Abstract

Expression of the molecules that modulate the synthesis and action of estrogen in, or reflect function of, Sertoli cells was determined in the fetal testis of baboons in which estrogen levels were suppressed in the second half of gestation to determine whether this may account for the previously reported alteration in fetal testis germ cell development. P-450 aromatase, estrogen receptor (ER) β, and α-inhibin protein assessed by immunocytochemistry was abundantly expressed in Sertoli cells of the fetal baboon testis, but unaltered in baboons in which estrogen levels were suppressed by letrozole administration. Moreover, P-450 aromatase and ERα and β mRNA levels, assessed by real-time RT-PCR, were similar in germ/Sertoli cells and interstitial cells isolated from the fetal testis of untreated and letrozole-treated baboons. These results indicate that expression of the proteins that modulate the formation and action of estrogen in, and function of, Sertoli cells is not responsible for the changes in germ cell development in the fetal testis of estrogen-deprived baboons.

Keywords: Fetus, Testis, Development, Baboon, Estrogen

Introduction

The fetal testis undergoes substantial development in utero during human and nonhuman primate pregnancy, thereby providing the foundation for male reproductive function and fertility in adulthood. We have shown that the fetal testis at term in the baboon [1], as in the human [2–5] and rhesus monkey [6–9], is comprised of undifferentiated (i.e., type A) spermatogonia classified morphologically as dark (Ad) or pale (Ap), gonocytes, and Sertoli cells. The Ap spermatogonia are thought to be renewing spermatogonial stem cells that produce the differentiated type B sperma-togonia, the Ad spermatogonia are considered reserve spermatogonial stem cells which predict future fertility [10], while the gonocytes are thought to be precursors of type A spermatogonia [11, 12].

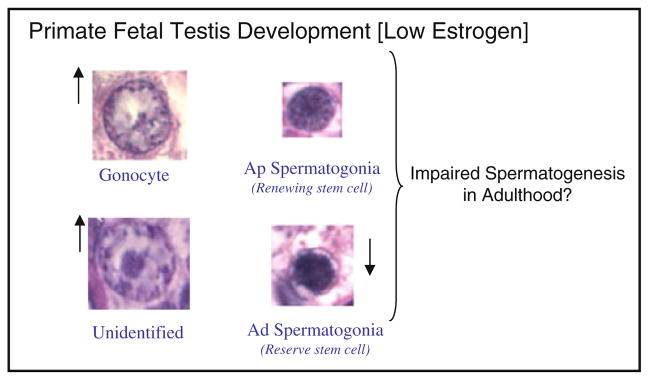

Despite the importance of fetal testis germ cell development to fertility in adulthood, very little is known about the in utero regulation of fetal testis maturation. That estrogen has an essential role in fetal testis development was discovered when it was found that estrogen receptor (ER) or P-450 aromatase knock-out mice exhibited alterations in testis and/or efferent ductule morphology/function and infertility [13–16]. Indeed, we have recently shown that the fetal baboon testis expresses ERα and β [17] and in the fetal testis of baboons in which estrogen levels were suppressed by administration of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole throughout the second half of gestation, the number of Ad spermatogonia was lower, gonocytes and unidentified cells greater and Ap spermatogonia and Sertoli cells unchanged than in untreated baboons [1, Fig. 1]. Based on these find-ings, we proposed that endogenous estrogen promotes fetal testis germ cell development and that the changes in the germ cell population in the estrogen-deprived baboon fetus would impair spermatogenesis and fertility in adulthood.

Fig. 1.

Impact of estrogen suppression throughout the second half of primate pregnancy on the numbers of gonocytes, type A pale (Ap) spermatogonia, unidentified cells, and type A dark (Ad) spermatogonia in the fetal testis and proposed impact on spermatogenesis in adulthood (modified from Albrecht et al. [1])

Sertoli cells, which express P-450 aromatase [18–20] and ERα and β [21] to modulate the formation and action of estrogen, respectively, as well as α-inhibin which is indicative of functional capacity, serve as the principal structural element of the seminiferous epithelium creating an environment which promotes the survival, development, and function of germ cells [22–24]. Therefore, in the present study P-450 aromatase, ERα and β, and α-inhibin were assessed in the fetal testis of baboons in which estrogen levels were suppressed throughout the second half of gestation by the administration of letrozole to determine whether expression of the molecules that modulate formation and action of estrogen in, or reflect function of, Sertoli cells are altered and may account for the alterations in germ cell development.

Results

Serum estradiol and testosterone levels

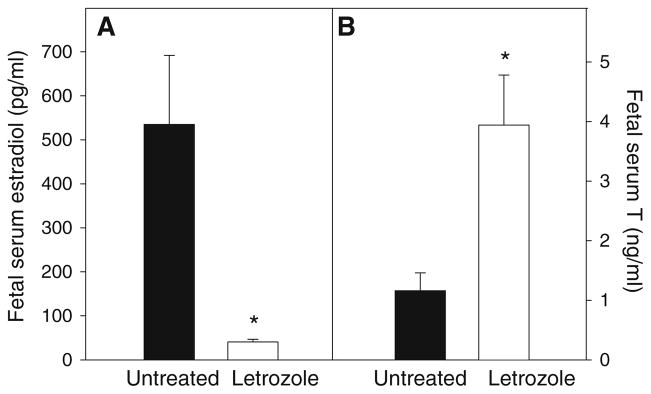

Maternal peripheral serum estradiol levels in untreated baboons increased (P < 0.01) from 1.10 ± 0.09 ng/ml (mean ± SE) on day 100 of gestation to 4.64 ± 0.94 ng/ml on day 165. Within 1–2 days after the onset of letrozole administration on day 100 of gestation, maternal peripheral serum estradiol levels decreased (P < 0.01) to and remained at <0.10 ng/ml throughout the remainder of gestation. Letrozole levels, quantified by HPLC, were 4.12 ng/ml in the maternal and 3.19 ng/ml in the fetal circulation at the time of delivery on day 165, indicating that the aromatase inhibitor readily crosses the placenta to suppress aromatization in the fetus as well as the placenta. Thus, on day 165 of gestation, umbilical vein (i.e., fetal) serum estradiol levels in letrozole-treated baboons (41 ± 6 pg/ml) were almost 95% lower (P < 0.001) than in untreated animals (535 ± 157 pg/ml, Fig. 2). In contrast, fetal serum testosterone levels were approximately 3.5-fold greater (P < 0.01) in letrozole-treated (3.94 ± 0.84 ng/ml) than in untreated (1.16 ± 0.30 ng/ml) baboons (Fig. 2), as a result of the inhibition of C19-steroid aromatization within the placenta.

Fig. 2.

Serum estradiol (a) and testosterone (T) (b) levels (means ± SE) on day 165 of gestation in male fetuses of baboons untreated (n = 6) or treated daily on days 100–164 of gestation with letrozole (115 μg/kg body weight/day, sc, n = 6). * P < 0.01 (Student’s t test)

Placental and fetal weights and Ad spermatogonia count

Fetal body weight and fetal testis weight were similar in untreated and letrozole-treated animals (Table 1). However, placental weight was 8% greater (P < 0.05) in letrozole-treated than in untreated baboons. The volume fraction of type Ad spermatogonia in the fetal testis of the letrozole-treated baboons in this study (0.33 ± 0.05/mg testis × 104) was approximately 50% lower (P < 0.01) than in untreated animals (0.62 ± 0.08/mg testis × 104, Table 1).

Table 1.

Placental, fetal body and fetal testis weights, and number of type Ad spermatogonia in untreated and letrozole-treated baboons

| Treatment | N | Placenta (g) | Body weight (g) | Testis weight (mg) | Ad spermatogonia/mg testis (×104) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 6 | 179 ± 8 | 831 ± 24 | 154 ± 10 | 0.62 ± 0.08 |

| Letrozole | 6 | 194 ± 16* | 852 ± 34 | 162 ± 6 | 0.33 ± 0.05** |

Fetuses obtained by cesarean section on day 165 of gestation from baboons untreated or treated on days 100–164 with letrozole (115 μg/kg body weight/day, sc)

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01 (Student’s t test)

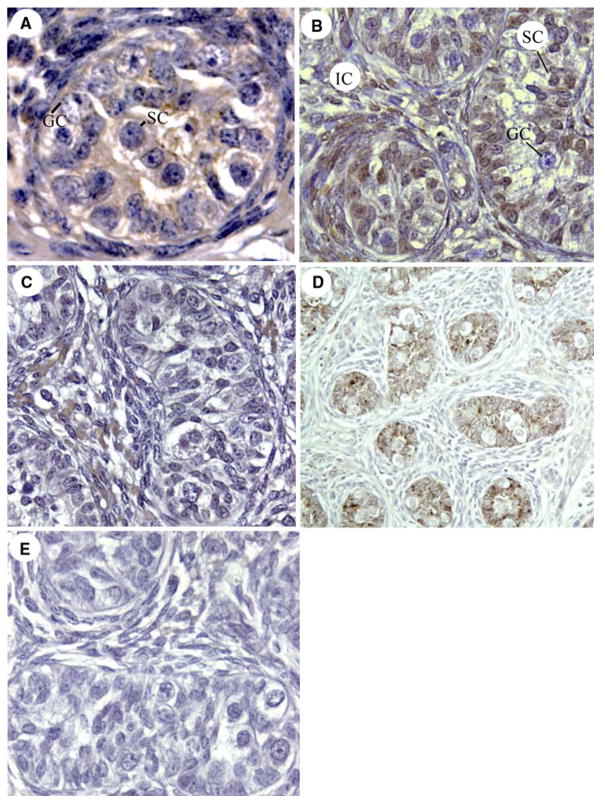

Immunocytochemistry of P-450 aromatase, ERβ, ERα, and α-inhibin protein

P-450 aromatase protein was localized by immunocytochemistry within the cytoplasm of Sertoli cells, but not germ cells, in the seminiferous cords and diffusely in interstitial cells of the fetal baboon testis (Fig. 3a). ERβ protein was abundantly expressed within the nuclei of Sertoli, peritubular, and interstitial cells, but not germ cells, of the fetal baboon testis (Fig. 3b). In contrast, ERα protein was minimally expressed in cells within the seminiferous cords and detected in moderate level in the nuclei of interstitial cells (Fig. 3c). α-Inhibin was abundantly expressed in Sertoli cells, but not in germ or interstitial cells, of the fetal baboon testis (Fig. 3d). The cellular immunolocalization and level of expression of P-450 aromatase, ERα and β and α-inhibin protein appeared similar in untreated and letrozole-treated baboons (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Immunocytochemical localization (brown precipitate) of P-450 aromatase (a), ERβ (b), ERα (c), and α-inhibin (d) in the fetal testis of untreated baboons on day 165 of gestation. e Negative control with omission of α-inhibin primary antibody. GC germ cell nucleus, SC Sertoli cell nucleus, IC interstitial cells.

Magnifications: ×400 (a–c, e); ×200 (d)

RT-PCR of P-450 aromatase, ERβ and α mRNA

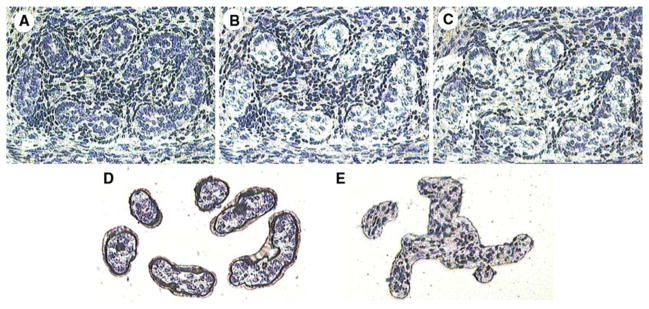

Figure 4 illustrates the laser capture microdissection (LCM) isolation of Sertoli and germ cells, collectively, from within the seminiferous cords (b) and interstitial cells (c) from the baboon fetal testis and their presence on the LCM cap (d, e) for mRNA analysis.

Fig. 4.

Illustration of laser capture microdissection (LCM) of cells from the fetal baboon testis. a Fetal testis section before LCM. b Remaining section after LCM removal of germ and Sertoli cells from within the seminiferous cords. c Remaining section after LCM removal of interstitial cells. d Germ and Sertoli cells on LCM cap. e Interstitial tissue on LCM cap

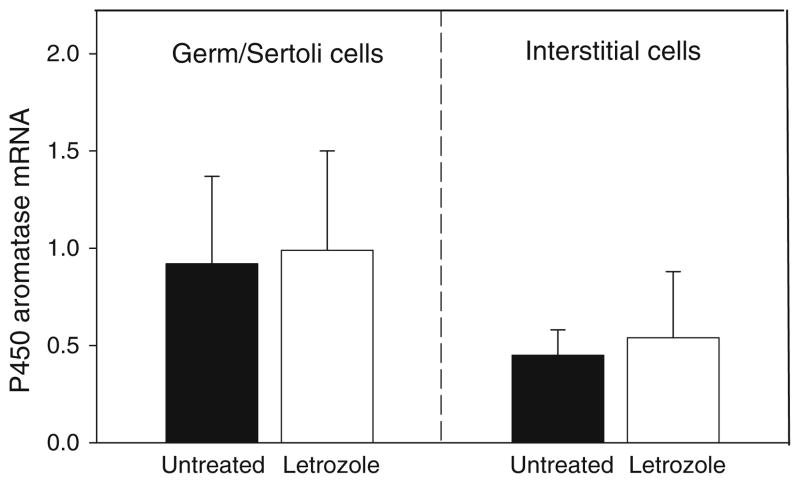

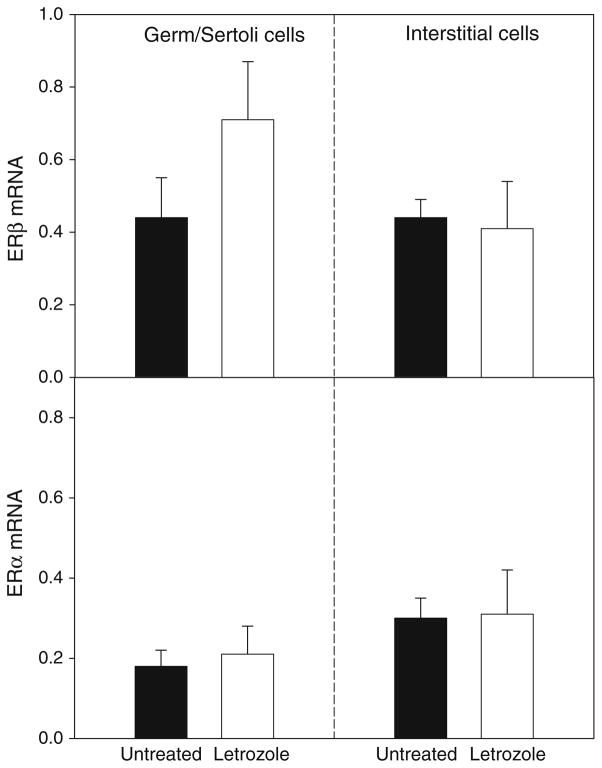

The mRNA levels for P-450 aromatase were twofold greater in the germ/Sertoli cells than in interstitial cells (Fig. 5), consistent with the abundant protein levels for this enzyme shown in the Sertoli cells (Fig. 3a). However, germ/Sertoli cell and interstitial cell P-450 aromatase mRNA levels were similar in untreated and letrozole-treated baboons (Fig. 5). ERβ mRNA levels, particularly in germ/Sertoli cells, were over twofold greater (P < 0.05) than ERα mRNA levels (Fig. 6), consistent with the more intense immunostaining for ERβ (Fig. 3b) than ERα (Fig. 3c) protein. However, ERβ and α mRNA levels both in germ/Sertoli cells and interstitial cells were similar in untreated and letrozole-treated animals (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

P-450 aromatase mRNA/18S rRNA levels (means ± SE) quantified by real-time RT-PCR in germ/Sertoli cells and interstitial cells isolated via LCM from the fetal testis on day 165 of gestation from baboons untreated or treated on days 100–164 of gestation with letrozole as detailed in the legend of Fig. 2

Fig. 6.

ERβ and α mRNA/18S rRNA levels quantified by real-time RT-PCR in germ/Sertoli cells and interstitial cells isolated via LCM from the fetal testis of the same baboons in which P-450 aromatase mRNA levels are shown in Fig. 5

Discussion

The present study showed that expression of P-450 aromatase, ERα and β and α-inhibin was not altered late in gestation in the fetal testis of baboons in which the production and levels of estrogen had been suppressed by administration of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole throughout the second half of gestation. These results indicate that the levels of endogenous estrogen typical of the second half of gestation are not required to maintain the expression of these proteins in the primate fetal testis, particularly in Sertoli cells which were a major site of expression of P-450 aromatase, ERβ, and α-inhibin. However, it remains to be determined whether estrogen regulates expression of the latter genes within the fetal testis earlier in pregnancy. Since letrozole binds reversibly to the P-450 aromatase heme region to suppress estrogen synthesis by inhibiting the activity not the transcription/translation of this enzyme, it was not unexpected that fetal testis P-450 aromatase mRNA and protein expression were retained after letrozole treatment of baboons. Although androgens have been shown to stimulate P-450 aromatase expression in other tissues, such as the rodent epididymis [25] and Leydig cells [26], the elevation in testosterone which occurred in letrozole-treated baboons of the current study had no effect on fetal testis P-450 aromatase mRNA levels or protein immunoexpression.

We have recently shown that the numbers of Ad spermatogonia, a reserve stem cell, were lower and gonocytes, an Ap spermatogonia precursor, were greater in the fetal testis of baboons deprived in utero of estrogen [1], supporting the concept of a role for estrogen in promoting fetal testis germ cell development. Consistent with the latter finding, the number of Ad spermatogonia was almost 50% lower in letrozole-treated than in untreated baboons of the current study. It appears, therefore, based on the results of the current study that the changes in fetal testis germ cell maturation were not associated with an alteration in expression of the P-450 aromatase enzyme responsible for catalyzing the biosynthesis, or the receptors required to mediate the action, of estrogen locally within the testis. Moreover, although Sertoli cells have an important role in nurturing and promoting the development and viability of germ cells [22–24, 27], the absence of a change in Sertoli cell-specific expression of α-inhibin suggests that the functional capacity of Sertoli cells was not altered and thus may also not account for the defect in germ cell development exhibited in estrogen-suppressed baboons fetuses. Sertoli cell number also was not changed in ERα or β [28] or P-450 aromatase [29] null mice. However, since umbilical vein serum estradiol levels in letrozole-treated baboons, albeit very low, were detectable, a threshold level of estrogen may exist in which Sertoli cell function was retained despite the change in germ cell development.

Although Sertoli cell ERβ expression was similar in the fetal testis of untreated and letrozole-treated baboons, the extensive localization of ERβ in Sertoli cells, but not in germ cells, shown previously [21, 30] and in the present study supports the concept that the regulatory effect of estrogen on germ cell maturation in the male fetus may be indirect via its action on Sertoli cells. However, in vitro studies in the adult rat and human testis show that estrogen has the capacity to directly stimulate proliferation and suppress apoptosis of germ cells [31–33], although caspase-3 expression in type A spermatogonia was not altered in the fetal testis of letrozole-treated baboons previously studied [1]. Moreover, Leydig cell development and function in the mouse testis were suppressed by estrogen [34], and the disruption of spermatogenesis which occurs in ERα-null mice has been reported to be due to increased tubule pressure resulting from a reduction in efferent duct fluid resorption [14, 35]. Therefore, the role of estrogen on testis development and function appears extensive and complex [36] and an indirect effect of estrogen in regulating germ cell development via components other than Sertoli cells is certainly possible. Moreover, since maternally administered letrozole crossed the placenta to the fetus in baboons of the present study, letrozole may exert effects on the testis via a mechanism not related to its ability to inhibit aromatization.

Because serum testosterone levels were increased by letrozole inhibition of aromatization in the baboon fetus, and endogenous androgens inhibited gonocyte proliferation in fetal mice [37], it is possible that the disruption of germ cell development in letrozole-treated baboons resulted from the elevation in androgen. However, germ cells do not express the androgen receptor in the fetal baboon [17] and human [19] testis, while androgens typically promote seminiferous epithelial integrity [38] and spermatogenesis [39] via the androgen receptor which is expressed in the adult Sertoli cell [40]. Therefore, although we recognize that the increase in androgen may account for the observed change in fetal testis germ cell development in letrozole-treated baboons, we propose that this resulted from the decline in estrogen. Additional study, including administration of both letrozole plus estradiol or testosterone alone, is needed to establish the mechanisms underlying the alteration in testis germ cell development observed in baboon fetuses after maternal letrozole treatment.

In summary, expression of P-450 aromatase, ERα and β, and α-inhibin in the fetal baboon testis was unaltered by suppressing estradiol production and levels during the second half of gestation. These results suggest that the expression of the latter proteins that modulate the formation and action of estrogen in, and function of, Sertoli cells is not responsible for the changes in germ cell development in the fetal testis of estrogen-deprived baboons.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female baboons (Papio anubis) weighing 12–18 kg were housed individually in stainless steel cages in air-conditioned quarters and fed primate chow (Teklad-Harlan, St. Louis, MO) and fresh fruit and/or vegetables twice daily and water ad libitum. Females were paired with males for 5 days at the anticipated time of ovulation and pregnancy subsequently confirmed by ultrasonography. Maternal peripheral saphenous blood samples (3 ml) were obtained at 1–4 days intervals during the study period and from the umbilical vein at the time of placental–fetal delivery, and serum stored at −20°C until assayed for estradiol and testosterone levels by RIA as described previously [41].

Placentas and fetuses were obtained by cesarean section on day 165 of gestation (term = day 184) from baboons untreated (n = 6) or treated with the highly specific aromatase inhibitor letrozole (4,4-[1,2,3-triazol-lyl-methylene]-bis-benzonitrite, Norvartis Pharm AG, Basel, Switzerland; 115 μg/kg body weight/day sc, n = 6) on days 100–164 of gestation, as described previously [1]. The fetuses were euthanized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg body weight; Euthasol, Vibrec, Inc.) and the fetal testes removed weighed and one gland frozen with dry ice in cryomolds and stored at −80°C for mRNA analysis and the other gland fixed in Bouin’s and embedded in paraffin for quantification of Ad spermatogonia and immunocytochemistry.

Morphometric quantification of Ad spermatogonia

Morphometric quantification of type Ad spermatogonia was performed by the established methods of Marshall et al. [42]. The volume fraction of cells was determined by the point-counting method using a grid of intersecting lines placed over the tissue sections. The ratio of the number of test points (intersections on grid) overlying the tissue and the total number represented the volume fraction of cells which was corrected by the method of Abercrombie [43]. The total number of Ad spermatogonia per testis was calculated by the absolute volume (i.e., volume fraction of cell nuclei × testis weight ÷ specific gravity of testis) of all nuclei divided by the mean nuclear volume. The total number of cells per testis was then divided by whole testis weight.

Immunocytochemistry

Sections (4 μm) of paraffin-embedded testis were boiled in 0.01 M Na citrate for antigen retrieval, incubated with hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxidase, incubated with 5% normal horse serum in KPBS to block non-specific binding, and immunocytochemistry performed as described previously [17]. Briefly, samples were incubated (4°C) overnight with rabbit polyclonal antibody to P-450 aromatase (1:2,000 final dilution in PBS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), rabbit polyclonal antibody to ERβ (1:200 final dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), mouse monoclonal antibody to human ERα (1:50 final dilution, Novacastra/Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), or mouse monoclonal antibody to α-inhibin (1:100 final dilution, AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK). Tissue sections were then incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or antimouse IgG (1:600 each, Novacastra/Vector) avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (ABC Elite, Novacastra, Vector), developed using diaminobenzidene–imidazole–H202 (Sigma) and lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative controls included omission of the primary antibody or substitution of the secondary immunoglobulin with one raised against a different species (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA).

Cell isolation by LCM

The fetal testis was sectioned at 8 μm via a cryostat (Lieca Corp., Deerfield, IL) and mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher Scientific, Suwanee, CA) at room temperature. Sections were fixed in 70% ethanol for 30 s, stained in hematoxylin for 10 s, dehydrated in 100% ethanol, incubated in xylene, and stored in a desiccator. Sertoli cells and germ cells, collectively, from 8 to 10 randomly selected seminiferous cords and cells from the interstitial tissue were isolated using an Arcturus PixCell II LCM system equipped with an Olympus microscope (Arcturus Engineering, Inc., Mountain View, CA) set at 60 mW, 3–5 ms capture duration, and laser spot size of 15.0 μm. The cell isolates were extracted via Nonidet P-40 guanidine isothiocyanate silica gel spin column centrifugation (Rneasy; QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) and RNA lysates stored overnight at −80°C.

Reverse transcription (RT)–real time PCR

P-450 aromatase primers: Oligonucleotide primers for P-450 aromatase were synthesized by the Biopolymer/Genomics Core Facility at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD) and based on Suzuki et al. [44]. The P-450 aromatase primers were upstream, 5′-GTGAAA AAGGGGACAAACAT-3′ (positions 1286–1305), and downstream, 5′-TGGAATCGTCTCAGAAGTGT-3′ (positions 1500–1481).

ERβ primers: Oligonucleotide primers for ERβ were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and based on the human cDNA sequence described by Ogawa et al. [45]. The ERβ primers were upstream, 5′-TTCCCAGCAATGT CACTAACT-3′ (positions 271–291), and downstream, 5′-CTCTTTGAACCTGGACCAGTA-3′ (positions 529–509).

ERα primers: Oligonucleotide primers for ERα were synthesized by Invitrogen and based on the human cDNA sequence described by Green et al. [46]. The ERα primers were upstream, 5′-GATCCTACCAGACCCTTCAG-3′ (positions 1226–1245), and downstream, 5′-TTCCAGAGA CTTCAGGGTGC-3′ (positions 1642–1623).

18S rRNA primers: Oligonucleotide primers for 18S were synthesized by Invitrogen and based on the human gene sequence (National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence database, Accession no. M10098). The 18S rRNA primers were upstream, 5′-TCAAGAACGAAA GTCGGAGG-3′ (positions 1126–1145), and downstream, 5′-GGACATCTAAGGGCATCACA-3′ (positions 1614–1595).

RT and real-time PCR: RT of total RNA from LCM isolates was performed according to manufacturer’s directions (Invitrogen). A 13 μl reaction containing 1 mM each of deoxy (d)-ATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 1× RT buffer, 250 ng random primers and total RNA was incubated at 65°C for 5 min then on ice for 1 min. Reaction buffer, 0.1 M DTT, 200 U Superscript III RT (Invitrogen) and 40 U RNAguard (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) were added to create a final 20 μl reaction volume that was incubated at 25°C for 5 min then at 50°C for 60 min. The RT reaction was terminated by heat inactivation of the enzyme at 70°C for 15 min and cooled to 4° C.

P-450 aromatase, ERβ and α mRNA levels were quantified by efficiency-corrected calibrator-normalized relative RT-PCR using LightCycler SYBR Green 1 technology (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Penzberg, Germany). An aliquot (1 μl) of the RT reaction mixture was added to 19 μl of LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green 1 reaction mix containing the gene-specific primers. The reaction pro-file consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 8 min, 50 cycles of amplification (95°C for 5 s, 55–59°C for 5 s and 72°C for 16–20 s), and product formation measured and displayed in real time. Due to the limited amount of total RNA collected by LCM, the levels of 18S rRNA were quantified by real-time PCR to serve as the reference gene with mRNA levels expressed as a ratio of 18S rRNA. Efficiency-corrected, calibrator-normalized relative quantification was performed with Roche analysis software (LightCycler version 4), which uses the concentration and efficiency of pre-made standard curves specific for each product to correct for differences in the efficiencies of target and reference genes, and an in-run calibrator to normalize quantification. We have confirmed that the RNA isolated from LCM-captured cells exhibited distinct 28S and 18S rRNA bands, and the input cDNA resulting from RT-PCR was of high quality. Specificity of the products was confirmed by melting curve analysis, agarose gel electrophoresis, and inclusion of negative controls with no template or no RT in the reaction.

Acknowledgments

The study is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH through Cooperative Agreement U54 HD36207 to the University of Maryland as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research. The secretarial assistance of Mrs. Wanda James with preparation of the manuscript is greatly appreciated. We thank Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland) for generously providing the aromatase inhibitor letrozole to conduct this study.

Contributor Information

Thomas W. Bonagura, Departments of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductive Sciences, and Physiology, Center for Studies in Reproduction, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Bressler Research Laboratories 11-019, 655 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

Hui Zhou, Departments of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductive Sciences, and Physiology, Center for Studies in Reproduction, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Bressler Research Laboratories 11-019, 655 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Jeffery S. Babischkin, Departments of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductive Sciences, and Physiology, Center for Studies in Reproduction, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Bressler Research Laboratories 11-019, 655 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

Gerald J. Pepe, Department of Physiological Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA

Eugene D. Albrecht, Email: ealbrech@umaryland.edu, Departments of Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductive Sciences, and Physiology, Center for Studies in Reproduction, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Bressler Research Laboratories 11-019, 655 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA

References

- 1.Albrecht ED, Lane MV, Marshall GR, Merchenthaler I, Simoranagkir DR, Pohl CR, Plant TM, Pepe GJ. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:406–414. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gondos B, et al. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1971;119:1. doi: 10.1007/BF00330535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aslan AR, Kogan BA, Gondos B. In: Neonatal Physiology Fetal. Polin RA, Fox WW, Abman SH, editors. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Shaughnessy PJ, Baker PJ, Monteiro A, Cassie S, Bhattacharya S, Fowler PA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4792–4801. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaskell TL, Esnal A, Robinson LL, Anderson RA, Saunders PT. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:2012–2021. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clermont Y. Physiol Rev. 1972;52:198–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rooij DG, van Alphen MM, van de Kant HJ. Biol Reprod. 1986;35:587–591. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simorangkir DR, Marshall GR, Plant TM. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4984–4989. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simorangkir DR, Marshall GR, Ehmcke J, Schlatt S, Plant TM. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1109–1115. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.044404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadziselimvic F, et al. Horm Res. 2001;55:6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clermont Y, Leblond CP. Am J Anat. 1959;104:237–273. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001040204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fouquet JP, Dadoune JP. Biol Reprod. 1986;35:199–207. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher CR, Graves KH, Parlow AF, Simpson ER. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6965–6970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess RA, Bunick D, Bahr J, Taylor JA, Korach KS, Lubahn DB. Nature. 1997;390:509–512. doi: 10.1038/37352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess RA, Bunick D, Lubahn DB, Zhou Q, Bourna J. J Androl. 2000;21:107–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albrecht ED, Billiar RB, Aberdeen GW, Babischkin JS, Pepe GJ. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1106–1113. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorrington JH, Khan SA. In: The Sertoli Cell. Russell LD, Griswold MD, editors. Cache River Press; Clearwater, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berensztein EB, Baquedano MS, Gonzalez CR, Saraco NI, Rodriguez J, Ponzio R, Rivarola MA, Belgorosky A. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:740–744. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000246072.04663.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carreau S, Delalande C, Silandre D, Bourguiba S, Lambard S. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas TF, Siu ER, Esteves CA, Monteiro HP, Oliveira CA, Porto CS, Lazari MF. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:101–114. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.063909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell LD, Griswold MD. In: The Sertoli Cell. Russell LD, Griswold MD, editors. Cache River Press; Clearwater, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterssen C, Söder O. Horm Res. 2006;66:153–161. doi: 10.1159/000094142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skinner MK. Endocr Rev. 1991;12:45. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shayu D, Rao AJ. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;249:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genissel C, Carreau S. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;178:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinkevicius KW, Laine M, Lotan TL, Woloszyn K, Richburg JH, Greene GL. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1898–2905. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould ML, Hurst PR, Nicholson HD. Reproduction. 2007;134:179–271. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson KM, O’Donnell L, Jones MEE, Meachem SJ, Boon WC, Fisher CR, Graves KH, McLachlan RI, Simpson ER. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:7986–7991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders PT, Sharpe RM, Williams K, Macpherson S, Urquart H, Irvine DS, Millar MR. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:227–236. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wahlgren A, Svechnikov K, Strand ML, Jahnukainen K, Parvinen M, Gustafsson JǺ, Söder O. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2917–2922. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pentikainen V, Erkkila K, Suomalainen L, Parvinen M, Dunkel L. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2057–2067. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.5.6600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thuillier R, Mazer M, Manku G, Boisvert A, Wang Y, Culty M. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:825–836. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delbes G, Levacher C, Doquenne D, Racine C, Pakarinen P, Habert R. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2454–2461. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hess RA. Rev Reprod. 2000;5:84–92. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0050084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akingbemi BT. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merlet J, Racine C, Moreau E, Moreno SG, Habert R. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:3615–3620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang RS, Yeh S, Chen LM, Lin HY, Zhang C, Ni J, Wu CC, di Sant’Agnese PA, deMesy-Bentley KL, Tzeng CR, Chang C. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5624–5633. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Shaughnessy PJ, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Monteiro A, Abel MH. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2343–2348. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sneddon SF, Walther N, Saunders PT. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5304–5312. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albrecht ED, Aberdeen GW, Pepe GJ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:432–438. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall GR, Jockenhövel F, Lüdecke D, Nieschlag E. Acta Endocrinol. 1986;113:424–431. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1130424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abercrombie M. Anat Rec. 1946;94:239–247. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki T, Miki Y, Moriya T, Shimada N, Ishida T, Hirakawa H, Ohuchi N, Sasano H. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4670–4676. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Hiroi H, Orimo A, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Maramatsu M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:122–126. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A, Bornert JM, Argos P, Chambon P. Nature. 1986;320:134–139. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]