Abstract

Background

Chronic heart failure (CHF) causes great suffering for both patients and their partners. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of an integrated dyad care program with education and psychosocial support to patients with CHF and their partners during a postdischarge period after acute deterioration of CHF.

Methods

One hundred fifty-five patient-caregiver dyads were randomized to usual care (n = 71) or a psychoeducation intervention (n = 84) delivered in 3 modules through nurse-led face-to-face counseling, computer-based education, and other written teaching materials to assist dyads to develop problem-solving skills. Follow-up assessments were completed after 3 and 12 months to assess perceived control, perceived health, depressive symptoms, self-care, and caregiver burden.

Results

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of dyads in the experimental and control groups were similar at baseline. Significant differences were observed in patients’ perceived control over the cardiac condition after 3 (P < .05) but not after 12 months, and no effect was seen for the caregivers. No group differences were observed over time in dyads’ health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms, patients’ self-care behaviors, and partners’ experiences of caregiver burden.

Conclusions

Integrated dyad care focusing on skill-building and problem-solving education and psychosocial support was effective in initially enhancing patients’ levels of perceived control. More frequent professional contact and ongoing skills training may be necessary to have a higher impact on dyad outcomes and warrants further research.

Keywords: Family, health-related quality of life, perceived control, self-care

Patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) and their partners form a large group in health care. The prevalence of symptomatic CHF is estimated at ~15 million individuals in greater Europe.1 In the United States, the estimated prevalence of CHF is 5.7 million. Chronic heart failure incidence approaches 10 per 1,000 people after the age of 65 years.2 The condition is a leading cause of hospitalization for elderly patients, and the prognosis is poor, with one-half of patients dying within 4 years after diagnosis.1

Partners have an important role in providing both practical and emotional support to patients with CHF.3,4 They provide assistance and psychosocial support for more hours than other family members owing to the strong emotional bonds that exist between them and the patient.5 High marital quality with sufficient emotional support influenced long-term survival3 and increased self-care of patients with CHF.6 Emotional reactions of burden, stress, decreased health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and depression have been found to be associated with the partner’s care-giving role.7,8 Health care mainly focuses on improving patient outcomes, but the awareness of the partners’ and families’ situation is increasing.9 Several studies have found that patients with CHF and their partners did not feel that they received sufficient support from health care professionals and had little understanding of the CHF condition, treatment, or prognosis.10,11 A strong relationship between health care professionals and patients as well as sufficient social support from an active social network has been shown to improve adherence to treatment.12 Even a single meeting to discuss self-care behaviors was found to stimulate important discussions between the dyads.13

Psychosocial support and patient-caregiver education, is rare in standard care despite recommendations in guidelines. It is recommended that family members be invited to participate in educational programs and decisions regarding treatment and care.1 Furthermore, there is a lack of research evaluating the effects of interventions that focus on patient-partner dyads in CHF. The specific aim of the present study was to design and evaluate the effects of an integrated dyad care program with education and psychosocial support on self-reported outcomes at 3 and 12 months after a hospital admission for acute CHF decompensation. Our hypothesis was that a care program that combines cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral therapy designed for patient-partner dyads can improve perceived control, self-care, and HRQOL and reduce symptoms of depression and caregiver burden.

Methods

Design and Setting

A randomized controlled design with follow-up assessment after 3 and 12 months was used to evaluate the effects of a 12-week intervention with education and psychosocial support delivered in 3 sessions to patient-partner dyads. The short-term follow-up after 3 months reflects the effects of the intervention soon after its termination, and the assessment at 12 months was used to measure the long-term effects of the intervention.

The setting was 1 university hospital and 1 county hospital in southeastern Sweden.

Sample

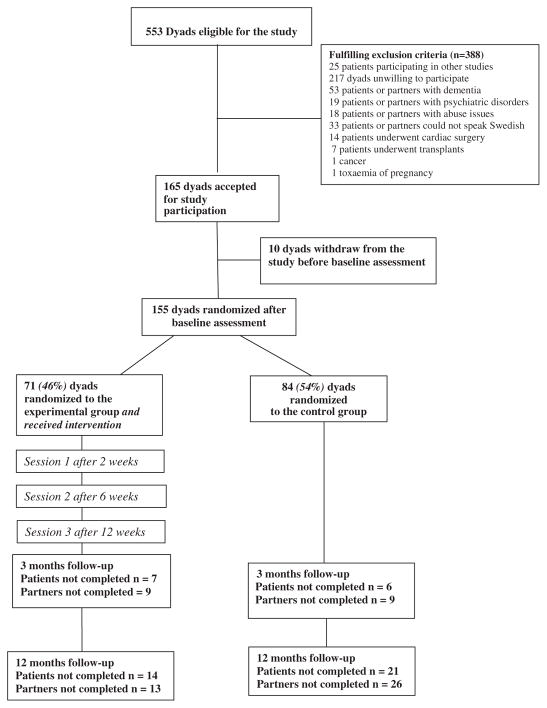

The sample included dyads consisting of a patient and a partner as being the informal caregiver. The inclusion criteria were to be a dyad consisting of a patient diagnosed with CHF based on the European Society of Cardiology guidelines,1 New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II–IV, with a partner living in the same household as the patient, recently discharged from hospital (ie, 2–3 weeks) after a CHF acute exacerbation. Exclusion criteria for the dyads were dementia or other severe psychiatric illnesses, drug abuse, difficulties in understanding or reading the Swedish language, undergoing cardiac surgery, including cardiac transplant, or participating in other studies. A flow chart illustrating the sample process is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating the dyads through the clinical study.

Procedures

The dyads were recruited from January 2005 to December 2008. Potential dyads included all patients hospitalized with CHF exacerbation at the Emergency Department and the Department of Cardiology at a university hospital and all hospitalized patients visiting a nurse-led CHF clinic at a county hospital. The dyads were initially informed verbally of the study through a telephone call or during a visit to the heart failure clinic. Potential patient-partner dyads who expressed an interest to take part in the study signed an informed consent and were given additional information related to the study and questionnaire-packages to complete in their own homes. Dyads that chose to participate returned the questionnaires by mail and were randomized to either the control or the experimental group. The randomization code was developed using a random-number table.

Ethical Issues

Throughout the study, the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki have been followed. Permission to carry out the study was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping. All dyads received verbal and written information about the study. Dyads that chose to participate gave written informed consent before engaging in the study. The dyads were assured of confidentiality and that a decision to withdraw from the study would not affect their future care.

Control Conditions

The dyads in the control group received care as usual, including traditional care in hospital and outpatient education and support. At present, this care is mainly focused on the patient’s needs.14,15 The partner is not systematically involved in the follow-up focusing on education and psychosocial support.

Experimental Conditions

In the experimental group, patients received usual care and treatment plus an integrated care intervention, including psychosocial support to maintain and strengthen the person’s physical and mental functions, knowledge, and perceived control to make them feel involved and reduce their stress and their partners’ burden.

The Intervention

The intervention in this study was based on a conceptual model developed by Stuifbergen et al.16 The concepts of Stuifbergen’s model have sprung from Pender’s model of health promotion17 and Bandura’s self-efficacy theory.18 Cognitive-behavioral strategies were chosen to assist dyads in recognizing and modifying factors that contribute to physical and emotional distress by changing thoughts and behaviors in a positive manner and assisting dyads in solving problems related to implementing strategies for self-care.

Shared care is a dyadic process based on the assumption that each participant affects and is affected by the other.19,20 Shared goals and a shared commitment to professional practice provide the essential building blocks of the dyad relationship. The dyad structure presents an opportunity for health care professionals to integrate their strengths and skills in a collaborative patient-partner centered effort.21

The intervention was delivered in 3 sessions through nurse-led face-to-face counseling, a computer-based CD-ROM program, and other written teaching materials. Education and psychosocial support have been found to be effective in improving patient outcomes.1 Computer-based education has been shown to be feasible, interactive, and effective in terms of improving knowledge in elderly patients with CHF.14

All sessions were conducted in the dyads’ homes or in the heart failure clinic, depending on the preference of the dyad. Each session lasted ≥60 minutes. The first session was conducted 2 weeks after discharge and the 2 remaining sessions occurred 6 and 12 weeks after discharge. The time window in which the sessions occurred was 1 week. The content of each session is presented in Table 1. Each session included education on CHF with booklets and computer-based education. The dyads were assisted by the nurse if necessary when working with the computer program. The intervention also included development of problem-solving skills to assist the dyads in recognizing and modifying factors that contribute to psychologic and emotional distress. The intervention focused on changing thoughts and behaviors and implementing strategies for self-care. The dialogue guide used during the sessions included an opportunity for the dyads to discuss their mutual and individual life situations, receive information, raise questions, discuss difficulties and subjects of joy, and deal with emotional and practical support and self-care. One important issue was the changing roles that arise and how to reduce the partner’s overprotection if needed, the dyad’s criticisms of each other, and the partner’s burden through support from the patient, the social network, and health care professionals. The dyads were also encouraged to talk about lifestyle changes, communication, and prospects and learning to live with lifelong CHF. The intervention covered a 12-week period, after which there was no reinforcement.

Table 1.

Content of Each of the 3 Modules Used in the Intervention

| Module 1 | Module 2 | Module 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive component | The circulatory system, definition of HF, medications, and symptom management | Lifestyle modifications: diet, smoking cessation, alcohol, immunization, regular exercise | Directing the care, relationship, and sexual activities; prognosis |

| Cognitive outcomes | Increased knowledge on the chronic HF syndrome and treatment |

Increased knowledge on the rationale for lifestyle changes | Increased knowledge on chronic HF care and outcomes |

| Support component | Introduce psychosocial support concept | Assess patient’s need of support Modify caregiver behavior |

Assess partner’s need of support Discuss partner’s burden |

| Support outcomes | Improved mental and physical functions | Strengthen self care behavior | Improved mutual support Decreased partner’s burden Improved control |

| Behavioral component | Intentions, abilities and self-efficacy regarding self-care | Barriers to lifestyle modifications | Strategies to improve or maintain self-care behavior |

| Behavioral outcomes | Daily weighing Monitoring of symptoms Flexible diuretic intake Adherence to medications |

Salt and fluid restriction Influenza and Pneumococcal immunizations Regular exercise |

Identifying life priorities and planning for the future |

| Teaching material | Booklet 1—basic level Flip chart |

Booklet 2—advanced level CD-ROM |

Booklet 2—advanced level CD-ROM |

Questionnaires

Permission to use, and instructions for scoring, each instrument was obtained from the appropriate publisher. Patients and partners completed separate questionnaire packages. All questionnaires were issued to both the patient and the partner except the European Self-Care Behavior Scale, which applied only to the patients, and the Caregiver Burden Scale, which applied only to the partners.

Demographic data including health history was collected using a self-administrated questionnaire identifying age, sex, education, habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, psychosocial support, and comorbidity. NYHA functional class was abstracted from independent physicians’ observations in the medical charts.

Short Form (SF)–36 is a generic 36-item scale that evaluates health in 8 dimensions. The dimensions are weighed together in 2 consecutive indexes: physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS). The physical part is made up of the dimensions of physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, and general health, and the mental part of the dimensions of vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. A higher score indicates better health.22 SF-36 is a well established and frequently used instrument and has been found to have good reliability and validity.23 In the present study, reliability estimates for both patients and partners were >0.70 in all dimensions (range 0.71–0.93).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory with each answer being scored on a scale value of 0–3. Higher total scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The cutoff scores used were: 0–13: no depression; 14–19: mild depression; 20–28: moderate depression; and 29–63: severe depression.24,25 The instrument has been validated in Swedish. The reliability coefficient alpha is >0.86.25 We experienced α = 0.92 in patients and α = 0.90 in the partners.

Control Attitude Scale (CAS) consists of 4 items: 2 about perceived control and 2 about helplessness. Furthermore, 2 of the items reflect the patient’s/partner’s own perceptions and 2 reflect the patients’ or partner’s perception about family members’ perceived control. Response statements are scored on a scale from 1 (none) to 7 (very much). The total score range is 4 to 28, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of perceived control.26 The psychometric testing for the Swedish translation has a reliability coefficient alpha of >0.80 for the patient version and 0.60–0.80 for the partner version.27 We experience alphas of ≥0.80 for both the patient and the partner versions.

European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale (EHFscBS) is a 12-item scale that uses a 5-point Likert scale between 1 (I completely agree) and 5 (I completely disagree) to measure self-care behaviors related to chronic HF. Overall score ranges from 12 to 60; lower scores indicate better self-care behavior. Reliability and validity have been found to be satisfying.28 Internal consistency reliability measured by Cronbach alpha was 0.72 in our study.

Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS) is a 22-item scale that measures caregiver burden as subjectively experienced by caregivers of chronically disabled persons. Responses were scored on a scale of 1–4 (not at all, seldom, sometimes, often). The total burden index is the mean of all 22 items; higher scores indicate greater burden. The total burden index CBS score can be divided into 3 groups; low burden (1.00–1.99), medium burden (2.00–2.99), and high burden (3.00–4.00).29,30 A previous study on reliability showed high internal consistency for 4 of the 5 factors, with Cronbach alpha values of 0.70–0.87; the only exception was the factor environment, which had an alpha of 0.53.29 We used the total score in the present study and experienced a Cronbach alpha value of 0.93.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the use of SPSS release 15.0 for Windows. Frequencies were run to determine the amount of missing data. Missing data was low at baseline (0.7%–8.1%), at 3 months it was up to 10.9%, and at 12 months it was up to 25%. Missing data on SF-36 were imputed by the mean of the sub-scale if only 1 item in a subscale was missing and in the EHFscBS with score 3 if <3 items were missing. Missing data in BDI-II were imputed by 0. Missing data in CBS and CAS were not replaced, because there are no recommendations for imputation from the constructors of these instruments. To examine the equality of the 2 groups, baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were compared with the use of chi-square or Student t tests depending on the level of measurement. Randomization ensured equal distribution between the 2 groups of potentially confounding characteristics. The effect of the intervention on each of the variables of interest was evaluated at the aggregate level by a Student t test to determine if the control and experimental groups had significantly different mean scores on all variables of interest at baseline and 3 and 12 months. The mean changed scores for the control and experimental groups were also compared by a Student t test. The categorization of comorbidity, BDI-II, and CBS for the control and experimental groups were compared by a chi-square test. The level for statistical significance was set to P < .05.

Results

A total of 155 dyads were included in the study and completed baseline assessment (Fig. 1). Clinical and demographic characteristics of the dyads are described in Tables 2 and 3. The majority of the patients were men and the majority of the partners women. NYHA functional class III was the dominant function class of the patients.

Table 2.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Patients

| Significance | Control (n = 84) | Intervention (n = 71) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 73 ± 10 | 69 ± 13 | ns |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 68 (80.9%) | 49 (69.1%) | ns |

| Female | 16 (19.1%) | 22 (30.9%) | ns |

| NYHA functional class | |||

| II | 25 (30%) | 25 (35%) | ns |

| III | 43 (51%) | 39 (55%) | ns |

| IV | 16 (19%) | 7 (10%) | ns |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 38 (45%) | 24 (34%) | ns |

| Hypertension | 26 (31%) | 27 (38%) | ns |

| Diabetes | 10 (12%) | 8 (11%) | ns |

| Stroke | 8 (10%) | 9 (13%) | ns |

| Lung disease | 7 (8%) | 3 (4%) | ns |

| Medication | |||

| ACEI/ARB | 76 (90%) | 65 (92%) | ns |

| β-Blockers | 74 (88%) | 62 (87%) | ns |

| Diuretics | 63 (75%) | 56 (79%) | ns |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Table 3.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Partners

| Control (n = 84) | Intervention (n = 71) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 70 ± 10 | 67 ± 12 | ns |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 16 (19.1%) | 22 (30.9%) | ns |

| Female | 68 (80.9%) | 49 (69.1%) | ns |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 13 (15%) | 8 (11%) | ns |

| Hypertension | 25 (30%) | 25 (35%) | ns |

| Diabetes | 4 (5%) | 7 (10%) | ns |

| Stroke | 4 (5%) | 3 (4%) | ns |

| Lung disease | 10 (12%) | 1 (1%) | <.05 |

The intervention lasted up to 12 weeks, and the follow-up evaluation presented in this study was carried out after 3 and 12 months. The patients had low control at baseline (16.0 in the intervention group and 18.0 in the control group), that improved to a moderate level during follow-up in both groups. Patients in the intervention group improved their levels of perceived control significantly more than control patients after 3 months (P < .05), but not after 12 months (Table 4). However, the same result was not found in the partners, whose perceived control remained unchanged in both the intervention group and the control group. There were no significant differences in HRQOL and symptoms of depression in dyads, self-care behavior in patients, and caregiver burden in the partners between the control and intervention groups after 3 and 12 months (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptoms of Depression in Patients and Partners, Self-Care in Patients, and Caregiver Burden in Partners at Baseline and at 3 and 12 months’ follow-up

| Total Score at Baseline | Difference Baseline–3 mo | P Value | Difference Baseline–12 mo | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients’ perceived control | |||||

| Control | 17.3 ± 4.6 | −0.4 ± 4.8 | .03 | −2.9 ± 4.8 | .79 |

| Intervention | 14.7 ± 5.5 | −2.2 ± 4.5 | −3.2 ± 5.4 | ||

| Partners’ perceived control | |||||

| Control | 16.1 ± 4.2 | −1.8 ± 10.0 | .60 | −1.7 ± 5.3 | .11 |

| Intervention | 15.7 ± 5.0 | −1.0 ± 4.7 | −4.0 ± 5.5 | ||

| Patients’ PCS | |||||

| Control | 31.8 ± 10.0 | −0.5 ± 6.4 | .99 | −0.5 ± 7.9 | .39 |

| Intervention | 33.6 ± 8.7 | −0.5 ± 7.6 | −1.9 ± 9.8 | ||

| Partners’ PCS | |||||

| Control | 44.4 ± 11.3 | 0.8 ± 6.9 | .74 | 3.18 ± 9.5 | .69 |

| Intervention | 48.7 ± 9.5 | 1.2 ± 6.6 | 3.81 ± 7.3 | ||

| Patients’ MCS | |||||

| Control | 42.2 ± 12.6 | −3.1 ± 12.5 | .10 | −4.22 ± 11.9 | .88 |

| Intervention | 39.9 ± 12.8 | 0.3 ± 8.8 | −4.55 ± 11.2 | ||

| Partners’ MCS | |||||

| Control | 46.0 ± 12.4 | −2.3 ± 9.3 | .44 | −1.8 ± 9.6 | .49 |

| Intervention | 46.4 ± 10.4 | −0.9 ± 9.6 | −3.1 ± 10.4 | ||

| Patients’ BDI-II | |||||

| Control | 9.7 ± 8.8 | 0.6 ± 10.8 | .17 | −0.4 ± 6.8 | .47 |

| Intervention | 11.7 ± 8.8 | 4.1 ± 9.3 | 0.7 ± 6.1 | ||

| Partners’ BDI-II | |||||

| Control | 7.7 ± 8.0 | −0.1 ± 3.2 | .54 | −0.45 ± 4.1 | .70 |

| Intervention | 6.5 ± 5.6 | −0.7 ± 5.4 | −1.1 ± 9.2 | ||

| Patients’ self-care behavior | |||||

| Control | 28.2 ± 8.4 | 2.0 ± 6.9 | .35 | 1.3 ± 6.9 | .64 |

| Intervention | 26.5 ± 7.8 | 3.1 ± 6.3 | 0.6 ± 8.2 | ||

| Partners’ caregiver burden | |||||

| Control | 1.7 ± 0.7 | −0.3 ± 6.6 | .25 | 0.2 ± 6.4 | .86 |

| Intervention | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 7.4 | −0.1 ± 8.5 | ||

PCS, SF-36 physical component scale; MCS, SF-36 mental component scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Negative mean difference values between baseline and 3 and 12 months indicate improved health-related quality of life and improved perceived control, less depressive symptoms, decreased self-care behavior, and caregiver burden. Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 5.

Distribution of the Categorization of Beck Depression Inventory II for Patients and Partners in the Control and Experimental Groups at Baseline and After 3 and 12 Months

| Baseline | 3 mo | 12 mo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partners | |||

| No depressive symptoms (score 0–13) | |||

| Control | 83% | 81% | 83% |

| Intervention | 89% | 85% | 80% |

| Minor depressive symptoms (score 14–19) | |||

| Control | 11% | 11% | 9% |

| Intervention | 8% | 13% | 12% |

| Moderate depressive symptoms (score 20–28) | |||

| Control | 2% | 6% | 4% |

| Intervention | 3% | 1% | 7% |

| Major depressive symptoms (score 29–63) | |||

| Control | 4% | 2% | 4% |

| Intervention | 0 | 1% | 1% |

| Patients | |||

| No depressive symptoms (score 0–13) | |||

| Control | 74% | 74% | 70% |

| Intervention | 67% | 67% | 60% |

| Minor depressive symptoms (score 14–19) | |||

| Control | 14% | 18% | 24% |

| Intervention | 15% | 20% | 25% |

| Moderate depressive symptoms (score 20–28) | |||

| Control | 8% | 4% | 2% |

| Intervention | 14% | 10% | 12% |

| Major depressive symptoms (score 29–63) | |||

| Control | 4% | 4% | 4% |

| Intervention | 4% | 4% | 3% |

There were no differences found between the groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first major randomized study to examine the effects of a theory-based intervention with education and psychosocial support for patients with CHF and their partners. Our main finding was that perceived control significantly improved in the patients at short-term follow up. This is an important outcome, because earlier studies have shown that a higher level of perceived control is important to reduce psychologic stress.31 Poor functional status of the caregiver, overall perception of caregiving distress, and low perceived control have been found to be associated with depressive symptoms in caregivers.32 The mean score of CAS in US patients recovering after myocardial infarction was 20.6.33 Scores <16 are considered to indicate low level of control.34 Our patients had low perceived control at baseline that improved to a moderate level during follow-up. However, as a result of the increased experience of control over their cardiac condition we did not find a direct improvement in the patients’ mental well-being; symptoms of depression did not decrease, and the mental dimension of HRQOL did not significantly improve. More frequent professional contact and ongoing skills training may be necessary to have a marked impact on dyad outcomes and warrants further research.

Earlier studies have shown that both patients and partners were worried, did not receive enough support, and reported an increased burden.7,8,11 Dyads affect each other regarding HRQOL and symptoms of depression.35 Partners experience more distress when the patient has more advanced end-stage CHF.36,37 There is a need for more qualitative research describing the needs of dyads to form new types of interventions in close collaboration with the dyads affected by heart failure.

Our hypothesis that education and psychosocial support for dyads will improve patients’ care has to some extent been investigated previously in a pilot study by Dunbar et al, who found that adherence to nonpharmacologic treatment in terms of dietary sodium intake was improved after a family intervention.38

The reason for the neutral effects of the intervention in the partners in our study may be that our group of patients, even though classified as a risk group owing to their NYHA functional status and recent hospitalization for CHF, were more stable than other populations investigated.36,37 Earlier studies with positive results of psychosocial and education interventions targeting patients have often included >50% of patients living on their own without a partner.39 It might be that even without the intervention the dyads found sufficient coping-strategies for supporting each other.2 Moreover, in comparison with other disease groups, there is a greater burden of caregiving in, eg, dementia and stroke patients40,41 than we found in our group of CHF partners.

Would there have been other outcomes more relevant to measure when evaluating the intervention? Perhaps we should have used a scale to measure self-efficacy, because this was part of the intervention. Furthermore, we did not assess the dyadic relationship or marital quality, which are other variables that might have affected the outcomes. A different choice could have been to use HRQOL instruments developed specifically for HF patients, such as the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. The instruments used (SF-36, BDI-II, CAS, EHFscBS, and CBS) have good validity and have often been used to evaluate similar interventions. To include more items might have increased the dropout rates owing to subject burden. Interviews would be an option for dyads to express themselves more in depth, but in a large randomized sample this methodology has limitations.

The present study has some limitations that need to be addressed. First, the data collection spanned almost 4 years. However, there were no big changes in diagnostic methods or treatment or other social reforms including CHF patients and their partners during the time period of data collection. Many patients with CHF either lacked a partner who could participate in the study or were too sick and tired to participate in the study, which suggests the potential for bias in the study sample with only 28% of those eligible randomized. This may affect the generalizability of the findings. However, as previously stated by Lamura et al, these difficulties to include dyads are not uncommon in studies of elderly patients and their partners.5 The high number of items in the questionnaire package can be exhausting for elderly patients to complete. It can be expected that the frailest dyads had the most problems during data collection, which may affect the generalizability of the results.

Second, the 3-month evaluation and the length of the intervention of 12 weeks were simultaneous, leaving little time for change to occur in a detectable manner. The 12-month follow up measure may have been too distant from the intervention to detect change. Therefore, it would have been beneficial to also have data from 6 months’ follow-up. Another limitation was that patients in the control group might have received education and psychosocial support that to some extent was based on the same principles as the intervention group, because they received care at a heart failure clinic and some partners may have been included in that care. However, the main difference was that partners in the intervention group were always actively involved as equals to the patient, because they were treated as a dyad. The intervention was built on a standardized theory-based model27 and adjusted based on the specific needs of each dyad. A heart failure nurse delivered the intervention. It may have been more beneficial to include a multidisciplinary team in the intervention including physiotherapists, psychologists or social workers, and physicians. The intervention should perhaps also have involved group sessions, giving the dyads an opportunity to share experiences with one another. Because dyad interventions in CHF patient-partner dyads are rare, we will use the experience from this study to design a new interventional study, and hopefully with a multicentered approach we can achieve a larger sample size.

Conclusion

The dyad care program focusing on the development of problem-solving skills to assist the dyads in managing CHF significantly improved the level of perceived control over the heart disease in the patient group during short-term follow up. In other aspects, such as physical and mental well-being, self-care, and caregiver burden experienced, the effects were limited in both patients and partners.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Grants from Linköping University, Swedish Research Council, Swedish Institute for Health Sciences, Heart and Lung Foundation, Heart and Lung Disease National Association, and Lions Research Foundation.

We thank Linköping University, the Swedish Institute for Health Science, the Swedish Research Council and the Health Sciences Centre for financial support. We also thank the partners and chronic HF patients who participated in the study, the secretaries at the Department of Cardiology and Emergency Department, especially Lotta Björk and Berit Anderson, and Annette Waldemar and Lillevi Nestor at the county hospital in Norrköping for support with data collection and intervention. Thanks also to Cecilia Hedenstierna for data entry and Karl Wahlin for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, Strömberg A, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology [ESC]. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:933–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson B, Flegal K, et al. AHA heart disease and stroke statistics 2009. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC. Effect of marital quality on eight-year survival of patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1069–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Tijssen JG, van Veldhuisen DJ, Sanderman R. The objective burden in partners of heart failure patients; development and initial validation of the Dutch Objective Burden Inventory. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamura G, Mnich E, Nolan M, Wojszel B, Krevers B, Mestheneos L, Döhner H EUROFAMCARE Group. Family carers’ experiences using support services in Europe: empirical evidence from the EUROFAMCARE study. Gerontologist. 2008;48:752–71. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallager R, Luttik ML, Jaarsma T. Social support and self-care in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26:439–45. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31820984e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ågren S, Evangelista L, Strömberg A. Do partners of patients with heart failure experience caregiver burden? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9:254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach SR, Schulz R, Williamson GM, Miller LS, Weiner MF, Lance CE. Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:255–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molloy GJ, Johnston DW, Witham MD. Family caregiving and congestive heart failure. Review and analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd KJ, Murray SA, Kendall M, Worth A, Frederick BT, Clausen H. Living with advanced heart failure: a prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:585–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mårtensson J, Dracup K, Fridlund B. Decisive situations influencing spouses’ support of patients with heart failure. A critical incident technique analysis. Heart Lung. 2001;30:341–50. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.116245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies. Evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:323. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daugherty J, Saarmann L, Riegel B, Sornborger K, Moser D. Can we talk? Developing a social support nursing intervention for couples. Clin Nurse Spec. 2002;16:211–8. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strömberg A, Dahlström U, Fridlund B. Computer-based education for patients with chronic heart failure. A randomised, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on knowledge, compliance and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Fridlund B, Levin LA, Karlsson JE, Dahlström U. Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1014–23. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuifbergen A, Becker H, Rogers S, Timmerman G, Kullberg V. Promoting wellness for women with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999;31:73–9. doi: 10.1097/01376517-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parson MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gayle BM, Preiss RW. An overview of dyadic processes in interpersonal communication. In: Allen M, Preiss RW, Gayle BM, Burrell NA, editors. Interpersonal communication research: Advances through meta-analysis. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook WL, Kenny DA. Examination the validity of self-report assessments of family functioning: a question of the level of analysis. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:209–21. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carr DD. Building collaborative partnerships in critical care: the RN case manager/social work dyad in critical care. Prof Case Manag. 2009;14:121–32. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181a774c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: New Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. Conceptualization and measurement of health-related quality of life: comments on an evolving field. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan M, Karlsson J. Svensk manual och tolknings-guide [Swedish manual and interpretation guide] Gothenburg: Health Care Research Unit, Medical Faculty, Gothenburg University and Sahlgrenska Hospital; 1994. Hälsoenkät. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II (Svensk version) Sandviken: Psykologiförlaget; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moser DK, Dracup K. Psychosocial recovery from a cardiac event: the influence of perceived control. Heart Lung. 1995;24:273–80. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzén Årestedt K, Ågren S, Flemme I, Moser D, Strömberg A. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Control Attitude Scale for patients with heart disease and their family members. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(Suppl 1):125. doi: 10.1177/1474515114529685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaarsma T, Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Dracup K. Development and testing of the European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:363–70. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elmståhl S, Malmberg B, Annerstedt L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:177–82. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrén S, Elmståhl S. Family caregivers’ subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherence. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:157–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moser DK, Dracup K. Role of spousal anxiety and depression in patients’ psychosocial recovery after a cardiac event. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:527–32. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000130493.80576.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung ML, Pressler SJ, Dunbar SB, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Predictors of depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25:411–9. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181d2a58d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moser DK, Dracup K. Psychosocial recovery from a cardiac event: the influence of perceived control. Heart Lung. 1995;24:273–80. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(05)80070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moser DK, Riegel B, McKinley S, Doering LV, An K, Sheahan S. Impact of anxiety and perceived control on in-hospital complications after acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:10–6. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000245868.43447.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Rayens MK. The effects of depressive symptoms and anxiety on HRQOL in patients with heart failure and their spouses: testing dyadic dynamics using Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Cleary AA, Berman JS, Ewy GA. Health consequences of partner distress in couples coping with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2009;38:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekelman DB, Hutt E, Masoudi FA, Kutner JS, Rumsfeld JS. Defining the role of palliative care in older adults with heart failure. International Journal of Cardiology. 2008;125:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Deaton C, Smith AL, De AK, O’Brien MC. Family education and support interventions in heart failure: a pilot study. Nurs Res. 2005;54:158–66. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roccaforte R, Demers C, Baldassarre F, Koon T, Yusuf S. Effectiveness of comprehensive disease management programmes in improving clinical outcomes in heart failure patients. A meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:1133–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrén S, Elmståhl S. The relationship between caregiver burden, caregivers’ perceived health and their sense of coherence in caring for elders with dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:790–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow SK, Wong FK, Poon CY. Coping and caring: support for family caregivers of stroke survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:133–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]