Abstract

The diagnosis of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) can be challenging, particularly given recent advances in NBIA genetics and clinical nosology. Although atypical cases continue to challenge physicians, by considering clinical features along with relevant neuroimaging findings, the diagnosis of NBIA can be made confidently. In addition, the identification of genetically-distinct forms of NBIA allows clinicians to better provide prognostic and family counseling services to families, and may have relevance in the near future as clinical trials become available. We describe a heuristic approach to NBIA diagnosis, identify important differential considerations, and demonstrate important neuroimaging features to aid in the diagnosis.

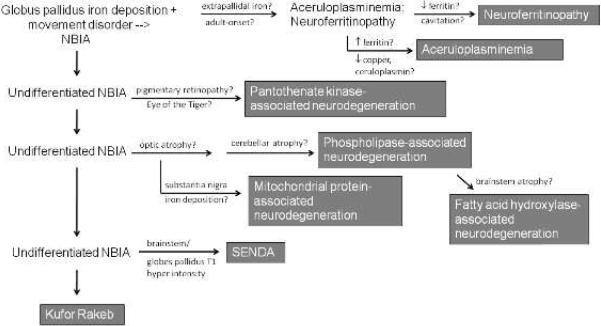

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation characterizes a class of progressive neurological disorders that feature prominent extrapyramidal symptoms, intellectual impairment, and iron deposition on MRI. Seven disorders have currently been identified as subtypes of NBIA. There is considerable phenotypic heterogeneity among the NBIA disorders, making the diagnosis of these rare diseases challenging. However, by combining clinical and neuroimaging features, the consulting physician may confirm that an affected individual has an NBIA disorder, and correctly characterize the subtype of NBIA (Figure 1). This, in turn, informs family counseling, guides prognostic and treatment decisions, and may have relevance for future clinical trials.

Figure 1.

Clinical and radiographic approach to NBIA

The age of onset of NBIA disorders may vary greatly depending upon the nature of the underlying mutation. This is illustrated by the case of mutations in PLA2G6, which may cause a rapidly progressive infantile neurodegenerative disease (infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy) or a slowly progressive movement disorder with onset in adulthood (Paisan-Ruiz, et al. 2009). However, some generalities can be made about age of onset, particularly in regard to classically adult-onset disease.

Initial clues

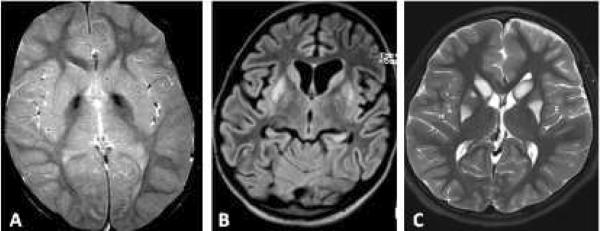

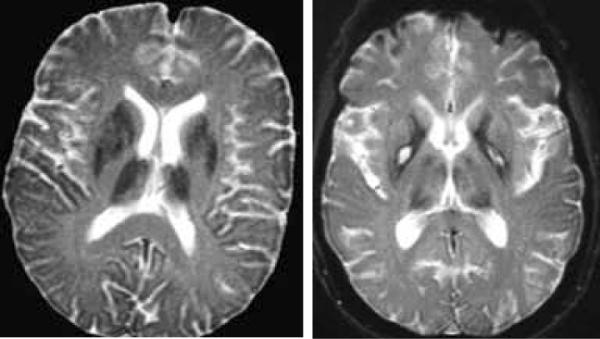

The diagnosis of NBIA is typically suspected once compatible MRI features are identified in the context of a progressive movement disorder, typically but not universally extrapyramidal. An important initial distinction between NBIA and other conditions that lead to both extrapyramidal findings and abnormal basal ganglia signal is the nature of the T2 signal. NBIA disorders produce a characteristic hypointensity of the basal ganglia, while other disorders, such as mitochondrial encephalopathies, organic acidurias, and abnormalities of cofactor metabolism, feature T2 hyperintensity (Figure 2). Furthermore, NBIA typically leads to a symmetric, homogeneous hypointensity, in contrast to the pattern seen with extravasated blood products.

Figure 2. Contrast between disorders of iron deposition and disorders of energy production.

Idiopathic NBIA (A): iron deposition disorders feature a characteristic hypointensity of the basal ganglia, most typically the globus pallidus. Mitochondrial encephalopathy with complex I deficiency (B&C): mitochondrial disorders, in contrast, often feature basal ganglia T2 hyperintensity.

Differential considerations

Lysosomal storage disorders (Autti, et al. 2007) may also be associated with T2 hypointensity, putatively due to the intrinsic signal of accumulated storage material, and may also feature a progressive, degenerative course and/or dystonia-parkinsonism. Pragmatically, once T2 hypointensity is identified, gradient echo (T2*) and susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences should be reviewed. These sequences help distinguish iron deposition from other forms of T2 hypointensity. Furthermore, iron deposition typically also appears hypointense on both DWI and ADC sequences, which can further confirm the diagnosis.

Friedreich's ataxia may feature selective iron accumulation in the dentate nucleus (Waldvogel, et al. 1999), but is not typically considered among the NBIA disorders as there is no involvement of the basal ganglia and extrapyramidal symptoms are typically absent. The iron deposition in Friedreich ataxia may not be readily appreciable without analysis of R2* values. Friedreich ataxia may feature optic neuropathy (Fortuna, et al. 2009) and the dentate iron deposition may be ameliorated with deferiprone treatment (Boddaert, et al. 2007).

Hypomyelinating leukoencephalopathies, such as Pelizaeus-Merzbacher, may feature hypointense-appearing basal ganglia. However, although several NBIA disorders may feature white matter hyperintensity, the lack of normal myelination that occurs in hypomyelinating disease should lead the clinician away from a diagnosis of NBIA.

In addition to NBIA, iron deposition in the basal ganglia may occur in cases of multiple sclerosis and related inflammatory disorders of the central nervous system, although typically this finding is not associated with clinical symptoms of basal ganglia dysfunction. Other neurodegenerative disorders to be considered that may include basal ganglia iron deposition include HIV dementia (Miszkiel, et al. 1997) and Huntington disease (Bartzokis, et al. 1999) as well as more classically adult-onset sporadic forms of neurodegenerative disease, including multiple system atrophy (Strecker, et al. 2007) and corticobasal degeneration (Molinuevo, et al. 1999).

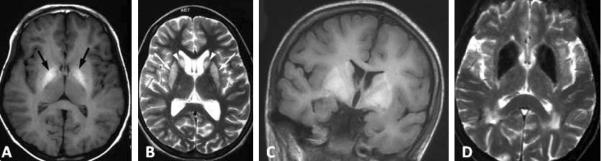

Other metal accumulation disorders

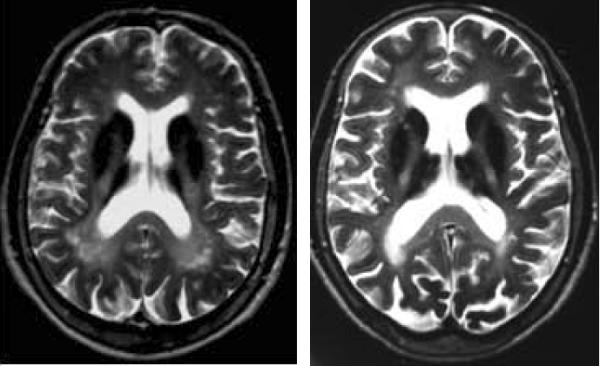

Wilson disease can also be associated with T2 hypointensity of the deep gray nuclei, although typically the signal change associated with Wilson's is more heterogeneous and may feature prominent concurrent hyperintensities. Calcium can also produce T2 hypointensity. In ambiguous cases, CT may be of great use in distinguishing calcium (hyperdense) from iron (isodense). Symmetric deposition of calcium may occur in inherited calcinoses (Fahr disease) or in hyper- or hypoparathyroidism and can be associated with extrapyramidal findings on examination. Finally, an inherited disorder of manganese accumulation has just recently been described (Tuschl, et al 2012; Quadri, et al. 2012). This disorder leads to T1 hyperintensity of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus, similar to the pattern seen in environmental manganism. Examples of metal deposition disorders are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. MRI appearance of metal deposition disorders.

(A&B) Wilson disease; (C) inherited hypermanganism caused by SLC30A10 mutation; (D) Fahr disease. Images reprinted by permission

A stepwise approach to diagnosis

It is important to recognize that in ~40% of patients with clinical and radiologic features of NBIA, despite adequate genetic workup, an etiology cannot be identified (Hartig, et al. 2011; Panteghini, et al. 2012). Thus a substantial proportion of patients may still be considered to have idiopathic NBIA. Despite this finding, for the majority of patients, a diagnosis can be made. We present here a heuristic approach to the diagnosis guided by clinical and imaging features.

Overview

Clinical features in NBIA may include intellectual decline, dystonia, parkinsonism, ataxia, spasticity, and neuropsychiatric features. However, these findings may be highly variable, even between patients with the same subtype of the disorder. For this reason, MRI features may be particularly instructive. Some of the observed variation may be related to the form of underlying mutation (i.e. missense vs. loss of function) (Engel, et al. 2010).

After iron deposition is identified on the MRI, the pattern of iron accumulation should be evaluated. In particular the involvement of sites outside of the globus pallidus is important for diagnosis. Dilated funduscopic exam may be helpful in identifying coexisting pigmentary retinopathy or optic atrophy, and visual evoked potentials may be useful in identifying subclinical retinal degeneration or optic neuropathy. Potentially useful screening tests include a CBC with peripheral smear (ideally diluted 1:1 with normal saline before evaluation), copper, ceruloplasmin, and serum iron indices.

I. Extrapallidal lesions

Neuroferritinopathy

Neuroradiologic findings in neuroferritinopathy

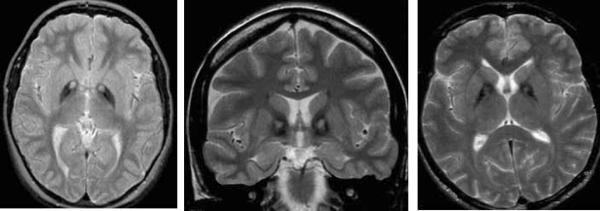

In neuroferritinopathy, patchy T2 hypointensity of the caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, putamen, thalamus and dentate nuclei occurs. Over time, T2 hyperintense lesions may evolve and lead to a cavitary appearance (Figure 4). Mild cerebral and cerebellar atrophy may also develop.

Figure 4.

Neuroferritinopathy

Laboratory abnormalities in neuroferritinopathy

Deposits of iron can be seen in muscle or nerve biopsy (Schroder 2005). Helpful screening tests include serum ferritin levels, which are frequently decreased (Chinnery, et al. 2007).

Clinical features of neuroferritinopathy

Neuroferritinopathy typically presents in adulthood, and is rare outside of founder populations in the UK and France (Chinnery, et al. 2003). Extrapyramidal features may be complex, combining parkinsonism, choreoathetosis, dystonia, tremor, and ataxia. Frontal lobe or subcortical dementia is often noted subsequent to motor symptoms, and autonomic features may be observed. A supranuclear gaze palsy develops in some cases. The lack of associated ophthalmologic features can be helpful in distinguishing neuroferritinopathy from other forms of NBIA.

Aceruloplaminemia

Neuroradiologic findings in aceruloplasminemia

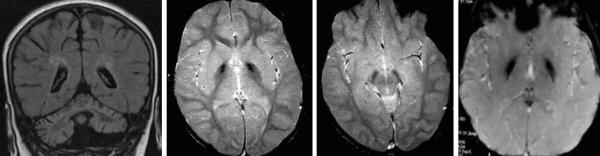

In aceruloplasminemia, more homogeneous lesions of the caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, thalamus, red nucleus, and dentate occur with concurrent white matter hyperintensities (Figure 5). Cerebellar atrophy may be seen in some cases.

Figure 5.

Aceruloplasminemia

Laboratory abnormalities in aceruloplasminemia

Screening labs can be helpful in diagnosing ACP, as ceruloplasmin and copper are often low or undetectable, and decreased serum iron, microcytic hypochromic anemia, and elevated ferritin often occur (Miyajima, et al. 2003).

Clinical features of aceruloplasminemia

Clinically, affected patients present with blepharospasm, chorea, craniofacial dyskinesias, ataxia, and retinal degeneration. Aceruloplasminemia is the only form of NBIA that features prominent signs of peripheral organ involvement, with diabetes and liver diseases often observed.

Most forms of NBIA present with predominant involvement of the globus pallidus. This differential includes pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), phospholipase-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN), fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration (FAHN), the recently identified mitochondrial protein associated neurodegeneration (MPAN), and Kufor Rakeb syndrome (KRS). Static encephalopathy with neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA) syndrome also falls into this category, but is readily distinguished by atypical features.

II. Ophthalmologic features

The absence of ophthalmologic findings does not exclude any single form of NBIA. However, the presence of pigmentary retinopathy is strongly suggestive of PKAN, and is not seen in other forms of NBIA. In contrast, optic atrophy can be seen in phospholipase-associated neurodegeneration, fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration, and mitochondrial protein-associated neurodegeneration. No funduscopic abnormalities have been described in Kufor Rakeb syndrome or SENDA.

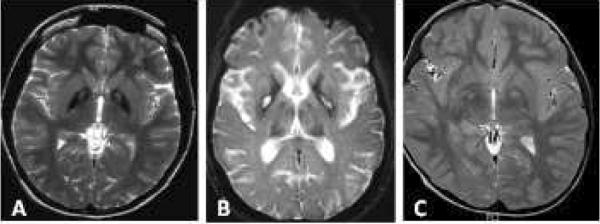

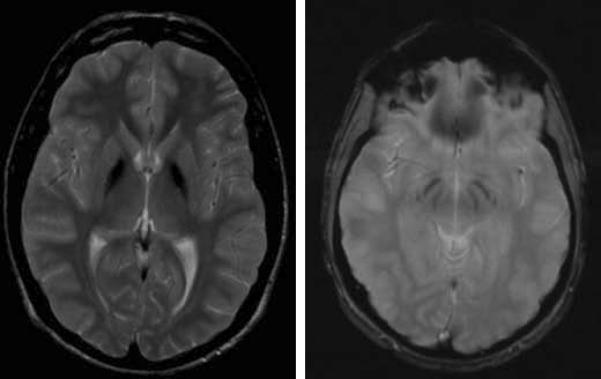

III. The eye of the tiger sign

The first assessment in differentiating forms of pallidal NBIA should be to determine whether an `eye of the tiger' is present. This radiologic sign is evident on axial T2-weighted images as a bilateral central hyperintensity within the otherwise hypointense globus pallidus. The eye of the tiger is highly sensitive and specific for pantothenate-kinase associated neurodegeneration, and can even be seen in presymptomatic affected individuals (Hayflick, et al. 2001). The central pallidal hyperintensity can fade as the disease progresses, leading to “eye of the tiger-negative PKAN.” However, the identification of this sign should prompt a high index of suspicion for PKAN. Cases of other neurodegenerative syndromes (i.e. multiple system atrophy, neuroferritinopathy) with purported eye of the tiger signs are often atypical in appearance and careful assessment often reveals irregular contour and/or lateral displacement of the central hyperintensity (Figure 6). Cases of MPAN with purported eye of the tiger signs have been reported, but images have yet to be published. Other differential considerations include disorders that can be associated with pallidal hyperintensity, sometimes mimicking the “eye of the tiger,” including neurofibromatosis, multiple sclerosis, and even Machado-Joseph Disease (spinocerebellar ataxia type 3). However, a key clue in this context is the lack of surrounding hypointensity; in general, without iron, one cannot reliably diagnose NBIA based on neuroimaging features.

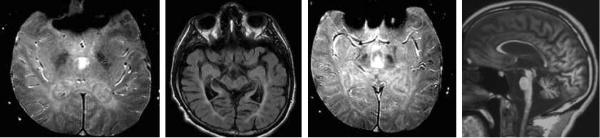

Figure 6. Eye of the tiger in PKAN and mimics.

(A) Eye of the tiger in PKAN; (B) Eye of the tiger-like appearance in neuroferritinopathy; (C) Neurofibromatosis; note lack of surrounding hypointensity that would indicate iron deposition.

Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN)

Neuroradiologic findings in PKAN

In PKAN, the brain is typically remarkably unaffected outside of the globus pallidus (Figure 7). Neuropathologically, there is mild involvement of the substantia nigra, which may or may not be reflected on MRI.

Figure 7.

PKAN

Laboratory abnormalities in PKAN

The detection of acanthocytes on peripheral blood smear supports a diagnosis of PKAN. Although not performed routinely, detailed lipoprotein analysis may demonstrate deficiency of the pre-beta fraction (Houlden, et al. 2003).

Clinical features of PKAN

Clinically, patients may present after an intercurrent illness, and stepwise declines are seen in some patients as well. affected patients present with generalized dystonia with particularly prominent oro-bucco-lingual dystonia. In some cases, this can lead to mutilatory tongue-biting. In others, this can be associated with task-specific forms of eating dystonia. The generalized dystonia in PKAN can be quite severe, leading to status dystonicus with rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in extreme cases.

IV. Peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy can occur in both phospholipase-associated neurodegeneration and mitochondrial protein-associated neurodegeneration. In MPAN, this tends to be a motor axonal neuropathy, and occurs in approximately 40% of cases (Hartig, et al. 2011). In PLAN, a mixed sensorimotor axonal neuropathy also occurs in around 40% of cases. Although less common, fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration may present similarly to both PLAN and MPAN, and may feature a sensory axonal neuropathy as well (Pierson, et al. 2011).

V. Neuroaxonal spheroids

Nerve biopsy (sural nerve, but also including skin, conjunctiva, muscle, areola, and rectal mucosa) may demonstrate neuroaxonal spheroids in >80% of cases with PLAN. Within this issue, Panteghini, et al. demonstrate the presence of neuroaxonal spheroids on skin biopsy in MPAN for the first time. Neuroaxonal spheroids have not been described in FAHN thus far, and it is unknown whether they occur in other forms of NBIA.

Outside of the founder population in Poland, PLAN seems to be more common than MPAN based on available incidence data, suggesting that it is reasonable to sequence PLA2G6 before sequencing C19orf12 for mutations.

Phospholipase-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN)

Neuroradiologic findings in PLAN

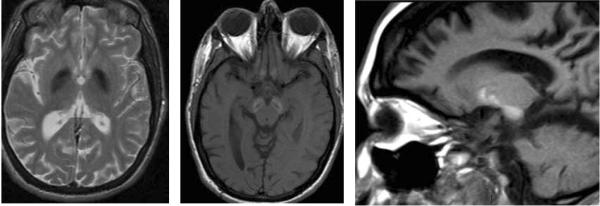

Progressive cerebellar atrophy with associated cerebellar T2 white matter hyperintensity is typical. Iron deposition in the globus pallidus and/or substantia nigra is seen in most patients, but this finding can follow symptom onset by several years. Symmetric subcortical T2 white matter hyperintensities can also be seen, with thinning of the corpus callosum (Figure 8). Patients presenting with dystonia-parkinsonism in adulthood may have only frontally-predominant white matter signal changes and mild cerebral atrophy, without cerebellar findings or iron deposition.

Figure 8.

PLAN

Laboratory abnormalities in PLAN

Outside of biopsy findings, no consistent laboratory abnormalities have been identified in patients with PLAN.

Clinical features of PLAN

Clinically, patients with phospholipase-associated neurodegeneration display significant phenotypic heterogeneity, with presentation in infancy associated with an infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy phenotype (global developmental delay/frank psychomotor regression with severe hypotonia). NBIA-associated phenotypes include dystonia, ataxia, and spasticity, with peripheral neuropathy, optic atrophy, and epilepsy in a minority of patients.

Mitochondrial protein-associated neurodegeneration (MPAN)

Neuroradiologic findings in MPAN

This recently described form of NBIA (Hartig, et al. 2011) features hypointensity of the globus pallidus and substantia nigra, with relative preservation of the remainder of the cortex, cerebellum and brainstem (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

MPAN

Laboratory abnormalities in MPAN

No consistent laboratory features have been identified in MPAN patients.

Clinical features of MPAN

Clinical findings include generalized dystonia, with a prominent orobuccolingual component. Parkinsonism is seen in about a third of patients. Pyramidal tract findings are frequent, and executive dysfunction and obsessive-compulsive behavior are seen in some patients.

VI. Brainstem and cerebellar atrophy

Progressive volume loss affecting both the brainstem and cerebellum may be seen in both fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration, and Kufor Rakeb syndrome. FAHN features subcortical T2 white matter hyperintensities, while KRS may feature prominent cerebral atrophy.

Fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration (FAHN)

Neuroradiologic findings in FAHN

MRI findings in FAHN may include thinning of the corpus callosum, brainstem and cerebellar atrophy, and confluent subcortical T2 white matter hyperintensities in addition to hypointensity of the globus pallidus (Figure 10). The hypointensity seen in FAHN has been noted to be more subtle than that seen in other forms of NBIA (Garone, et al. 2011).

Figure 10.

FAHN

Laboratory abnormalities in FAHN

PAS-positive granular inclusions have been reported on bone marrow biopsy from FAHN patients. It is unknown if such findings can be seen in peripheral macrophages.

Clinical features of FAHN

Affected patients typically develop a combination of dystonia and ataxia, along with optic atrophy. Spasticity typically occurs. Seizures may develop, along with progressive bulbar dysfunction. Peripheral neuropathy may be seen in some patients.

Kufor Rakeb syndrome (KRD)

Neuroradiologic findings in KRS

Radiographic findings in KRS may vary, and in fact, only a handful of patients have been reported with iron deposition in the pallidum and putamen (Figure 11). Widespread cerebral, cerebellum, and brainstem atrophy have been reported. Mutations in ATP13A2 are rare in patients with idiopathic NBIA (Kruer, unpublished).

Figure 11.

Kufor Rakeb

Laboratory abnormalities in KRS

No consistent laboratory features have been seen in KRS.

Clinical features of KRS

Initially characterized as a pallido-pyramidal syndrome, KRS patients may present with parkinsonism, pyramidal tract signs, dystonia, dementia, and psychosis, including frank hallucinations. Supranuclear gaze palsy may be evident, and anosmia may be seen, similar to other forms of inherited parkinsonism.

Static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA)

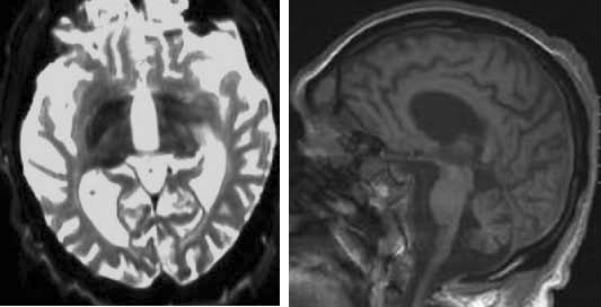

Neuroradiologic findings in SENDA

SENDA features T2 hypointensity, more pronounced in the substantia nigra/cerebral peduncles than in the globus pallidus. Characteristic features include the finding of T1 hyperintensity in the cerebral peduncles that sometimes extends into the globus pallidus (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

SENDA

Laboratory abnormalities in SENDA

No laboratory abnormalities have been identified in SENDA.

Clinical features of SENDA

Children with SENDA have a seemingly static encephalopathy initially, characterized by intellectual disability with or without concurrent spasticity. However, as a rule, they slowly gain skills for 1–3 decades before developing dystonia-parkinsonism in adulthood.

Conclusions

The most common clinical scenario encountered is one where iron deposition is identified in the globus pallidus, without an accompanying eye of the tiger sign, in a child or adolescent with dystonia and/or parkinsonism. Often, other clinical “clues” are absent. In such a case, it may be most appropriate to test for PLA2G6-associated disease first. Testing for PANK2- associated disease, followed by C19orf12 should then be considered.

Although complex, overlapping phenotypes are frequently seen in NBIA, the approach outlined here will facilitate the diagnosis of specific subtypes of the disorder. This approach will have to be refined with the identification of further NBIA syndromes and their genetic basis. However, the diagnostic algorithm we outline may facilitate diagnosis and have important implications for prognosis, genetic counseling, and clinical trial enrollment in the future.

Acknowledgements

Work in MCK's laboratory is supported by the Child Neurology Foundation, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, American Academy of Neurology, American Philosophical Society, and the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Autti T, Joensuu R, Aberg L. Decreased T2 signal in the thalami may be a sign of lysosomal storage disease. Neuroradiology. 2007 Jul;49(7):571–8. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Cummings J, Perlman S, Hance DB, Mintz J. Increased basal ganglia iron levels in Huntington disease. Arch Neurol. 1999 May;56(5):569–74. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery PF, Curtis AR, Fey C, Coulthard A, Crompton D, Curtis A, Lombes A, Burn J. Neuroferritinopathy in a French family with late onset dominant dystonia. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e69. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.5.e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery PF, Crompton DE, Birchall D, Jackson MJ, Coulthard A, Lombès A, Quinn N, Wills A, Fletcher N, Mottershead JP, Cooper P, Kellett M, Bates D, Burn J. Clinical features and natural history of neuroferritinopathy caused by the FTL1 460InsA mutation. Brain. 2007 Jan;130(Pt 1):110–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel LA, Jing Z, O'Brien DE, Sun M, Kotzbauer PT. Catalytic function of PLA2G6 is impaired by mutations associated with infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy but not dystonia-parkinsonism. PLoS One. 2010 Sep 23;5(9):e12897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna F, Barboni P, Liguori R, Valentino ML, Savini G, Gellera C, Mariotti C, Rizzo G, Tonon C, Manners D, Lodi R, Sadun AA, Carelli V. Visual system involvement in patients with Friedreich's ataxia. Brain. 2009 Jan;132(Pt 1):116–23. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garone C, Pippucci T, Cordelli DM, Zuntini R, Castegnaro G, Marconi C, Graziano C, Marchiani V, Verrotti A, Seri M, Franzoni E. FA2H-related disorders: a novel c.270+3A>T splice-site mutation leads to a complex neurodegenerative phenotype. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011 Oct;53(10):958–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig MB, Iuso A, Haack T, Kmiec T, Jurkiewicz E, Heim K, Roeber S, Tarabin V, Dusi S, Krajewska-Walasek M, Jozwiak S, Hempel M, Winkelmann J, Elstner M, Oexle K, Klopstock T, Mueller-Felber W, Gasser T, Trenkwalder C, Tiranti V, Kretzschmar H, Schmitz G, Strom TM, Meitinger T, Prokisch H. Absence of an orphan mitochondrial protein, c19orf12, causes a distinct clinical subtype of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Oct 7;89(4):543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick SJ, Penzien JM, Michl W, Sharif UM, Rosman NP, Wheeler PG. Cranial MRI changes may precede symptoms in Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25:166–9. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlden H, Lincoln S, Farrer M, Cleland PG, Hardy J, Orrell RW. Compound heterozygous PANK2 mutations confirm HARP and Hallervorden-Spatz syndromes are allelic. Neurology. 2003 Nov 25;61(10):1423–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000094120.09977.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miszkiel KA, Paley MN, Wilkinson ID, Hall-Craggs MA, Ordidge R, Kendall BE, Miller RF, Harrison MJ. The measurement of R2, R2* and R2' in HIV-infected patients using the prime sequence as a measure of brain iron deposition. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15(10):1113–9. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima H, Takahashi Y, Kono S. Aceruloplasminemia, an inherited disorder of iron metabolism. Biometals. 2003 Mar;16(1):205–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1020775101654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo JL, Muñoz E, Valldeoriola F, et al. The eye of the tiger sign in cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration. Mov Disord. 1999;14:169–71. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199901)14:1<169::aid-mds1033>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteghini, et al. 2012. This issue.

- Pierson TM, Simeonov DR, Sincan M, Adams DA, Markello T, Golas G, Fuentes-Fajardo K, Hansen NF, Cherukuri PF, Cruz P, James C Mullikin for the NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Blackstone C, Tifft C, Boerkoel CF, Gahl WA. Exome sequencing and SNP analysis detect novel compound heterozygosity in fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012 Apr;20(4):476–9. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadri M, Federico A, Zhao T, Breedveld GJ, Battisti C, Delnooz C, Severijnen LA, Di Toro Mammarella L, Mignarri A, Monti L, Sanna A, Lu P, Punzo F, Cossu G, Willemsen R, Rasi F, Oostra BA, van de Warrenburg BP, Bonifati V. Mutations in SLC30A10 Cause Parkinsonism and Dystonia with Hypermanganesemia, Polycythemia, and Chronic Liver Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 Mar 9;90(3):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder JM. Ferritinopathy: diagnosis by muscle or nerve biopsy, with a note on other nuclear inclusion body diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2005 Jan;109(1):109–14. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0949-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker K, Hesse S, Wegner F, et al. Eye of the tiger sign in multiple system atrophy. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:e1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuschl K, Clayton PT, Gospe SM, Jr, Gulab S, Ibrahim S, Singhi P, Aulakh R, Ribeiro RT, Barsottini OG, Zaki MS, Del Rosario ML, Dyack S, Price V, Rideout A, Gordon K, Wevers RA, Kling Chong WK, Mills PB. Syndrome of Hepatic Cirrhosis, Dystonia, Polycythemia, and Hypermanganesemia Caused by Mutations in SLC30A10, a Manganese Transporter in Man. Am J Hum Genet. 2012 Mar 9;90(3):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldvogel D, van Gelderen P, Hallett M. Increased iron in the dentate nucleus of patients with Friedrich's ataxia. Ann Neurol. 1999 Jul;46(1):123–5. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199907)46:1<123::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]