Abstract.

Polarization-gated spectroscopy is an established method to depth-selectively interrogate the structural properties of biological tissue. We employ this method in vivo in the azoxymethane (AOM)-treated rat model to monitor the morphological changes that occur in the field of a tumor during early carcinogenesis. The results demonstrate a statistically significant change in the shape of the refractive-index correlation function for AOM-treated rats versus saline-treated controls. Since refractive index is linearly proportional to mass density, these refractive-index changes can be directly linked to alterations in the spatial distribution patterns of macromolecular density. Furthermore, we found that alterations in the shape of the refractive-index correlation function shape were an indicator of both present and future risk of tumor development. These results suggest that noninvasive measurement of the shape of the refractive-index correlation function could be a promising marker of early cancer development.

Keywords: biomedical optics, endoscopy, fiber optics, polarization, refractive index, scattering

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer deaths in Americans despite being highly treatable in its early stages.1 This reflects both the lack of conspicuous symptoms in CRC’s early stages and the lack of compliance with CRC screening guidelines. Colonoscopy is the current gold standard for CRC screening of the at-risk population because of its outstanding accuracy in detecting advanced neoplastic lesions and its simultaneous ability to reduce the CRC incidence by endoscopic removal of these lesions.2,3 However, due to concerns of cost, invasiveness, discomfort with bowel cleansing, and potential complications, the majority of eligible screening participants forgo the colonoscopy exam. Even if compliance could be improved, it would impose heavy financial and resource burdens on the healthcare system.4 Consequently, there have been recent attempts to find more cost-effective and/or less invasive methods of CRC screening. Among the best known are fecal occult blood testing, fecal DNA analysis, sigmoidoscopy, and computed-tomography (CT) colography. Issues of diagnostic sensitivity5,6 and ionizing radiation in the case of CT colography have prevented these methods from gaining widespread acceptance.

The weaknesses of colonoscopy and the current alternatives underscore the need for additional methods of CRC screening. One promising avenue is based on the field effect concept in carcinogenesis: The genetic and environmental milieu that results in a focal lesion should be detectable, at least in some form, throughout the colonic mucosa. For CRC screening, minimally invasive measurements from the rectum could be diagnostic of early carcinogenesis throughout the colon. Our laboratory has previously employed a suite of biophotonic technologies to demonstrate that changes in rectal optical signatures are indicative of premalignant lesions throughout the colon.7–9

One of the technologies we have used is known as polarization-gated spectroscopy. Interrogation of tissue structure with polarized light has found numerous applications in biomedical optics, particularly for its ability to suppress multiply scattered light.10,11 In this paper, we both demonstrate how the shape of the refractive-index correlation function can be extracted from the polarization-gated signals and present in vivo evidence from a well-controlled and established azoxymethane (AOM)-treated rat model of colon carcinogenesis that the refractive-index correlation shape can predict the risk of current and future neoplastic development throughout the colon. Changes in the shape of the refractive-index correlation function characterized by the fractal dimension have been implicated as an important parameter discriminating normal versus dysplastic tissue.12–15 Furthermore, since tissue refractive index is linearly dependent on macromolecular mass density,16 the shape of the refractive-index correlation can be directly employed to assess tissue mass-density organization and structure. Consequently, there has been growing interest in developing models and techniques to measure the spatial correlations of the refractive-index properties of tissue. Our study employs a well-characterized polarization-gated spectroscopy probe17 and the Whittle-Matérn refractive-index correlation model18 to depth-selectively quantify the refractive-index correlation shape of the AOM rat model. Using this methodology, we demonstrate an association between early colon field carcinogenesis and alterations in the refractive-index correlation function shape in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Whittle-Matérn Model of Tissue Refractive-Index Distribution

The Whittle-Matérn correlation family is a three-parameter model that has been used to describe spatially continuous refractive-index fluctuations and is represented by the equation:

| (1) |

where the parameters and denote the index correlation distance, and the shape of refractive-index correlation function, respectively, while represents the modified Bessel function of the second kind and is a normalization constant. The normalization factor ensures that is equal to the variance of the refractive-index fluctuations and has the following form:

| (2) |

where is introduced to bound when approaches zero such that (Ref. 18). When is between 1.5 and 2, the shape of the refractive-index correlation function follows a stretched exponential function. A value of results in an exponential shape while as , the shape converges to a Gaussian distribution. It has been shown that when (where is the wavenumber) and , the reduced scattering coefficient is proportional to (Ref. 18). Values of , however, cannot be recovered spectrally in the limit since the wavelength dependence becomes independent of in this region. Tissue is believed to have an value between 1 and 2 and thus the value of can be retrieved from the wavelength dependence of the signal intensity if the signal intensity has a known functional relationship with according to the following equation:

| (3) |

where is the signal intensity, f is the functional relationship between and , and is a constant from the proportionality between and . We derived the functional relationship for the polarization-gated signals using polarization-sensitive Monte Carlo (MC) that employed the Whittle-Matérn model.

2.2. Polarization-Sensitive MC Simulations Using the Whittle-Matérn Model

Publicly available polarized-light MC algorithms developed by Ramella-Roman et al.19 were used to simulate the propagation and collection of polarized light. The implementation of this algorithm to track photons as functions of polarization, radius, , and maximum depth travelled () has been described in detail by Turzhitsky et al.17 Reflection, refraction, and alteration of the Stokes vector at the sample/environment interface was computed using Snell’s Law and the Stokes formalism of the Fresnel equations.20 To employ the Whittle-Matérn model described in the previous section, we used a phase function derived from Eq. (1). First, the spectral density at spatial frequency can be calculated from the Fourier transform of yielding

| (4) |

Then, following the derivation of Moscoso et al.,21 the phase function for incident light with initial Stokes vector can be written as

| (5) |

where is the angle of scattering and is the angle of rotation into the scattering plane.

We designed the MC simulations to mimic the geometry of the polarization-gated probe we have used in previous studies. This probe has overlapping illumination-collection areas of radius 400 µm and a collection angle of .17 The Stokes vectors of each photon packet were tracked and incoherently summed into corresponding bins of radius () giving the response to an input pencil beam. Mueller matrix multiplication was used to obtain the output intensity after a polarizer was oriented at 0 or 90 deg ( or , respectively) with respect to the incident polarization. Convolution was employed to extend the beam from an infinitely narrow source to a circular illumination spot with finite area and radius R. The main objective of this MC study was to determine how the or signals behaved as a function of and . Thus, is varied between 1.1 and 2. is varied between 1.75 and for different anisotropy factors (, 0.8, 0.85, 0.9, 0.93). By recording the signal intensity of the polarization-gated signals as a function of , we developed empirical mathematical relations between the signal intensity, wavelength, and according to Eq. (2).

To confirm that we could depth-selectively recover , we also created a two-layer MC model where the first layer had an and the second layer had an . We then calculated the value from the and signal intensities. As the signal probes a deeper penetration depth than the signal, we expected the signal to be more sensitive to the of the top layer and the signal to be more sensitive to the of the bottom layer. We also varied the thickness of the top layer to ascertain the precise thickness at which the individual ’s could be distinguished by independent analysis of the and signal intensities.

2.3. Determination of Length-Scale Sensitivity of the Measurement

We followed a procedure outlined by Yi et al. to determine the range of length scales that the measurement of is sensitive to.22 The wavelength dependence of the polarization-gated signals is primarily determined by which in turn can be calculated from the index correlation function. Thus to determine the length-scale sensitivity of the measurement we perturbed the index correlation function at different length scales and calculated the corresponding change in . To determine the inner length scale , the index correlation function was truncated at such that . This perturbed index correlation function was then used to calculate . To do this, the spectral density was taken as the Fourier transform of and the differential scattering cross section was calculated as:

| (6) |

Next, the scattering coefficient was computed by integrating the differential scattering section over all angles:

| (7) |

The anisotropy factor is given as the mean cosine of the scattering angle over all directions:

| (8) |

Finally, the reduced scattering coefficient can be calculated as . These calculations were performed for , , , and repeated for different and values. This created a spectrum from which we extracted a measured value. The error between the measured value and the input value was determined as a function of . The inner length scale for which the measurement of is sensitive to was defined as the minimum value for which the error exceeded 5%. An analogous procedure was performed to determine the maximum length scale the measurement is sensitive to. The perturbed index correlation function in this case was:

| (9) |

where is the outer length scale. For , decays at a power of three to reflect the lack of mass-density fluctuation. The maximum length-scale sensitivity was defined as the maximum for which the error exceeded 5%.

2.4. Animal Model

This study utilized the AOM-induced rat carcinogenesis model that we have previously employed to detect morphological alterations associated with field carcinogenesis.15 Animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of NorthShore University HealthSystem and Northwestern University. Twenty-four male Fisher 344-strain rats were housed in NorthShore’s animal research facility and provided with a diet of AIN-76A (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) rodent chow. Animals were housed in polycarbonate, solid-bottomed cages with Alpha-dry bedding which were changed weekly. Each solid-bottom cage was supplemented with an automatic water system and ventilation ports. Each cage housed two rats in a 12-h light/dark cycle animal room at a temperature between 18 and 26ºC with minimal humidity. Animals were monitored for one week prior to injections as an acclimation period for the rodents. Rats were randomized to either a saline or AOM treatment group. At eight weeks of age, 18 rats received two weekly intraperitoneal injections of 15-mg-per-kg-of-bodyweight 13.4-moles/liter AOM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) while the remaining six rats instead received intraperitoneal saline injections to serve as a control group.

2.5. Animal Colonoscopy and Polarization-Gated Spectroscopy Measurements

At 18 and 40 weeks post initial AOM/saline injection, rats underwent colonoscopy and polarization-gated spectroscopy measurement. Animals were fasted overnight prior to colonoscopic procedures. Rats were anaesthetized using the Veta Mac Lab Animal Anesthesia System (Veta Mac, Rossville, IN). Each animal was anaesthetized individually in an anesthesia induction chamber supplemented with (vaporized) 1–3% isoflorane (Piramal Healthcare Limited, Andhra Pradesh, India) and oxygen mixture.

After complete sedation was achieved, the rat was removed from the chamber and placed on its ventral. A nose cone was placed on the animal to continuously deliver isofluorane and maintain sedation. The colon was then lavaged to remove fecal debris by rectal injection of saline (with a ball-point needle and 50-mL syringe). Karl Storz veterinary (straight) endoscope (Storz, Goleta, CA) was inserted into the rectum and the rat colon was visualized on the video screen. The presence of polyps, their size, and their relative location were noted. Representative endoscopic images of a rat with a normal colon and a rat harboring a polyp are shown in Fig. 1(a) and 1(b), respectively. The scope was then removed and a 2.45-mm diameter fiber-optic polarization-gated spectroscopy probe was inserted into the rectum approximately 5 cm into the animal colon. Five measurements were then taken with the probe from the distal colonic mucosa. Probe measurements were taken in areas devoid of polyps as determined by the colonoscopy visualization. The probe and nose cone were then removed and the rat was monitored until effects of anesthetic were no longer noticeable.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic images of a normal saline control (a) and an AOM-treated rat with a tumor (b).

2.6. Polarization-Gated System and Data Analysis

The details of the polarization-gated probe and signal-collection system have been described previously.17 In brief, the probe consists of 3 fibers arranged in an equilateral triangle. One of these fibers delivers a linearly polarized and collimated beam of light onto the tissue surface. The two remaining fibers receive light backscattered from the tissue with one fiber collecting light polarized parallel to the incident beam and the fiber collecting light polarized perpendicular to the incident beam. Each collection fiber is connected to a fiber-optic spectrometer so that the signal intensity can be analyzed as a function of wavelength. The spectrum from each tissue site and both polarization channels was analyzed according to the following relationship:

| (10) |

Where and are the molar extinction spectra due to the presence of oxyhemoglobin (OHb) and deoxyhemoglobin (DHb) within the tissue, is the product of concentration and pathlength, and is a correction factor for the inhomogeneous distribution (packing) of hemoglobin into blood vessels:23–25

| (11) |

where is the average blood-vessel radius and is the absorption coefficient of whole blood. Methods to separate the absorbance spectrum from the scattering spectrum have been further described in detail in previous publications.7,17,26 The precise functional form of was determined using the MC methods described in Secs. 2.1 and 2.2 and is described in the results section. Once the absorbance spectrum is removed from the signal, the value of can be fit to the resultant scattering spectrum using the least-squares minimization technique.

3. Results

3.1. MC-Derived Relationship between Polarization-Gated Signal Intensities and

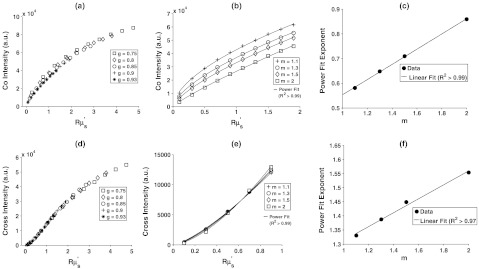

In Fig. 2(a), we plot the signal intensity versus for several different anisotropy factors and . For , the individual curves for different are within 5%, indicating that the signal can be written as a function of rather than a combination of and . In Fig. 2(b), we plot the same signal intensity versus curves but for different and a single anisotropy factor (). These curves clearly show that the value of influences the -signal-intensity-versus--relationship. However, we found that each curve could be fit with a power law such that where the exponent is a function of . The power law fit each of the curves well with an in all cases. The exponent was found to be a linear function of with an as shown in Fig. 2(c). Using the proportionality between and derived from the Whittle-Matern model and the linear fit to , we can express the wavelength dependence of the copolarized signal as:

| (12) |

We repeated this procedure for the crosspolarized signal in Fig. 2(d)–2(f). The intensity-versus- curves overlapped for all ’s as shown in Fig. 2(d) with percentage deviation due to of . In Fig. 2(e), we demonstrate that different values give rise to different crosspolarized-intensity-versus- curves but that each curve can be fit with a power law (). Finally, in Fig. 2(f), we show that the exponent of the power law follows a linear trend with in the same manner that it did for the copolarized signal. Following this analysis, the wavelength dependence of the crosspolarized signal can be written as:

| (13) |

By fitting Eqs. (12) and (13) to the copolarized and crosspolarized signals, the value of can be extracted from polarization-gated measurements.

Fig. 2.

Extraction of the index correlation-function shape () from the copolarized intensity (top row) and crosspolarized intensity (bottom row). (a) For , the intensity is a function of and independent of . A power law can be fit to this dependence for different as shown in (b). The exponent of the power law has a linear relationship with as shown in (c). (d–f) are analogous to (a–c) but for the crosspolarized intensity rather than copolarized intensity.

3.2. Measurement of from a Dual-Layer MC Model

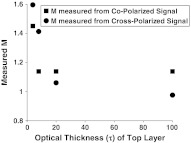

The analysis so far assumes a homogeneous medium defined by a single value. In reality, biological tissue is a layered medium most likely defined by more than a single m. Since the copolarized and crosspolarized signals sample different penetration depths (350 µm and 575 µm on average, respectively), it is likely that the values measured by these individual signals will be different, with the copolarized signal measuring the value of superficial layers of and the crosspolarized signal measuring the value of deeper layers. To test this hypothesis, we created a two-layer MC model in which the top layer had an of 1.1 and the bottom layer an of 1.7. The optical thickness of the first layer, defined as the product of the physical thickness and the scattering coefficient , was varied between 0 and 100 while the overall of the medium was fixed at 1000. Figure 3 shows the values measured from the co- and crosspolarized intensities as a function of the optical thickness of the top layer. When of the top layer is less than , both co- and cross-signals predominantly interrogate the bottom layer (). For greater than , both signals probe the top layer (). For , the copolarized signal probes mainly the top layer and thus is close to 1.1. In contrast, the crosspolarized signal measures the bottom layer and has an value closer to 1.7.

Fig. 3.

Depth-selective extraction of index correlation shape () from a dual-layer Monte Carlo model. The top layer has and bottom layer an of 1.7. The values from the copolarized and crosspolarized signals are recorded as the optical thickness () of the top layer is varied. For , the copolarized parameter is sensitive to the top layer and the crosspolarized parameter is sensitive to the bottom layer.

3.3. Length-Scale Sensitivity of Measurements

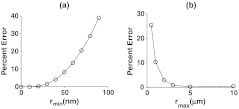

We determined the minimum and maximum length scale over which our spectral determination of is sensitive to by perturbing the index correlation function with different and values as outlined in Sec. 2.3. Figure 4(a) and 4(b) display the percent error between the input value and the measured value from the perturbed index correlation function for different and , respectively. We can define a percent error threshold whereby if the percent error is greater than this threshold for a particular and , then the length scales to which the measurement is sensitive are between and . Defining a threshold of 5% error suggests that the measurement of the value is sensitive to length scales between 45 nm and 1.5 µm according to Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Length-scale sensitivity of index correlation function shape () measurement. (a) Percent between measured and input values after correlation function was truncated at a particular value. (b) Percent error between measured and input values after index correlation function was perturbed at various values according to Eq. (9).

3.4. Tumor Development in Saline/AOM-treated Rats

Rats were assessed at 18 and 40 weeks for tumor development by colonoscopy. The number of rats who had developed tumors by each time point is summarized in Table 1. As expected, none of the saline-treated rats developed tumors over the study time period. 77% of the AOM-treated rats possessed tumors by the end of 40 weeks, with more than half developing tumors by the 18-week time point. This is consistent with earlier studies on tumor development in the AOM-treated rat.27 These results confirm that the saline-treated rats could be reliably regarded as controls and that the AOM treatment was a potent initiator of carcinogenesis.

Table 1.

Number of rats that developed tumors at the 18- and 40- week timepoints.

| Saline-treated | AOM-treated | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 weeks | 40 weeks | Did not develop | 18 weeks | 40 weeks | Did not develop |

| 0 | 0 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 4 |

3.5. Measurement of the Refractive-Index Correlation-Function Shape from Salineand AOM Treated Rats

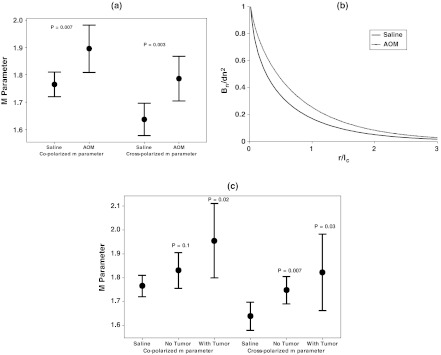

After colonoscopy at the 18-week time point, five polarization-gated probe measurements were taken throughout the visually normal distal mucosa of each saline and AOM-treated rat. For each tissue site, an value was extracted from the copolarized and crosspolarized signals according to Eqs. (7) and (8). The median value from these five sites was taken and used to characterize the mucosa of each individual rat. A Welch’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance between groups. The first comparison we made was between saline-treated rats and all rats treated with AOM. Figure 5(a) shows that in rats treated with AOM, there is a statistically significant increase in the parameter from the visually normal mucosa for both the co- and crosspolarized signals ( and 0.003, respectively). The values for saline controls were and from the co- and crosspolarized signals, respectively, while for AOM they were and from the co- and crosspolarized signals, respectively. Figure 5(b) illustrated what the shape of the refractive-index correlation would look like for saline and AOM-treated rats given the values from the crosspolarized signal. Both curves can be represented by stretched exponentials with the AOM curve decaying more slowly, suggesting that the AOM-rat tissue structure has correlations at longer length scales than the saline-rat tissue structure does. We next investigated whether the parameter could be a predictor of both concurrent and future risk of neoplasia. In Fig. 5(c), we compare the m parameter values measured at 18 weeks among saline controls, AOM rats that developed tumors by 18 weeks (tumor presence), and AOM rats that had not developed tumors by 18 weeks (no tumor presence). This figure demonstrates that the parameter mirrors neoplasia risk. For both the copolarized and crosspolarized parameter, there is an increase in for rats that had not developed tumors by the 18-week time point but were still at risk of developing tumors because of the AOM treatment ( and 0.007, respectively). There is a further increase in in rats that harbored neoplasia at the time of measurement as shown in Fig. 5(b). These results demonstrate that the parameter is most sensitive to the presence of neoplasia, but that it is also predictive of the risk of future neoplastic development.

Fig. 5.

The shape of the index correlation function is sensitive to concurrent and future risk of neoplasia in the AOM-treated rat. (a) Comparison of the values from the copolarized and crosspolarized signals for saline versus all AOM-treated rats shows a statistical significant increase in ( and 0.003). (b). Comparison of the shape of index correlation function shape between saline and AOM-treated rats. (c). Comparison of values between saline controls and AOM-treated rats who had and had not developed tumors at the 18-week measurement point. The value is highest for rats harboring a tumor but is also significant for AOM rats that had not yet developed a tumor. Solid circle points are group means and error bars are 95% CI.

4. Discussion

The results in Sec. 3.4 demonstrate that the parameter measured from the wavelength dependence of the backscattered tissue intensity can demarcate tumor risk in the AOM-rat model. Previous studies have employed light reflectance spectroscopy to document alterations in the spectal slope from tumors compared to normal tissue.28–30 In addition, prior studies from our laboratory on ex vivo samples used elastic light scattering to demonstrate that the spectral slope was a marker of tumor development in the histologically normal mucosa of the AOM rat and human patients.31 It was assumed that the spectral slope was related to the size distribution of scattering structures. In this paper, we have used the Whittle-Matérn correlation function family and Monte-Carlo simulations to formalize the relationship between the wavelength dependence of the signal intensity and the shape of the index correlation function. This allows one to make quantitative comparisons that directly relate to a physical parameter (mass-density distribution) of the tissue structure. It should be noted that our previous ex vivo light-scattering studies showing a decline in spectral slope with precancerous alterations are consistent with our in vivo evidence of an increase in the parameter according to Eqs. (1)–(3).

In Sec. 3.2 we demonstrated that the co- and crosspolarized signals could depth-selectively assess the parameter in a two-layer model given that the optical thickness of the top layer was between approximately 5 and . The thickness of the top layer in the human colon, the mucosa, is on the order of 0.05 cm while the scattering coefficient is about giving an optical thickness of .32,33 In rats, the thickness of the mucosa is ,34 giving an assumed mucosal optical thickness of . Thus, it is possible to depth-selectively quantify the parameter for both animal and human colon tissue under the above assumptions. The importance of depth selectivity for accurate assessment of early cancer risk has been demonstrated by several techniques. Using polarization-gated spectroscopy, we have previously shown that early increases in bloody supply associated with carcinogenesis are more prominent at superficial tissue layers.7,26 Low coherence interferometry has been used to demonstrate that the most significant changes in nuclear diameter in the AOM-treated rat occur at a depth of 35 µm.35 In the present study, both the copolarization and crosspolarization parameter were statistically significant indicators of concurrent neoplasia, suggesting diffuse alterations throughout mucosa and submucosa in the shape of the index correlation function.

The values of identified in this study ranged from 1.6 to 2, with AOM-treated rats having higher values than saline controls. These values of correspond to the index correlation function having the shape of a stretched exponential. Stretched exponential shapes have been observed in alterations associated with ovarian cancer and were linked to scattering objects having similar size.36 The control samples from that study had placing them in the mass fractal regime. Previous studies on rat esophagi also measured control samples to be in the mass fractal regime.13 The precise reason for why our control measurements did not fall into the mass fractal regime is not known, but may have to do with the type of tissue investigated, the depth of the tissue sampled, and the fact that the previous studies mentioned utilized ex vivo biopsies instead of in vivo measurements.

While the results from this study are very promising, there are certain limitations that need to be addressed. The derivation of Eqs. (12) and (13) depends on certain assumptions, the most important being that actual biological tissue conforms to the Whittle-Matérn correlation family. While this correlation family is likely an improvement over functions that treat tissue as discrete scattering particles such as Mie theory, there is a lack of experimental evidence to confirm this. In addition, both the single and dual-layer Monte-Carlo models are simplified models of tissue. In reality, tissue possesses more than two layers and the distribution of optical properties within each layer is not homogeneous. We intend to explore in future studies how modeling a more realistic tissue structure impacts our measurement and interpretation of the index correlation function shape.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we have presented a method for measuring the shape of the tissue refractive-index correlation function from polarization-gated spectroscopy measurements. We have employed this method to measure the function shape in the AOM-treated rat model of colon carcinogenesis and we have found that changes in the shape were correlated with both present and future risk of neoplasia development. Overall, our study provides in vivo evidence from a well-controlled animal model that depth-selective measurements of the index correlation shape can serve as a biomarker for CRC risk assessment, as well as evidence for the field-effect concept in carcinogenesis.

References

- 1.Siegel R., et al. , “Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths,” CA Cancer J. Clin.. 61(4), 212–236 (2011). 10.3322/caac.v61:4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.“Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement,” Ann. Intern. Med. 149(9), 627–637 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rijn J. C., et al. , “Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review,” Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101(2), 343–350 (2006). 10.1111/ajg.2006.101.issue-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy H. K., Backman V., Goldberg M. J., “Colon cancer screening: the good, the bad, and the ugly,” Arch. Intern. Med. 166(20), 2177–2179 (2006). 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imperiale T. F., et al. , “Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population,” N. Engl. J. Med. 351(26), 2704–2714 (2004). 10.1056/NEJMoa033403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis J. D., et al. , “Detection of proximal adenomatous polyps with screening sigmoidoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of screening colonoscopy,” Arch. Intern. Med. 163(4), 413–420 (2003). 10.1001/archinte.163.4.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes A. J., et al. , “Rectal mucosal microvascular blood supply increase is associated with colonic neoplasia,” Clin. Cancer Res. 15(9), 3110–3117 (2009). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy H. K., et al. , “Association between rectal optical signatures and colonic neoplasia: potential applications for screening,” Cancer Res. 69(10), 4476–4483 (2009). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanian H., et al. , “Nanoscale cellular changes in field carcinogenesis detected by partial wave spectroscopy,” Cancer Res. 69(13), 5357–5363 (2009). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh N., Vitkin I. A., “Tissue polarimetry: concepts, challenges, applications, and outlook,” J. Biomed. Opt. 16(11), 110801 (2011). 10.1117/1.3652896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuchin V. V., Wang L. V., Zimnyakov D. A., Optical Polarization in Biomedical Applications, Springer, Berlin: (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baish J. W., Jain R. K., “Fractals and cancer,” Cancer Res. 60(14), 3683–3688 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter M., et al. , “Tissue self-affinity and polarized light scattering in the born approximation: a new model for precancer detection,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 97(13), 138102 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.138102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy H. K., et al. , “Down-regulation of SNAIL suppresses MIN mouse tumorigenesis: modulation of apoptosis, proliferation, and fractal dimension,” Mol. Cancer Ther. 3(9), 1159–1165 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy H. K., et al. , “Four-dimensional elastic light-scattering fingerprints as preneoplastic markers in the rat model of colon carcinogenesis,” Gastroenterology 126(4), 1071–1081 and 1948 (2004). 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barer R., Tkaczyk S., “Refractive index of concentrated protein solutions,” Nature 173(4409), 821–822 (1954). 10.1038/173821b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turzhitsky V. M., et al. , “Measuring mucosal blood supply in vivo with a polarization-gating probe,” Appl. Opt. 47(32), 6046–6057 (2008). 10.1364/AO.47.006046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers J. D., Capoglu I. R., Backman V., “Nonscalar elastic light scattering from continuous random media in the Born approximation,” Opt. Lett. 34(12), 1891–1893 (2009). 10.1364/OL.34.001891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramella-Roman J. C., Prahl S. A., Jacques S. L., “Three Monte Carlo programs of polarized light transport into scattering media: part II,” Opt. Express 13(25), 10392–10405 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.010392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaillon F., Saint-Jalmes H., “Description and time reduction of a Monte Carlo code to simulate propagation of polarized light through scattering media,” Appl. Opt. 42(16), 3290–3296 (2003). 10.1364/AO.42.003290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moscoso M., Keller J. B., Papanicolaou G., “Depolarization and blurring of optical images by biological tissue,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 18(4), 948–960 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi J., et al. , Inverse Scattering Optical Coherence Tomography (ISOCT): Quantifying Sub-Diffractional Tissue Mass Density Correlation Function, PNAS, Northwestern Unviersity, Evanston: (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finlay J. C., Foster T. H., “Effect of pigment packaging on diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of samples containing red blood cells,” Opt. Lett. 29(9), 965–967 (2004). 10.1364/OL.29.000965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svaasand L., et al. , “Therapeutic response during pulsed laser treatment of port-wine stains: dependence on vessel diameter and depth in dermis,” Las. Med. Sci. 10(4), 235–243 (1995). 10.1007/BF02133615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Veen R. L., Verkruysse W., Sterenborg H. J., “Diffuse-reflectance spectroscopy from 500 to 1060 nm by correction for inhomogeneously distributed absorbers,” Opt. Lett. 27(4), 246–248 (2002). 10.1364/OL.27.000246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy H. K., et al. , “Spectroscopic microvascular blood detection from the endoscopically normal colonic mucosa: biomarker for neoplasia risk,” Gastroenterology 135(4), 1069–1078 (2008). 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobaek-Larsen M., et al. , “Review of colorectal cancer and its metastases in rodent models: comparative aspects with those in humans,” Comp. Med. 50(1), 16–26 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mourant J. R., et al. , “Spectroscopic diagnosis of bladder cancer with elastic light scattering,” Laser Surg. Med. 17(4), 350–357 (1995). 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Utzinger U., et al. , “Reflectance spectroscopy for in vivo characterization of ovarian tissue,” Laser Surg. Med. 28(1), 56–66 (2001). 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigio I. J., et al. , “Diagnosis of breast cancer using elastic-scattering spectroscopy: preliminary clinical results,” J. Biomed. Opt. 5(2), 221–228 (2000). 10.1117/1.429990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy H. K., et al. , “Spectral slope from the endoscopically-normal mucosa predicts concurrent colonic neoplasia: a pilot ex vivo clinical study,” Dis. Colon Rectum. 51(9), 1381–1386 (2008). 10.1007/s10350-008-9384-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z., et al. , “Laser-induced autofluorescence microscopy of normal and tumor human colonic tissue,” Int. J. Oncol. 24(1), 59–63 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei H. J., et al. , “Differences in optical properties between healthy and pathological human colon tissues using a Ti:sapphire laser: an in vitro study using the Monte Carlo inversion technique,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10(4), 44022 (2005). 10.1117/1.1990125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma R., et al. , “Rat intestinal mucosal responses to a microbial flora and different diets,” Gut 36(2), 209–214 (1995). 10.1136/gut.36.2.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robles F. E., et al. , “Detection of early colorectal cancer development in the azoxymethane rat carcinogenesis model with Fourier domain low coherence interferometry,” Biomed. Opt. Express 1(2), 736–745 (2010). 10.1364/BOE.1.000736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadiarnykh O. et al. , “Alterations of the extracellular matrix in ovarian cancer studied by Second Harmonic Generation imaging microscopy,” BMC Cancer 10(94) (2010) 10.1186/1471-2407-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]