Abstract

The dispersal mechanism of Geomyces destructans, which causes geomycosis (white nose syndrome) in hibernating bats, remains unknown. Multiple gene genealogic analyses were conducted on 16 fungal isolates from diverse sites in New York State during 2008–2010. The results are consistent with the clonal dispersal of a single G. destructans genotype.

Keywords: fungi, fungal infection, bats, Geomyces destructans, white nose syndrome, population biology, New York, dispatch

Geomycosis, or white nose syndrome, is a newly recognized fungal infection of hibernating bats. The etiologic agent, the psychrophilic fungus Geomyces destructans, was first recognized in caves and mines around Albany, New York, USA (1,2). The disease has spread rapidly in New York and other states in the northeastern United States. At least 1 affected bat species is predicted to face regional extinction in the near future (3). Much remains unknown about this fungus, including its ecology and geographic distribution. For example, although hibernacula are high on the list of suspected sites, where the bats acquire this infection is not known. Similarly, although strongly suspected, the role of humans and other animals in the dispersal of G. destructans and the effect of such dispersals in bat infections have not been confirmed. We recently showed that 6 G. destructans strains from sites near Albany were genetically similar (2), raising the possibility of a common source for the spread of this infection. Corollary to this observation and other opinions (3,4), the US Fish & Wildlife Service has made an administrative decision to bar human access to caves as a precautionary measure (www.fws.gov/whitenosesyndrome/pdf/NWRS_WNS_Guidance_Final1.pdf). Thus, an understanding of the dispersal mechanism of G. destructans is urgently needed to formulate effective strategies to control bat geomycosis.

The Study

We applied multiple gene genealogic analyses in studying G. destructans isolates; this approach yields robust results that are easily reproduced by other laboratories (5). Sixteen G. destructans isolates recovered from infected bats during 2008–2010 were analyzed. These isolates originated from 7 counties in New York and an adjoining county in Vermont, all within a 500-mile radius (Table 1). The details of isolation and identification of G. destructans from bat samples have been described (2). One isolate of a closely related fungus G. pannorum M1372 (University of Alberta Mold Herbarium, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) was included as a reference control. To generate molecular markers, 1 isolate, G. destructans (M1379), was grown in yeast extract peptone dextrose broth at 15°C, and high molecular weight genomic DNA was prepared according to Moller et al. (6). A cosmid DNA library was constructed by using pWEB kit (Epicenter Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA) by following protocols described elsewhere (7). One hundred cosmid clones, each with ≈40-Kb DNA insert, were partially sequenced in both directions by using primers M13 and T7. The nucleotide sequences were assembled with Sequencher 4.6 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) homology searches identified 37 putative genes. Sequences of 10 genes, including open reading frames, 3′ and/or 5′ untranslated regions, and introns, were evaluated as potential markers for analyzing G. pannorum and G. destructans. Our screening approach indicated that 8 gene targets could be amplified from both G. destructans and G. pannorum by PCR (Table 2).

Table 1. Geomyces destructans isolates studied, New York, USA.

| Isolate |

Date obtained |

Site, county* |

|---|---|---|

| M1379† | 2008 Mar 28 | Williams Hotel Mine, Ulster |

| M1380† | 2008 Mar 28 | Williams Hotel Mine, Ulster |

| M1381† | 2008 Mar 28 | Williams Hotel Mine, Ulster |

| M1383† | 2008 Apr 11 | Graphite Mine, Warren |

| M2325 | 2010 Jan 25 | Westchester |

| M2327 | 2010 Feb 2 | Dewitt, Onondaga |

| M2330 | 2009 Mar 5 | Lancaster, Erie |

| M2331 | 2009 Mar 9 | White Plains, Westchester |

| M2332 | 2009 Mar 11 | Dannemora, Clinton |

| M2333 | 2009 Mar 11 | Dannemora, Clinton |

| M2334 | 2009 Mar 12 | Newstead, Erie |

| M2335 | 2009 Mar 16 | Ithaca, Tompkins |

| M2336 | 2009 Oct 6 | Bridgewater Mine, Windsor, VT |

| M2337 | 2010 Feb 9 | Akron Mine, Erie |

| M2338 | 2010 Mar 4 | Hailes Cave, Albany |

| M2339 | 2010 Mar 11 | Letchworth Tunnel, Livingston |

*All locations in New York state except Bridgewater Mine, Windsor, Vermont. †Previously analyzed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA typing.

Table 2. Geomyces destructans and G. pannorum target gene fragments used for multiple gene genealogic analyses, New York, USA.

| Gene* | Homology (GenBank accession no.) | Amplicon size/ sequence used for comparison, bp | Primer sequence, 5′ → 3′† | G. destructans/G. pannorum GenBank accession nos. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ALR

|

Penicillium

marneffei (XP_002152078.1) |

654/534 |

V1905 (f): CGGAGTGAGATTTATGACGGC |

HQ834314–HQ834329/HQ834330 |

| V1904 (r):

CGTCCATCCCAGACGTTCATC | ||||

|

Bpntase

|

Glomerella

graminicola (EFQ33509.1) |

921/745 |

V1869 (f): TCAGACGGACTCGGAGGGCAAG |

HQ834331–HQ834346/HQ834347 |

| V1926 (r):

TCGGTTACAGAGCCTCAGTCG | ||||

|

DHC1

|

Sordaria

macrospora (CBI53717.1) |

597/418 |

V1906 (f): GGATGATTCGGTCACCAAACAG |

HQ834348–HQ834363/HQ834364 |

| V1907 (r):

ACAGCAAACACAGCGCTGCAAG | ||||

|

GPHN

|

Ajellomyces

capsulatus (EEH06836.1) |

659/525 |

V1918 (f): CACTATTACATCGCCAGGCTC |

HQ834365–HQ834380/HQ834381 |

| V1919 (r):

CTAAACGCAGGCACTGCCTC | ||||

|

PCS

|

A.

capsulatus

(EEH08767.1) |

920/749 |

V1929 (f): AGGCTGCGATTGCTGAGTGC |

HQ834382–HQ834397/HQ834398 |

| V1873 (r):

CCTTATCCAGCTTTCCTTGGTC | ||||

|

POB3

|

Pyrenophora

tritici-repentis (XP_001937502.1) |

653/417 |

V1908 (f): CACAGTGGAGCAAGGCATCC |

HQ834399–HQ834414/HQ834415 |

| V1909 (r):

ACATACCTAGGCGTCAAGTGC | ||||

|

SRP72

|

A.

dermatitidis (EEQ90678.1) |

941/640 |

V1927 (f): AAGGGAAGGTTGGAGAGACTC |

HQ834416–HQ834431/HQ834432 |

| V1895 (r):

CAAGCAGCATTGTACGCCGTC | ||||

| VPS13 | Verticillium albo-atrum (XP_003001174.1) | 665/545 | V1922 (f): GAGACAACGCTTGTTTGCAAGG | HQ834433–HQ834448/HQ834449 |

| V1923 (r): ACATGCGTCGTTCCAAGATCTG |

*Genes: ALR, α-L-rhamnosidase; Bpntase, 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase; DHC1, Dynein heavy chain; GPHN, Gephyrin, molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein; PCS, peroxisomal-coenzyme A synthetase; POB3, FACT complex subunit; SRP72, signal recognition particle protein 72; VPS13, vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein. †f, forward; r, reverse.

To obtain DNA sequences from 1 G. pannorum and 16 G. destructans isolates, we prepared genomic DNA from mycelia grown in yeast extract peptone dextrose broth through conventional glass bead treatment and phenol-chloroform extraction and then ethanol precipitation (7). AccuTaq LA DNA Polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for PCR: 3 min initial denaturation at 94°C, 35 amplification cycles with a 15-sec denaturation at 94°C, 30-sec annealing at 55°C, and 1-min extension at 68°C and a 5-min final extension at 68°C. PCR products were treated with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA) before sequencing. Both strands of amplicons were sequenced by the same primers used for PCR amplification (Table 2). A database was created by using Microsoft Access (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) to deposit and analyze the sequences. Nucleotide sequences were aligned with ClustalW version 1.4 (www.clustal.org) and edited with MacVector 7.1.1 software (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA). Phylogenetic analyses were done by using PAUP 4.0 (8) and MEGA 4 (9).

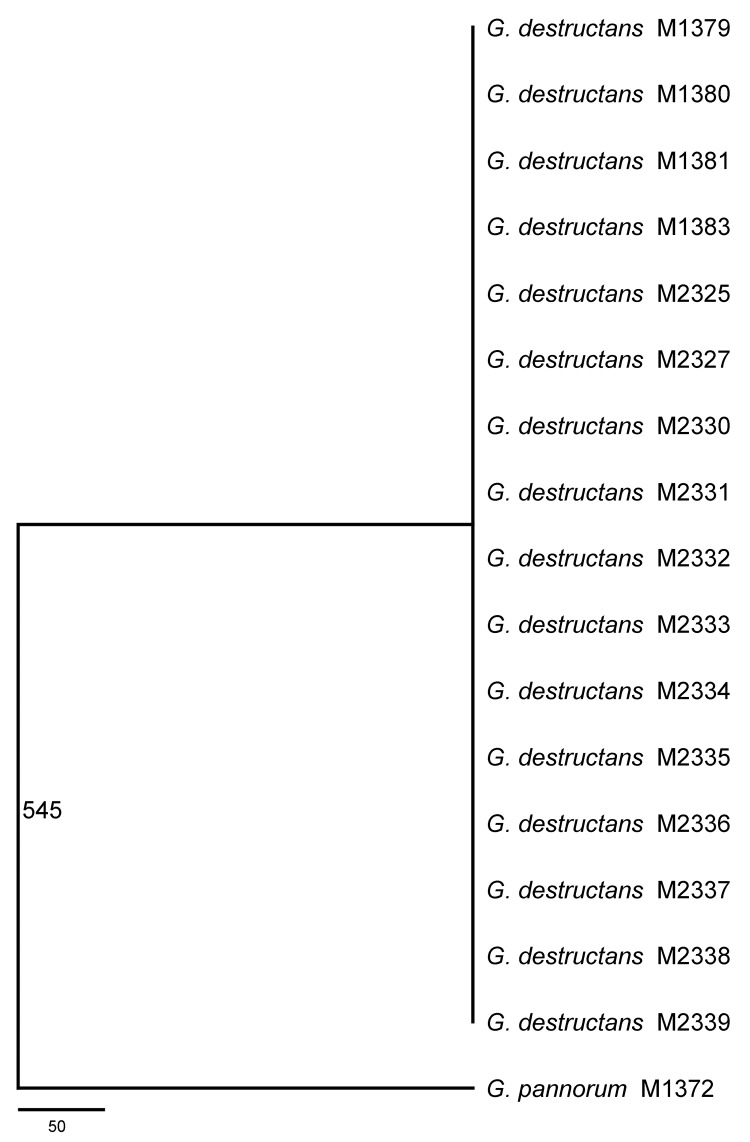

We cloned and sequenced ≈200 Kb of the G. destructans genome and identified genes involved in a variety of cellular processes and metabolic pathways (Table 2). DNA sequence typing by using 8 gene fragments showed that all 16 G. destructans isolates had identical nucleotide sequences at all 8 sequenced gene fragments but were distinct from G. pannorum sequences. A maximum-parsimony tree generated from the 8 concatenated gene fragments indicated a single, clonal genotype for the 16 G. destructans strains (Figure 1). This consensus tree included 4,470 aligned nucleotides from all targeted gene sequences with 545 variable sites that separate the G. destructans clonal genotype from G. pannorum. Further analyses of the same concatenated gene fragments with exclusion of 50 insertions and deletions between G. destructans and G. pannorum yielded a tree with a shorter length (495 steps instead of 545 steps) but an identical topology (Technical Appendix Figure 1). This pattern remained unchanged when different phylogenetics models were used for analysis (Technical Appendix Figure 2). The lack of polymorphism among the 16 G. destructans isolates was unlikely because of evolutionary constraint at the sequenced gene fragments. We found many synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in target genes among a diversity of fungal species, including between G. destructans and G. pannorum (10) (Technical Appendix Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Consensus maximum-parsimony tree derived from analyzing 8 concatenated gene fragments including a total of 4,470 aligned nucleotides by using PAUP* 4.0 (8). The number 545 on the branch indicates the total number of variable nucleotide positions (out of the 4,470 nt) separating Geomyces pannorum M1372 from the clonal genotype of G. destructans identified here. Fifty of the 545 variable sites correspond to insertions and deletions. Scale bar indicates number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Conclusions

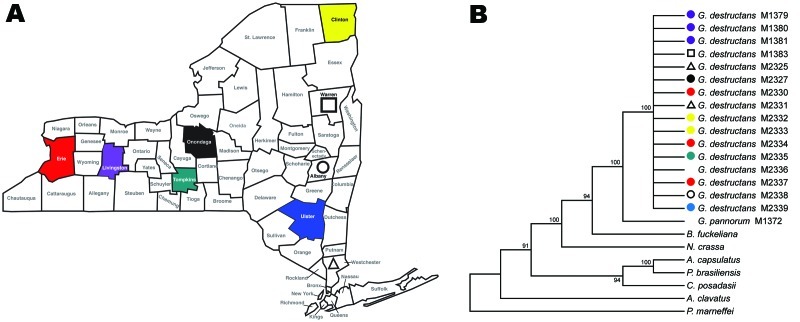

Our finding of a single clonal genotype in G. destructans population fits well with the rapid spread of geomycosis in New York (Figure 2). Our sampling population covered both spatial and temporal dimensions, and the numbers of isolates analyzed were adequate in view of difficulties encountered in obtaining pure isolations of G. destructans (11). Although the affected New York sites are separated by sizable distances and include geographic barriers, a role for the natural dissemination of the fungus through air, soil, and water cannot be ruled out. Indeed, several fungi with geographic distributions similar to that in our study have shown major genetic variation among strains (12,13). It is also possible that humans and/or animals contributed to the rapid clonal dispersal. In such a scenario, the diseased or asymptomatic bats might act as carriers of the fungus by their migration into new hibernation sites where new animals get infected and the dissemination cycle continues (4). Similarly, the likely roles played by humans and/or other animals in the transfer of the fungal propagules from an affected site to a clean one cannot be ruled out from our data.

Figure 2.

Collection sites in New York counties (A) are color-matched with respective Geomyces destructans isolates in maximum-parsimony tree based on nucleotide sequence of the VPS13 gene (B). The tree was constructed with MEGA4 (9) by using 450 nt and bootstrap test with 500 replicates. In addition to G. destructans and G. pannorum, fungi analyzed were Ajellomyces capsulatus (AAJI01000550.1), Aspergillus clavatus NRRL 1 (AAKD03000035.1), Botryotinia fuckeliana B05.10 (AAID01002173.1), Coccidioides posadasii C735 delta SOWgp (ACFW01000049.1), Neurospora crassa OR74A (AABX02000023.1), Paracoccidioides brasiliensis Pb01 (ABKH01000209.1), and Penicillium marneffei ATCC 18224 (ABAR01000009.1).

Virulent clones of human and plant pathogenic fungi that spread rapidly among affected populations have been recognized with increasing frequency in recent years (12,14). However, other pathogens, such as the frog-killing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, have emerged with both clonal and recombining populations (13). Our data do not eliminate the possibility that the G. destructans population undergoes recombination in nature. This process to generate genetic variability would require some form of sexual reproduction, which remains unknown in G. destructans. In addition, the fungus might have both asexual and sexual modes in its saprobic life elsewhere in nature, but it exists only in asexual mode on bats (15).

In conclusion, our data suggest that a single clonal genotype of G. destructans has spread among affected bats in New York. This finding might be helpful for the professionals involved in devising control measures. Many outstanding questions remain about the origin of G. destructans, its migration, and reproduction, all of which will require concerted efforts if we are to save bats from predicted extinction (3).

Supplementary Material

Maximum-parsimony trees figures and Multiple alignments of 8 target gene fragments figure.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomic Technologies Core for DNA sequencing and Media, Glassware and Tissue Culture Unit for specialized culture media. We thank Jared Mayron for creating a Microsoft Access database.

Biography

Dr Rajkumar is a postdoctoral research affiliate in the Mycology Laboratory at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York, USA. His research interests are molecular genetics, genomics, and antifungal drugs.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Rajkuma SS, Li X, Rudd RJ, Okoniewski JC, Xu J, Chaturvedi S, et al. Clonal genotype of Geomyces destructans among bats with white nose syndrome, New York, USA. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1707.102056

References

- 1.Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science. 2009;323:227. 10.1126/science.1163874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi V, Springer DJ, Behr MJ, Ramani R, Li X, Peck MK, et al. Morphological and molecular characterizations of psychrophilic fungus Geomyces destructans from New York bats with white nose syndrome (WNS). PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10783. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frick WF, Pollock JF, Hicks AC, Langwig KE, Reynolds DS, Turner GG, et al. An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common North American bat species. Science. 2010;329:679–82. 10.1126/science.1188594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallam TG, McCracken GF. Management of the panzootic white-nose syndrome through culling of bats. Conserv Biol. 2011;25:189–94. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu J. Fundamentals of fungal molecular population genetic analyses. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2006;8:75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Möller EM, Bahnweg G, Sandermann H, Geiger HH. A simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6115–6. 10.1093/nar/20.22.6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren P, Roncaglia P, Springer DJ, Fan JJ, Chaturvedi V. Genomic organization and expression of 23 new genes from MAT alpha locus of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:233–41. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swafford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony *and other methods. Sutherland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–9. 10.1093/molbev/msm092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasuga T, White TJ, Taylor JW. Estimation of nucleotide substitution rates in eurotiomycete fungi. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:2318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wibbelt G, Kurth A, Hellmann D, Weishaar M, Barlow A, Veith M, et al. White-nose syndrome fungus (Geomyces destructans) in bats, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1237–43. 10.3201/eid1608.100002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hovmøller MS, Yahyaoui AH, Milus EA, Justesen AF. Rapid global spread of two aggressive strains of a wheat rust fungus. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:3818–26. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan JAT, Vredenburg VT, Rachowicz LJ, Knapp RA, Stice MJ, Tunstall T, et al. Population genetics of the frog-killing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13845–50. 10.1073/pnas.0701838104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidd SE, Hagen F, Tscharke RL, Huynh M, Bartlett KH, Fyfe M, et al. A rare genotype of Cryptococcus gattii caused the cryptococcosis outbreak on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17258–63. 10.1073/pnas.0402981101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halkett F, Simon J-C, Balloux F. Tackling the population genetics of clonal and partially clonal organisms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:194–201. 10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Maximum-parsimony trees figures and Multiple alignments of 8 target gene fragments figure.