In lung macrophages, inhibition of p40phox by PGE2 represents a brake on bacterial killing, and likely contributes to impaired lung innate immunity.

Keywords: immunosuppression, prostaglandins, protein kinase A, Akt1, lung, Fc receptors

Abstract

PGE2, produced in the lung during infection with microbes such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, inhibits alveolar macrophage (AM) antimicrobial functions by preventing H2O2 production by NADPH oxidase (NADPHox). Activation of the NADPHox complex is poorly understood in AMs, although in neutrophils it is known to be mediated by kinases including PI3K/Akt, protein kinase C (PKC) δ, p21-activated protein kinase (PAK), casein kinase 2 (CK2), and MAPKs. The p40phox cytosolic subunit of NADPHox has been recently recognized to function as a carrier protein for other subunits and a positive regulator of oxidase activation, a role previously considered unique to another subunit, p47phox. The regulation of p40phox remains poorly understood, and the effect of PGE2 on its activation is completely undefined. We addressed these issues in rat AMs activated with IgG-opsonized K. pneumoniae. The kinetics of kinase activation and the consequences of kinase inhibition and silencing revealed a critical role for a PKCδ-PAK-class I PI3K/Akt1 cascade in the regulation of p40phox activation upon bacterial challenge in AMs; PKCα, ERK, and CK2 were not involved. PGE2 inhibited the activation of p40phox, and its effects were mediated by protein kinase A type II, were independent of interactions with anchoring proteins, and were directed at the distal class I PI3K/Akt1 activation step. Defining the kinases that control AM p40phox activation and that are the targets for inhibition by PGE2 provides new insights into immunoregulation in the infected lung.

Introduction

Pneumonia is the leading cause of infectious death in the United States [1], and World Health Organization data indicate that respiratory infections have a greater global impact than any other category of disease [2]. Resistance to antimicrobial agents is a major challenge in the treatment of pneumonia, exemplified by the emergence of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae [3]. A better understanding of host innate immune defenses against pneumonia-causing pathogens is an important step in developing novel preventive and therapeutic strategies. Alveolar macrophages (AMs) are the resident innate immune cells of the distal lung [4]. One pivotal means by which they eliminate microbes is the generation of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROIs) [5, 6], primarily via the actions of the phagocyte oxidase NADPH oxidase (NADPHox).

NADPHox [7] is a multisubunit complex comprising 1) a catalytic core consisting of gp91phox and p22phox (cytochrome b558), localized at the membrane, along with the regulator Rap1a, a Ras-related GTP-binding protein, and 2) cytosolic subunits p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox and a small GTP-binding protein, either Rac1 or Rac2. Moreover, peroxiredoxin 6, a dual-function enzyme that includes a phospholipase A2 activity, has been recently shown to facilitate the assembly and the activation of the oxidase complex [8]. NADPHox activation requires the phosphorylation of cytosolic subunits, which results in their recruitment to the catalytic core at the membrane [9]. The classic paradigm for NADPHox activation recognized p47phox as the primary initiator of cytosolic subunit translocation responsible for carrying p40phox and p67phox subunits to the membrane [10–14]. However, recent studies have revealed an essential role for p40phox in NADPHox activation [15–19]. It has been acknowledged that p40phox has an independent carrier role, and both p47phox and p40phox are now thought to be required for full and stable activation of NADPHox [20–22].

The activation of NADPHox stimulated by ligation of the opsonic Fcγ receptor (FcγR) for IgG has been well studied in neutrophils. In this model, numerous kinases have been demonstrated to mediate cytosolic subunit phosphorylation, including PI3K and its downstream partner Akt, protein kinase C (PKC) δ, p21-activated protein kinase (PAK), casein kinase 2 (CK2), and ERK, and p38 forms of MAPKs [12, 22–24]. The activation of each of these kinases is controlled by its own phosphorylation level and can be opposed by a variety of phosphatases. Despite their importance in pulmonary antimicrobial defense, much less is known about NADPHox activation in primary AMs than in either peripheral blood neutrophils or macrophage cell lines.

During infection of the distal lung and other sites, PGE2, a bioactive lipid mediator derived from the cyclooxygenase metabolism of arachidonic acid, is generated in large quantities by both macrophages and neighboring epithelial cells [25–27]. Although PGE2 is often viewed as a pro-inflammatory mediator, its effects on phagocytes are largely suppressive and include inhibition of FcγR-mediated microbial killing and NADPHox activity [28]. These suppressive actions may help to promote resolution of tissue inflammation once infection has been contained, but enhanced production of PGE2 could impair innate immunity. Indeed, excessive generation of PGE2 has been implicated in immunosuppressive states including bone marrow transplantation [29–31], cancer [32], aging [33], malnutrition [34], and cystic fibrosis [35]. These suppressive actions on macrophages, including AMs, are mediated by ligation of E prostanoid (EP) receptors 2 and 4, which are coupled to a stimulatory G protein α-subunit that activates adenylyl cyclase to catalyze the formation of cAMP [36–39]. The main target of this second messenger is the effector protein kinase A (PKA), a holoenzyme composed of two catalytic (C) subunits that are held in an inactive conformation by a dimer of regulatory (R) subunits of either RI or RII type [40]. The holoenzyme is activated when cAMP binds to the R subunits, releasing the active C subunits [40]. A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) are a family of large scaffold proteins that can organize and localize PKA and its signaling partners at specific subcellular sites [40].

In view of the recently recognized importance of p40phox in the regulation of NADPHox and the paucity of knowledge regarding its regulation, the first goal of this study was to characterize the kinase network responsible for FcγR-mediated activation of p40phox in AMs. This information then provided a framework for determining the regulatory events targeted by PGE2 to effect inhibition of FcγR-mediated p40phox activation. We used AM challenged with IgG-opsonized K. pneumoniae, because 1) this represents a biologically relevant stimulus, 2) the FcγR signaling pathway has been extensively characterized in neutrophils, and 3) we have previously observed inhibition of this process by PGE2 in AMs [28]. This work provides new mechanistic insights and may reveal new opportunities to therapeutically manipulate innate immune defense of the lung.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Pathogen-free 125- to 150-g female Wistar rats from Charles River Laboratories (Portage, MI, USA) were used. Animals were treated according to NIH guidelines for the use of experimental animals with the approval of the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals.

Reagents

RPMI 1640 was purchased from Gibco-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Protein A-Sepharose beads were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA). PGE2 from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was dissolved in DMSO and stored under N2 at −80°C. Rabbit polyclonal Abs against phospho-p40phox (Thr154), p40phox, p47phox, phospho-PKCδ (Thr507), and PKCδ, as well as mouse polyclonal Ab against PAK, were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse polyclonal anti-gp-91phox was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Mouse polyclonal Abs against phospho-Akt (Ser473) and phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), and rabbit polyclonal Abs against Akt, Akt1, phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-PAK1 (Thr423)/PAK2 (Thr402), and ERK were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Mouse monoclonal Ab against β-actin was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PKA-RII-selective activator N6-mono-t-butylcarbamoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (6-MBC-cAMP), PKA RI-selective inhibitor 8-chloroadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer (Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS) and PKA RII-selective inhibitor 8-piperidinoadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer (Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS) were purchased from Biolog Life Science Institute (Howard, CA, USA). The PKA-RII/AKAP disruptor peptide Ht31, and its corresponding control peptide Ht31P, were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Kinase inhibitors rottlerin (PKCδ), LY29004 (PI3K), PAK18 (PAK), Akti-VIII (Akt), Ro-32-0432 (PKCα), U0126 (ERK1/2), SB203580 (p38 MAPK), phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK) 1 inhibitor II (PDK1), bpV(bipy) [phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN)], and 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBB) and (E)-3-(2,3,4,5-tetrabromophenyl)acrylic acid (TBCA) (CK2) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Specific class I PI3K inhibitors IC87114 (p110δ catalytic subunit) and GDC-0941 (p110α catalytic subunit) were obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). AS605240 (p110γ catalytic subunit) and TGX-221 (p110β catalytic subunit) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. Compounds requiring reconstitution were dissolved in either PBS or DMSO. Required dilutions of all compounds were prepared immediately before use, and equivalent quantities of vehicle were added to the appropriate controls. DMSO at the concentrations used (0.0001–1%) had no direct effect on H2O2 generation.

Cell isolation and culture

Resident AMs from rats were obtained by lung lavage, as described previously [28] and were resuspended in RPMI 1640 to a final concentration of 1–3 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were allowed to adhere to tissue culture-treated plates for 1 h (37°C, 5% CO2), resulting in >99% of adherent cells identified as macrophages by use of modified Wright-Giemsa stain (Diff-Quick) from American Scientific Products (McGraw Park, IL, USA). Cells were cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 containing 5% FBS. The following day, medium was removed to remove nonadherent cells and replaced by PBS for treatment. For Amplex UltraRed experiments, RPMI 1640 without phenol red was used.

Cell treatments

AMs were pretreated with or without kinase inhibitors for 30 min and with or without PGE2 or cAMP analog for 10 min and then were challenged with IgG-opsonized K. pneumoniae (IgG-K. pneumoniae) [multiple of infection (MOI) 50:1] for time intervals ranging from 1 to 15 min (Western blot for kinase phosphorylation) or 60 min (Amplex UltraRed for H2O2 production). Immune serum, source of the bacteria, and method for opsonization were as described previously [41]. For some Amplex experiments, cells were also treated with 50:1 unopsonized K. pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae).

H2O2 detection

AMs were plated in 96-well dishes at 5 × 105 cells/well. To determine H2O2 secretion from AMs, we adapted our previous colorimetric assay [28] to the fluorimetric assay using the Amplex UltraRed reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions with some modifications. In brief, AMs were incubated for 1 h directly with 50 μl of PBS containing 200 μM Amplex UltraRed reagent and 20 U/ml HRP in the presence or absence of IgG-K. pneumoniae. To assess the effects of kinase activation and PGE2 signaling on H2O2 production, AMs were pretreated with compounds as described above before challenge with IgG-K. pneumoniae. For some Amplex experiments, cells were also treated with unopsonized K. pneumoniae. Values from a given condition in each independent experiment were taken as the mean of 5 replicates. The stimulated increment in H2O2 was calculated by subtracting the mean value of 5 untreated replicates from the raw value for each of the 5 replicates corresponding to a single condition. Data were expressed as a percentage of the stimulated increment in H2O2 or as indicated otherwise in figure legends. Consistent with a prior report from our laboratory [28], H2O2 concentrations in medium of IgG-K. pneumoniae-treated AMs (∼0.32 μM) were approximately twice those measured in untreated cells (∼0.16 μM).

Western blotting

AMs (3×106) were plated in 6-well tissue culture dishes and incubated in the presence or absence of compounds of interest and IgG-K. pneumoniae, after which they were lysed in ice-cold PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail (1 tablet/5 ml) from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set I and II (1/100) from Calbiochem. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad DC protein assay (modified Lowry protein assay) from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA). Samples containing 40 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE using 8% gels and then transferred overnight to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 4% BSA, membranes were probed overnight with commercially available Abs (titer of 1:1000, except for the Ab against β-actin: titer of 1:10,000) directed against phospho-specific or total NADPHox components or kinases. The phospho-specific Abs used recognized residues whose phosphorylation is known to be associated with activation [15, 42–45]. After incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (or anti-mouse) secondary Ab (titer of 1:10,000) from Cell Signaling Technology, film was developed using ECL detection from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Relative band densities were determined by densitometric analysis using NIH ImageJ software, and relative band densities for experimental conditions were expressed as described in figure legends. In all instances, density values of bands were corrected by subtraction of the background values.

Cell fractionation and Western blotting

AMs (4×106) were plated in 6-well tissue culture dishes and pretreated for 10 min with PGE2 or cAMP analog specific for PKA-RII. After this, AMs were lysed by sonication in ice-cold buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. The membrane (insoluble) fraction was washed and subjected to another ultracentrifugation step as described above. The resultant pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer and sonicated. Protein concentrations were determined as described above. Samples containing protein were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described above by incubating overnight with anti-phospho-p40phox, anti-p47phox (1:1000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-gp91phox (1:500; BD Biosciences), followed by peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary Ab as described above. The results were expressed as normalized phospho-p40phox/total gp91phox.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

For p40phox immunoprecipitation, macrophage monolayers were washed once and lysed in the lysis buffer described in the Western blotting section. In these experiments, the AMs were pretreated for 10 min with or without 1 μM PGE2 followed by the addition of 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min. Total protein concentrations were determined as described above. Lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-p40phox (1:80; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein A-Sepharose was added to each sample and incubated for 3 h with rotation at 4°C. The beads were washed briefly three times with lysis buffer without Triton X-100, and proteins were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels. The entire volume recovered after boiling the beads was loaded onto the gel, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes overnight. Those membranes were then incubated with Abs against Akt1 and p40phox.

RNA interference

RNA interference was performed according to a protocol provided by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). Rat AMs were transfected using lipofectamine RNAiMax reagent from Invitrogen with 100 nM nontargeting SMARTpool control or specific ON-TARGET SMARTpool Akt1 (Akt1) small interfering RNA (siRNA) from Dharmacon. After 48 h of transfection, AMs were challenged with IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min (Western blot for kinase phosphorylation) or 60 min (Amplex UltraRed for H2O2 production).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± SE from three or more independent experiments and were analyzed with the Prism 5.0 statistical program from GraphPad Software (La Jolla, CA). The group means for different treatments were compared by ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni analysis when significant differences were identified. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Kinases PKCδ, PI3K/Akt, and PAK mediate H2O2 production and p40phox activation in AMs challenged with IgG-K. pneumoniae

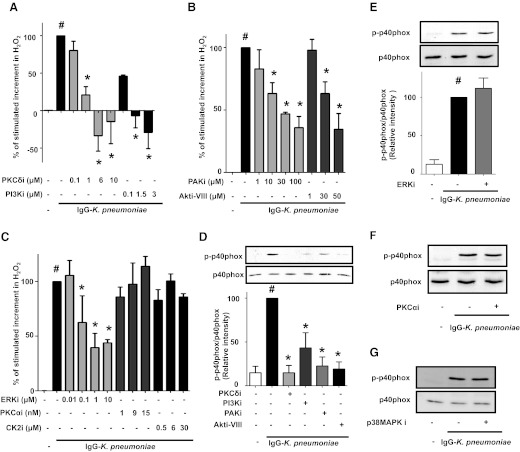

We sought to determine whether kinases known to participate in the activation of NADPHox in neutrophils or monocytes [12, 23, 24] also participate in the activation of the respiratory burst as well as of p40phox in AMs. Relatively specific kinase inhibitors were used at concentration ranges utilized in previous reports. The stimulated increment in H2O2 was dose dependently decreased by the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin (Fig. 1A), the PI3K inhibitor LY29004 (Fig. 1A), the PAK inhibitor peptide PAK18 (Fig. 1B), the Akt inhibitor Akti-VIII (Fig. 1B), the ERK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 1C), and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (not shown). As seen in Fig. 1A, H2O2 levels decreased below that found in uninfected cells at doses >6 μM rottlerin or >1.5 μM LY29004. In contrast to these data supporting a role for PKCδ, PAK, PI3K/Akt, ERK, and p38 MAPK in FcγR-triggered production of AM H2O2, inhibitor studies failed to support a role for PKCα or CK2 (Fig. 1C), because neither Ro-32-0432 nor TBB [or TBCA (not shown)], respectively, was able to significantly decrease H2O2 production induced by IgG-K. pneumoniae. Only class I isoforms produce phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), which interacts with the phox homology (PX) domain of p47phox and p40phox, yet LY29004 inhibits all 3 classes of PI3K. To determine the specific role of PI3K class I, known to be expressed in AMs [46, 47], in regulating H2O2 production, we performed additional experiments with the p110α catalytic subunit-specific inhibitor GDC-0941, the p110β subunit-specific inhibitor TGX-221, the p110γ subunit-specific inhibitor AS605240, and the p110δ subunit-specific inhibitor IC87114. We observed that all these inhibitors were effective (not shown), suggesting redundant roles for all of these class I PI3K isoforms in H2O2 induction by IgG-K. pneumoniae. To confirm that PKCδ, PI3K/Akt, PAK, p38 MAPK, and ERK mediate activation of p40phox in parallel with their role in H2O2 generation, we tested the effects of these same specific kinase inhibitors on p40phox phosphorylation on Thr154. Phosphorylation of p40phox on this residue is associated with its translocation and activation [15]. As seen in Fig. 1D, phosphorylation of p40phox in stimulated AMs was also markedly inhibited by optimal doses of the inhibitors of PKCδ, PI3K/Akt, and PAK; in contrast, the ERK inhibitor (Fig. 1E), the PKCα inhibitor (Fig. 1F), and the p38 MAPK inhibitor (Fig. 1G) had no effect on phosphorylation of p40phox.

Figure 1. Activation of the kinases PKCδ, PI3K/Akt, and PAK mediates IgG-K. pneumoniae stimulation of H2O2 generation and p40phox activation.

AMs were preincubated for 30 min with the specified doses of (A) PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin and PI3K inhibitor LY29004, (B) PAK inhibitor PAK18 and Akt inhibitor Akti-VIII, and (C) the ERK inhibitor U0126, the PKCα inhibitor Ro-32-0432, and the CK2 inhibitor TBB. They were then challenged with IgG-K. pneumoniae (MOI 50:1) for 1 h. The H2O2 concentration in medium was determined fluorometrically. (D–G) Cells were pretreated for 30 min with the inhibitors of PKCδ (6 μM), PI3K (1.5 μM), PAK (100 μM), and Akt (50 μM) (D), ERK (5 μM) (E), PKCα (15 nM) (F), and p38MAPK (10 μM) (G) noted above or in the materials and methods and then were stimulated with 50:1 opsonized K. pneumoniae for 15 min. Cells were lysed, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis of p-p40phox. Data are expressed as the percentage of stimulated increment in H2O2 (A, B, and C) and p40phox phosphorylation after quantification of blot band densities by densitometry (D and E) in cells stimulated with IgG-K. pneumoniae alone (black) and represent the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments (A–E) or as a representative blot of 2 experiments (F and G). #P < 0.05 versus untreated cells; *P < 0.05 versus IgG-K. pneumoniae alone. p, phospho; i, inhibitor.

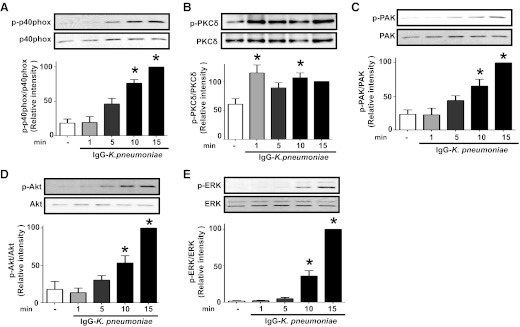

Phosphorylation of p40phox in AMs occurred in a time-dependent manner, being evident within 5 min of addition of IgG-K. pneumoniae and reaching a plateau at 10–15 min (Fig. 2A). We next determined the kinetics of activation of those kinases identified above as being involved in H2O2 regulation in stimulated AMs. PKCδ exhibited some degree of basal phosphorylation even in untreated cells; this phenomenon of basal PKC activation in AMs has been recognized previously [48]. However, upon stimulation, its degree of phosphorylation rapidly increased and peaked within 1 min (Fig. 2B), clearly preceding the phosphorylation of p40phox itself. Phosphorylation of both PAK (Fig. 2C) and Akt (Fig. 2D) occurred with kinetics corresponding to the activation of p40phox. In contrast, phosphorylation of ERK (Fig. 2E) and CK2 (not shown) was not seen until 10 min postchallenge. These kinetic data suggest that PKCδ may be an early participant in the activation of p40phox in our system, PAK and PI3K/Akt might be subsequent participants, and ERK and CK2 are unlikely to be critical contributors.

Figure 2. Kinetics of activation of p40phox and various kinases after AM stimulation with IgG-K. pneumoniae.

AMs were exposed to 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 1, 5, 10, and 15 min. Cells were lysed, proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the membranes were probed for (A) p-p40 phox, (B) p-PKCδ, (C) p-PAK, (D) p-Akt, and (E) p-ERK. Blots were analyzed by densitometry, and band densities are presented as the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments. Data are expressed as the percentage of kinase phosphorylation in cells stimulated with IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min (black). *P < 0.05 versus untreated cells. p, phospho.

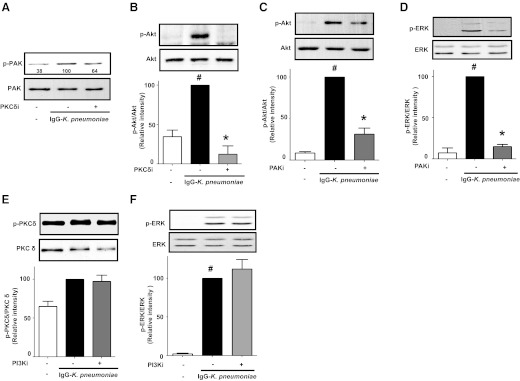

Hierarchy of kinases mediating p40phox activation and subsequent H2O2 production

PKCδ, PI3K/Akt, and PAK all participate in p40phox activation in AMs, but PKCδ appears to be the kinase activated first in response to infection. To determine the functional relationships among participating kinases, we tested the effects of specific kinase inhibitors on the phosphorylation of other kinases. The PKCδ inhibitor abrogated activation of PAK (Fig. 3A), Akt (Fig. 3B), and p38 MAPK (not shown). The PAK inhibitor decreased phosphorylation of both Akt (Fig. 3C) and ERK (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the PI3K inhibitor had no effect on phosphorylation of either PKCδ (Fig. 3E), ERK (Fig. 3F), or p38 MAPK (not shown). Taken together, these data define a temporal and functional hierarchy in AMs (depicted in the scheme in Fig. 7, left) in which PKCδ activation controls the subsequent activation of 1) PAK, which in turn mediates activation of both PI3K/Akt/p40phox and ERK as well as 2) p38 MAPKs; although these MAPKs participate in the regulation of H2O2 generation, they apparently do so in a matter independent of effects on p40phox activation. This kinase cascade ultimately results in the activation of NADPHox to produce H2O2. In contrast, PKCα and CK2 do not participate in FcγR-dependent activation of NADPHox in AMs.

Figure 3. Hierarchy of kinases controlling activation of p40phox in AMs.

AMs were treated with the PKCδ inhibitor rottlerin (6 μM) (A and B), the PAK inhibitor PAK18 (100 μM) (C and D), or the PI3K inhibitor LY29004 (1.5 μM) (E and F) for 30 min before stimulation with 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min. Cells were lysed, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis for p-PAK (A), p-Akt (B and C), p-ERK (D and F), and p-PKCδ (E). Blots were analyzed by densitometry, and results are presented as the percentage of kinase phosphorylation in cells stimulated with IgG-K. pneumoniae alone (black in B–F). (A) Blot from 1 experiment, with relative densitometric ratios noted below the p-PAK band; (B–F) data represent the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments. #P < 0.05 versus untreated cells; *P < 0.05 versus IgG-K. pneumoniae alone. p, phospho; i, inhibitor, respectively.

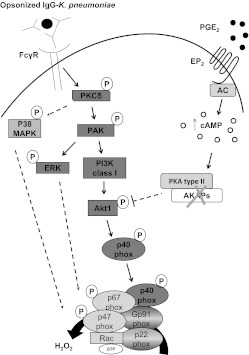

Figure 7. Scheme illustrating activation of p40phox in AMs and its inhibition by PGE2.

NADPHox is formed by a catalytic core (p22phox and gp91phox), present at the membrane, and the cytosolic subunits (p67phox, p40phox, p47phox, and Rac), which are recruited to the cell membranes under cell activation. All the components studied herein are represented in bold type. The established interactions based on the work reported here are represented by solid lines, whereas those that are incompletely characterized are represented by dashed lines. p40phox phosphorylation and ROI production in IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated AMs are regulated by a hierarchical cascade of kinases. PKCδ is rapidly activated, and this controls the subsequent activation of PAK and finally class I PI3K/Akt1. PAK itself activated ERK. p38 MAPK is activated by PKCδ. However, MAPKs do not participate in activating p40phox. Endogenous PGE2 inhibits AM p40phox activation via the second messenger cAMP acting via unanchored PKA type II to inhibit the distal kinases PI3K/Akt. No effort was made to represent the actual localization of each kinase in the cells. P, phospho; AC, adenylyl cyclase.

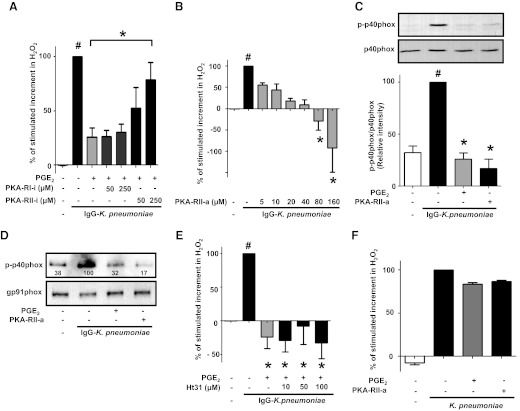

Unanchored PKA type II mediates PGE2 inhibition of H2O2 production and p40phox activation

We have previously reported that PGE2 and cAMP signaling inhibited the activation of NADPHox in AMs, with concomitant inhibition of p47phox [28]. However, to our knowledge regulation of p40phox by cAMP/PGE2 has not previously been explored in any cell type. Characterizing the network of kinases involved in activating p40phox upon IgG-K. pneumoniae challenge provided a basis for investigating their possible inhibition by PGE2 and the cAMP effector PKA.

We assessed the specific role of individual PKA isoforms in mediating the PGE2 inhibition of IgG-K. pneumoniae-induced H2O2 generation. To accomplish this, we pretreated AMs for 30 min with various doses of specific inhibitors against PKA-RI (Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS) and PKA-RII (Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS) before PGE2 addition, challenged with IgG-K. pneumoniae, and monitored H2O2 production. We previously showed that the inhibitory effects of PGE2 on H2O2 triggered by FcγR ligation were dose-dependent over the range from 10 nM to 1 μM [28], and the maximally effective dose of 1 μM PGE2 was used for these experiments. Only the PKA-RII inhibitor dose-dependently and significantly prevented the inhibitory effects of PGE2 (Fig. 4A), implicating PKA type II as an endogenous mediator of the suppressive effects of PGE2. Moreover, when added exogenously, a PKA-RII-selective agonist (6-MBC-cAMP) mimicked the inhibitory effects of PGE2 (Fig. 4B), with a dose of 160 μM completely abrogating the H2O2 production elicited by IgG-K. pneumoniae challenge. At this same dose, the specific PKA-RII agonist also completely abrogated the stimulated phosphorylation of p40phox, again reproducing the effect of PGE2 (Fig. 4C). Phosphorylation of p40phox and other cytosolic subunits of NADPHox, such as p47phox, is a prerequisite for their translocation to membranes, where they can associate with the catalytic core of the complex to carry out ROI generation [7]. We therefore examined the ability of the specific PKA-RII agonist to inhibit membrane translocation of p40phox. After IgG-K. pneumoniae challenge in the absence or presence of PGE2 or the PKA-RII agonist, membrane fractions were obtained by ultracentrifugation and immunoblotted for phospho-p40phox; levels were expressed relative to that of the constitutive membrane component gp91phox used as the loading control. Membrane content of activated p40phox was increased after stimulation, with no change in gp91phox, and both PGE2 and the PKA-RII agonist blunted the increment in membrane-associated phospho-p40phox triggered by opsonized bacteria (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Unanchored PKA type II mediates PGE2 inhibition of phosphorylation and of membrane translocation of p40phox on IgG-K. pneumoniae stimulation.

AMs were pretreated with PKA-RI and PKA-RII specific inhibitors, respectively. Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS (PKA-RI-i) and Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS (PKA-RII-i) (A) or the specific AKAP-PKA-RII peptide disruptor Ht31 (E) at the doses indicated for 30 min and then were treated for 10 min with 1 μM PGE2 (A, C, D, E, and F) or the PKA-RII agonist 6-MBC-cAMP (PKA-RII-a) at the indicated doses (B) or at 160 μM (C, D, and F) before addition of 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min (C and D) or 60 min (A, B, and E) or addition of 50:1 unopsonized K. pneumoniae for 60 min (F). Subsequently, the H2O2 concentration in medium was determined fluorometrically (A, B, E, and F). (C) Cells were lysed, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis for p-p40phox. (D) Membrane fractions from AMs treated as indicated were prepared by ultracentrifugation, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis for p-p40phox and gp91phox (membrane loading control) with relative densitometric ratios noted below the p-p40phox band. Data are expressed as the percentage of the stimulated increment in H2O2 (A, B, E, and F) or of p40phox phosphorylation (C) or p40phox translocation (D) after quantification of blot band densities by densitometry in cells stimulated with IgG-K. pneumoniae alone (black in A, B, C, and E) or stimulated with unopsonized K. pneumoniae alone (F), and represent the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments (A, B, C, and E) or 1 blot from 1 experiment, which is representative of 2 experiments (D) or the mean of 2 independent experiments (F). #P < 0.05 versus untreated cells; *P < 0.05 versus IgG-K. pneumoniae + PGE2 (A) and IgG-K. pneumoniae alone (B, C, and E). p, phospho; a, agonist; i, inhibitor.

It has been estimated that up to 75% of PKA type II molecules are bound to cellular anchoring proteins termed AKAPs [49], and we have previously shown that a PKA type II interaction with a specific AKAP mediates PGE2 inhibition of TNF-α in rat AMs [50]. To screen for involvement of AKAPs in the inhibitory actions of PGE2 on NADPHox activation in these cells, we used a cell-permeable peptide, Ht31 [51], that selectively disrupts PKA-RII-AKAP interactions. Neither this peptide disruptor, at concentrations previously shown to be effective in rat AMs [50], nor its inactive control peptide Ht31P (not shown), prevented the decrease in H2O2 production caused by PGE2 (Fig. 4E). Together, these results identify unanchored PKA type II as being responsible for the inhibition of p40phox activation caused by PGE2 and its second messenger, cAMP.

We also determined the effect of PGE2 on rat AMs challenged with unopsonized K. pneumoniae. As seen in Fig. 4F, H2O2 production in rat AMs stimulated with unopsonized K. pneumoniae was increased. However, neither PGE2 nor PKA-RII had any effect on H2O2 production triggered by unopsonized K. pneumoniae. These data suggest that the regulatory effects of PGE2 on H2O2 production are likely to be stimulus-specific.

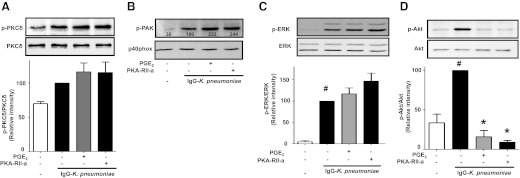

PI3K/Akt is the target for inhibition of p40phox activation by PGE2 and PKA type II

PGE2 is known to inhibit the actions of various kinases [52, 53]. Thus, we determined the extent to which PGE2/PKA type II inhibition of p40phox activation was associated with its ability to inhibit phosphorylation of the specific kinases that participate in p40phox activation upon IgG-K. pneumoniae challenge. Neither PGE2 nor the PKA-RII agonist had any effect on IgG-K. pneumoniae-triggered PKCδ phosphorylation (Fig. 5A), and the same was true for p38 MAPK phosphorylation (not shown), PAK phosphorylation (Fig. 5B) and its downstream target ERK (Fig. 5C). In contrast, both PGE2 and the PKA-RII agonist completely inhibited the increase in phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 5D), just as they inhibited the phosphorylation of p40phox (Fig. 4C). These data identify PI3K/Akt, but not the proximal activating kinases PKCδ and PAK, as a target for PKA type II action (see scheme in Fig. 7, right).

Figure 5. PKA type II and PGE2 inhibit p40phox activation in AMs by targeting PI3K/Akt.

AMs were pretreated with 1 μM PGE2 or 160 μM PKA-RII agonist 6-MBC-cAMP (PKA-RII-a) (A–D) for 10 min and then were challenged with 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min. Cells were lysed, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis for total PKCδ and p-PKCδ (A), total p40phox and p-PAK (B), total ERK and p-ERK (C), and total Akt and p-Akt (D). Blots were analyzed by densitometry, and data are expressed as the percentage of kinase phosphorylation in cells stimulated with IgG-K. pneumoniae alone (black in A, C, and D). Data represent the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments (A, C, and D), and (B) is a blot from 1 experiment with relative densitometric ratios noted below the p-PAK band. #P < 0.05 versus untreated cells; *P < 0.05 versus IgG-K. pneumoniae alone. p, phospho; a, agonist.

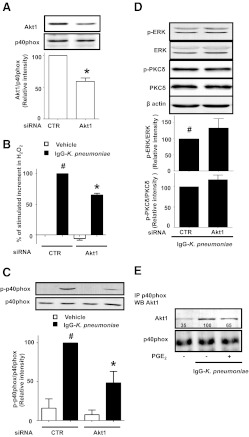

Akt1 mediates p40phox activation induced by IgG-K. pneumoniae and is a target for inhibition by PGE2/PKA type II

Because Akt appears to be a critical kinase playing a proximate role in p40phox activation as well as a target for the inhibitory actions of PGE2 and PKA, we sought to determine which Akt isoform is involved in p40phox activation. Gene silencing using siRNA offered a strategy to not only confirm the consequences of pharmacological inhibition of Akt but also to target a specific isoform of Akt. In this endeavor, we chose to specifically focus on the Akt1 isoform [54], because of data implicating this isoform in p40phox regulation in neutrophils [22, 55]. In addition, the inhibitor Akti-VIII, which inhibited both H2O2 generation (Fig. 1B) and p40phox phosphorylation (Fig. 1D), exhibits relative specificity for Akt1 [56]. Compared with nontargeting control siRNA, Akt1 siRNA in AMs resulted in Akt1 protein knockdown of ∼40–50% (Fig. 6A), a degree of knockdown similar to that which we have obtained previously for other proteins in primary alveolar macrophages [50]. p40phox was used as a loading control in this experiment to exclude the possibility that the decrease in phosphorylated p40phox shown in Fig. 6C was due to a decrease in total p40phox expression. As also seen in Fig. 6D, expression of total ERK, PKCδ, and β-actin was not affected by Akt1 protein knockdown. Stimulated H2O2 production was concomitantly decreased by ∼40% in cells pretreated with Akt1 siRNA (Fig. 6B). Moreover, Akt1 knockdown reduced the activation of p40phox in AMs stimulated by IgG-K. pneumoniae by ∼50% (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these data support a role for Akt1 in p40phox and NADPHox activation. As seen in Fig. 6B and C, even baseline levels of both H2O2 generation and p40phox activation were slightly decreased in unstimulated cells whose Akt1 was knocked down. However, neither ERK nor PKCδ phosphorylation (Fig. 6D) in IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated cells was attenuated in Akt1-silenced AMs. PGE2 was still able to decrease H2O2 production even in Akt1-silenced cells (not shown), probably reflecting both the incomplete nature of silencing and its ability to also regulate activation of p47phox [28].

Figure 6. Akt1 is the isoform regulating p40phox activation in AMs.

AMs were pretreated for 48 h with nontargeting control (CTR) or Akt1 (Akt1) siRNA (A–D) and then were stimulated with 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae (black) for 1 h (B) or 15 min (C and D). (B) The H2O2 concentration in medium was determined fluorometrically. (A, C, and D) Cells were lysed, and proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis for (A) Akt1, (C and D) p-p40phox, or (D) p-ERK and p-PKCδ. (E) Cells were pretreated for 10 min with or without PGE2 followed by the addition of 50:1 IgG-K. pneumoniae for 15 min. Cells were lysed, and p40phox was immunoprecipitated using a specific Ab. Then the p40phox immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis for Akt1 and p40phox. Data are expressed as the relative percentage to the following groups: (A) nontargeting control siRNA (CTR), (B–D) IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated cells pretreated with siRNA CTR, or (E) IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated cells. Data represent the mean ± se from at least 3 independent experiments (A–D) or a representative blot from 2 experiments (E); in the latter, relative densitometric ratios are noted below the Akt1 band. #P < 0.05 versus unstimulated cells pretreated with siRNA CTR; *P < 0.05 versus unstimulated (A) or IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated (B and C) cells pretreated with siRNA CTR. p, phospho; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot.

To evaluate a possible direct interaction between Akt1 and its proximal target p40phox, we immunoprecipitated p40phox, and then sought the presence of Akt1 in the immunoprecipitate. As seen in Fig. 6E, coimmunoprecipitation of p40phox and Akt1 was enhanced by stimulation with IgG-K. pneumoniae, and this association was attenuated by PGE2. However, these same p40phox immunoprecipitates contained no immunodetectable PKCδ (not shown), supporting the contention that Akt1 is directly upstream of p40phox and that PKCδ is not.

DISCUSSION

Among NADPHox cytosolic subunits, p40phox is now recognized as more than a passive p67phox partner whose translocation is directed by p47phox [20–22]. Rather, emerging evidence indicates that it too can function as a carrier of other cytosolic subunits and as an active regulator of NADPHox [15–22], with defects in ROI production and bacterial killing identified in p40phox−/− mice [16]. However, its regulation is incompletely understood. In particular, nothing is known about p40phox activation in AMs or its regulation by PGE2 in any cell type. The critical importance of these issues derives from the clinical impact of respiratory infections globally, the role of AMs as resident innate defenders of the distal lung, and the ability of PGE2 to exert profound immunosuppressive actions on leukocytes at sites of infection. Our key findings are summarized in the scheme depicted in Fig. 7: we defined a kinase cascade responsible for p40phox activation in AMs activated via FcγR ligation in which PKCδ is upstream of PAK, which is upstream of class I PI3K/Akt1. In contrast, we were unable to identify roles for PKCα, ERK, p38 MAPK, or CK2 in this process. PGE2 effects, which we have previously linked with signaling via the EP2 and EP4 receptors and the cAMP effector PKA [28], were shown here to be mediated by AKAP-unanchored PKA type II, targeting only the most downstream of the regulatory kinases, class I PI3K/Akt1, culminating in p40phox inhibition.

Chessa et al. [15] reported that phosphorylation of p40phox on Thr154 by PKCδ is associated with full NADPHox activation in neutrophils. Our results define PKCδ as a very early participant in oxidase activation in AMs as well. On the basis of the actions of inhibitors and siRNA as well as the kinetics of phosphorylation, our data suggest that PKCδ was upstream of class I PI3K/Akt1 in this experimental system. PI3K has often been identified as being very proximal in FcγR signaling and upstream of PKCδ. Indeed, Toker et al. [57] suggested that the PI3K product PIP3 could activate PKCδ, and in HL-60 cells differentiated to a neutrophil-like phenotype, Yamamori et al. [58] showed that PI3K controlled p47phox phosphorylation in a PKCδ-dependent manner. In contrast, Hazeki et al. [59] reported that in murine RAW264.7 macrophages, PKCδ regulated PI3K, albeit in a negative manner. The relative importance of species, cell type, culture conditions, and stimulus in explaining these differences remains to be defined.

We used rottlerin as a PKCδ inhibitor in the present studies. Although the off target effects of this compound have been identified [60], these have generally been observed at concentrations ≥ 10μM, whereas we observed 90% inhibition of H2O2 production induced by opsonized K. pneumoniae at the low rottlerin dose of 1 μM.

PAK is an effector of Rac that has been shown to participate in NADPHox activation in neutrophils [61]. However, neither its expression nor its participation in regulating NADPHox has been investigated previously in AMs. Our studies in IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated AMs reveal that PAK is activated after PKCδ and identify it as being necessary for Akt1 activation, ROI production, and p40phox activation. PAK has been suggested to be activated downstream of PI3K [62], but our inhibitor data once again place PAK upstream of class I PI3K/Akt1 in this experimental system and upstream of ERK. Indeed, the ERK kinase MEK-1 has been reported to be a direct substrate of PAK [63], possibly explaining why ERK activation is delayed. Although PAK exists as many distinct isoforms, it is likely that PAK2 is the isoform involved in regulating p40phox activation in rat AMs. First, the total PAK Ab used is relatively specific for PAK2, suggesting that this isoform is present in AMs. Second, although the anti-phospho-PAK Ab used herein recognizes multiple phosphorylated isoforms, the molecular weight of the single band appearing on our Western blots is consistent only with PAK2. Third, although PAK2 has a ubiquitous tissue distribution, PAK1 is highly expressed only in brain, muscle, and spleen [64]. The possibility that Rac participates in PAK activation in this system requires further investigation.

Data on the kinetics of Akt activation, on the effects of inhibitors of both PI3K and Akt as well as silencing of Akt1, and on its coimmunoprecipitation with p40phox place the class I PI3K/Akt1 axis proximal to activation of p40phox itself. In neutrophil-like cells, Akt has been suggested to play a major role in membrane recruitment of p47phox and p67phox on N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine stimulation [14, 65], and it has been reported to phosphorylate p47phox in vivo [14] in neutrophils. Thr154, the phosphorylation site on p40phox which is recognized by the phospho-Ab used, comprises the terminal residue of a RLRPRT sequence, which coincides with a consensus Akt phosphorylation motif, RXRXXS/T. In neutrophils, Akt2−/− mice produced 75% less ROI, with Akt1 having no effect [55], and activation of p47phox was reduced, suggesting that Akt2 regulates p47phox. Moreover, it has been shown that platelet-activating factor induced p67phox and p40phox phosphorylation and translocation in neutrophils in a manner dependent on PI3K/Akt1 but independent of p47phox [22]. Such data highlight the potential for distinct and independent means of regulating the activation of specific cytosolic subunits of NADPHox. Understanding the possible involvement of Akt2 in p40phox regulation and the interrelationships between p40phox and p47phox activation and translocation in our model will require additional investigation.

The PI3K product PIP3 also has the ability to bind to the PX domain of p40phox [24]. Together with direct phosphorylation by Akt1, this mechanism may contribute to activation of p40phox by the PI3K/Akt axis in AMs. The ability of multiple subunit-selective inhibitors to inhibit ROI generation in IgG-K. pneumoniae-stimulated AMs suggests that different catalytic subunits of class I PI3K have the potential to regulate p40phox, indicating a degree of redundancy among those isoforms as has previously been observed between p110β and p110γ in macrophages by Guillermet-Guibert et al [66].

Among MAPKs, we mainly focused on ERK because of its well-known ability to contribute to NADPHox activation [67–69] and to activation of various antimicrobial functions in AMs [53, 70]. However, the present studies suggest that although ERK is activated in AMs challenged with IgG-K. pneumoniae and involved in H2O2 production, it does not regulate p40phox activation. Instead, its participation in NADPHox activation may reflect its effects on p47phox. The same pattern of findings applied to p38 MAPK, contrasting with what has been observed in neutrophils [22].

We have previously demonstrated that AMs express both PKA-RI and -RII isoforms, and that both PKA type I and PKA type II can modulate expression of specific cytokines [50]. The current studies with PKA-R isoform-specific agonists and inhibitors as well as AKAP disruptor peptides identified unanchored PKA type II as being both capable of inhibiting p40phox activation and mediating the inhibition of this process by PGE2 in IgG-K. pneumoniae-triggered AMs. This inhibitory action appeared to be directed at the class I PI3K/Akt1 axis and not at more upstream kinases in the hierarchy controlling p40phox activation. This is to our knowledge the first report describing inhibition of p40phox by the PGE2/cAMP/PKA axis in macrophages or in any leukocyte population. The molecular basis for the preferential role of PKA type II over PKA type I in PGE2 inhibition of the activation of both PI3K/Akt and p40phox is uncertain at the present time. It could reflect differential sensitivities to cAMP of the two PKA isoforms [71–73] or differences in their subcellular localization. Notably, both PKA type II [71, 73] and PI3K/Akt [74, 75] have been reported to be recruited to phagosomes where bacterial killing by NADPHox occurs. This is in keeping with the report of Rivard et al. [76], who showed that PKA type II localized to dynamic actin microspikes without participation of AKAPs. Thus, class I PI3K/Akt1 is positioned at the junction of transduction pathways activated by opsonized K. pneumoniae and PGE2/cAMP/PKA.

The mechanism by which PKA type II inhibits PI3K/Akt remains to be defined, but we can speculate about several possibilities. First, PKA might directly phosphorylate PI3K. There is precedent for phosphorylation by PKA of PI3K class I regulatory subunit p85α at Ser83, although this had activating rather than inhibitory consequences [77], and to our knowledge an inhibitory phosphorylation site on PI3K has not been described. Second, it is possible that even an activating phosphorylation of PI3K by PKA allosterically interferes with the subsequent activation of PDK1 or PDK2, or its direct substrate, Akt, and there is precedent for the latter phenomenon [78]. Third, cAMP via PKA might inhibit Akt activation directly, thereby blocking PDK recruitment to the membrane. It is unlikely that PDK1 was involved in p40phox regulation in our experimental system, because an inhibitor of this kinase failed to attenuate p40phox phosphorylation levels induced by IgG-K. pneumoniae (not shown). However a possible role for PDK2 or mammalian target of rapamycin [79] mediating the phosphorylation of Akt is not excluded and will need further investigation. A final possibility is that PGE2/cAMP/PKA abrogates PI3K signaling by activation of phosphatases. One first candidate was PTEN. PTEN is a dual protein/lipid phosphatase that opposes the actions of PI3K by dephosphorylating PI3K-derived PIP3 to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Indeed, we have previously reported [53] that PGE2 activates the phosphatase activity of PTEN in AMs by dephosphorylating it on Tyr residues. However, our data indicate that although it may participate, PTEN is not the only phosphatase mediating Akt inhibition because the decrease in stimulated H2O2 elicited by PGE2 and PKA-RII was minimally abrogated by a PTEN inhibitor (not shown). Alternatively, a phosphatase other than PTEN might be activated, and in this regard, Zhang et al. [80] have described PKA activation of SH2 (Src homology 2)-containing inositol phosphatase-1.

The ability of PGE2 to inhibit the respiratory burst was evident when AMs were stimulated by IgG-K. pneumoniae but not by unopsonized bacteria. This difference highlights the stimulus specificity of oxidase regulation, but the precise differences in activation cascades and their control by this prostanoid remain to be elucidated in future investigations.

In summary, our studies have defined the organization of the kinase network that controls activation of p40phox in AMs. In addition, we have identified a distal component of that network, the class I PI3K/Akt1 axis, as the target by which PGE2 via PKA type II inhibits p40phox activation in this model. Because commonly used therapeutic agents such as glucocorticoids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit the biosynthesis of PGE2, these findings provide relevant new insights into the regulation of AM antimicrobial functions and lung innate immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants HL103777 (C.H.S.), HD057176 (D.M.A.), and HL058897 (M.P.-G.) and an American Lung Association Senior Research Training Fellowship (E.B.).

Footnotes

- AKAP

- A-kinase anchoring protein

- AM

- alveolar macrophage

- Akti-VIII

- Akt inhibitor

- C

- catalytic subunit of PKA

- CK2

- casein kinase 2

- EP

- E prostanoid

- FcγR

- Fcγ receptor

- IgG-K. pneumoniae

- IgG-opsonized K. pneumoniae

- 6-MBC-cAMP

- PKA-RII-selective activator N6-mono-t-butylcarbamoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- MOI

- multiple of infection

- NADPHox

- NADPH oxidase

- p110

- class I PI3K catalytic subunit

- PAK

- p21-activated protein kinase

- PDK

- phosphoinositide-dependent kinase

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10

- PX

- phox homology

- R

- regulatory subunit of PKA

- ROI

- reactive oxygen intermediate

- Rp-8-Cl-cAMPS

- PKA RI-selective inhibitor 8-chloroadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer

- Rp-8-PIP-cAMPS

- PKA RII-selective inhibitor 8-piperidinoadenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TBB

- 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole

- TBCA

- (E)-3-(2,3,4,5-tetrabromophenyl)acrylic acid

AUTHORSHIP

E.B. designed the research, performed experiments, collected, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. C.H.S., D.M.A., and M.P.-G. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. M.P.-G. supervised the work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Murray C. J., Lopez A. D. (1997) Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349, 1269–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mizgerd J. P. (2006) Lung infection—a public health priority. PLoS Med. 3, e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold R. S., Thom K. A., Sharma S., Phillips M., Kristie Johnson J., Morgan D. J. (2011) Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. South. Med. J. 104, 40–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laskin D. L., Weinberger B., Laskin J. D. (2001) Functional heterogeneity in liver and lung macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70, 163–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serezani C. H., Aronoff D. M., Jancar S., Mancuso P., Peters-Golden M. (2005) Leukotrienes enhance the bactericidal activity of alveolar macrophages against Klebsiella pneumoniae through the activation of NADPH oxidase. Blood 106, 1067–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hickman-Davis J. M., O'Reilly P., Davis I. C., Peti-Peterdi J., Davis G., Young K. R., Devlin R. B., Matalon S. (2002) Killing of Klebsiella pneumoniae by human alveolar macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 282, L944–L956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Babior B. M. (2004) NADPH oxidase. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16, 42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee S., Feinstein S. I., Dodia C., Sorokina E., Lien Y. C., Nguyen S., Debolt K., Speicher D., Fisher A. B. (2011) Peroxiredoxin 6 phosphorylation and subsequent phospholipase A2 activity are required for agonist-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelium and alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11696–11706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bellavite P. (1988) The superoxide-forming enzymatic system of phagocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 4, 225–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faust L. R., el Benna J., Babior B. M., Chanock S. J. (1995) The phosphorylation targets of p47phox, a subunit of the respiratory burst oxidase. Functions of the individual target serines as evaluated by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 96, 1499–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. El Benna J., Faust R. P., Johnson J. L., Babior B. M. (1996) Phosphorylation of the respiratory burst oxidase subunit p47phox as determined by two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C, protein kinase A, and a mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6374–6378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El-Benna J., Dang P. M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., Marie J. C., Braut-Boucher F. (2009) p47phox, the phagocyte NADPH oxidase/NOX2 organizer: structure, phosphorylation and implication in diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 41, 217–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cathcart M. K. (2004) Regulation of superoxide anion production by NADPH oxidase in monocytes/macrophages: contributions to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Q., Powell D. W., Rane M. J., Singh S., Butt W., Klein J. B., McLeish K. R. (2003) Akt phosphorylates p47phox and mediates respiratory burst activity in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 170, 5302–5308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chessa T. A., Anderson K. E., Hu Y., Xu Q., Rausch O., Stephens L. R., Hawkins P. T. (2010) Phosphorylation of threonine 154 in p40phox is an important physiological signal for activation of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Blood 116, 6027–6036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellson C. D., Davidson K., Ferguson G. J., O'Connor R., Stephens L. R., Hawkins P. T. (2006) Neutrophils from p40phox−/− mice exhibit severe defects in NADPH oxidase regulation and oxidant-dependent bacterial killing. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1927–1937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suh C. I., Stull N. D., Li X. J., Tian W., Price M. O., Grinstein S., Yaffe M. B., Atkinson S., Dinauer M. C. (2006) The phosphoinositide-binding protein p40phox activates the NADPH oxidase during FcγIIA receptor-induced phagocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1915–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matute J. D., Arias A. A., Wright N. A., Wrobel I., Waterhouse C. C., Li X. J., Marchal C. C., Stull N. D., Lewis D. B., Steele M., Kellner J. D., Yu W., Meroueh S. O., Nauseef W. M., Dinauer M. C. (2009) A new genetic subgroup of chronic granulomatous disease with autosomal recessive mutations in p40phox and selective defects in neutrophil NADPH oxidase activity. Blood 114, 3309–3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuribayashi F., Nunoi H., Wakamatsu K., Tsunawaki S., Sato K., Ito T., Sumimoto H. (2002) The adaptor protein p40phox as a positive regulator of the superoxide-producing phagocyte oxidase. EMBO J. 21, 6312–6320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ueyama T., Tatsuno T., Kawasaki T., Tsujibe S., Shirai Y., Sumimoto H., Leto T. L., Saito N. (2007) A regulated adaptor function of p40phox: distinct p67phox membrane targeting by p40phox and by p47phox. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 441–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ueyama T., Nakakita J., Nakamura T., Kobayashi T., Son J., Sakuma M., Sakaguchi H., Leto T. L., Saito N. (2011) Cooperation of p40phox with p47phox for Nox2 activation during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis—mechanism for acquisition of p40phox PI(3)P binding. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40693–40705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McLaughlin N. J., Banerjee A., Khan S. Y., Lieber J. L., Kelher M. R., Gamboni-Robertson F., Sheppard F. R., Moore E. E., Mierau G. W., Elzi D. J., Silliman C. C. (2008) Platelet-activating factor-mediated endosome formation causes membrane translocation of p67phox and p40phox that requires recruitment and activation of p38 MAPK, Rab5a, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 180, 8192–820318523285 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bey E. A., Xu B., Bhattacharjee A., Oldfield C. M., Zhao X., Li Q., Subbulakshmi V., Feldman G. M., Wientjes F. B., Cathcart M. K. (2004) Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J. Immunol. 173, 5730–5738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hawkins P. T., Davidson K., Stephens L. R. (2007) The role of PI3Ks in the regulation of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 74, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brock T. G., Peters-Golden M. (2007) Activation and regulation of cellular eicosanoid biosynthesis. ScientificWorldJournal. 7, 1273–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tilley S. L., Coffman T. M., Koller B. H. (2001) Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 15–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asai T., Okada M., Yokomizo Y., Sato S., Mori Y. (1996) Suppressive effect of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from pigs infected with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae on chemiluminescence of porcine peripheral neutrophils. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 51, 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Serezani C. H., Chung J., Ballinger M. N., Moore B. B., Aronoff D. M., Peters-Golden M. (2007) Prostaglandin E2 suppresses bacterial killing in alveolar macrophages by inhibiting NADPH oxidase. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 37, 562–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ballinger M. N., Aronoff D. M., McMillan T. R., Cooke K. R., Olkiewicz K., Toews G. B., Peters-Golden M., Moore B. B. (2006) Critical role of prostaglandin E2 overproduction in impaired pulmonary host response following bone marrow transplantation. J. Immunol. 177, 5499–5508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sadikot R. T., Zeng H., Azim A. C., Joo M., Dey S. K., Breyer R. M., Peebles R. S., Blackwell T. S., Christman J. W. (2007) Bacterial clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is enhanced by the inhibition of COX-2. Eur. J. Immunol. 37, 1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cayeux S. J., Beverley P. C., Schulz R., Dorken B. (1993) Elevated plasma prostaglandin E2 levels found in 14 patients undergoing autologous bone marrow or stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 12, 603–608 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Starczewski M., Voigtmann R., Peskar B. A., Peskar B. M. (1984) Plasma levels of 15-keto-13,14-dihydro-prostaglandin E2 in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Prostaglandins Leukot. Med. 13, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hayek M. G., Meydani S. N., Meydani M., Blumberg J. B. (1994) Age differences in eicosanoid production of mouse splenocytes: effects on mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation. J. Gerontol. 49, B197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stapleton P. P., Fujita J., Murphy E. M., Naama H. A., Daly J. M. (2001) The influence of restricted calorie intake on peritoneal macrophage function. Nutrition 17, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strandvik B., Svensson E., Seyberth H. W. (1996) Prostanoid biosynthesis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acid. 55, 419–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Serezani C. H., Ballinger M. N., Aronoff D. M., Peters-Golden M. (2008) Cyclic AMP: master regulator of innate immune cell function. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39, 127–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lattin J., Zidar D. A., Schroder K., Kellie S., Hume D. A., Sweet M. J. (2007) G-protein-coupled receptor expression, function, and signaling in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 16–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aronoff D. M., Canetti C., Serezani C. H., Luo M., Peters-Golden M. (2005) Cutting edge: Macrophage inhibition by cyclic AMP (cAMP): differential roles of protein kinase A and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP-1. J. Immunol. 174, 595–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gold M. G., Lygren B., Dokurno P., Hoshi N., McConnachie G., Tasken K., Carlson C. R., Scott J. D., Barford D. (2006) Molecular basis of AKAP specificity for PKA regulatory subunits. Mol. Cell 24, 383–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mancuso P., Standiford T. J., Marshall T., Peters-Golden M. (1998) 5-Lipoxygenase reaction products modulate alveolar macrophage phagocytosis of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 66, 5140–5146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhan Q., Ge Q., Ohira T., Van Dyke T., Badwey J. A. (2003) p21-activated kinase 2 in neutrophils can be regulated by phosphorylation at multiple sites and by a variety of protein phosphatases. J. Immunol. 171, 3785–3793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boulton T. G., Nye S. H., Robbins D. J., Ip N. Y., Radziejewska E., Morgenbesser S. D., DePinho R. A., Panayotatos N., Cobb M. H., Yancopoulos G. D. (1991) ERKs: a family of protein-serine/threonine kinases that are activated and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to insulin and NGF. Cell 65, 663–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alessi D. R., Andjelkovic M., Caudwell B., Cron P., Morrice N., Cohen P., Hemmings B. A. (1996) Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 15, 6541–6551 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Keranen L. M., Dutil E. M., Newton A. C. (1995) Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr. Biol. 5, 1394–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Konrad S., Ali S. R., Wiege K., Syed S. N., Engling L., Piekorz R. P., Hirsch E., Nurnberg B., Schmidt R. E., Gessner J. E. (2008) Phosphoinositide 3-kinases gamma and delta, linkers of coordinate C5a receptor-Fcγ receptor activation and immune complex-induced inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33296–33303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Monick M. M., Robeff P. K., Butler N. S., Flaherty D. M., Carter A. B., Peterson M. W., Hunninghake G. W. (2002) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity negatively regulates stability of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32992–33000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Peters-Golden M., McNish R. W., Sporn P. H., Balazovich K. (1991) Basal activation of protein kinase C in rat alveolar macrophages: implications for arachidonate metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 261, L462–L471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong W., Scott J. D. (2004) AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 959–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim S. H., Serezani C. H., Okunishi K., Zaslona Z., Aronoff D. M., Peters-Golden M. (2011) Distinct protein kinase A anchoring proteins direct prostaglandin E2 modulation of Toll-like receptor signaling in alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8875–8883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carr D. W., Hausken Z. E., Fraser I. D., Stofko-Hahn R. E., Scott J. D. (1992) Association of the type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase with a human thyroid RII-anchoring protein. Cloning and characterization of the RII-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 13376–13382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. White E. S., Atrasz R. G., Dickie E. G., Aronoff D. M., Stambolic V., Mak T. W., Moore B. B., Peters-Golden M. (2005) Prostaglandin E2 inhibits fibroblast migration by E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in PTEN activity. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32, 135–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Canetti C., Serezani C. H., Atrasz R. G., White E. S., Aronoff D. M., Peters-Golden M. (2007) Activation of phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 mediates the inhibition of FcγR phagocytosis by prostaglandin E2 in alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol. 179, 8350–8356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chang T., Wang R., Olson D. J., Mousseau D. D., Ross A. R., Wu L. (2011) Modification of Akt1 by methylglyoxal promotes the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 25, 1746–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen J., Tang H., Hay N., Xu J., Ye R. D. (2010) Akt isoforms differentially regulate neutrophil functions. Blood 115, 4237–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lindsley C. W., Zhao Z., Leister W. H., Robinson R. G., Barnett S. F., Defeo-Jones D., Jones R. E., Hartman G. D., Huff J. R., Huber H. E., Duggan M. E. (2005) Allosteric Akt (PKB) inhibitors: discovery and SAR of isozyme selective inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15, 761–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toker A., Meyer M., Reddy K. K., Falck J. R., Aneja R., Aneja S., Parra A., Burns D. J., Ballas L. M., Cantley L. C. (1994) Activation of protein kinase C family members by the novel polyphosphoinositides PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32358–32367 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamamori T., Inanami O., Nagahata H., Kuwabara M. (2004) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates the phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase component p47phox by controlling cPKC/PKCδ but not Akt. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 720–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hazeki K., Inoue K., Nigorikawa K., Hazeki O. (2009) Negative regulation of class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase by protein kinase Cδ limits Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J. Biochem. 145, 87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Soltoff S. P. (2007) Rottlerin: an inappropriate and ineffective inhibitor of PKCδ. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 453–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Martyn K. D., Kim M. J., Quinn M. T., Dinauer M. C., Knaus U. G. (2005) p21-activated kinase (Pak) regulates NADPH oxidase activation in human neutrophils. Blood 106, 3962–3969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Knaus U. G., Morris S., Dong H. J., Chernoff J., Bokoch G. M. (1995) Regulation of human leukocyte p21-activated kinases through G protein–coupled receptors. Science 269, 221–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Park E. R., Eblen S. T., Catling A. D. (2007) MEK1 activation by PAK: a novel mechanism. Cell. Signal. 19, 1488–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sells M. A., Chernoff J. (1997) Emerging from the Pak: the p21-activated protein kinase family. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patel S., Djerdjouri B., Raoul-Des-Essarts Y., Dang P. M., El-Benna J., Perianin A. (2010) Protein kinase B (AKT) mediates phospholipase D activation via ERK1/2 and promotes respiratory burst parameters in formylpeptide-stimulated neutrophil-like HL-60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32055–32063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Guillermet-Guibert J., Bjorklof K., Salpekar A., Gonella C., Ramadani F., Bilancio A., Meek S., Smith A. J., Okkenhaug K., Vanhaesebroeck B. (2008) The p110beta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals downstream of G protein-coupled receptors and is functionally redundant with p110γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 8292–8297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dewas C., Fay M., Gougerot-Pocidalo M. A., El-Benna J. (2000) The mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway is involved in formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-induced p47phox phosphorylation in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 165, 5238–5244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hazan-Halevy I., Levy T., Wolak T., Lubarsky I., Levy R., Paran E. (2005) Stimulation of NADPH oxidase by angiotensin II in human neutrophils is mediated by ERK, p38 MAP-kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2. J. Hypertens. 23, 1183–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pandey D., Fulton D. J. (2011) Molecular regulation of NADPH oxidase 5 via the MAPK pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H1336–H1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Garcia-Garcia E., Rosales R., Rosales C. (2002) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase are recruited for Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 72, 107–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hayes J. S., Brunton L. L., Mayer S. E. (1980) Selective activation of particulate cAMP-dependent protein kinase by isoproterenol and prostaglandin E1. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 5113–5119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zaccolo M., Pozzan T. (2002) Discrete microdomains with high concentration of cAMP in stimulated rat neonatal cardiac myocytes. Science 295, 1711–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jarnaess E., Tasken K. (2007) Spatiotemporal control of cAMP signalling processes by anchored signalling complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 931–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Allen L. A., Allgood J. A., Han X., Wittine L. M. (2005) Phosphoinositide3-kinase regulates actin polymerization during delayed phagocytosis of Helicobacter pylori. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78, 220–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ellson C. D., Anderson K. E., Morgan G., Chilvers E. R., Lipp P., Stephens L. R., Hawkins P. T. (2001) Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is generated in phagosomal membranes. Curr. Biol. 11, 1631–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Rivard R. L., Birger M., Gaston K. J., Howe A. K. (2009) AKAP-independent localization of type-II protein kinase A to dynamic actin microspikes. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 693–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cosentino C., Di Domenico M., Porcellini A., Cuozzo C., De Gregorio G., Santillo M. R., Agnese S., Di Stasio R., Feliciello A., Migliaccio A., Avvedimento E. V. (2007) p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K mediates cAMP-PKA and estrogens biological effects on growth and survival. Oncogene 26, 2095–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wu W. I., Voegtli W. C., Sturgis H. L., Dizon F. P., Vigers G. P., Brandhuber B. J. (2010) Crystal structure of human AKT1 with an allosteric inhibitor reveals a new mode of kinase inhibition. PLoS One 5, e12913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chan T. O., Tsichlis P. N. (2001) PDK2: a complex tail in one Akt. Sci. STKE 2001, pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang J., Ravichandran K. S., Garrison J. C. (2010) A key role for the phosphorylation of Ser440 by the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in regulating the activity of the Src homology 2 domain-containing Inositol 5′-phosphatase (SHIP1). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34839–34849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]