Abstract

Background

A number of treatments have been shown to reduce the risk of postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease (CD). The optimal strategy is unknown. The aim was to evaluate the comparative cost-effectiveness of postoperative strategies to prevent clinical recurrence of CD.

Methods

Three prophylactic strategies were compared to “no prophylaxis”; mesalamine, azathioprine (AZA) / 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), and infliximab. The probability of clinical recurrence, endoscopic recurrence, and therapy discontinuation due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were extracted from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Quality-of-life scores and treatment costs were derived from published data. The primary model evaluated quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and cost-effectiveness at 1 year after surgery. Sensitivity analysis assessed the impact of a range of recurrence rates on cost-effectiveness. An exploratory analysis evaluated cost-effectiveness outcomes 5 years after surgery.

Results

A strategy of “no prophylaxis” was the least expensive one at 1 and 5 years after surgery. Compared to this approach, AZA/6-MP had the most favorable incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) ($299,188/QALY gained), and yielded the highest net health benefits of the medication strategies at 1 year. Sensitivity analysis determined that the ICER of AZA/6-MP was preferable to mesalamine up to a recurrence rate of 52%, but mesalamine dominated at higher rates. In the 5-year exploratory analysis, mesalamine had the most favorable ICER over 5 years ($244,177/QALY gained).

Conclusions

Compared to no prophylactic treatment, AZA/6-MP has the most favorable ICER in the prevention of clinical recurrence of postoperative CD up to 1 year. At 5 years, mesalamine had the most favorable ICER in this model.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, prophylaxis, decision analysis, cost-effectiveness

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that can often require surgical intervention due to complications such as strictures, fistulae, or perforation.1 Historically, 70% of patients require surgical resection within 10 years of initial CD diagnosis.2 Although surgery ostensibly leaves only healthy intestinal tissue behind, the majority of patients develop de novo mucosal inflammation at the anastomosis site. Endoscopic recurrence of CD is observed in >70% of patients within the first year, typically at the neoterminal ileum.3 The severity of endoscopic recurrence is predictive of subsequent clinical recurrence; 20% of patients show symptomatic recurrence within a year of endoscopic recurrence, and at least 50% experience clinical recurrence within 5 years.3,4

Given the morbidity associated with clinical CD recurrence after resection, a number of postsurgery treatments have been examined in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Mesalamine, azathioprine, metronidazole, and infliximab have all demonstrated efficacy in preventing clinical or endoscopic recurrence of CD after resection. Recent meta-analyses confirmed the superiority of azathioprine to placebo, and to mesalamine.5,6 However, azathioprine is associated with frequent discontinuation due to adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and its long-term use is associated with a risk of lymphoma.5,7 While mesalamine has a safer side-effect profile than azathioprine, it has only modest efficacy in postoperative prevention. In addition, adherence to mesalamine maintenance therapy is reported to be as low as 40%.8 Infliximab was highly effective in preventing endoscopic recurrence of CD in a small prospective RCT, but its long-term prophylactic use is also limited by safety and cost concerns.9,10

Unfortunately, no head-to-head comparative studies between the prophylactic strategies to prevent clinical recurrence (mesalamine, azathioprine, metronidazole, and infliximab) have been published. Therefore, the optimal strategy, in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness, remains unclear. In addition, the relative impact of ADRs and costs of each treatment strategy is unknown. Based on this lack of data, expert groups have been unable to make definitive recommendations.11

The Institute of Medicine identified Comparative Effectiveness Research as a “national priority” for the United States recently in an era of increasing concerns of the costs of healthcare.12 In light of this uncertainty, and implications, we undertook a comprehensive economic evaluation, from a societal perspective, to define the comparative cost-effectiveness of each treatment strategy in order to identify the optimal prophylactic therapy (compared to “no prophlyaxis”) to prevent CD recurrence in patients in the U.S. during the first year after intestinal resection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A decision analysis model was developed to compare the quality-of-life outcomes and cost-effectiveness of four different prophylactic treatment strategies for the prevention of clinical CD recurrence after intestinal resection. Monte Carlo simulation was used to facilitate a “head-to-head evaluation” of postsurgery prophylactic treatment strategies. The primary model evaluated outcomes (quality-adjusted life years [QALYs]) and costs for 1 year after surgery. In addition, additional exploratory analyses were undertaken to analyze costs and outcomes for 5 years after surgery and for the prevention of endoscopic, rather than clinical, recurrence. Results are reported in a manner consistent with consensus recommendations for this study type.13,14 Markov modeling was not performed due to the lack of suitable data on transition probabilities for the postoperative patient population.

Model Structure

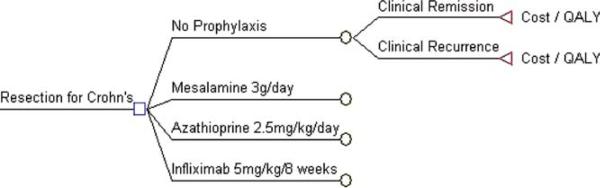

In the primary model, a hypothetical cohort of adult patients who have undergone intestinal resection for CD (N = 100,000) commenced one of four CD prophylactic strategies 2 weeks after surgery (model start): no treatment, mesalamine (3 g/day), azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/day) or infliximab (5 mg/kg induction and 5 mg/kg maintenance every 8 weeks) (Fig. 1). As per clinical practice, mesalamine and azathioprine were assumed to be given as continuous daily oral therapy, while infliximab was given with induction doses at 0, 2, and 6 weeks and then maintenance therapy every 8 weeks. Consistent with average patient characteristics in RCTs of CD prophylactic therapy after resection, the mean age of the cohort was 35 years and the duration of disease prior to surgery was <10 years (see Supporting Table 1).5

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of the four treatment options, and the reported outcomes, examined in this decision analysis. QALY, quality-adjusted life years.

The time horizon of the primary model was 1 year after starting postsurgery prophylactic therapy because RCT data are only available for this time period for all strategies.5 At the end of 1 year, patients were assumed to be in one of two clinical states: 1) remained in clinical remission throughout the entire year, or 2) had experienced clinical recurrence at some point during the year. Given the young average age of the cohort, and the fact that any surgical mortality occurs prior to the model start, mortality risks were assumed to be the same for all four prophylaxis strategies and were not specifically modeled. No RCT has reported “mean time to clinical recurrence” data in those patients who experience recurrence within the 1st year after surgery.5 Therefore, for the purposes of costs and QALY estimations, and based on the clinical experience of the authors (A.S.C., A.C.M.), all recurrences were assumed to occur halfway through the year (at the beginning of month 6).

All clinical recurrences were assumed to be moderately severe (Crohn's Disease Activity Index score [CDAI] of 249), based on criteria for clinical recurrence used in the trials.15 Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI score <150. Once clinical recurrence occurred, patients were assumed to receive treatment with the next agent in step-up therapy for the remaining duration of the time horizon. Patients who developed recurrence on mesalamine switched to azathioprine, those on azathioprine to infliximab, and those on infliximab to adalimumab, as per standard practice.11

In the model, patients who experienced an adverse drug reaction (ADR) with one agent were switched to an alternative agent, with the order of agents following standard clinical practice algorithms (Supporting Fig. 1).11 Based on the clinical experience of the authors (A.S.C., A.C.M.), ADRs were assumed to occur by the end of the first month of exposure to an agent. Patients started the alternative agent at the beginning of the subsequent month. ADRs reported in clinical trials with postoperative mesalamine, azathioprine, or infliximab were mostly mild, reversible, and similar across agents.5 Therefore, cost and quality of detriments associated with ADRs were assumed to be similar for all four strategies.

The model was constructed using a decision analysis software program (TreeAge Pro Suite 2009, Williamstown, MA).

Probability of Events

The probability estimates for events are summarized in Table 1. The probability of clinical recurrence and ADRs with no treatment, mesalamine, or azathioprine (AZA) / 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) were derived from a meta-analysis of RCTs investigating these strategies to prevent postoperative CD recurrence (Supporting Table 1).5 This meta-analysis evaluated five trials comparing mesalamine to placebo (N = 688), four trials comparing mesalamine to AZA/6-MP (N = 389), and one trial comparing AZA/6-MP to placebo (N = 81). Point estimates were obtained from the average probability from all of the relevant trials, unless the test for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis was significant.5

TABLE 1.

Primary Model Assumptions

| Parameter | Baseline | Range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of clinical recurrence | |||

| No therapy | 0.37 | 0.11-0.66 | Doherty |

| Mesalamine | 0.27 | 0.23-0.29 | Doherty |

| Azathioprine / 6MP | 0.18 | 0.16-0.22 | Doherty |

| Infliximab | 0.09 | 0.05-0.15 | Reguiero |

| Probability of ADR | |||

| No therapy | 0 | 0 | |

| Mesalamine | 0.08 | 0.07-0.09 | Doherty |

| Azathioprine / 6MP | 0.18 | 0.16-0.19 | Doherty |

| Infliximab | 0.1 | 0.05-0.15 | Reguiero, Hanauer |

| Treatment costs over 12 months ($) | |||

| No therapy | $ — | $ — | |

| Mesalamine | $ 5,235 | $ 3490-8103 | AWP |

| Azathioprine / 6MP | $ 2,700 | $ 1435-4172 | AWP |

| Infliximab | $ 25,937 | $ 16422-45944 | AWP & CPT codes, Wu |

| Adalimumab | $ 21,418 | $ 10,380-25967 | AWP, Sussman |

| Medical service-related costs for active | $ 5,346 | $ 530-12932 | Kapelman, Malone |

| Crohn's disease p.a. | |||

| Quality-of-life utilities | |||

| Clinical remission (CDAI<150) | 0.88 | 0.84-0.96 | Gregor |

| Clinical remission after 1 -2 ADRs | 0.87 | 0.83-0.95 | Gregor, Chung, Expert Opinion |

| Clinical recurrence (CDAI 249) | 0.78 | 0.61-0.89 | Gregor |

| Clinical recurrence after 1 ADR | 0.77 | 0.67-0.95 | Gregor, Chung, Expert Opinion |

| Clinical recurrence after 2 ADRs | 0.76 | 0.68-0.96 | Gregor, Chung, Expert Opinion |

In contrast, the probability of clinical recurrence for infliximab was obtained directly from the only published trial in this setting (N = 24). However, due to the small size of the prophylactic infliximab study, the probability of ADRs was derived from the ACCENT 1 trial, which evaluated maintenance treatment with infliximab (N = 573).9,16

The probability of ADRs for patients receiving no treatment was assumed to be zero. Treatment discontinuation due to nonadherence or reasons other than ADRs were assumed to be similar for all strategies over 1 year, and therefore were not specifically modeled. All probabilities were assumed to be additive.

Utility Scores

Quality-of-life utility scores for clinical remission and clinical recurrence were drawn from published Standard Gamble data derived from a cohort of 180 patients with CD (Table 1).17 The utility score for clinical remission (CDAI score 129) was 0.88 and utility score for clinical recurrence (CDAI score = 249) was 0.78.17,18 Based on published data, and the authors’ experience (A.C.M., A.S.C.), each ADR was assumed to decrease utility scores by 0.01.19

Cost of Prophylactic Strategies

The baseline costs of standard follow-up for a patient after resection was assumed to be similar regardless of which treatment was subsequently used. Due to the temporary and mostly mild nature of ADRs, their costs were assumed to be similar for all strategies and were not included. Therefore, differences in postresection costs were driven by the cost of prophylactic treatment, and the cost of managing a clinical recurrence of CD only.

The costs associated with each prophylactic strategy were estimated by methods similar to those employed by previous similar studies and are reported in 2010 dollars20,21 (Table 1). The annual cost of branded mesalamine (at doses of 3 g/day), generic and branded azathioprine (dosed at 2.5 mg/kg/day for an average weight of 75 kg) and infliximab and adalimumab were calculated from average wholesale prices (AWP) from the “Red Book,” 2010.22 Infliximab drug costs were based on a dose of 5 mg/kg for a 75 kg patient requiring four vials per infusion and receiving eight infusions in the first year (three dose induction and maintenance every 8 weeks), also from Red Book, 2009.22,23 In addition, costs associated with a 2-hour infusion of infliximab were estimated from average Medicare billing costs for CPT codes 96413 and 96415 in 2010.24 Costs of outpatient adalimumab was also obtained from the Red Book and published data.25 The medical service-related costs (2010 dollars) of managing patients with active CD was calculated from published data.26,27 These costs include hospitalizations and outpatient visits, but not medication costs. The costs of managing a clinical recurrence therefore included costs of initial prophylactic therapy to time of recurrence, then medical service costs of active disease, and medication costs of next therapeutic agent for the duration of the time horizon (Supporting Table 2). Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERS) were calculated prior to rounding, and after exclusion of dominated strategies.

Discounting

The primary model evaluated outcomes and costs over 1 year. Therefore, costs and QALYs were not discounted for the 1-year model

Sensitivity Analysis

One-way sensitivity analyses were performed to test the strength of observed differences by testing extreme values of each variable. The range of recurrence and ADR probabilities were drawn from the minimum and maximum values in the published literature and expert opinion (A.S.C., A.C.M.) (Table 1). We performed threshold analyses to determine the values of key variables that would yield costs per QALY gained of $50,000 and $100,000 (acceptability frontier).

Monte Carlo: Trial Microsimulation

Finally, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation (100,000 iterations) that accounted simultaneously for the uncertainties in the model inputs. We constructed distributions for the input variables based on the available data, as described above, and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were produced.

Exploratory Analysis

Clinical trial data in this setting beyond 1 year is not available for all treatment strategies to allow a Markov Model. Therefore, an exploratory analysis was undertaken to provide a preliminary evaluation of the 5-year costs and QALYs associated with prophylactic therapy after surgery for CD. The costs and QALY assumptions were similar to the primary model, but the impact of ADRs was not included in this model due to lack of data on ADRs over this time frame (Supporting Table 3). The recurrence rates over 5 years with each strategy were derived from published studies, and clinical recurrence was assumed to occur at 30 months after surgery in this model. Five-year averages for QALYs and costs of treatment of active CD were obtained from the literature.17,26,27 Costs and QALYs were discounted at 3% per year and are reported in 2009 dollars. Sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo simulations were undertaken as described for the primary model.

In addition, since endoscopic recurrence is more common than clinical recurrence in the first year after surgery, we also performed an exploratory model of these strategies to prevent endoscopic recurrence. Since utility scores and medical care costs for endoscopic recurrence (independent of symptoms) have not been described, we used the assumption that patients with significant endoscopic recurrence (Rutgeerts score >i2) would incur similar costs and impact on quality-of-life as those with clinical recurrence (Supporting Table 4). The literature suggests that these patients will subsequently develop clinical recurrence.3

RESULTS

Model Outcomes

In the primary model the QALYs were highest after 1 year of infliximab (0.87), followed closely by azathioprine (0.86), mesalamine (0.85), and no therapy (0.84). In the 5-year exploratory analysis, infliximab was associated with higher total QALYs (3.7 QALYs/5 years, or 0.74 QALYS/year) when compared with no treatment (3.6 QALYs/5 years, or 0.71 QALYs/year). The costs of treatment and management of clinical recurrence with the infliximab strategy over 1 year ($25,127) and 5 years ($112,165) were substantially higher than the next most costly strategy (azathioprine; $6692 at 1 year and $43,709 at 5 years).

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

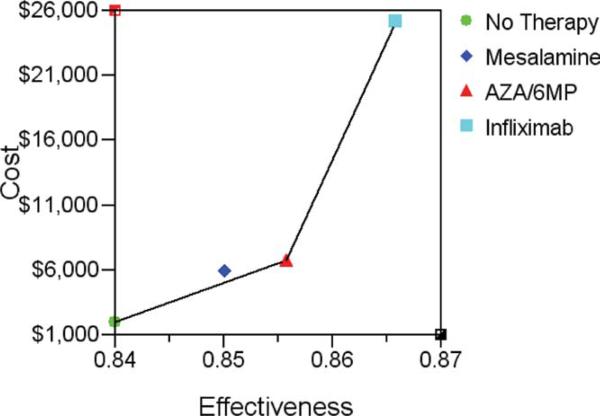

In the primary 1-year model, a strategy of “no prophylaxis” was the least expensive approach to prevent clinical or endoscopic recurrence, and the baseline for all drug comparisons ($2,321/QALY) (Table 2). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), or costs per QALY gained was $299,188 for AZA/6-MP, and $1,831,912 for infliximab. Azathioprine was the most cost-effective medication strategy over 1 year, when compared to “no prophylaxis” (Fig. 2). When endoscopic recurrence (>i2) was used as the outcome in the model, azathioprine remained the most cost-effective medication strategy ($7552/QALY) providing a more favorable ICER than mesalamine or infliximab over 1 year (Supporting Table 5).

TABLE 2.

Cost-effectiveness Analysis at Year 1

| Strategy | Costs* | Incr Cost | QALY | Change in QALYs | $ / QALY | Incr C/E (ICER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No therapy | $1,957 | 0.84 | — | $/QALY 2,321 | — | |

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | $3,948 | 0.85 | 0.01 | $/QALY 6,921 | — |

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | $787 | 0.86 | 0.01 | $/QALY 7,792 | $/QALY 299,188 |

| Infliximab | $25,127 | $18,435 | 0.87 | 0.01 | $/QALY 28,918 | $/QALY 1,831,912 |

Costs of drug and disease recurrence.

FIGURE 2.

Graph of cost-effectiveness of the four strategies examined over year 1 in the primary model. Costs are measured in 2009 U.S. dollars, effectiveness in QALYs. The connecting line segment between strategies defines the cost-effective frontier or set of possibly optimal choices.

In the exploratory 5-year model, a strategy of “no prophylaxis” was also the least expensive approach (Table 3). The ICER for mesalamine ($244,177 per QALY gained) dominated AZA/6-MP, and had a lower cost than infliximab ($2,303,318 per QALY gained).

TABLE 3.

Cost-effectiveness Analysis at Year 5

| Strategy | Cost | Incr Cost | QALYs | Change in QALYs | $ / QALY | Incr C/E (ICER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No therapy | $6,081 | . | 3.55 | — | $ 1,713 | — |

| Mesalamine | $24,639 | $18,558 | 3.63 | 0.08 | $ 6,795 | $ 244,177 |

| AZA / 6MP | $43,709 | $19,071 | 3.59 | -0.04 | $ 12,182 | (Dominated) |

| Infliximab | $112,165 | $87,526 | 3.66 | 0.04 | $306,131 | $ 2,303,318 |

*Costs of drug and disease recurrence.

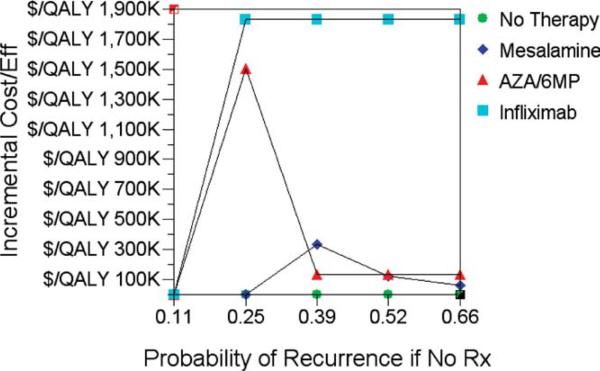

One-way Sensitivity Analysis: Probability of Recurrence, Rate of ADRs

The key question in postoperative CD recurrence prevention is whether different strategies should be adopted for patients based on their probability of postoperative recurrence. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis of cost-effectiveness in the primary model across a range of recurrence probabilities for the “no treatment” group. Azathioprine dominated mesalamine up to a clinical recurrence rate of 52%, but beyond this threshold mesalamine was the most cost-effective strategy (Table 4). As can be seen in Figure 3, the ICER for infliximab ($1.9M/QALY gained) remained stable up to a clinical recurrence rate of 66%, whereas the ICER for AZA/6-MP falls as the recurrence rate increases ($136,013/QALY gained if recurrence rate 66%), and is surpassed by mesalamine ($61,832/QALY gained if recurrence rate 66%). In one-way sensitivity analysis for azathioprine ADR rates and recurrence rates, azathioprine dominated mesalamine and had a lower ICER than infliximab, across a range of probabilities (data not shown). This included azathioprine ADR probabilities up to 20%. Even if the probability of recurrence over 1 year with infliximab was 0%, it had a higher ICER (less cost-effective) than azathioprine over this time frame ($1,043,386 vs. $296,220 per QALY gained).

TABLE 4.

One-way Sensitivity Analysis: Probability of Recurrence by Year 1

| Recurrence Rate | Strategy | Cost | Incr Cost | QALY | Change in QALY | $ / QALY | Incr C/E (ICER) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.11 | No therapy | $582 | 0.87 | $/QALY 669 | |||

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | 0.85 | $/QALY 6,922 | (Dominated) | |||

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | 0.86 | $/QALY 7,792 | (Dominated) | |||

| Infliximab | $25,127 | 0.87 | $/QALY 28,918 | (Dominated) | |||

| 0.25 | No therapy | $1,309 | 0.86 | $/QALY 1,531 | |||

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | 0.85 | $/QALY 6,922 | (Dominated) | |||

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | $5,383 | 0.86 | 0 | $/QALY 7,792 | $/QALY 1,505,192 | |

| Infliximab | $25,127 | $18,435 | 0.87 | 0.01 | $/QALY 28,918 | $/QALY 1,831,912 | |

| 0.39 | No therapy | $2,036 | 0.84 | $/QALY 2,420 | |||

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | 0.85 | $/QALY 6,922 | (Ext Dom) | |||

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | $4,656 | 0.86 | 0.02 | $/QALY 7,792 | $/QALY 268,708 | |

| Infliximab | $25,127 | $18,435 | 0.87 | 0.01 | $/QALY 28,918 | $/QALY 1,831,912 | |

| 0.52 | No therapy | $2,764 | 0.83 | $/QALY 3,339 | |||

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | $3,141 | 0.85 | 0.03 | $/QALY 6,922 | $/QALY 124,215 | |

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | $787 | 0.86 | 0.01 | $/QALY 7,792 | $/QALY 136,013 | |

| Infliximab | $25,127 | $18,435 | 0.87 | 0.01 | $/QALY 28,918 | $/QALY 1,831,912 | |

| 0.66 | No therapy | $3,491 | 0.81 | $/QALY 4,288 | |||

| Mesalamine | $5,904 | $2,414 | 0.85 | 0.04 | $/QALY 6,922 | $/QALY 61,833 | |

| AZA/6MP | $6,692 | $787 | 0.86 | 0.01 | $/QALY 7,792 | $/QALY 136,013 | |

| Infliximab | $25,127 | $18,435 | 0.87 | 0.01 | $/QALY 28,918 | $/QALY 1,831,912 |

FIGURE 3.

Results of sensitivity analysis for probability of CD recurrence with a strategy of ‘ no prophylaxis.’ Incremental cost-effectiveness (against baseline of ‘no prophylaxis’) is plotted against various rates of clinical recurrence.

In the 5-year model, the ICER of mesalamine dominated AZA/6-MP across a range of recurrence probabilities of clinical recurrence (Supporting Table 6). As the rate of recurrence climbed, the ICER of the mesalamine strategy declined inversely.

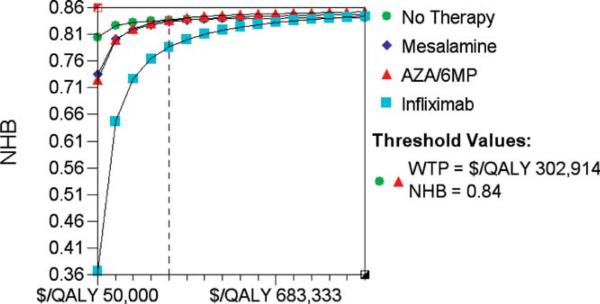

Monte Carlo Simulations and Cost-effectiveness Acceptability Curves

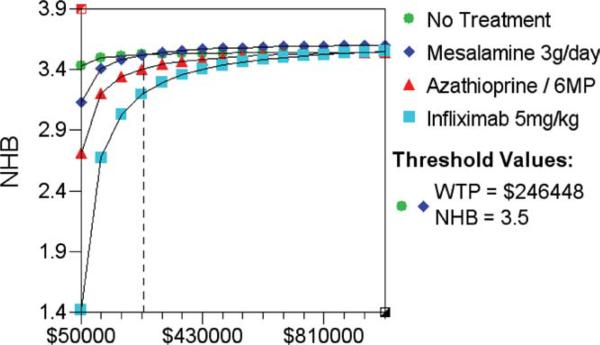

Monte Carlo discrete simulation was performed to explore the effects of variability that would occur if 100,000 “individuals” were to undergo this treatment strategy for the primary model. The ICER results for the Monte Carlo model were similar to the primary deterministic analysis; a strategy of “no prophylaxis” remained the least expensive approach to prevent clinical or endoscopic (>i2) recurrence (data not shown). When Net Health Benefits were plotted across a range of “willingness-to-pay” levels (WTP $50K to $100K), AZA/6-MP and mesalamine yielded superior “net health benefits” (0.79) to infliximab (0.61) up to a WTP level of $100,000. AZA/6-MP only produced similar net health benefits to “no prophylaxis” when the WTP threshold exceeded $300,000 over 1 year (clinical recurrence) (Fig. 4), or $117,000 (endoscopic recurrence) (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Results of Monte Carlo trials microsimulation in primary model. Net health benefits (NHB) are plotted against a range of ‘willingness to pay’ per QALY levels from $50,000 to $1,000,000. The threshold value at which AZA/6-MP is equivalent to ‘no prophylaxis’ is shown by the vertical dotted line.

In the 5-year model, the net health benefits with a strategy of “no prophylaxis” remained the least expensive, and mesalamine the most cost-effective medication strategy (Fig. 5). When net health benefits were plotted against a WTP range of $50 to $100K, the “no treatment” strategy provided superior health benefits. Only when the WTP was increased to $245,000 did mesalamine provide superior net health benefits up to a WTP ceiling of $1 million.

FIGURE 5.

Results of Monte Carlo trials microsimulation in the 5-year analysis. Net health benefits (NHB) are plotted against a range of ‘willingness to pay’ per QALY levels from $50,000 to $1,000,000. The threshold value at which mesalamine is equivalent to ‘no prophylaxis’ is shown by the vertical dotted line.

DISCUSSION

The majority of patients with CD require surgical resection at some stage in the course of their disease in order to maintain disease remission. Unfortunately, this trend that does not appear to have been impacted by primary anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy.28 Postoperatively, many patients develop symptomatic recurrence, some within months and at least 50% within 5 years of their surgery. Nitroimidazole antibiotics, mesalamine, and AZA/6-MP have demonstrated efficacy in preventing recurrence; however, their prolonged clinical utility is limited due to issues with adherence and tolerability.5 Although infliximab demonstrated efficacy in preventing clinical and endoscopic recurrence up to 2 years after surgery, the optimal duration of such a strategy is unclear.29

Interest is now focused on devising refined long-term strategies to maintain clinical remission after intestinal resection surgery by altering the natural history of CD in this setting. Our 1-year results suggest that AZA/6-MP is the most cost-effective treatment option compared to “no prophylactic therapy” to prevent either clinical or endoscopic recurrence. These results remained unchanged up to a background clinical recurrence rates for the no prophylactic therapy group of 52% at 1 year. Although infliximab was associated with the highest quality-of-life scores, the ICER for infliximab ($1.8 million/QALY) was significantly higher than standard intervention benchmarks, which range from $50,000 to 100,000/QALY.21 In addition, AZA/6-MP had the highest net health benefits over year 1, assuming a WTP of $50,000 to $100,000 per unit of effectiveness gained.21 Our exploratory analysis that extrapolated these outcomes to a 5-year time horizon concluded that mesalamine was the most cost-effective medication strategy over this time frame.

Whether all patients require prophylaxis postoperatively, or whether targeted prophylaxis can be adopted for “high-risk” patients, is hampered by a lack of validated prediction rules on who to “target.”30 Previous studies have convincingly identified only smoking and perforating disease phenotype as strong risk factors for disease recurrence.31,32 Other variables such as age of onset and duration of disease before surgery have yielded conflicting results.32 However, no prospective studies have tested different prophylactic strategies according to the baseline risk of disease recurrence, although such approaches have been proposed.33 A large retrospective study of 199 patients with CD reported that treating patients only after they developed endoscopic evidence of recurrence (“targeted treatment”) was associated with similar clinical recurrence rates to treating all patients (“immediate treatment”), although there may have been selection bias in targeted therapy by the treating physicians.34 Our results contribute to this debate by suggesting that AZA/6-MP remained the most cost-effective compared to “no prophylaxis” when recurrence rates for the “no prophylaxis” group ranged from 11%–52%; beyond this threshold mesalamine was more cost-effective.

Patients also appear to consider similar types of risks and benefits as included in our cost-effectiveness analysis. In one study by Kennedy et al,35 55% of patients presented with the option of postoperative maintenance therapy for CD reported that the type and severity of potential side effects were the most important consideration, while 36% considered efficacy to be the most important. The Kennedy et al study also found that patients’ treatment preferences were influenced by costs.34 Another study evaluating hypothetical health states found that subjects preferred mesalamine over no prophylaxis, despite the small relative risk reduction of CD recurrence (15%).36 The health state associated with taking mesalamine was favored beyond using no prophylaxis, despite the small relative risk reduction of recurrence (15%). These studies support our findings that cost and the patients’ risk tolerance for ADRs are important considerations in addition to the efficacy of postoperative prophylactic CD therapy.

The findings of our study must be considered in the context of its limitations. As with all decision analysis evaluations, the results are limited by the availability of relevant data. Published clinical trials have only reported data for a relatively short follow-up (12–24 months). Therefore, our primary model was limited to a 1-year time horizon. Our exploratory model of the impact of prophylactic strategies over 5 years is based on extrapolations of heterogeneous clinical data. General application is also limited by accuracy of the cost inputs for the model. For example, there are wide regional variations in the U.S. for infliximab infusion treatment costs. We maximized accuracy of cost inputs by using contemporary Red Book data and published costs from other recent studies. In addition, we performed sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of variability in input data. Finally, relevance to the community setting of this model may be limited by the fact that the recurrence data are drawn predominantly from trials in tertiary referral centers and by publication bias. However, generalizability is maximized through use of meta-analysis data. We also performed sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo microsimulation to account for variability in clinical practice. As discussed previously, sufficient data were not available to build a Markov model for the 5-year time horizon analysis. In addition, a time and motion study for detailed costing and assessment of productivity costs were beyond the scope of this study. The authors made every effort to obtain current cost data for the largest components of the cost of each therapy. Other limitations include no assumptions for discontinuation other than ADRs or recurrence, no difference in mortality between strategies, and assumptions that recurrence rates on therapy do not vary based on background rates. Finally, adherence is an issue in the maintenance of remission of colitis, and is also probably an issue in postoperative prevention of CD.8 There are no data published on adherence rates in this setting to determine probabilities. Recent data from the Mayo Clinic suggests similar nonadherence rates between mesalamine, azathioprine, and biologics based on pharmacy refills; therefore, inclusion of adherence probabilities is unlikely to significantly change the model outcomes.37

In conclusion, this model predicts that AZA/6-MP prophylactic therapy is the most cost-effective drug option compared to “no prophylaxis” in the primary 1-year model after surgery for CD. Mesalamine was more cost-effective in an exploratory 5-year model in the U.S. healthcare setting. Infliximab yielded marginally higher QALYs compared to all strategies, in this model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.C.M. is supported by K23DK08433 and the Dept. of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC); R.A.M. is supported by 5K23CA139005 and the Dept. of Medicine, BIDMC, and the Clinical Investigator Training Program: BIDMC, Harvard/MIT Health Sciences and Technology, in collaboration with Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Co. Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the article, or the decision to submit for publication. Conflict of Interest Disclosure: G.D. and R.M. have no competing interests to declare. A.C.M.: research funding (Proctor & Gamble, Shire and Salix), advisory board (UCB, Abbott), speaker's honorarium (Abbott, Schering-Plough). A.S.C.: speaker's honoraria (Proctor & Gamble, Centocor), advisory board (Abbott, UCB).

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

This article was published online on Sept. 8, 2011. A few errors were subsequently identified. This notice is included in the online and print versions to indicate that both have been corrected January 2012. A note is also at the end of the article, explaining the corrections.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

- The figures calculated in the original manuscript for 1-year ICERs (& Table 2) were not adjusted for exclusion of dominated strategies, which is why the exact $/QALY figures have changed for some ICERs. This has been clarified in the methods in the corrected paper.

- The phrase “most cost-effective” used in some sections to describe the results with “no prophylaxis” is more accurately described as “least expensive”. This is an important distinction for describing cost-effectiveness results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244–250. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1697–1701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, et al. Natural history of recurrent Crohn's disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665–672. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borley NR, Mortensen NJ, Chaudry MA, et al. Recurrence after abdominal surgery for Crohn's disease: relationship to disease site and surgical procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:377–383. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty G, Bennett G, Patil S, et al. Interventions for prevention of post-operative recurrence of Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD006873. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006873.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, Ardizzone S, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for the prevention of post-operative recurrence in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2089–2096. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, et al. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121–1125. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.049460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, et al. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2929–2933. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regueiro M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, et al. Infliximab prevents Crohn's disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:441–450. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ollendorf DA, Lidsky L. Infliximab drug and infusion costs among patients with Crohn's disease in a commercially-insured setting. Am J Ther. 2006;13:502–506. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000245223.43783.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465–483. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine . Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummond M, Manca A, Sculpher M. Increasing the generalizability of economic evaluations: recommendations for the design, analysis, and reporting of studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, et al. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:1339–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.16.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, et al. Ornidazole for prophylaxis of post-operative Crohn's disease recurrence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:856–861. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregor JC, McDonald JWD, Klar N, et al. An evaluation of utility measurements in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1997;3:265–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson PR, Weston AR, Shann A, et al. Relationship between disease severity, quality of life and health-care resource use in a cross-section of Australian patients with Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1306–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegner's granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1841–1848. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan GG, Hur C, Korzenik J, et al. Infliximab dose escalation vs. initiation of adalimumab for loss of response in Crohn's disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1509–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen EF, Kane SV, Ladabaum U. Cost-effectiveness of 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3094–3105. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Red Book: Pharmacy's Fundamental Reference. Thomson Reuters; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu EQ, Mulani PM, Yu AP, et al. Loss of treatment response to infliximab maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease: a payor perspective. Value Health. 2008;11:820–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CPT Code / Relative Value Search 2010 https://catalog.ama-assn.org/Catalog/cpt/cpt_search_result.jsp?requestid=2745105.

- 25.Sussman DA, Kubiliun N, Chao J, et al. Comparison of medical costs among patients using adalimumab or infliximab: a retrospective study (COMPAIRS). Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(Suppl 1):S436–S437. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malone DC, Waters HC, Van Den BJ, et al. A claims-based Markov model for Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:448–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones DW, Finlayson SR. Trends in surgery for Crohn's disease in the era of infliximab. Ann Surg. 2010;252:307–312. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e61df5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regueiro M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, et al. Two year post-operative follow-up of patients enrolled in the randomised controlled trial of infliximab to prevent recurrent Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:A522. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemann M. Review article: can post-operative recurrence in Crohn's disease be prevented? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(Suppl 3):22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avidan B, Sakhnini E, Lahat A, et al. Risk factors regarding the need for a second operation in patients with Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2005;72:248–253. doi: 10.1159/000089960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto T. Factors affecting recurrence after surgery for Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3971–3979. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swoger JM, Regueiro M. Postoperative Crohn's disease: how can we prevent it? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:501–504. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bordeianou L, Stein SL, Ho VP, et al. Immediate versus tailored prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic recurrences after surgery for ileocecal Crohn's disease? Surgery. 2011;149:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy ED, To T, Steinhart AH, et al. Do patients consider postoperative maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease worthwhile? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:224–235. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy ED, Detsky AS, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, et al. Can the standard gamble be used to determine utilities for uncertain health states? An example using postoperative maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease. Med Decis Making. 2000;20:72–78. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0002000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kane SV, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, et al. Limited clinical utility of a self-administered tool for predicting medication adherence behavior in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2011:140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.