluations. According to the causes of failures previously mentioned, the material-related factors that involved in the failure development of zirconia all-ceramic prostheses were the fracture resistance of core and veneering ceramics, bonding between core and veneering materials, and marginal discrepancy of zirconia-based restorations.

Table 2.

Clinical performance of zirconia fixed partial denture

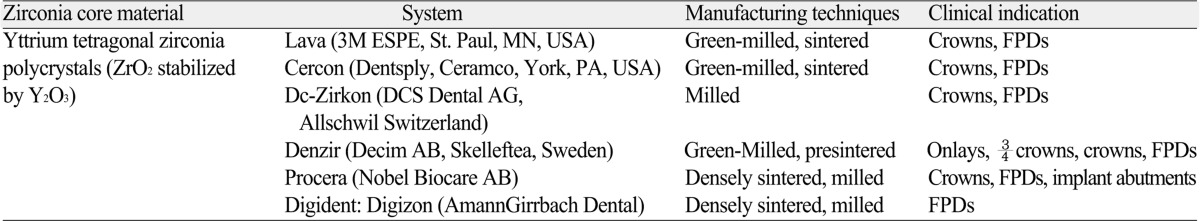

Table 3.

Zirconia core materials and systems and manufacturer-recommended clinical indications

Core fracture

Ceramics are brittle materials. Because of their brittleness, a catastrophic fracture can occur without or with minimal plastic deformation when they are subjected to a critical tensile load. This behavior has made ceramics a unique group among other materials. The fracture resistance of ceramics is normally represented by their fracture strength and fracture toughness. Because fracture strength depends on several factors such as testing types and conditions, material's size and shape22 etc., it is difficult to use this parameter for comparing the results between different studies or materials. Therefore, fracture toughness is more practical because it is an inherent material property and should not be changed with the different testing conditions and environments.22 For zirconia-based core ceramics, their fracture toughness values range between 5.5 to 7.4 MPa·m1/2 which are much higher than other all-ceramic core materials.4 The toughening process for zirconia is the unique transformation toughening mechanism.3 This mechanism includes the transformation of tetragonal to monoclinic phase of TZP zirconia when they are subjected to loading and an increase in material volume during the transformation. An increase in volume from the monoclinic phase induces compressive stress around the crack tip and inhibits crack propagation which results in an increase in fracture resistance of these materials. Because of their superior fracture resistance, fracture of zirconia core ceramic is infrequent. The causes of fracture observed from the reviewed studies were not from the material itself but the fracture occurred from a trauma and parafunctional habit. However, the thickness of coping is a factor that influences the success of a restoration, so it should be designed following the manufacturer's recommendations. The connector size of zirconia frameworks should be at least 9 mm2 to withstand clinical loading in the posterior teeth.9,10,13,14,19-21 Another demanding behavior of zirconia material is its long-term behavior under subcritical stress in real clinical situations. Susceptibility to subcritical crack growth of some zirconia materials could increase the fracture probability after long-term loading in simulated oral conditions.23

Veneer fracture

The critical problem that has been observed in most studies is fracture or chipping of a veneering material. Fracture of veneering ceramics or dental porcelains could be separated into two groups, fracture of a veneering itself and fracture originated from the interfaces between the core and veneering porcelains. Most veneering ceramics or dental porcelains have low fracture toughness (KIc) values (0.7 - 0.9 MPa·m1/2) which are at least eight times lower than that of the zirconia core ceramics because their main composition is based on glass compositions.24 Therefore, compositions of veneering porcelains are not varied much between different brands.25 However, these materials are still used in dental applications because of their esthetic advantages. A conventional condensation and sintering technique used in fabricating a veneer can also contribute in low fracture resistance of veneering materials because it can produce a great number of porosity that can lower the strength and can create a critical flaw for fracture to occur. Not only the processing procedures that can induce defects into ceramic materials, chewing stress applied during mastication also can produce surface damage on a restoration because it directly contacts with the food particles or opposing teeth. During mastication, dental restorations are subjected to cyclic and variable rates of loading, and crack initiation can occur on the contact surfaces and lead to fatigue failure. Improving or adjusting the compositions or processing methods is difficult because it may affect porcelain color and translucency. Adding of some crystalline phases, such as leucite crystal, to increase the fracture resistance has been used in some veneering porcelains.26 The amount of leucite added into dental porcelain is usually less than 22 vol% because an increase in crystal volume fraction would decrease the translucency of a material.27 Heat treatment of bilayer ceramics to the temperature near the glass transition temperature of the veneer and then cooled rapidly to room temperature could produce residual compressive stresses within the veneer layer which provided a strengthening effect for a veneer layer. While the residual tensile stress caused from slow cooling could decrease the fracture resistance of a veneer layer especially when combining with the local residual tensile stresses caused from contact damage.28 The residual tensile stresses can also develop due to the thermal expansion mismatch between the core and veneer and the viscoelastic properties of a glass veneer during sintering. These residual tensile stresses developed from either causes can lower the fracture resistance of a veneering material. The thermally compatible core-veneer system has been suggested to have a thermal contraction mismatch approximately ≤ 1.0 ppm/K.29 Generally, a brand of veneering porcelain is produced for a group of thermally compatible zirconia core ceramics (Δα≤ 1.0 ppm/K). The use of thermally incompatible core and veneer materials could result in delamination or weakening of the veneer layer.29 Moreover, the coefficients of linear thermal expansion of core and veneer materials had linear correlation with glass transition temperatures of the veneering ceramics. The residual stresses, expressed by these two factors, could compromise fracture strength of these ceramic bilayer systems.30 Many factors affect the core-veneer bond strength of zirconia-based prostheses such as types of core or veneering ceramic, surface finish of the core, application of a liner and a method of veneering application. For a zirconia core and a compatible veneering ceramic obtained from the same manufacturer, the bond strength of a bilayer ranged between 26 to 37 MPa which were comparable to the veneer strengths.31,32 For other all-ceramic systems, their bond strength ranged between 32 to 45 MPa.33 Different brands of zirconia core generated different bond strengths even when the same veneering ceramic was used.32 Different brands of veneering ceramics also produced various numbers of bond strength when they were used with the same zirconia core ceramic.31 The surface finish of a zirconia framework and liners could also produce an adverse effect on core-veneer bond strength.31,32 Sandblasting and application of a liner would be recommended for some zirconia cores, not for all zirconia materials. The coloring pigments deposited at the grain boundaries also affected the grain structure and bond strength of zirconia core ceramics.32 A reduction in bond strength between the zirconia core and veneer could also be caused by a slow cooling rate during sintering of veneer and liner materials.28,34 Slow cooling from the sintering temperature to a room temperature could weaken the bond strength of zirconia core and veneer because it generated residual tensile stresses resulted from a viscoelastic relaxation of a glass phase contained in a veneering ceramic.28,34

Although there are many zirconia core ceramics available for framework fabrication, there is limited information about previously mentioned factors that could affect bonding between zirconia cores and veneering ceramics. The method of selection a zirconia core and a compatible veneering ceramic is not clear even manufacturers provide a list of compatible materials for both core and veneering ceramics. Theoretically, the differences in the coefficient of linear thermal expansion are evaluated as a primary guideline for material selection for a layer composite. However, the thermally compatible systems appear to be not adequate for selecting a well-matched zirconia core and veneer as many factors can affect their core-veneer bond strength. Future researches are essentially required to clarify this problem and to establish the acceptable criteria for a core-veneer material combination.

Marginal discrepancy of zirconia-based restorations

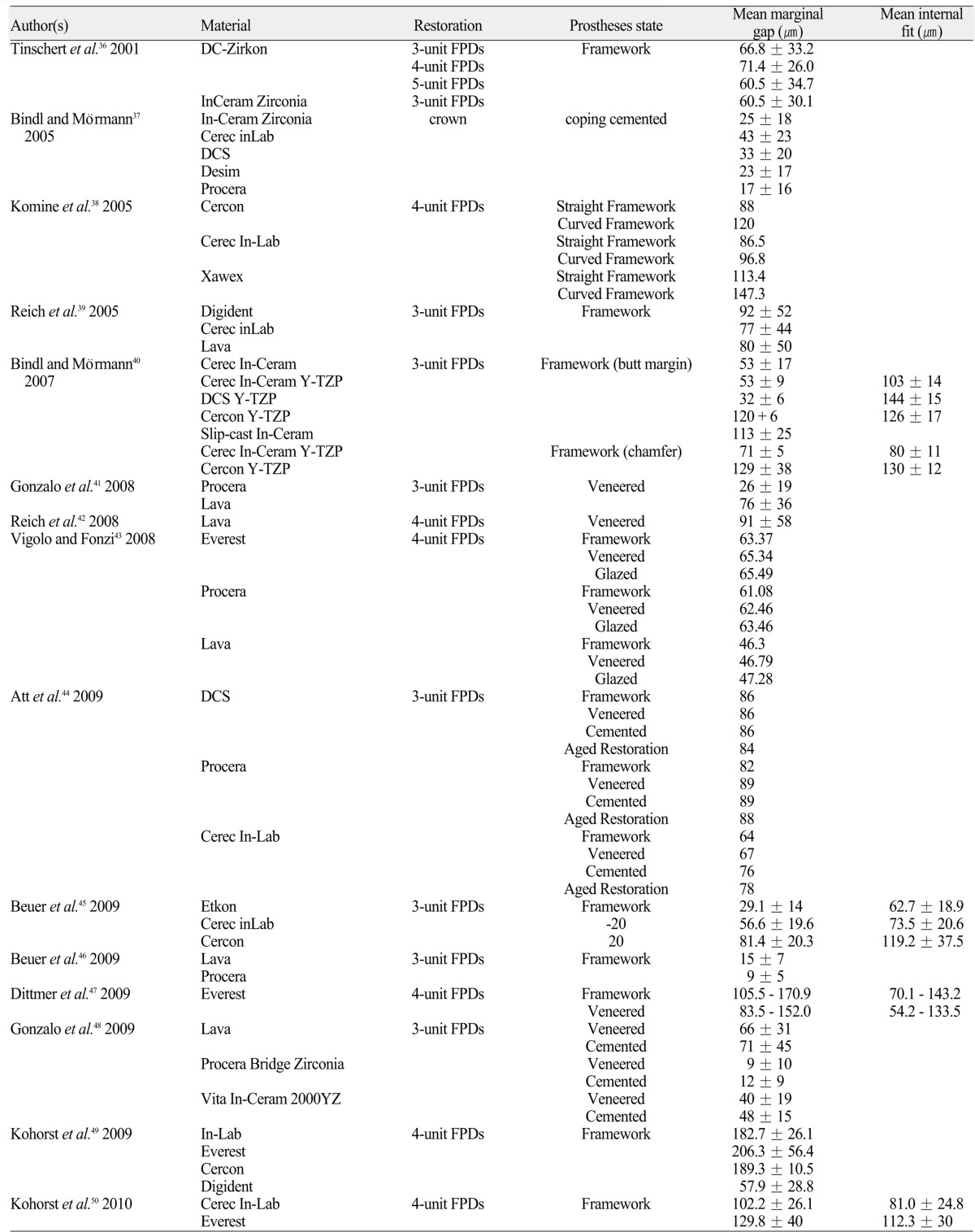

Marginal discrepancy of all-ceramic restorations is a vital factor that affects the longevity of dental restorations. Excessive marginal gap width could lead to cement leakage, secondary caries, periodontal and endodontic complications which could compromise the survival of a restoration or an abutment tooth.35 Currently, computer-aided design and computer-aided machine systems (CAD-CAM) are generally available for processing of all-ceramic prostheses, especially for zirconia-based dental prostheses. Different fabricating systems used in the CAD-CAM processing techniques could lead to varied results in term of the marginal and internal gap width (Table 4).36-50 In addition, span length, framework configuration, and veneering ceramic could affect the fit of zirconia FPDs. Even there has been some inconsistency between the results obtained from a number of studies, CAD-CAM system appeared to provide more accurate marginal and internal fit of zirconia frameworks compared to CAM system.40,45 The results from two in vivo studies also reported a complication (dental caries) which could be a result from an unacceptable margin fabricated from a CAM system.11,12 Post-sintered milling or hard machining is expected to be more predictable for more complex geometry and / or longer span FPDs than the pre-sintered zirconia frameworks because there is no firing shrinkage associated with the fabrication process.40,49 However, the prolonged milling time and high wear rate of the milling tools are its major disadvantages of post-sintered milling.

Table 4.

Mean marginal gap and internal fit of zirconia-based restorations

CONCLUSION

According to the results from the reviewed clinical studies, zirconia frameworks have been shown that they could provide a strong support to a veneering layer because of their high fracture resistance. Because all zirconia frameworks were fabricated from different CAD-CAM systems, it appeared that these CAD-CAM systems could also provide acceptable frameworks in terms of the design and accurate margin. Fracture of veneering ceramics was observed in many studies, but it was not the major causes for the replacement with a new restoration as it could be adjusted and polished. The causes of veneering fracture regarding the veneer properties could be the differences in thermally incompatible, elastic and viscoelastic behaviors of core and veneering ceramics, or a firing pattern of veneering materials. Because of its repeated occurrence in many studies, future researches are essentially required to clarify this problem and to reduce the fracture incident.

References

- 1.Haselton DR, Diaz-Arnold AM, Hillis SL. Clinical assessment of high-strength all-ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson KG, Fürst B, Andersson B, Carlsson GE. A long-term retrospective and clinical follow-up study of In-ceram alumina FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:150–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denry I, Kelly JR. State of the art of zirconia for dental applications. Dent Mater. 2008;24:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guazzato M, Albakry M, Ringer SP, Swain MV. Strength, fracture toughness and microstructure of a selection of all-ceramic materials. Part II. Zirconia-based dental ceramics. Dent Mater. 2004;20:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2003.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Örtorp A, Kihl ML, Carlsson GE. A 3-year retrospective and clinical follow-up study of zirconia single crowns performed in a private practice. J Dent. 2009;37:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Çehreli MC, Kökat AM, Akça K. CAD/CAM Zirconia vs. slip-cast glass-infiltrated Alumina/Zirconia all-ceramic crowns: 2-year results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:49–55. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beuer F, Stimmelmayr M, Gernet W, Edelhoff D, Güh JF, Naumann M. Prospective study of zirconia-based restorations: 3-year clinical results. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:631–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suárez MJ, Lozano JF, Paz Salido M, Martínez F. Three-year clinical evaluation of In-Ceram Zirconia posterior FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vult von Steyern P, Carlson P, Nilner K. All-ceramic fixed partial dentures designed according to the DC-Zirkon technique. A 2-year clinical study. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raigrodski AJ, Chiche GJ, Potiket N, Hochstedler JL, Mohamed SE, Billiot S, Mercante DE. The efficacy of posterior three-unit zirconium-oxide-based ceramic fixed partial dental prostheses: a prospective clinical pilot study. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sailer I, Fehér A, Filser F, Lüthy H, Gauckler LJ, Schärer P, Franz Hämmerle CH. Prospective clinical study of zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: 3-year follow-up. Quintessence Int. 2006;37:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sailer I, Fehér A, Filser F, Gauckler LJ, Lüthy H, Hämmerle CH. Five-year clinical results of zirconia frameworks for posterior fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelhoff D, Florian B, Florian W, Johnen C. HIP zirconia fixed partial dentures-clinical results after 3 years of clinical service. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:459–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molin MK, Karlsson SL. Five-year clinical prospective evaluation of zirconia-based Denzir 3-unit FPDs. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinschert J, Schulze KA, Natt G, Latzke P, Heussen N, Spiekermann H. Clinical behavior of zirconia-based fixed partial dentures made of DC-Zirkon: 3-year results. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beuer F, Edelhoff D, Gernet W, Sorensen JA. Three-year clinical prospective evaluation of zirconia-based posterior fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) Clin Oral Investig. 2009;13:445–451. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sailer I, Gottnerb J, Kanelb S, Hammerle CH. Randomized controlled clinical trial of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic posterior fixed dental prostheses: a 3-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt J, Holst S, Wichmann M, Reich S, Gollner M, Hamel J. Zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: a prospective clinical 3-year follow-up. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitter M, Mussotter K, Rammelsberg P, Stober T, Ohlmann B, Gabbert O. Clinical performance of extended zirconia frameworks for fixed dental prostheses: two-year results. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:610–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roediger M, Gersdorff N, Huels A, Rinke S. Prospective evaluation of zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: four-year clinical results. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsumita M, Kokubo Y, Ohkubo C, Sakurai S, Fukushima S. Clinical evaluation of posterior all-ceramic FPDs (Cercon): a prospective clinical pilot study. J Prosthodont Res. 2010;54:102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertzberg RW. Deformation and fracture mechanics of engineering materials. 4th ed. NewYork; USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1995. pp. 326–327. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tinschert J, Natt G, Mohrbotter N, Spiekermann H, Schulze KA. Lifetime of alumina- and zirconia ceramics used for crown and bridge restorations. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;80:317–321. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Pallav P, Isgrò G, Feilzer AJ. Fracture toughness comparison of three test methods with four dental porcelains. Dent Mater. 2007;23:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suputtamongkol K, Tulapornchai C, Teanchai C. Composition and properties of three dental porcelains. Mahidol Dent J. 2008;28:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cesar PF, Yoshimura HN, Miranda Júnior WG, Okada CY. Correlation between fracture toughness and leucite content in dental porcelains. J Dent. 2005;33:721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong JL, Farley DW, Norling BK. Quantification of leucite concentration using X-ray diffraction. Dent Mater. 2000;16:20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(99)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taskonak B, Borges GA, Mecholsky JJ, Jr, Anusavice KJ, Moore BK, Yan J. The effects of viscoelastic parameters on residual stress development in a zirconia/glass bilayer dental ceramic. Dent Mater. 2008;24:1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeHoff PH, Anusavice KJ. Viscoelastic finite element stress analysis of the thermal compatibility of dental bilayer ceramic systems. Int J Prosthodont. 2009;22:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer J, Stawarczyk B, Tomic M, Strub JR, Hämmerle CH. Effect of thermal misfit between different veneering ceramics and zirconia frameworks on in vitro fracture load of single crowns. Dent Mater J. 2007;26:766–772. doi: 10.4012/dmj.26.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Part II: Zirconia veneering ceramics. Dent Mater. 2006;22:857–863. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Effect of zirconia type on its bond strength with different veneer ceramics. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aboushelib MN, de Jager N, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Dent Mater. 2005;21:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Göstemeyer G, Jendras M, Dittmer MP, Bach FW, Stiesch M, Kohorst P. Influence of cooling rate on zirconia/veneer interfacial adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4532–4538. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Felton DA, Kanoy BE, Bayne SC, Wirthman GP. Effect of in vivo crown margin discrepancies on periodontal health. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:357–364. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90225-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tinschert J, Natt G, Mautsch W, Spiekermann H, Anusavice KJ. Marginal fit of alumina-and zirconia-based fixed partial dentures produced by a CAD/CAM system. Oper Dent. 2001;26:367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bindl A, Mörmann WH. Marginal and internal fit of all-ceramic CAD/CAM crown-copings on chamfer preparations. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komine F, Gerds T, Witkowski S, Strub JR. Influence of framework configuration on the marginal adaptation of zirconium dioxide ceramic anterior four-unit frameworks. Acta Odontol Scand. 2005;63:361–366. doi: 10.1080/00016350500264313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reich S, Wichmann M, Nkenke E, Proeschel P. Clinical fit of all-ceramic three-unit fixed partial dentures, generated with three different CAD/CAM systems. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:174–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bindl A, Mörmann WH. Fit of all-ceramic posterior fixed partial denture frameworks in vitro. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2007;27:567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalo E, Suárez MJ, Serrano B, Lozano JF. Marginal fit of zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:398–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reich S, Kappe K, Teschner H, Schmitt J. Clinical fit of fourunit zirconia posterior fixed dental prostheses. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:579–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vigolo P, Fonzi F. An in vitro evaluation of fit of zirconium-oxide-based ceramic four-unit fixed partial dentures, generated with three different CAD/CAM systems, before and after porcelain firing cycles and after glaze cycles. J Prosthodont. 2008;17:621–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Att W, Komine F, Gerds T, Strub JR. Marginal adaptation of three different zirconium dioxide three-unit fixed dental prostheses. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;101:239–247. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beuer F, Aggstaller H, Edelhoff D, Gernet W, Sorensen J. Marginal and internal fits of fixed dental prostheses zirconia retainers. Dent Mater. 2009;25:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beuer F, Naumann M, Gernet W, Sorensen JA. Precision of fit: zirconia three-unit fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Investig. 2009;13:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s00784-008-0224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dittmer MP, Borchers L, Stiesch M, Kohorst P. Stresses and distortions within zirconia-fixed dental prostheses due to the veneering process. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:3231–3239. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalo E, Suárez MJ, Serrano B, Lozano JF. A comparison of the marginal vertical discrepancies of zirconium and metal ceramic posterior fixed dental prostheses before and after cementation. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;102:378–384. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohorst P, Brinkmann H, Li J, Borchers L, Stiesch M. Marginal accuracy of four-unit zirconia fixed dental prostheses fabricated using different computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing systems. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohorst P, Brinkmann H, Dittmer MP, Borchers L, Stiesch M. Influence of the veneering process on the marginal fit of zirconia fixed dental prostheses. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37:283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]