Abstract

Peroxisomes carry out many essential lipid metabolic functions. Nearly all of these functions require that an acyl group – either a fatty acid or the acyl side chain of a steroid derivative – be thioesterified to coenzyme A (CoA) for subsequent reactions to proceed. This thioesterification, or “activation”, reaction, catalyzed by enzymes belonging to the acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) family, is thus central to cellular lipid metabolism. However, despite our rather thorough understanding of peroxisomal metabolic pathways, surprisingly little is known about the specific peroxisomal ACSs that participate in these pathways. Of the 26 ACSs encoded by the human and mouse genomes, only a few have been reported to be peroxisomal, including ACSL4, ACSVL1 (FATP2), and FATP4. In this review, we briefly describe the primary peroxisomal lipid metabolic pathways in which fatty acyl-CoAs participate. Then, we examine the evidence for presence and functions of ACSs in peroxisomes, much of which was obtained before the existence of multiple ACS isoenzymes was known. Finally, we discuss the role(s) of peroxisome-specific ACS isoforms in lipid metabolism.

Keywords: Peroxisome, Acyl-CoA synthetase, Lipid metabolism, Fatty acid activation

1. Introduction

When peroxisomes were first identified over a half-century ago, they were considered by some to be vestigial organelles with little physiological significance. Work done over the last three to four decades has clearly demonstrated otherwise. In particular, peroxisomes carry out many essential processes involving fatty acid (FA) metabolism.

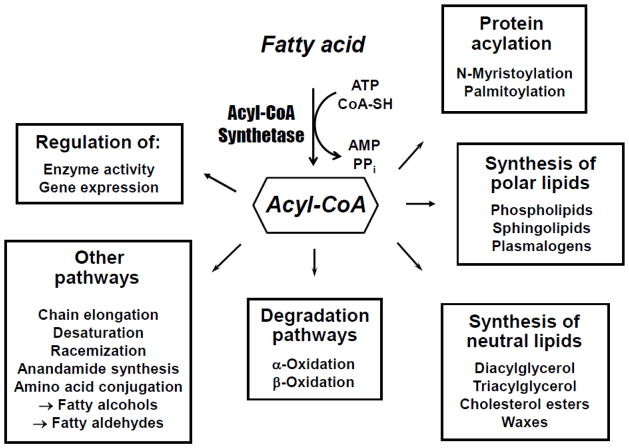

Essentially all cellular metabolic pathways in which FAs participate require that they first be activated to their CoA derivatives (Fig. 1). Among these pathways are the synthesis of triacylglycerol, phospholipids, plasmalogens, sphingolipids, and cholesterol esters, α-and β-oxidation of FA, FA elongation, conversion of FA to fatty alcohols, insertion and removal of double bonds, and protein acylation. Notable exceptions to the requirement for FA activation are the pathways for conversion of polyunsaturated FAs arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid to bioactive eicosanoids and docosanoids, respectively. In addition, some bacteria, yeast, and plants use FA-acyl carrier protein thioesters instead of acyl-CoAs for certain metabolic processes [1–3].

Fig. 1. Metabolic fates of activated FAs.

Most pathways of cellular FA metabolism require prior activation of the FA by thioesterification to CoA. The ACS isoform that participates in a specific pathway is frequently dependent upon the tissue, cell type, subcellular location, and FA chain length. In addition to the pathways illustrated, fatty acyl-CoAs can be degraded by thioesterases that cleave the FA:CoA bond, and by nudix hydrolases that cleave the pyrophosphate bond within the CoA moiety.

The ACS reaction is ATP-dependent. In the first half-reaction, the FA substrate is adenylated, releasing inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi):

The ubiquitous enzyme inorganic pyrophosphatase, which can be found in soluble, mitochondrial, peroxisomal, and other subcellular fractions [4], rapidly cleaves PPi, effectively preventing reversal of this reaction. In the second half-reaction, CoA displaces AMP, forming a thioester bond to yield the activated FA:

The length of FA carbon chains varies from 2 to more than 30, significantly affecting FA hydrophobicity and solubility. These factors likely influenced the evolution of distinct families of ACSs that activate short-, medium-, long-, and very long-chain FA substrates. This was nicely demonstrated more than 40 years ago by Aas, who measured rat liver mitochondrial and microsomal ACS enzyme activity with FA substrates ranging in chain length from 2–20 carbons [5]; four overlapping but distinct peaks of enzyme activity were observed. Although it was initially thought that there might be a single ACS responsible for activation of each FA chain length group, we now know the situation to be far more complex. Human and mouse genomes encode 26 ACSs [6], while the plant Arabidopsis thaliana has an estimated 64 acyl-activating enzyme genes [7].

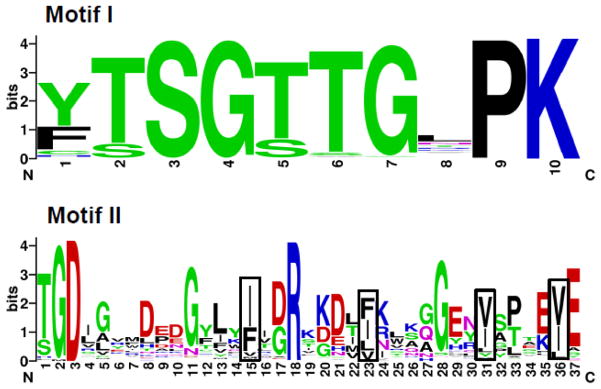

Identification of ACSs was facilitated by the recognition of two highly conserved domains; all enzymes with documented ACS activity contain these motifs (Fig. 2) [6, 8, 9]. This has allowed the identification of several new putative ACSs, and has facilitated the assignment of proteins to structurally-related subfamilies. Additional conserved domains found in some, but not all, ACS subfamilies have been identified. Twenty-two of the mammalian ACSs can be grouped into five subfamilies, which include the aforementioned short-, medium-, long-, and very long-chain activating enzymes, as well as a family containing two proteins homologous to the Drosophila melanogaster “bubblegum” protein [6]. Uniform ACS nomenclature has been established for four subfamilies, the short-chain (ACSS), medium-chain (ACSM), long-chain (ACSL), and bubblegum (ACSBG) families [10]; the mammalian genes/proteins are listed in Table 1. The six very long-chain ACS family genes are currently designated SLC27A1-6. Members of this subfamily were investigated as fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs) as well as ACSs; the official gene nomenclature (SoLute Carrier) reflects their putative transport function (Table 1). Four less structurally-related ACS enzymes are also represented in mammalian genomes.

Fig. 2. Conserved domains in ACSs.

Most ACS sequences contain 600–700 amino acids. All proteins known to have ACS enzymatic activity have two highly conserved motifs. Top. Motif I is a 10 amino acid sequence typically located 200–300 from the N-terminus. Motif I consensus: [YF]TSGTTGxPK. Motif I is an AMP-binding domain first described by Babbitt et al. [116]; mutations in this region decrease or abolish catalytic activity [117]. Bottom. Motif II contains 36–37 amino acids and the conserved arginine (R) at position 18 is always found approximately 260 residues downstream of Motif I [6]. Four positions where hydrophobic residues are found are enclosed in boxes. Motif II consensus: TGDxxxxxxxGxxxhx[DG]RxxxxhxxxxGxxhxxx[EK]hE. Weblogo version 2.8.2, located at weblogo.berkeley.edu, was used to generate sequence logos in which the height of each letter indicates the amino acid conservation at that position. Data from 137 human, mouse, zebrafish (Danio rerio), fruit fly (D. melanogaster), worm (C. elegans), and yeast (S. cerevisiae) ACS sequences described in [6] were used to generate the logos. In the consensus sequences, x is any amino acid, and h indicates a hydrophobic residue.

Table 1.

Acyl-CoA Synthetase Nomenclature.

| ACS Subfamily | Official Symbol | Official Name | Aliases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain | |||

| ACSS1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 1 | ACAS2L, AceCS2 | |

| ACSS2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2 | ACAS2, ACECS, ACS, ACSA | |

| ACSS3 | Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 3 | ||

| Medium-chain | |||

| ACSM1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 1 | BUCS1, MACS1 | |

| ACSM2a | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 2A | ACSM2 | |

| ACSM2b | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 2B | ACSM2, HXMA | |

| ACSM3 | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 3 | SA, SAH | |

| ACSM4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 4 | ||

| ACSM5 | Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 5 | ||

| Long-chain | |||

| ACSL1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1 | ACS1, FACL1, FACL2, LACS, LACS1, LACS2 | |

| ACSL3 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 | ACS3, FACL3 | |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 | ACS4, FACL4, LACS4 | |

| ACSL5 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 5 | ACS2, ACS5, FACL5 | |

| ACSL6 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 6 | ACS2, FACL6, KIAA0837, LACS 6, LACS2, LACS5 | |

| Very long-chain | |||

| SLC27A1 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 1 | ACSVL5, FATP, FATP1 | |

| SLC27A2 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 2 | ACSVL1, FACVL1, FATP2, VLACS, VLCS, hFACVL1 | |

| SLC27A3 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 3 | ACSVL3, FATP3, VLCS-3 | |

| SLC27A4 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 4 | ACSVL4, FATP4, IPS | |

| SLC27A5 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 5 | ACSB, ACSVL6, FACVL3, FATP5, VLACSR, VLCS-H2 | |

| SLC27A6 | Solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 6 | ACSVL2, FACVL2, FATP6, VLCS-H1 | |

| “Bubblegum” | |||

| ACSBG1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 1 | BG, BG1, BGM, GR-LACS, KIAA0631, LPD | |

| ACSGG2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase bubblegum family member 2 | BGR, BRGL | |

| Other | |||

| AACS | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase | ACSF1 | |

| ACSF2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase family member 2 | ||

| ACSF3 | Acyl-CoA synthetase family member 3 | ||

| AASDH | Aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | ACSF4 | |

In addition to FAs, other compounds containing acyl side chains are substrates for ACSs. For example, the final step in the synthesis of bile acids requires the removal of three carbons from the cholesterol side chain, converting 27-carbon precursors to 24-carbon mature bile acids [11]. In this process, a terminal carbon of the cholesterol aliphatic side chain is oxidized to a carboxylic acid, which must be activated to its CoA thioester before removal of a 3-carbon fragment via β-oxidation. Furthermore, many xenobiotic compounds, such as the hypolipidemic drug clofibrate and the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen, are ACS substrates [12]. Enzymes of the ACSM family are primarily responsible for xenobiotic activation [13]. Besides providing an acyl-CoA substrate for amino acid conjugation and elimination, xenobiotic-CoAs are substrates for lipid synthesis [12].

In addition to classifying ACSs by their substrate chain length preference, these enzymes have also been categorized by their subcellular locations. There are numerous literature references to a “mitochondrial medium-chain ACS” or a “microsomal long-chain ACS”, without designating a specific enzyme. Many of these studies were done prior to the genomic era, at a time when our understanding of the diversity of the ACS subfamilies was far more limited.

2. Peroxisomal pathways requiring activated FAs

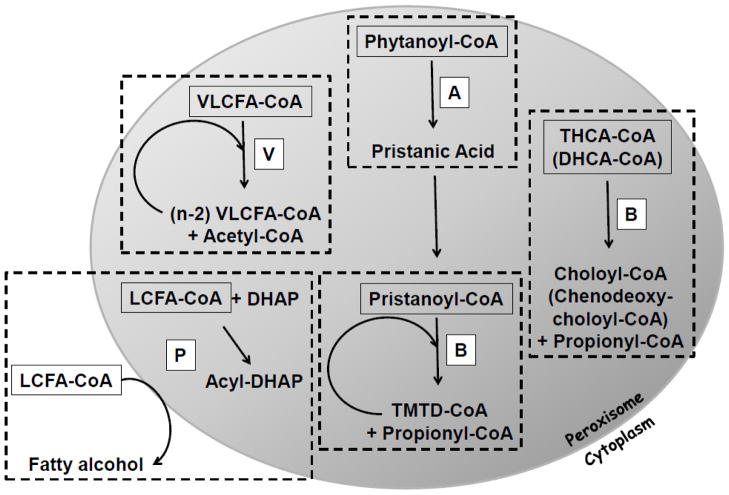

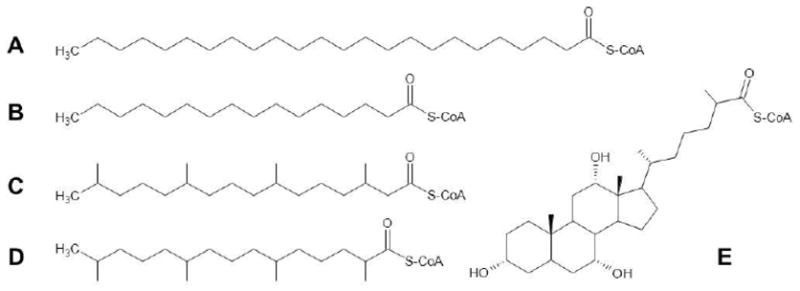

Because peroxisomal metabolic pathways are discussed in detail elsewhere in this special issue, they will be mentioned only briefly here. Peroxisomal reactions requiring acyl-CoA are depicted schematically in Fig. 3. Structures of peroxisomally relevant acyl-CoAs are depicted in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3. Peroxisomal reactions requiring acyl-CoA.

An acyl-CoA is required for several peroxisomal reactions. The pathways in which these reactions are found include VLCFA β-oxidation (V), branched-chain β-oxidation (B), α-oxidation (A), and plasmalogen synthesis (P). Racemization of R- and S-enantiomers of intermediates of the branched-chain β-oxidation pathways also require CoA thioesters (not illustrated). LCFA-CoA, long-chain fatty acyl-CoA; DHCA-CoA, dihydroxycholestanoyl-CoA; THCA-CoA, trihydroxycholestanoyl-CoA; TMTD-CoA, 4,8,12-trimethyltridecanoyl-CoA; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate.

Fig. 4. Structures of peroxisomally relevant acyl-CoAs.

Shown are the CoA derivatives of: A, the VLCFA, lignoceric acid (C24:0); B, the long-chain FA, palmitic acid (C16:0); C, the β-methyl branched-chain FA phytanic acid (3,7,11,15-tetramethyl hexadecanoic acid); D, the α-methyl branched-chain FA pristanic acid (2,6,10,14-tetramethyl pentadecanoic acid; and E, the bile acid precursor trihydroxycholestanoic acid.

2.1 β-Oxidation of very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFA)

Accumulation of VLCFA, particularly in the nervous system, is partly responsible for the pathologic manifestations seen in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy and disorders of peroxisome biogenesis [14]. Detoxification of excess VLCFA occurs via the chain-shortening peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway [14]. VLCFA must be activated to their CoA derivatives before being degraded by the sequential action of peroxisomal enzymes acyl-CoA oxidase, D- (or L-) bifunctional protein, and 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase. Both bifunctional enzymes catalyze enoyl-CoA hydratase and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activities. Products include acetyl-CoA and a shortened (by two carbons) acyl-CoA; the latter becomes the substrate for subsequent rounds of β-oxidation (Fig. 3). Whether VLCFA are activated intraperoxisomally or outside the peroxisome (and then transported into the organelle as VLCFA-CoA) has been the subject of some debate [15–19].

2.2 α-Oxidation of phytanic acid

Failure to degrade excess amounts of the dietary 3-methyl branched-chain FA, phytanic acid (3,7,11,15-tetramethyl hexadecanoic acid) causes Refsum disease, an adult-onset peripheral neuropathy [20]. Phytanic acid also accumulates in the peroxisome biogenesis disorders, and in rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata [21]. Because phytanic acid has a methyl group on the 3-carbon, it cannot be degraded by β-oxidation. Instead, a single carbon is removed by α-oxidation. Activation of this branched-chain FA to phytanoyl-CoA is a requisite first step (Fig. 3). The sequential action of peroxisomal enzymes phytanoyl-CoA hydroxylase and 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase release the carboxyl carbon as formyl-CoA and produce a branched-chain aldehyde, pristanal. Pristanal is then oxidized to pristanic acid (2,6,10,14-tetramethyl pentadecanoic acid), which can be degraded by the peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway for branched-chain carboxylic acids (see below). The CoA thioesters of long-chain 2-hydroxy FA are also shortened by one carbon by enzymes of the α-oxidation pathway [22]. Like the situation with VLCFA, it has not been unequivocally resolved whether phytanic acid, pristanic acid, or 2-hydroxy FA are activated extra- or intraperoxisomally [19, 23].

2.3 β-Oxidation of branched-chain carboxylic acids

Pristanic acid levels are elevated in several peroxisomal disorders, including D-bifunctional protein deficiency and sterol carrier protein-X deficiency [14]. Pristanic acid must be activated to pristanoyl-CoA prior to further catabolism in the peroxisome. Because the first methyl branch is now on the 2-carbon, this FA can be degraded by β-oxidation. Although the reactions are similar to those involved in the degradation of VLCFA, the enzymes of branched-chain FA β-oxidation are somewhat different. Branched-chain acyl-CoA oxidase and sterol carrier protein-X thiolase catalyze the first and fourth enzymatic steps, respectively, while D-bifunctional protein facilitates the second and third reactions. Because of the 2-methyl group, a three carbon compound, propionyl-CoA, is released. Concomitantly, a shortened branched-chain acyl-CoA, 4,8,12-trimethyltridecanoyl-CoA, is produced, which undergoes further rounds of β-oxidation (Fig. 3). Similar to pristanic acid, the side chains of bile acid precursors di- and trihydroxycholestanoic acids must be activated to their CoA derivatives before chain shortening by three carbons via the same peroxisomal β-oxidation pathway (Fig. 3). Not surprisingly, elevated levels of bile acid precursors are found in the same disorders in which pristanic acid accumulates [14].

R- and S- stereoisomers of branched-chain compounds such as phytanic acid, pristanic acid, and bile acid precursors exist in nature due to the presence of asymmetric carbon centers. While the phytanic acid α-oxidation pathway is not stereospecific, yielding both (2S,6R,10R)- and (2R,6R,10R)-isomers of pristanic acid, the branched-chain β-oxidation pathway is stereospecific, only degrading substrates in the S-conformation [24]. Similarly, the bile acid precursors di- and tri-hydroxycholestanoic acids exist as 25R- and 25S-stereoisomers. Peroxisomal α-methyl-acyl-CoA racemase (AMACR) interconverts the CoA derivatives of R- and S-enantiomers, thus functioning as an auxiliary β-oxidation enzyme.

2.4 Plasmalogen synthesis

Ether phospholipid, or plasmalogen, synthesis is impaired in rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata and disorders of peroxisome biogenesis. Several steps in plasmalogen synthesis require activated FAs (Fig. 3). The first step unique to this pathway is catalyzed by peroxisomal glyceronephosphate acyltransferase; in this reaction an intraperoxisomal fatty acyl-CoA is esterified to the sn1 position of dihydroxyacetone phosphate [25]. In the next biosynthetic step, the peroxisomal enzyme alkylglycerone phosphate synthase catalyzes the replacement of the fatty acyl group at sn1 with a 16- or 18-carbon fatty alcohol. Fatty alcohols are produced by fatty acyl-CoA reductases located on the cytoplasmic face of the peroxisome membrane [26]; as the enzyme name indicates, this process requires an activated FA substrate.

3. Peroxisomal ACSs

Historically, the identification of peroxisome-specific ACS activity was hampered by several factors. Until the importance of mammalian peroxisomes in lipid metabolism was recognized in the 1980s, most scientists investigating ACSs focused their attention on mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (microsomes). Inspection of many of the early methods used to isolate mitochondria and microsomes suggests that preparations were likely contaminated with peroxisomes. Even when peroxisomal lipid metabolism began to receive recognition in the scientific literature, procedures for isolation of relatively pure peroxisomes were slow to develop. Despite studies suggesting the existence of very long-chain ACS activity in 1971 [5], it was not until 1985 – shortly after peroxisomal VLCFA β-oxidation was discovered – that an enzyme with very long-chain chain ACS (lignoceroyl-CoA ligase) activity was first reported in the literature [27, 28]. Furthermore, much pioneering work on ACS activity associated with peroxisomes was carried out using methods of classical biochemistry, prior to the “molecular biology/cloning” and “genomic” eras.

The amino acid sequences of many, but not all, peroxisomal proteins contain either of two peroxisome targeting signals, PTS1 or PTS2 [29]. Unfortunately, few ACSs contain a bona fide or even a potential PTS1 and, to the best of our knowledge, none contain a PTS2. Thus, our ability to predict in advance which ACSs are peroxisomal is limited.

3.1 Yeasts and fungi

One of the earliest references to a peroxisomal ACS is from Mishina et al., who reported that one of the two fatty acid activating enzymes in the yeast Candida lipolytica was found in mitochondria and microsomes, whereas the other enzyme localized to “microbodies”, or peroxisomes [30]. The existence of a peroxisomal ACS was a significant finding, as FA β-oxidation occurs solely in this organelle in yeast. Gordon and coworkers identified 4 long-chain ACS genes (FAA1-4) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but reported that none of them was exclusively responsible for targeting exogenous FAs to peroxisomes for β-oxidation [31]; importantly, they also found that yeast could still grow using FAs as sole carbon source even after deletion of all four FAA genes, suggesting the existence of at least one additional ACS in this organism. Gene deletion studies suggest that Faa1p and/or Faa4p provide activated FA for peroxisomal β-oxidation [32], but specific localization studies were not carried out. Although initially thought to be a long-chain ACS, Faa2p was subsequently determined to be an intraperoxisomal medium-chain ACS that localizes to the inner leaf of the peroxisomal membrane [33–35]. It is thought that medium-chain FAs enter yeast peroxisomes by diffusion (flip-flop) and are then activated in the organelle matrix. This is similar to the process by which medium-chain FAs enter mammalian mitochondria, which does not require the regulated carnitine-dependent mechanism used for transport of long-chain acyl-CoAs into the mitochondrial matrix. It is also possible that medium-chain FAs can enter peroxisomes via the pore-forming protein, Pxmp2, or its homologs [36].

Kalish et al. found very long-chain ACS activity associated with peroxisomes in the yeast Pichia pastoris [37]. Subsequently, the orthologous enzyme was identified in S. cerevisiae and determined to be the product of the FAT1 gene [38, 39]. Studies of gene deletion mutants revealed that the ACS activity of Fat1p was associated with microsomes as well as peroxisomes. Mechanistic studies by Black, DiRusso, and colleagues demonstrated that Fat1p and Faa1p (and to a lesser extent Faa4p) constitute a tightly regulated system for the import, activation, and peroxisomal β-oxidation of long- and very long-chain FAs [40, 41]. S. cerevisiae also contains a gene, FAT2, encoding a protein predicted to be a peroxisomal ACS [9, 42]. Fat2p contains the two highly conserved motifs characteristic of all ACSs (Fig. 2) [6], as well as the cannonical peroxisome targeting signal 1 (PTS1), the tripeptide – SKL, at its carboxy terminus. However, the substrate specificity and metabolic function of Fat2p remain unknown.

Peroxisomal ACSs have also been found in some fungi. A survey of the Aspergillus nidulans genome identified six likely ACSs, one of which was peroxisomal [43]. This enzyme, FaaB, was found to be the major ACS for degradation of long-chain FAs. FaaB was required for growth of A. nidulans on FAs as carbon source, and its gene was induced when this fungus was grown in the presence of FAs. The two final reactions in the synthesis of penicillin by Penicillium chrysogenum are also peroxisomal [44, 45]. The ACS phenylacetyl-CoA ligase supplies the activated substrate for acyl-CoA:6-amino penicillanic acid acyltransferase; the product of the latter reaction is penicillin G.

3.2 Plants

Plants require ACS activity for the formation of phospholipids, triacylglycerol, jasmonate, and for the oxidation of fatty acids. In 2002, nine long-chain ACSs were identified in Arabidopsis thaliana [46]. Two of these long-chain ACSs, LACS6 and LACS7, were shown to be located in the peroxisome, where a majority of β-oxidation takes place during plant seedling development [47]. The knockout of either A. thaliana peroxisomal ACS alone did not robustly alter plant viability; however, the knockout of both peroxisomal ACSs caused defective seed lipid mobilization [48]. The identification of plant LACS at the interface between lipid bodies and peroxisomes suggested that lipids are mobilized from lipid bodies, activated by peroxisomal ACSs, and then degraded by β-oxidation [49]. Thus, plant peroxisomal ACS activity, and subsequent β-oxidation, is required for normal seed germination.

Jasmonic acid is potent plant signaling molecule that plays roles in regulating plant defense mechanisms, metabolism, and development. Jasmonate is synthesized from linolenic acid (C18:3ω3) through a process that occurs in three cellular compartments: plastids, peroxisomes, and cytosol. In 2005 and 2006, several 4-coumarate:CoA ligase-like Arabidopsis peroxisomal proteins were found to have ACS activity towards jasmonate precursors as well as long-chain FAs [50–52]. These data suggest that formation of jasmonic acid requires the ligase activity provided by peroxisomal ACS enzymes; however the specific ACS required for this activity has not been identified.

3.3 Invertebrate ACSs

Firefly luciferase is a peroxisomal enzyme whose two-step reaction mechanism resembles that of ACSs (illustrated in the Introduction). In the first ATP-requiring step, the substrate, luciferin, is adenylated with the release of PPi. The second step is the oxygen-dependent conversion of the adenylated substrate to oxyluciferin with release of AMP and the production of light. Oba and colleagues demonstrated that luciferases from the North American firefly (Photinus pyralis) and the Japanese firefly (Luciola cruciata) also had long-chain ACS activity, suggesting that they were bifunctional enzymes [53]. In D. melanogaster, the firefly luciferase ortholog, CG6178, has ACS activity but not luciferase activity [54]. An expansive, but not comprehensive, phylogenic analysis of the acyl-CoA synthetases across species suggests that CG6178 forms a clade with unknown fungi ACS genes and plant 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), and these genes are phylogenetically distinct from ACSL genes in mammals and yeast [54]. Of the ACS genes phylogenetically analyzed, the luciferases, plant 4CLs, several fungi ACSs, and CG6178 contain a PTS1, whereas none of the vertebrate ACSL genes contain this targeting motif, suggesting that the peroxisomal specific nature of these ACSs has been lost in the vertebrate lineage. D. melanogaster also expresses a homolog of human ACSL4, dAcsl, early in embryonic development [55]. Mutations in dAcsl cause defects in embryonic segmentation, although the mechanism by which dAcsl affects this process remains unclear. In C. elegans, the ACSL homolog Y65B4BL.5 and the ACSVL homolog F28D1.9 do not lead to growth defects when knocked down using RNA interference [56]. Thus, specific ACSL isoform activities appear to be critical for fly development, but are not for worm development. Furthermore, the PTS1 found in invertebrate ACSs are not conserved in vertebrates suggesting distinct evolutionary differences in the roles of ACSL enzymes.

3.4 Mammals: long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSL)

Activation of palmitic acid (C16:0) in peroxisome-enriched fractions of rat liver was reported by Shindo and Hashimoto at about the same time as the discovery of ACS in Candida peroxisomes [57]. This finding was soon confirmed in purified peroxisomes by other laboratories [58, 59]. ACS activity remained associated with peroxisomal membranes when organelles were disrupted, indicating that it was not a matrix enzyme [59]. Most of this palmitoyl-CoA synthetase activity was destroyed when intact peroxisomes were treated with the proteinase Pronase, suggesting that it was topographically orientated facing the cytoplasm [59]. Measurement of ACS activity in liver subcellular fractions showed that approximately 16% of liver long-chain ACS activity occurs in peroxisomes [60]. Peroxisomal long-chain ACSs are also thought to catalyze the activation of the branched-chain FAs phytanate and pristanate [23, 61–63].

3.4.1 Which ACSL isoform is peroxisomal?

None of the five mammalian ACSL isoforms contain either PTS1 or PTS2. To determine which ACSL isoform is expressed in the peroxisome, Lewin et al. examined protein abundance of ACSL1, ACSL4, and ACSL5 in liver subcellular fractions using isoform specific antibodies [64]. Peroxisomal fractions were identified by high peroxisomal-specific catalase activity. These peroxisomal fractions were clear of microsomal and mitochondrial contamination as evidenced by the lack of esterase and glutamate dehydrogenase activity. ACSL4 was highly abundant in the peroxisomal fraction. This protein was also detected in the mitochondria-associated membrane fraction, but its abundance was nearly 10-fold higher in the peroxisomal fraction. Troglitazone, an inhibitor of ACSL4 but not of the other ACSL isoforms [65, 66], decreased total ACSL activity by ~30% in the peroxisomal rich fractions, suggesting that other ACS enzymes (likely very long-chain ACSs) contribute up to 70% of the remaining ACS activity. These data suggest that ACSL4 is highly expressed in liver peroxisomes.

Purified peroxisomal fractions have been analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify the peroxisomal proteome. In 2003, proteomic analysis of rat liver peroxisomes, isolated by subcellular fractionation followed by immunoprecipitation of organelles using an antibody to the 70-kDa peroxisomal membrane protein (ABCD3), identified “long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 2” (now called ACSL1) as a peroxisomal membrane protein [67]. This was confirmed In a 2006 proteomic analysis of rat liver peroxisomal membrane fractions isolated by fractionation followed by incubation at high pH to release inner peroxisomal proteins [68]. Islinger et al. investigated the hepatic peroxisomal proteome of rats treated with the peroxisome proliferator, clofibrate, and also identified ACSL1 as a peroxisomal protein [69]. In 2010, proteomic analysis of rat liver heavy peroxisome fraction was compared to light peroxisomal fraction isolated by fractionation [70]. These authors identified ACSL1 in the mitochondria, peroxisome, and the ER while ACSL5 was found in the ER. The lack of identification of ACSL4 and ACSL3 in any of the fractions, suggests that either common fractionation methods lead to loss of substantial proteins or that the mass spectrometry methods employed do not allow for complete identification of all ACSL proteins. Overall the proteomic approach strongly suggests that ACSL1 is a peroxisomal protein in the liver.

An inherent problem with fractionation methods is the contamination of peroxisomal fractions with ER proteins; thus it is difficult to conclusively determine whether a protein identified by proteomics from a peroxisomal fraction is truly peroxisomal and not ER contamination. Furthermore, because ACSL4 is a membrane-associated protein but not a transmembrane protein, and because it was not identified in any cell fraction from any of the above mentioned studies, it is possible that ACSL4 is removed from the fraction by the methods used. Despite the identification of ACSL1 in the peroxisome by proteomics, there are no studies that identify ACSL1 as a peroxisomal protein using non-proteomic approaches, nor are there reports that elude to ACSL1 playing a functional role in the peroxisome.

3.4.2 ACSL4 effects on metabolism

Because ACSL4 is the only ACSL isoform to be identified at the peroxisome using specific antibodies, it is likely that ACSL4 serves a specialized role at the peroxisome. Recombinant ACSL4 has a high preference for long-chain polyunsaturated FAs, mainly arachidonic acid (C20:4ω6) (AA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5ω3). The high abundance of ACSL4 in steroidogenic tissues and its preference for AA and eicosapentaenoic acid, the precursors for prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis, suggests that ACSL4 plays a role in regulating the availability of these fatty acids for the synthesis of eicosanoids [71].. Because eicosanoid synthesis begins with a free fatty acid, not an acyl-CoA, ACSL4 activity would be predicted to reduce the flux of fatty acids towards eicosanoid synthesis. Indeed the overexpression of ACSL4 in human smooth muscle cells leads to reduced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secretion [72]. Likewise, the inhibition of ACSL4 with rosiglitazone or triacsin C increased PGE2 release from smooth muscle cells [72]. These data suggest that ACSL4 plays a role in regulating prostaglandin synthesis. While inhibition of ACSL4 with thiazolidinediones increases eicosanoid synthesis in smooth muscle cells, the knockdown of ACSL4 in Leydig cells of the testis decreases progesterone synthesis [73]. Similarly, the knockdown of ACSL4 in cancer cells decreases the production of 5-, 12-, and 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and PGE2 [74]. The high expression of ACSL4 seen in some cancers is linked to increased invasiveness. Thus, the increased invasiveness of tumors that highly express ACSL4 is potentially mediated by increased steroid and eicosanoid production [75]. Alternatively, the increased ACSL4 expression may be a mechanism of cancer cells to decrease apoptosis that is triggered by free arachidonate levels [76]. Whether ACSL4s activity on AA occurs at the peroxisome or the mitochondria-associated membrane has not been investigated, thus any potential link between peroxisomal ACSL4 and prostaglandin synthesis remains unclear. Very little research has been conducted to determine the peroxisomal specific ACSL isoform and the function of ACSLs at the peroxisome. We conclude that further investigation into the role of ACSL at the peroxisome is warranted.

3.5 Mammals: very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSVL)

The discovery that peroxisomal β-oxidation of VLCFA was impaired in peroxisome biogenesis disorders and in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy prompted several laboratories to search for a peroxisomal ACS that could activate VLCFA substrates. Using methods of classical biochemistry, Hashimoto and colleagues succeeded in purifying such an enzyme from rat liver peroxisomes in 1996 [77]. These investigators then used genetic methods to clone cDNA encoding the protein [78]. The amino acid sequence of this enzyme, which our laboratory subsequently designated ACSVL1 because it was the first bona fide very long-chain ACS reported [79], was similar to, but distinct from, that of ACSL isoforms known at that time. The sequence was, however, more similar to that of “fatty acid transport protein” (now FATP1, or SLC27A1) (see Table 1) [80]. ACSVL1 (FATP2; SLC27A2) is found in both peroxisomes and microsomes [19, 78]. The C-terminus of the human, rat, and mouse protein ends in the tripeptide – LKL; although this is not a recognized variant of PTS1, its similarity to the consensus sequence – SKL suggests that it may be partially functional. ACSVL1 is primarily expressed in liver and kidney, with little expression in brain [19]. In peroxisomes, the role of this enzyme is presumed to be the activation of VLCFA for β-oxidation. Studies done using skin fibroblasts from patients with peroxisome biogenesis disorders and X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy suggested that for VLCFA to be β-oxidized in peroxisomes, activation had to occur in peroxisomes, not microsomes. Although its abundance in microsomes is significantly higher than in peroxisomes, ACSVL1’s function in the endoplasmic reticulum is not known.

Overexpression of ACSVL1 in COS-1 cells suggests that this enzyme can activate long-chain FAs (e.g. palmitic acid; C16:0), VLCFAs (e.g. lignoceric acid; C24:0), and branched-chain FAs phytanic acid and pristanic acid [19]. The topographic orientation of ACSVL1 in the peroxisomal membrane has not completely been resolved [15–19]. Investigations into the function of the peroxisomal membrane protein ABCD1, which is defective in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy, suggests that VLCFA are activated extraperoxisomally via ACSVL1 (or another ACS) oriented facing the cytoplasm, after which the CoA derivatives are transported into the organelle by ABCD1 [81]. On the other hand, orientation of the enzyme facing the matrix is appealing with respect to branched-chain FA metabolism. When phytanic acid is degraded by the peroxisomal α-oxidation pathway, the product, pristanal, is then oxidized to pristanic acid. If the ACSVL1 active site faces the peroxisomal matrix, pristanic acid could then be activated intraperoxisomally to its CoA derivative and then further degradation via peroxisomal β-oxidation in a metabolically efficient manner (Fig. 3). Whether phytanic acid is activated primarily by ACSVL1, or by another ACS (e.g. ACSL1 or ACSL4) oriented in the peroxisomal membrane facing the cytoplasm [23, 61], remains unresolved.

The bile acid precursor, trihydroxycholestanoic acid, was also a substrate for ACSVL1 when the enzyme was expressed in COS-1 cells [82]. Trihydroxycholestanoyl-CoA undergoes one cycle of peroxisomal β-oxidation, yielding the CoA derivative of the primary bile acid, cholate (Fig. 3). Intraperoxisomal choloyl-CoA then reacts with glycine or taurine to form the conjugated bile acids glycocholate and taurocholate, respectively [83]. However, it is unclear whether it is the peroxisomal ACSVL1 or the microsomal ACSVL1 that activates bile acid precursors.

An ACSVL1 knockout mouse was generated by Heinzer et al. [84]. Although this mouse had no obvious phenotypic abnormalities, the rate of hepatic and renal VLCFA β-oxidation was reduced. Despite decreased VLCFA degradation in these tissues, plasma levels of VLCFA were not elevated in the ACSVL1 knockout mouse.

There is evidence that another member of the ACSVL family, FATP4 (SLC27A4; suggested name ACSVL5 [85]), partially localizes to peroxisomes. FATP4 localized to the endoplasmic reticulum when heterologously expressed in several cell lines, including HeLa and COS [86]. While the endogenous enzyme was found in endoplasmic reticulum, it was detected in peroxisomes, mitochondria, and mitochondria-associated membranes as well [87]. The C-terminus of human, rat, and mouse FATP4 ends in the tripeptide – EKL. Like the situation with ACSVL1, this sequence is not recognized as a PTS1 variant but may be partially functional. FATP4 was found to be the primary VLCFA-activating enzyme in skin fibroblasts and, unlike ACSVL1, was also found in brain, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, heart, and intestine [87]. Fibroblasts grown from the skin of FATP4-null mice had a >50% reduction in the rate of VLCFA β-oxidation, suggesting that FATP4 may be the primary ACSVL in tissues not expressing ACSVL1. In HeLa cells heterologously expressing FATP4, the protein was oriented in the endoplasmic reticulum with its N-terminus toward the lumen [86]; the topographic orientation of endogenous FATP4 in peroxisomes or other organelles has not been studied. A role for this enzyme in peroxisomal metabolic processes other than VLCFA β-oxidation has not been evaluated.

4. Peroxisomal ACSs and human disease

Although ACSs are clearly indispensible for several peroxisomal metabolic pathways, there have been no direct correlations between peroxisomal deficiency of a specific ACS and human disease. In the mid to late 1980s, it was hypothesized that deficiency of “the peroxisomal very long-chain ACS” was the biochemical defect in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy [88–92]. This was proven incorrect when the defective gene in this disease, ABCD1, was identified in 1993 by positional cloning [93]. Nonetheless, results of yeast two-hybrid and surface plasmon resonance experiments suggest that ABCD1 and ACSVL1 physically interact in peroxisomes [94]. Studies by Yamada et al. with ABCD1-deficient mice also indicated that ABCD1 was required for proper localization and functioning of ACSVL1 [95, 96]. However, Smith and colleagues separately produced ABCD1 knockout mice and reported no effects on either expression or localization of ACSVL1 [84].

Deficiency of FATP4 causes a restrictive dermopathy in mice [97, 98]. Because the lungs cannot expand normally, newborn pups rarely survive for more than a day. Mutations in FATP4 have been found in humans with the autosomal recessive disorder, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome [99]. Individuals with this disease are born prematurely and have neonatal asphyxia. Throughout life, they have nonscaly ichthyosis with atopic manifestations. Decreased very long-chain ACS activity and reduced incorporation of VLCFA into cellular lipids was observed in skin fibroblasts from a patient with ichthyosis prematurity syndrome [99]. Because this enzyme is found in multiple cellular compartments, it is unclear if either peroxisomal FATP4, or metabolism of FATP4-derived VLCFA-CoA in peroxisomes, contributes to the clinical manifestations of this disease.

Several laboratories have reported changes in peroxisomal ACSs that have potential relevance to diabetes and/or insulin resistance. Singh and coworkers measured ACS activity in peroxisomes and mitochondria isolated from livers of diabetic rats. They found that in peroxisomes, activation of the long-chain FA palmitate was increased 2.6-fold, while in mitochondria there was a 2.1-fold increase; peroxisomal VLCFA-CoA synthesis measured with lignoceric acid was increased 2.6-fold [100]. Durgan et al. studied the transcriptional regulation of ACSL isoforms in mouse heart and found that neither diabetes experimentally induced with Streptozotocin nor a high-fat diet induced expression of ACSL4 [101]. However, in humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver and insulin resistance, hepatic ACSL4 mRNA was significantly increased [102]. In a study of 600 Swedish men, a single nucleotide polymorphism in ACSL4 (rs7887981) was associated with statistically significant elevations in fasting serum insulin and triglyceride concentrations [103]. It was mentioned previously that thiazolidinedione insulin-sensitizing drugs such as troglitazone, rosiglitazone, and pioglitazone used in the treatment of diabetes specifically inhibited ACSL4 activity [66, 104]. Thiazolidinediones are also PPARγ ligands, but the effects of these drugs on ACSL4 may be independent of PPARγ [66]. Whether or not inhibition of ACSL4 is responsible for the anti-diabetic properties of thiazolidinediones will require further investigation.

Hepatic steatosis is a complication of estrogen deficiency in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients; this has been studied in a mouse model in which the gene encoding aromatase, an essential enzyme of estrogen biosynthesis, has been knocked out [105]. In this mouse, ACSVL1 mRNA was decreased, along with peroxisomal VLCFA β-oxidation activity [105]. Treatment of aromatase-deficient mice with either the PPARα agonist, bezafibrate, or a novel statin, pitavastatin, restored ACSVL1 mRNA levels along with mRNA for several enzymes of peroxisomal β-oxidation [106, 107].

5. Peroxisome proliferators, xenobiotics, and peroxisomal ACSs

Many xenobiotic compounds containing an aliphatic carboxylic acid function can serve as substrates for ACSs located in peroxisomes and other subcellular compartments. Once activated, these compounds can be incorporated into complex lipids and/or be degraded. Some of these compounds (e.g. clofibrate, nafenopin, and related fibric acid derivatives) have also been identified as peroxisome proliferators in rodents and function as ligands for PPARs, primarily PPARα. Other xenobiotics thought to be activated by peroxisomal long-chain ACS include 2-arylpropionates (e.g. ibuprofen, naproxen, and related non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and herbicides (e.g. silvex and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetate). These topics have been comprehensively reviewed by Knights [12].

PPARα activation by xenobiotics (or perhaps their CoA derivatives) induces the expression of peroxisomal long-chain ACS activity. Lewin et al. reported a 40% increase in ACSL4 mRNA abundance in livers of rats treated with the synthetic PPARα agonist GW9578 [64]. Peroxisomal very long-chain ACS activity was induced 4-fold in rats treated with the PPARα ligand ciprofibrate [108].

Peroxisomal β-oxidation is thought to be an important route for degradation of some xenobiotics, such as ω-phenyl FAs; Yamada and coworkers found that peroxisomal β-oxidation of a 12-carbon ω-phenyl FA required activation by an ACS found in peroxisomes [109]. The CoA thioester of the anti-epileptic drug valproic acid was reported to be metabolized by β-oxidation in peroxisomes, suggesting the participation of a peroxisomal ACS [110]; however, more recent work suggests that valproate is also degraded in mitochondria [111].

Xenobiotics are not exclusively activated by peroxisomal ACSs, however. Sulfur- and sulfoxy-substituted FA analogues (e.g. tetradecylthioacetic acid) [112], oxa-FAs (e.g. 3,6,9-trioxadecanoic acid) [113], ciprofibrate [114], and fenoprofen [115] were activated by ACSs in mitochondria and/or microsomes as well as in peroxisomes.

6. Concluding remarks

It has firmly been established that several peroxisomal metabolic pathways require the participation of one or more ACSs. These include the β-oxidation of VLCFA, the α- and β-oxidation of branched chain FAs and the synthesis of plasmalogens. Most, if not all, of the ACSs present in the genomes of humans, mice, and many other species have been identified. Despite this progress over many decades of research, rigorous assignment of a specific ACS to a specific pathway has not yet been achieved. The activation and oxidation of branched-chain FA, VLCFA, and xenobiotics at the peroxisome suggest an important role for peroxisomal ACSs in cellular metabolism. The existence of multiple ACS enzymes associated with peroxisomes suggests that each isoform has a specific function in peroxisomal metabolism. Alternatively, peroxisomal ACSs may have overlapping responsibilities because these enzymes play critical roles in cellular metabolism. Clarification of these complex issues will require further investigation.

Highlights.

Peroxisomes carry out several metabolic processes requiring activated fatty acids (acyl-CoAs)

Acyl-CoA synthetases catalyze the formation of activated fatty acids

Peroxisomes have acyl-CoA synthetase activity, but only three of the 26 mammalian enzymes have been detected in peroxisomes

This article summarizes the current state of knowledge of peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetase function

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants NS062043 (PAW), HD024061 (PAW), and DK007751 (JME).

Abbreviations

- AA

Arachidonic acid (C204ω6)

- ACS

Acyl-CoA synthetase

- CoA

Coenzyme A

- FA

Fatty acid

- FATP

Fatty acid transport protein

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- VLCFA

Very long-chain fatty acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Paul A. Watkins, Hugo W. Moser Research Institute at Kennedy Krieger, and Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Jessica M. Ellis, Department of Biological Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

References

- 1.Gangar A, Karande AA, Rajasekharan R. Purification and characterization of acyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase from oleaginous yeast and its role in triacylglycerol biosynthesis. Biochem J. 2001;360:471–479. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang Y, Morgan-Kiss RM, Campbell JW, Chan CH, Cronan JE. Expression of Vibrio harveyi acyl-ACP synthetase allows efficient entry of exogenous fatty acids into the Escherichia coli fatty acid and lipid A synthetic pathways. Biochemistry. 49:718–726. doi: 10.1021/bi901890a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo AJ, Fulda M, Browse J, Ohlrogge JB. Identification of a plastid acyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase in Arabidopsis and its role in the activation and elongation of exogenous fatty acids. Plant J. 2005;44:620–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu S, Ohkuma S. Inorganic pyrophosphatase of clofibrate-induced rat liver peroxisomes. J Biochem. 1993;113:462–466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aas M. Organ and subcellular distribution of fatty acid activating enzymes in the rat. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;231:32–47. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(71)90253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins PA, Maiguel D, Jia Z, Pevsner J. Evidence for 26 distinct acyl-coenzyme A synthetase genes in the human genome. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2736–2750. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700378-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shockey J, Browse J. Genome-level and biochemical diversity of the acyl-activating enzyme superfamily in plants. Plant J. 2011;66:143–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black PN, Zhang Q, Weimar JD, DiRusso CC. Mutational analysis of a fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase signature motif identifies seven amino acid residues that modulate fatty acid substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4896–4903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberg SJ, Morgenthaler J, Heinzer AK, Smith KD, Watkins PA. Very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. Human “bubblegum” represents a new family of proteins capable of activating very long-chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35162–35169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mashek DG, Bornfeldt KE, Coleman RA, Berger J, Bernlohr DA, Black P, DiRusso CC, Farber SA, Guo W, Hashimoto N, Khodiyar V, Kuypers FA, Maltais LJ, Nebert DW, Renieri A, Schaffer JE, Stahl A, Watkins PA, Vasiliou V, Yamamoto TT. Revised nomenclature for the long chain mammalian acyl-CoA synthetase gene family. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1958–1961. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferdinandusse S, Denis S, Faust PL, Wanders RJ. Bile acids: the role of peroxisomes. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2139–2147. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900009-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knights KM. Role of hepatic fatty acid:coenzyme A ligases in the metabolism of xenobiotic carboxylic acids. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:776–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knights KM, Drogemuller CJ. Xenobiotic-CoA ligases: kinetic and molecular characterization. Curr Drug Metab. 2000;1:49–66. doi: 10.2174/1389200003339261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wanders RJ, Ferdinandusse S, Brites P, Kemp S. Peroxisomes, lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lageweg W, Tager JM, Wanders RJ. Topography of very-long-chain-fatty-acid-activating activity in peroxisomes from rat liver. Biochem J. 1991;276(Pt 1):53–56. doi: 10.1042/bj2760053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazo O, Contreras M, Singh I. Topographical localization of peroxisomal acyl-CoA ligases: differential localization of palmitoyl-CoA and lignoceroyl-CoA ligases. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3981–3986. doi: 10.1021/bi00468a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith BT, Sengupta TK, Singh I. Intraperoxisomal Localization of Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acyl-CoA Synthetase: Implication in X-Adrenoleukodystrophy. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254:309–320. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg SJ, Kemp S, Braiterman LT, Watkins PA. Role of very-long-chain acyl-coenzyme A synthetase in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:409–412. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<409::aid-ana18>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinberg SJ, Wang SJ, Kim DG, Mihalik SJ, Watkins PA. Human very-long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase: cloning, topography, and relevance to branched-chain fatty acid metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:615–621. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanders RJ, Komen J, Ferdinandusse S. Phytanic acid metabolism in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wanders RJ. Metabolic and molecular basis of peroxisomal disorders: a review. Am J Med Genet. 2004;126A:355–375. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foulon V, Sniekers M, Huysmans E, Asselberghs S, Mahieu V, Mannaerts GP, Van Veldhoven PP, Casteels M. Breakdown of 2-hydroxylated straight chain fatty acids via peroxisomal 2-hydroxyphytanoyl-CoA lyase: a revised pathway for the alpha-oxidation of straight chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9802–9812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pahan K, Singh I. Phytanic acid oxidation: Topographical localization of phytanoyl-CoA ligase and transport of phytanic acid into human peroxisomes. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:986–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferdinandusse S, Rusch H, van Lint AE, Dacremont G, Wanders RJ, Vreken P. Stereochemistry of the peroxisomal branched-chain fatty acid alpha- and beta-oxidation systems in patients suffering from different peroxisomal disorders. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. Biochemistry of mammalian peroxisomes revisited. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:295–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng JB, Russell DW. Mammalian Wax Biosynthesis: I. IDENTIFICATION OF TWO FATTY ACYL-COENZYME A REDUCTASES WITH DIFFERENT SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITIES AND TISSUE DISTRIBUTIONS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37789–37797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406225200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh I, Singh R, Bhushan A, Singh AK. Lignoceroyl-CoA ligase activity in rat brain microsomal fraction: topographical localization and effect of detergents and alpha-cyclodextrin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;236:418–426. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagamatsu K, Soeda S, Mori M, Kishimoto Y. Lignoceroyl-coenzyme A synthetase from developing rat brain: partial purification, characterization and comparison with palmitoyl-coenzyme A synthetase activity and liver enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;836:80–88. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanyon-Hogg T, Warriner SL, Baker A. Getting a camel through the eye of a needle: the import of folded proteins by peroxisomes. Biol Cell. 102:245–263. doi: 10.1042/BC20090159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mishina M, Kamiryo T, Tashiro S, Hagihara T, Tanaka A, Fukui S, Osumi M, Numa S. Subcellular localization of two long-chain acyl-coenzyme A synthetases in Candida lipolytica. Eur J Biochem. 1978;89:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson DR, Knoll LJ, Levin DE, Gordon JI. Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains four fatty acid activation (FAA) genes: An assessment of their role in regulating protein N-myristoylation and cellular lipid metabolism. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:751–762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faergeman NJ, Black PN, Zhao XD, Knudsen J, DiRusso CC. The Acyl-CoA synthetases encoded within FAA1 and FAA4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function as components of the fatty acid transport system linking import, activation, and intracellular Utilization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37051–37059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hettema EH, van Roermund CW, Distel B, van den Berg M, Vilela C, Rodrigues-Pousada C, Wanders RJ, Tabak HF. The ABC transporter proteins Pat1 and Pat2 are required for import of long-chain fatty acids into peroxisomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1996;15:3813–3822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Roermund CW, Tabak HF, van Den Berg M, Wanders RJ, Hettema EH. Pex11p plays a primary role in medium-chain fatty acid oxidation, a process that affects peroxisome number and size in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:489–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verleur N, Hettema EH, van Roermund CW, Tabak HF, Wanders RJ. Transport of activated fatty acids by the peroxisomal ATP-binding- cassette transporter Pxa2 in a semi-intact yeast cell system. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:657–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rokka A, Antonenkov VD, Soininen R, Immonen HL, Pirila PL, Bergmann U, Sormunen RT, Weckstrom M, Benz R, Hiltunen JK. Pxmp2 is a channel-forming protein in Mammalian peroxisomal membrane. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalish JE, Chen CI, Gould SJ, Watkins PA. Peroxisomal activation of long- and very long-chain fatty acids in the yeast Pichia pastoris. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:335–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi JY, Martin CE. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae FAT1 gene encodes an acyl-CoA synthetase that is required for maintenance of very long chain fatty acid levels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4671–4683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watkins PA, Lu JF, Steinberg SJ, Gould SJ, Smith KD, Braiterman LT. Disruption of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae FAT1 gene decreases very long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase activity and elevates intracellular very long-chain fatty acid concentrations. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18210–18219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Black PN, DiRusso CC. Yeast acyl-CoA synthetases at the crossroads of fatty acid metabolism and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zou Z, Tong F, Faergeman NJ, Borsting C, Black PN, DiRusso CC. Vectorial acylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Fat1p and fatty acyl-CoA synthetase are interacting components of a fatty acid import complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16414–16422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blobel F, Erdmann R. Identification of a yeast peroxisomal member of the family of AMP-binding proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:468–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0468h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reiser K, Davis MA, Hynes MJ. Aspergillus nidulans contains six possible fatty acyl-CoA synthetases with FaaB being the major synthetase for fatty acid degradation. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0565-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamas-Maceiras M, Vaca I, Rodriguez E, Casqueiro J, Martin JF. Amplification and disruption of the phenylacetyl-CoA ligase gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding an aryl-capping enzyme that supplies phenylacetic acid to the isopenicillin N acyltransferase. Biochem J. 2005 doi: 10.1042/BJ20051599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meijer WH, Gidijala L, Fekken S, Kiel JA, van den Berg MA, Lascaris R, Bovenberg RA, van der Klei IJ. Peroxisomes are required for efficient penicillin biosynthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5702–5709. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02327-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shockey JM, Fulda MS, Browse JA. Arabidopsis contains nine long-chain acyl-coenzyme a synthetase genes that participate in Fatty Acid and glycerolipid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1710–1722. doi: 10.1104/pp.003269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fulda M, Shockey J, Werber M, Wolter FP, Heinz E. Two long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases from Arabidopsis thaliana involved in peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation. Plant J. 2002;32:93–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulda M, Schnurr J, Abbadi A, Heinz E, Browse J. Peroxisomal Acyl-CoA Synthetase Activity Is Essential for Seedling Development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2004;16:394–405. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayashi Y, Hayashi M, Hayashi H, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M. Direct interaction between glyoxysomes and lipid bodies in cotyledons of the Arabidopsis thaliana ped1 mutant. Protoplasma. 2001;218:83–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01288364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koo AJ, Chung HS, Kobayashi Y, Howe GA. Identification of a peroxisomal acyl-activating enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33511–33520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koo AJ, Howe GA. Role of Peroxisomal beta-Oxidation in the Production of Plant Signaling Compounds. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2:20–22. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.1.3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider K, Kienow L, Schmelzer E, Colby T, Bartsch M, Miersch O, Wasternack C, Kombrink E, Stuible HP. A new type of peroxisomal Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase from arabidopsis thaliana has the catalytic capacity to activate biosynthetic precursors of jasmonic acid. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13962–13972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oba Y, Ojika M, Inouye S. Firefly luciferase is a bifunctional enzyme: ATP-dependent monooxygenase and a long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 2003;540:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oba Y, Sato M, Ojika M, Inouye S. Enzymatic and genetic characterization of firefly luciferase and Drosophila CG6178 as a fatty acyl-CoA synthetase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:819–828. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Gao Y, Zhao X, Wang Z. Drosophila long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase acts like a gap gene in embryonic segmentation. Dev Biol. 353:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petriv OI, Pilgrim DB, Rachubinski RA, Titorenko VI. RNA interference of peroxisome-related genes in C. elegans: a new model for human peroxisomal disorders. Physiol Genomics. 2002;10:79–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00044.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shindo Y, Hashimoto T. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase and fatty acid oxidation in rat liver peroxisomes. J Biochem. 1978;84:1177–1181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berge RK, Osmundsen H, Aarsland A, Farstad M. The existence of separate peroxisomal pools of free coenzyme a and long-chain acyl-CoA in rat liver, demonstrated by a specific high performance liquid chromatography method. Int J Biochem. 1983;15:205–209. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(83)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mannaerts GP, Van Veldhoven PVBA, Vandebroek G, Debeer LJ. Evidence that peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetase is located at the cytoplasmic side of the peroxisomal membrane. Biochem J. 1982;204:17–23. doi: 10.1042/bj2040017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bronfman M, Inestrosa NC, Nervi FO, Leighton F. Acyl-CoA synthetase and the peroxisomal enzymes of beta-oxidation in human liver. Quantitative analysis of their subcellular localization. Biochem J. 1984;224:709–720. doi: 10.1042/bj2240709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh H, Brogan M, Johnson D, Poulos A. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation of branched chain fatty acids in human skin fibroblasts. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1597–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wanders RJ, Denis S, van Roermund CW, Jakobs C, ten Brink HJ. Characteristics and subcellular localization of pristanoyl-CoA synthetase in rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1125:274–279. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watkins PA, Howard AE, Gould SJ, Avigan J, Mihalik SJ. Phytanic acid activation in rat liver peroxisomes is catalyzed by long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:2288–2295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewin TM, Van Horn CG, Krisans SK, Coleman RA. Rat liver acyl-CoA synthetase 4 is a peripheral-membrane protein located in two distinct subcellular organelles, peroxisomes, and mitochondrial-associated membrane. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;404:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Horn CG, Caviglia JM, Li LO, Wang S, Granger DA, Coleman RA. Characterization of Recombinant Long-Chain Rat Acyl-CoA Synthetase Isoforms 3 and 6: Identification of a Novel Variant of Isoform 6. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1635–1642. doi: 10.1021/bi047721l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim JH, Lewin TM, Coleman RA. Expression and characterization of recombinant rat Acyl-CoA synthetases 1, 4, and 5. Selective inhibition by triacsin C and thiazolidinediones. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24667–24673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kikuchi M, Hatano N, Yokota S, Shimozawa N, Imanaka T, Taniguchi H. Proteomic analysis of rat liver peroxisome: presence of peroxisome-specific isozyme of Lon protease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:421–428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Islinger M, Luers GH, Zischka H, Ueffing M, Volkl A. Insights into the membrane proteome of rat liver peroxisomes: Microsomal glutathione-S-transferase is shared by both subcellular compartments. Proteomics. 2005 doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Islinger M, Luers GH, Li KW, Loos M, Volkl A. Rat liver peroxisomes after fibrate treatment. A survey using quantitative mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23055–23069. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Islinger M, Li KW, Loos M, Liebler S, Angermuller S, Eckerskorn C, Weber G, Abdolzade A, Volkl A. Peroxisomes from the heavy mitochondrial fraction: isolation by zonal free flow electrophoresis and quantitative mass spectrometrical characterization. J Proteome Res. 9:113–124. doi: 10.1021/pr9004663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang MJ, Fujino T, Sasano H, Minekura H, Yabuki N, Nagura H, Iijima H, Yamamoto TT. A novel arachidonate-preferring acyl-coa synthetase is present in steroidogenic cells of the rat adrenal, ovary, and testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2880–2884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Golej DL, Askari B, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Pennathur S, Bornfeldt KE. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 modulates prostaglandin E release from human arterial smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:782–793. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M013292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cornejo Maciel F, Maloberti P, Neuman I, Cano F, Castilla R, Castillo F, Paz C, Podesta EJ. An arachidonic acid-preferring acyl-CoA synthetase is a hormone-dependent and obligatory protein in the signal transduction pathway of steroidogenic hormones. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;34:655–666. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maloberti PM, Duarte AB, Orlando UD, Pasqualini ME, Solano AR, Lopez-Otin C, Podesta EJ. Functional interaction between acyl-CoA synthetase 4, lipooxygenases and cyclooxygenase-2 in the aggressive phenotype of breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maloberti P, Castilla R, Castillo F, Maciel FC, Mendez CF, Paz C, Podesta EJ. Silencing the expression of mitochondrial acyl-CoA thioesterase I and acyl-CoA synthetase 4 inhibits hormone-induced steroidogenesis. Febs J. 2005;272:1804–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cao Y, Pearman AT, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM. Intracellular unesterified arachidonic acid signals apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11280–11285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uchida Y, Kondo N, Orii T, Hashimoto T. Purification and properties of rat liver peroxisomal very-long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;119:565–571. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Uchiyama A, Aoyama T, Kamijo K, Uchida Y, Kondo N, Orii T, Hashimoto T. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding rat very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30360–30365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jia Z, Pei Z, Li Y, Wei L, Smith KD, Watkins PA. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: role of very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaffer JE, Lodish HF. Expression cloning and characterization of a novel adipocyte long chain fatty acid transport protein. Cell. 1994;79:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Roermund CW, Visser WF, Ijlst L, van Cruchten A, Boek M, Kulik W, Waterham HR, Wanders RJ. The human peroxisomal ABC half transporter ALDP functions as a homodimer and accepts acyl-CoA esters. FASEB J. 2008;22:4201–4208. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mihalik SJ, Steinberg SJ, Pei Z, Park J, Kim DG, Heinzer AK, Dacremont G, Wanders RJ, Cuebas DA, Smith KD, Watkins PA. Participation of two members of the very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase family in bile acid synthesis and recycling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24771–24779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pellicoro A, van den Heuvel FA, Geuken M, Moshage H, Jansen PL, Faber KN. Human and rat bile acid-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase are liver-specific peroxisomal enzymes: implications for intracellular bile salt transport. Hepatology. 2007;45:340–348. doi: 10.1002/hep.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heinzer AK, Watkins PA, Lu JF, Kemp S, Moser AB, Li YY, Mihalik S, Powers JM, Smith KD. A very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase-deficient mouse and its relevance to X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1145–1154. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Watkins PA. Very-long-chain Acyl-CoA Synthetases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1773–1777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Milger K, Herrmann T, Becker C, Gotthardt D, Zickwolf J, Ehehalt R, Watkins PA, Stremmel W, Fullekrug J. Cellular uptake of fatty acids driven by the ER-localized acyl-CoA synthetase FATP4. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4678–4688. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jia Z, Moulson CL, Pei Z, Miner JH, Watkins PA. Fatty acid transport protein 4 is the principal very long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase in skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20573–20583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wanders RJ, van Roermund CW, van Wijland MJ, Schutgens RB, Schram AW, Tager JM, van den Bosch H, Schalkwijk C. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: identification of the primary defect at the level of a deficient peroxisomal very long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase using a newly developed method for the isolation of peroxisomes from skin fibroblasts. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1988;11(Suppl 2):173–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01804228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wanders RJA, van Roermund CWT, van Wijland MJA, Schutgens RBH, Schram AW, Tager JM, van den Bosch H, Schalwijk C. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: Identification of the primary defect at the level of a deficient peroxisomal very long chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase using a newly developed method for the isolation of peroxisomes from skin fibroblasts. J Inher Metab Dis. 1988;11(Suppl 2):173–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01804228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hashmi M, Stanley W, Singh I. Lignoceroyl-CoASH ligase: enzyme defect in fatty acid beta-oxidation system in X-linked childhood adrenoleukodystrophy. FEBS Lett. 1986;196:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lazo O, Contreras M, Bhushan A, Stanley W, Singh I. Adrenoleukodystrophy: impaired oxidation of fatty acids due to peroxisomal lignoceroyl-CoA ligase deficiency. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;270:722–728. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lazo O, Contreras M, Hashmi M, Stanley W, Irazu C, Singh I. Peroxisomal lignoceroyl-CoA ligase deficiency in childhood adrenoleukodystrophy and adrenomyeloneuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7647–7651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mosser J, Douar AM, Sarde CO, Kioschis P, Feil R, Moser H, Poustka AM, Mandel JL, Aubourg P. Putative X-Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy Gene Shares Unexpected Homology with ABC Transporters. Nature. 1993;361:726–730. doi: 10.1038/361726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Makkar RS, Contreras MA, Paintlia AS, Smith BT, Haq E, Singh I. Molecular organization of peroxisomal enzymes: protein-protein interactions in the membrane and in the matrix. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;451:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yamada T, Shinnoh N, Kondo A, Uchiyama A, Shimozawa N, Kira J, Kobayashi T. Very-long-chain fatty acid metabolism in adrenoleukodystrophy protein- deficient mice. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2000;32:239–246. doi: 10.1385/cbb:32:1-3:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamada T, Taniwaki T, Shinnoh N, Uchiyama A, Shimozawa N, Ohyagi Y, Asahara H, Kira J. Adrenoleukodystrophy protein enhances association of very long-chain acyl-coenzyme A synthetase with the peroxisome. Neurology. 1999;52:614–616. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moulson CL, Martin DR, Lugus JJ, Schaffer JE, Lind AC, Miner JH. Cloning of wrinkle-free, a previously uncharacterized mouse mutation, reveals crucial roles for fatty acid transport protein 4 in skin and hair development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5274–5279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431186100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Herrmann T, Van Der Hoeven F, Grone HJ, Stewart AF, Langbein L, Kaiser I, Liebisch G, Gosch I, Buchkremer F, Drobnik W, Schmitz G, Stremmel W. Mice with targeted disruption of the fatty acid transport protein 4 (Fatp 4, Slc27a4) gene show features of lethal restrictive dermopathy. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1105–1115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Klar J, Schweiger M, Zimmerman R, Zechner R, Li H, Torma H, Vahlquist A, Bouadjar B, Dahl N, Fischer J. Mutations in the fatty acid transport protein 4 gene cause the ichthyosis prematurity syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Asayama K, Sandhir R, Sheikh FG, Hayashibe H, Nakane T, Singh I. Increased peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation and enhanced expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha in diabetic rat liver. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;194:227–234. doi: 10.1023/a:1006930513476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Durgan DJ, Smith JK, Hotze MA, Egbejimi O, Cuthbert KD, Zaha VG, Dyck JR, Abel ED, Young ME. Distinct transcriptional regulation of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms and cytosolic thioesterase 1 in the rodent heart by fatty acids and insulin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2480–2497. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01344.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Westerbacka J, Kolak M, Kiviluoto T, Arkkila P, Siren J, Hamsten A, Fisher RM, Yki-Jarvinen H. Genes involved in fatty acid partitioning and binding, lipolysis, monocyte/macrophage recruitment, and inflammation are overexpressed in the human fatty liver of insulin-resistant subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56:2759–2765. doi: 10.2337/db07-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kotronen A, Yki-Jarvinen H, Aminoff A, Bergholm R, Pietilainen KH, Westerbacka J, Talmud PJ, Humphries SE, Hamsten A, Isomaa B, Groop L, Orho-Melander M, Ehrenborg E, Fisher RM. Genetic variation in the ADIPOR2 gene is associated with liver fat content and its surrogate markers in three independent cohorts. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:593–602. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Askari B, Kanter JE, Sherrid AM, Golej DL, Bender AT, Liu J, Hsueh WA, Beavo JA, Coleman RA, Bornfeldt KE. Rosiglitazone inhibits acyl-CoA synthetase activity and fatty acid partitioning to diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol via a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-independent mechanism in human arterial smooth muscle cells and macrophages. Diabetes. 2007;56:1143–1152. doi: 10.2337/db06-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nemoto Y, Toda K, Ono M, Fujikawa-Adachi K, Saibara T, Onishi S, Enzan H, Okada T, Shizuta Y. Altered expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in aromatase-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1819–1825. doi: 10.1172/JCI9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Egawa T, Toda K, Nemoto Y, Ono M, Akisaw N, Saibara T, Hayashi Y, Hiroi M, Enzan H, Onishi S. Pitavastatin ameliorates severe hepatic steatosis in aromatase-deficient (Ar−/−) mice. Lipids. 2003;38:519–523. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yoshikawa T, Toda K, Nemoto Y, Ono M, Iwasaki S, Maeda T, Saibara T, Hayashi Y, Miyazaki E, Hiroi M, Enzan H, Shizuta Y, Onishi S. Aromatase-deficient (ArKO) mice are retrieved from severe hepatic steatosis by peroxisome proliferator administration. Hepatol Res. 2002;22:278–287. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(01)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yoshida Y, Singh I. Effect of Clofibrate on Peroxisomal Lignoceroyl-CoA Ligase Activity. Biochem Med Met Bio. 1990;43:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(90)90004-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamada J, Ogawa S, Horie S, Watanabe T, Suga T. Participation of peroxisomes in the metabolism of xenobiotic acyl compounds: comparison between peroxisomal and mitochondrial beta-oxidation of omega-phenyl fatty acids in rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;921:292–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vamecq J, Vallee L, Fontaine M, Lambert D, Poupaert J, Nuyts JP. CoA Esters of Valproic Acid and Related Metabolites Are Oxidized in Peroxisomes Through a Pathway Distinct from Peroxisomal Fatty and Bile Acyl-CoA beta-Oxidation. FEBS Lett. 1993;322:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81545-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Silva MF, Ruiter JP, Overmars H, Bootsma AH, van Gennip AH, Jakobs C, Duran M, Tavares de Almeida I, Wanders RJ. Complete beta-oxidation of valproate: cleavage of 3-oxovalproyl-CoA by a mitochondrial 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase. Biochem J. 2002;362:755–760. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Aarsland A, Berge RK. Peroxisome proliferating sulphur- and oxy-substituted fatty acid analogues are activated to acyl coenzyme A thioesters. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;41:53–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Panuganti SD, Penn JM, Moore KH. Hepatic enzymatic synthesis and hydrolysis of CoA esters of solvent-derived oxa acids. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2003;17:76–85. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Amigo L, McElroy MC, Morales MN, Bronfman M. Subcellular distribution and characteristics of ciprofibroyl-CoA synthetase in rat liver. Its possible identity with long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase. Biochem J. 1992;284(Pt 1):283–287. doi: 10.1042/bj2840283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lageweg W, Wanders RJ. Studies on the effect of fenoprofen on the activation and oxidation of long chain and very long chain fatty acids in hepatocytes and subcellular fractions from rat liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:79–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]