Abstract

OBJECTIVE

High fat diets increase the risk for insulin resistance by promoting inflammation. The cause of inflammation is unclear, but germfree mouse studies have implicated commensal gut bacteria. We tested whether diet-induced obesity, diabetes, and inflammation are associated with anti-bacterial IgG.

MATERIALS/METHODS

Blood from lean and obese healthy volunteers or obese patients with diabetes were analyzed by ELISA for IgG against extracts of potentially pathogenic and pro-biotic strains of Escherichia coli (LF-82 and Nissle), Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, and Lactobacillus acidophilus, and for circulating Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα). C57Bl/6 mice were fed low- or high- fat diets (10 or 60% kcal from fat) for 10 weeks and tested for anti-bacterial IgG, bodyweight, fasting glucose, and inflammation.

RESULTS

Obese diabetic patients had significantly more IgG against extracts of E. coli LF-82 compared with lean controls, whereas IgG against extracts of the other bacteria was unchanged. Circulating TNFα was elevated and correlated with IgG against the LF-82 extract. Mice fed high-fat diets had increased fasting glucose levels, elevated TNFα and neutrophils, and significantly more IgG against the LF-82 extracts.

CONCLUSIONS

Diabetes in obesity is characterized by increased IgG against specific bacterial antigens. Specific commensal bacteria may mediate inflammatory effects of high-fat diets.

Keywords: Inflammation, microbiome, diabetes, antibodies, fat

Introduction

Insulin signaling is sensitive to inflammation [1], and inflammatory stimuli can induce glucose intolerance [2-3]. High fat diets are thought to initiate inflammation in expanding adipose tissues [4-6], presumably through direct activation of innate immune receptors by dietary saturated fatty acids [7-8]. However, germfree mice are resistant to diet-induced obesity and inflammation [9-12], suggesting that inflammation is dependent on interactions between the diet and commensal bacteria. High fat diets promote absorption of bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [2; 13], which can induce adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance [2-3], and also promote translocation of bacteria into visceral adipose tissue [14]. Alternatively, inflammation due to high-fat diet/bacteria interactions may originate in the intestine and subsequently cascade to surrounding visceral fat [9].

While there is mounting evidence for a direct role of the gut microbiome in diet-induced insulin resistance, this has not been conclusively demonstrated in obesity-associated diabetes. To shed more light onto this issue we tested whether diabetes in obesity is associated with inflammatory immune responses against specific gut bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Test subjects

Plasma was obtained from 32 obese individuals participating in a Health Management Resources (HMR®) weight loss clinic and from 10 healthy lean volunteers at Biospecialty Corp. (Colmar, PA, USA). Donor parameters are listed in Table 1. Half of the obese donors had diabetes and were being treated with insulin, insulinotropes, metformin, glyburide, PPARγ agonists, or combinations thereof. Nine obese subjects with diabetes and 5 obese controls were on statins, none were smokers. All samples were obtained with approval from relevant Institutional Review Boards and with informed written consent. Samples were stored at -86°C until use.

Table 1.

Relevant parameters of plasma donors

| Lean (n=10) | Obese (n=16) | Obese, diabetes (n=16) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body-mass index | 24.8 ± 3.0 | 41.1 ± 10.4 | 40.6 ± 7.1 |

| Gender | 1F, 9M | 7F, 9M | 7F, 9M |

| Age | 42.3 ± 11.2 | 50.8 ± 17.0 | 59.2 ± 7.2 |

Anti-bacterial IgG and TNFα measurements

Total (free and soluble-receptor bound) TNFα was measured in 2x diluted human plasma with an ELISA from eBioscience (BMS223HS; sensitivity 0.13 pg/mL) and in mouse plasma with a multiplex ELISA (Millipore Corp.). To detect anti-bacterial IgG, we developed an ELISA as follows: Extracts of overnight cultures of Escherichia coli strains LF-82 (a pathogenic strain isolated from a patient with Crohn's disease [15]) and Nissle (a non-pathogenic strain), Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, or Lactobacilus acidophilus grown in Lysogeny Broth, were prepared using a detergent-based bacterial protein extraction kit (“B-Per”; Pierce Biotechnology). The extracts likely contained a mix of lipid, protein, and sugar antigens from cytoplasm, membranes and cell walls. Extracts (10 μg protein / well) were coated onto 96 well flat-bottom ELISA plates (BD-Falcon) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). After blocking (“NAP” buffer; G-Biosciences), 400x dilutions of human or 100x dilutions of mouse plasma were added in triplicate, and bound IgG was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human or mouse IgG (Fc specific) antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). A chromogenic substrate (p-Nitrophenyl phosphate; Sigma-Aldrich) was added, and the color reaction was stopped with 3M sodium hydroxide. Absorbance at 450 nm (A450) was measured in a Bio-Rad microplate reader.

Mouse studies

Male C57Bl/6 mice, ordered at 5 weeks of age (Jackson Laboratories), were housed three per cage in a specific pathogen-free animal facility with a 12h light / dark cycle, and were used at 6 weeks of age. One group was fed a diet with 60% of kcal from fat (diet D12492 from Research Diets Inc.), the other a diet with 10% of kcal from fat (D12450B). The animals were euthanatized after 10 weeks, after a fasting (4h) blood glucose measurement (TrueTrack glucose meter; Home Diagnostics Inc). Plasma anti-bacterial IgG and TNFα were measured as described above; blood neutrophils with a Coulter counter (Perkin Elmer). All animals were handled in accordance with good animal practice as defined by the relevant national and local animal welfare bodies, and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M and were analyzed with GraphPad Prism v5.04. Groups were compared with unpaired Student's t-tests or Anova and Bonferroni's post-hoc analysis. Statistical significance was assumed when P<0.05.

Results

Increased IgG against extracts of E. coli LF82 in plasma of obese patients with diabetes correlates with TNFα

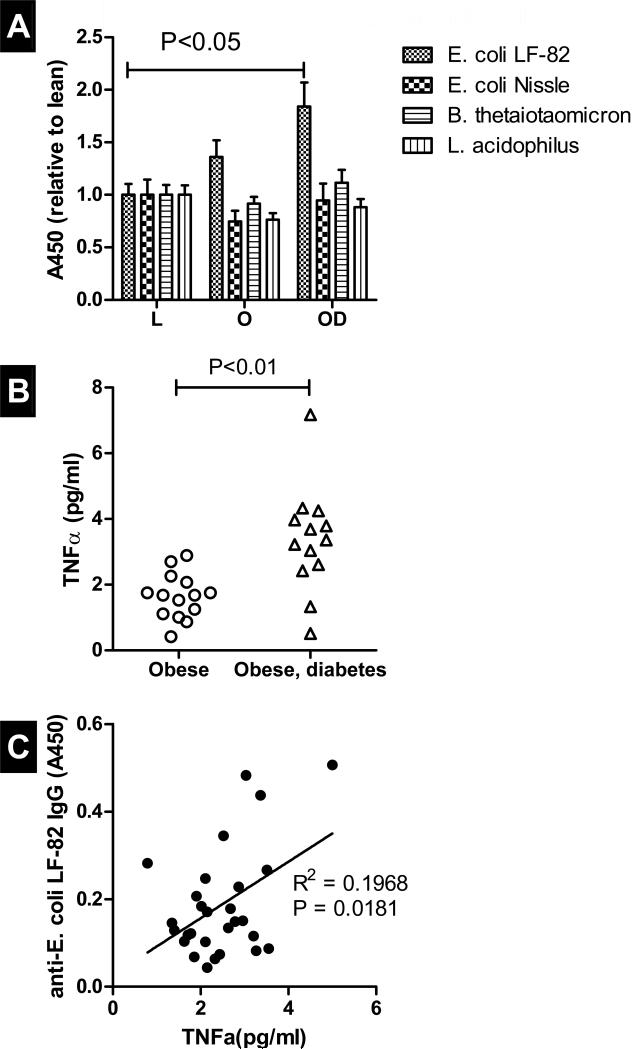

IgG against E. coli LF-82 extracts was lowest in lean subjects and highest in obese subjects with diabetes, with significant difference between obese diabetics and lean controls (Figure 1A; P<0.05). IgG against the other bacterial extracts (E. coli Nissle, B. thetoiotaomicron and L. acidophilus) was not different between groups. TNFα levels in obese diabetic patients were significantly higher than in obese controls (Figure 1B; P<0.05), and TNFα correlated with IgG against the LF-82 extract (Figure 1C; P<0.05).

Figure 1.

IgG against extracts of E. coli (strains LF-82 and Nissle), B. thetaiotaomicron, and L. acidophilus in plasma from lean and obese controls and obese patients with diabetes (A). Shown are A450 (average ± S.E.M) obtained with plasma from lean controls (“L”; n=10), obese controls (“O”; n=16) and obese patients with diabetes (“OD”; n=16). Values are normalized for those of lean controls. Panel B shows TNFα in the blood of obese controls and obese diabetic patients; panel C shows a positive correlation between IgG against extracts of E. coli LF-82 and TNFα. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between groups (T-test, P<0.05)

Increased IgG against extracts of E. coli LF-82 in plasma from mice fed high-fat diets

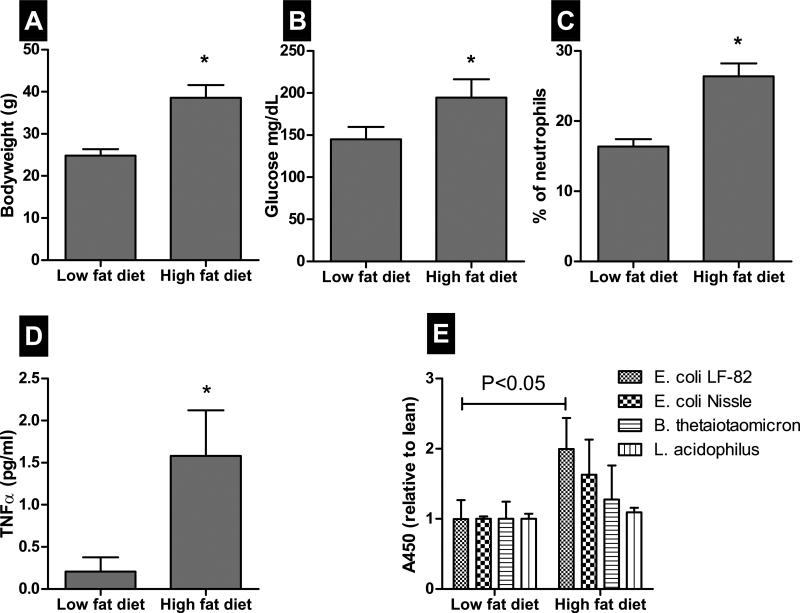

As expected, mice on the high fat diet gained more weight (Figure 2A; P<0.005) and had higher fasting glucose levels (Figure 2B; P<0.001), suggesting impaired glucose homeostasis. Mice on the high fat diet also had elevated neutrophil counts (Figure 2C; P<0.001) and circulating TNFα (Figure 2D; P<0.05), indicating systemic inflammation. They also had significantly higher IgG against the LF-82 extract (Figure 2E; P<0.05), but IgG against the other extracts was not significantly different.

Figure 2.

Body weight (A), fasting glucose (B), % neutrophils in the white-blood fraction (C), total TNFα (D), and anti-bacterial IgG (E) in blood and plasma from C57Bl/6 mice (n=6 per group) on low- or high- fat diets for 10 weeks. Shown are average ± S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between groups (P<0.05).

Discussion

Our study made two novel observations. First, diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance in mice was associated with increased IgG against antigens of pathogenic E. coli. Second, IgG against such extracts was significantly elevated in obese individuals with diabetes, but not without diabetes, and IgG correlated with TNFα. This would suggest that specific components of the intestinal microbiome can contribute to diet-induced metabolic inflammation and that profiling of IgG against bacterial antigens could help predict diabetes in obese subjects. However, it is unclear whether IgG responses are cause or consequence, and the identity of relevant bacteria and bacterial antigens remains unknown.

Recent studies have established a role for the gut microbiome in diet-induced metabolic inflammation of adipose tissue [9; 14]. However, while the composition of the gut microbiome changes during diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [12; 16], it is unclear which species are responsible. We hypothesized that such species could be identified by analyzing cognate Immunoglobulin G. Indeed, IgG against extracts of E. coli LF-82 were increased in obese individuals whereas IgG against non-pathogenic E. coli or other bacteria was not elevated. However, it is not possible to conclude that it is the LF-82 strain against which IgG was directed. LF-82 was isolated from the intestine from one particular patient with Crohn's Disease [15] and it is unlikely that this particular strain is present in all humans, let alone in C57Bl/6 mice. Our extract likely contained several antigens that could be shared among various potentially pro-inflammatory strains or species and cross-react with IgG. We are currently attempting to determine the nature of these antigens.

Importantly, one could argue that increased anti-bacterial IgG simply reflects translocation, and there are indications for increased gut leakiness in obesity [17-18]. However, each engagement of translocated bacteria with cognate IgG has the potential to induce an inflammatory response through activation of FcγRIIa and other IgG receptors. Over time, such repeat inflammatory insults could set the stage for chronic inflammation and insulin resistance.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Dr Charlotte Kaetzel from the Immunology Department for donating the bacterial strains and for helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants 5P20RR021954, 5R21AI088605 and UL1RR033173

Abbreviations

- ELISA

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

LT and NM equally contributed to this manuscript and performed the experiments. AJ provided blood samples. EE and WdV wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

Nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta NN, McGillicuddy FC, Anderson PD, et al. Experimental endotoxemia induces adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes. 2010;59:172–81. doi: 10.2337/db09-0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:1796–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:1821–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:3015–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suganami T, Tanimoto-Koyama K, Nishida J, et al. Role of the Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB pathway in saturated fatty acid-induced inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251608.09329.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding S, Chi MM, Scull BP, et al. High-fat diet: bacteria interactions promote intestinal inflammation which precedes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance in mouse. PLoS ONE. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, et al. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabot S, Membrez M, Bruneau A, et al. Germ-free C57BL/6J mice are resistant to high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and have altered cholesterol metabolism. Faseb J. 2010 doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Altered Gut Microbiota in Mice Lacking Toll-Like Receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghoshal S, Witta J, Zhong J, et al. Chylomicrons promote intestinal absorption of lipopolysaccharides. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50:90–97. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800156-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amar J, Chabo C, Waget A, et al. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100159. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Neut C, Barnich N, et al. Presence of adherent Escherichia coli strains in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1405–13. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, et al. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Leo VD, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G518–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gummesson A, Carlsson LMS, Storlien LH, et al. Intestinal Permeability Is Associated With Visceral Adiposity in Healthy Women. Obesity. 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]