Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are potent antigen-presenting cells known to regulate immune responses to self-antigens, particularly DNA. The mitochondrial fraction of necrotic cells was found to most potently promote human pDC activation, as reflected by Type I interferon release, which was dependent upon the presence of mitochondrial DNA and involved TLR9 and receptors for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE). Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a highly abundant mitochondrial protein that is functionally and structurally homologous to high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), was observed to synergize with CpGA DNA to promote human pDC activation. pDC Type I interferon responses to TFAM and CpGA DNA indicated their engagement with RAGE and TLR9, respectively, and were dependent upon endosomal processing and PI3K, ERK and NF-κB signaling. Together, these results indicate that pDC contribute to sterile immune responses by recognizing the mitochondrial component of necrotic cells and further incriminate TFAM and mitochondrial DNA as likely mediators of pDC activation under these circumstances.

Keywords: Cell necrosis, DAMP, IFNα, IRF-7, Sterile Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Antigens released from damaged cells and tissues promote potent immune responses, which contribute to many acute and chronic inflammatory diseases in humans. In contrast to programmed cell death (apoptosis) wherein immunogenic self-antigens are enzymatically degraded, cell necrosis is associated with the release of intact proteins and DNA. The latter can serve as endogenous “danger associated molecular patterns” (DAMPs) to alert the immune system to impending pathogen invasion (1). Being that mitochondria are derived from bacterial endosymbiots, they retain many bacterial features, including circular CpG-enriched DNA encoding for N-formylated peptides, and a dual-membrane structure with specialized lipids (e.g., cardiolipin). Each of these mitochondrial components possesses pro-inflammatory actions (2–4), which explains why the mitochondrial fraction of necrotic cells is particularly immunogenic (2, 5, 6).

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are highly efficient antigen-presenting cells that are specialized to produce large amounts of Type I interferons. Unlike monocytes and mature DCs, pDCs do not express TLR2, TLR3, TLR4 or TLR5, explaining their inability to respond to bacterial products such as endotoxins, peptidoglycans and flagellin or viral double-stranded RNA. However, pDCs do express TLR7 and TLR9, which are sensitive to ribonucleotides and DNA, respectively (7). Exogenous (e.g., bacterial) or endogenous (e.g., mitochondrial) non-methylated CpG dinucleotides are potent TLR9 ligands (8), which explains why mitochondrial DNA is strongly immunogenic relative to nuclear DNA (4).

Given that pDCs respond to DAMPs released from necrotic cells (9), they are poised to contribute significantly to the sterile immune response attendant to acute cell and tissue damage. A recent study by Zhang and colleagues suggests that mitochondrial (CpG-enriched) DNA contributes to systemic inflammation during critical illness (6). The nuclear transcription factor, high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), a putative DAMP (10), is shown to amplify pDC responses to CpG DNA by engaging receptors for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) (9); however, HMGB1 is confined to nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments during acute cell damage (10) and, as such, would not gain access to mitochondrial CpG DNA. In contrast, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), a structural and functional homologue of HMGB1 that is present in high abundance in mitochondria (11), is normally bound tightly to mitochondrial DNA (12), is released from acutely damaged cells (5) and possesses immunogenic properties comparable to HMGB1 (5). We therefore hypothesized that mitochondrial DAMPs, particularly mitochondrial (CpG-enriched) DNA and TFAM, would be potent endogenous activators of pDC. Based upon previous studies relating to HMGB1 (9), we further postulated that TFAM would specifically engage receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) to amplify CpG DNA (TLR9)-mediated pDC activation. These investigations have important implications for the pathogenesis of sterile inflammatory responses in the context of clinical conditions associated with necrotic cell death and tissue damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Human CpG-containing oligonucleotide, type A (CpGA, TLR9 ligand), mouse CpGA (mCpGA), FITC-labeled human CpGA (CpGA-FITC), guanosine-rich inhibitory oligonucleotide (G-ODN, TLR9 signaling inhibitor), an inhibitor of endosomal acidification (chloroquine), HEK-Blue™ hTLR2 cells and Quanti-Blue™ were obtained from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Cyclosporin H (CsH), Boc-Phe-Leu-Phe-Leu-Phe (Boc-FLFLF, BOC) and WRW4 (Trp-Arg-Trp-Trp-Trp-Trp) were acquired from Axxora, LLC (San Diego, CA), ChemPep, Inc. (Miami, FL) and Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) respectively. BAY 11-7085 and Heparin sodium were obtained from Calbiochem® (EMD Biosciences, Inc.; Rockland, MA) and APP Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Schaumburg, IL) correspondingly. Primary antibodies were acquired commercially: transcriptional regulator, interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7) and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; Santa Cruz, CA) and an endosomal marker, early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), p-Akt, p-ERK and p-NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; Danvers, MA). Immunofluorescent antibodies, DAPI, Alexa Fluor® 488 and Alexa Fluor® 555 were obtained from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Invitrogen Corp.; Carlsbad, CA). Anti-human TFAM polyclonal antibody was made by Spring Valley Laboratories, Inc. (Woodbine, MD). The epitope used to create the antibody was KQRKYG, which was chosen because the corresponding peptide sequence was unique relative to that of HMGB1. The HMGB1 blocking antibody was generously provided by Kevin J. Tracey, M.D. (Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY). Secondary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, LY294002 and Wortmannin were acquired from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. and Invitrogen Corp., respectively. IL-3 was obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). HepG2 and HEK-293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and cultured using DMEM/F-12 and MEM media (Invitrogen Corp.), respectively. Unless otherwise stated, all additional chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) using the best available grade.

Plasmid Construction and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

Recombinant mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) was synthesized as described in detail previously (5). In brief, the coding region of human TFAM was amplified by PCR, cloned into pcDNA3.1(−)/myc-His A (Invitrogen Corp.) and pDsRed-Express-C1 (Clontech Laboratories; Mountain View, CA) vectors in-frame or with added C-terminal myc epitope and 6×histidine tags and then transformed into E. coli-competent cells (DH5α, Invitrogen Corp.). The resultant TFAM plasmids, pcDNA3.1-TFAM.myc.6×His and pDsRed-TFAM-C1, were transfected into HEK-293 cells, and the resultant polyhistidine-tagged recombinant proteins (TFAM and DsRed-TFAM) were then purified by Ni-NTA nickel-chelating resin. Likewise, the coding region for human receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (hRAGE) comprising only the extracellular domain was cloned into the pcDNA3.1(−)/myc-His A vector and processed similarly to obtain recombinant soluble RAGE (sRAGE). The coding region of human RAGE [GenBank Accession No. BC020669 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/177)] was amplified by PCR using the pDNR-LIB-RAGE template (ATCC). The sense primer for human sRAGE (5′-CGAATTCCCACCATGGCTCAAAACATCACAGCCC-3′) introduced an EcoRI restriction site to facilitate cloning. The anti-sense primer for human sRAGE (5′-TGGTACCAGTTCCCAGCCCTGATCC-3′) introduced a KpnI restriction site (13, 14). The identity and function of the recombinant proteins were confirmed by Western blot, capillary-liquid chromatography-nanospray tandem mass spectrometry (Nano-LC/MS/MS) and the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (5). HMGB1 was synthesized and confirmed in a similar manner as detailed previously (5) for use in determining antibody cross-reactivity.

HepG2 Subcellular Fractionation

HepG2 cell necrosis was induced by freeze/thaw and was confirmed by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay, as described previously (5, 15). Cell lysates, along with nuclear, cytoplasmic and total mitochondrial protein cellular subfractions, were prepared from HepG2 cells using a differential centrifugation approach (16) with minor modifications. Genomic and mitochondrial DNA were removed, when indicated, using benzonase (Novagen; San Diego, CA). Great care was taken to ensure purity of the cellular subfraction proteins which was further confirmed by Western blot using antibodies against markers specific for plasma membrane (CEACAM-1), endoplasmic reticulum (calnexin), and mitochondria (COXII, HSP60) (5). The endotoxin level in each cellular subfraction protein was determined using the chromogenic Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (LAL, Associates of Cape Cod; East Falmouth, MA). When needed, samples were passed through AffinityPak™ Detoxi-Gel™columns (Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and re-tested by LAL to confirm that endotoxin levels were <5 pg/μg protein. The absence of Mycoplasma contamination was confirmed by PCR (see methodology below and Table 1 for primers employed) and by treating HEK-Blue™ hTLR2 cells [HEK-293 cells stably co-expressing a human TLR2 gene and a NF-κB-inducible SEAP (secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase) reporter gene that can be easily monitored using SEAP detection media (Quanti-Blue™) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.] with the isolated protein cellular subfractions, the recombinant proteins and the media bathing the cells (i.e., supernatants) from which the proteins were isolated or synthesized respectively (Figure S1)2.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for PCR.

| Gene | Amplicon (bp) | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Synthase 6 | 72 | Sense 5′-CCAATAGCCCTGGCCGTAC-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CGCTTCCAATTAGGTGCATGA-3′ | ||

| β-actin | 268 | Sense 5′-GCCAACCGCGAGAAGATGA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TGGTGGTGAAGCTGTAGCC-3′ | ||

| COX I | 66 | Sense 5′-TCCGCTACCATAATCATCGCT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CCGTGGAGTGTGGCGAGT-3′ | ||

| COX II | 63 | Sense 5′-TGCCCGCCATCATCCTA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCGTCTGTTATGTAAAGGATGCGT-3′ | ||

| COX III | 67 | Sense 5′-CCAATGATGGCGCGATG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CTTTTTGGACAGGTGGTGTGTG-3′ | ||

| COX IV | 151 | Sense 5′-CCTCCTGGAGCAGCCTCTC-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCAGCAAAGCTCTCCTTGAACTT-3′ | ||

| Cytochrome b | 60 | Sense 5′-CCCCACCCCATCCAACAT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCAGGCAGGCGCCAAG-3′ | ||

| IFNα1/13 | 171 | Sense 5′-TGGCTGTGAAGAAATACTTCCG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TGTTTTCATGTTGGACCAGATG-3′ | ||

| IFNα2 | 228 | Sense 5′-CCTGATGAAGGAGGACTCCATT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-AAAAAGGTGAGCTGGCATACG-3′ | ||

| IFNα4 | 343 | Sense 5′-GAAGAGACTCCCCTGATGAATGA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GCACAGGTATACACCAAGCTTCTTC-3′ | ||

| IFNα5 | 215 | Sense 5′-TCCTCTGATGAATGTGGACTCT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GTACTAGTCAATGAGAATCATTTCG-3′ | ||

| IFNα6 | 335 | Sense 5′-CTGTCCTCCATGAGGTGATT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TTCCTTCCTCCTTAACCTTT-3′ | ||

| IFNα7 | 271 | Sense 5′-CAGACATGAATTCAGATTCCCA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TTTCCTCACAGCCAGGATGA-3′ | ||

| IFNα8 | 174 | Sense 5′-GTGATAGAGTCTCCCCTGATGTAC-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CTTCAATCTTTTTTGCAAGTTGA-3′ | ||

| IFNα10 | 196 | Sense 5′-TGGCCCTGTCCTTTTCTTTACTT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCAAACTCCTCCTGGGGGAT-3′ | ||

| IFNα14 | 126 | Sense 5′-TGAATTTCCCCAGGAGGAA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCCCAAGCAGCAGATGAGTT-3′ | ||

| IFNα16 | 157 | Sense 5′-CAAAGAATCACTCTTTATCTGATGG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CAATGAGGATCATTTCCATGTTGAAT-3′ | ||

| IFNα17 | 209 | Sense 5′-TGTGATACAGGAGGTTGGGA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GTTTTCAATCCTTCCTCCTTAATA-3′ | ||

| IFNα21 | 388 | Sense 5′-ATCTCAAGTAGCCTAGCAATATTG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-AGGTCATTCAGCTGCTGGTT-3′ | ||

| IRF-7 | 69 | Sense 5′-GGGTGTGTCTTCCCTGGATA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TCGATGTCGTCATAGAGGCT-3′ | ||

| mRAGE 47–288 | 242 | Sense 5′-TATGGGGAGCTGTAGCTGGT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-GAAAGTCCCCTCATCGACAA-3′ | ||

| mRAGE 260–362 | 122 | Sense 5′-CCACTGGAATTGTCGATGAG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-ATCCACAATTTCTGGCTTCC-3′ | ||

| mRAGE 592–718 | 146 | Sense 5′-GGAGGAACCCATCCTACCTT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-ATTCCACCTTCAGGCTCAAC-3′ | ||

| mRAGE 760–1162 | 403 | Sense 5′-GACCTTGACCTGTGCCATCT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-ATTCAGCTCTGCACGTTCCT-3′ | ||

| Myco-280 | 280 | Sense 5′-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC-3′ | ||

| Myco-500 | 500 | Sense 5′-GGCGAATGGGTGAGTAACACG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCACA-3′ | ||

| Myco-717 | 717 | Sense 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTA-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTT-3′ | ||

| NADH 1 | 64 | Sense 5′-CCCTAAAACCCGCCACATCT-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CGATGGTGAGAGCTAAGGTC-3′ | ||

| NADH 4 | 65 | Sense 5′-ACCTTGGCTATCATCACCCG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-TAGGAAGTATGTGCCTGCGTTC-3′ | ||

| NADH 6 | 52 | Sense 5′-TGGTTGTCTTTGGATATACTACAGCG-3′ |

| Antisense 5′-CCAAGACCTCAACCCCTGAC-3′ |

Isolation, Culture and Stimulation of Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells (pDC)

Normal peripheral blood plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) were isolated from healthy human blood donors (n = 20) according to approved university IRB guidelines (including signed written informed consent) using the MACS CD304 (BDCA-4/Neuropilin-1) MicroBead positive selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pDCs were cultured in 96-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 105/ml in X-VIVO™ 15 (Lonza Walkersville; Walkersville, MD) with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. A one-time dose of IL-3 (25 ng/ml) was added soon after plating the cells to ensure pDC survival throughout the experimental timecourse. Polymyxin B (10 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) was also routinely added to the cells in each well to further block the effect of any possible endotoxin contamination. After 1 hour, desired concentrations of subcellular or mitochondrial fraction proteins, CpGA DNA and TFAM (alone or in combination) or immunoprecipitated TFAM (IP TFAM, see below) were then added to the medium. All pre-incubations with inhibitors of RAGE (sRAGE, 20 μg/ml; Heparin sodium, 10–100 U/ml), TLR9 (G-ODN, 10 μM), formyl peptide receptor (FPR) (CsH, 1 μM; BOC, 10 μM; WRW4, 20 μg/ml), endosomal acidification (chloroquine, 100 μM), PI3K signaling (LY294002, 5 μM; Wortmannin, 1 μM) or NF-κB signaling [BAY 11-7085 (BAY), 5 μM] were made as a one-time dose 30 minutes prior to protein fraction, CpGA DNA or TFAM addition. The cell supernatants were then collected at ~24 hours post-treatment and stored at −80°C for later analyses.

Interferon alpha (IFNα) Measurements

Human pDC or mouse splenocyte (see below) supernatants, collected ~24 hours post-treatment, were analyzed for their IFNα (R&D Systems, Inc.) concentrations by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Immunoprecipitation, PCR and Western Blotting

Necrotic HepG2 cell (~7 × 106/ml) lysates induced by freeze/thaw (5, 15) underwent immunoprecipitation (IP) designed to pull down native TFAM protein (IP TFAM). After the addition of protease inhibitors [1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.)] and centrifuging at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris, lysate supernatant was cleared of native immunoglobulins by the addition of ~30 μl/ml Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) with rotary agitation for 1 hour at 4°C. Following centrifugation (2000 rpm for 5 min), the supernatant was incubated with rabbit anti-human TFAM antibody (1 μg/100 μg IP protein) under rotary agitation overnight at 4°C. This antibody was confirmed as not having any cross-reactivity with HMGB1 (Figure S2). The next day, the supernatant was incubated with ~30 μl/ml Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose under rotary agitation for 4 hours at 4°C. The agarose beads were then pelleted as before, washed with PBS several times and re-suspended in 100 μl of PBS with added protease inhibitor. After heating at 100°C for 5 min, agarose beads were pelleted as before, and the resultant supernatant stored at −80°C.

To assess the presence and source of DNA, if any, associated with the IP protein, PCR was performed in 50 μl containing 1 × PCR buffer (without Mg2+), 1 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 200 nM of each PCR primer pair, 2 μl IP sample as the DNA template, and 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Corp.). The PCR conditions were 95°C for 3 min, followed by 32 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min and 72°C for 5 min. 10 μl of PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with 0.05% ethidium bromide. The primers used in PCR are identified in Table 1 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.; Coralville, IA). HepG2 mitochondrial DNA, isolated from the mitochondrial fraction of the cell using the Mitochondrial DNA Isolation Kit (BioVision, Inc.; Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, served as the positive control.

The presence of TFAM in the immunoprecipitated protein (IP TFAM) was confirmed by Western blot analysis using standard techniques with rabbit anti-human TFAM primary antibody (1:500). Pure human recombinant TFAM protein (0.5 μg) was used as a positive control.

Gene expression for select human genes (IRF-7 and all IFNα subtypes) was further determined in human pDCs using real-time PCR. One μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA by MultiScribe™ reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corp.; Carlsbad, CA) with random hexamers in a 50 μl reaction volume. PCR was performed in 20 μl of a mixture containing 1 μl of a cDNA sample, 5 pmol of each primer needed (Table 1) (17), and 10 μl of SYBR® GreenER™ PCR master mix (Invitrogen Corp.). Primer pairs were validated by real-time PCR and high-resolution gel electrophoresis to have a single band of desired size that was free of primer dimers. Amplification and detection were achieved with the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the profile of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Relative copy numbers and expression ratios for IRF-7 and all IFNα subtypes were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy

Normal human pDCs were isolated from peripheral blood by positive selection as detailed above and re-suspended (at 1 × 106 cells/ml) in X-VIVO™ 15 media with 1% FBS and 25 ng/ml IL-3 at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. After 1 hour, cells were treated depending upon the experiment being performed. To examine nuclear translocation of IRF-7, cells were incubated with TFAM (5 μg/ml) or CpGA DNA (1 μM) alone or in combination for 3 hours. Alternatively, to examine endosomal co-localization, cells were incubated with DsRed-TFAM (5 μg/ml) or CpGA-FITC DNA (1 μM) alone or in combination for 1.5 hours. At the end of timed treatment, cells were washed twice with PBS and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Cell suspensions were then applied to slides for further staining using cytospin. Following blockade with 5% goat serum/1% FBS in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, immunofluorescent staining of fixed pDC was carried out according to experimental design.

For IRF-7 nuclear translocation, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-human IRF-7 antibody (1:100) overnight at 4°C and then followed by goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cell nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (50 ng/ml, BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) for 10 minutes. Positive translocation of IRF-7 was observed to change pDC nuclei from red to yellow in color. This was quantified by determining the number of positive cells as a percentage of the total cell count in a minimum of 10 high power fields (40X) for each of 3 experimental preparations for each treatment group. For endosomal co-localization, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-human EEA1 antibody (1:100) overnight at 4°C and then followed by either goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled (when staining in conjunction with DsRed-TFAM treatment) or Alexa Fluor® 555-labeled (when staining in conjunction with CpGA-FITC DNA treatment) secondary antibodies (1:500) for 1 hour at room temperature. In this case, cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (100 ng/ml) for 10 minutes. Immunofluorescence was then evaluated using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Mouse pDC Expansion and Splenocyte Preparation

All experiments were approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Eight-week old, adult, male, C57BL/6 mice (~25 g) (The Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, ME) were employed for in vivo pDC expansion and as a source for splenocytes. pDC expansion was carried out using melanoma cells [expressing murine (Flt3)] as previously described (18, 19). Briefly, 4 × 106 B16 melanoma cells (C57BL/6 background), transfected with mouse recombinant Flt3-ligand (Flt3L) cDNA using an MFG-retroviral vector, were suspended in sterile saline and injected subcutaneously in two sites over both flanks. Mice were euthanized when the tumor size reached 1–1.5 cm in diameter (after 3–4 weeks) (18), and the spleens were harvested.

Single cell splenocyte suspensions were prepared following mechanical disaggregation of the spleen tissue and gently passing the released cells and tissue fragments through a 70 μm nylon cell strainer. Following erythrocyte lysis, cells were washed and then suspended in RPMI 1640 (supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% FBS) (Invitrogen Corp.). Cells were then cultured in 48-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml in the above media with only 2% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. Polymyxin B (10 μg/ml) was routinely added to the cells in each well to further block the effect of any possible endotoxin contamination. After 1 hour, desired concentrations of CpGA DNA and TFAM (alone or in combination) were then added to the medium. All pre-incubations with inhibitors of RAGE (sRAGE, 20 μg/ml; Heparin sodium, 1–100 U/ml), TLR9 (G-ODN, 10 μM), endosomal acidification (chloroquine, 100 μM), PI3K signaling (LY294002, 5 μM; Wortmannin, 1 μM), NF-κB signaling (BAY, 5 μM) or HMGB1 blocking antibody (5 μg/ml) were made as a one-time dose 30 minutes prior to TFAM and/or CpGA DNA addition. The cell supernatants were then collected at ~24 hours post-treatment and stored at −80°C for later analyses. Similar experiments involving treatment with CpGA DNA and TFAM (alone or in combination) were carried out in mouse splenocytes isolated from matched RAGE knockout (RAGE −/−) mice (generously provided by Angelika Bierhaus, Ph.D. and Peter P. Nawroth, M.D.)3 wherein RAGE depletion was confirmed by real-time PCR (see Table 1 for primers employed and Figure S3). Relative copy numbers and expression ratios for the various RAGE-associated gene loci were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene, β-actin.

Elevated pDC populations following Flt3L expansion were identified via flow cytometry following immunofluorescent staining of splenocytes with mouse anti-plasmacytoid dendritic cell antigen 1 (mPDCA-1)-FITC (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.).

Signaling in Mouse Splenocytes

PI3K/Akt, ERK and NF-κB signaling in mouse splenocytes was investigated following their treatment with CpGA DNA (0.3 μM) alone or in combination with TFAM (5 μg/ml). Cells were collected at 15, 30 and 60 minutes post-treatment and processed for Western blot analyses according to standard techniques. Possible inhibition of these signaling pathways was further examined by pre-treatment with sRAGE (20 μg/ml), LY294002 (5 μM) or BAY (5 μM) for 30 minutes. The rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies employed were p-Akt (1:500), p-ERK (1:1000) and p-NF-κB (1:1000). Protein band densities were normalized to protein load established by subsequent use of mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (1:5000) and compared to corresponding bands from untreated cells.

Statistical Analyses

The data was derived from independent experiments, as designated in the figure legends, and was expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was based upon a value of p ≤ 0.05. SigmaPlot 12.0 and SYSTAT 13.0 software were used to plot the data and carry out the statistical analyses, respectively. pDC IFNα release in response to various treatments were compared to untreated controls using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Additional comparisons involving pre-treatment inhibition studies and all experiments relating multiple groups were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Where appropriate, post hoc analyses between group rank means were performed using Dunn’s test.

RESULTS

Selective Activation of pDCs by Mitochondrial Antigens Involved TLR9 and RAGE

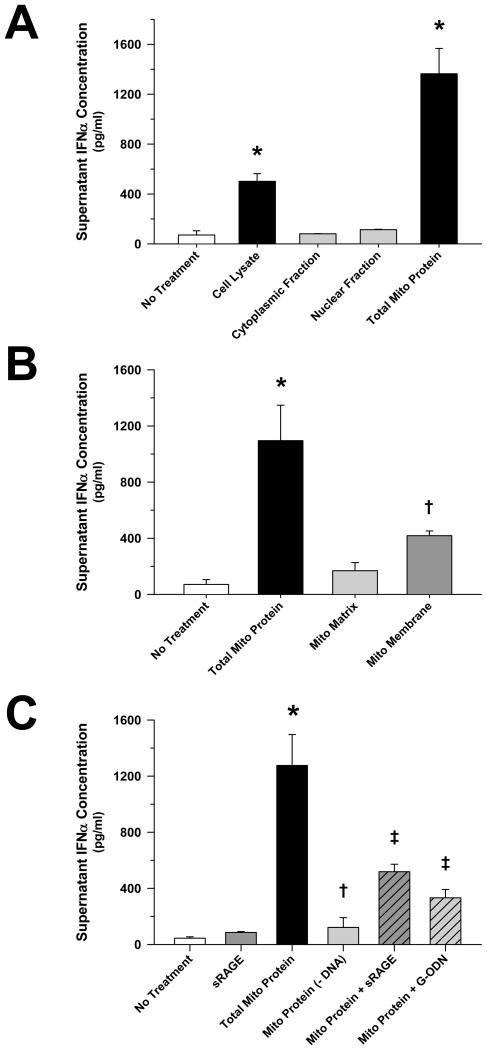

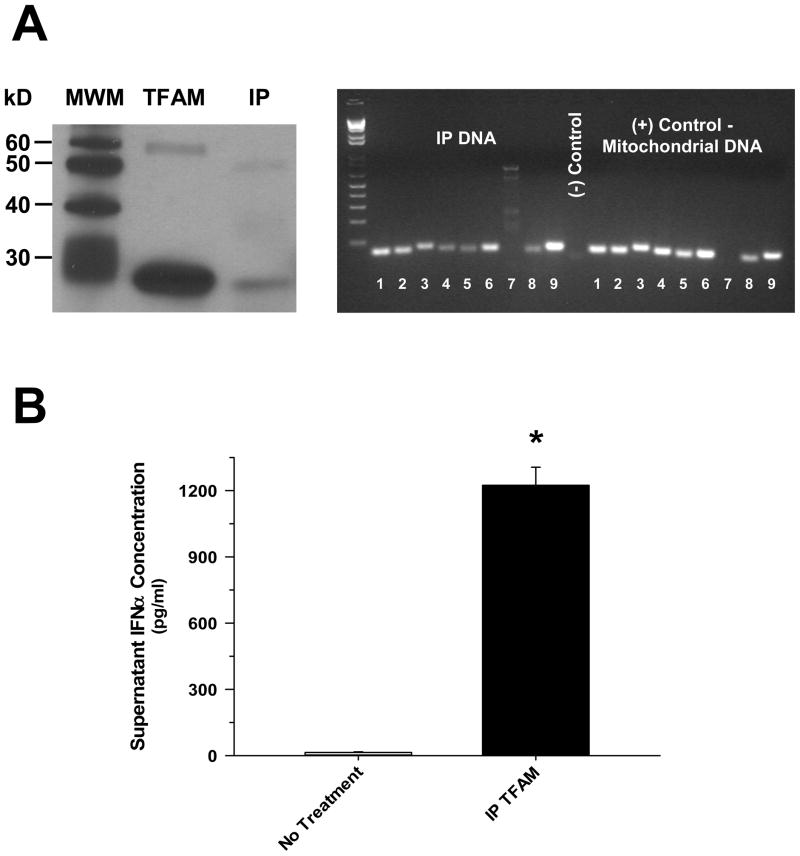

Previous studies have demonstrated that nuclear HMGB1 (1, 10, 15), and various mitochondrial antigens (2–6), are potent endogenous danger signals. In order to determine which component of necrotic cells was most immunogenic, pDCs were exposed to equal concentrations of purified cellular fractions derived from necrotic HepG2 cells. pDCs were observed to respond most vigorously in terms of Type I interferon (IFN) release to the mitochondrial component of the cell (Figure 1A), and this response was largely dependent upon the presence of mitochondrial DNA (Figure 1B). An essential role of TLR9 was confirmed by the significant attenuation of pDC activation by mitochondrial antigens in the presence of G-ODN, a competitive TLR9 inhibitor (Figure 1C). In keeping with previous studies implicating RAGE agonists as important danger signals in the setting of cell death (1, 10), pre-treatment with sRAGE notably inhibited mitochondrial antigen-mediated pDC activation (Figure 1C). TFAM, a high-abundance mitochondrial protein normally bound to mitochondrial DNA (12) that is released from necrotic cells (5), was shown to remain associated with mitochondrial DNA upon immunoprecipitation following necrotic cell death (Figure 2A), and treatment with this IP TFAM induced significant pDC IFNα release (Figure 2B). This observation led to the consideration that TFAM may modify pDC activation by DNA.

Figure 1. Selective Induction of pDC IFNα Release by the Mitochondrial Cellular Fraction Involves DNA/RAGE-dependent Mechanisms.

The presented data was derived from at least 5 independent experiments. (A) 24 hours after exposure to HepG2 cell lysate or subcellular fractions (5 μg/ml), purified pDC (1 × 105 cells/ml) IFNα release was limited to the mitochondrial compartment, (B) particularly the mitochondrial membrane fraction (*†p < 0.01, compared to no treatment). (C) Mitochondrial protein-induced pDC IFNα release was significantly reduced at 24 hours post-treatment by DNA removal, and RAGE (sRAGE, 20 μg/ml) or TLR9 (G-ODN, 10 μM) inhibition (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.01, compared to mitochondrial protein alone, and ‡p < 0.05, relative to no treatment and mitochondrial protein alone).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial DNA Is Uniquely Associated with TFAM when Released from Necrotic HepG2 Cells which Can Subsequently Induce pDC Type I IFN Activation.

The presented data was representative of 3 independent preparations. (A) Necrotic HepG2 cell lysates subjected to immunoprecipitation with a TFAM antibody, yielded IP TFAM protein (Western blot, left) that is bound to DNA (~120 ng/μl protein) that has the “unique” gene expression profile of mitochondrial DNA [post-PCR cDNA gel, right – 8 of 13 mitochondrial genes demonstrated along with 1 non-mitochondrial (COX IV) (1 – NADH 1, 2 – NADH 4, 3 –NADH 6, 4 – COX I, 5 – COX II, 6 – COX III, 7 – COX IV, 8 – Cytochrome b, and 9 – ATP synthase 6)]. (B) Exposure of purified human pDCs (1 × 105 cells/ml) to IP TFAM (0.5 μg/ml) yielded marked release of IFNα by 24 hours post-treatment (*p < 0.01, compared to no treatment).

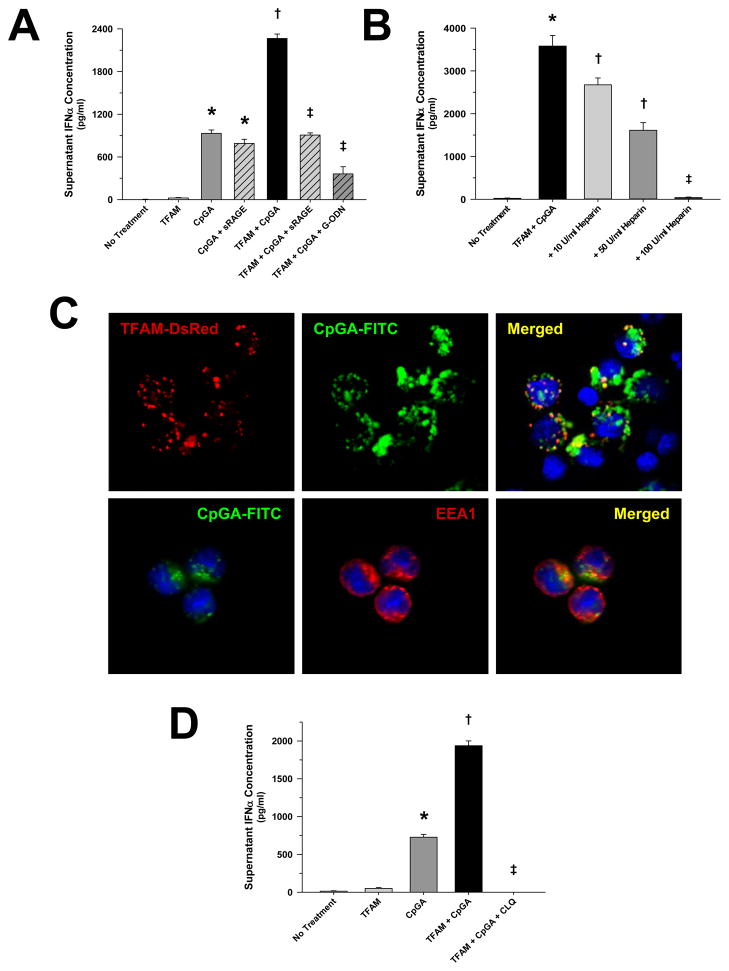

TFAM Augmented pDC Activation through RAGE and Endosomal Processing

HMGB1, a potent RAGE agonist, is known to promote pDC activation by facilitating the association of TLR9 receptors and agonists within endosomes (9). Given that TFAM is normally bound to mitochondrial DNA thereby preventing DNA degradation (12) and is homologous in structure and function to HMGB1 (11), we tested the hypothesis that TFAM augments pDC activation by CpGA DNA, a potent TLR9 agonist, through a RAGE-dependent mechanism. As presented in Figure 3A, treatment with highly purified human recombinant TFAM significantly enhanced IFNα release in the presence of CpGA DNA, and this synergistic effect was attenuated in the presence of sRAGE or the TLR9 inhibitor, G-ODN. Like sRAGE, RAGE-ligand inhibition was further demonstrated wherein pre-treatment with heparin decreased pDC IFNα release in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3B). Interestingly, there was no detectable effect upon TFAM + CpGA-induced pDC Type I IFN activation by FPR inhibition (Figure S4). In keeping with previous investigations showing that antigen-dependent TLR9 signaling in pDCs occurred within endosomes (20), fluorescence confocal microscopy confirmed early co-localization of TFAM and CpGA DNA within pDC endosomes (Figure 3C). Dramatic inhibition of pDC responses to TFAM + CpGA DNA by pre-treatment with an inhibitor of endosomal acidification (chloroquine) confirmed the essential role of endosomal signaling for pDC TLR9-dependent IFNα production (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. TFAM Amplifies CpGA DNA-induced pDC IFNα Release which Is Dependent upon RAGE and Endosomal Processing.

The presented data was derived from or is representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (A) CpGA DNA (0.5 μM)-induced pDC (1 × 105 cells/ml) IFNα release was significantly augmented by co-incubation with human recombinant TFAM (5 μg/ml) 24 hours post-treatment. This effect was dramatically attenuated through RAGE (sRAGE, 20 μg/ml) or TLR9 (G-ODN, 10 μM) inhibition (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.01, compared to CpGA DNA alone, and ‡p < 0.01, relative to no treatment and the TFAM + CpGA treatment group). (B) 24 hours post-treatment, heparin notably inhibited TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced pDC IFNα release in a dose-dependent manner (*p < 0.01, compared to no treatment; †p < 0.05, relative to no treatment and the TFAM + CpGA treatment group, and ‡p < 0.01, compared to the TFAM + CpGA treatment group). (C) Representative fluorescent photomicrographs demonstrating co-localization of recombinant human TFAM (TFAM-DsRed) and CpGA DNA (CpGA-FITC) and co-localization of CpGA DNA (CpGA-FITC) with endosomes (EEA1) within pDCs at 1.5 hours post-treatment (original magnification = 40X). (D) TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced IFNα release was completely prevented at 24 hours post-treatment by inhibiting endosomal acidification with chloroquine (CLQ, 100 μM) pre-treatment (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.01, compared to CpGA DNA alone, and ‡p < 0.01, relative to the TFAM + CpGA treatment group).

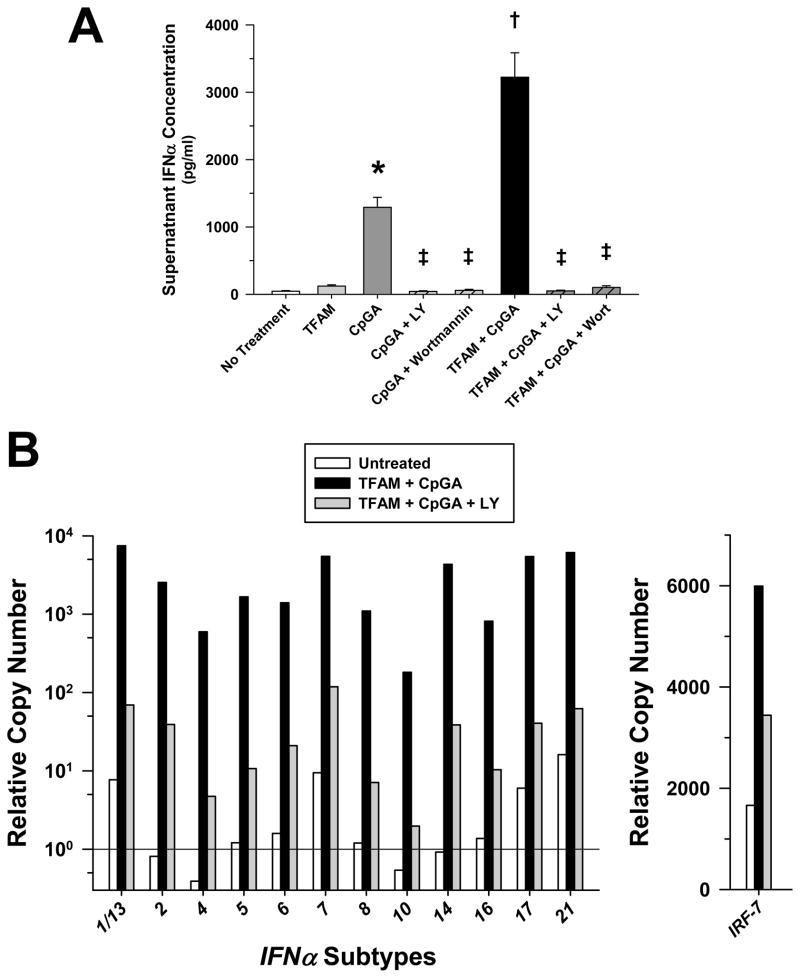

PI3K Was Essential for pDC Type I IFN Responses to TFAM and CpGA DNA

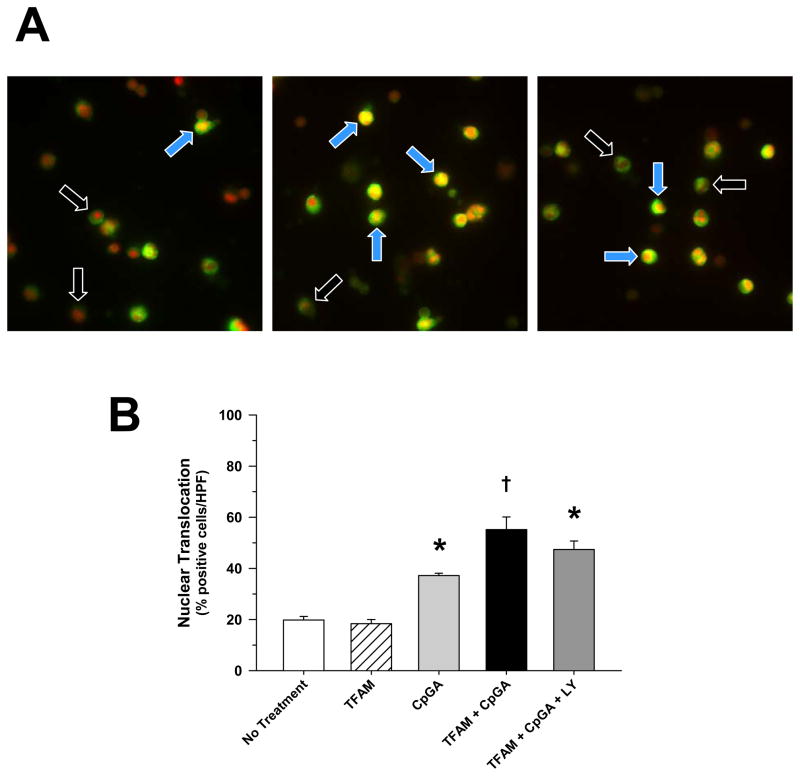

Guiducci and colleagues recently reported that PI3K regulates the transcription of IFNα by facilitating nuclear translocation of interferon regulatory factor-7 (IRF-7) (21). Figure 4A provides evidence that PI3K was essential for activation of pDCs by TFAM and CpGA DNA wherein PI3K inhibition (LY294002, Wortmannin) completely blocked antigen-induced IFNα release. Likewise, NF-κB inhibition (BAY) proved equally effective at preventing antigen-induced pDC Type I IFN activation (data not shown). As previously reported and in contrast to other TLR ligands (22), TLR9-dependent pDC activation by TFAM and CpGA DNA promoted the transcription of all IFNα subtypes. Moreover, the expression of all IFNα subtype transcripts depended upon PI3K signaling (Figure 4B). In contrast to the earlier study (16), PI3K signaling minimally influenced IRF-7 nuclear translocation, as reflected by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Increased pDC IFNα Transcript and Release Induced by CpGA DNA or TFAM + CpGA DNA Treatment Involves PI3K and IRF-7 Signaling.

The presented data was derived from or is representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (A) Both CpGA DNA and TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced pDC IFNα release was completely inhibited at 24 hours post-treatment following LY294002 (LY, 5 μM) or Wortmannin (1 μM) pre-treatment (*p < 0.01, compared to no treatment; †p < 0.01, relative to CpGA DNA alone, and ‡p < 0.01, compared to the CpGA or TFAM + CpGA treatment groups). (B) Representative relative gene expression in pDCs as determined by real-time PCR was increased for all subtypes of IFNα (nearly 3 orders of magnitude) and of IRF-7 following TFAM + CpGA DNA treatment at ~4 hours post-treatment. This increased expression was markedly reduced (nearly 2 orders of magnitude for all IFNα subtypes) with LY294002 (LY, 5 μM) pre-treatment.

Figure 5. TFAM + CpGA DNA-Induced Nuclear Translocation of IRF-7 in pDCs Occurs Independently of PI3K Signaling.

The presented data was derived from or is representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (A) Representative fluorescent photomicrographs of nuclear translocation of IRF-7 in pDCs in untreated (left), TFAM + CpGA DNA-treated (middle) and TFAM + CpGA DNA-treated following LY294002 (5 μM) pre-treatment (right) conditions 3 hours post-treatment [black arrows – negative cells, blue arrows – positive cells] (original magnification = 40X). Positive translocation of IRF-7 (green) was observed when pDC nuclei changed from red to yellow in color. (B) No significant change [positive cell count as a percent of the total per high power field (HPF)] was determined in the TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced increase in nuclear translocation of IRF-7 following LY294002 (LY, 5 μM) pre-treatment (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.05, compared to CpGA DNA alone).

Murine Splenocyte Responses Mirror Isolated Human pDC Responses to TFAM and CpGA DNA

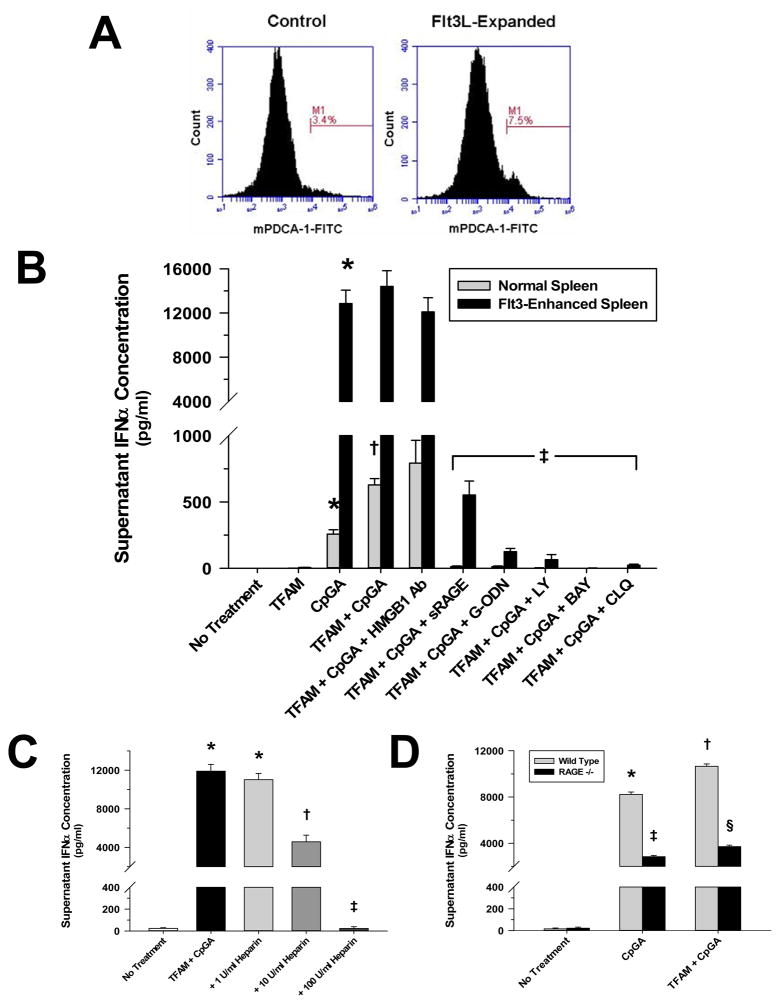

The relevance of the in vitro human pDC experiments was explored in a murine splenocyte culture modeling immune responses to antigens (e.g., circulating) in the spleen. The spleen is a specialized tissue enriched with dendritic cells that are responsive to circulating microbial and endogenous danger signals (23–25). As with isolated human pDCs, TFAM enhanced the induction of Type I IFN responses by the TLR9 agonist, and this effect was RAGE-dependent. Furthermore, inhibitors of endosomal acidification (chloroquine), PI3K-signaling (LY294002) and NF-κB signaling (BAY) attenuated Type I interferon production in response to TFAM and CpGA DNA (Figure 6B). Conversely, there was no significant effect upon antigen-induced IFNα release following pre-treatment with HMGB1 blocking antibody. As expected, enhanced (~2-fold) proliferation of pDCs in the spleen consequent to Flt3L expansion (Figure 6A) was associated with an increased response to the TLR9 agonist (Figure 6B). As in human pDCs, heparin pre-treatment further supported the significance of RAGE involvement by demonstrating dose-dependent inhibition of TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced IFNα release (Figure 6C). This was shown even more relevant by the significant reductions in Type I IFN activation in splenocytes from RAGE −/− mice (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. TFAM Amplifies CpGA DNA-induced IFNα Release in Mouse Splenocytes which Is Dependent upon the pDC Population Size, RAGE, TLR9, Endosomal Processing and PI3K Signaling.

The presented data was derived from or is representative of at least 5 independent experiments. (A) Flow cytometry results demonstrating the increase in the pDC-positive (as indicated using the specific pDC marker, mPDCA-1) cell population in mouse splenocytes following exposure to B16 melanoma cell-expressed murine Flt3L. Expansion was observed to routinely double pDC populations after the 3–4 week exposure (Note percent positive cell count increase at M1.). (B) mCpGA DNA (0.3 μM)-induced IFNα release was increased by human recombinant TFAM (5 μg/ml) co-incubation in mouse splenocytes (1 × 106 cells/ml) 24 hours post-treatment. This effect was significantly attenuated through RAGE (sRAGE, 20 μg/ml), TLR9 (G-ODN, 10 μM), endosomal acidification [chloroquine (CLQ), 100 μM], PI3K signaling (LY, 5 μM) or NF-κB signaling (BAY, 5 μM) inhibition (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.01, compared to CpGA DNA alone, and ‡p < 0.01, relative to the TFAM + CpGA treatment group). Pre-treatment with HMGB1 blocking antibody had no effect upon TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced splenocyte IFNα release. Notably elevated splenocyte IFNα release was demonstrated in splenocytes subjected to Flt3L-induced expansion consistent with increased pDC cell populations. (C) Inhibition of TFAM + CpGA DNA-induced splenocyte Type I IFN activation by heparin was dose-dependent (*p < 0.01, compared to no treatment; †p < 0.05, relative to no treatment and the TFAM + CpGA treatment group, and ‡p < 0.01, compared to the TFAM + CpGA treatment group). (D) Splenocytes from RAGE −/− mice demonstrated significantly diminished IFNα release in response to CpGA DNA treatment alone or in combination with TFAM (*p < 0.01, relative to no treatment; †p < 0.05, compared to no treatment and CpGA DNA alone; ‡p < 0.05, relative to CpGA DNA alone, and §p < 0.01, compared to the TFAM + CpGA treatment group).

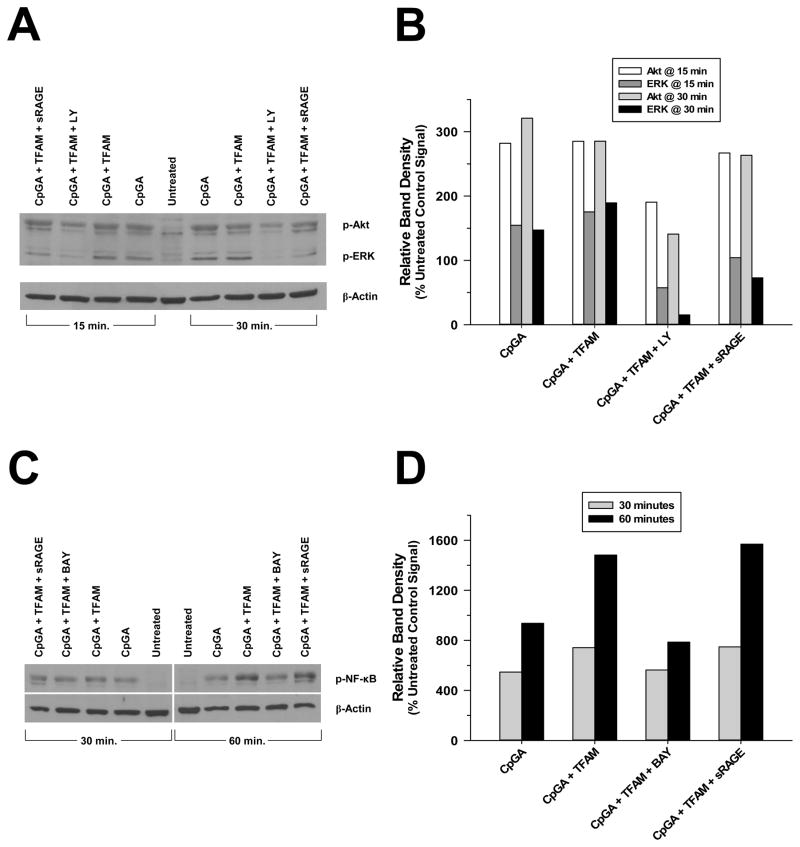

As expected, corresponding cell signaling experiments demonstrated that relative expressions of p-Akt, p-ERK and p-NF-κB were amplified within 15–30 minutes of CpGA DNA treatment alone or in combination with TFAM (Figure 7). Pre-treatment with inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002) and NF-κB (BAY 11-7085) greatly attenuated the associated p-Akt (Figures 7A and 7B) and p-NF-κB (Figures 7C and 7D) expressions, as anticipated. PI3K inhibition markedly decreased p-ERK expression as well (Figure 7B). Likewise, inhibition of RAGE (sRAGE) notably diminished the expression of p-ERK but had no detectable effect upon p-Akt or p-NF-κB expressions (Figures 7B and 7D).

Figure 7. Cell Signaling in Mouse Splenocytes in Response to CpGA DNA + TFAM Exposure Involves the Akt, ERK and NF-κB Pathways.

The presented data is representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (A) Representative photomicrograph of a Western blot demonstrating the changes observed in p-Akt and p-ERK signaling 15 and 30 minutes after CpGA DNA and TFAM (alone or in combination) treatment and the latter following LY294002 or sRAGE pre-treatment. (B) Relative expression of each protein was dramatically elevated in response to both treatments at each timepoint and markedly reduced by PI3K (LY) inhibition. RAGE inhibition (sRAGE) diminished p-ERK only. (C) Representative photomicrograph of a Western blot demonstrating the changes observed in p-NF-κB signaling 30 and 60 minutes after CpGA DNA and TFAM (alone or in combination) treatment and the latter following BAY 11-7085 or sRAGE pre-treatment. (D) Relative expression was notably increased in response to both treatments at each timepoint and decreased by NF-κB (BAY) inhibition. RAGE inhibition (sRAGE) had no discernable effect. In both cases, β-actin served as a loading control for normalization.

DISCUSSION

The cause of sterile inflammation in the context of cell necrosis (tissue damage) is a topic of great interest and ongoing controversy (1). Mitochondria are of particular interest given their bacterial origins and retention of bacterial features, including CpG-enriched DNA encoding for N-formylated peptides (2–6). Previous studies have documented the proinflammatory actions of mitochondrial DAMPs released into various body compartments, including blood (6), synovial fluid (2) and liver tissue (26); however, uncertainties exist relating to how mitochondrial antigens engage immune cells to promote inflammation.

pDCs play an essential role as sentinels of the immune system, providing immune surveillance for potentially hazardous exposures (7) and regulating the balance between innate and adaptive immune responses (27). pDCs are present in most tissues where they serve as excellent antigen-presenters and are the primary producers of Type I interferons in response to activation of specialized receptors that are sensitive to microbial RNA (TLR7) and CpG motif-enriched DNA (TLR9) (7). pDCs also respond to endogenous danger signals (9). In the context of cell necrosis, the current study indicates that the mitochondrial fraction is by far the most potent in terms of activating pDCs and further incriminates TFAM and mitochondrial (non-methylated CpG-enriched) DNA as mediators of this response.

HMGB1 is a nuclear protein that is believed to cause inflammation when released into the extracellular space, particularly following cell necrosis (15, 28). However, HMGB1 is a “sticky” protein that binds avidly to DNA and to bacterial lipids, including endotoxins (5, 29), and contamination with the latter likely contributes to the potent activation of inflammatory cells by recombinant HMGB1 produced in E. coli (28, 30). Although highly purified HMGB1 is capable of binding mitochondrial DNA (5), it normally associates with nuclear DNA to promote transcription and repair or mobilizes to the cytoplasm during cell stress (10). TFAM is a functional and morphological homologue of HMGB1 (11), sharing a highly conserved DNA-binding sequence that is common among HMG-family proteins (31, 32). TFAM is normally confined to the mitochondrial compartment where it is shown to strongly associate with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (12). TFAM is essential for mtDNA transcription and attenuates mtDNA breakdown (12). This study is the first to show that TFAM remains bound to mtDNA following cell necrosis and could thereby promote the activation of readily available antigen-presenting cells, particularly TLR9-expressing pDCs.

In keeping with the previous study by Tian et al relating to HMGB1 (9), we found that exposure to TFAM alone was insufficient to elicit pDC activation; whereas, TLR9-mediated immune responses to CpGA DNA were significantly amplified by TFAM through a RAGE-dependent mechanism. We further showed that RAGE, TLR9 and TFAM co-localize within endosomes, and that endosomal processing was essential for pDC activation under these conditions. Our findings are in keeping with previous studies showing that RAGE agonists likely promote antigen binding to TLR9 within endosomes, thereby enhancing pDC activation (9). Further support for RAGE-mediated activation of pDCs by CpGA DNA and TFAM is provided by the heparin experiments, wherein increasing titrations of heparin were shown to suppress pDC activation. Heparin is a potent competitive inhibitor of RAGE-ligand interactions and associated inflammatory responses (33, 34). In this regard, HMG family proteins and CpG DNA independently bind with high affinity to RAGE (35). We suspect that the association of TFAM with immunogenic mitochondrial DNA enhances the affinity of the latter for RAGE.

The signaling mechanisms by which pDC Type I IFN responses are regulated have been recently identified. A recent study by Guiducci et al indicates that PI3K-dependent nuclear translocation of transcription factor IRF-7 is essential for pDC Type I IFN responses (21). Our data from human pDCs confirmed that PI3K is essential for IFNα gene transcription and protein release in response to TLR9 activation; however, PI3K did not significantly influence nuclear IRF-7 translocation. Our findings implicate other mechanisms, including PI3K-dependent activation of ERK and NF-κB. PI3K may also influence IFNα transcription through the regulation of histone deacetylase enzymes (36, 37), which would explain the dramatic suppression of all IFNα subtype transcripts by PI3K inhibition despite the demonstrated nuclear presence of IRF-7.

These mechanisms were further investigated in cultured splenocyte preparations designed to model more complex immune environments encountered in vivo. The spleen is enriched with a mixed population of dendritic cells, including pDCs (24, 25), which are induced to proliferate in response to Flt3L. The murine, cultured splenocyte experiments largely mirrored the findings in purified human pDCs in that TFAM and CpGA DNA were shown to promote Type I IFN responses, which depended upon RAGE and TLR9 receptors and signaling pathways involving endosomes, PI3K, ERK and NF-κB. Thus, these pathways may be reasonable targets to limit the sterile inflammatory response in vivo.

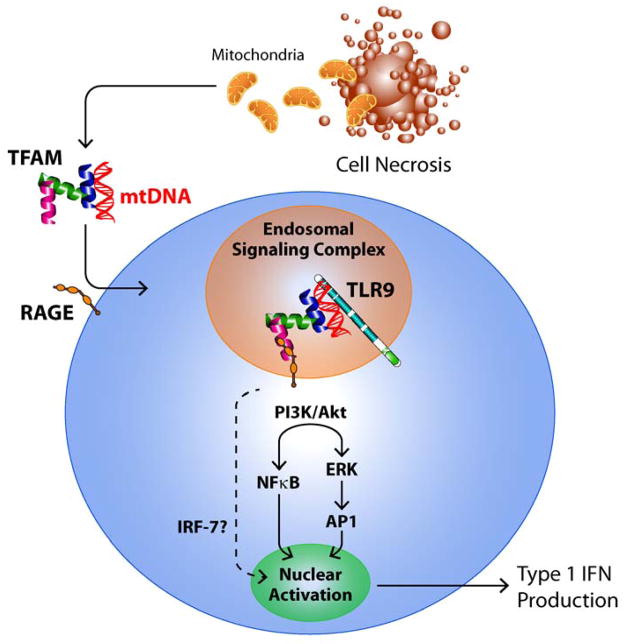

In summary, the mitochondrial fraction of the cell was demonstrated to be the most potent in terms of promoting pDC-mediated Type I IFN responses in the setting of cell necrosis, which was dependent upon TLR9 and RAGE activation. Mitochondrial DNA, which is enriched in CpG motifs, and TFAM, a homologue of HMGB1, were incriminated as critical mitochondrial activators of TLR9 and RAGE, respectively. As shown schematically in Figure 8, our data further indicated that endosomal processing and PI3K, ERK and NF-κB signaling were essential for induction of Type I IFN production by TFAM and CpGA DNA. Given that pDCs are potent regulators of innate and adaptive immune responses (27), and that mitochondrial DNA remains associated with TFAM after its release from damaged cells, this study identifies TFAM as a novel and potentially important endogenous danger signal.

Figure 8. Schematic Representation of pDC Activation by Necrotic Cells.

To summarize the findings presented herein, the data demonstrated that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) remained in association with TFAM upon release from necrotic cells. TFAM and mtDNA then associated with pDC RAGE and TLR9, respectively, to promote endosomal signal transduction via PI3K/Akt and ERK to induce IFNα gene transcription and protein formation. IRF-7 translocation to the nucleus was not PI3K-dependent and was insufficient for Type I IFN production. This schematic conforms to previous studies indicating that Type 1 IFN production is regulated by IRF-7, MAPKs (which activate AP-1) and NF-κB (38).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kevin J. Tracey, M.D. (Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY) for generously providing the HMGB1 blocking antibody employed in these experiments and Angelika Bierhaus, Ph.D. and Peter P. Nawroth, M.D. (Department of Medicine I and Clinical Chemistry, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany) for generously sharing their RAGE −/− mice used in this study.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by NIH R03-AI62740 (EDC), R21-AI083912 (EDC), and R01-HL086981-01 (DLK) and the OSU Medical Center Davis Developmental Grant (EDC).

The on-line version of this article contains supplemental material.

Provided through a Material Transfer Agreement with Angelika Bierhaus, Ph.D. and Peter P. Nawroth, M.D., Department of Medicine I and Clinical Chemistry, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany.

References

- 1.Rock KL, Kono H. The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:99–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carp H. Mitochondrial N-formylmethionyl proteins as chemoattractants for neutrophils. J Exp Med. 1982;155:264–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum H. Mitochondrial antigens, molecular mimicry and autoimmune disease. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1995;1271:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins LV, Hajizadeh S, Holme E, Jonsson IM, Tarkowski A. Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:995–1000. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crouser ED, Shao G, Julian MW, Macre JE, Shadel GS, Tridandapani S, Huang Q, Wewers MD. Monocyte activation by necrotic cells is promoted by mitochondrial proteins and formyl peptide receptors. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2000–2009. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a001ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, Brohi K, Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YL. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nature Immunol. 2004;12:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda K, Richez C, Uccellini MB, Richards RJ, Bonegio RG, Akira S, Monestier M, Corley RB, Vigliant GA, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rifkin IR. Requirement for DNA CpG content in TLR9-dependent dendritic cell activation induced by DNA-containing immune complexes. J Immunol. 2009;183:3109–3117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sims GP, Rowe DC, Rietdijk ST, Herbst R, Coyle AJ. HMGB1 and RAGE in inflammation and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parisi MA, Clayton DA. Similarity of human mitochondrial transcription factor 1 to high mobility group proteins. Science. 1991;252:965–969. doi: 10.1126/science.2035027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang D, Kim SH, Hamasaki N. Mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM): roles in maintenance of mtDNA and cellular functions. Mitochondrion. 2007;7:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumano-Kuramochi M, Xie Q, Sakakibara Y, Niimi S, Sekizawa K, Komba S, Machida S. Expression and characterization of recombinant C-terminal biotinylated extracellular domain of human receptor for advanced glycation end products (hsRAGE) in Escherichia coli. J Biochem. 2008;143:229–236. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlueter C, Hauke S, Flohr AM, Rogalla P, Bullerdiek J. Tissue-specific expression patterns of the RAGE receptor and its soluble forms – a result of regulated alternative splicing? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1630:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair JR, McGuire JJ. Submitochondrial localization of the mitochondrial isoforms of folylpolyglutamate synthetase in CCRF-CEM human T-lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Remoli ME, Giacomini E, Lutfalla G, Dondi E, Orefici G, Battistini A, Uzé G, Pellegrini S, Coccia EM. Selective expression of Type I IFN genes in human dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:366–374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mach N, Gillessen S, Wilson SB, Sheehan C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Differences in dendritic cells stimulated in vivo by tumors engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or Flt3-ligand. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3239–3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papenfuss TL, Kithcart AP, Powell ND, McClain MA, Glenapp IE, Shawler TM, Whitacre CC. Disease-modifying capability of murine Flt3-ligand DCs in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1510–1518. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilliet M, Cao W, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: sensing nucleic acids in viral infection and autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:594–606. doi: 10.1038/nri2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guiducci C, Ghirelli C, Marloie-Provost MA, Matray T, Coffman RL, Lui YJ, Barrat FJ, Soumelis V. PI3K is critical for the nuclear translocation of IRF-7 and type I IFN production by human plasmacytoid predendritic cells in response to TLR activation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:315–322. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coccia EM, Severa M, Giacomini E, Monneron D, Remoli ME, Julkunen I, Cella M, Lande R, Uzé G. Viral infection and Toll-like receptor agonists induce a differential expression of type I and λ interferons in human plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:796–805. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soloff AC, Barratt-Boyes SM. Enemy at the gates: dendritic cells and immunity to mucosal pathogens. Cell Res. 2010;20:872–885. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wluka A, Olszewksi WL. Innate and adaptive processes in the spleen. Ann Transplant. 2006;11:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villadangos JA, Heath WR. Life cycle, migration and antigen presenting functions of spleen and lymph node dendritic cells: limitations of the Langerhans cells paradigm. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald B, Pittman K, Menezes GB, Hirota SA, Slaba I, Waterhouse CC, Beck PL, Muruve DA, Kubes P. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulendran B. Modulating TH1/TH2 responses with microbes, dendritic cells, and pathogen recognition receptors. Immunol Res. 2004;29:187–196. doi: 10.1385/IR:29:1-3:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouhiainen A, Tumova S, Valmu L, Kalkkinen N, Rauva H. Pivotal advance: analysis of proinflammatory activity of highly purified eukaryotic recombinant HMGB1 (amphoterin) J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:49–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a cytokine and therapeutic target. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8:469–472. doi: 10.1179/096805102125001091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain A, Akanchha S, Rajeswari MR. Stabilization of purine motif DNA triplex by a tetrapeptide from the binding domain of HMGB1 protein. Biochimie. 2005;87:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCauley MJ, Zimmerman J, Maher LJ, 3rd, Williams MC. HMGB binding to DNA: single and double box motifs. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:993–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myint KM, Yamamoto Y, Doi T, Kato I, Harashima A, Yonekura H, Watanabe T, Shinohara H, Takeuchi M, Tsuneyama K, Hashimoto N, Asano M, Takasawa S, Okamoto H, Yamamoto H. RAGE control of diabetic nephropathy in a mouse model: effects of RAGE gene disruption and administration of low-molecular weight heparin. Diabetes. 2006;55:2510–2522. doi: 10.2337/db06-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu D, Young J, Song D, Esko JD. Heparin sulfate is essential for high mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1) signaling by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41736–41744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruan BH, Li X, Winkler AR, Cunningham KM, Kuai J, Greco RM, Nocka KH, Fitz LJ, Wright JF, Pittman DD, Tan XY, Paulsen JE, Lin LL, Winkler DG. Complement C3a, CpG oligos, and DNA/C3a complex stimulate IFN-α production in a receptor for advanced glycation end product-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2010;185:4213–4222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byles V, Chmilewski LK, Wang J, Zhu L, Forman LW, Faller DV, Dai Y. Aberrant cytoplasm localization and protein stability of SIRT1 is regulated by PI3K/IGF-1R signaling in human cancer cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:599–612. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koshikawa N, Hayashi J, Nakagawara A, Takenaga K. Reactive oxygen species-generating mitochondrial DNA mutation upregulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha gene transcription via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt/protein kinase C/histone deacetylase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33185–33194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–825. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.