Abstract

We have previously shown that AAV2 undergoes anterograde axonal transport in rat and non-human primate brain. We screened other AAV serotypes for axonal transport and found that AAV6 is transported almost exclusively in a retrograde direction and, like AAV2, it is also neuron-specific in rat brain. Our findings show that axonal transport of AAV is serotype-dependent and this has implications for gene therapy of neurological diseases such as Huntington’s disease.

Keywords: AAV2, AAV6, retrograde transport, Huntington’s disease

Introduction

Previously, we found that adeno-associated virus type-2 (AAV2) undergoes robust axonal anterograde transport when injected into either rat striatum1 or non-human primate (NHP) thalamus2. Injections of AAV2-glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) into rat striatum resulted in GDNF expression in multiple basal ganglia nuclei, including globus pallidus, entopeduncular nucleus, subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra pars reticulata. Similarly, injection of AAV2-GDNF or AAV2-green fluorescent protein (GFP) into primate thalamus resulted in broad GDNF and GFP expression in the cerebral cortex, including cingulate cortex, pre-frontal, pre-motor, primary and secondary somatosensory and motor areas of the cortex. In addition to the intense staining of individual neuronal cell bodies and cellular processes, GDNF staining was observed across multiple layers of the cortex with an intensity gradient that was highest in cortical Layers III and IV after thalamic delivery of AAV2-GDNF. Although weak retrograde transport of AAV2 up the sciatic nerve from neuromuscular terminals has been reported3, this phenomenon does not seem to be so in the brain. For example, GDNF is not observed in the cortex after delivery of AAV2-GDNF to the striatum even though cortical neurons project abundantly to the striatum1. This suggests that AAV2 is not retrogradely transported by corticostriatal neurons in the brain, but exhibits a very strong bias toward anterograde transport.

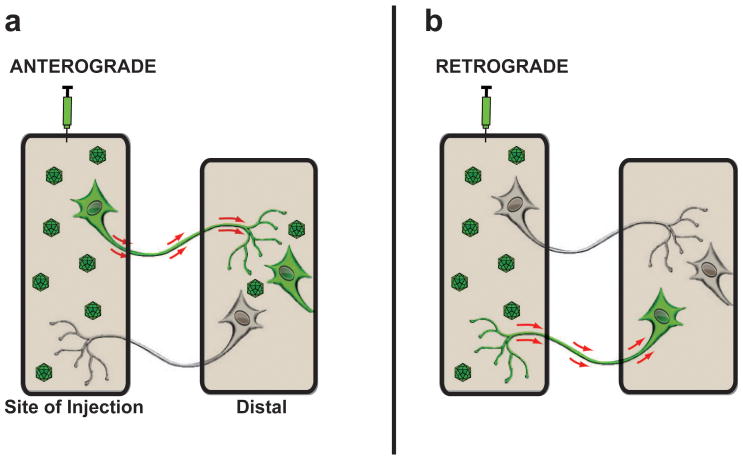

In assessing axonal transport of vectors it is important to recognize that transgenic proteins are often present at high levels in the cytoplasm of transduced neurons and, hence, neuronal fibers in distally innervated brain nuclei can be immunostained for the expressed protein. This phenomenon does not per se describe axonal transport; rather it is the presence of transduced cell bodies in non-injected areas of the brain that is indicative of potential axonal transport of the vector. Anterograde transport of intact virions is, therefore, characterized by the presence of transduced cell bodies in areas known to receive axonal projections from the site of vector delivery, but do not themselves have reciprocal projections to site of vector delivery. Thus, intact virions must be anterogradely transported along axons originating within the site of vector delivery, be released at the axon terminal, and then transduce neighboring cells2. Retrograde transport, on the other hand, requires uptake of vector by axonal projections within the site of delivery and transport to the distally located soma where it transduces the host cell nucleus and results in the presence of the transgenic protein throughout the neuron soma and fibers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Anterograde and Retrograde transport after AAV infusion.

Diagram illustrates anterograde and retrograde transport of AAV vectors from the site of delivery to a second distally located brain region. (a) Axonal anterograde transport requires the transport of viral particles via an axon projecting from the site of vector injection to a distal area with subsequent transduction of cells located within the brain region where the axon ends. The presence of fibers only in the distal area is not classified as anterograde transportation of the AAV vector. (b) Retrograde transport of AAV vectors occurs when viral particles are taken up by axonal terminals in the injection site and are then transported back to the neuronal cell soma where they subsequently transduce the neuron.

As part of our investigation into axonal transport of AAV vectors, we conducted a survey of a number of AAV serotypes. In order to avoid confounding effects, we eliminated AAV vectors that were not exclusively neuron-specific. Of an initial screen of six AAV serotypes (1, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9) in rat brain, only AAV6 was observed to be as neuron-specific as AAV2. Accordingly, we asked whether AAV6 underwent axonal transport similar to AAV2. To test this we examined the transport of AAV6 and AAV2 along efferent and afferent projections by infusing them into different regions of the rat brain. We found that AAV6 not only transduced rat neurons several-fold better than AAV2, but was also transported almost exclusively in a retrograde direction. We suggest that AAV6 may find particular utility in diseases, such as Huntington’s disease, where cortico-striatal pathways could be targeted. Identification of the molecular determinants of anterograde and retrograde axonal transport is likely to aid our understanding of mechanisms of axonal transport of AAV and assist in the engineering of novel AAV vectors with altered function.

Results

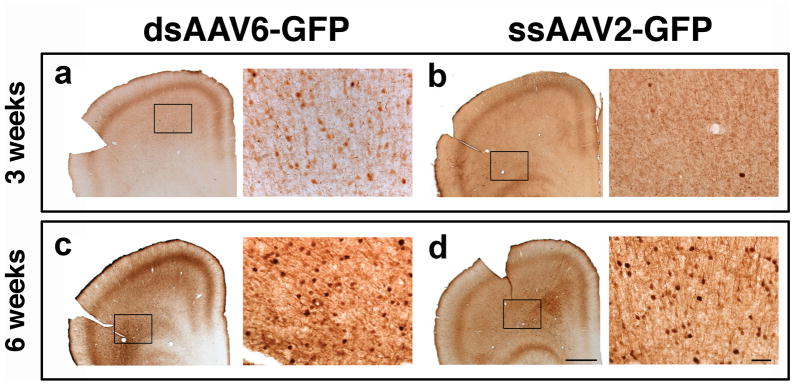

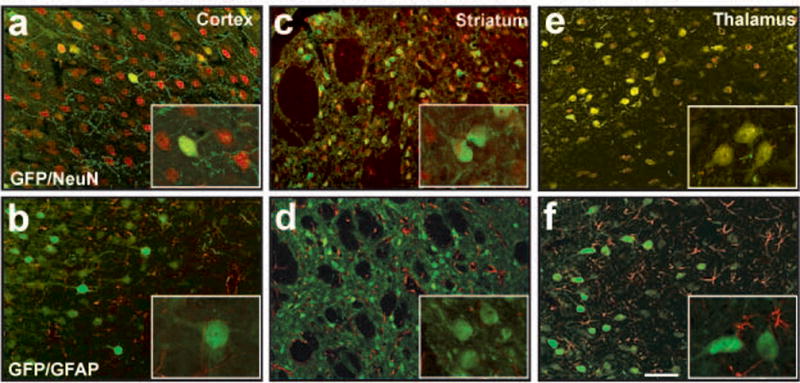

The central aim of this project was to understand differences in axonal trafficking of different AAV serotypes. We have previously documented that AAV2 is axonally transported in an anterograde direction in rodent and NHP brain1,2. In an initial screen, we looked for serotypes that transduced only neurons. We have previously made the observation that neuronal specificity offers protection against the problem of cell-mediated immunity arising from expression of non-native proteins in antigen-presenting cells in the brain4. Infusion of AAV6-GFP into rat thalamus demonstrated this serotype’s neuronal specificity (Fig. 2). The tropism of other serotypes generated a mixed pattern of cellular transduction with GFP+ glia and neurons found in regions proximal and distal to the site of injection (data not shown).

Figure 2. Cellular specificity of AAV6-GFP.

Neuron-specific transduction after parenchymal infusion of AAV6-GFP (a, c and e) with no transgene expression detected in glia within regions of the cortex (b), striatum (d) and/or thalamus (f). Inserts show high power magnification images of GFP+ cells. Scale bar 20 μm.

In previous experiments, we found that the double-stranded nature of the AAV6-GFP vector evinces more powerful transduction than the single-stranded AAV2-GFP (data not shown). Therefore, to roughly equalize GFP expression, we decided to compare a 15μL AAV2-GFP injection into the rat brain to a 3μL injection of AAV6-GFP.

Three weeks after unilateral injection of these two vectors we found robust GFP expression at the site of injection in all animals that were infused either in thalamus or in striatum (Supplementary Fig. S1, available online).

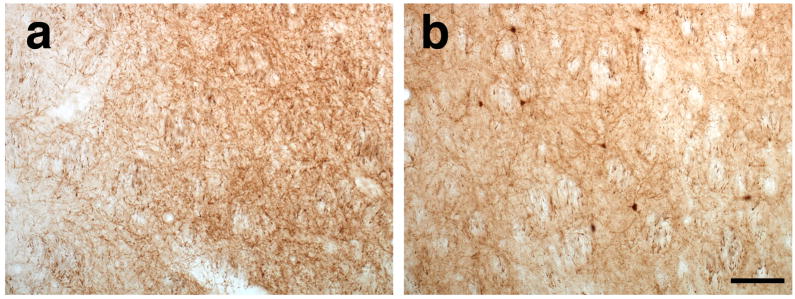

Thalamic infusion

To determine whether there were any differences in axonal transport, we injected AAV6-GFP and AAV2-GFP into the thalamus and analyzed transduction patterns 3 and 6 weeks after delivery. After 3 weeks, GFP+ neurons were only observed in the cortex of AAV6-GFP injected rats (Fig. 3a) but not in the cortex of those that received AAV2-GFP (Fig. 3b). We found GFP+ cells along the anterior-posterior axis of the brain from pre-frontal to occipital cortex, which excludes cannula reflux as an explanation (Supplementary Fig. S2, available online). In contrast, 6 weeks after thalamic infusion, GFP+ cells were observed after both AAV6-GFP and AAV2-GFP injection (Fig. 3c and 3d, respectively). These results suggest that transduction and axonal transport occur at a slower rate for AAV2 than AAV6. This difference in the time-course of distal but not proximal transduction is, in our view, consistent with the idea that transduction of distal neurons by anterograde transport should take considerably longer than retrograde transport, and is in agreement with previous data showing slow changes in transduction pattern in NHP after delivery of AAV2-human L-amino acid decarboxylase to the putamen 5.

Figure 3. Thalamo-cortical transport of AAV6 and AAV2.

GFP expression in neuronal cell bodies of the cortex 3 weeks after thalamic infusion was found only in AAV6-GFP animals (a), and not seen after AAV2-GFP delivery (b). Transduction of cortical cell bodies after AAV2-GFP infusion was detected 6 weeks after thalamic injection (c). Scale bar for low 500 μm and high magnification 10 μm.

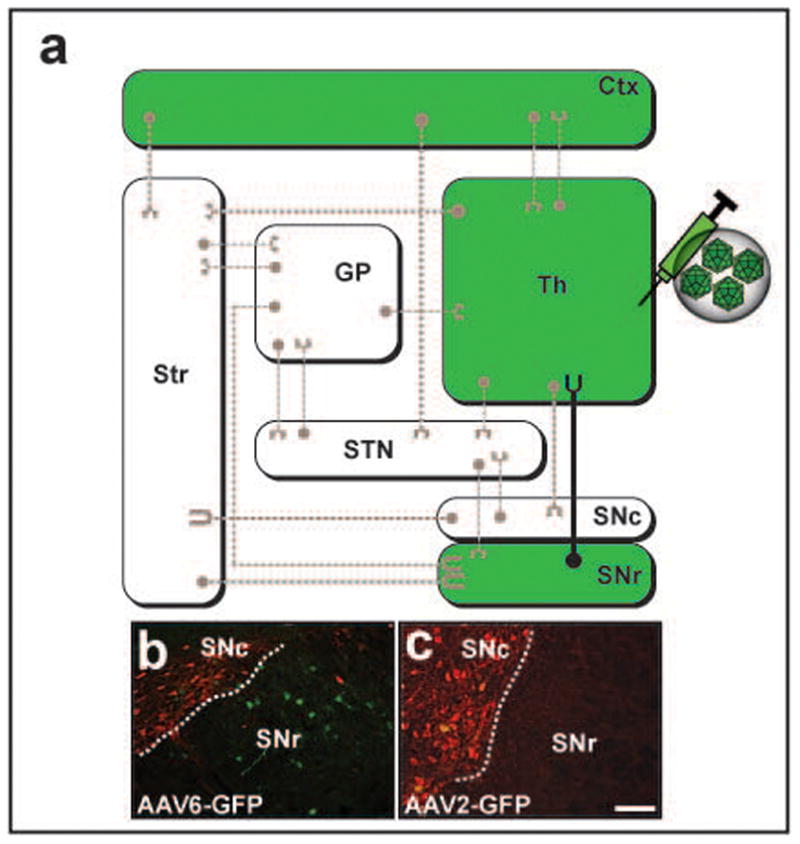

Clearly, transduction of thalamus is complicated by the bidirectional neuronal connections between thalamus and cortex (cortico-thalamic and thalamo-cortical projections, Fig. 4a). Therefore, to determine any differences in transport between these vectors we looked for simpler connections between thalamus and other brain regions such as substantia nigra and striatum. Nigro-thalamic projections are attractive because the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) sends projections to the thalamus6 (Fig. 4a). Injection of AAV6-GFP into thalamus resulted in significant cell body GFP+ staining in SNr (Fig. 4b) at 3 weeks after infusion. In contrast, thalamic AAV2-GFP gave no staining in SNr (Fig. 4c), indicating absence of retrograde transport of AAV2 but robust retrograde transport of AAV6. In addition, thalamo-striatal projections are also attractive to determine whether or not AAV6 undergoes anterograde transport (Fig. 4a). We found no GFP+ cells in the striatum of 6-week animals that received AAV6-GFP (Fig. 5a). On the other hand, in accord with the previous data observed in the thalamo-cortical projections, we found GFP+ cells in the striatum of the animals that received AAV2-GFP in the thalamus (Fig 5b), indicating absence of anterograde transport of AAV6 and a delayed anterograde trans-synaptic transport of AAV2.

Figure 4. Axonal transport of AAV6 and AAV2 after thalamic infusion.

(a) Wiring diagram of the most representative connections in the basal ganglia organization. To simplify the diagram, regions colored in white as well as dashed axonal projections were not analyzed in the present study, but their presence and connectivity to other regions is acknowledged. Regions in colored green represent GFP+ areas after thalamic infusion of AAV6-GFP. Comparative infusion of AAV6-GFP at 3 weeks and AAV2-GFP at 6 weeks into the thalamus region revealed the presence of GFP+ cell bodies within the substantia nigra pars reticulata only after AAV6-GFP administration (b); this was not observed in AAV2-GFP animals (c). Note that tyrosine hydroxylase staining (red) reveals the sharp demarcation between compacta and reticulata compartments of the substantia nigra. Str: striatum, GP: globus pallidus, STN: subthalamic nucleus, Ctx: cortex, Th: thalamus, SNc/r: substantia nigra pars compacta/reticulata. Scale bar 500 μm.

Figure 5. Thalamo-striatal projections corroborated the absence of anterograde transport of AAV6 vector 6 weeks after surgery.

Striatal analysis after thalamic AAV6 infusion reveals the absence of GFP+ cells (a) suggesting the lack of anterograde transport. In contrast, GFP-transduced cells were found in the striatum of animals that received AAV2 (b) demonstrating the anterograde transport of the vector. Scale bar 50 μm.

A few isolated cell bodies were found in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) after thalamic AAV2, suggesting perhaps that there maybe some anterograde connections from thalamus to SNc, but the presence of such afferents remains to be elucidated. Thus, the provenance of this minimal expression is unclear.

Striatal infusion

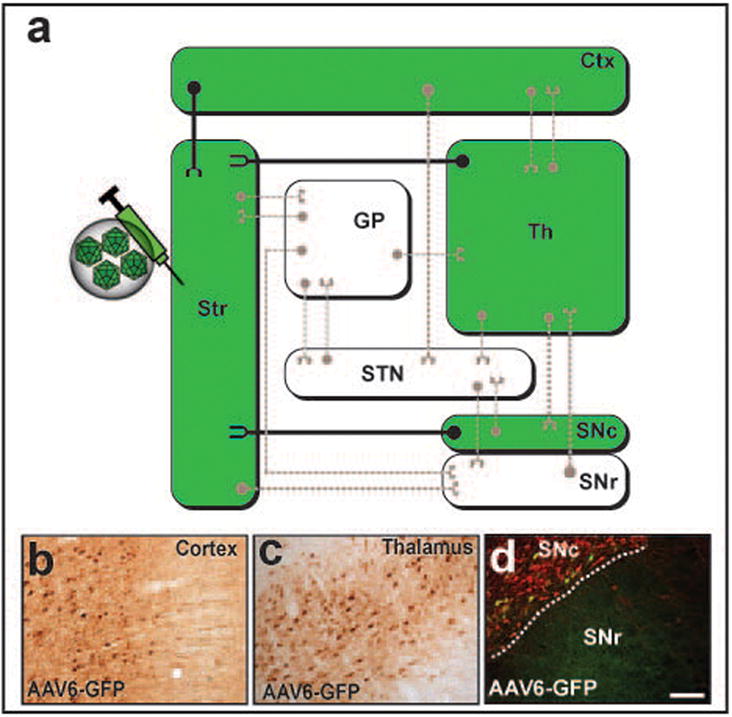

To further investigate the distribution pattern of AAV6 transduction, we injected AAV6-GFP into the striatum, a nucleus known to receive projections from many regions such as cortex, SNc or thalamus (Fig. 6a). Three weeks after striatal injection of AAV6-GFP, GFP+ neurons were found within the cortex, thalamus and SNc, indicative of transduction via retrograde transport of AAV6 (Fig. 6b–d, respectively). To examine the possible anterograde transport of AAV6, we analyzed the SNr, which receives projections from the striatum. After three weeks, no GFP+ cell bodies in the SNr were found (Fig. 6d). The complete absence of any positive cells, also suggests a lack of anterograde transport of AAV6-GFP, although the presence of GFP+ fibers shows that striatal GABAergic neurons were transduced.

Figure 6. Retrograde axonal transport of AAV6 after striatal infusion.

(a) Wiring diagram of the most representative connections in the basal ganglia organization. Transport of AAV6-GFP after striatal infusion is depicted in the diagram in green. Close examination of brain regions with known projections to the striatum demonstrated the presence of GFP+ cell bodies within the cortex (b), thalamus (c) and substantia nigra pars compacta (d, Green, GFP; Red, tyrosine hydroxylase), indicating a retrograde axonal transport of the vector through these projections. Note that green-colored regions in the diagram are representative of GFP+ cell bodies. Scale bar 500 μm.

Discussion

Anterograde transport of AAV vectors is characterized by the transduction of cells in a region of the brain that is not directly injected but receives axonal projections from neurons in the primary injection target (Fig. 1a). Inefficient internalization of AAV2 into the nucleus and the slow uncoating of the viral particles7 may facilitate anterograde transport of intact AAV2 particles to the terminals with subsequent release from axon terminals and/or trans-synaptic transport.

In contrast, retrograde transport of AAV is characterized by the transduction of neurons located in a brain region away from the site of injection, but that directly innervate the site of delivery (Fig. 1b). Uptake of AAV particles at the axon terminal may result in retrograde transport to the nucleus and transduction of the entire neuron.

In differentiating between anterograde and retrograde transport of AAV, we limited our analysis to GFP+ cell bodies in nuclei with well-characterized axonal connections (i. e., thalamus and striatum). Evidence of retrograde transport of AAV6 was demonstrable and contrasted strikingly with the anterograde pattern of AAV2. GFP+ cortical neurons observed in rats 6 weeks after thalamic infusion, but not after merely 3 weeks, would be the result of this anterograde transport of AAV2-GFP, as described above. Since the rat brain is a small structure, it is formally possible that infusing 15 μL of AAV2-GFP in the thalamus could result in some vector diffusion to the striatum. If so, the vector would enter some cortico-striatal terminals, retrogradely transport to the soma and transduce some cortical neurons. However, this is an unlikely possibility since thalamic infusion in our animals was well contained within the boundaries of the thalamus (Supplementary Fig. 2b, available online).

On the other hand, both striatal and thalamic infusions of AAV6-GFP resulted in the presence of GFP+ neurons in SNc, cortex and thalamus or SNr and cortex, respectively, indicating the retrograde transport of AAV6-GFP vector and subsequent transduction of distal structures that innervate these nuclei. In other words, examination of axonal nigro-thalamic and cortico-striatal projections provided a convincing argument for the retrograde transport of AAV6 along either striatal or thalamic connections. However, examination of thalamo-striatal and striato-nigral projections corroborated the absence of anterograde transport in AAV6 vector. AAV6 was not anterogradely transported either 3 or 6 weeks after infusion, as demonstrated by the lack of GFP+ cell bodies in brain nuclei innervated by either striatum or thalamus. These experiments permit the construction of a “wiring diagram” that describes axonal trafficking for each serotype after infusion into the thalamus (Fig. 4a) or striatum (Fig. 5a).

Little is known about the molecular mechanism of axonal transport of AAV although other viral vectors, such as herpes simplex 1, display both anterograde and retrograde axonal trafficking8 that seems to be dependent on specific protein motifs9. Similarly, retrograde transport of adenovirus has been described in rat brain10. It is unclear what drives the directionality of axonal AAV transport. One hypothesis is that differential engagement with molecular machinery that specifies anterograde or retrograde transport underlies this phenomenon. Herpes simplex virus 1 exhibits interactions with both kinesin and dynein to catalyze anterograde and retrograde axonal transport respectively11. We speculate that these two capacities may be separately defined in structural differences in AAV2 and AAV6 capsids12. The present study defines distinct functional specificities for AAV2 and AAV6 that may be amenable to mutational analysis. In addition, we reiterate the importance of vector production, purification method, overall quality and animal species-specificity as major determinants in AAV serotype tropism13–17.

Parenchymal retrograde axonal transport of AAV6 has some potential in neurological diseases with cortical involvement, such as Huntington’s disease18, since it could address gene therapy strategies designed to suppress mutant htt gene expression because both medium spiny neurons in striatum and cortico-striatal projections are affected in the disease. Delivery of an AAV6 vector with the appropriate transgene to the striatum would be expected to ameliorate the disease more effectively than would an AAV2 vector. We have recently developed an advanced MRI-guided delivery system for striatal gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease19 and the present study supports integration of AAV6 vectors with this delivery system for the treatment of Huntington’s disease and perhaps other diseases in which axonal transport may be a consideration.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Twenty-four Sprague-Dawley rats (~250–350 g) were randomly allocated into groups that received injections of AAV2-GFP (N = 12) or AAV6-GFP (N = 12) into either thalamus or striatum by convection-enhanced delivery as previously described1. All procedures were performed in accordance with the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vector

AAV2-GFP (single-stranded) and AAV6-GFP (double-stranded) were formulated at a concentration of 1.2 × 1013 vg/mL (AAV2) or 2.5 × 1013 vg/mL (AAV6) by the Vector Core at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. AAV6 titer was adjusted to ~1.2 × 1013 vg/mL prior to infusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.001% v/v Pluronic F-68.

Vector Infusion

Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, USA) and placed in a stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, USA). A 1-cm longitudinal incision was made in the skin overlaying the skull and a burr-hole was drilled at the following coordinates (thalamus, AP: −2.8, ML: +1.6, DV: −5.5 mm; striatum, AP: +1.2, ML: +2.4, DV: −5.0 mm). A cannula made from fused silica (Polymicro Technologies, USA) with a 1-mm step was used to deliver infusate unilaterally into the right thalamus or striatum by convection-enhanced delivery at a rate of 0.5 μL/min. All animals were infused with either 3 μL (AAV6-GFP) or 15 μL (AAV2-GFP) per target site (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Tissue Processing

Three or six weeks after vector infusion, animals were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS, their brains harvested and cryoprotected in 30% w/w sucrose. A sliding microtome (Thermo Scientific, HM 450) was used to cut 40-μm serial sections that were then processed for immunohistochemistry.

Immunoperoxidase Staining

A polyclonal antibody against GFP (rabbit anti-GFP, Millipore) was used for immunodetection of the transgene. Briefly, sections were washed with PBS (3 × 5 min), endogenous peroxidase activity quenched in 1% H2O2/30% ethanol for 30 min, and sections were then washed briefly in PBS/1% Tween (PBST). Sections were blocked in Background Sniper® (Biocare Medical, BS966G) for 30 min and incubated overnight at 4°C with GFP antibody (1:400) in Da Vinci® green diluent (Biocare Medical, PD900). After washing in PBST, sections were incubated for 1 h in Mach-3-rabbit-probe (Biocare Medical, RP531L) at room temperature (RT), washed again and incubated in Mach-3-rabbit-HRP polymer (Biocare Medical, RH531L) for 1 h at RT. After incubation, sections were washed in PBST and developed with DAB for 1 min (DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit, Vector Laboratories). DAB-processed sections were washed in PBS and mounted on frosted slides.

Immunofluorescent Staining

Double immunolabeling was performed to determine whether GFP+ cells were located within the SNc (tyrosine hydroxylase, TH+). Briefly, brain sections were immunostained for GFP (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100, Millipore) and TH (mouse monoclonal, 1:100, Millipore), washed with PBST, blocked for 60 min in 20% normal horse serum (Jackson Immuno Research) and incubated with primary antibodies in Biocare DaVinci® Green diluent (Biocare Medical, PD900) for 24 h at 4°C. After incubation with primary antibodies, sections were washed in PBST, incubated with a cocktail of secondary antibodies anti-rabbit-FITC (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and anti-mouse-TRITC (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBST for 1 h at RT, washed in PBS and wet-mounted on frosted-slides.

Supplementary Material

Coronal diagrams modified from the Paxinos and Watson atlas of the rat brain, represent the infusion coordinates used to target either the thalamus or striatum (red asterisk) demonstrate the transgene expression 3 weeks after infusion of AAV6-GFP (3 μL) or 6 weeks after AAV2-GFP administration (3 μL) into the thalamus (a–b) or the striatum with the same volume and survival time (c–d). Note robust transduction pattern for AAV6 compared to AAV2. Scale bar 500 μm.

Coronal diagrams in the left column correspond different antero-posterior levels of the rat brain as shown in the Paxinos and Watson rat atlas. Striatal infusion of AAV6-GFP resulted in a wide expression of GFP+ cell bodies found throughout the cortex extending from the pre-frontal to occipital cortical regions (a–h), distal from the site of injection (red asterisk). Scale bar 200 μm.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant R01NS073940 to KSB. No competing financial interest exists.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ciesielska A, Mittermeyer G, Hadaczek P, Kells AP, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS. Anterograde axonal transport of AAV2-GDNF in rat basal ganglia. Mol Ther. 2011;19:922–927. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kells AP, Hadaczek P, Yin D, Bringas J, Varenika V, Forsayeth J, et al. Efficient gene therapy-based method for the delivery of therapeutics to primate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2407–2411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810682106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaspar BK, Llado J, Sherkat N, Rothstein JD, Gage FH. Retrograde viral delivery of IGF-1 prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Science. 2003;301:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1086137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadaczek P, Forsayeth J, Mirek H, Munson K, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, et al. Transduction of nonhuman primate brain with adeno-associated virus serotype 1: vector trafficking and immune response. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:225–237. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daadi MM, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, Cunningham J, Forsayeth J, Eberling J, et al. Distribution of AAV2-hAADC-transduced cells after 3 years in Parkinsonian monkeys. Neuroreport. 2006;17:201–204. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000198952.38563.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kha HT, Finkelstein DI, Tomas D, Drago J, Pow DV, Horne MK. Projections from the substantia nigra pars reticulata to the motor thalamus of the rat: single axon reconstructions and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:20–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas CE, Storm TA, Huang Z, Kay MA. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol. 2004;78:3110–3122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3110-3122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frampton AR, Jr, Goins WF, Nakano K, Burton EA, Glorioso JC. HSV trafficking and development of gene therapy vectors with applications in the nervous system. Gene Ther. 2005;12:891–901. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGraw HM, Awasthi S, Wojcechowskyj JA, Friedman HM. Anterograde spread of herpes simplex virus type 1 requires glycoprotein E and glycoprotein I but not Us9. J Virol. 2009;83:8315–8326. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00633-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo H, Ingram DK, Crystal RG, Mastrangeli A. Retrograde transfer of replication deficient recombinant adenovirus vector in the central nervous system for tracing studies. Brain Res. 1995;705:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diefenbach RJ, Miranda-Saksena M, Douglas MW, Cunningham AL. Transport and egress of herpes simplex virus in neurons. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:35–51. doi: 10.1002/rmv.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, et al. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burger C, Gorbatyuk O, Velardo M, Peden C, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, et al. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2 and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2004;10:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi VW, McCarty DM, Samulski RJ. AAV hybrid serotypes: improved vectors for gene delivery. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:299–310. doi: 10.2174/1566523054064968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzsimons HL, Bland RJ, During MJ. Promoters and regulatory elements that improve adeno-associated virus transgene expression in the brain. Methods. 2002;28:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green AP, Huang JJ, Scott MO, Kierstead TD, Beaupre I, Gao GP, et al. A new scalable method for the purification of recombinant adenovirus vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1921–1934. doi: 10.1089/10430340260355338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Tatom JB, Henderson KM, Henning PP. AAV8, 9, Rh10, Rh43 vector gene transfer in the rat brain: effects of serotype, promoter and purification method. Mol Ther. 2008;16:89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berardelli A, Noth J, Thompson PD, Bollen EL, Curra A, Deuschl G, et al. Pathophysiology of chorea and bradykinesia in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14:398–403. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<398::aid-mds1003>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson RM, Kells AP, Rosenbluth KH, Salegio EA, Fiandaca MS, Larson PS, et al. Interventional MRI-guided Putaminal Delivery of AAV2-GDNF for a Planned Clinical Trial in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol Ther. 2011 doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Coronal diagrams modified from the Paxinos and Watson atlas of the rat brain, represent the infusion coordinates used to target either the thalamus or striatum (red asterisk) demonstrate the transgene expression 3 weeks after infusion of AAV6-GFP (3 μL) or 6 weeks after AAV2-GFP administration (3 μL) into the thalamus (a–b) or the striatum with the same volume and survival time (c–d). Note robust transduction pattern for AAV6 compared to AAV2. Scale bar 500 μm.

Coronal diagrams in the left column correspond different antero-posterior levels of the rat brain as shown in the Paxinos and Watson rat atlas. Striatal infusion of AAV6-GFP resulted in a wide expression of GFP+ cell bodies found throughout the cortex extending from the pre-frontal to occipital cortical regions (a–h), distal from the site of injection (red asterisk). Scale bar 200 μm.