Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the effect of genetic variants in fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene on metabolic syndrome (MetS). A systematic literature search was performed and random-effects meta-analysis was used to evaluate genetic variants in FTO with MetS. A gene-based analysis was conducted to investigate the cumulative effects of genetic polymorphisms in FTO. A total of 18 studies from 13 published papers were included in our analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis yielded an estimated odds ratio of 1.19 (95% CI 1.12–1.27; P = 1.38 × 10−7) for rs9939609, 1.19 (95% CI 1.05–1.35; P = 0.008) for rs8050136, and 1.89 (95% CI 1.20–2.96; P = 0.006) for rs1421085. The gene-based analysis indicated that FTO is strongly associated with MetS (P < 10−5). This association remains after excluding rs9939609, a SNP that was frequently reported to have strong association with obesity and MetS. In this study, we concluded that the FTO gene may play a critical role in leading to MetS. Targeting this gene may provide novel therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, FTO, Polymorphism, Meta-analysis, Gene-based analysis

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a cluster of metabolic abnormalities, including abdominal obesity, high triglycerides, diminished high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, high blood pressure and elevated fasting glucose [1]. First described by Reaven [2] as ‘syndrome X’, MetS have a number of definitions published by different organizations, including the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) [3], the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [4] and the World Health Organization (WHO) [5], and many others [6, 7]. The ATP III has become the most widely used definition, primarily due to its easiness in the diagnosis of MetS [8].

Metabolic syndrome is a complex disorder that has strong genetic predispositions [9–14]. Fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene is located in chromosome region 16q12.2 [15] and is found to play a critical role in energy balance system [16]. Genetic polymorphisms in FTO have been found to be associated with obesity [17–24] and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [25, 26]. Since obesity and T2D are key features of MetS, it is not surprising that many genetic variants in FTO could also be associated with risks for MetS [27–31]. However, conflicting results were reported [26, 32–37].

In this study, we conducted a meta-analysis of the association of several genetic variants in FTO with MetS. Because MetS is a complex disorder, it is very likely that individual SNPs may contribute little to the onset and development of MetS. However, their combined effects may be significant. We therefore conducted a gene-based analysis to investigate the cumulative effects of the genetic variants in FTO on MetS.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We did an extensive literature search in September 2011 in MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Search terms included “metabolic syndrome”, “syndrome X”, “genetic variant”, “SNP”, “polymorphism” and “FTO”. Studies were included in our analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) studies on human subjects; (2) provided a clear definition of metabolic syndrome; (3) reported association of individual SNPs in FTO with MetS; and (4) provided odds ratios (OR) and its variance (or data to calculate the variance), or genotype frequency among participants with and without MetS. All potentially relevant publications were retrieved and evaluated for inclusion. References of all relevant publications were also hand searched for additional studies missed by the database search. Only studies published in the English language were included. Two authors (Haina Wang and Jingyun Yang) performed the search independently. Disagreement over eligibility of a study was resolved by the evaluation of a third reviewer (Shuqian Dong) until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the following data according to a pre-specified protocol: first author’s name, year of publication, country of origin, name of the study cohorts, study population characteristics (sample size, age, sex, and prevalence of metabolic syndrome), definition of metabolic syndrome, genetic models (additive, dominant, recessive or allelic) used for association study, genotype frequency among participants with and without MetS, or OR and its variance (or data for calculation of the variance) of having metabolic syndrome and confounding factors controlled for. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Extracted data were entered into a computerized spreadsheet for analyses.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratio was used as a measure of the association of the genetic variants in FTO with MetS. ORs were used as provided in the papers; otherwise, they were calculated from genotype frequency data. ORs were logarithmically transformed to normalize the distributions and standard errors were derived from the confidence intervals (CI) reported in each study. We used random-effects models to calculate OR and the corresponding 95% CI. The Z-test was used to calculate the P value of the overall effect for the meta-analysis. We used forest plot to graphically present the calculated pooled OR and its 95% CI. Each study was represented by a square in the plot, the area of which is proportional to the weight of the study. In the random-effects model, we used the inverse of the variance of each study as the weight for the study. The overall effect from meta-analysis is represented by a diamond, the width of which represents the 95% CI for the estimate. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using Q statistics. We consider studies to be homogeneous if P > 0.1 since Q statistics is under powered. Publication bias was assessed visually using a funnel plot and tested with Egger’s regression test [38].

In order to assess the overall association of FTO with MetS, we conducted a gene-based analysis using the reported P values of the association of genetic variants in FTO with MetS and the P values from our meta-analysis. This association was assessed using four popular P value combination methods: the Fisher’s method [39], the Simes method [40], the modified inverse normal method [41], and the truncated product method (TPM) [42]. For a detailed description of the four methods, see Supplementary materials. Because the P values of the association of individual SNPs within FTO with MetS are most likely to be dependent, we used 100,000 simulations to estimate the P value for TPM.

Meta-analysis was performed using Stata 11.2 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX). All the other analyses were performed using Matlab 7.10.0.499 (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).

Results

Literature search and eligible studies

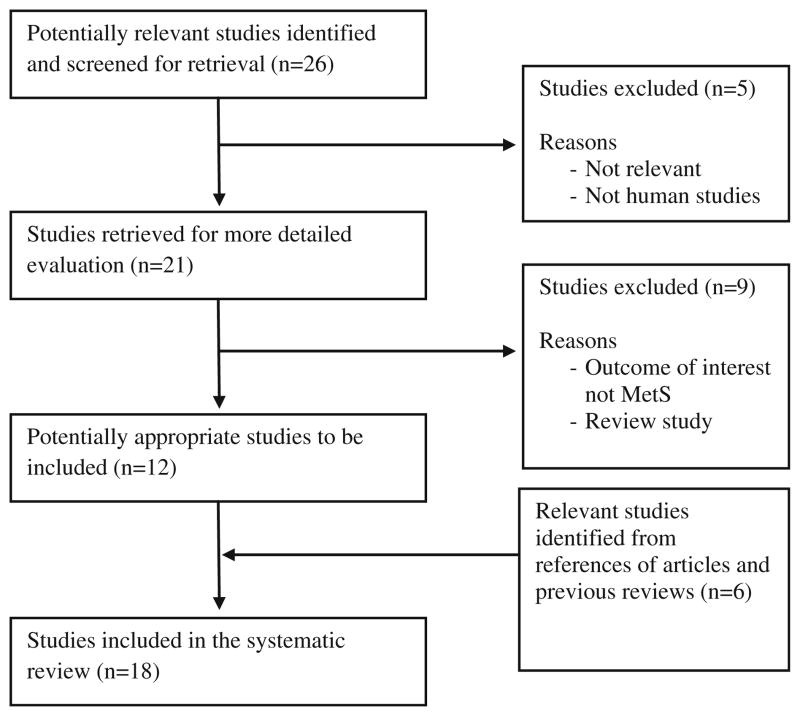

Figure 1 is the flow diagram showing the process of selection of studies included in our analysis. Using our pre-defined search strategy, we identified a total of 26 potential studies through our initial search. After screening of the abstract of these studies, five were excluded either because they were irrelevant or the studies were not about human subjects. The remaining 21 studies were retrieved for more detailed evaluations, which excluded an additional nine studies because the outcome of interest is not MetS or a review study, leaving 12 potentially relevant studies to be included in our analysis. A further review of the references of these studies and review papers identified six more studies. A total of 18 studies from 13 papers met the eligibility criteria and were included in our analyses [26–31, 33–37, 43, 44].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review

All included studies were published since 2008 and had sample size ranging from 236 to 21,674 participants. Prevalence of MetS ranged from 7 to 81% (Table 1). Of these 18 studies, 14 studies reported association results for rs9939609, four studies for rs8050136 and rs1421085. They were included in the corresponding meta-analysis for each of the three SNPs. The combined study population included 33,543 participants in the meta-analysis of rs9939609, 25,801 of rs8050136, and 2,467 of rs1421085. In addition to these three SNPs, Wang et al. [33], Hotta et al. [30], and Steemburgo et al. [36] reported genetic association of ten other SNPs in FTO with MetS. Their results, together with our meta-analysis results, were included in our gene-based analysis.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of all studies

| Study name, author, and publication year | Study population | Definition of metabolic syndrome | Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (%) | Model used for genetic association | Controlled variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIAMI Ranjith et al. 2011 [37] | 485 men and women aged ≤ 45 in South Africa | ATP III | 61 | Additive | – |

| CRISPS Cheung et al. 2011 [35] | 2,214 men and women mean age 46 in Hong Kong | Modified IDF | 37 | Additive | Age, sex |

| PUMCH Wang et al. 2010 [33] | 236 men and women aged 47–55 in China | IDF | 46 | Allelic | – |

| CLH Attaoua et al. 2009 [43] | 247 women mean age 39 in France | ATP III | 27 | Dominant | – |

| MPP Sjögren et al. 2008 [27] | 16,143 men and women mean age 46 in Swedish | Self-defined, similar to ATP III | 7 | Additive | Age, follow up time and sex |

| WPOS Attaoua et al. 2008 [28] | 307 women mean age 28 in central Europe | ATP III | 24 | Dominant | – |

| NFBC1996 Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 4,423 men and women mean age 31 in Finland | ATP III | 7 | Additive | – |

| Oxford Biobank Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 1,149 men and women mean age 42 in UK | ATP III | 15 | Additive | – |

| Caerphilly Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 1,046 men and women mean age 56 in UK | ATP III | 21 | Additive | – |

| UK T2D GCC controls Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 1,858 men and women mean age 60 in UK | ATP III | 16 | Additive | – |

| BWHHS Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 3,191 men and women mean age 69 in UK | ATP III | 45 | Additive | – |

| InCHIANTI Freathy et al. 2008 [34] | 888 men and women mean age 71 in Italy | ATP III | 28 | Additive | – |

| NCME Al-Attar et al. 2008 [29] | 2,121 men and women aged ≥ 18 in Canada | ATP III | 15 | Dominant | – |

| EBM Hotta et al. 2011 [30] | 1,677 men and women mean age 52 | JCDCMS [6] | 35 | Additive | Age, gender |

| UFRG Steemburgo 2011 [36] | 236 men and women mean age 60 | IDF | 81 | Dominant | – |

| CMN Cruz et al. 2010 [26] | 936 men and women mean age 44 | AHA/NHLBI [7] | 42 | Allelic | – |

| DUMC Ahmad et al. 2010 [44] | 21,674 women mean age 52 | ATP III | 23 | Dominant | – |

| ETL Liem et al. 2010 [31] | 1,275 men and women mean age 16 | IDF | 69 | Additive | – |

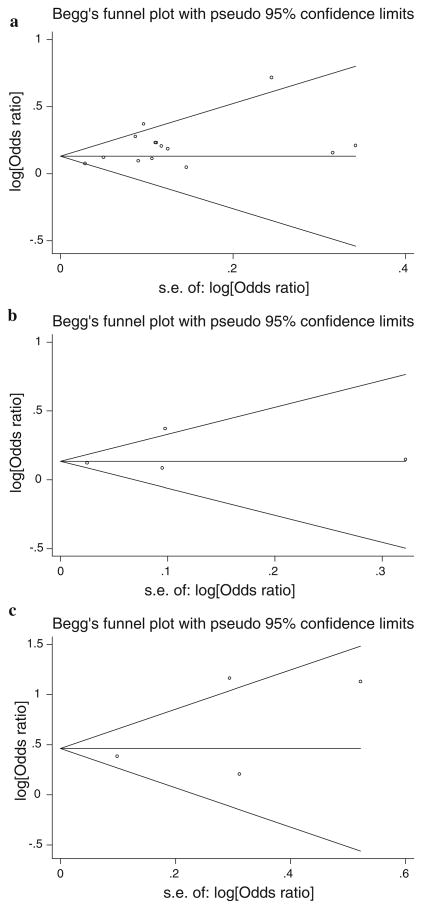

Assessment of publication bias

Both funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to assess publication bias (Fig. 2a–c). The funnel plot for rs9939609 seems asymmetrical, suggesting evidence of publication bias. Egger’s test shows some publication bias (t = 2.83, 95% CI 0.30–2.31; P = 0.015). No publication bias was detected for the meta-analysis of rs8050136 (t = 0.69, 95% CI −4.35–6.02; P = 0.561), and rs1421085 (t = 1.12, 95% CI −4.57–7.78; P = 0.38).

Fig. 2.

a Funnel plot for meta-analysis of rs9939609. b Funnel plot for meta-analysis of rs8050136. c Funnel plot for meta-analysis of rs1421085

Association of individual SNPs with MetS

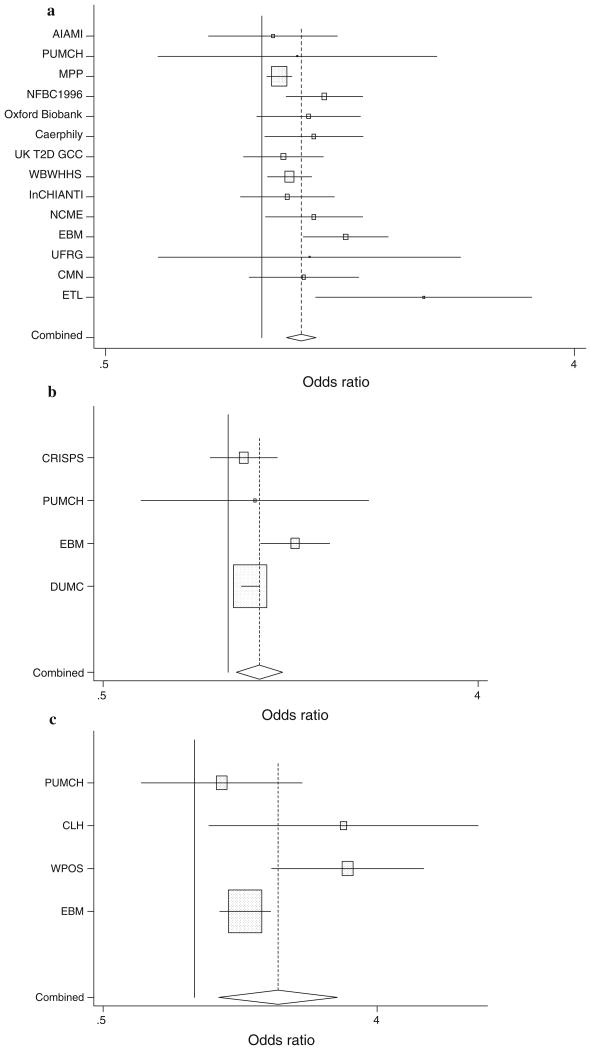

Fourteen studies provided results on association of rs9939609 with MetS. Random-effects meta-analysis gives an estimated OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.12–1.27; P = 1.38 × 10−7), indicating a strong association of the SNP with MetS (Fig. 3a; Table 2a). There was modest between-study heterogeneity (Q = 21.35, P = 0.066).

Fig. 3.

a Odds ratios of rs9939609 with metabolic syndrome. The horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. b Odds ratios of rs8050136 with metabolic syndrome. The horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. c Odds ratios of rs1421085 with metabolic syndrome. The horizontal bars represent the 95% confidence intervals

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the association of (a) rs9939609, (b) rs8050136, and (c) rs1421085 with metabolic syndrome

| Study | Weights | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) rs9939609 | |||

| AIAMI | 38.39 | 1.05 (0.79–1.40) | 0.74 |

| PUMCH | 9.59 | 1.17 (0.63–2.17) | 0.62 |

| MPP | 180.42 | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.007 |

| NFBC1996 | 81.46 | 1.32 (1.11–1.56) | 0.001 |

| Oxford Biobank | 54.30 | 1.23 (0.98–1.55) | 0.076 |

| Caerphilly | 58.69 | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | 0.04 |

| UK T2D GCC | 77.72 | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 0.29 |

| BWHHS | 138.50 | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | 0.018 |

| InCHIANTI | 62.42 | 1.12 (0.91–1.38) | 0.29 |

| NCME | 59.37 | 1.26 (1.02–1.56) | 0.03 |

| EBM | 71.42 | 1.45 (1.20–1.75) | 1.1 × 10−4 |

| UFRG | 8.22 | 1.24 (0.63–2.42) | 0.54 |

| CMN | 49.64 | 1.21 (0.94–1.52) | 0.13 |

| ETL | 15.51 | 2.05 (1.27–3.31) | 0.003 |

| Total | – | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 1.38 × 10−7 |

| (b) rs8050136 | |||

| CRISPS | 57.93 | 1.09 (0.91–1.32) | 0.36 |

| PUMCH | 8.94 | 1.16 (0.62–2.19) | 0.64 |

| EBM | 56.16 | 1.45 (1.20–1.76) | 1.4 × 10−4 |

| DUMC | 112.72 | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | 7.8 × 10−7 |

| Total | – | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 0.008 |

| (c) rs1421085 | |||

| PUMCH | 4.46 | 1.23 (0.67–2.26) | 0.50 |

| CLH | 2.50 | 3.10 (1.12–8.62) | 0.03 |

| WPOS | 4.68 | 3.20 (1.80–5.69) | 7.4 × 10−5 |

| EBM | 7.30 | 1.47 (1.21–1.78) | 9.1 × 10−5 |

| Total | – | 1.89 (1.20–2.96) | 0.006 |

Four studies provided results on association of rs8050136 with MetS. Random-effects meta-analysis gives an estimated OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.05–1.35; P = 0.008), indicating significant association with MetS (Fig. 3b; Table 2b). There was modest between-study heterogeneity (Q = 6.395, P = 0.09).

Four studies provided results on association of rs1421085 with MetS. Random-effects meta-analysis gives an estimated OR of 1.89 (95% CI 1.20–2.96; P = 0.006), indicating significant association with MetS (Fig. 3c; Table 2c). There was significant between-study heterogeneity (Q = 8.610, P = 0.035).

In addition to the above three SNPs, Wang et al. [33], Hotta et al. [30], and Steemburgo et al. [36] reported association of ten other SNPs in FTO with MetS. Their estimates, together with the meta-analysis results obtained from this study, were summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association of individual SNPs in FTO metabolic syndromea

| SNP | Chrom. position | Risk allele | OR (95% CI) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs8047395 | 52356024 | G | 1.64 (1.11–2.42) | 0.013 |

| rs8044769 | 52396636 | A | 1.63 (1.10–2.41) | 0.014 |

| rs8053740 | 52433213 | G | 1.51 (1.04–2.17) | 0.028 |

| rs17817288 | 52365265 | A | 1.47 (1.00–2.16) | 0.050 |

| rs1421085 | 52358455 | G | 1.89 (1.20–2.96) | 0.006 |

| rs9939609 | 52378028 | A | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 1.38 × 10−7 |

| rs8050136 | 52373776 | A | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 0.008 |

| rs17817449 | 52370868 | C | 1.16 (0.61–2.22) | 0.65 |

| rs9930506 | 52387966 | G | 0.92 (0.56–1.54) | 0.75 |

| rs6499640 | 52327178 | A | 1.11 (0.89–1.37) | 0.34 |

| rs1121980 | 52366748 | A | 1.32 (1.10–1.58) | 0.003 |

| rs1558902 | 52361075 | A | 1.47 (1.22–1.78) | 6.39 × 10−5 |

| rs7204609 | 52391106 | C | 4.36 (1.01–18.90) | 0.049 |

Gene-based analysis

Using the P valued obtained from association of individual SNPs with MetS, we performed a gene-based association study to examine the cumulative association of these genetic variants with MetS. All the four methods indicated strong association of FTO with MetS (all P < 10−5, Table 4). Additionally, we examined whether the observed association between FTO and MetS was driven by rs9939609, which was widely reported to have strong association with obesity and MetS. After removing this SNP, the gene-based association was attenuated, but remained statistically significant (Table 4). Another SNP, rs1558902, also showed significant association with MetS (P = 6.39 × 10−5). Further excluding this SNP in the gene-based analysis did not change dramatically the results. Thus, the observed association of FTO with MetS is unlikely dominated by these two SNPs.

Table 4.

Gene-based analysis of genetic variants in FTO with metabolic syndrome

| Fisher | Simes | Inverse | TPM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTO | 1.88 × 10−14 | 1.79 × 10−6 | 3.09 × 10−21 | <10−5 |

| FTOa | 1.06 × 10−9 | 7.67 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−15 | <10−5 |

| FTOb | 3.83 × 10−7 | 2.93 × 10−2 | 3.94 × 10−12 | <10−5 |

Excluding rs9939609

Further excluding rs1558902

Discussion

In this paper, we did a systematic literature search of studies on the association of genetic variants in FTO with MetS. Our meta-analysis confirmed the association of three SNPs in FTO with MetS. Gene-based analysis indicates that FTO is strongly associated with MetS and this association is not dominated by rs9939609, a SNP that was widely reported to have strong association with obesity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association of FTO with MetS through a gene-based approach.

The SNP rs9939609 is a common genetic variant in FTO that has been frequently reported to be associated with obesity [17, 22, 23, 45, 46] and in many studies with MetS [27, 29–31, 34]. A study by Freathy et al. [34] reported that data from Oxford Biobank [47], UK T2D GCC controls [32], and InCHIANTI [48] yielded insignificant association with MetS. A meta-analysis involving 12,555 participants reported an OR of 1.17 (95% CI 1.10–1.25, P = 3 × 10−6) [34]. Our meta-analysis involving 33,543 participants yielded a very similar OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.12–1.27). Our study thus provided updated meta-analysis and confirmed the strong association of this SNP with MetS (P = 1.38 × 10−7; Table 2a). Different from previous studies, our meta-analysis found a significant association of rs8050136 with MetS (Table 2b) with an OR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.05–1.35; P = 0.008) [33, 35]. Inconsistent results were also reported for rs10421085 [28, 30, 33, 43]. Our combined analysis yielded OR of 1.89 (95% CI 1.20–2.96) for rs10421085, indicating a significant association of the SNP with MetS (P = 0.006; Table 2c).

It is well known that for complex disorders, individual SNPs often exhibit modest association [49]. However, the combination of multiple genetic variants may have a larger effect which could be missed by SNP-based analysis that focuses only on most significant SNPs [50]. In this study, except rs9939609 and rs1558902, which show the strongest association (both P < 10−4), other SNPs show much less significant to insignificant association with MetS (Table 3). The gene-based analysis indicates a strong association of FTO with MetS, and this association is not driven by rs9939609 and rs1558902 (Table 4), implying that the gene-based analysis successfully captures the cumulative effects conferred by individual SNPs. This distinguished our study from most previous studies which focused only on individual SNPs in exploring the association with MetS [27–29, 33–35, 37, 43].

There are some limitations to our study. First, different genetic models were used in testing the genetic association (Table 1). One of our assumptions for the analysis is that different models should yield similar estimation of the association with MetS, which might not be held in practice. Second, we could only perform meta-analysis for three SNPs out of the 13 SNPs covered in this paper. The associations of the remaining ten SNPs were based on individual studies which might not have a large sample size. Further studies are needed to validate the association of these individual SNPs with MetS. Third, definition of MetS is not consistent across the 18 studies covered in the meta-analysis. Furthermore, different variables were controlled in the genetic association studies considered in this paper (Table 1).

In summary, we confirmed strong association of rs9939609, rs8050136, and rs10421085 in FTO with MetS by meta-analysis. The gene FTO is strongly associated with MetS. These results provide updated evidence that FTO gene may play a critical role in leading to MetS and targeting this gene may provide novel therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Independent Innovation Foundation of Shandong University (No. 2010TS071). The project described was supported by Award Number P50DA010075-15 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11033-011-1377-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Haina Wang, College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

Shuqian Dong, Department of Ophthalmology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China.

Hui Xu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Second Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

Jun Qian, Department of Orthopedics, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, CAMS & PUMC, Beijing, China.

Jingyun Yang, Email: jxy174@psu.edu, Methodology Center, Pennsylvania State University, 204 E. Calder Way, Suite 400, State College, PA 16801, USA.

References

- 1.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e13–e18. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults . Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. International Diabetes Federation; Brussels: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO consultation. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications; pp. 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuzawa Y. Metabolic syndrome—definition and diagnostic criteria in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12:301. doi: 10.5551/jat.12.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moebus S, Hanisch JU, Neuhauser M, et al. Assessing the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome according to NCEP ATP III in Germany: feasibility and quality aspects of a two step approach in 1550 randomly selected primary health care practices. Ger Med Sci. 2006;4:Doc07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zabaneh D, Balding DJ. A genome-wide association study of the metabolic syndrome in Indian Asian men. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollex RL, Hanley AJ, Zinman B, et al. Metabolic syndrome in aboriginal Canadians: prevalence and genetic associations. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez ML, Ruiz R, Gonzalez MA, et al. Association of NOS3 gene with metabolic syndrome in hypertensive patients. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:413–418. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guettier JM, Georgopoulos A, Tsai MY, et al. Polymorphisms in the fatty acid-binding protein 2 and apolipoprotein C-III genes are associated with the metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia in a South Indian population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1705–1711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamid YH, Rose CS, Urhammer SA, et al. Variations of the interleukin-6 promoter are associated with features of the metabolic syndrome in Caucasian Danes. Diabetologia. 2005;48:251–260. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YJ, Tsai JC. ACE gene insertion/deletion polymorphism associated with 1998 World Health Organization definition of metabolic syndrome in Chinese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1002–1008. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerken T, Girard CA, Tung YC, et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science. 2007;318:1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1151710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karasawa S, Daimon M, Sasaki S, et al. Association of the common fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) gene polymorphism with obesity in a Japanese population. Endocr J. 2010;57:293–301. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k09e-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha SW, Choi SM, Kim KS, et al. Replication of genetic effects of FTO polymorphisms on BMI in a Korean population. Obesity. 2008;16:2187–2189. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubacek JA, Bohuslavova R, Kuthanova L, et al. The FTO gene and obesity in a large Eastern European population sample: the HAPIEE study. Obesity. 2008;16:2764–2766. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng MC, Park KS, Oh B, et al. Implication of genetic variants near TCF7L2, SLC30A8, HHEX, CDKAL1, CDKN2A/B, IGF2BP2, and FTO in type 2 diabetes and obesity in 6, 719 Asians. Diabetes. 2008;57:2226–2233. doi: 10.2337/db07-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rong R, Hanson RL, Ortiz D, et al. Association analysis of variation in/near FTO, CDKAL1, SLC30A8, HHEX, EXT2, IGF2BP2, LOC387761, and CDKN2B with type 2 diabetes and related quantitative traits in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2009;58:478–488. doi: 10.2337/db08-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wing MR, Ziegler J, Langefeld CD, et al. Analysis of FTO gene variants with measures of obesity and glucose homeostasis in the IRAS family study. Hum Genet. 2009;125:615–626. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0656-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villalobos-Comparan M, Teresa Flores-Dorantes M, Teresa Villarreal-Molina M, et al. The FTO gene is associated with adulthood obesity in the Mexican population. Obesity. 2008;16:2296–2301. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horikoshi M, Hara K, Ito C, et al. Variations in the HHEX gene are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2461–2466. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz M, Valladares-Salgado A, Garcia-Mena J, et al. Candidate gene association study conditioning on individual ancestry in patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome from Mexico City. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:261–270. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjogren M, Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, et al. The search for putative unifying genetic factors for components of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2242–2251. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Attaoua R, Ait El Mkadem S, Radian S, et al. FTO gene associates to metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Attar SA, Pollex RL, Ban MR, et al. Association between the FTO rs9939609 polymorphism and the metabolic syndrome in a non-Caucasian multi-ethnic sample. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotta K, Kitamoto T, Kitamoto A, et al. Association of variations in the FTO, SCG3 and MTMR9 genes with metabolic syndrome in a Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2011;59(6):647–651. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liem ET, Vonk JM, Sauer PJ, et al. Influence of common variants near INSIG2, in FTO, and near MC4R genes on overweight and the metabolic profile in adolescence: the TRAILS (TRacking adolescents’ individual lives survey) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:321–328. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeggini E, Weedon MN, Lindgren CM, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang T, Huang Y, Xiao XH, et al. The association between common genetic variation in the FTO gene and metabolic syndrome in Han Chinese. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1852–1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freathy RM, Timpson NJ, Lawlor DA, et al. Common variation in the FTO gene alters diabetes-related metabolic traits to the extent expected given its effect on BMI. Diabetes. 2008;57:1419–1426. doi: 10.2337/db07-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung CY, Tso AW, Cheung BM, et al. Genetic variants associated with persistent central obesity and the metabolic syndrome in a 12 year longitudinal study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:381–388. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steemburgo T, de Azevedo MJ, Gross JL, et al. The rs7204609 polymorphism in the fat mass and obesity-associated gene is positively associated with central obesity and micro albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes from Southern Brazil. J Ren Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranjith N, Pegoraro RJ, Shanmugam R. Obesity-associated genetic variants in young Asian Indians with the metabolic syndrome and myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011;22:25–30. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2010-036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers. 4. Oliver and Boyd; Edinburgh: 1932. p. xiii.p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simes RJ. An improved bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1986;73:751–754. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartung J. A note on combining dependent tests of significance. Biom J. 1999;41:849–855. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaykin DV, Zhivotovsky LA, Westfall PH, et al. Truncated product method for combining P values. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;22:170–185. doi: 10.1002/gepi.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Attaoua R, Ait El Mkadem S, Lautier C, et al. Association of the FTO gene with obesity and the metabolic syndrome is independent of the IRS-2 gene in the female population of Southern France. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmad T, Chasman DI, Mora S, et al. The fat-mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene, physical activity, and risk of incident cardiovascular events in white women. Am Heart J. 2010;160:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hotta K, Nakata Y, Matsuo T, et al. Variations in the FTO gene are associated with severe obesity in the Japanese. J Hum Genet. 2008;53:546–553. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0283-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song Y, You NC, Hsu YH, et al. FTO polymorphisms are associated with obesity but not diabetes risk in postmenopausal women. Obesity. 2008;16:2472–2480. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan GD, Neville MJ, Liverani E, et al. The in vivo effects of the Pro12Ala PPARgamma2 polymorphism on adipose tissue NEFA metabolism: the first use of the Oxford Biobank. Diabetologia. 2006;49:158–168. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lesnick TG, Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC, et al. A genomic pathway approach to a complex disease: axon guidance and Parkinson disease. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng G, Luo L, Siu H, et al. Gene and pathway-based second-wave analysis of genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:111–117. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.