Abstract

Objectives

To investigate provider opinions about responsibility for medication adherence and examine physician-patient interactions to illustrate how adherence discussions are initiated.

Design

Focus group discussions with healthcare providers and audiotaped outpatient office visits with a separate group of providers.

Settings

Focus group participants were recruited from multi-specialty practice groups in New Jersey and Washington, D.C. Outpatient office visits were conducted in primary care offices in Northern California.

Participants

Twenty-two healthcare providers participated in focus group discussions. One hundred patients aged 65 and older and 28 primary care physicians had their visits audiotaped.

Measurements

Inductive content analysis of focus groups and audiotaped encounters.

Results

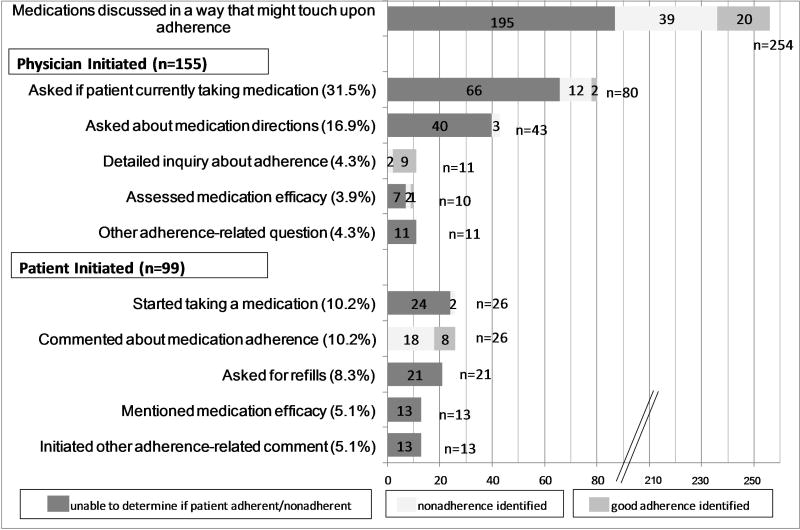

Focus group analyses indicated that providers feel responsible for assessing medication adherence during office visits and for addressing mutable factors underlying nonadherence. However, they believed that patients are ultimately responsible for taking medications and voiced reluctance about confronting patients about nonadherence. The 100 patients participating in audio taped encounters were taking a total of 410 medications. Of these, 254 (62%) were discussed in a way that might touch upon adherence; physicians made simple inquiries about current patient medication use for 31.5%, but they made in-depth inquiries about adherence for only 4.3%. Of 39 identified instances of nonadherence, patients spontaneously disclosed 51%.

Conclusion

The lack of intrusive questions about medication taking during actual office visits may reflect poor provider recognition of the questions needed to fully assess adherence. Alternatively, provider beliefs about patient responsibility for adherence may hinder detailed queries. A paradigm of joint provider-patient responsibility may be needed to better guide discussions about medication adherence.

Keywords: medication adherence, patient-physician relationship, provider-patient communication, prescription medication

INTRODUCTION

Poor medication adherence plagues medical care, affecting up to 40% of older adults in the United States.1 Nonadherence costs the United States healthcare system up to $290 billion dollars a year,2 and is associated with poor clinical outcomes, increased hospitalizations, and greater mortality rates.3–6 Healthcare providers can readily address some of the factors associated with nonadherence, such as: cost-related nonadherence;7,8 discomfort from medication side effects;9 perceptions of poor medication efficacy;9 and issues related to medication dosing, frequency, or timing.10

Physicians are partially held responsible for successful patient medication adherence—they may be financially rewarded or penalized by insurers based on how consistently their patients take their medications.11 Yet it is not clear whether physicians accept responsibility for patient medication adherence and whether they believe that they can affect adherence. These attitudes may affect whether and how physicians broach medication adherence during office visits.

Few studies have characterized how providers ask patients about medication adherence. Previous studies of hypertensive patients showed that providers assess adherence by directly asking whether patients are taking their medications,12,13 but often use linguistic approaches (e.g., closed-ended and declarative questions) that do not foster meaningful patient responses.13 Little is known about other approaches that providers actually use to gain insight into patient medication adherence or about patient contributions to these conversations. These approaches are important to understand because providers need to identify nonadherence before they can address it. Conversations assessing medication adherence may change as physicians obtain access to automated pharmacy information that will provide information about whether patients are appropriately filling their medications. Thus, it also is critical to understand physician views about detecting and addressing adherence.

The primary objectives of this paper are to: 1) use focus group discussions to explore provider opinions about responsibility for medication adherence and 2) analyze audio taped outpatient encounters between a separate group of physicians and their older patients to illustrate how physicians and patients initiate adherence discussions. These two analyses were juxtaposed to understand how provider attitudes concerning responsibility for adherence link with the content of provider-patient conversations about medication adherence.

METHODS

Focus group discussions

To assess physician opinions about their responsibility for patient medication adherence, we analyzed three focus groups conducted in 2006. The original purpose of the focus groups was to assess the acceptability and potential value of presenting prescribers with information about patients’ adherence to a medication therapy regimen in the context of electronic prescribing. Because of this, participants were recruited from multi-specialty private practice groups that were using the Allscripts Touchworks electronic health record (EHR) system.

Focus group participants were asked about their strategies to determine patient adherence to prescribed medications, and the extent to which they believed patient adherence was their responsibility. They also were asked to evaluate hypothetical EHR screens depicting the ability to flag patients with inappropriate refill patterns. All focus groups were audio taped and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The study protocol was approved by the UCLA and RAND institutional review boards.

Two investigators (DMT, TJM) employed inductive content analysis14,15 to iteratively analyze transcripts and identify themes related to: 1) how providers say they determine patient medication adherence; 2) provider opinions about responsibility for medication adherence; and 3) provider comfort with initiating discussions about adherence during versus outside of office visits. Themes were shared with the entire group of investigators, and then mutually agreed-upon coding categories were applied to all of the transcripts.16

Audio recorded physician-patient interactions

Data for this analysis were drawn from physician-patient encounters collected for the Physician-Patient Communication Project, conducted in Sacramento, CA in 1999. Full study methods are described elsewhere.17 Participants included 28 primary care physicians who practiced either in a group health maintenance organization setting or an academically-affiliated primary care network. Patients were recruited prior to scheduled office visits and had to speak English and have a new, worsening, or uncontrolled medical problem. In the original study, 909 patients were enrolled (68% of eligible patients approached), of which 632 visits were successfully audio recorded and transcribed. The data contained 100 encounters with patients aged 65 and older who were taking at least one medication for a chronic condition.18 We chose to investigate discussions with these patients because up to 40% of older patients are nonadherent to their medications.1.

The unit of analysis was a chronic medication. The total number of chronic medications was determined by comparing physician reports about the number of continued medications (collected immediately after the office visit) with the number of medications mentioned during the office visit.18 Investigators did not analyze conversations about vitamins, herbal supplements, medications for acute self-limited conditions, and those taken on an as needed basis, since adherence is difficult to quantify in these situations.

For each chronic medication, two of three investigators (DMT, TJM, NSW) applied codes to describe physician questions or patient comments that might touch upon or suggest medication adherence. Codes were based on previous literature,18–20 clinical experience, and findings from the focus groups analyzed for this study.

For each medication, the investigators assigned the codes in a mutually exclusive manner, such that the most detailed level of questioning was tabulated. Queries and statements concerning multiple medications (e.g., “Are you taking all of these?”) were assigned to all pertinent medications. The investigators also noted whether conversations revealed medication adherence (taking a prescribed medication exactly as recommended by the provider) or nonadherence (e.g., missed or skipped doses). They also distinguished between open- and closed-ended physician queries. Kappa coefficients were between 0.74 – 0.97. Discrepancies in coding were resolved by consensus among the three investigators.

RESULTS

Focus Group Discussions

Providers uniformly expressed that it was their responsibility to discuss medication adherence with patients. But they mostly reported asking general questions about a patient’s medication regimen (to assess whether patients were currently taking a medication), rather than direct questions about difficulties with medication-taking or missed doses.

How providers say they determine medication adherence

Providers said they used both verbal and observational strategies to assess patient medication adherence. Verbal strategies included asking general questions about medication taking, questions to reconcile patient medications, and direct questions about medication adherence. Observational strategies utilized reviews of patient medication bottles and medical records.

Almost universally, providers said they screen for non-adherence by asking patients general questions about their medication taking, or questions to reconcile patient medications. However, one provider noted the limitations of this approach: “You always ask them, ‘Are you taking your medicine?’ And they say, ‘Oh, yes.’” Another participant commented about how question wording can affect patient response: “… the best way to find out how well they’re adhering is not to say, ‘Are you on this? … but to ask them, ‘What are you taking?’” Some said they asked patients about dosing frequency, “… to see if they know which ones are twice a day, which ones are once a day.” One participant said she asks if patients are “tolerating these medications okay.” Only a few providers advocated more direct approaches to questioning patients, for example: “I ask bluntly; are you taking your medications every day?” or “Do you ever skip a dose or two?”

Providers less frequently mentioned observational strategies for assessing nonadherence. These approaches included: 1) asking patients to bring their medication bottles to office visits to look for discrepancies in medication regimens; 2) noting the frequency of medication refill requests (too frequent or too far apart); and 3) reviewing pharmacy benefit manager alerts about nonadherence (though participants noted that the reports were often untimely or inaccurate). Providers also said they considered the possibility of nonadherence when patients had uncontrolled medical conditions or did not make follow-up appointments.

Whose responsibility is medication adherence?

Participants felt strongly that providers have a professional responsibility to discuss adherence during office visits and to provide medication-related patient education. Specifically, they noted that providers should assess reasons for nonadherence, such as medication cost, unacceptable side effects, or dosing frequency, and help patients develop acceptable medication regimens. Some believed that providers should routinely ask patients about adherence, and many noted that certain medication classes require more frequent assessments.

Providers perceived a responsibility to address nonadherence once they were aware of it, regardless of the information source (e.g., discussions with patients, pharmacy benefit manager reports). As one participant noted, “… once I have information, I feel I have to follow-up on it.” However, there was a great deal of concern about not having enough time or resources to address nonadherence if the patient was not physically in the office. Concerns about practicality became compelling when participants discussed the possibility of receiving computer-generated reports and alerts. Several providers said they preferred not to receive notices about potential nonadherence because it was too much information for them to deal with outside the context of an office visit.

Though participants felt they should talk to their patients about nonadherence, they uniformly noted that the final responsibility for taking the medication fell to the patient: “I just feel that, at some point, my responsibility for educating a person and giving them the proper treatment ends, and their personal responsibility begins …” There was extensive discussion about the legal ramifications of not addressing nonadherence once the provider became aware of it. Participants were concerned that nonadherent patients might blame providers for not providing enough information about their medications. The following exchange exemplified provider frustration about being held responsible for patient adherence:

Participant 1: I think that this boils down to, it’s the patient’s prerogative to choose whether they follow your advice or not.

Participant 2 (pretending to be a patient): But Doctor, the next day I didn’t understand the consequences if I didn’t [take the medication]. That wasn’t made clear to me.

Participant 1: [jokingly] The next lawyer stands up [in court during a lawsuit].

Participant 3: You know what’s interesting is that patients don’t want this paternalistic or maternalistic physician where they say, “Do as I say.” They want to be part of the decision-making, yet these type of systems almost drive a paternalistic approach which is, “I caught you, you didn’t take your medicine.” … I want to offer you my knowledge, my advice, but I don’t want to be your babysitter … You decide you want to be non-compliant. You’re purposefully doing that, you made a bad choice. Don’t blame it on me.

Comfort with initiating discussions: during versus outside an office visit

In general, providers said they felt more comfortable talking about nonadherence during face-to-face meetings with patients, rather than outside of office visits. One participant said: “… you’re sitting with them in the office, going over their pills at their visit … You can say, ‘Oh, you know what? While I’m refilling your pills, I noticed that you didn’t refill the Lisinopril I prescribed six months ago. What’s going on with that?’ That seems to be more collaborative … as opposed to confrontational.” Many participants worried that it would be intrusive to contact patients outside of office visits about suspected nonadherence unless patients knew in advance that providers had access to pharmacy data. Several said that patients might think they were being followed by “Big Brother,” who was monitoring their every move.

Multiple participants in each focus group said they felt uncomfortable about making unsolicited phone calls to question patients about medication adherence. Despite wariness about receiving electronic alerts about patient nonadherence, providers were interested in accessing information about patient refill patterns, on an “as needed” basis.

Audio recorded physician-patient encounters

The second part of the study analyzed 100 actual physician-patient encounters. Patients had a mean age of 73.6 years (SD=5.9, range 65–89), 93% were Caucasian, 67% had at least some college education, and 97% had health insurance. They had a mean of 2.1 co-morbidities (SD=1.4, range 0–7), and were taking a total of 410 medications and dietary supplements,18 for which information related to adherence was touched on for 254 medications (62%) during 86 visits.

Figure 1 lists the codes corresponding to physician questions or patient comments that might touch upon or suggest medication adherence, and notes the number of medications for which each query or comment was made. It also illustrates whether each discussion resulted in identification of patient adherence or nonadherence.

Figure 1.

Physician and patient-initiated questions and comments concerning adherence (n=254 medications); total medications discussed was 410.

Physician initiated discussions

Codes used to describe physician questions that might touch upon adherence included: whether patients were currently taking a medication, medication directions / dosing, detailed questions about medication adherence (e.g., whether the patient had ever missed or skipped a medication), medication efficacy, and other adherence-related topics (e.g., questions about affordability and side effects).

Providers most often touched upon medication adherence discussions by asking questions about whether patients were currently taking medications; this was completed for 80 of 254 (31.5%) of the medications discussed during the visits (and 19.5% of medications overall). These questions were often framed by listing medications and asking if patients were taking them, or by asking patients what medications they were taking. For 16.9% of discussed medications, physicians made more detailed queries about the patient’s pattern of medication use: medication dose, number of tablets, frequency of use, or time of day taken.

Detailed inquiries touching on adherence were made by 7 different physicians for 11 medications (4.3% of discussed medications and 2.6% of medications overall). Most of these inquiries led to patients affirming that they were adherent, but the questions were phrased in a closed-ended fashion likely to elicit a socially desirable response. For example, one provider asked, “You’re taking all your medicines, right?” and another queried “Now you do take it every night, right?” Inquiries such as: “Are you using it daily, regularly?” and “Do you take your meds … frequently, throughout the day?” elicited more substantive responses from patients. In response to the first question, the patient said, “everyday, two squirts,” and the reply to the second was “… that’s one thing I’m faithful with, is my medicine. I always take it.” Ninety percent of provider questions were phrased as closed-ended, rather than open-ended questions.

Patient initiated discussions

Patients voluntarily initiated over one-third of the adherence-related discussions observed in the study. Codes corresponding to unsolicited patient comments that might touch upon adherence included: statements about taking a medication, specific comment about medication adherence, refill requests, medication efficacy, and other comments related to adherence (e.g., concerns about medication cost or side effects). For 26 of the 254 medications assessed (10.2%), patients commented explicitly about medication adherence—mentioned taking the medication as recommended, having difficulty with the medication, or strategies they used to enhance medication-taking.

Identification of medication nonadherence

Nonadherence was identified for 19 of the 155 medications (12%) for which physicians initiated questions that might touch upon adherence; for 31 medications (20%) the discussions revealed good adherence; and for another 105 medications (68%) there was no indication about whether the patient was taking the medication as prescribed. Physicians identified 12 instances of nonadherence by asking whether a patient was taking a certain medication. Of these, 6 patients had stopped or were not currently taking a medication and another 6 disclosed that they were not taking a medication exactly as recommended. Patient comments were instrumental in helping physicians to identify nonadherence. Overall, 39 instances of nonadherence were identified in 32 of 100 visits; 20 of these were identified from patient-initiated comments. During two visits, patient descriptions of their medication regimens alerted physicians to the fact that their regimens differed from the physician’s recommendations.

We classified the reasons identified for patient nonadherence into several broad themes: 1) intentional nonadherence (e.g., poor understanding about medication purpose or proper use; fear of perceived or experienced side effects, self-decision to increase dose); 2) unintentional (e.g., forgot to take medication, accidentally took extra dose, misunderstanding about dosing, regimen, or how long to take medication); 3) organizational (e.g., non-cost related problem with prescription at pharmacy, did not have refills, cost); and 4) unknown because not explored during visit. Most instances of patient nonadherence were unintentional or intentional knowledge-based.

Provider responses to detected nonadherence

Physicians almost always addressed nonadherence when it was discovered. To address unintentional nonadherence, providers educated patients about proper dosing or timing of medication intake, reinforced the need for ongoing medication use, and provided concrete suggestions about reminder systems for medication-taking. In response to intentional nonadherence, they explored the cause of non-adherence in order to offer a targeted response: educating patients about the purpose of taking a medication or about appropriate dosing, and changing or adjusting medications for patients experiencing unwanted side effects. In a few instances, providers affirmed patients’ independent decisions to increase medication dosing. Organizational adherence issues were addressed by refilling prescriptions, and for one patient in the study with cost-related nonadherence issues, by changing medications to more affordable ones. Often a combination of strategies was employed. Patient comments about nonadherence were addressed in all but 3 visits.

Table 1 illustrates several conversations in which nonadherence was identified and addressed. These represent the best depictions of adherence discussions in the data. Example 1 illustrates how substantive patient responses to simple physician questions can lead to productive conversation about medication taking (lines 1–4 and 17–18). Example 2 depicts a patient-centered approach in which the physician and patient worked together to develop a mutually acceptable solution concerning the patient’s medication regimen.

Table 1.

Examples of Actual Physician-Patient Interactions about Nonadherence

| Example 1. | |

| DOCTOR: | Are you still taking your Prilosec? |

| PATIENT: | I am. Two in the evening. Right now I am only taking two in the evening because Dr. X put me on tetracycline, 50 tablets. I have … 25 more, so I cut the Prilosec in the morning … |

| DOCTOR: | You only take two at night. |

| PATIENT: | Umm hmm. |

| DOCTOR: | Are you getting heartburn? |

| PATIENT: | Yes I do. |

| DOCTOR: | You are still getting heartburn. Why can’t you take your Prilosec in the morning too? |

| PATIENT: | Because I am on tetracycline. |

| DOCTOR: | So what? |

| PATIENT: | Because the antacids. … |

| DOCTOR: | It is not an antacid. Prilosec is not an antacid. Maalox is an antacid. Prilosec is a drug that turns off the acid … after your breakfast, take two Prilosec. |

| PATIENT: | Then I am going to two in the morning and two in the evening? |

| DOCTOR: | Umm hmm. Two in the morning and two in the evening. (intervening conversation) |

| DOCTOR: | You are not on a diuretic are you? |

| PATIENT: | I am but I am forgetting to take it. I take it maybe once in three to four weeks. |

| DOCTOR: | What is it? |

| PATIENT: | Hydrochlorothiazide, or something. |

| DOCTOR: | Is it once in three weeks? |

| PATIENT: | Yeah, because I am forgetting because I don’t want … |

| DOCTOR: | Why don’t you put with your medicines? … You know, most of your medications you can take at once. |

| Example 2. | |

| DOCTOR: | OK. The only thing here is that your thyroid … it was a little bit high, this TSH level … and what that means is actually just the opposite, that your thyroid activity is slightly low … |

| PATIENT: | OK. Well I’m taking thyroid, then I wonder if we need to up the dose. |

| DOCTOR: | Right, we might need to increase cause last year I think yours was a little high like this, this is just barely high. But it was that way before and when we repeated it, it was normal. Now what, what sometimes happens is if you take the thyroid medicine ah, in a different relationship to food, sometimes it’ll be absorbed differently into your body. |

| PATIENT: | I take it every morning. |

| DOCTOR: | And you take it on an empty stomach? |

| PATIENT: | No, I take it with breakfast. |

| DOCTOR: | All right. It actually works better, it gets into your system better, if you take it on an empty stomach. |

| PATIENT: | Oh. |

| DOCTOR: | So one way to, to get more of that into your system would be to just take it on an empty stomach. The other thing is if you feel that you’re gonna continue taking it with food … is to raise the dose. |

| PATIENT: | OK. Because some of the other things I take have to be with food, … I’d rather do it with food. |

| DOCTOR: | But it’s important, the real important thing is to be consistent. |

| PATIENT: | Right. |

| DOCTOR: | Because if, if you sometimes take it with, with food, sometimes without food … then it kind of gets erratically absorbed and it’s harder to really adjust it. |

| PATIENT: | OK, well I have a little routine every morning, I take the Prozac, the diuretic, the Premarin, the thyroid, and the uh, U, let’s see, the Unifil, and the Voltaren. [Chuckles] And then at bedtime I take the, the others. So it would just, I mean, if I, if I try to say well gee I’m gonna take the thyroid first, the minute I get out of bed, you know it just isn’t practical, cause I forget. This way I usually can remember it. |

| DOCTOR: | Just trying to look up the dose here. Point zero seven five. |

| PATIENT: | It’s the gray cap, the tablets. |

| DOCTOR: | Yeah. Uh. That’s a fairly low dose so, what we might wanna do, the next step up would be zero point one. |

| PATIENT: | OK. |

| DOCTOR: | All right. So I’ll give you that. |

CONCLUSION

This study combines two different types of data collected from two different groups of healthcare providers practicing in different settings at different times. The results are not completely comparable, but the contrast between what providers believe and what they do is compelling. Only a minority of physicians asked patients detailed questions about medication adherence, though providers uniformly felt it was their responsibility to assess and address medication adherence. On a deeper level, providers indicated that they did not want to intrude into patients’ territory to detect nonadherence. In the office, they rarely challenged patients or delved into patient behaviors to reveal missed medication doses. More than half of non-adherence detected during office visits was voluntarily announced by unprovoked patient comments.

While providers often performed medication reconciliation (checked medications a patient is taking),18 they rarely explicitly assessed adherence on these reconciled medications. This suggests that providers may count on the reconciliation process to reveal non-adherence, and may reflect a lack of training about how to actively query patients about non-adherence. Trained staff or an automated system to reconcile patient medications might give providers more time to focus on patient-specific barriers to adherence, such as dosing schedule or motivational issues. However, the lack of in-depth adherence assessment may reflect providers’ limited perceived responsibility to probe or interrogate patients about adherence, as suggested by the providers in the focus groups who said that patients are the ones ultimately responsible for taking their medication.

Provider reluctance to be intrusive or overbearing has important implications for the vast array of new information that is becoming available from pharmacy benefit plans, managed care plans and other data repositories. Simple verification of a patient’s medication regimen is quite different than the types of interactions that should be prompted by data demonstrating unfilled prescriptions and missed refills. Further work is needed to understand how providers and patients feel that information about nonadherence should be handled because it will require an approach different than found in the current study. It also should be noted that the restricted scope of responsibility and intrusiveness described by the physicians contrasts starkly with the comprehensive care perspective envisioned by the medical home.

There may be other reasons that providers rarely queried directly about skipped doses or difficulty with medication cost. Some might hypothesize that this is due to time pressure during outpatient office visits,21 or that discussions may vary based on patient complexity. However, providers participating in the focus groups did not pinpoint these issues as barriers during face-to-face discussions. Another explanation may be that providers do not believe more detailed questions are warranted unless they suspect that patients are nonadherent. Previous studies have shown that providers infrequently discuss cost-related nonadherence,7,22 often because of concerns about patient discomfort, lack of habit, or insufficient time.22,23 However, research suggests that physicians cannot accurately identify patients with difficulty affording their medications,24 and often do not query nonadherent patients about their medication use.13

Patient contributions are invaluable to physician-patient discussions about medications, and patient comments can greatly influence physician behaviors.17 Focus group participants rarely mentioned patient-initiated comments as a means to discovering nonadherence, but in the interactions examined, patients voluntarily offered over half of the statements identifying nonadherence. Patient participation in these discussions is important because patients who actively participate in their medical encounter are more adherent to treatment recommendations25 and have better health outcomes.26–28

The study results suggest that both provider- and patient-targeted interventions could increase provider identification of medication nonadherence. Providers could be trained to recognize that simple medication reconciliation does not capture all forms of medication nonadherence, and that they should ask more direct questions about patient difficulties with medication-taking. A multitude of social and behavioral factors have been linked to medication adherence.29–31 Thus providers could systematically assess the reason(s) behind a patient’s nonadherence in order to target solutions. Patient-targeted interventions could encourage patients to bring accurate medication lists to their visits so that providers can conduct medication reconciliation (and capture unintentional nonadherence). Interventions also could promote patient activation about problems with medication taking.

The study findings are limited by the age of the data, discordance of the time frames in which they were collected, and the small number of providers participating in the study. In addition, each of the two types of data collected in this study pose limitations. Audio taping of office visits may have altered participant behavior (Hawthorne effect).32 However, the range of discussions seen was consistent with behaviors reported by providers during focus group discussions. In addition, the study’s original focus was not specific to medications, making it unlikely that participants altered their behavior when discussing medications. Participants observed during office visits were mostly Caucasian, all aged 65 and older, and located in a single geographical region. They spoke English, most had at least some college education, and almost all had health insurance. These data may not be generalizable to vulnerable patient populations. Audio-recordings were collected in 1999; the content of current physician-patient discussions may differ due to the advent of electronic medical records or evolving healthcare practices. However, the discussions observed were consistent with what providers in the focus groups (conducted in 2006) reported. No objective measure of patient adherence was available to identify the level of sensitivity of conversations.

The focus group format chosen to assess provider perspectives about adherence also is subject to several limitations. Participants were all from practices using the Allscripts EHR, so their experiences and practice may differ from those without e-prescribing programs. In addition, participants all were recruited from small to medium-sized independent practices on the East coast, and their opinions may differ from those of providers in other parts of the country. Patients were not included in the focus groups. Their views on responsibility for adherence should be explored.

These findings demonstrate a gap between clinician views and behaviors and the emerging potential to enhance medication adherence in the electronic age. While these findings raise more questions than they answer, they identify a need to better define how providers and patients believe that adherence information should be used and to develop more effective methods for providers and patients to interact in order to identify medication nonadherence and then enhance adherence behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Some of the data used in this study were collected with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant #034384) and by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant # 1U18HS016391). Dr. Tarn was supported by a UCLA Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award (5K12AG001004) and by the UCLA Older Americans Independence Center (NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG028748).

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis and preparation of the paper. The manuscript content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Derjung M. Tarn and Neil S. Wenger: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation. Douglas Bell and Richard L Kravitz: acquisition of subjects and data, manuscript preparation. Thomas J. Mattimore: data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation.

Paper Presentations: The study was presented at the North American Primary Care Research Meeting (NAPCRG).

References

- 1.Wilson IB, Schoen C, Neuman P, et al. Physician-patient communication about prescription medication nonadherence: A 50-state study of America's seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:6–12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooney E. Study urges action to get patients to follow prescriptions. [Accessed January 25, 2012];Boston Globe. 2009 Aug 14; Available at: http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2009/08/14/study_urges_action_to_get_patients_to_follow_prescriptions/

- 3.McDermott MM, Schmitt B, Wallner E. Impact of medication nonadherence on coronary heart disease outcomes. A critical review. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1921–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberopoulos EN, Florentin M, Mikhailidis DP, et al. Compliance with lipid-lowering therapy and its impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:717–725. doi: 10.1517/14740330802396984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Calverley P, et al. Adherence to inhaled therapy, mortality, and hospital admission in COPD. Thorax. 2009;64:939–943. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.113662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallagher EJ, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI. The relationship of treatment adherence to the risk of death after myocardial infarction in women. JAMA. 1993;270:742–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290:953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng CW, Brook RH, Keeler E, et al. Cost-lowering strategies used by medicare beneficiaries who exceed drug benefit caps and have a gap in drug coverage. JAMA. 2004;292:952–960. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, et al. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: Findings from a 2003 national survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-152–W5-166. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:e22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed January 25, 2012];HEDIS measures. 2009 Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/784/Default.aspx.

- 12.Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Physician counseling for hypertension: What do doctors really do? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bokhour BG, Berlowitz DR, Long JA, et al. How do providers assess antihypertensive medication adherence in medical encounters? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babbie ER. The basics of social research. 5. Australia ; Belmont, CA: Wadsworth / Cengage Learning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Azari R, et al. Direct observation of requests for clinical services in office practice: What do patients want and do they get it? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1673–1681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Kravitz RL, et al. How do physicians conduct medication reviews? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1296–1302. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, et al. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Heritage J, et al. Physician communication about the cost and acquisition of newly prescribed medications. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mechanic D. How should hamsters run? Some observations about sufficient patient time in primary care. BMJ. 2001;323:266–268. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Tseng CW, et al. Barriers to patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:856–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Physician strategies to reduce patients’ out-of- pocket prescription costs. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:633–636. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heisler M, Wagner TH, Piette JD. Clinician identification of chronically ill patients who have problems paying for prescription medications. Am J Med. 2004;116:753–758. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–675. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27:S110–127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr, et al. Patients’ participation in medical care: Effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray MD, Morrow DG, Weiner M, et al. A conceptual framework to study medication adherence in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s1543-5946(04)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill MN, Miller NH, Degeest S, et al. Adherence and persistence with taking medication to control high blood pressure. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franke R, Kaul J. The Hawthorne experiments: First statistical interpretation. Am Sociological Rev. 1978;43:623–643. [Google Scholar]