Abstract

Dating violence is a prevalent problem. Research demonstrates that males and females are victimized at comparable rates in their dating relationships and experience a number of mental health and relationship problems. Less research has examined male dating violence victimization, its association to mental health and relationship satisfaction, and whether coping styles influence mental health symptoms and relationship satisfaction among victims. The current study examined physical and psychological aggression victimization, adjustment (posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and relationship satisfaction), and problem-focused and emotion-focused coping among heterosexual college males in a current dating relationship (n = 184). Results identified that psychological victimization was associated with posttraumatic stress and relationship discord above and beyond physical victimization. Interaction findings identified that psychological victimization was associated with increased posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms at high levels of problem-focused coping, whereas psychological victimization was associated with less relationship satisfaction at low levels of emotion-focused coping. Implications of these findings for future research are discussed.

Keywords: dating violence, posttraumatic stress, relationship satisfaction, coping

Dating violence is a serious and prevalent problem among young dating couples. Dating violence victimization is associated with a wealth of negative consequences (Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008), including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Harned, 2001; Hines, 2007), decreased relationship satisfaction (Kaura & Lohman, 2007), depression (Shorey, Sherman, et al., 2011), increased substance use (Shorey, Rhatigan, Fite, & Stuart, 2011), and somatic complaints (Prospero & Kim, 2009), to name a few. In addition, the coping styles victims use may influence the expression of their adjustment difficulties (Straight, Harper, & Arias, 2003). Despite recent evidence that male victims of dating violence often experience similar levels of negative health consequences as their female counterparts (Prospero, 2007), there is considerably less research on male dating violence victimization and adjustment difficulties as compared with female victims. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine the association between male dating violence victimization, PTSD symptoms, relationship satisfaction, and coping styles among heterosexual male college students.

The prevalence of physical and psychological dating aggression victimization among college-age men is surprisingly high. Approximately 20% to 30% of men will be victimized by physical aggression each year and 70% to 90% by psychological aggression (Shorey et al., 2008). Psychological aggression refers to verbal and behavioral acts designed to threaten, intimidate, humiliate, dominate, or control one's partner but do not include physical aggression (Follingstad, Coyne, & Gambone, 2005). Physical aggression refers to behaviors such as slapping, pushing, shoving, kicking, punching, and using a weapon against one's partner (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Although the majority of dating violence is bidirectional in nature (Cornelius, Shorey, & Beebe, 2010), there is some evidence to suggest that males may be victimized more often by physical and psychological aggression than their female counterparts (Katz, Kuffel, & Coblentz, 2002; Shorey et al., 2008; Shorey, Rhatigan, et al., 2011). Moreover, females often initiate aggression more often than males in relationships (e.g., Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2007). These findings should not be interpreted as a way to discount male perpetrated aggression, as this is a serious problem and is often more severe in nature than female perpetrated aggression (Archer, 2000). Still, research does indicate that male victimization is a prevalent and serious problem that deserves attention.

Male victims of dating violence are at an increased risk for adverse mental health consequences relative to non-victims (Hines & Malley-Morrison, 2001). For instance, physical and psychological victimization are associated with increased PTSD symptoms among male victims (Harned, 2001; Hines, 2007). It should be noted that research demonstrates that many victims of domestic violence have also experienced adverse childhood events, such as childhood abuse, which also may increase risk for PTSD symptoms and future victimization (White & Widom, 2003; Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti, 2003). Still, research has yet to examine whether physical victimization is still associated with PTSD symptoms after controlling for psychological victimization, as research with battered women often shows that physical victimization is not associated with PTSD symptoms when psychological victimization is accounted for (Street & Arias, 2001). In fact, research shows that psychological victimization is often associated with a wealth of negative health outcomes above and beyond the effects of physical victimization (Lawrence, Yoon, Langer, & Ro, 2009; O'Leary, 1999). Therefore, research is needed that examines whether psychological victimization, after controlling for the effects of physical victimization, is associated with PTSD symptoms for male victims.

Additional research has shown that dating violence victimization is associated with reduced relationship satisfaction, although results have not been consistent. For instance, Katz et al. (2002) found that physical victimization was associated with reduced relationship satisfaction for females but not males. Kaura and Lohman (2007) found that dating violence victimization was related with reduced relationship satisfaction for male victims, although this study combined physical and psychological victimization into a single “victimization” variable. Capaldi and Crosby (1997) reported that physical victimization was not associated with relationship satisfaction, but psychological victimization was associated with reduced relationship satisfaction among a sample of high-risk, college-age males. There is a wealth of research demonstrating that dating violence victimization is associated with reduced relationship satisfaction for female victims (e.g., Katz, Moore, & May, 2008), although it would be invalid to generalize findings from female victims to male victims. Clearly, additional research is needed to determine whether both physical and psychological victimization are associated with reduced relationship satisfaction among male victims.

As it is becoming increasingly evident that dating violence victimization is associated with negative outcomes, factors that moderate the relationship between victimization and adjustment has been the focus of recent research attention (e.g., Karua & Lohman, 2007; Shorey, Rhatigan, et al., 2011). A moderating variable influences the direction and/or strength between a predictor variable (e.g., victimization) and a dependent variable (e.g., adjustment; Aiken & West, 1991). One potential factor that may moderate and influence the strength of the association between dating violence victimization and adjustment is coping.

Coping can be conceptualized as “the thoughts and behaviors used to manage the internal and external demands of situations that are appraised as stressful” (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004, p. 745). Empirical research has shown that maladaptive coping responses to stressful situations increase the likelihood that mental health problems will develop, while constructive, problem-focused coping responses reduce the likelihood that stressful life events will lead to mental health problems (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Problem-focused coping involves addressing stressful situations, which can include concentrating on what to do next, making a plan for action, and seeking help from other people, and is considered to be an adaptive form of coping (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). On the other hand, emotion-focused coping, which involves cognitive and behavioral attempts to avoid the problem either through self-blame, denial, wishful thinking, or distraction (Taylor & Stanton, 2007; Vitaliano, Russo, Carr, Maiuro, & Becker, 1985), is generally a maladaptive coping style and is associated with increased mental health problems (Taylor & Stanton, 2007).

Research that has examined the role of coping among victims of domestic violence has supported the moderating role of coping on the association between victimization and PTSD symptoms. For instance, Lilly and Graham-Bermann (2010) reported that emotion-focused coping moderated the association between physical victimization and PTSD symptoms among female domestic violence shelter residents, such that women low on emotion-focused coping had less PTSD symptoms. In addition, Straight et al. (2003) reported that approach coping, which is similar to problem-focused coping, moderated and reduced the association between psychological aggression victimization from a dating partner and health complaints among female college students. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that female victims of violence often use more maladaptive coping responses (e.g., emotion-focused coping) than nonvictims (Coffey, Leitenberg, Henning, Bennett, & Jankowski, 1996). In all, research supports problem-focused coping as an adaptive coping style and emotion-focused coping as a maladaptive coping style among female victims of domestic and dating violence.

Unfortunately, we are unaware of research that has examined the moderating role of coping among male victims of dating violence and how coping may affect relationship satisfaction among victims. Because research suggests that males and females often employ different coping responses during times of stress (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002), it would be invalid to generalize findings from female victims to male victims. For instance, females are more likely to cope by seeking the help of other people and by using positive self-talk statements (Tamres et al., 2002), coping responses that fall under problem-focused coping. It is additionally invalid to generalize findings from battered women studies to male victims of dating violence, as battered women experience more frequent and severe abuse and have greater rates of PTSD than many male and female victims of dating violence in college samples. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine the association between psychological and physical dating violence victimization, PTSD symptoms, relationship satisfaction, and coping (problem focused and emotion focused) among males. On the basis of previous research and theories of coping, the following were hypothesized:

Both psychological and physical victimization would be positively associated with PTSD symptoms and negatively associated with relationship satisfaction.

The association between psychological and physical victimization and adjustment (PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction) would be moderated by problem-focused coping, with problem-focused coping reducing the strength of the association between victimization and adjustment.

The association between psychological and physical victimization and adjustment would be moderated by emotion-focused coping, with emotion-focused coping increasing the strength of the association between victimization and adjustment.

Method

Participants

A total of 187 male students from Introduction to Psychology courses at a large southeastern university participated in the current study. Students who were in a 1 month or longer dating relationship and were 18 years of age or older were eligible for participation. The majority of participants were heterosexual (98.4%; n = 184). Thus, only heterosexual males were included. The majority of participants were not currently living with their dating partner (92.9%; n = 171). The ethnic composition of participants included 87% (n = 163) non-Hispanic White, 8.2% (n = 15) African American, 1.6% (n = 3) Asian, and 3.2% (n = 6) identified as “other” (e.g., Hispanic, Middle Eastern, etc.). Academically, 63% (n = 116) were freshmen, 23.4% (n = 43) were sophomores, 10.3% (n = 19) were juniors, 2.7% (n = 5) were seniors, and 0.5% (n = 1) were postgraduates. The mean age of participants was 19.41 years (SD = 1.62), and the average length of participant's current dating relationship was 10.35 months (SD = 11.52). The students in the current study also participated in research that has been reported elsewhere (Shorey, Rhatigan, et al., 2011).

Procedures

Students completed all measures through an online survey website that uses encryption to ensure confidentiality of responses. Prior to completing the measures of interest for the current study, students completed an informed consent, which was also provided online. After obtaining consent, the measures were presented with standardized instructions. After students completed all measures, a list of local referrals for dating violence was provided.

Materials

Demographic questionnaire

Participants were asked to specify their age, ethnicity, academic status, sexual orientation, whether they were currently living with their dating partner, and length of their current dating relationship.

Dating violence

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) was used to examine physical dating violence victimization. The CTS2 contains 78 items, 12 of which examine physical victimization. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency, in the past 6 months, of their physical victimization (0 = never; 6 = more than 20 times). An example item is “My partner pushed or shoved me.” A total score for the physical victimization subscale was obtained by summing the frequency of each behavior, with scores for each item ranging from 0 to 25 (Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). The CTS2 is one of the most widely used measures of dating violence victimization and has demonstrated good internal consistency in male and female college students (Straus et al., 1996). Internal consistency for the current study was .72, which is consistent with the majority of research on the physical aggression subscale of the CTS2 (e.g., Ro & Lawrence, 2007).

Psychological victimization was assessed using the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory–Short Version (PMWI-Short; Tolman, 1989). The PMWI contains 14 items in which respondents indicate their experience with psychological victimization using a 5-point scale (1 = never; 5 = very frequently). An example item is “My partner yelled and screamed at me.” The PMWI has separate versions to use with male and female participants. Scores on the PMWI can range from 14 to 70. The PMWI has shown good internal consistency and validity in male and female college students (e.g., Straight et al., 2003; Tolman, 1989). Internal consistency of the PMWI in the current study was .91.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) was used to examine posttraumatic stress symptoms. The PCL is a 17-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms consistent with the diagnostic criteria of PTSD as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The PCL asks participants to rate the extent to which they have been bothered by PTSD symptoms in the past month (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely). Symptoms assessed by the PCL include reexperiencing symptoms, avoidance of memories, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal. An example item is “How bothered have you been by feeling emotionally numb or being unable to have loving feelings for those close to you?” Research has supported the internal consistency (e.g., α = .90) and validity of the PCL with college students (Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003; Taft, Schumm, Orazem, Meis, & Pinto, 2010). Internal consistency of the PCL for the current study was .94.

Relationship satisfaction

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988) was used to examine participants’ relationship satisfaction with their current dating partner. The RAS contains 7 items that are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = poorly; 5 = very good). An example item is “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?” Higher scores on the RAS correspond to greater relationship satisfaction. The RAS is a widely used measure of relationship satisfaction and has been shown to be highly correlated with the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Hendrick, Dicke, & Hendrick, 1998). The internal consistency and reliability of the RAS has been reported to be good in male and female college students (α = .86; Hendrick et al., 1998). The internal consistency of the RAS for the current study was .90.

Coping styles

The Ways of Coping Checklist–Revised Version (WCCL; Vitaliano et al., 1985) was used to examine participants’ coping styles. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they have used each coping style in response to stressful situations (0 = not use; 3 = use a great deal). The WCCL contains five subscales: problem-focused, seeking social support, avoidant, wishful thinking, and blamed-self. Consistent with previous research (Parker & Lee, 2007; Rudnick, 2001), the problem-focused and seeking social support subscales were combined into an overall Problem-Focused Coping indicator, whereas the avoidant, wishful thinking, and blamed-self subscales were combined into an overall Emotion-Focused Coping indicator.1 An example item for problem-focused coping is “Talked to someone who could do something about the problem” and an example item for emotion-focused coping is “Wished I could change the way I felt.” The WCCL has demonstrated good reliability (e.g., α = .74 to .88) in college students (Vitaliano et al., 1985). For the current study, internal consistencies were .90 for problem focused and .92 for emotion focused.

Data Analytic Strategy

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test possible moderating effects of coping styles (problem-focused and emotion-focused) on the association between psychological and physical dating violence victimization and PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction. Kline (2005) suggests a sample size of 100 or greater is needed for SEM analyses, and our sample size of 187 exceeded this recommended sample size. AMOS version 17.0 was employed for analyses. All models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIMLE), which uses all data to estimate parameters and does not exclude observations with missing data (Kline, 2005). Compared with pairwise and listwise deletion, FIMLE has been shown to be less biased and more efficient for handling missing data (Arbuckle, 1996). Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The chi-square fit index assesses the discrepancy between the sample and the fitted covariance matrices. The chi-square fit index is estimated by dividing the chi-square estimate by the degrees of freedom, with values <2.0 indicative of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The CFI compares the estimated model's fit to that of the “independence,” or null, model, with values of .95 or higher indicative of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Finally, the RMSEA is an indicator of model error per degrees of freedom, with values <.06 indicative of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Relative to other model fit indices, the CFI and RMSEA have greater ability to identify misspecified models and are commonly used (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

A common approach for evaluating moderation within an SEM framework is through multiple group modeling (Kline, 2005). This approach requires grouping individuals based on levels of a moderator. However, dichotomizing continuous variables to create groups, as is the case with the current moderators (i.e., coping), reduces power (Cohen, 1983; MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). For that reason, it is recommended to evaluate continuous moderators by adding interactions to the path model (Kline, 2010; Tomarken & Waller, 2005). Thus, for the current analyses, the addition of interaction terms was chosen over a multiple group approach.

Consistent with the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991) for examining moderation, predictor variables (i.e., aggression), moderators (i.e., coping styles), and the control variable (i.e., relationship length) were mean centered to aid in the interpretation of moderated effects and to reduce multicollinearity among variables. Relationship length was controlled for due to research reporting a positive association between relationship length and relationship satisfaction (Marcus & Swett, 2002). After all variables were mean centered, three steps were used to examine potential interactions. The first step involved examining the main effects of the predictor variables and control variable on the dependent variables (i.e., PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction), which were estimated to establish the association between variables (Aiken & West, 1991). The second step involved adding two-way interaction terms to the model, one at a time. Interaction terms were computed by multiplying the centered scores of the predictor variables with the moderating variables. Finally, if significant interactions were identified, predictor variables were probed at high (+1 SD) and low (–1 SD) levels of the moderator (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Psychological and physical victimization were positively associated with PTSD symptoms and negatively associated with relationship satisfaction. Psychological victimization and PTSD symptoms were positively associated with emotion-focused coping, whereas relationship satisfaction was negatively associated with emotion-focused coping. In addition, relationship satisfaction was positively associated with problem-focused coping. The mean levels of physical and psychological victimization are consistent with previous research on male dating violence victimization (e.g., Simonelli & Ingram, 1998).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological victimization | — | 57*** | .34*** | –.50*** | –.09 | .14* | .19** |

| 2. Physical victimization | — | .26*** | –31*** | –.12 | .10 | .01 | |

| 3. PTSD symptoms | — | –.35*** | .03 | .42*** | –.01 | ||

| 4. Relationship satisfaction | — | .24** | -.20** | .04 | |||

| 5. Problem-focused coping | — | .19** | .06 | ||||

| 6. Emotion-focused coping | — | –.01 | |||||

| 7. Relationship length | |||||||

| Mean | 7.16 | 3.69 | 28.54 | 28.44 | 32.92 | 25.46 | 10.35 |

| Standard deviation | 8.07 | 10.51 | 11.71 | 5.70 | 9.74 | 11.05 | 11.52 |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In addition, the prevalence of psychological aggression victimization was 82.1% and physical aggression victimization was 36.4%, rates consistent with previous research on male victims of dating violence (Shorey et al., 2008). T tests showed that victims of physical violence had more symptoms of PTSD (M = 32.72, SD = 12.50) than nonvictims (M = 26.15, SD = 10.56), t(182) = 3.79, p < .001, and victims had lower relationship satisfaction (M = 26.69, SD = 5.72) than nonvictims (M = 29.44, SD = 5.46), t(182) = 3.23, p < .01. Victims of psychological aggression reported more symptoms of PTSD (M = 29.79, SD = 12.11) than nonvictims (M = 22.83, SD = 7.42), t(182) = 3.17, p < .01, lower relationship satisfaction (M = 28.03, SD = 5.67) than nonvictims (M = 30.33, SD = 5.52), t(182) = 2.11, p < .05, and less problem-focused coping (M = 32.10, SD = 9.28) than nonvictims (M = 36.78, SD = 10.95), t(182) = 2.53, p < .05. There were no other significant differences between victims and nonvictims on any of the variables examined in the current study or on any demographic variables.

Moderation

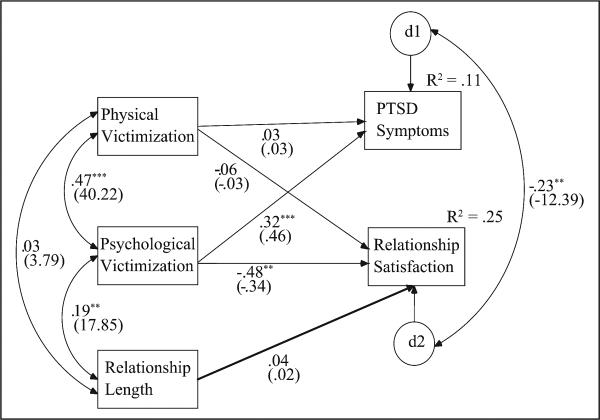

The first step involved evaluating the associations of the predictor variables (victimization) on the dependent variables (PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction), while controlling for relationship length. As displayed in Figure 1, this model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(1) = 1.20, p = .27, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03. Psychological victimization was significantly associated with increased PTSD symptoms and decreased relationship satisfaction. Physical victimization was unrelated to PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction. Having established the model fit and associations among predictor variables, the next step involved examining the moderating effect of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping.

Figure 1. Main effects model of predictor variables.

Note. χ2(1) = 1.20, p = .27, comparative fit index = .99, root mean squared error of approximation = .03. R2 = amount of variance predicting relationship satisfaction and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, respectively. Numbers outside parentheses are standardized and numbers inside parentheses are unstandardized.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Problem-Focused Coping

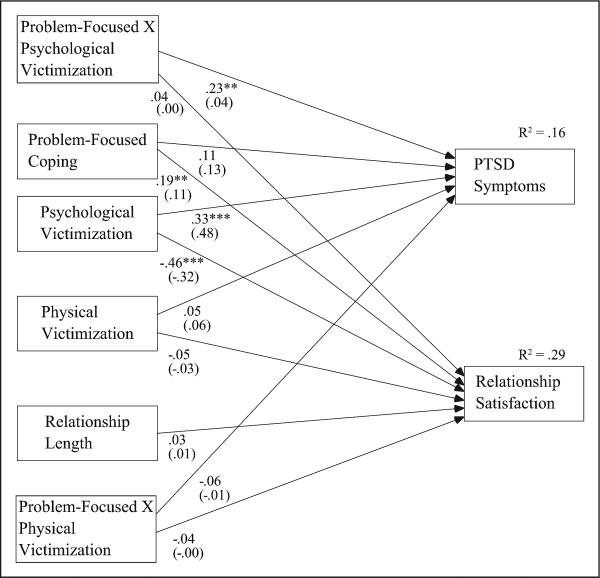

The main effect of problem-focused coping and interaction terms between problem-focused coping and victimization were added to the model. As displayed in Figure 2, this model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(1) = .87, p = .35, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .00. The interaction term of problem-focused coping and psychological victimization was significantly associated with PTSD symptoms (β = .04, p < .01). No other interactions were related to PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction. Thus, the problem-focused coping and psychological victimization interaction was probed at high and low levels of coping. At high levels of problem-focused coping, psychological victimization was associated with increased PTSD symptoms (β = .61, p < .001). At low levels of problem-focused coping, psychological victimization was no longer associated with PTSD symptoms (β = .07, p > .05).

Figure 2. Problem-focused coping interaction model.

Note. χ2(1) = .87, p = .35, comparative fit index = 1.0, root mean squared error of approximation = .00. R2 = amount of variance predicting relationship satisfaction and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, respectively. Numbers outside parentheses are standardized and numbers inside parentheses are unstandardized. Covariances are not presented for clarity purposes.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Emotion-Focused Coping

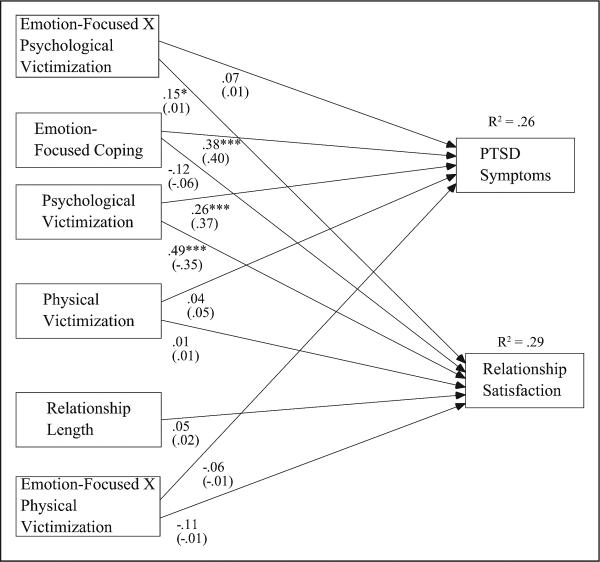

The main effect of emotion-focused coping and interaction terms between emotion-focused coping and victimization were added to the model. As displayed in Figure 3, this model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(1) = .60, p = .36, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .00. The interaction term of emotion-focused coping and psychological victimization was significantly associated with relationship satisfaction (β = .15, p < .05). No other interactions were related to PTSD symptoms or relationship satisfaction. Thus, the emotion-focused coping and psychological victimization interaction was probed at high and low levels of coping. At high levels of emotion-focused coping, psychological victimization was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (β = –.32, p < .01). At low levels of emotion-focused coping, psychological victimization was also negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (β = –.66, p < .001). Although psychological victimization was associated with decreased relationship satisfaction at both high and low levels of emotion-focused coping, the magnitude of this association was stronger at low levels of emotion-focused coping.

Figure 3. Problem-focused coping interaction model.

Note. χ2(1) = .80, p = .36, comparative fit index = 1.0, root mean squared error of approximation = .00. R2 = amount of variance predicting relationship satisfaction and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, respectively. Numbers outside parentheses are standardized and numbers inside parentheses are unstandardized. Covariances are not presented for clarity purposes

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the associations between physical and psychological dating violence victimization and PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction among a sample of college men. To our knowledge this was the first study to examine whether problem-focused and emotion-focused coping moderated the association between victimization and adjustment among male victims of dating violence. Findings from the current study showed a number of interesting results that have important implications for future research and dating violence intervention programs.

Our findings indicated that the rates of psychological and physical victimization were very high, consistent with previous research on dating violence (Shorey et al., 2008). In addition, the prevalence of these forms of aggression was as high, if not higher, than those found in community samples of men, particularly for physical victimization (e.g., Hines & Douglas, 2011). Results of the bivariate correlation analyses indicated that both physical and psychological victimization were associated with increased PTSD symptoms and decreased relationship satisfaction. However, results from the path model indicated that only psychological victimization remained significantly associated with PTSD symptoms and relationship satisfaction when both types of victimization were examined simultaneously. This is consistent with research that reports that psychological victimization can be more detrimental to victims’ adjustment than physical aggression victimization (Lawrence et al., 2009; O'Leary, 1999). This is also the first known study to find psychological victimization to be associated with PTSD symptoms above and beyond the effects of physical victimization for male victims of dating violence. This finding parallels research with female victims (Street & Arias, 2001). Together, these results indicate that psychological aggression is a construct that deserves attention in intervention and treatment programs for male victims.

Results of the moderation analyses did not support the proposed hypotheses. Problem-focused coping did not moderate and reduce the association between victimization and adjustment. Rather, at high levels of problem-focused coping, psychological victimization was associated with increased PTSD symptoms, not decreased PTSD as would be proposed by theory. Because this is the first known study to examine the moderating effect of problem-focused coping on the association between psychological victimization and PTSD symptoms, these findings should be considered preliminary until replicated. Still, it is surprising that this association was opposite of what was expected. However, this theoretically counterintuitive finding may be because of the nature of psychological aggression.

Psychological aggression is often intended to attack victims’ sense of self-worth, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (Follingstad, 2009; Murphy & Hoover, 1999). If victims come to internalize the psychologically abusive messages levied on them by their intimate partners then it is possible that they would have decreased self-efficacy. Indeed, research reports that psychological aggression victimization is associated with decreased self-efficacy (Raghavan, Swan, Snow, & Mazure, 2005). Theoretically, this decreased self-efficacy could, in turn, make it difficult for victims to believe that they have the ability to engage in problem-focused coping responses and subsequently make the problem better. Thus, it may be that the more problem-focused coping in which a victim of psychological aggression engages, the more evidence they gather that they are incapable of solving the problem, thus leading to reduced self-efficacy. The futility of trying to resolve the problem in an active manner could, in turn, increase symptoms of PTSD. Alternatively, because male victims of dating violence rarely seek help for their victimization experiences (Cornelius, Shorey, & Kunde, 2009), it is possible that the victims with more severe PTSD symptoms were higher on problem-focused coping (which included seeking social support) because of an increased need for help due to their PTSD symptoms. Thus, research is needed to determine whether self-efficacy affects the association between psychological victimization, PTSD symptoms, and problem-focused coping.

Another potential explanation for this finding may be gleaned from male gender role norms. That is, men are generally socialized to be assertive, maintain control in their relationships, and avoid expressing emotions (Pleck, 1995). However, when these gender role norms are not being upheld, significant stress and anxiety is produced (Eisler, 1995). With respect to the current study, psychological aggression may undermine male victims’ sense of masculinity since they may believe that they have failed to maintain control in their relationship. This reduced sense of masculinity could be exacerbated when male victims attempt to focus on their problems and seek help for them, which likely involves expressing emotions and falls under the category of problem-focused coping. In turn, this may result in a spike in mental health symptoms. Thus, future research would benefit from examining how masculinity and gender roles may fit into the coping responses of male victims of dating violence.

The results of moderation analyses examining emotion-focused coping also showed an interesting finding for psychological aggression specifically. That is, at high levels of emotion-focused coping, the association between psychological victimization and relationship satisfaction was weaker (although still negative) than at low levels of emotion-focused coping. Again, it is possible that this finding may be affected by reduced self-efficacy. Research indicates that psychological aggression victimization is associated with reduced relationship self-efficacy, the belief that one is capable of handling problems in their relationship successfully (Raghavan et al., 2005). Thus, the more one is aware of the problems in his relationship, which is in turn associated with less emotion-focused coping (i.e., less avoidance of the problem), then it is possible that one would then report less relationship satisfaction. This relationship could be made worse if the individual does not believe they have the capabilities to handle their relationship problems (i.e., reduced relationship self-efficacy), which could be caused by psychological aggression and exacerbated when one is not avoiding the stress in their relationship (i.e., low emotion-focused coping). As with the findings for problem-focused coping, additional research is needed to replicate this finding and determine how relationship specific self-efficacy may affect the association between psychological victimization, relationship satisfaction, and emotion-focused coping. It is also possible that this finding is because of victims’ perpetration of aggression. That is, if both partners perpetrate psychological aggression, it is possible that partners feel validated, as both are likely sharing negative thoughts and emotions. Future research would benefit from examining how perpetration affects the relations among victimization, relationship satisfaction, and coping.

Although preliminary, results from the current study may have important implications for individuals who work with male victims of dating violence. First, findings suggest that psychological victimization should be given attention, even when physical aggression is present. Indeed, researchers and individuals who work with dating violence victims have advocated for dating violence prevention programs to focus on psychological aggression (Shorey, Meltzer, & Cornelius, 2010). Second, findings suggest that careful consideration should be given to how each victim's coping styles are affecting them. Tailored interventions may help determine the coping style each victim uses, how they are helpful or harmful, and what coping skills could be taught to victims that will provide them with the most beneficial outcomes.

There are a number of limitations from the current study that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the cross-sectional design prohibits the determination of causality among study variables. Longitudinal research is needed to disentangle the relationship between victimization, coping, PTSD, and relationship discord. The reliance on self-report measures is also problematic. Although our use of the PCL is consistent with the majority of research on PTSD symptoms in victims of dating/domestic violence in that it assessed trauma symptoms not necessarily caused by victimization experiences (e.g., Arias & Pape, 1999; Harned, 2001; Hines, 2007; Street & Arais, 2001), semistructured interviews, such as the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (Blake et al., 1995), could provide more accurate reports of and whether PTSD symptoms are in response to victimization experiences. In addition, the measure of coping asked participants to report on their general coping responses to stress, not their coping in response to victimization experiences, PTSD symptoms, or relationship problems. Although this is consistent with the majority of research on victimization and coping (e.g., Lilly & Graham-Bermann, 2010; Straight et al., 2003), future research would benefit from asking participants about their coping responses to victimization experiences specifically, although we are unaware of any standardized self-report measures designed specifically for examining coping responses to victimization experiences. The relatively low rate of PTSD symptoms in this sample also represents a limitation, and this may have affected the results obtained by having a restricted range of PCL scores. In addition, the CTS2 and PMWI do not take into account the context that surrounds aggression victimization, which may be particularly important when examining male dating violence victimization. The use of a college student sample of primarily non-Hispanic Caucasian males limits the generalizability of these findings to more diverse populations. Future research should also compare the experiences of males who are victimized in both heterosexual and homosexual relationships.

In summary, the current study adds to the growing body of literature on male dating violence victimization and mental health and relationship outcomes. Findings indicated that psychological aggression was associated with increased PTSD symptoms and decreased relationship satisfaction above and beyond the effects of physical victimization. In addition, results showed an interesting pattern of findings when coping was examined as a moderator of the relationships between victimization and adjustment. These findings suggest that the coping responses male victims of dating violence use will be an important area of investigation for future research. Future research should also consider examining the gender symmetry of dating violence when examining male victims and negative outcomes. That is, taking into consideration victims’ perpetration may be an important factor in determining the relations among victimization, coping, and negative outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

We considered forming problem-focused and emotion-focused coping variables as latent constructs. However, because the problem-focused coping variable only contained two indicators there were identification problems, which can occur when latent variables contain too few indicators (Kline, 2005). Accordingly, latent constructs were not created for coping.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Shumaker RE, editors. Advances structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, Pape KT. Psychological abuse: Implications for adjustment and commitment to leave violent partners. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. doi:10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00101.x. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey P, Leitenberg H, Henning K, Bennett RT, Jankowski MK. Dating violence: The association between methods of coping and women's psychological adjustment. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. The cost of dichotomization. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1983;7:249–253. doi:10.1177/014662168300700301. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius TL, Shorey RC, Beebe SM. Self-reported communication variables and dating violence: Using Gottman's marital communication conceptualization. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:439–448. doi:10.1007/s10896-010-9305-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius TL, Shorey RC, Kunde A. Legal consequences of dating violence: A critical review and directions for improved behavioral contingencies. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:194–204. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM. The relationship between masculine gender role stress and men's health risk: The validation of a construct. In: Levant R, Pollack W, editors. The new psychology of men. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR. The impact of psychological aggression on women's mental health and behavior: The status of the field. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:271–289. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334453. doi:10.1177/1524838009334453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Coyne S, Gambone L. A representative measure of psychological aggression and its severity. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS. Abused women or abused men? An examination of the context and outcomes of dating violence. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:269–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:93–98. doi:10.2307/352430. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS, Dicke A, Hendrick C. The Relationship Assessment Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:137–142. doi:10.1177/0265407598151009. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among men who sustain partner violence: An international multisite study of university students. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2007;8:225–239. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.8.4.225. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Douglas EM. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in men who sustain intimate partner violence: A study of helpseeking and community samples. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2011;12:112–127. doi: 10.1037/a0022983. doi:10.1037/a0022983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Malley-Morrison K. Psychological effects of partner abuse against men: A neglected research area. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2001;2:75–85. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.2.2.75. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Kuffel SW, Coblentz A. Are there gender differences in sustaining dating violence? An examination of frequency, severity, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17:247–271. doi:10.1023/A:1016005312091. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Moore J, May P. Physical and sexual covictimization from dating partners: A distinct type of intimate abuse? Violence Against Women. 2008;14:961–980. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320905. doi:10.1177/1077801208320905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, Lohman BJ. Dating violence victimization, relationship satisfaction, mental health problems, and acceptability of violence: A comparison of men and women. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:367–381. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9092-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, Ro E. Is psychological aggression as detrimental that physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MM, Graham-Bermann SA. Intimate partner violence and PTSD: The moderating role of emotion-focused coping. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:604–616. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.604. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF, Swett B. Violence and intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:570–586. doi:10.1177/0886260502017005006. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Hoover SA. Measuring emotional abuse in dating relationships as a multifactorial construct. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD. Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:3–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Lee C. Relationships among abuse characteristics, coping strategies, and abuse women's psychological health: A path model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:1184–1198. doi: 10.1177/0886260507303732. doi:10.1177/0886260507303732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In: Levant R, Pollack W, editors. The new psychology of men. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Prospero M. Mental health symptoms among male victims or partner violence. American Journal of Men's Health. 2007;1:269–277. doi: 10.1177/1557988306297794. doi:10.1177/1557988306297794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospero M, Kim M. Mutual partner violence: Mental health symptoms among female and male victims in four racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:2039–2056. doi: 10.1177/0886260508327705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan C, Swan SC, Snow DL, Mazure CM. The mediational role of relationship efficacy and resource utilization in the link between physical and psychological abuse and relationship termination. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:65–88. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271514. doi:10.1177/1077801204271514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro E, Lawrence E. Comparing three measures of psychological aggression: Psychometric properties and differentiation from negative communication. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:575–586. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9109-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick A. The impact of coping on the relation between symptoms and quality of life. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2001;64:304–308. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.4.304.18599. doi:10.1521/psyc.64.4.304.18599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist–Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. doi:10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Meltzer C, Cornelius TL. Motivations for self-defensive aggression in dating relationships. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:662–676. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.662. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Rhatigan DL, Fite PJ, Stuart GL. Dating violence victimization and alcohol problems: An examination of the stress-buffering hypothesis for perceived support. Partner Abuse. 2011;2:31–45. doi:10.1891/1946–6560.2.1.31. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Sherman AE, Kivisto AJ, Elkins SR, Rhatigan DL, Moore TM. Gender differences in depression and anxiety among victims of intimate partner violence: The moderating effect of shame-proneness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:1834–1850. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli CJ, Ingram KM. Psychological distress among men experiencing physical and emotional abuse in heterosexual dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Straight ES, Harper FWK, Arias I. The impact of partner psychological abuse on health behaviors and health status in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:1035–1054. doi: 10.1177/0886260503254512. doi:10.1177/0886260503254512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactic Scales handbook. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, Arias I. Psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in battered women: Examining the roles of shame and guilt. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:65–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight ES, Harper FWK, Arias I. The impact of partner psychological abuse on health behaviors and health status in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:1035–1054. doi: 10.1177/0886260503254512. doi:10.1177/0886260503254512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm J, Orazem RJ, Meis L, Pinto LA. Examining the link between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and dating aggression perpetration. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:456–469. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and examination of relevant coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:2–30. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Stanton AL. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims. 1989;4:159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Carr JE, Maiuro RD, Becker J. The ways of coping checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1985;20:3–26. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2001_1. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility.. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; Chicago. Nov, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Widom CS. Intimate partner violence among abused and neglected children in young adulthood: The mediating effects of early aggression, antisocial personality, hostility, and alcohol problems. Aggressive Behaviors. 2003;29:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield CL, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ. Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:166–185. [Google Scholar]