Abstract

Co-ruminating, or excessively discussing problems, with friends is proposed to have adjustment trade-offs. Co-rumination is hypothesized to contribute both to positive friendship adjustment and to problematic emotional adjustment. Previous single-assessment research was consistent with this hypothesis, but whether co-rumination is an antecedent of adjustment changes was unknown. A six-month longitudinal study with middle childhood to mid-adolescent youth examined whether co-rumination is simultaneously a risk factor (for depression and anxiety) and a protective factor (for friendship problems). For girls, a reciprocal relationship was found in which co-rumination predicted increased depressive and anxiety symptoms and increased positive friendship quality over time, which, in turn, contributed to greater co-rumination. For boys, having depressive and anxiety symptoms and high-quality friendships also predicted increased co-rumination. However, for boys, co-rumination predicted only increasing positive friendship quality and not increasing depression and anxiety. An implication of this research is that some girls at risk for developing internalizing problems may go undetected because they have seemingly supportive friendships.

Keywords: friendships, self-disclosure, friendship quality, depression, anxiety

Friendships have long been thought to play an important role in socioemotional development (see Bukowski, Newcomb, & Hartup, 1996; Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998). One aspect of friendships generally thought to be especially positive is that friends serve as sources of social support (e.g., Berndt, 1989; Rubin et al., 1998; Sullivan, 1953). However, it is possible that some support processes have costs as well as benefits. This possibility has been understudied as most research on social support focuses on its positive aspects.

In order to examine the idea that some social processes have both negative and positive influences on adjustment over time, we examined co-rumination in the friendships of children and adolescents. Co-rumination is a recently developed construct and is defined as “excessively discussing personal problems within a dyadic relationship” (Rose, 2002). The one published study of co-rumination (Rose, 2002) suggests that co-rumination in friendship may have adjustment trade-offs. That is, co-rumination was related to positive friendship quality but also to elevated internalizing symptoms. However, because only concurrent relations were tested, it is unknown whether co-rumination is an antecedent of adjustment outcomes. Addressing this question is crucial for determining whether co-rumination is a risk factor for some problems (emotional adjustment problems) but a protective factor for others (friendship problems).

To address this question, we tested the relations of co-rumination and adjustment over the course of a school year among middle childhood to mid-adolescent youth. Co-rumination in friendships was hypothesized to contribute to increases in positive friendship adjustment and problematic emotional adjustment over time. We also examined the possibility that initial friendship and emotional adjustment contribute to changes in co-rumination over time.

The Influence of Friendship Processes on Adjustment: Considering Co-Rumination

Much is known about the role of peer relations, including friendships, in the development of adjustment problems (Deater-Deckard, 2001; Parker, Rubin, Price, & DeRosier, 1995). This work largely focuses on protective functions of friendships, such as providing companionship, reliable alliances, and validation (Asher & Parker, 1989; Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995; Sullivan, 1953). Recently, more attention has been paid to the risks of friendships, such as those related to having deviant friends (e.g., Brendgen, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 2000) or experiencing jealousy in friendships (Parker, Low, Walker, & Gamm, 2005). In contrast to work that examines either protective or risk factors, very little attention has been paid to the idea that some friendship processes have both costs and benefits (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Considering such processes could contribute to a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of friendships.

Co-rumination was proposed to be a single peer process that could have both positive and negative effects on adjustment. As mentioned, support processes are generally thought to be positive and adaptive. Consistent with this view, perceptions of social support in general (e.g., Galambos, Leadbeater, & Barker, 2004; Jackson & Warren, 2000) and from friends in particular (e.g., Colarossi & Eccles, 2000) are related to lower internalizing symptoms in youth. However, there also are hints in the literature that some support processes are linked with maladjustment. For example, excessively seeking reassurance is related to emotional problems (e.g., Joiner, Alfano, & Metlasky, 1992; Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005). Over-involvement in others’ problems also is linked with depression (Gore, Aseltine, & Colten, 1993). The idea has been raised as well that, for some youth, sharing problems and concerns becomes too central of a focus in their relationships (Belle, 1989; Zahn-Waxler, 2000). This idea, however, was not studied systematically until the development of the co-rumination construct (Rose, 2002).

Co-rumination, or excessively discussing problems, is characterized by mutual encouragement of problem talk, rehashing problems, speculating about problems, and dwelling on negative affect (Rose, 2002). To illustrate, consider friends who talk to each other during all of the breaks at school about a perceived rejection from a peer or a romantic break up and then continue the conversation on the telephone all evening. These friends prompt one another to talk about the situation, revisit the details of what happened, wonder together about why it might have happened and what the repercussions will be, and talk about how sad or mad the situation made them. After the conversations, the friends may feel close to one another, but whether such a persistent focus on problems is beneficial emotionally is questionable.

We think of co-rumination as lying at the intersection of self-disclosure and rumination. Like self-disclosure, co-rumination involves sharing personal thoughts and feelings. However, whereas self-disclosure can involve any personal topic and can be brief, co-rumination involves an excessive focus on problems and concerns. Co-rumination and rumination are similar in that they both involve a negative focus on problems or negative affect. However, whereas rumination is a cognitive, solitary process, co-rumination is a social, conversational process.

To date, only one published study has examined co-rumination. In this study (Rose, 2002), a survey measure of co-rumination with same-sex friends was developed with third-, fifth-, seventh-, and ninth-grade youth. Consistent with research indicating that self-disclosure is linked with high-quality friendships (e.g., Camarena, Sarigiani, & Peterson, 1990; Parker & Asher, 1993), co-rumination was positively related to having high-quality, close friendships. However, consistent with research indicating that solitary ruminating is related to emotional problems (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994; Schwartz & Koenig, 1996), co-rumination also was related to higher internalizing symptoms (i.e., depressive and anxiety symptoms). This study also provided evidence of discriminant validity among the constructs of co-rumination, self-disclosure, and rumination.

Influence of Co-Rumination on Later Adjustment

The past study suggested that co-rumination was related to positive friendship adjustment and problematic emotional adjustment (Rose, 2002), but it had a critical limitation in that it was not possible to test the relations over time. Because co-rumination was proposed to be important due to its hypothesized influence on adjustment, it is crucial to demonstrate that co-rumination precedes changes in adjustment. In the current study, whether co-rumination contributes over time to changes in positive friendship quality and in depression and anxiety is examined.

In terms of friendships, theory suggests that self-disclosure strengthens relationships over time due to increased understanding and trust (Buhrmester & Prager, 1995). Likewise, co-rumination was predicted to increase positive friendship quality and emotional closeness between friends. Co-rumination also was expected to predict later depression and anxiety. Rumination predicts increased internalizing symptoms over time, presumably due to its negative focus (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994; Schwartz & Koenig, 1996). Because co-rumination also involves a persistent negative focus and interferes with activities that could offer distraction, co-rumination also was expected to predict increases in the negative affect characteristic of depression. Because co-rumination involves a perseverative focus on the details of problems, it also may cause problems to seem more significant and harder to resolve. This could lead to more worries and concerns about problems and associated anxiety symptoms.

Influences of Initial Adjustment on Later Co-Rumination

Although co-rumination originally was hypothesized to influence adjustment (Rose, 2002), it is plausible that friendship and emotional adjustment affect youth’s tendency to co-ruminate too. It is feasible that youth with high-quality friendships co-ruminate more over time. Youth may feel especially secure in high-quality friendships, which increases the likelihood they will be comfortable talking about problems frequently and in detail. Depressive and anxiety symptoms also may contribute to increased co-rumination. Youth with these symptoms have associated problems and troubles, which would provide material for co-rumination.

Friendship quality and emotional adjustment also may interact in predicting changes in co-rumination. That is, the combination of having a high-quality friendship and elevated depressive or anxiety symptoms may serve as a unique breeding ground for co-rumination. For example, youth with depressive or anxiety symptoms may only co-ruminate more over time if they have a high-quality friend with whom they feel especially comfortable.

Note too that the relations may be bi-directional. Researchers increasingly have become aware of transactional relations between peer relationships and adjustment (Rubin et al., 1998; Rudolph & Asher, 2000). In regards to co-rumination, youth who co-ruminate may develop higher-quality friendships and increased depression and anxiety, which, in turn, strengthen their co-ruminative styles. Transactional processes are especially important in terms of depression and anxiety because they could lead to escalating emotional adjustment problems over time.

Gender and Developmental Differences

Considerable research indicates that girls self-disclose more than boys (e.g., Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Parker & Asher, 1993; see Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Likewise, girls also were found to co-ruminate more than boys (Rose, 2002). This gender difference in co-rumination intensified in adolescence, which parallels other findings indicating that gender differences in self-disclosure strengthen during adolescence (see Buhrmester & Prager, 1995; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). These mean-level differences are expected to replicate in the current research.

A separate question is whether there are gender differences in the relations of co-rumination with adjustment. Given that girls strongly value close relationships (Maccoby, 1990; Rose & Rudolph, 2006), friendship behaviors may be especially meaningful to girls. If this is the case, co-rumination may have a particularly strong impact on girls’ evaluations of friendship quality and on their emotional well-being. Alternatively, because co-rumination is less common for boys, co-rumination may be very salient to boys when it does occur, resulting in co-rumination having a stronger impact on their adjustment. It also is possible that the relations of co-rumination with adjustment for girls and boys differ for children versus adolescents.

Method

Participants

Participants were third-, fifth-, seventh-, and ninth-grade youth in four Midwestern school districts. Of the 1,383 students eligible for participation, 1,048 received active parental consent and participated in the fall (Time 1). There was some attrition, but 999 youth participated in the spring (Time 2). For youth with relevant data, attrition analyses conducted. Youth who participated at both assessments were compared to youth who participated at Time 1 only in terms of all Time 1 variables (co-rumination, having a reciprocal friend, friendship quality, depression, anxiety). Youth who participated in both assessments scored lower on depression than youth who only participated at Time 1 (both assessments, M = .42, SD = .36; Time 1 only, M = .58, SD = .45; see later section for scoring information for depression). However, youth who participated in both assessments did not differ from youth who participated only at Time 1 in terms of co-rumination, having a reciprocal friend, friendship quality, or anxiety.

Also, some of the 999 youth who participated at both assessments were missing data for particular measures. To be included in the current study, youth had to have data for co-rumination, friendship participation, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms at Times 1 and 2. Although friendship quality was included in some analyses, youth were not required to have friendship quality data in order to be included in the sample (they were only required to have friendship quality data to be included in analyses involving friendship quality). More youth had missing data for friendship quality (about 10–15% at each time point) than other measures (typically less than 5% at each time point).1 We decided not to require that youth have friendship quality data to be included in the sample to maximize the number of youth included in analyses that did not involve friendship quality. In the section describing the friendship quality measure, details are given regarding the number of youth with friendship quality data at Times 1 and 2.

The final sample included 813 youth with co-rumination, friendship participation, depression, and anxiety data at Times 1 and 2. There were 212 third- (113 girls; 99 boys), 239 fifth- (115 girls, 124 boys), 165 seventh- (86 girls, 79 boys), and 197 ninth- (102 girls, 95 boys) grade youth. The sample was 86% European American, 10% African American, and about 1% each for Native American, Asian American, Hispanic American, and “other” (e.g., biracial). No information regarding participants’ parents’ education, occupation, or socioeconomic status was collected.

Many analyses in the Results involve subsets of the 813 youth. Because co-rumination is conceptualized and operationalized as occurring in same-sex friendships, we wanted to ensure that youth included in analyses involving co-rumination had at least one reciprocal same-sex friend. For example, to be included in an analysis involving Time 1 co-rumination, youth had to have at least one reciprocal same-sex friend at Time 1. We acknowledge that this is a conservative approach because it likely excludes some youth do have friends (e.g., with peers who are not at school). However, we felt more comfortable with this approach than a more liberal approach in which we might include data on friendship co-rumination for youth who do not have reciprocal friends. Likewise, for analyses involving friendship quality at a particular time point, youth had to have at least one reciprocal friend at that time point. Details regarding which youth were included in which analyses are given in the Results.2

Last, preliminary analyses tested if it was appropriate to group third- and fifth-graders together and seventh- and ninth-graders together for analyses. Grouping youth into two grade groups would increase parsimony and would be consistent with our interest in comparing children and adolescents. Analyses presented in the Results examining prospective relations of co-rumination and adjustment were first conducted to test differences between third- and fifth-graders and between seventh- and ninth-graders. Analyses tested: (a) the main effect of grade (third versus fifth or seventh versus ninth) on each variable (co-rumination, positive friendship quality, depression, anxiety), (b) whether grade moderated relations of gender with each variable, (c) whether grade moderated relations of co-rumination with later friendship quality, depression, or anxiety, and (d) whether grade moderated relations of friendship quality, depression, or anxiety with later co-rumination. Fewer differences between third- and fifth-graders and between seventh- and ninth-graders emerged than would be expected by chance, and they did not qualify the findings. Therefore, third- and fifth-graders were grouped together and referred to as children. Seventh- and ninth-graders were grouped together and referred to as adolescents.

Procedure

Questionnaires were group administered in the classrooms by a trained research assistant. Items were read aloud, and students followed along and answered questions. We returned to each school at least once to collect data with students who were absent for the initial data collection.

Measures

Friendship nominations

Youth completed a friendship nominations measure at Times 1 and 2. These data were used to determine which youth to include in analyses regarding co-rumination and to assign youth a friend to report on in terms of friendship quality. The measure used was similar to those used in past research (e.g., Hoza, Molina, Bukowski, & Sippola, 1995; Parker & Asher, 1993; Rose, 2002; Rose & Asher, 1999). Youth were given a list of classmates and circled the names of their three best friends. Of these friends, they put a star next to the name of their “very best friend.” The list of classmates presented to the third- and fifth-grade youth and to the seventh- and ninth-grade youth differed. Third- and fifth-grade youth were presented with the names of all students with parental consent in their self-contained classroom. Because the seventh- and ninth-graders switched classes during the day and could interact with any of their grademates, they were presented with a list of all students with parental consent in their grade.

Youth were considered to have a reciprocal best friend if one of the three friends who they circled also circled their name. Of the 813 youth with friendship nominations data, 604 (74%) had at least one reciprocal same-sex friendship at Time 1 and 613 (75%) had at least one reciprocal same-sex friendship at Time 2. These percentages are similar to past research using similar procedures (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993). Of the 813 youth, 523 had at least one reciprocal same-sex friend at both Times 1 and 2. Fewer than 5% of the identified friendships at each assessment were cross-sex. Cross-sex friendships were not considered because they were rare and because they likely have unique characteristics compared to same-sex friendships.

Co-Rumination

Participants responded to the 27-item Co-Rumination Questionnaire (Rose, 2002). Items assessed the extent to which youth typically co-ruminate with same-sex friends. Three items assessed each of nine content areas: (a) frequently discussing problems, (b) discussing problems instead of engaging in other activities, (c) encouragement by the focal child of the friend discussing problems, (d) encouragement by the friend of the focal child discussing problems, (e) discussing the same problem repeatedly, (f) speculation about problem causes, (g) speculation about problem consequences, (h) speculation about parts of the problem that are not understood, and (i) focusing on negative feelings. Examples are “When we talk about a problem that one of us has, we usually talk about that problem every day even if nothing new has happened” and “When we talk about a problem that one of us has, we try to figure out everything about the problem, even if there are parts that we may never understand.” Items assessed a more extreme form of problem discussion than items typically used to assess self-disclosure.

Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale. Co-rumination scores were the mean ratings of the 27 items. Scores for co-rumination within friendships were assigned at Time 1 to the 604 participants with at least one same-sex friend at Time 1. Time 2 scores were assigned to the 613 participants with at least one same-sex friend at Time 2. Cronbach’s alphas were high at Times 1 and 2 (both αs = .97).

Positive friendship quality

Youth responded to a shortened 18-item version of Parker and Asher’s (1993) Friendship Quality Questionnaire (FQQ; see Rose, 2002). Three items assessed each of the following qualities: validation and caring, conflict resolution, help and guidance, companionship and recreation, intimate exchange, and conflict and betrayal. Youth also responded to 7 emotional closeness items adapted from two other friendship measures (Bukowski et al., 1994; Camarena et al., 1990). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

As in past research (Parker & Asher, 1993; Rose, 2002; Rose & Asher, 1999, 2004), a customized questionnaire was created for each participant with the friend’s name inserted in each item. The friendship nominations data were used to choose each youth’s highest-priority friend whose name would be inserted in each questionnaire item. For youth with only one reciprocal friend, that friendship was the highest priority. For youth with more than one reciprocal friend, the following criteria were used to select the highest-priority friendship (see Rose, 2002; Rose & Asher, 1999, 2004). First priority was given to friendships in which both youth circled and starred the other. Priority was then given to friendships in which the youth circled and starred a friend who also circled (but did not star) the youth. Next, priority was given to friendships in which youth circled (but did not star) a friend who circled and starred the youth. Lowest priority was given to friends who circled but did not star one another. Youth without a reciprocal same-sex friendship reported on a classmate they nominated as a friend. However, consistent with past research (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993; Rose, 2002), these data were not used.

At Time 1, this system was used to assign youth their highest-priority friend to report on for friendship quality. At Time 2, if youth maintained a reciprocal friendship with the youth they reported on at Time 1, they reported on that friend again regardless of the friend’s priority level. If they did not maintain that friendship, they reported on their highest-priority Time 2 friendship.

As will be described in detail in the Results section, the primary analyses involving friendship quality (i.e., that examined longitudinal associations between co-rumination and friendship quality) involved either: (a) Time 1 friendship quality scores or (b) changes in friendship quality scores from Time 1 to Time 2. Therefore, at Time 1, friendship quality scores were assigned to all youth with friendship quality data available for a reciprocal friend at Time 1 (547 of the 604 youth with a same-sex friend at Time 1). At Time 2, it only was necessary to assign friendship quality scores to youth with Time 1 friendship quality data who also had a reciprocal friendship and friendship quality data at Time 2 (because Time 2 scores were used only when considering changes in friendship quality from Time 1 to Time 2). Of the 547 youth with friendship quality data at Time 1, 475 had at least one reciprocal friend at Time 2. Of the 475 youth who also had a reciprocal friend at Time 2, 420 had Time 2 friendship quality data. Of these 420 youth, 298 reported on the same friendship at Time 2 that they reported on at Time 1.

Consistent with past research (see Furman, 1996), youth were given a score for overall positive friendship quality. This score was the mean of the 12 FQQ items assessing validation and caring, conflict resolution, help and guidance, and companionship and recreation and the 7 emotional closeness items. The intimate exchange FQQ items were not used due to conceptual overlap with co-rumination. This meant that there was no item overlap between the positive friendship quality score (which did not include the intimate exchange items) and the co-rumination measure. Also, the conflict and betrayal items were not used because the present research focused on the impact of co-rumination on positive friendship features. The items used to create this score were identical to items used to assess positive friendship quality in the first co-rumination study (Rose, 2002). The resulting 19-item scale was internally consistent at both Time 1 (α = .94) and at Time 2 (α = .93).

Depression

Participants responded to 26 items of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). As in some previous studies (e.g., Cole, Martin, & Powers, 1997; Oldenburg & Kerns, 1997; Panak & Garber, 1992), the suicidal ideation item was dropped. The items were scored as 0, 1, or 2 with higher numbers indicating more severe symptoms.

The CDI assesses affective, somatic, behavioral/conduct, and school-related problems. Co-rumination was not expected to contribute to behavioral/conduct or school-related problems. Therefore, it was desirable to retain only items assessing affective and somatic symptoms. A factor analysis performed in the first co-rumination study (Rose, 2002) indicated that the affective and somatic symptoms loaded on one factor and the behavioral/conduct and school-related symptoms loaded on a second factor. In the present study, exploratory factor analyses (maximum likelihood method; promax rotation) also suggested two-factor solutions for each time point. The item loadings were examined to determine whether they replicated the first co-rumination study. The Time 1 results replicated the previous study. The Time 2 results replicated the previous study with the exception that the item regarding “doing things OK” that loaded on the behavioral/conduct and school-related problems factor in the past study loaded on the affective and somatic symptoms factor. Given that the item loadings at each assessment replicated or nearly replicated the findings from the past study, at each assessment, the 17 affective and somatic symptoms items that were retained in the first co-rumination study were retained. Also, in the past study and the current study, one item assessing friendship participation that loaded with the affective and somatic symptoms was dropped due to overlap with the separate assessment of friendship adjustment. The 17-item depressive symptoms scale was internally consistent at Time 1 (α = .86) and at Time 2 (α = .87; Ns = 813 at both time points).

Anxiety

Youth completed the 28-item Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978) by rating each item on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores were highly internally consistent at Times 1 and 2 (αs = .95 and Ns = 813 at both time points).

Results

Gender and Grade Group Differences in Co-Rumination and Adjustment

Co-rumination

Analyses examining gender and grade group differences in co-rumination were performed at Time 1 with the 604 youth with a Time 1 reciprocal same-sex friend and at Time 2 with the 613 youth with a Time 2 reciprocal same-sex friend. At each time point, a 2 (Gender) X 2 (Grade Group) ANOVA was conducted. At both time points, the main effects for gender were significant [Time 1, F (1, 600) = 94.01, p < .0001; Time 2, F (1, 609) = 85.77, p < .0001]. The grade group effect was significant at Time 1, F (1, 600) = 4.94, p < .05, but not Time 2, F (1, 609) = .55. However, at both time points, the Gender X Grade Group interactions were significant [Time 1, F (1, 600) = 13.89, p < .001; Time 2, F (1, 609) = 7.58, p < .01].

The means for girls and boys and the effect sizes for the gender differences are presented in Table 1. At each time point, girls scored higher than boys with the gender difference being larger among adolescents than children. The effect sizes were moderate in childhood and large in adolescence. Separate t tests indicated that the gender differences were significant for both adolescents [Time 1, t (246) = 9.93, p < .0001; Time 2, t (259) = 8.84, p < .0001] and children [Time 1, t (354) = 4.34, p < .0001; Time 2, t (350) = 4.68, p < .0001].

Table 1.

Girls’ and Boys’ Scores for Co-Rumination, Depression, Anxiety, and Positive Friendship Quality

| Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| n | M | n | M | d | n | M | n | M | d | |

| Co-Rumination | ||||||||||

| Children | 183 | 2.73 (.96) | 173 | 2.27 (1.05) | .46 | 183 | 2.52 (.89) | 169 | 2.05 (.99) | .50 |

| Adolescents | 139 | 2.85 (.85) | 109 | 1.81 (.78) | 1.27 | 151 | 2.66 (.82) | 110 | 1.80 (.71) | 1.11 |

| Depression | 416 | .43 (.36) | 397 | .41 (.36) | .06 | 416 | .41 (.37) | 397 | .40 (.36) | .03 |

| Anxiety | 416 | 2.43 (.85) | 397 | 2.23 (.88) | .23 | 416 | 2.34 (.85) | 397 | 2.11 (.82) | .28 |

| Positive Friendship Quality | ||||||||||

| Children | 164 | 3.08 (.79) | 156 | 2.89 (.96) | .22 | 135 | 3.17 (.68) | 120 | 2.86 (.85) | .41 |

| Adolescents | 123 | 3.14 (.66) | 104 | 2.44 (.78) | .98 | 93 | 3.13 (.64) | 72 | 2.34 (.78) | 1.12 |

Notes. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Means are presented separately for children and adolescents for constructs for which there were significant Gender X Grade Group interactions. The gender comparisons for each construct, except depression, were significant.

Depression

For the entire sample of 813 youth, a 2 (Gender) X 2 (Grade Group) ANOVA was conducted at Times 1 and 2 for depression. At each time point, significant effects were not found for gender [Time 1, F (1, 809) = .37; Time 2, F (1, 809) = .35], grade group [Time 1, F (1, 809) = .64; Time 2, F (1, 809) = 2.91], or their interaction [Time 1, F (1, 809) = .03; Time 2, F (1, 809) = .90]. Although the gender difference was not significant, the means for girls and boys and corresponding effect sizes are presented in Table 1 for comparison with other variables. Girls scored non-significantly higher than boys at both times.

Anxiety

A 2 (Gender) X 2 (Grade Group) ANOVA also was conducted at Times 1 and 2 for anxiety for the entire sample of 813 youth. At both time points, the main effects were significant for gender [Time 1, F (1, 809) = 11.48, p < .001; Time 2, F (1, 809) = 14.65, p < .0001] and grade group [Time 1, F (1, 809) = 27.08, p < .0001; Time 2, F (1, 809) = 11.65, p < .001]. The interactions were not significant [Time 1, F (1, 809) = .10; Time 2, F (1, 809) = .24]. The means for girls and boys and corresponding effect sizes for the gender differences are presented in Table 1. Although the effect sizes were relatively small, girls reported greater anxiety than boys. Children also reported greater anxiety than adolescents (Time 1, children M = 2.47, SD = .94, adolescents M = 2.16, SD = .74, d = .36; Time 2, children M = 2.32, SD = .94, adolescents M = 2.12, SD = .70, d = .24).

Positive friendship quality

A (Gender) X 2 (Grade Group) ANOVA was performed for youth with positive friendship quality scores at Time 1 (n = 547) and Time 2 (n = 420). At each time point, the effects were significant for gender [Time 1, F (1, 543) = 39.36, p < .0001; Time 2, F (1, 416) = 54.66, p < .0001], grade group [Time 1, F (1, 543) = 7.28, p < .01; Time 2, F (1, 416) = 13.94, p < .001], and the Gender X Grade Group interaction [Time 1, F (1, 543) = 12.75, p < .001; Time 2, F (1, 416) = 10.91, p < .01].

The means for girls and boys and the corresponding effect sizes are presented in Table 1. At each time point, girls scored higher than boys, with the gender differences being larger for adolescents than for children. The effects sizes were small to moderate for children and large for adolescents. Separate t tests conducted by grade group indicated significant gender differences for both adolescents [Time 1, t (225) = 7.31, p < .0001; Time 2, t (163) = 7.20, p < .0001] and children [Time 1, t (318) = 1.95, p = .05; Time 2, t (253) = 3.18, p < .01].

Correlations Among Co-Rumination, Depression, Anxiety, and Positive Friendship Quality

Correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 2. Two points should be highlighted. First, considerable across-time stability was found from the fall to the spring for co-rumination, depression, anxiety, and positive friendship quality. Second, at both time points, the results are consistent with the prior findings (Rose, 2002) in that significant positive concurrent associations were found between co-rumination and depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as between co-rumination and positive friendship quality.

Table 2.

Correlations among Time 1 and Time 2 Scores for Co-Rumination, Depression, Anxiety, and Positive Friendship Quality

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Rumination | Depression | Anxiety | Positive Friendship Quality | Co-Rumination | Depression | Anxiety | ||

|

| ||||||||

| N | ||||||||

| Time 1: | ||||||||

| Co-Rumination | 813 | -- | ||||||

| Depression | 813 | .13*** | ||||||

| Anxiety | 813 | .33**** | .67**** | |||||

| Positive Friendship Quality | 546 | .35**** | −.07 | .12** | ||||

| Time 2: | ||||||||

| Co-Rumination | 813 | .54**** | .20**** | .31**** | .29**** | |||

| Depression | 813 | .14**** | .66**** | .53**** | −.01 | .20**** | ||

| Anxiety | 813 | .24**** | .52**** | .63**** | .14** | .42**** | .67**** | |

| Positive Friendship Quality | 420 | .27**** | −.08 | .11* | .40**** | .26**** | −.09 | .09 |

Note.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

Longitudinal Associations of Initial Co-Rumination with Later Adjustment

Co-rumination as a predictor of later depressive and anxiety symptoms

Analyses first examined whether initial co-rumination predicted changes in depression over time. Because these analyses involved Time 1 co-rumination, youth had to have at least one reciprocal same-sex friendship at Time 1 in order to be included. Accordingly, a hierarchical regression analysis was performed for the 604 youth with at least one reciprocal same-sex friend at Time 1.

In this analysis, Time 2 depression was the dependent variable. In terms of independent variables, on the first step, Time 1 depression was entered (because Time 1 and Time 2 depression were correlated). On the second step, gender and grade group were entered as control variables. Of primary interest was the third step in which Time 1 co-rumination was entered. On step four, all two-way interactions among Time 1 co-rumination, gender, and grade group were entered. On the fifth step, the three-way interaction among Time 1 co-rumination, gender and grade group was entered. Of interest in the fourth and fifth steps was whether the main effect of co-rumination on changes in depression was moderated by gender and/or grade group. In this analysis and all subsequent regression analyses, all continuous predictor variables were centered (Aiken & West, 1991). The betas, t values, R2 and R2 change values are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Regression Analyses Examining Whether Initial (Time 1) Co-Rumination Predicts Later (Time 2) Depression and Anxiety

| DV = Time 2 Depression | DV = Time 2 Anxiety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| β | t value | R2 | R2 change | β | t value | R2 | R2 change | |

| Step 1: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Depression or Anxiety | .67 | 22.22**** | .4506 | — | .64 | 20.17**** | .4033 | — |

| Step 2: | ||||||||

| Gender | −.03 | .97 | .4518 | .0012 | −.08 | 2.46* | .4094 | .0061* |

| Grade Group | −.02 | .69 | .01 | .24 | ||||

| Step 3: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Co-Rumination | .07 | 2.26* | .4564 | .0046* | .03 | .98 | .4104 | .0010 |

| Step 4: | ||||||||

| Gender X Grade Group | −.04 | .79 | .4597 | .0033 | .00 | .01 | .4164 | .0060† |

| Gender X T1 Co-Rumination | −.08 | 1.79† | −.11 | 2.45* | ||||

| Grade Group X T1 Co-Rumination | −.01 | .16 | .00 | .06 | ||||

| Step 5: | ||||||||

| Gender X Grade Group | .06 | 1.03 | .4606 | .0009 | .03 | .56 | .4167 | .0003 |

| X T1 Co-Rumination | ||||||||

Notes. For the regression analysis in which Time 2 depression was the DV, Time 1 depression was entered as a predictor on the first step. For the regression analysis in which Time 2 anxiety was the DV, Time 1 anxiety was entered as a predictor on the first step. The total R2 value from each of the models tested was significant.

p ≤ .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

As would be expected, Time 1 depression was a significant positive predictor of Time 2 depression on step 1. Step 2 was not significant, with neither gender nor grade group being significant predictors. Notably, step 3 was significant, with Time 1 co-rumination predicting increases in depression over time. Step 4 was not significant, and none of the individual two-way interactions on this step reached the traditional level of significance. However, the interaction between Time 1 co-rumination and gender on this step approached significance (more information about this interaction is given below). Last, step 5, which tested the three-way interaction among Time 1 co-rumination, gender, and grade group, was non-significant.

A hierarchical regression analysis next tested whether co-rumination predicted changes in anxiety over time. Time 1 anxiety was the dependent variable. The predictors were Time 1 anxiety (step 1), gender and grade group (step 2), Time 1 co-rumination (step 3), all two-way interactions among Time 1 co-rumination, gender, and grade group (step 4), and the three-way interaction (step 5). The betas, t values, R2 and R2 change values are presented in Table 3.

Step 1 was significant with Time 1 anxiety predicting greater Time 2 anxiety. Step 2 also was significant. On this step, gender significantly predicted Time 2 anxiety, with girls scoring higher than boys, but grade group was not a significant predictor. Step 3, which tested the effect of co-rumination, was not significant. However, step 4 was marginally significant. On step 4, the interaction between gender and Time 1 co-rumination was significant. The other two-way interactions were not significant. The three-way interaction on step 5 also was not significant.

Although the effects did not always reach the traditional significance level, the findings across these analyses suggest that there could be meaningful gender differences in the relations between co-rumination and internalizing symptoms. Given that (a) significant interactions are highly difficult to detect with non-experimental designs, especially prospective designs (e.g., McClelland & Judd, 1993) and (b) the pattern of results across the two separate analyses indicated that gender may be an important moderator, the decision was made to probe the interactions with gender.

First, separate hierarchical regression analyses were conducted for girls and boys with Time 2 depression as the dependent variable. Time 1 depression was entered on step 1, grade group was entered on step 2, and Time 1 co-rumination was entered on step 3. The betas, t values, R2 and R2 change values are presented for girls and boys in Table 4. As expected, for girls and boys, Time 1 depression was a significant positive predictor on step 1 and grade group was not a significant predictor on step 2. Interestingly, step 3 was significant only for girls, with Time 1 co-rumination predicting increases in girls’ depression. Step 3 was not significant for boys. In fact, for boys, the beta for Time 1 co-rumination was very near zero.

Table 4.

Summary of Regression Analyses Examining Whether Initial (Time 1) Co-Rumination Predicts Later (Time 2) Depression and Anxiety Separately for Girls and Boys

| DV = Time 2 Depression | DV = Time 2 Anxiety | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| β | t value | R2 | R2 change | β | t value | R2 | R2 change | |

| Girls

| ||||||||

| Step 1: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Depression or Anxiety | .67 | 16.06**** | .4463 | — | .64 | 15.06**** | .4149 | — |

| Step 2: | ||||||||

| Grade Group | .01 | .14 | .4464 | .0001 | .01 | .30 | .4151 | .0002 |

| Step 3: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Co-Rumination | .11 | 2.73** | .4591 | .0127** | .10 | 2.15* | .4235 | .0084* |

|

| ||||||||

| Boys

| ||||||||

| Step 1: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Depression or Anxiety | .67 | 15.18**** | .4515 | — | .59 | 12.35**** | .3527 | — |

| Step 2: | ||||||||

| Grade Group | −.05 | 1.22 | .4544 | .0029 | .00 | .03 | .3527 | .0000 |

| Step 3: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Co-Rumination | .01 | .21 | .4545 | .0000 | −.04 | .82 | .3542 | .0015 |

Notes. For the regression analyses in which Time 2 depression was the DV, Time 1 depression was entered as a predictor on the first step. For the regression analyses in which Time 2 anxiety was the DV, Time 1 anxiety was entered as a predictor on the first step. The total R2 value from each of the models tested was significant.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

The analyses were then repeated with anxiety as the dependent variable instead of depression. The results of this analysis also are summarized in Table 4. For both girls and boys, Time 1 anxiety was a significant positive predictor of Time 2 anxiety on step 1, and grade group was not a significant predictor on step 2. Again, step 3 was significant for girls only. For girls, Time 1 co-rumination was a significant predictor of increases in anxiety. For boys, step 3 was not significant with the beta for Time 1 for co-rumination actually being near zero and negative.

Co-rumination as a predictor of later positive friendship quality

Analyses next examined whether co-rumination predicted changes in friendship quality. A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with the 420 youth with a friend at Time 1 (because the analyses involved Time 1 co-rumination) and friendship quality data at Times 1 and 2. Time 2 positive friendship quality was the dependent variable. Predictors were Time 1 positive friendship quality (step 1), gender and grade group (step 2), Time 1 co-rumination (step 3), the two-way interactions among gender, grade group, and Time 1 co-rumination (step 4), and the three-way interaction (step 5). The betas, t values, R2 and R2 change values are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of Regression Analyses Examining Whether Initial (Time 1) Co-Rumination Predicts Later (Time 2) Positive Friendship Quality

| DV = Time 2 Positive Friendship Quality (n = 420) | DV = Time 2 Positive Friendship Quality (n = 298) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| β | t value | R2 | R2 change | β | t value | R2 | R2 change | |

| Step 1: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Positive Friendship Quality | .40 | 8.95**** | .1610 | — | .50 | 9.91**** | .2491 | — |

| Step 2: | ||||||||

| Gender | −.23 | .5.14**** | .2251 | .0641**** | −.18 | 3.53*** | .2864 | .0373*** |

| Grade Group | −.13 | 3.08** | −.11 | 2.20* | ||||

| Step 3: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Co-Rumination | .09 | 1.99* | .2324 | .0073* | .11 | 2.08* | .2968 | .0104* |

| Step 4: | ||||||||

| Gender X Grade Group | −.12 | 1.63 | .2421 | .0097 | −.07 | .84 | .3100 | .0132 |

| Gender X T1 Co-Rumination | −.04 | .63 | .06 | .77 | ||||

| Grade Group X T1 Co-Rumination | .04 | .68 | .10 | 1.46 | ||||

| Step 5: | ||||||||

| Gender X Grade Group | −.09 | 1.09 | .2443 | .0022 | −.13 | 1.42 | .3148 | .0048 |

| X T1 Co-Rumination | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001. The total R2 value from each of the models tested was significant.

Time 1 positive friendship quality was a significant positive predictor of Time 2 positive friendship quality on step 1. Step 2 also was significant, with girls scoring significantly higher than boys and children scoring significantly higher than adolescents (adolescents’ scores were lower than children due to the low scores of adolescent boys; see Table 1 for means). Of primary interest, step 3 was significant, with Time 1 co-rumination predicting increases in positive friendship quality. Steps 4 and 5 were non-significant as were all of the individual effects for the two- and three-way interactions on these steps.

Last, this analysis was repeated using the 298 participants who reported on the same friendship at Times 1 and 2. The results replicated those found with the 420 participants and are summarized in Table 5. Time 1 positive friendship quality (step 1) and gender and grade group (step 2) again were significant predictors. Most importantly, step 3 was significant, with Time 1 co-rumination predicting increases in positive friendship quality within a specific friendship over time. Steps 4 and 5 and all of the individual interactions were non-significant.3

Longitudinal Associations of Initial Adjustment with Later Co-Rumination

Analyses next tested whether initial emotional and friendship adjustment predicted later co-rumination. The analyses included the 474 youth with a reciprocal same-sex friend at Time 1 and Time 2 (because the analyses involved Time 1 and 2 co-rumination) and Time 1 friendship quality data.

A hierarchical regression analysis was first performed to test whether depression, positive friendship quality, and their interaction predicted changes in co-rumination. Time 2 co-rumination was the dependent variable. In terms of predictor variables, Time 1 co-rumination was entered on step 1. Gender and grade group were entered on step 2. Time 1 depression and Time 1 positive friendship quality were entered on step 3. This step tested whether the main effects of depression and/or positive friendship quality predicted changes in co-rumination. Because the interactive effect between depression and positive friendship quality was of particular interest, this interaction was entered by itself on step 4. On step 5, the remaining two-way interactions among gender, grade group, Time 1 depression, and Time 1 positive friendship quality were entered. On step 6, all three-way interactions among gender, grade group, Time 1 depression, and Time 1 positive friendship quality were entered. On step 7, the four-way interaction was entered. The betas, t values, R2 and R2 change values are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of Regression Analyses Examining Whether Initial (Time 1) Friendship and Emotional Adjustment Predict Later (Time 2) Co-Rumination

| DV = Time 2 Co-Rumination | DV = Time 2 Co-Rumination | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| β | t value | R2 | R2 change | β | t value | R2 | R2 change | ||

| Step 1: | Step 1: | ||||||||

| Time 1 Co-Rumination | .54 | 14.00**** | .2933 | — | Time 1 Co-Rumination | .54 | 14.00**** | .2933 | — |

| Step 2: | Step 2: | ||||||||

| Gender | −.19 | 4.93**** | .3323 | .0390**** | Gender | −.19 | 4.93**** | .3323 | .0390**** |

| Grade Group | .05 | 1.37 | Grade Group | .05 | 1.37 | ||||

| Step 3: | Step 3: | ||||||||

| Depression | .11 | 3.04** | .3511 | .0188** | Anxiety | .15 | 3.79*** | .3580 | .0257**** |

| Positive Friendship Quality | .10 | 2.46* | Positive Friendship Quality | .09 | 2.21* | ||||

| Step 4: | Step 4: | ||||||||

| Depression | .03 | .84 | .3521 | .0010 | Anxiety | .08 | 2.03* | .3636 | .0056* |

| X Positive Friendship Quality | X Positive Friendship Quality | ||||||||

| Step 5: | Step 5: | ||||||||

| Gender X Grade Group | −.10 | 1.57 | .3585 | .0064 | Gender X Grade Group | −.11 | 1.74 | .3702 | .0066 |

| Gender X Depression | −.03 | .61 | Gender X Anxiety | −.01 | .12 | ||||

| Grade Group X Depression | .03 | .63 | Grade Group X Anxiety | .05 | .96 | ||||

| Gender X Positive Friendship | −.06 | .89 | Gender X Positive Friendship | −.04 | .65 | ||||

| Grade Group X Positive | −.07 | 1.39 | Grade Group X Positive | −.06 | 1.15 | ||||

| Friendship Quality | Friendship Quality | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001. None of the higer-order interactions entered on subsequent steps were significant. The total R2 value from each of the models tested was significant.

On step 1, Time 1 co-rumination was a significant positive predictor of Time 2 co-rumination. Step 2 also was significant; gender was significant, with girls scoring higher than boys, but grade group was not significant. Step 3 was significant, with both Time 1 depression and positive friendship quality being significant predictors. These findings indicated that depression and positive friendship quality each predicted increases in co-rumination. However, on step 4, the interaction between Time 1 depression and Time 1 positive friendship quality was not significant. Steps 5, 6, and 7 and all of the individual interactive effects were not significant.

Last, a parallel hierarchical regression analysis was conducted in which anxiety was a predictor rather than depression. The dependent variable was Time 2 co-rumination. The predictors were Time 1 co-rumination (step 1), gender and grade group (step 2), Time 1 anxiety and Time 1 positive friendship quality (step 3), the interaction between Time 1 anxiety and Time 1 positive friendship quality (step 4), all other two-way interactions among gender, grade group, Time 1 anxiety, and Time 1 positive friendship quality (step 5), all three-way interactions (step 6), and the four-way interaction (step 7). The results are summarized in Table 6.

As in the prior analysis, Time 1 co-rumination was a significant positive predictor on step 1. Step 2 also was significant; gender was significant, with girls scoring higher than boys, but grade group was not significant. Step 3 was significant, with Time 1 anxiety and positive friendship quality each significantly predicting increased co-rumination. Moreover, step 4, which tested the interaction between Time 1 anxiety and positive friendship quality, was significant. Steps 5, 6, and 7 and all of the individual interactive effects on these steps were not significant.

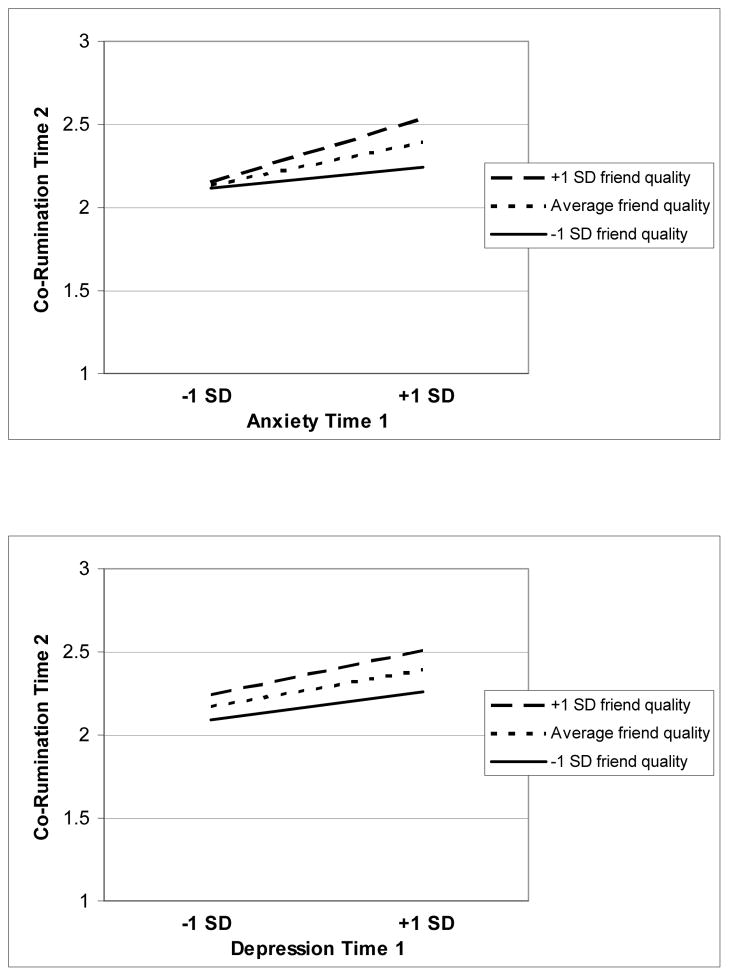

The significant interaction between Time 1 anxiety and positive friendship quality was probed (Aiken & West, 1991). In particular, simple slope analyses tested the effect of Time 1 anxiety symptoms on Time 2 co-rumination for youth who scored low (−1 SD), average (M), and high (+1 SD) on positive friendship quality. The strongest effect was found for youth who had high positive friendship quality, with Time 1 anxiety significantly predicting increased co-rumination over time, β = .19, t (467) = 4.27, p < .0001. A weaker significant effect of Time 1 anxiety on increasing co-rumination emerged for youth with average positive friendship quality, β = .13, t (467) = 3.43, p < .001. Time 1 anxiety was not related to later co-rumination for youth with low levels of positive friendship quality, β = .06, t (467) = 1.16.

This interaction is depicted graphically in Figure 1. As can be seen, youth with low Time 1 anxiety were similar in their Time 2 co-rumination scores regardless of their positive friendship quality scores. In addition, youth with high Time 1 anxiety who had low Time 1 positive friendship quality also had Time 2 co-rumination scores that were similar to youth with low Time 1 anxiety. In contrast, the highest Time 2 co-rumination scores were found for youth who had both high Time 1 anxiety and high Time 1 positive friendship quality. For comparison, the non-significant interaction between Time 1 depression and Time 1 positive friendship quality also was graphed in Figure 1. As can be seen, greater Time 2 co-rumination scores were found for youth with higher Time 1 depression scores and for youth with higher Time 1 positive friendship quality scores. However, the effects of Time 1 depression and Time 1 positive friendship quality on Time 2 co-rumination were not dependent on one another.

Figure 1.

The top panel illustrates the effects of Time 1 anxiety symptoms and Time 1 positive friendship quality in predicting Time 2 co-rumination. The bottom panel illustrates the effects of Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 1 positive friendship quality in predicting Time 2 co-rumination.

Discussion

The current study provided a major extension of past research by examining the temporal ordering of the relations between co-rumination and adjustment. Because co-rumination among friends may seem like a positive support process, it was important to learn whether co-rumination actually leads to negative as well as positive outcomes. In fact, a primary motivation for the study of co-rumination was the idea that co-rumination could be a risk factor for some adjustment problems but a protective factor for others. The current research provided the first test of whether co-rumination actually precedes changes in adjustment over time.

The findings of the present study were consistent with the proposition that co-rumination contributes to adjustment trade-offs over time. On the positive side, co-rumination predicted increases in feelings of closeness and positive friendship quality. It is reasonable that when friends engage in this intimate and intense form of disclosure they come to view their relationship in an increasingly positive light. However, for girls, there was a trade-off in that co-rumination also predicted increasing depressive and anxiety symptoms. Although social support is generally expected to protect against emotional problems (Nestmann & Hurrelmann, 1994), the current findings suggest that when support processes involve talking about problems so extensively, the effect on emotional adjustment may be negative rather than positive.

It is noteworthy that the effects of co-rumination on depression and anxiety held only for girls. This finding suggests that friendships may play an ironic role in the development of girls’ internalizing problems. Girls’ intentions when co-ruminating may be to give and seek positive support. However, these conversations appear to contribute to increased depression and anxiety. An important future direction will be to replicate this finding and to consider why co-rumination may be a stronger risk factor for girls than boys. For instance, co-rumination may lead girls to think about problems in a way that is different from boys and more closely linked with emotional problems. As an example, girls are found to be especially likely to take personal responsibility for certain failure experiences (e.g., Pomerantz & Ruble, 1998). Similarly, co-rumination may make problems more salient, and girls may be more likely than boys to make internal attributions about them. Importantly, past research indicates that certain attributions, including internal attributions, are linked with heightened internalizing symptoms (e.g., Stevens & Prinstein, 2005).

Another important extension was that initial adjustment affected youth’s tendency to co-ruminate. Positive friendship quality, depression, and anxiety each predicted increases in co-rumination. Also, an interesting interactive effect emerged between anxiety and friendship quality. Anxiety predicted increased co-rumination for youth with higher-quality friendships, but was not related to later co-rumination for youth with low-quality friendships. Having anxiety symptoms (and, presumably, associated heightened levels of worries and concerns) and a high-quality friend to talk to may provide a uniquely reinforcing context for co-rumination.

In contrast to the interactive effect between anxiety and positive friendship quality, depression and positive friendship quality did not interact in predicting later co-rumination. Instead, depression and positive friendship quality had separate, additive effects on increases in co-rumination over time. This difference between anxiety and depression was not predicted and is somewhat difficult to explain. However, one way to think about the difference is to consider why anxious youth, but not depressed youth, might inhibit co-rumination when their friendship is of lower quality. Perhaps the heightened worries and concerns that anxious youth experience generalize to worries and concerns about the status of their friendship. If this is the case, then anxious youth may refrain from co-ruminating when their friendship is of low quality because they worry that burdening their friend with their problems will have negative implications for the future of the relationship. In contrast, if depressed youth do not share these worries, they may not refrain from co-ruminating even when their friendship is of poor quality.

Considering all of the prospective relations together suggests that co-rumination is operating somewhat differently for girls and boys. Among girls, transactional relations were found between co-rumination and adjustment. For girls, co-rumination predicted increasing positive friendship quality and increasing depressive and anxiety symptoms over time, and positive friendship quality, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms (among youth with higher-quality friendships) each predicted increased co-rumination over time. Clearly, this is a vicious cycle for girls, and it is likely one that will be difficult to stop. Given that adolescent girls strongly value close relationships (e.g., Benenson & Benarroch, 1998; see Buhrmester, 1996), they may find the positive effects of co-rumination on their friendship quality to be reinforcing.

For boys, positive friendship quality, depression, and anxiety (among youth with higher-quality friendships) also predicted increasing co-rumination. However, co-rumination only was related to increasing positive friendship quality and not to changes in internalizing symptoms. These findings suggest that co-rumination may not be a risk factor for emotional problems for boys and, in fact, may be a positive process that leads to closer dyadic friendships.

Consider too the patterns of prospective relations between co-rumination and adjustment in conjunction with the patterns of mean-level gender differences. First, girls scored higher than boys on both co-rumination and positive friendship quality, and these differences were stronger for adolescents than children. Given that girls co-ruminate more than boys and that co-rumination contributed to increasing positive friendship quality, the findings suggest that co-rumination may be one factor that helps to explain why girls’ friendships are characterized by greater positive friendship quality than boys’ friendships, particularly in adolescence.

In terms of internalizing symptoms, gender and developmental differences also were found for anxiety. Girls scored higher on anxiety than boys, and children scored higher than adolescents. These results fit with research indicating that girls are more anxious than boys, but that anxiety decreases with age for girls and boys (Dadds, Perrin, & Yule, 1998; Turgeon & Chartrand, 2003). Because the grade differences found for co-rumination were not consistent with those found for anxiety, co-rumination does not help explain why anxiety decreases with age. However, given that co-rumination contributed to increased anxiety for girls, girls’ greater co-rumination may help to explain their greater anxiety during this developmental period.

Last, neither gender nor grade group differences were found for depression. Past research indicates stability in depression for boys and increases for girls as girls move through adolescence (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). However, the oldest girls in this sample were about fourteen and may not have been quite old enough to demonstrate this rise in depressive symptoms.4 Nevertheless, the relatively high levels of co-rumination among the adolescent girls in this sample may contribute to increased depression as they proceed through adolescence.

Although the current study contributes significantly to our understanding of the impact of friendships on youth’s well-being, there are limitations of the research. The longitudinal design was a strength of the study, but following youth for longer than six months would be useful. The study aimed to predict changes in friendship quality, depression, anxiety, and co-rumination over time. This was quite challenging given the stability of these constructs over six months. Co-rumination did predict changes in friendship and emotional adjustment, which predicted changes in co-rumination. However, the magnitude of these effects was small. If future research involved a longer time period, the stability should weaken, leaving more unaccounted for variance at the later assessment that could be predicted from variables from the initial assessment.

In terms of the strength of the relations, it also is acknowledged that co-rumination is only one of the multitude of factors affecting youth adjustment, which also helps to explain the modest effects. In fact, given that co-rumination has both positive and negative influences on adjustment, it is not surprising for these effects to be more subtle than effects of behaviors or characteristics that are more purely adaptive or maladaptive. Importantly, though, small effects have greater applied significance when they are bi-directional. For example, for girls, co-rumination may only predict small increases in depression and anxiety over six months. However, these small increases in depression and anxiety, in turn, should predict an increase in co-rumination, which should contribute to further increases in depression and anxiety. In this way, the bi-directional influences have the potential to create a snowball effect that contributes to adjustment changes over time that are of considerable practical importance.

The current assessment of co-rumination also may have led to underestimating some effects. Youth reported on co-rumination with friends in general rather than with a particular friend. This approach could be seen as analogous to research assessing social behavior in the peer group in general (e.g., Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). The assumption of both approaches is that youth have at least somewhat stable interpersonal styles that they carry across interactions. In regards to co-rumination, we suspect there are reasonably stable individual differences in the tendency to co-ruminate. Nevertheless, there also is likely variation across relationships (e.g., based on the partner’s tendency to co-ruminate). As such, the present study provided a conservative test of the relation of co-rumination with the quality of a particular friendship. In future research, if co-rumination and friendship quality are each assessed within the context of the same friendship, their relationship could be considerably stronger.

Involving different methods and samples also will be important in future studies. Self-reports were employed in the present study. On the positive side, this allowed for a large sample and high participation rate. However, verifying these results with other methods is important. For example, assessing co-rumination with an observational assessment would be useful. Replicating the findings with outside assessments of emotional adjustment, such as parent reports or clinical interviews will be important as well. Co-rumination also should be considered in samples that are more diverse in terms of race/ethnicity.

Finally, future research should consider co-rumination in regards to other aspects of friendships and the larger social context. Consider other friendship features, such as conflict. Co-rumination can involve sharing highly personal information. Such sharing could lead friends to become increasingly alike in their perceptions and to have fewer conflicts. However, if a friend discloses this personal information to others, greater conflict could result. The present study focused on positive aspects of friendships because a relatively direct link was expected between co-rumination and positive friendship quality. However, future research assessing what youth disclose and what the friend does with this knowledge will be useful for more fully understanding co-rumination in friendships, including the impact of co-rumination on conflict.

Also, how friends manage personal knowledge shared in the context of co-rumination could have implications for their status in the peer group. Youth who disclose friends’ personal information to hurt them could be perceived as relationally aggressive and be disliked. However, growing evidence suggests that some youth use relational aggression, such as gossiping, strategically to increase their social dominance and perceived popularity (e.g., by strengthening their ties with high-status peers; see Cillessen & Rose, 2005). Accordingly, some youth may use information gained through co-rumination deliberately to increase their social standing.

In closing, despite the limitations of the current study, the present research was useful for highlighting the idea that we need to adopt a careful, nuanced view when evaluating the role of friendships and social support in the lives of youth. Past studies led us to believe that we should worry more about socially isolated youth than youth with friendships, especially if the friendships involved high levels of self-disclosure and social support (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1993; see Newcomb & Bagwell, 1995). As a result, youth in friendships characterized by co-rumination may go undetected by adults, thus leaving them vulnerable to the development of emotional adjustment problems. The current findings caution us against being lulled into a false sense of security about youth, especially girls, with seemingly supportive friendships.

Acknowledgments

The research was partially supported by a Research Board Grant from the University of Missouri – Columbia and by NIMH grants R03 MH 63753 and R01 MH 073590 awarded to Amanda J. Rose.

Footnotes

The greater amount of missing friendship quality data was related to the method of assessing friendship quality. The friendship quality measure was customized for youth with a friend’s name in each item. If youth missed the first data collection session in which they nominated friends, a measure could not be customized for the second session. Therefore, youth were missing friendship quality data if they missed either the first or second session. Even if they attended the make-up session for absent youth, a customized measure still could not be made for them if they had missed the first session in which youth nominated friends. For other measures, youth only had missing data if they missed the session in which that measure was administered.

The primary analyses testing the reciprocal relations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment were repeated in supplementary analyses using youth who had been excluded because they did not have a reciprocal friend. Most of the hypothesized relations that were significant in the Results section using youth who were confirmed as having reciprocal friends were weaker and non-significant in the sample of excluded youth who did not have friends. Co-rumination is conceptualized as a dyadic process between friends and, therefore, should have the most salient effects for individuals with true, reciprocal friendships.

The 298 participants in this analysis reported on stable friendships, but many other youth did not have stable friendships. Accordingly, it also was possible to test whether initial co-rumination was related to friendship stability. Although no hypotheses had been put forth, in order to be comprehensive, a t test examined whether youth with stable versus unstable friendships differed in terms of Time 1 co-rumination. However, these groups did not differ.

Examination of the means also revealed similar depression scores for girls in the seventh and ninth grade who were grouped together in the adolescent grade group.

Appreciation is expressed to the students, teachers, administrative assistants, and administrators of Ashland, Fayette, Fulton, and Moberly public school districts in Missouri. We also thank Lance Swenson for his assistance with data collection.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Parker JG. The significance of peer relationship problems in childhood. In: Schneider BH, Attili G, Nadel J, Weissberg RP, editors. Social competence in developmental perspective. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1989. pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Belle D. Gender differences in children’s social networks and supports. In: Belle D, editor. Children’s social networks and social supports. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Benenson JF, Benarroch D. Gender differences in responses to friends’ hypothetical greater success. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1998;18:192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Obtaining support from friends during childhood and adolescence. In: Belle D, editor. Children’s social networks and social supports. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 308–331. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. Deviant friends and early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Need fulfillment, interpersonal competence, and the developmental contexts of early adolescent friendship. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 158–185. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58:1101–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Prager K. Patterns and functions of self-disclosure during childhood and adolescence. In: Rotenberg KJ, editor. Disclosure processes in children and adolescents. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 10–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Camarena PM, Sarigiani PA, Peterson AC. Gender-specific pathways to intimacy in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1990;19:19–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01539442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Rose AJ. Understanding popularity in the peer system. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Colarossi LG, Eccles JS. A prospective study of adolescents’ peer support: Gender differences and the influence of parental relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B. A competency-based model of child depression: A longitudinal study of peer, parent, teacher, and self-evaluations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1997;38:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66:710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Perrin S, Yule W. Social desirability and self-reported anxiety in children: An analysis of the RCMAS Lie Scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:311–317. doi: 10.1023/a:1022610702439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Annotation: Recent research examining the role of peer relationships in the development of psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:565–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colten ME. Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1993;3:101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Molina BSG, Bukowski WM, Sippola LK. Peer variables as predictors of later childhood adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:787–802. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Y, Warren JS. Appraisal, social support, and life events: Predicting outcome behavior in school-age children. Child Development. 2000;71:1441–1457. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Alfano MS, Metlasky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Multi-Health Systems; North Tonawanda, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestmann F, Hurrelmann K, editors. Social networks and social support in childhood and adolescence. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb AF, Bagwell CL. Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:306–347. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Parker LE, Larson J. Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:92–104. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg CM, Kerns KA. Associations between peer relationships and depressive symptoms: Testing moderator effects of gender and age. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1997;17:319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Panak WF, Garber J. Role of aggression, rejection, and attributions in the prediction of depression in children. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Low CM, Walker AR, Gamm BK. Friendship jealousy in young adolescents: Individual differences and links to sex, self-esteem, aggression, and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:235–250. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Rubin KH, Price JM, DeRosier ME. Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 2: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Oxford: Wiley; 1995. pp. 96–161. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Ruble DN. The role of maternal control in the development of sex differences in child self-evaluative factors. Child Development. 1998;69:458–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I Think and What I Feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73:1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children’s goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:69–79. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR. Children’s strategies and goals in response to help-giving and help-seeking tasks within a friendship. Child Development. 2004;75:749–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]