Abstract

Mitochondria are the major supplier of cellular energy in the form of ATP. Defects in normal ATP production due to dysfunctions in mitochondrial gene expression are responsible for many mitochondrial and aging related disorders. Mitochondria carry their own DNA genome which is transcribed by relatively simple transcriptional machinery consisting of the mitochondrial RNAP (mtRNAP) and one or more transcription factors. The mtRNAPs are remarkably similar in sequence and structure to single-subunit bacteriophage T7 RNAP but they require accessory transcription factors for promoter-specific initiation. Comparison of the mechanisms of T7 RNAP and mtRNAP provides a framework to better understand how mtRNAP and the transcription factors work together to facilitate promoter selection, DNA melting, initiating nucleotide binding, and promoter clearance. This review focuses primarily on the mechanistic characterization of transcription initiation by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae mtRNAP (Rpo41) and its transcription factor (Mtf1) drawing insights from the homologous T7 and the human mitochondrial transcription systems. We discuss regulatory mechanisms of mitochondrial transcription and the idea that the mtRNAP acts as the in vivo ATP “sensor” to regulate gene expression.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA transcription, mitochondrial RNA polymerase, Rpo41, Mtf1

1. Introduction

The primary function of the mitochondria in the eukaryotic cells is to synthesize ATP. Hydrolysis of ATP releases energy that can be enzymatically coupled to drive biochemical reactions of the metabolic pathways. Mitochondria are indispensable organelles of eukaryotic cells because they also play important roles in processes such as cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, signaling, and innate immunity [1-5]. There is mounting evidence that dysfunctions in mitochondria are responsible for many neurological and muscular degenerative diseases as well as pathologies associated with human aging [6, 7]. Many of these mitochondrial (mt) related diseases are associated with defects in normal ATP production caused either by mutations in mt DNA itself or mutations in nuclear-encoded proteins that maintain the integrity of mt DNA [8-11]. These inherited diseases are thought to be as frequent as 1 in 4000 individuals, but they are difficult to diagnose due to wide range of symptoms and lack of reliable screening methods [12].

The mt genome is a circular double-stranded DNA that is widely believed to have originated from an ancient invasion by an α-proteobacterium–like ancestor into an archaea type host [13-15]. The mt DNA genome sizes vary greatly among various organisms, ranging from the one of the smallest 16.5 kb intron-less human mt genome to the much larger 75 kb yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae mt (Ymt) genome. Despite different genome sizes, the primary function of mt DNA is to code for proteins that synthesize ATP via the oxidative phosphorylation pathway and for components of mitochondrial ribosome. Mitochondria are not self-sufficient however and they depend on the nuclear DNA. A large number of proteins for ATP synthesis and all of the proteins required for mt DNA maintenance, including components of mt DNA replication, transcription, and repair are encoded by the nuclear DNA, and the proteins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and imported into the mitochondria.

The transcriptional machinery of mitochondria is distinct from the nuclear. The mt transcriptional machinery is much simpler and consists of two or three components: the mt RNA polymerase (mtRNAP) and one or two accessory transcription factors. The mtRNAP shows sequence and structural similarity to the bacteriophage T7/T3 class of single-subunit RNAPs [16, 17]. However, unlike phage RNAPs that catalyze all the steps of transcription without requiring any accessory factors [18], the mtRNAP depends on accessory transcription factors for initiation [19-21]. Since multi-subunit RNAPs, which transcribe bacterial and nuclear genomes also rely on accessory transcription factors [22-25], the mtRNAPs provide a mechanistic link between single and multi-subunit RNAPs. This leads to interesting questions on the evolution of mt transcription.

Much of our understanding of the mechanism and regulation of mt DNA transcription, including that of human mt DNA, is derived from studies of Ymt transcription. Biochemical studies of Ymt transcription are facilitated by the simpler two-component organization of Ymt transcription machinery and the genetic studies by the ease of creating and screening mutants in yeast. The two components of the Ymt transcription machinery, Rpo41 (the catalytic mtRNAP component) and Mtf1 (transcription factor) are homologous to human POLRMT and TFB2M, respectively [26-29], and sufficient for catalyzing transcription in vitro [30]. However, human mt transcription requires TFAM, a homolog of Ymt Abf2 protein [31], which both activates and regulates transcription by POLRMT-TFB2M complex [32].

The focus in this review is on recent structural and biophysical studies of mt transcription and comparisons to the mechanisms of T7 RNAP. Experimental evidence presented here primarily addresses the Ymt transcription machinery with parallels drawn from the players of the homologous human mt transcription. Mitochondrial DNA transcription has been a topic of many excellent and comprehensive reviews [19, 33-35]. Comparison of mtRNAP and T7 RNAP provides a better understanding of the roles of mtRNAP and transcription accessory factors. We discuss similarities and differences between the RNAPs of the two in promoter DNA recognition, discrimination against non-promoter DNA sequences, promoter melting, nucleotide binding, and promoter clearance. Mitochondrial transcription is known to play a key role in regulating mt gene expression, especially in response to changing ATP levels. We discuss a model that postulates that the Ymt transcriptional machinery serves as the in vivo ATP “sensor” to regulate gene expression in mitochondria.

2. Mitochondrial DNA transcriptional machinery

2.1. The mitochondrial RNA polymerase

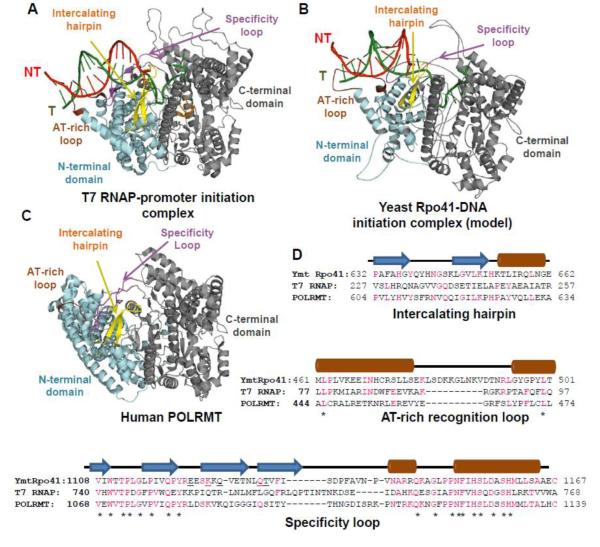

The mtRNAP protein can be divided into several domains including the C-terminal domain, N-terminal domain, and N-terminal extension based on amino acid sequence similarity to the single-subunit T7 RNAP. A homology model of Ymt Rpo41, was created from sequence and structural similarity to T7 RNAP-promoter complex (Fig. 1A, B) [36, 37]. This remarkable similarity between Rpo41 and T7 RNAP was confirmed by the recently determined crystal structure of human POLRMT (218-1230 region, Fig. 1C) [38]. The C-terminal domain of Rpo41 (~800 aa from a total of 1351 aa) shows 49-77% sequence identity in 8 regions to the C-terminal domain of T7 RNAP (~740 aa from a total of 883 aa), and this type of similarity is generally observed for other mtRNAPs [16, 37, 39]. The N-terminal domain (~200 aa) has low sequence similarity, but the crystal structure of POLRMT shows that parts of it are structurally similar to the N-terminal domain of T7 RNAP. The N-terminal extension (~250 aa) is the most variable region in mtRNAPs and it is completely missing in T7 RNAP.

Figure 1. Comparison of single-subunit RNAP structures from phage T7 and mitochondria.

(A) The crystal structure of T7 RNAP-promoter initiation complex (PDB 1QLN). (B) Modeled structure of yeast mt Rpo41 (PDB Rpo41_IC) with DNA from 1QLN [36]. (C) Crystal structure of human POLRMT without DNA (PDB 3SPA). The conserved C-terminal domains are shown in grey and the N-terminal domains in cyan, NT: non-template strand, and T: template strand. The promoter binding elements: AT-rich recognition loop (brown) and intercalating hairpin (yellow) in the N-terminal domain, and promoter specificity loop (purple) in the C-terminal domain are highlighted. Parts of the missing intercalating hairpin (aa 592-602) and specificity loop (aa 1086-1105) in human POLRMT are constructed based on structural alignment with T7 RNAP using PyMol. (D) Sequence alignment generated from structural homology of Rpo41 with T7 RNAP [36] and POLRMT with T7 RNAP [38]. Secondary-structure elements predicted using PSIPRED (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred) are depicted above the sequences as brown cylinders for α-helices, blue arrows for β-strands, and black lines for loops. Identical residues are denoted in pink, and the conserved ones are marked with an asterisk. Mutations in the specificity loop of Ymt Rpo41 which affect selective promoter utilization are underlined [37, 42].

2.1.1 The C-terminal domain of mtRNAP

The C-terminal domain of mtRNAPs (~800 aa) contains the elements to bind the template DNA, NTP, and Mg2+ and contains the catalytic site for the nucleotidyl transfer reaction to make RNA. The human POLRMT structure shows that this domain resembles a right hand with palm, thumb, and fingers subdomains (Fig. 1A-C), which are conserved elements in Pol-A family polymerases. A unique feature of T7 RNAP in this family of polymerases is the presence of specific insertions in the fingers subdomain that aid in sequence specific recognition of the promoter sequence. T7 RNAP contains a prominent insertion in the fingers subdomain called the promoter specificity loop, which forms an antiparallel β-ribbon that inserts into the major groove of the promoter DNA, where it makes base-specific interactions with -7 and -8 positions [40, 41]. Sequence and structure alignments have identified promoter specificity loops in Rpo41 and POLRMT, and biochemical studies with Rpo41 have confirmed its role in promoter recognition. Mutational and chemical-nuclease studies indicate that the promoter specificity loop in Rpo41 (1127-1149, Fig. 1D) binds the Ymt promoter between -1 to -8 [36, 37]. Residues in the promoter specificity loop, namely Glu-1224, Lys-1127, Gln-1135, Gln-1129 and Thr-1136, are crucial for promoter-specific transcription, and the latter two amino acids interact with the -7 position of the Ymt promoter [37, 42]. Many of the amino acids in the proposed promoter specificity loop of POLRMT (1086-1105, Fig. 1D) are missing in the crystal structure [38]. It may indicate that the promoter specificity loop assumes a defined structure only in the presence of the promoter DNA.

The fingers subdomain of T7 RNAP contains a second insertion called the fingers flap. The fingers flap domain has been proposed to interact with the non-template strand in the initiation and elongation complex [43, 44]. Although, its function is not completely defined, the fingers flap has been proposed to aid promoter melting during initiation and to control processivity during elongation [45, 46]. Sequence alignment shows that the fingers flap region is missing in Rpo41 [36]. Based on the finding that Mtf1 interacts with the non-template strand, an interesting possibility was suggested that Mtf1 adopts the role of fingers flap region in promoter melting (section 4).

2.1.2. The N-terminal domain of mtRNAP

The N-terminal domain of mtRNAP (~200 aa) shows moderate sequence similarity to the N-terminal domain of T7 RNAP. The N-terminal domain of T7 RNAP contains several elements that bind to the promoter in the initiation complex. Two specific elements, the AT-rich recognition loop and the intercalating hairpin, interact with the T7 promoter in the initiation complex [44, 47]. The AT-rich recognition loop binds into the minor groove of the upstream promoter region between -13 and -17 causing a slight bend in the DNA. The tip of the intercalating hairpin acts as a wedge and positions at the single-stranded/double-stranded junction between -4 and -5 to stabilize the melted promoter [40, 48]. Homology modeling and crystal structure have identified such elements in Rpo41 and human POLRMT [36-38]. The intercalating hairpin (Rpo41:617-630; POLRMT:610-620) appears to be important in promoter melting because deletion of five residues at the tip of the intercalating hairpin in POLRMT inactivates transcription from duplex but not pre-melted promoter [38]. The function of the AT-rich recognition loop (Rpo41: 481-497; POLRMT: 450-470, Fig. 1D) is less clear as single mutations in this region do not affect transcription by POLRMT [38].

2.1.3. The N-terminal extension of mtRNAP

The N-terminal extension (~300 aa) of mtRNAP is the most variable region among various species and it is not present in T7 RNAP. It contains the signal peptide for targeting into mitochondria, which is cleaved off after import by mitochondrial processing peptidases. Deletion of 1-100 or -185 aa in the N-terminal extension of Rpo41 has little effect on Ymt transcription, in vitro or in vivo [39, 49]. Remarkably, deletion of 1-270 aa in Rpo41 increases the efficiency of in vitro transcription by reducing abortive synthesis without affecting synthesis of the full-length transcript [39]. Hence, it was proposed that the N-terminal extension of Rpo41 is autoinhibitory and its deletion relieves this effect. A larger deletion of 1-380 aa greatly decreases transcription from duplex promoter, but not from pre-melted promoter [39].

Based on these studies, it was proposed that the 270-380 region is important for promoter melting. Furthermore, protein-protein crosslinking studies showed the Rpo41 deletion mutants bind Mtf1 more weakly, and hence it was proposed that the N-terminal extension may be involved in interactions with Mtf1 [39]. However, direct interactions of the isolated N-terminal extension regions with Mtf1 could not be demonstrated [50], which could be because the isolated extension regions do not fold properly on their own. The crystal structure of POLRMT shows that the N-terminal extension closely associates with the N-terminal domain [38] and this association may be important for correct folding of the domains.

Several studies suggest that the N-terminal extension, especially the 1-185 aa, also plays a role that is distinct from transcription, such as coupling transcription with RNA processing and translation. This region was shown to mediate physical interactions with proteins involved in these downstream processes [51-53].

2.2. Mitochondrial transcription factors

The most intriguing aspect of mtRNAPs is their similarity to single-subunit T7 RNAP and yet their dependence on accessory transcription factors for promoter-specific initiation. The Ymt Rpo41 depends on Mtf1 and human POLRMT on TFB2M and TFAM for promoter-specific initiation [19, 28, 29, 32, 54-57]. The mt transcription factors Mtf1 and TFB2M function in a manner similar to the sigma factors of bacterial RNAP, but they are structurally unrelated to sigma factors [58]. The crystal structure shows that Mtf1 and the homologous TFB2M are related to RNA/DNA methyltransferases [59], which raises interesting questions on the evolutionary origins of the mt transcription factors.

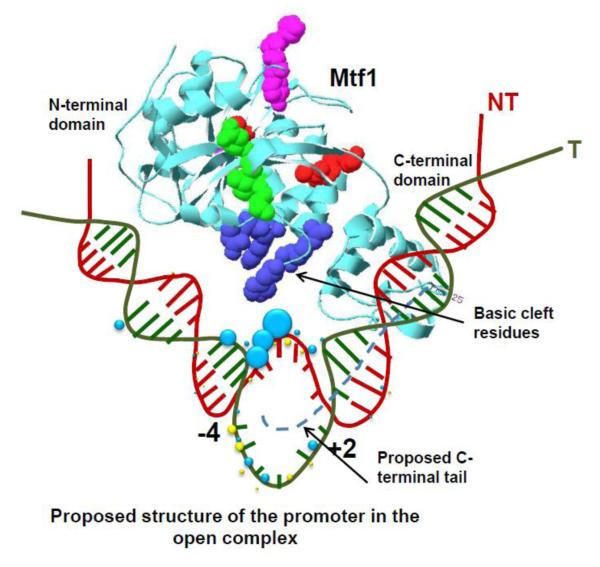

Mtf1 is a 43 kDa compact protein with two domains, N-terminal α/β domain and C-terminal helical domain, and a flexible C-terminal tail not resolved in the crystal structure [59] (Fig 2). The C-terminal tail plays a very important role as it interacts with the melted template strand in the open complex [60]. The N-terminal domain contains the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)–binding site found in methyltransferases; although, SAM binding is not essential for transcription [59, 61]. The two domains contain a basic cleft at the domain interface (Fig. 2) that might be involved in DNA binding. Residues in the basic cleft may aid in promoter melting, as mutations R178A/K179A and H187A/R189A in the basic cleft were shown to inactivate transcription on linear but not supercoiled DNA [62].

Figure 2. Mtf1 with the bent/open promoter DNA in the open complex.

Crystal structure of Mtf1 (grey, PDB 1I4W) positioned next to a model of bent/open promoter DNA in the open complex. Positions of Mtf1-DNA crosslinks (blue spheres) and Rpo41-DNA (yellow spheres) are shown [36]. The size of the spheres corresponds to the crosslinking efficiency. The C-terminal tail (dotted grey line) of Mtf1 is not present in the crystal structure and placed near the melted template strand in green [60]. Amino acids of Mtf1 known to result in loss of Rpo41 interactions are shown: Cluster A mutants Y42C, H44P, L53H (pink); cluster B mutants V135A, I154T, K157E (red); and cluster C mutants I221K, D225G, S218R [50, 83]. The amino acids in blue, R178, K179, H187, and R189, form a basic cleft at the two-domain interface and when mutated cause loss of activity on duplex but not premelted promoter .

2.3. Interactions between Rpo41 and Mtf1

Rpo41 forms a 1:1 complex with its accessory transcription factor Mtf1 and this was demonstrated both in the absence and in the presence of the promoter DNA [39, 63]. Protein-protein crosslinking studies provided Kd of 0.6 μM for Rpo41-Mtf1 complex in the absence of promoter and 0.4 μM in the presence of the Ymt promoter [39]. Deletion analyses however failed to identify a specific region of interaction between Rpo41 and Mtf1 and suggested instead that multiple regions are involved in protein-protein interactions [39,50]. Deletion of the C-terminal tail of Mtf1 (316-341) inhibits transcription and binding to Rpo41 [50], suggesting the C-terminal tail of Mtf1 may be involved in Rpo41 binding, in addition to its role in binding the template DNA [60].

Genetic screening identified several point mutants of Mtf1 that failed to interact with Rpo41 [50]. These point mutants cluster into three regions: Cluster A (Y42C, H44P, L53H), cluster B (V135A, I154T, K157E) and cluster C (S218R, I221K, and D225G). Mapping them on the crystal structure of Mtf1 shows their distribution on different faces of the protein (Fig 2). Many of the cluster A and B mutants modify residues that lie within the interior of Mtf1 protein. These amino acids may not directly interact with Rpo41, but may disrupt interactions with Rpo41 by causing local changes in Mtf1 structure. Region 210-225 is a good candidate for direct interactions with Rpo41, as the cluster C mutations in this region represent changes of surface exposed residues in Mtf1 protein.

Mutational studies also indicate that multiple regions of Rpo41 protein are involved in protein-protein interaction with Mtf1. Deletion analysis of Rpo41 indicates that the 270-380 region may mediate interactions with Mtf1 [39]. Similarly, a genetic suppressor screen using Mtf1/V135A mutant, which does not interact with Rpo41, identified three Rpo41 mutants (K1273A, A631V, E1124K) that restored interactions [64]. The location of these suppressor mutants in Rpo41 raises interesting possibilities of the promoter binding elements being involved in Rpo41-Mtf1 interactions. The A631 lies within the intercalating hairpin loop, E1124 in the promoter specificity loop, and K1273 in the extended foot. It will be interesting to determine whether Mtf1 interacts directly with these promoter binding elements or the mutations reorganize specific regions of Rpo41 that interact with Mtf1.

3. Mechanism of Transcription initiation

The general mechanism of DNA transcription is conserved in single-subunit and multi-subunit RNAPs from phage to human. Transcription takes places in three general stages of initiation, elongation, and termination. During initiation, the RNAP locates the promoter with or without the transcription factors. Once the RNAP is bound to the promoter, a specific region of the DNA is melted either by the RNAP itself, as in T7 RNAP, or by the RNAP and initiation transcription factors, as in multi-subunit RNAPs or mtRNAPs. In the resulting open complex, the transcription start site is melted and positioned deep within the catalytic site, where it directs sequence specific RNA synthesis. Binding of +1 and +2, priming and incoming NTPs, respectively, initiates 2-mer RNA synthesis by the nucleotidyl transfer reaction. During initiation, the RNAP makes short RNA products from 2-12 nt that dissociate into solution as abortive products. RNAP escapes abortive initiation after synthesis of 9-12 nt RNA, after which RNAP enters into the elongation stage, where RNA synthesis is highly processive, until termination.

3.1. Promoters of the yeast mitochondria

The mt promoters contain a consensus sequence that is recognized by the mt transcription machinery. The Ymt promoter is relatively small (9 base pairs) (Table 1) compared to the promoter of T7 RNAP (19 base pairs). The 9 base pairs of the Ymt DNA promoter is AT-rich and represented by 5′-(-8)ATATAAGTA(+1) non-template sequence, where +1 is the transcription start site [65, 66]. There are 28 conserved promoters in Ymt DNA (Table 1) that direct the synthesis of seven proteins of the ATP synthesis complex, two ribosomal RNAs (21S and 14S), 24 transfer RNAs, RNA-subunit of mt RNase P, and one ribosomal protein [67]. The Ymt genes are transcribed at different rates, and strong promoters have 15-20 times more activity than the weak promoters [68]. The nucleotide at position +2 plays a key role in dictating the strength of the Ymt promoters (Table 2). Promoters with a purine at +2 and a pyrimidine at +3 position in the non-template strand are strong promoters, whereas promoters containing a pyrimidine at +2 and purine at +3 are much weaker [68, 69].

Table 1. Yeast mitochondrial promoters.

The −8 to +3 consensus non-template promoter sequence of the Ymt promoter for the natural variants and tested base changes [67]. The acceptable changes are in green and those leading to defective transcription are in red. The ones in yellow are positions where transcription is fully restored with sequence-specific dinucleotide primer [71].

| Yeast mitochondrial DNA promoters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural variants | −8 | −7 | −6 | −5 | −4 | −3 | −2 | −1 | +1 | +2 | +3 |

| 15S rRNA, COX I, Oli-1, oril, ori2, ori3, ori5 | A | T | A | T | A | A | G | T | A | A | T |

| 21S rRNA | G | ||||||||||

| COX II | T | A | G | ||||||||

| Oli-2 | T | A | |||||||||

| tRNA(fMet), tRNA(Phe), tRNA(Ala) | T | ||||||||||

| tRNA(Glu) | A | G | |||||||||

| tRNA(Thr-CUN) | T | G | |||||||||

| tRNA(Thr-ACN) | G | T | A | ||||||||

| tRNA(Cys) | T | T | A | ||||||||

| RPM1 | T | A | G | A | |||||||

| Single mutations | |||||||||||

| A | A | A | A | ||||||||

| T | T | T | T | ||||||||

| G | G | G | |||||||||

| C | C | C | |||||||||

| Multiple mutations | |||||||||||

| −1/+2 | A | G | |||||||||

| −1/+1 | A | G | |||||||||

| −1/+1 | G | G | |||||||||

| +1/+2 | G | G | |||||||||

| −5/+2 | A | G | |||||||||

| −3/−1 | G | A | |||||||||

| −5/−1 | A | G | |||||||||

| −3/−1 | G | G | |||||||||

| −4/−2 | A | G | A | ||||||||

| −5/−3/−1 | A | G | G | ||||||||

Table 2. Regulation of yeast mitochondrial transcription by ATP.

The table compiles studies of Ymt promoters showing correlation between transcript amounts, sequence of +1 and +2 nucleotides and their Km values. The fold change in absolute transcript abundance in cells grown under repressing conditions (glucose medium) and de-repressing conditions (galactose medium) correlate with the Km of initiating NTPs [86, 87, 90].

| Promoter | +1+2 | Transcript amount relative to 15S rRNA (promoter strength) |

Absolute transcript amount (copies/cell) |

Derepressed /repressed |

Km ATP (μM) |

Km GTP (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repressed | Derepressed | ||||||

| 21S rRNA | AG | 0.9 | 2000 | 9000 | 2.8 | 9 | 25 |

| COX2 | AG | - | - | - | 3.8 | 15 | 57 |

| 15S rRNA | AA | 1 | 2200 | 9600 | 4.2 | 35 | 1.5 |

| tRNA (glu) | AA | 0.27 | 600 | 3200 | 5.3 | 53 | 2 |

|

ATP9

(Oli-1) |

AA | 0.06 | 130 | 480 | 6.7 | 58 | 7 |

|

COX1

(Oxi-3) |

AA | 0.03 | 65 | 300 | 8.2 | 68 | 23 |

| tRNA (cys) | AT | 0.013 | 30 | 240 | 6.6 | 140 | 17.5 [190 μM for UTP] |

Mutational studies have identified acceptable and non-acceptable changes in the Ymt promoter sequence from -7 to +1 [5′TAT(/a)AA(/g/c)GT(/a/c)N(+1), where lower case letter represents acceptable base changes] (Table 1) [65, 66, 69]. Non-acceptable changes fall into two categories. Mutations (−3, −1, +l, +2) around the transcription start site inactivate transcription, but the activity can be restored when reactions are supplied with dinucleotide primers [70, 71]. On the other hand, mutations (-7C, -6G, -4A, and -2A) inactivate transcription, but these cannot be reactivated by dinucleotides. The G:C base pairs at - 2 is obligatory and its change to any other base pairs completely inactivates transcription [72]. Interestingly, the highly conserved A:T base pair at +1 can be changed to any base pair without greatly affecting transcription [73].

3.2. Mechanism of promoter selection

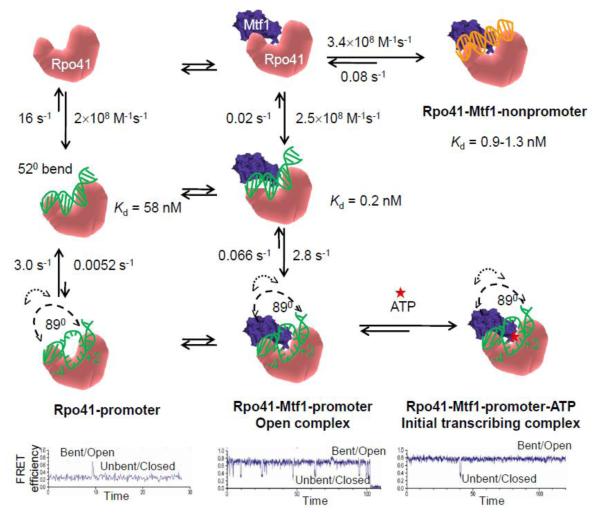

All RNAPs initiate transcription at specific sites on the genome, but the mechanism of promoter selection varies depending on the RNAP. The single-subunit T7 RNAP employs a relatively simple mechanism of promoter selection, wherein it discriminates against non-promoter sequences at the initial binding step. T7 RNAP binds its promoter sequences with an affinity that is ~105 fold tighter compared to its affinity for the non-promoter sequence [74]. Rpo41-Mtf1 employs a different strategy for promoter selection [75]. Rpo41 by itself binds DNA, but it binds both promoter and non-promoter sequences with similar affinities. The dissociation constant (Kd) of Rpo41 complex with promoter or non-promoter sequence is 55-65 nM. The selectivity for binding the promoter sequence is increased in the presence of Mtf1, but the degree of selectivity is modest. The Kd of Rpo41-Mtf1 complex with the promoter sequence is 0.2 nM and with the non-promoter sequence is 0.7-1.3 nM. The difference in DNA binding affinities between promoter and non-promoter sequences by Rpo41-Mtf1 is only 3-6 fold, which is extremely small, compared to the selectivity of 105 fold by T7 RNAP. Thus, Rpo41-Mtf1 does not use differential DNA binding affinity as the mechanism for promoter selection. Studies suggest that Rpo41-Mtf1 uses an induced-fit mechanism for promoter selection [75].

The induced-fit mechanism involves selective bending/melting of the promoter DNA, and these conformational changes are not observed in non-promoter sequences. Many RNAPs bend the promoter DNA to lower the activation energy for promoter melting. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) studies show that Rpo41 by itself bends the promoter DNA by ~52° (Fig. 3), but it also bends the non-promoter DNA to the same degree [75]. This degree of DNA bending is observed in the closed complex of T7 RNAP wherein the DNA is not melted [76]. Hence, the modest bending is not sufficient for DNA melting and to form a competent open complex. Remarkably, addition of Mtf1 caused the promoter DNA to severely bend by ~90°, and interestingly, this severe bending was not observed in the non-promoter sequences (Fig. 3) [75]. This severe ~90° bending angle is observed in the open complex of T7 RNAP wherein the promoter is melted. Thus, Rpo41-Mtf1 catalyzes promoter-specific initiation by an induced-fit mechanism, in which specific interactions of the two proteins with the promoter are used to bend and melt the DNA.

Figure 3. Kinetic mechanism of promoter binding, bending, and melting.

First column: Rpo41 (pink) binds the promoter DNA (green) and induces modest DNA bending. The single-molecule FRET time course (bottom panels) shows an example of the infrequent event of Rpo41-induced promoter DNA bending/opening. Second column: Rpo41-Mtf1 binds the promoter DNA more tightly and induces a sharp bend in the DNA that leads to a bent/open DNA with a much longer lifetime. The single-molecule time course shows an example of a more stable bent/open state in the presence of Mtf1. The time trace in the third column shows that the initiating ATP (red star) further stabilizes the bent/open state of the promoter bound to Rpo41-Mtf1. Third column, top panel, shows Rpo41-Mtf1 binding to the non-promoter DNA without bending it [75, 81].

3.3. Promoter bending and melting

Similar to T7 RNAP [40, 41, 77], Rpo41-Mtf1 melts the promoter DNA from -4 to +2. This was demonstrated using 2-aminopurine (2-AP) modified promoters [78]. 2-AP is a fluorescent adenine analog, whose fluorescence intensity is highly sensitive to base stacking interactions with the neighboring bases in the DNA. The fluorescence of 2-AP is quenched when the base is stacked with the neighboring bases in the duplex DNA and the fluorescence is enhanced when the base is unstacked as in the melted DNA [79, 80]. 2-AP substitutions in the -4 to +2 region of the Ymt promoter resulted in enhanced fluorescence intensity upon addition of Rpo41-Mtf1 [78]. However, fluorescence increase was not observed when individual adenines either upstream from -5 or downstream from +3 were substituted with 2-AP.

Single molecule FRET experiments show that the promoter DNA undergoes repeated bending and unbending transitions both in the presence of Rpo41 alone and Rpo41-Mtf1 [81]. In the presence of Rpo41 alone, the promoter remains mostly in the unbent state, but with a low frequency it shows transitions to the severely bent state (Fig. 3). Because DNA bending and opening are coupled processes [75], these results indicate that Rpo41 by itself has the ability to melt the promoter DNA. However, the bent/open state of promoter with Rpo41 alone has a very short lifetime, which explains why Rpo41 by itself is not capable of catalyzing promoter-specific initiation.

The DNA opening and closing transitions by Rpo41 and Rpo41-Mtf1 were quantified to determine the promoter opening and closing rate constants [81]. These studies provided new understanding of the role of Mtf1 in promoter melting, and indicated that Mtf1 not only stabilizes the melted promoter but also nucleates promoter melting. The rate constant of promoter opening with Rpo41 alone is very slow (0.0052 s−1) and promoter closing is fast (3.0 s−1). In the presence of Mtf1, the promoter closing rate constant decreased by ~45-fold (0.066 s−1). This indicates that Mtf1 aids promoter melting by stabilizing the bent/open conformation of the promoter DNA. Furthermore, in the presence of Mtf1, the promoter opening rate constant increased by ~500-fold (2.8 s−1), which indicates that Mtf1 plays an active role in melting the DNA by lowering the activation energy for destabilizing the DNA base pairs. The ratio of rate constants for promoter opening and closing with and without Mtf1 indicates that Mtf1 uses ~5 kcal/mol of binding free energy to stabilize the melted promoter [81].

4. Architecture of the Rpo41-Mtf1-promoter open complex

A variety of biochemical studies indicate that both Rpo41 and Mtf1 interact with the promoter DNA. However, high resolution structures of the RNAP complex with DNA are lacking and hence the detailed interactions of the promoter with mtRNAP or the transcription factors are not known. Mtf1 on its own does not bind promoter DNA [54, 78]; however, protein-DNA crosslinking studies indicate that it make direct interactions with the promoter in the ternary complex with Rpo41 [36, 60]. In fact, Mtf1 appears to bind across the entire length of the consensus sequence and to interact with both the upstream and downstream promoter region from -10 to +2. Since Mtf1 is a small protein, the bending of the promoter DNA most likely facilitates simultaneous interactions of Mtf1 with the upstream and downstream promoter regions (Fig 2).

Mtf1 appears to interact with both the melted DNA region of the promoter and the upstream duplex region. Prominent Mtf1-DNA crossslinks were observed with the −2 to −4 nucleotides of the non-template strand, which becomes single-stranded in the open complex. Similarly, Mtf1 crosslinks were observed with −8 to −10 nucleotides of the template DNA, which remains duplexed in the open complex [36]. The modeled promoter in Rpo41 shows that the two regions lie on one face of the promoter suggesting that Mtf1 may bind to one face of the DNA. In addition to binding the non-template strand, Mtf1 also binds to the melted template strand. The C-terminal tail (325-341) of Mtf1 contacts the -3/-4 bases of the melted template strand [60]. Since the melted template strand must be buried deep in the active site of Rpo41 as in T7 RNAP, the C-terminal tail of Mtf1 must insert into the active site and also interact with Rpo41 (Fig. 2). Overall, the interactions of Mtf1 with the promoter DNA are consistent with the role of Mtf1 in promoter recognition and DNA melting. The human Mtf1 homolog, TFB2M, was proposed to interact with the promoter DNA near the transcription start site. Two regions were proposed to be involved in these interactions, one at the extreme N-terminus between residues 1 and 42 and another between residues 43 and 59 [57].

The promoter DNA also contacts the Rpo41 as Rpo41-DNA crosslinks were observed across the entire length of the promoter [36]. This is consistent with the proposal that Rpo41 itself contains promoter binding elements, of which the promoter specificity loop has been demonstrated to interact with the -1 to - 8 consensus region [37, 64]. Although, Rpo41 does not catalyze promoter-specific initiation on duplex promoter, it is able to catalyze sequence specific initiation from pre-melted promoters created by introducing base changes in the non-template strand in the −4 to +2 or −2 to +2 region [60, 82]. A non-promoter bubble DNA is not transcribed; hence, it appears that Rpo41 may also recognize the promoter sequence by itself especially when the promoter is pre-melted. Overall, the architecture of Rpo41-Mtf1-DNA complex in the open complex suggests that the two components work cooperatively during promoter recognition and DNA melting.

5. Initiating NTP binding and transcription regulation

Melting of the promoter DNA to form the open complex exposes the +1 and +2 template bases that bind to the priming (+1) and incoming (+2) NTPs, respectively. Both initiating NTPs need to be base-paired to the template in order for the RNAP to catalyze the nucleotidyl-transfer reaction between them to make the 2-mer RNA. There is evidence that the mt transcription factors Mtf1 and TFB2M facilitate binding of the initiating NTPs. A reactive group in the priming NTP was shown to crosslink to human TFB2M between residues 24 and 42 [57]. Similarly, several lines of evidence indicate that Mtf1 plays a role in binding the +2 NTP. For example, in a promoter that initiates with the sequence AA, the initiating ATP is bound more tightly by Rpo41 when Mtf1 is present [78]. Similarly, weakening Mtf1 binding by deleting 1-270 aa in Rpo41 increases the ATP Kd from 82 μM to 220 μM [39]. Finally, a specific mutation C192F/Mtf1 increases the +2 NTP Km by 10-fold compared to wild-type Mtf1 [83]. The C192/Mtf1 is not defective in binding Rpo41 but its location near the basic cleft residues (Fig. 2) suggests that it might be defective in promoter melting and hence indirectly affects the NTP Km. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that the C192F/Mtf1 has a lower ATP Km when the promoter is pre-melted [83].

The +1 and +2 NTPs typically have higher Km values compared to the elongating NTPs [84, 85]. This is observed with Rpo41-Mtf1 as well, which binds +1 and +2 NTPs more weakly than the elongating NTPs (Km < 5 μM). Most Ymt promoters initiate with ATP at +1 and contain ATP, GTP or UTP at the +2 position. Interestingly, the +2 NTP has a higher Km (~30-500 μM) than the +1 NTP (Km ~10-50 μM) [78, 86], which indicates that the +2 NTP binding may play a role in regulating the rate of transcription initiation. In fact, Ymt promoters are classified as strong or weak depending on the type of NTP that binds to the +2 position and the overall rate of transcription varies 15-20 fold between strong and weak promoters [69, 87, 88]. Strong promoters that bind ATP at +2 have the lowest NTP Km, followed by intermediate Km for +2 GTP, and weak promoters with T at +2 have the highest Km for UTP [86].

5.1. Mitochondrial RNA polymerase is an ATP sensor

It is known that ATP concentrations regulate mitochondrial gene expression. This regulation by ATP occurs at the stage of transcription and has been well-studied in the yeast. Yeast cells grown in glucose produce high levels of cytoplasmic ATP, which represses Ymt transcription. When glucose is substituted with non-fermentable glycerol for example, Ymt transcription is activated ~20-fold. This increase in Ymt transcript is mainly from increased RNA synthesis rates, as opposed to increase in mt DNA copy number or elevation of Rpo41 and Mtf1 expression. Moreover, different Ymt promoters respond to changes in ATP levels to varying degrees [89].

Studies by Jaehning and coworkers have shown that Rpo41-Mtf1 itself acts as the in vivo ATP sensor [86, 90]. They measured in vivo changes in Ymt transcript abundance as yeast growth was shifted from glucose to glycerol, and correlated these changes to in vitro sensitivity of Ymt promoters to ATP concentration or the Km of ATP. Ymt promoters with higher Km values for the priming ATP, like ATP9 and COX1 promoters, show a higher sensitivity to changing ATP levels (6-8 fold difference in transcript abundance between glucose and glycerol conditions). On the contrary, promoters like 21S rRNA or COX2 with lower ATP Km values are less sensitive and show only a 3-4 fold change in transcript abundance with changes in ATP levels. Thus, Rpo41-Mtf1 itself appears to respond to changing ATP levels in mitochondria by regulating its rate of transcription initiation, which affects the level of the Ymt transcripts.

It is interesting that most mitochondrial promoters initiate with ATP as the priming nucleotide [91]. Nevertheless, in vitro studies indicate that the +1 base pair in Ymt promoters can be substituted with any base pairs without affecting transcription [73]. Therefore, it appears that there is an evolutionary pressure to maintain ATP as the priming nucleotide. Perhaps the ATP “sensing” mechanism is the most efficient way to regulate mt transcription and gene expression in response to fluctuating in vivo ATP pools. These findings from studies of Ymt transcription lay the foundation to begin to understand the molecular basis for how ATP concentrations might also regulate human mt DNA transcription and gene expression under different physiological conditions.

6. Abortive RNA synthesis and transition into elongation

In addition to initiating NTP binding, transcription efficiency is also regulated by how efficiently the RNAP escapes the promoter to make the transition from initiation to elongation. During transcription initiation, the RNAP maintains its interactions with the promoter and hence repeatedly synthesizes and releases short abortive RNA products ranging in lengths from 2-12 nt. Escape from abortive synthesis occur after 9-12 nt RNA synthesis, and promoter release is a key step in this process of transition into the elongation stage [92]. Escape from abortive synthesis is often rate limiting and efficient transition is characterized by fewer abortive products and a higher ratio of productive to abortive RNAs. On a strong promoter, T7 RNAP typically undergoes 3-4 cycles of abortive events per productive event but on weaker promoters this ratio is higher [93, 94]. Similar to T7 RNAP, Rpo41-Mtf1 appears to undergo transition from initiation to elongation after 9-12 mer RNA synthesis [39, 78, 82, 95]. However, in vitro Rpo41-Mtf1 appears to be less efficient than T7 RNAP, as it undergoes on an average ~20 abortive events per productive event [39]. Interestingly, deletion of the N-terminal extension region 1-270 aa reduces abortive products without affecting full-length RNA synthesis and hence increases the productive to abortive RNA ratio by ~4-fold [39]. This increase in efficiency of transition is attributed to weaker interactions of the Rpo41 deletion mutant with Mtf1 which facilitates Mtf1 release. Mtf1 plays a major role in promoter binding and melting in the initiation complex, and analogous to the sigma factor of bacterial RNAP, Mtf1 is released from Rpo41-DNA after 9-12 nt synthesis [63].

Promoter release is coupled also to initial DNA bubble collapse, when the initially melted promoter region reanneals back to its duplex form. In T7 RNAP, the -4 to +2 region collapses back to its duplex form after promoter release and this might be the case with Rpo41-Mtf1, as both RNAPs generate similarly sized initial DNA bubbles. If the initial DNA bubble collapse is prevented in Rpo41 by using a pre-melted promoter with mismatches in -4 to +2 region, then RNA synthesis is inhibited beyond 8 nt. Interestingly, this inhibition is observed when Mtf1 is present, but not in its absence [39, 82]. Thus, if Mtf1 remains stably bound to the initially melted region of the promoter, bubble collapse is inhibited which in turn prevents efficient transition into elongation.

When the initial DNA bubble collapses back to its duplex form, the 5′-end of the nascent transcript is released from the RNA:DNA hybrid [92, 94, 96]. Typically, the peeled 5′-end of the RNA binds into an RNA-exit channel, which is a critical element of the RNAP that stabilizes the elongation complex and supports processive RNA synthesis during that stage. The core subunit of the bacterial RNAPs contains an RNA-exit channel, but it is blocked by the sigma factor in the initiation complex [58]. When the sigma factor is released from the initiation complex, the RNA exit-channel is exposed and becomes available to bind the nascent RNA transcript. In contrast T7 RNAP does not contain a preformed RNA-exit channel, but a channel is created from protein conformational changes after promoter release. The N-terminal domain of T7 RNAP undergoes a large conformational change after promoter release, which causes subdomain H and promoter specificity loop to come together in space to create the RNA-exit channel in T7 RNAP [44, 47, 97, 98].

Mitochondrial RNAPs contain features of both multi-subunit and single-subunit RNAPs, and therefore it will be interesting to determine whether mtRNAP contains a pre-existing RNA-exit channel, as in the multi-subunit RNAPs, or if the RNA-exit channel is created from conformational changes, as in T7 RNAP.

7. Concluding remarks

Last decade has witnessed an immense progress in unraveling the basic mechanisms of transcription initiation by the mitochondrial RNAPs through biochemical and structural studies of purified components. The crystal structure of the human POLRMT provides the first glimpse of the organization of the catalytic RNAP component and its strikingly close resemblance to bacteriophage T7 RNAP, which raises further interesting questions as to why the mitochondrial RNAPs require accessory transcription factors to catalyze promoter-specific initiation when T7 RNAP does it on its own. Although, we have a better understanding of the role of the accessory factors in transcription initiation, the mechanism and structural basis of promoter melting and start site selection remains to be determined. Further insights will come from additional structures, including the holoenzyme and ternary complex with the promoter DNA, which will provide the framework for biophysical analysis that can provide quantitative description and dynamics of the various steps of transcription.

At present, there is little knowledge of the rate-liming steps of transcription by mitochondrial RNAPs and how the transition from initiation to elongation occurs on the promoter. Biophysical methods such as single molecule FRET are mapping the conformational changes in promoter DNA by recording the dynamics through fluorescence changes due to DNA bending and unbending transitions. Such methods have great potential in mapping the dynamic conformational changes in the protein components of the RNAP machinery and to understand how the components assemble and dissemble as transcription proceeds along its various stages. Overall, there is a general lack of understanding of the steps of transcription elongation and termination, and how the DNA sequence and accessory factors regulate these post-initiation events. In coming years, we can expect a more detailed comprehension of not only the structural and functional relationships between the components of mitochondrial transcription machinery but also with the proteins involved in downstream process that couple transcription to translation, which will shed light on the regulation of gene expression in mitochondria.

Research Highlights.

Mitochondrial (mt) RNA polymerases (RNAP) serve as an intriguing link between single and multi-subunit RNAPs.

Although structurally similar to T7 RNAP, the mt RNAPs depend on accessory transcription factors.

Both components bind the promoter and work cooperatively to catalyze promoter-specific initiation.

Induced-fit mechanism involving DNA bending is employed to differentiate between promoter and non-promoters.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH grant RM51966 to S.S.P. We thank the Patel lab members for their research contributions and Guo-Qing Tang and Divya Nandakumar for stimulating discussions in laboratory meetings that helped shape this review. We thank Taekjip Ha and Hajin Kim for providing the figure showing single molecule FRET dynamics.

Abbreviations

- mtRNAP

mitochondrial RNAP, Ymt, Yeast mitochondrial

- Mtf1

Mitochondrial transcription factor 1

- nt

nucleotides

- aa

amino acids

- SAM

S-adenosyl-L-methionine

- Kd

Equilibrium dissociation constant

- FRET

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer

- 2-AP

2-Aminopurine

- Km

Michaelis-Menten constant

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Hock MB, Kralli A. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:177–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rehman J. Empowering self-renewal and differentiation: the role of mitochondria in stem cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:981–986. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0678-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martinou JC, Youle RJ. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mammucari C, Patron M, Granatiero V, Rizzuto R. Molecules and roles of mitochondrial calcium signaling. Biofactors. 2011;37:219–227. doi: 10.1002/biof.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].West AP, Shadel GS, Ghosh S. Mitochondria in innate immune responses, Nature reviews. Immunology. 2011;11:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2010;51:440–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oliveira MT, Garesse R, Kaguni LS. Animal models of mitochondrial DNA transactions in disease and ageing. Experimental gerontology. 2010;45:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shutt TE, Shadel GS. A compendium of human mitochondrial gene expression machinery with links to disease. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2010;51:360–379. doi: 10.1002/em.20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shadel GS. Expression and maintenance of mitochondrial DNA: new insights into human disease pathology. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1445–1456. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Park CB, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:809–818. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rotig A. Human diseases with impaired mitochondrial protein synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haas RH, Parikh S, Falk MJ, Saneto RP, Wolf NI, Darin N, Cohen BH. Mitochondrial disease: a practical approach for primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1326–1333. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lang BF, Gray MW, Burger G. Mitochondrial genome evolution and the origin of eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:351–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ. Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles. Science. 2004;304:253–257. doi: 10.1126/science.1094884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Masters BS, Stohl LL, Clayton DA. Yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase is homologous to those encoded by bacteriophages T3 and T7. Cell. 1987;51:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cermakian N, Ikeda TM, Cedergren R, Gray MW. Sequences homologous to yeast mitochondrial and bacteriophage T3 and T7 RNA polymerases are widespread throughout the eukaryotic lineage. Nucleic acids research. 1996;24:648–654. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Davanloo P, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Studier FW. Cloning and expression of the gene for bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1984;81:2035–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bonawitz ND, Clayton DA, Shadel GS. Initiation and beyond: multiple functions of the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Mol Cell. 2006;24:813–825. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schinkel AH, Groot Koerkamp MJ, Tabak HF. Mitochondrial RNA polymerase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: composition and mechanism of promoter recognition. Embo J. 1988;7:3255–3262. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang H, Sun W, Wang Z, Zhang J, Chen D, Murchie AI. Identification and characterization of the mitochondrial RNA polymerase and transcription factor in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:5119–5130. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Martinez E. Multi-protein complexes in eukaryotic gene transcription. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;50:925–947. doi: 10.1023/a:1021258713850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huang Y, Maraia RJ. Comparison of the RNA polymerase III transcription machinery in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human. 2001;29:2675–2690. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Murakami KS, Darst SA. Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Borukhov S, Severinov K. Role of the RNA polymerase sigma subunit in transcription initiation. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:557–562. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Matsunaga M, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Expression and purification of wild type and mutant forms of the yeast mitochondrial core RNA polymerase, Rpo41. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;35:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Levens D, Morimoto R, Rabinowitz M. Mitochondrial transcription complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1981;256:1466–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Falkenberg M, Gaspari M, Rantanen A, Trifunovic A, Larsson NG, Gustafsson CM. Mitochondrial transcription factors B1 and B2 activate transcription of human mtDNA. Nat Genet. 2002;31:289–294. doi: 10.1038/ng909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McCulloch V, Seidel-Rogol BL, Shadel GS. A human mitochondrial transcription factor is related to RNA adenine methyltransferases and binds S-adenosylmethionine. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1116–1125. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1116-1125.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shutt TE, Lodeiro MF, Cotney J, Cameron CE, Shadel GS. Core human mitochondrial transcription apparatus is a regulated two-component system in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12133–12138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910581107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Diffley JF, Stillman B. A close relative of the nuclear, chromosomal high-mobility group protein HMG1 in yeast mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:7864–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shutt TE, Bestwick M, Shadel GS. The core human mitochondrial transcription initiation complex: It only takes two to tango. Transcription. 2011;2:55–59. doi: 10.4161/trns.2.2.14296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Clayton DA. Transcription and replication of mitochondrial DNA. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(Suppl 2):11–17. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.suppl_2.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jaehning JA. Mitochondrial transcription: is a pattern emerging? Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Asin-Cayuela J, Gustafsson CM. Mitochondrial transcription and its regulation in mammalian cells. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Paratkar S, Patel SS. Mitochondrial transcription factor Mtf1 traps the unwound non-template strand to facilitate open complex formation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:3949–3956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nayak D, Guo Q, Sousa R. A promoter recognition mechanism common to yeast mitochondrial and phage t7 RNA polymerases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:13641–13647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900718200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ringel R, Sologub M, Morozov YI, Litonin D, Cramer P, Temiakov D. Structure of human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Nature. 2011;478:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Paratkar S, Deshpande AP, Tang GQ, Patel SS. The N-terminal domain of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase regulates multiple steps of transcription. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:16109–16120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cheetham GM, Jeruzalmi D, Steitz TA. Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase-promoter complex. Nature. 1999;399:80–83. doi: 10.1038/19999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cheetham GM, Steitz TA. Structure of a transcribing T7 RNA polymerase initiation complex. Science. 1999;286:2305–2309. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Matsunaga M, Jaehning JA. A mutation in the yeast mitochondrial core RNA polymerase, Rpo41, confers defects in both specificity factor interaction and promoter utilization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:2012–2019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tahirov TH, Temiakov D, Anikin M, Patlan V, McAllister WT, Vassylyev DG, Yokoyama S. Structure of a T7 RNA polymerase elongation complex at 2.9 A resolution. Nature. 2002;420:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nature01129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yin YW, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the transition from initiation to elongation transcription in T7 RNA polymerase. Science. 2002;298:1387–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1077464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Guo Q, Nayak D, Brieba LG, Sousa R. Major conformational changes during T7RNAP transcription initiation coincide with, and are required for, promoter release. Journal of molecular biology. 2005;353:256–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Guo Q, Sousa R. Translocation by T7 RNA polymerase: a sensitively poised Brownian ratchet. Journal of molecular biology. 2006;358:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Steitz TA. The structural changes of T7 RNA polymerase from transcription initiation to elongation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Stano NM, Patel SS. The intercalating beta-hairpin of T7 RNA polymerase plays a role in promoter DNA melting and in stabilizing the melted DNA for efficient RNA synthesis. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;315:1009–1025. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wang Y, Shadel GS. Stability of the mitochondrial genome requires an amino-terminal domain of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8046–8051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cliften PF, Park JY, Davis BP, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Identification of three regions essential for interaction between a sigma-like factor and core RNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2897–2909. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Rodeheffer MS, Shadel GS. Multiple interactions involving the amino-terminal domain of yeast mtRNA polymerase determine the efficiency of mitochondrial protein synthesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:18695–18701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301399200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rodeheffer MS, Boone BE, Bryan AC, Shadel GS. Nam1p, a protein involved in RNA processing and translation, is coupled to transcription through an interaction with yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:8616–8622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009901200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Markov DA, Savkina M, Anikin M, Del Campo M, Ecker K, Lambowitz AM, De Gnore JP, McAllister WT. Identification of proteins associated with the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase by tandem affinity purification. Yeast. 2009;26:423–440. doi: 10.1002/yea.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Schinkel AH, Koerkamp MJ, Touw EP, Tabak HF. Specificity factor of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Purification and interaction with core RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1987;262:12785–12791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Xu B, Clayton DA. Assignment of a yeast protein necessary for mitochondrial transcription initiation. Nucleic acids research. 1992;20:1053–1059. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jang SH, Jaehning JA. The yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor, MTF1, is similar to bacterial sigma factors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:22671–22677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sologub M, Litonin D, Anikin M, Mustaev A, Temiakov D. TFB2 is a transient component of the catalytic site of the human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Cell. 2009;139:934–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vassylyev DG, Sekine S, Laptenko O, Lee J, Vassylyeva MN, Borukhov S, Yokoyama S. Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 A resolution. Nature. 2002;417:712–719. doi: 10.1038/nature752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schubot FD, Chen CJ, Rose JP, Dailey TA, Dailey HA, Wang BC. Crystal structure of the transcription factor sc-mtTFB offers insights into mitochondrial transcription. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1980–1988. doi: 10.1110/ps.11201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Savkina M, Temiakov D, McAllister WT, Anikin M. Multiple functions of yeast mitochondrial transcription factor Mtf1p during initiation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:3957–3964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.051003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cotney J, Shadel GS. Evidence for an early gene duplication event in the evolution of the mitochondrial transcription factor B family and maintenance of rRNA methyltransferase activity in human mtTFB1 and mtTFB2. J Mol Evol. 2006;63:707–717. doi: 10.1007/s00239-006-0075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Shadel GS, Clayton DA. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial transcription factor, sc-mtTFB, shares features with sigma factors but is functionally distinct. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2101–2108. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Mangus DA, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Release of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor from transcription complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:26568–26574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cliften PF, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Identifying a core RNA polymerase surface critical for interactions with a sigma-like specificity factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7013–7023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.7013-7023.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Biswas TK, Edwards JC, Rabinowitz M, Getz GS. Characterization of a yeast mitochondrial promoter by deletion mutagenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82:1954–1958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Schinkel AH, Groot Koerkamp MJ, Van der Horst GT, Touw EP, Osinga KA, Van der Bliek AM, Veeneman GH, Van Boom JH, Tabak HF. Characterization of the promoter of the large ribosomal RNA gene in yeast mitochondria and separation of mitochondrial RNA polymerase into two different functional components. Embo J. 1986;5:1041–1047. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Biswas TK. Nucleotide sequences surrounding the nonanucleotide promoter motif influence the activity of yeast mitochondrial promoter. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9693–9703. doi: 10.1021/bi982804l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wettstein-Edwards J, Ticho BS, Martin NC, Najarian D, Getz GS. In vitro transcription and promoter strength analysis of five mitochondrial tRNA promoters in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:2905–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Biswas TK, Getz GS. Nucleotides flanking the promoter sequence influence the transcription of the yeast mitochondrial gene coding for ATPase subunit 9. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83:270–274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Biswas TK, Getz GS. Regulation of transcriptional initiation in yeast mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:19053–19059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Biswas TK. Usage of non-canonical promoter sequence by the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Gene. 1998;212:305–314. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Biswas TK, Getz GS. A critical base in the yeast mitochondrial nonanucleotide promoter. Abolition of promoter activity by mutation at the -2 position. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:3927–3930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Biswas TK, Ticho B, Getz GS. In vitro characterization of the yeast mitochondrial promoter using single-base substitution mutants. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1987;262:13690–13696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bandwar RP, Patel SS. The energetics of consensus promoter opening by T7 RNA polymerase. Journal of molecular biology. 2002;324:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Tang GQ, Deshpande AP, Patel SS. Transcription factor-dependent DNA bending governs promoter recognition by the mitochondrial RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.261966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Tang GQ, Patel SS. T7 RNA polymerase-induced bending of promoter DNA is coupled to DNA opening. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4936–4946. doi: 10.1021/bi0522910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Bandwar RP, Patel SS. Peculiar 2-aminopurine fluorescence monitors the dynamics of open complex formation by bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:14075–14082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Tang GQ, Paratkar S, Patel SS. Fluorescence mapping of the open complex of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:5514–5522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807880200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Jean JM, Hall KB. Aminopurine fluorescence quenching and lifetimes: role of base stacking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:37–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011442198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Stivers JT. Aminopurine fluorescence studies of base stacking interactions at abasic sites in DNA: metal-ion and base sequence effects. Nucleic acids research. 1998;26:3837–3844. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kim H, Tang GQ, Patel SS, Ha T. Opening-closing dynamics of the mitochondrial transcription pre-initiation complex. Nucleic acids research. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Matsunaga M, Jaehning JA. Intrinsic promoter recognition by a “core” RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:44239–44242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Karlok MA, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Mutations in the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor, Mtf1, verify an essential role in promoter utilization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:28143–28149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Stano NM, Levin MK, Patel SS. The +2 NTP binding drives open complex formation in T7 RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:37292–37300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Lew CM, Gralla JD. Mechanism of stimulation of ribosomal promoters by binding of the +1 and +2 nucleotides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:19481–19485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Amiott EA, Jaehning JA. Sensitivity of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase to +1 and +2 initiating nucleotides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:34982–34988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Mueller DM, Getz GS. Transcriptional regulation of the mitochondrial genome of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:11756–11764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Biswas TK. Control of mitochondrial gene expression in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:9338–9342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Ulery TL, Jaehning JA. MTF1, encoding the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor, is located on chromosome XIII. Yeast. 1994;10:839–841. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Amiott EA, Jaehning JA. Mitochondrial transcription is regulated via an ATP “sensing” mechanism that couples RNA abundance to respiration. Mol Cell. 2006;22:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Tracy RL, Stern DB. Mitochondrial transcription initiation: promoter structures and RNA polymerases. Current genetics. 1995;28:205–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00309779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Martin CT, Esposito EA, Theis K, Gong P. Structure and function in promoter escape by T7 RNA polymerase. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. 2005;80:323–347. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bandwar RP, Jia Y, Stano NM, Patel SS. Kinetic and thermodynamic basis of promoter strength: multiple steps of transcription initiation by T7 RNA polymerase are modulated by the promoter sequence. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3586–3595. doi: 10.1021/bi0158472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Bandwar RP, Tang GQ, Patel SS. Sequential release of promoter contacts during transcription initiation to elongation transition. Journal of molecular biology. 2006;360:466–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Biswas TK. Transcriptional commitment of mitochondrial RNA polymerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of molecular biology. 1992;226:335–347. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90951-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Gong P, Esposito EA, Martin CT. Initial bubble collapse plays a key role in the transition to elongation in T7 RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:44277–44285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Steitz TA. Visualizing polynucleotide polymerase machines at work. EMBO J. 2006;25:3458–3468. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Turingan RS, Theis K, Martin CT. Twisted or shifted? Fluorescence measurements of late intermediates in transcription initiation by T7 RNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6165–6168. doi: 10.1021/bi700058b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]