Abstract

Sickle cell anemia is one of the best studied inherited diseases, and despite being caused by a single point mutation in the HBB gene, multiple pleiotropic effects of the abnormal hemoglobin S production range from vaso-occlusive crisis, stroke, and pulmonary hypertension to osteonecrosis and leg ulcers. Urogenital function is not spared, and although priapism is most frequently remembered, other related clinical manifestations have been described, such as nocturia, enuresis, increased frequence of lower urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, hypogonadism, and testicular infarction. Studies on sickle cell vaso-occlusion and priapism using both in vitro and in vivo models have shed light on the pathogenesis of some of these events. The authors review what is known about the deleterious effects of sickling on the genitourinary tract and how the role of cyclic nucleotides signaling and protein kinases may help understand the pathophysiology underlying these manifestations and develop novel therapies in the setting of urogenital disorders in sickle cell disease.

1. Introduction

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) has been first described over a century ago [1] and has become one of the best studied inherited human diseases. Despite being caused by a single point mutation in the HBB gene, multiple pleiotropic effects of the abnormal hemoglobin S production range from vaso-occlusive crisis, stroke, and pulmonary hypertension to osteonecrosis and leg ulcers [2–4].

Genitourinary tract function is also affected in SCA, and although priapism is most frequently remembered, other related clinical manifestations have been described, such as nocturia, enuresis, increased frequency of lower urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, hypogonadism, and testicular infarction. Sickle hemoglobin S (HbS) polymerizes when deoxygenated, resulting in a series of cellular alterations in red cell morphology and function that shorten the red cell life span and lead to vascular occlusion. Sickle cell disease (SCD) vaso-occlusion constitutes a complex multifactorial process characterized by oxidative stress and recurrent ischemia-reperfusion injury in a vicious circle contributing to reduced blood flow and results, eventually, in complete obstruction of the microcirculation and organic dysfunction [3–6]. The exact pathogenetic mechanisms that tie genitourinary complications to the fundamental event of HbS polymerization and hemolytic anemia in SCA have just about started to be unraveled.

This paper focuses on how previous, sometimes poorly explained, clinical observations of urogenital disorders in patients with SCD relate to more recent discoveries on the role of cyclic nucleotides and protein kinases in the pathophysiology of sickle vaso-occlusion.

2. Priapism

Priapism is defined as a prolonged and persistent penile erection, unassociated with sexual interest or stimulation, and is one of the complications associated with sickle cell anemia (SCA) since early in 1934 [7]. Priapism reaches a frequency of up to 45% in male patients with SCA, and the rate of resulting erectile dysfunction (ED) exceeds 30% [8–10]. Although this complication has been previously reviewed in depth in this journal [11], the main concepts behind its pathophysiology will be summarized here for better understanding of the mechanisms discussed throughout the paper, but readers are encouraged to read the previous review.

According to the American Urological Association Guidelines on the Management of Priapism, priapism can be subdivided into three categories: ischemic, stuttering, and nonischemic. Ischemic priapism (veno-occlusive, low flow) is a persistent erection marked by rigidity of the corpora cavernosa (CC) and little or no cavernous arterial inflow. In ischemic priapism, there are time-dependent changes in the corporal metabolic environment with progressive hypoxia, hypercarbia, and acidosis that typically generate penile pain. Penile sinusoids are regions prone to red blood cell sickling in SCD men because of blood stasis and slow flow rates, and ischemic priapism is thought to result from prolonged blockage of venous outflow by the vaso-occlusive process. Clinically, there is congestion and tenderness in the CC, sparing the glans and corpus spongiosum, usually with a prolonged course of over 3 hours, and frequently resulting in fibrosis and erectile dysfunction. Stuttering priapism (acute, intermittent, recurrent ischemic priapism) is characterized by a pattern of recurrence, but an increasing frequency or duration of stuttering episodes may herald a major ischemic priapism. Nonischemic priapism (arterial, high flow) is a persistent erection caused by unregulated cavernous arterial inflow. Typically, the corpora are tumescent but not rigid, the penis is not painful and is most frequently associated with trauma [12–16].

Conventional treatments are largely symptomatic, usually administered after the episode of priapism has already occurred, because the etiology and mechanisms involved in the development of priapism are poorly characterized [17, 18]. Preventive interventions have been proposed but, without a clear idea of the molecular mechanisms involved, they remain largely impractical to be applied in a regular basis in the clinic [17]. Due to the difficulty in exploring these mechanisms in patients, the use of animal models of priapism has become of utmost importance to decipher this devastating clinical challenge [19]. Animal models for priapism include dogs [20, 21], rabbits [22], rats [23–27], and mice [28–41].

Molecular biology and genetic engineering have been widely used in animal models to explore gene function in both human physiology and in the study of pathology of human priapism. Four major priapism animal models have been developed and have yielded greater knowledge on the intrinsic mechanisms underlying priapism: the intracorporal opiorphins gene transfer rat model [42–45], the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) with or without neuronal NOS (nNOS) knock-out (eNOS−/− ± nNOS−/−) mouse models [28, 29, 31–33], the adenosine deaminase knock-out (Ada−/−) mouse model [35, 36, 40, 41] and the transgenic sickle cell Berkeley mouse model [30, 33, 34, 37–39]. However, the Berkeley mouse is the only well-accepted animal model that displays clinical manifestations similar to those seen in humans with severe forms of SCD, including priapism [30, 34].

Priapism is essentially a derangement of normal erection. Penile erection is a hemodynamic event that is regulated by smooth muscle relaxation/contraction of corpora cavernosa and associated arterioles during sexual stimulation. The penile flaccidity (detumescence state) is mainly maintained by tonic release of norepinephrine through the sympathetic innervations of vascular and cavernosal smooth muscle cells [46]. During penile erection (tumescence state), vascular smooth muscle relaxation decreases vascular resistance, thereby increasing blood flow through cavernous and helicine arteries and filling sinusoids, which are expanded due to the relaxation of smooth muscle cells in the CC [47]. This physiological relaxation of penile smooth muscle is mainly, although not solely, mediated by the neurotransmitter nitric oxide (NO) that is produced by enzymes called NO synthases (NOS). NOSs are subdivided into three isoforms, endothelial NOS (eNOS or NOS3), neural NOS (nNOS or NOS1), and inducible NOS (iNOS or NOS2) [48, 49]. In the penile smooth muscle, NO is released from both nitrergic nerves and the sinusoidal endothelium [46, 50–52]. NO stimulates the soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) in the cavernosal smooth muscle, triggering increased synthesis of cyclic GMP (cGMP) that provides the main signal for smooth muscle relaxation [53]. cGMP levels in the CC are regulated by the rate of synthesis determined by sGC and the rate of cGMP hydrolysis mediated by phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) [54, 55]. It has been reported that plasma hemoglobin released by intravascularly hemolysed sickle erythrocytes consumes NO, reducing its bioavailability in the erectile tissue, skewing the normal balance of smooth muscle tone towards vasoconstriction [17, 56, 57]. Champion and collaborators [33] showed that the penile smooth muscle of SCD transgenic mice presents with dysregulated PDE5A expression activity. Moreover, these mice had spontaneous priapism, amplified CC relaxation response mediated by the NO-cGMP signaling pathway, and increased intracavernosal pressure in vivo [37, 38].

Recent evidence has shown that another signaling pathway that may also contribute to the pathophysiology of priapism in SCD involves adenosine regulation. Similarly to NO, adenosine is a potent vasodilator produced by adenine nucleotide degradation. Adenosine is predominantly generated by adenosine monophosphate (AMP) dephosphorylation catalyzed by intracellular 5′-nucleotidase. Hydrolysis of s-adenosyl-homocysteine also contributes to intracellular adenosine formation [58, 59]. Extracellular adenosine may be generated by both adenine nucleotide degradation and dephosphorylation by ectonucleotidases [60]. Adenosine is then catabolized by two enzymes: adenosine kinase (ADK), which phosphorylates adenosine to AMP and is an important regulator of intracellular adenosine levels; and adenosine deaminase (ADA), which catalyzes the irreversible conversion of adenosine to inosine [58].

Several physiological processes may be affected by extracellular adenosine and this is mediated by four different receptors, referred to as A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. All four subtypes are members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. The activation of the A1 and A3 adenosine receptors inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity and also results in increased activity of phospholipase C, while activation of the A2A and A2B subtypes increases adenylyl cyclase activity [58, 61]. Adenosine-induced vasodilation is mediated by increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels in vascular smooth muscle cells via A2 receptor signaling [62, 63]. cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA) resulting in decreased calcium-calmodulin-dependent MLC phosphorylation and enhanced smooth muscle relaxation [64]. Its role in penile erection has been investigated in studies showing that intracavernous injection of adenosine resulted in tumescence and penile erection [36, 61, 65]. In addition, adenosine induces NO synthesis in endothelial cells through A2 receptor signaling, and adenosine-mediated CC relaxation is partially dependent on endothelium-derived NO [36, 66–70].

A priapic phenotype in Ada−/− mice was identified and led to further investigation of the impact of adenosine in the pathophysiology of priapism [59]. Previous reports showed that high levels of adenosine caused prolonged corporal smooth muscle relaxation in vitro. However, this effect was quickly corrected by intraperitoneal injection of a high dose of polyethylene glycol-ADA (PEG-ADA), which effectively reduces adenosine levels systemically [36, 71]. Moreover, adenosine induced significant increases in cavernosal cAMP levels via A2B receptor activation. This demonstrated that A2B receptor signaling is required for adenosine-mediated stimulation of cAMP production in CC smooth muscle cells [36, 71]. Mi and collaborators [36] have studied adenosine levels in the penis of sickle cell mice and have found a significant increase in adenosine levels, suggesting that overproduction of adenosine may contribute to priapic activity in SCD [71, 72]. Sickle cell mice submitted to PEG-ADA treatment suffered significant reduction of force and duration of relaxation when compared with untreated mice [71]. In addition, increased adenosine levels contributed to the development of penile fibrosis in Ada−/− mice as well as in transgenic sickle cell mice [72]. These findings suggest a general contributory role of elevated adenosine in the pathophysiology of priapism associated with SCD.

Although the penile vascular endothelium and smooth muscle cells are sources of vasodilation factors such as NO and adenosine, there are vasoconstriction pathways important to the penile hemodynamics, such as the Rho-kinase (ROCK) pathway. The RhoA/ROCK signal transduction pathway has been shown to influence erectile function in vivo through an array of mechanisms, including vasoconstriction of the penile vasculature via smooth muscle contraction and regulation of eNOS [73–76]. This pathway is involved in the regulation of smooth muscle tone by modulating the sensitivity of contractile proteins to Ca2+ [77]. RhoA regulates smooth muscle contraction by cycling between a GDP-bound inactive form (coupled to a guanine dissociation inhibitor, RhoGDI) and a GTP-bound active form [78–80]. Upstream activation of heterotrimeric G proteins leads to the exchange of GDP for GTP, an event carried out by the guanine exchange factors (GEFs) p115RhoGEF [81], PDZ-RhoGEF [82], and LARG (Leukemia-associated RhoGEF) [83], which are able to transduce signals from G protein-coupled receptors to RhoA [84–86]. ROCK is activated by RhoA and inhibits myosin phosphatase through the phosphorylation of its myosin-binding subunit, leading to an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity. The RhoA/ROCK Ca2+ sensitization pathway has been implicated in the regulation of penile smooth muscle contraction and tone both in humans and animals [77, 87]. ROCK exerts contractile effects in the penis by Ca2+-independent promotion of myosin light chain (MLC) kinase or the attenuation of MLC phosphatase activity and reduction in endothelial-derived NO production [88]. RhoA activation, ROCK2 protein expression, as well as total ROCK activity decline in penile of SCD transgenic mice, highlighting that the molecular mechanism of priapism in SCD is associated with decreased vasoconstrictor activity in the penis [39]. Therefore, should impaired RhoA/ROCK-mediated vasoconstriction contribute to SCD-associated priapism, this pathway may become a novel therapeutic target in the management of this complication.

There has been no definite advance in the management of sickle cell-associated acute, severe priapism. Penile aspiration with or without saline intracavernosal injection and eventually performing surgical shunts remains mainstays of care, with no evident benefit of more common approaches, such as intravenous hydration, blood transfusions, and urinary alkalinization [89, 90]. Pharmacological interventions in such cases have been limited to intracavernosal use of sympathomimetic drugs, such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, and etilefrine, but there are anecdotal reports of acute use of PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil [91].

Nonetheless, most attempts to control SCD priapism have focused on its recurrent, stuttering form. Small case series of hormonal manipulation with diethylstilbestrol [92], gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues [93], and finasteride [94] have been reported to successfully manage recurrent priapism. Increasing smooth muscle tone with oral α-agonist etilefrine has also yielded only anecdotal evidence of benefit [95]. Unfortunately, a prospective study comparing etilefrine and ephedrine failed to demonstrate superiority or equivalence of both drugs in preventing recurrent priapism due to poor compliance and low recruitment reducing statistical power, but some evidence was obtained reassuring safety of the use of such strategies, and possibly indicating a lower severity of priapism attacks among compliant patients [96]. This favors off-label use of pseudoephedrine at bedtime advocated by some experts [57, 90]. Hydroxyurea has also been effective in preventing priapism recurrence in SCD in a small number of cases [97, 98]. Based on current knowledge of NO-dependent pathways, the use of PDE5 inhibitors has been studied. One clinical trial testing tadalafil in SCD patients has been terminated, but no outcome data have yet been published (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00538564), and one ongoing trial aims at the effect of sildenafil in the same setting (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00940901). Despite these efforts, scientists have become less optimistic concerning the tolerability of this approach, ever since the premature termination of the sildenafil trial for pulmonary hypertension in SCD patients, in which subjects on PDE5 inhibitor were more likely to have severe pain crises requiring hospitalization [99]. Therefore, novel therapies for preventing and treating priapism in SCD are still warranted if the incidence of impotence among these patients is expected to be reduced in the long term.

3. Infertility

Progress in the therapy of SCD, particularly the use of hydroxyurea, has considerably improved the prognosis of patients with SCD [100, 101], with their mean life expectancy reaching much over 40 years [102–104], rendering infertility an important issue. Nevertheless, long before hydroxyurea became a standard of care in SCD, seminal fluid parameters of SCD males had been reported to fall within the subfertile range due to decreased sperm concentration, total count, motility, and altered morphology [105–107], and a more recent study reported over 90% of patients had at least one abnormal sperm parameter [108].

Hydroxyurea (HU) has been reported to impair spermatogenesis, causing testicular atrophy, reversible decrease in sperm count, as well as abnormal sperm morphology and motility [108–114], and its current or previous use should be among the first probable causes to be considered in SCD patients complaining of infertility. Moreover, sperm abnormalities prior to HU have been attributed to variable effects of hypogonadism induced by SCD itself, and lack of appropriate testosterone production seems to be exacerbated by HU use in a mouse SCD model [115].

Considering that male fertility does not rely solely on the quality of the seminal fluid, other causes that may also render male patients with SCD prone to suffer from infertility include sexual problems, such as loss of libido, premature ejaculation, frequent priapism, and priapism-related impotence [105–107, 116–121].

Finding a single main cause for male infertility in a particular SCD patient is highly unlikely and probably will involve some degree of endocrinological impairment. A broader understanding of how hypogonadism takes place in SCD is necessary to explain fertility problems and requires knowledge of the complexity of sex hormone production regulation.

4. Hypogonadism

The etiology of hypogonadism in SCD patients is multifactorial, as several mechanisms have been suggested to contribute to its occurrence, such as primary gonadal failure [117, 122, 123], associated with or caused by repeated testicular infarction [124], zinc deficiency [125, 126], and partial hypothalamic hypogonadism [127].

Physical and sexual development are affected in both male and female SCD patients, with onset of puberty (menarche) and appearance of secondary sexual characteristics (pubic and axillary hair and beard) being usually delayed. The delay is greater in homozygous SCA and S-β 0-thalassemia than in SC disease and S-β +-thalassemia [128–130]. Moreover, studies in male patients with SCD reported reduction of ejaculate volume, spermatozoa count, motility, and abnormal sperm morphology [106, 116].

Biochemical analyses have demonstrated low levels of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone and variable levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) in patients with SCD [105–107, 118, 119, 121, 131]. The comparison between patients and controls matched according to stage of development of secondary sexual characteristics showed higher levels of LH in sickle cell disease, favoring some role for hypergonadotropic hypogonadism.

Leydig cells of the testes and other steroidogenic tissues produce hormones by a multienzymatic process, in which free cholesterol from intracellular stores is transferred to the outer and then to the inner mitochondrial membrane. Leydig cells produce androgens under the control of LH or its placental counterpart human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), as well as in response to numerous intratesticular factors [114, 132]. LH/hCG receptors belong to the sGC-coupled seven-transmembrane-domain receptor family, whose activation leads to stimulation of adenylyl cyclase [133]. The resulting accumulation of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and the concomitant activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) lead to the phosphorylation of numerous proteins, including the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein [134, 135]. StAR localizes predominantly to steroid hormone-producing tissues and consists of a 37 kDa precursor containing an NH2-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence and several isoelectric 30 kDa mature protein forms [136–138]. Steroid production in gonadal and adrenal cells requires both de novo synthesis and PKA-dependent phosphorylation of StAR-37 protein [139]. The newly synthesized StAR is functional and plays a critical role in the transfer of cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane, whereas mitochondrial import and processing to 30 kDa StAR protein terminate this action [140–142].

HbS polymerization is mediated by upstream activation of adenosine receptor A2BR by hypoxia, and hemolysis of irreversibly sickled red blood cells increases adenosine bioavailability through conversion of ATP by ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73, thus predisposing patients with SCD to sustained high levels of cAMP [143, 144]. From this point of view, steroidogenesis could be expected to be increased in these patients.

Although Leydig cell steroidogenesis is predominantly regulated by cAMP/PKA, other pathways also influence this process [145], including the NO-cGMP signaling pathway [146]. NO promotes a biphasic modulation in the androgen production, stimulatory at low concentrations, and inhibitory at high concentrations [49, 147, 148]. SCA causes NO depletion, and in low levels, NO stimulates Leydig cell steroidogenesis by activating sGC [48, 49, 149] and promotes the formation of low levels of cGMP, albeit enough to activate the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) and phosphorylate StAR [49, 150]. This signaling is controlled by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) [151] and active transport systems that export cyclic nucleotides (multidrug-resistance proteins) from the cell [152]. In zona glomerulosa cells, activation of PKG II by cGMP regulates basal levels of aldosterone production and phosphorylation of StAR protein [150], but whether there is a role for cGMP in the zona reticularis, where adrenal androgenesis takes place, is unknown.

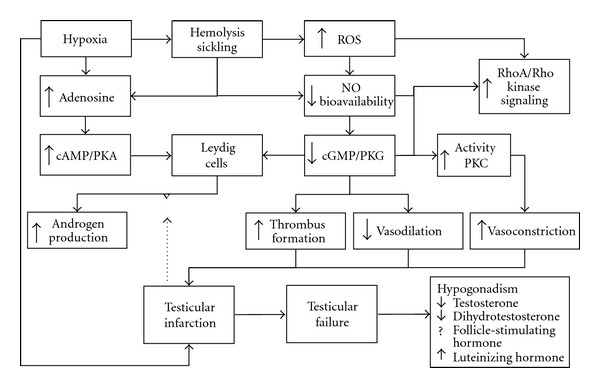

Hypogonadism observed in patients with SCD with lower circulating testosterone and higher LH levels suggests that, at least in this setting, despite the reduced cGMP- and elevated cAMP-mediated stimuli on androgen production, gonadal failure with Leydig cell impairment predominates in sex hormone production dysfunction (Figure 1). This further highlights that primary hypogonadism is possibly largely underdiagnosed and elicits more studies on the pathogenesis of testicular infarction.

Figure 1.

Schematic pathophysiology of hypogonadism and testicular infarction in sickle cell disease. The dashed arrow represents the blocking effect of gonadal failure over cyclic nucleotide-stimulated androgen production.

5. Testicular Infarction

Segmental testicular infarction is an infrequent cause of acute scrotum and is rarely reported, with fewer than 40 cases published at the time of this paper. Its etiology is not always well defined, and it may be, at first, clinically mistaken for a testicular tumour [153, 154]. Common causes for testicular infarction are torsion of the spermatic cord, incarcerated hernia, infection, trauma, and vasculitis [131]. The usual presentation is a painful testicular mass unresponsive to antibiotics [155]. This testicular disorder has been associated with epididymitis, hypersensitivity angiitis, intimal fibroplasia of the spermatic cord arteries, polycythemia, anticoagulant use, benign testicular tumors and, in the interest of this review, sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease [124, 131, 155–158].

Testicular infarction related to sickling has been very rarely reported with only five individual cases found retrospectively, three associated with sickle cell disease and two with sickle cell trait [124, 155–157, 159]. Holmes and Kane reported the first testicular infarction in a patient with SCD who presented with testicular swelling unresponsive to antibiotics. Physical examination revealed that a lesion suspicious for malignancy and ultrasonography demonstrated a hyperechoic mass with an anechoid rim and normal blood flow in the surrounding parenchyma. Radical orchiectomy revealed hemorrhagic infarction with sickle blood red cells. In another case report, SCA patient presented with acute scrotum and history of acute chest syndrome, splenic infarction, osteomyelitis, and hemolysis. Physical examination demonstrated an erythematous, tender, swollen testicle and ultrasound once again revealed normal echotexture and blood flow. Surgical exploration and pathological examination diagnosed segmental testicular infarction with vascular congestion and sickled red blood cells [124]. In the last testicular infarction case report in a patient with SCD presented with increased testicular volume, scrotal ultrasonography showed both echogenic and hypoechogenic regions and Doppler ultrasonography revealed vascular changes compatible with testicular infarction. Radical orchiectomy was performed 10 days after the initial presentation and microscopic evaluation showed necrotic seminiferous tubules devoid of nuclear debris, congestion, or acute inflammatory infiltrate, consistent with coagulative necrosis of ischemic origin [131].

Testicular blood flow is dependent on the internal spermatic, cremasteric, and deferential arteries. Obstruction of venous outflow may create venous thrombosis, testicular engorgement, and subsequent hemorrhagic infarction. In SCD, low oxygen tensions in erythrocytes lead to sickling cells that lose pliability in the microcirculation. Consequently, capillary flow becomes obstructed, worsening local tissue hypoxia, perpetuating the cycle of sickling, and promoting testicular infarction [124, 131, 157].

The cyclic nucleotides and protein kinases may play an important role in the pathophysiology of testicular infarction in SCD. Enhanced hemolysis and oxidative stress contribute to a reduction in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability due to NO scavenging by free hemoglobin and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [160, 161]. As mentioned before, testicular NO signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis [48, 49, 147–149, 162–164] but may also influence testicular circulation. We suggest that the reduction of NO bioavailability and consequent reduction of GMPc levels and of activity of PKG may decrease the vasodilation process in the testes. Moreover, reduced NO levels in patients with sickle cell disease contribute to the development of thrombus formation in the vascular system and could further enhance local ischemia [165, 166]. Furthermore, the cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway would normally inhibit RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization, RhoA/ROCK signaling, and protein kinase C (PKC) activity that mediate contraction in vascular smooth muscle [167–171]. Thus, reduced NO levels may decrease cGMP-dependent protein kinase activity and promote increasing RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization and PKC activity, favoring vasoconstriction in the testes. Therefore, tissue hypoxia, sickling of red blood cells, reduced levels of NO, possible thrombus formation, increased RhoA-induced Ca2+ sensitization, and PKC activity may all lead to capillary and venous flow obstruction promoting testicular infarction (Figure 1).

Although testicular infarction in SCD has been very rarely reported, it has been speculated that silent testicular infarctions are much more common but generally overlooked clinically. Testicular biopsy in patients is rarely performed and additional studies are necessary to establish the true incidence of testicular infarction in patients with SCD or even sickle cell trait.

6. Urinary Bladder Dysfunction

The urinary bladder has two important functions: urine storage and emptying. Urine storage occurs at low pressure, implying that the bladder relaxes during the filling phase. Disturbances of the storage function may result in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs), such as urgency, increased frequency, and urge incontinence, the components of the hypoactive or overactive bladder syndromes [172, 173]. The passive phase of bladder filling allows an increase in volume at a low intravesical pressure. The bladder neck and urethra remain in a tonic state to prevent leakage, thus maintaining urinary continence. Bladder emptying is accompanied by a reversal of function in which detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) contraction predominates in the bladder body that is accompanied by a concomitant reduction in outlet resistance of the bladder neck and urethra [174–176]. The bladder filling and emptying are regulated by interactions of norepinephrine (sympathetic component released by hypogastric nerve stimulation), acetylcholine and ATP (parasympathetic components released by pelvic nerve stimulation) with activation of adrenergic, muscarinic, and purinergic receptors, respectively [175].

Urinary bladder dysfunction is rarely spontaneously reported by SCD patients to their caregivers. With increasing survival of these patients, physicians may expect that urinary complaints increase in association with classical urological disorders associated with advanced age, such as urinary stress incontinence in multiparous women and benign prostatic hyperplasia in men. Nonetheless, clinical observations of medical complaints involving the urinary bladder start as early as childhood, with enuresis, and continue onto adulthood with nocturia and urinary tract infections, to name a few, although frequently neglected.

Nocturia has long been attributed to constant increased urinary volumes in SCD. As part of the renal complications of sickling, renal medullary infarcts lead to decreased ability to concentrate urine, yielding higher daily urinary volumes [177], compensatory polydipsia, and eventually, the need for nocturnal bladder voiding.

For comparison, the effects of polyuria on bladder function have been better characterized in diabetic bladder dysfunction (DBD). Both SCD and diabetes mellitus cause increased urinary volume and, to some extent, the two diseases involve cellular damage by oxidative stress mediators; so data from previous studies on DBD may help shed some light on preliminary data on bladder function in SCD animal models by understanding a known model of bladder dysfunction.

It has been suggested that DBD comprehends so-called early and late phases of the disease, owing to cumulative effects of initial polyuria secondary to hyperglycemia, complicated by oxidative stress influence on the urothelium and nervous damage in the long term of the natural history of diabetes mellitus. In the early phase of DBD, the bladder is hyperactive, leading to LUTS comprised mainly by nocturia and urge incontinence. Later in the course of the disease, the detrusor smooth muscle becomes atonic, abnormally distended, and incontinence is mainly by overflow associated with a poor control of urethral sphincters, and voiding problems take over [178].

DSM physiology also involves cyclic nucleotides and activation of protein kinases. DSM contractions are a consequence of cholinergic-mediated contractions and decreased β-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxations [179]. DSM contains a heterogeneous population of muscarinic receptor subtypes [180, 181], with a predominance of the M2 subtype and a smaller population of M3 receptors. However, functional studies showed that M3 receptors are responsible for promotion of contraction in the DSM of several animal models [182–185] and in humans [186, 187]. Activation of M3 muscarinic receptors in the DSM promotes stimulation of phospholipase C, activates PKC, and increases formation of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) to release calcium from intracellular stores, leading to DSM contraction [87]. Moreover, activation of M2 receptors also induces a DSM contraction indirectly by inhibiting the production of cAMP, reducing PKA activity, and reversing the relaxation induced by β-adrenoceptors [179]. Hence, both mechanisms promote urinary bladder emptying.

There is evidence that the Ca2+-independent RhoA/ROCK pathway is involved in the regulation of smooth muscle tone by altering the sensitivity of contractile proteins to Ca2+ [77]. This pathway has been shown to influence erectile function in vivo through an array of mechanisms, including phosphorylation of the myosin-binding subunit of MLC phosphatase, resulting in increased myosin phosphorylation. RhoA, a member of the Ras (Rat Sarcoma) low molecular weight of GTP-binding proteins, mediates agonist-induced activation of ROCK. The exchange of GDP for GTP on RhoA and translocation of RhoA from the cytosol to the membrane are markers of its activation and enable the downstream stimulation of various effectors such as ROCK, protein kinase N, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and tyrosine phosphorylation [77]. The RhoA/ROCK Ca2+ sensitization pathway has been implicated in the regulation of bladder smooth muscle contraction and tone in humans and animals [77, 188–191]. Thus, alterations in the contraction or relaxation mechanisms of DSM during the filling and emptying phases may contribute to urinary bladder dysfunction. Patients with SCD have not been evaluated for bladder dysfunction in a systematic manner, but preliminary data have shown that Berkeley mice (homozygous SS) exhibit hypocontractile DSM ex vivo, due to a significant decrease of contractile responses to muscarinic agonist carbachol and electrical field stimulation [192]. This bladder dysfunction may contribute to the increased risk of urinary tract infections observed in SCD patients.

In an epidemiological study of 321 children with SCD, 7% had a documented urinary tract infection (UTI), one-third had recurrent infections, and two-thirds had had a febrile UTI [193]. As in normal children, there was a strong predominance of females, and gram-negative organisms, particularly Escherichia coli, were usually cultured. Most episodes of gram-negative septicemia in SCD are secondary to UTI [194]. Moreover, UTIs are more frequent during pregnancy in women with SCA or sickle cell trait [195–197]. The prevalence of UTI in women with SCA is nearly twofold that of unaffected black American women. This association appears to be directly related to HbS levels, since patients with sickle trait have an increased prevalence of bacteriuria, but to a lesser degree than those with SCA. More recently, a study detected that a group of SCD children and adolescents had more symptoms of overactive bladder than a control group [198]. This could be a first documentation of a clinically evident of an early phase of sickle cell bladder dysfunction, but whether there is a late, hypotonic bladder phase in older sickle cell adults remains to be demonstrated.

The presence of increased intracavernosal pressure associated with the amplified corpus cavernosum relaxation response (priapism) mediated by NO-cGMP signaling pathway, the lack of RhoA/ROCK-mediated vasoconstriction in sickle cell transgenic Berkeley mice, and the association of priapism with genitourinary infections and urinary retention further suggest the possibility that changes in the DSM reactivity may contribute to urogenital complications in SCD [36, 38–40, 192]. Despite advances in the understanding of urogenital disorders in the SCD, further studies should clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie genitourinary manifestations of SCD.

7. Conclusions

Urogenital disorders in SCD are the result of pleotropic effects of the production of the abnormal sickling hemoglobin S. While priapism still stands out as the most frequently encountered, current knowledge of the effects of cyclic nucleotide production and activation of protein kinases allows to suspect underdiagnosis of bladder dysfunction and hypogonadism secondary to testicular failure. Moreover, despite our growing understanding of these complications, adequate, efficacious, and well-tolerated treatments are still unavailable, and male patients continue to suffer from infertility and erectile dysfunction. Further work in, both clinical assessments and experimental studies in this field are promising and should help increase physicians' awareness of the importance of more accurate diagnoses, design improved therapeutic strategies, and eventually, achieve better quality of life for SCD patients.

Abbreviations

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- NO:

Nitric oxide

- cAMP:

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- PKA:

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase

- cGMP:

Cyclic Guanosine monophosphate;

- PKG:

Cyclic Guanosine monophosphate protein kinase;

- PKC:

Protein kinase C.

References

- 1.Herrick CJ. The evolution of intelligence and its organs. Science. 1910;31(784):7–18. doi: 10.1126/science.31.784.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg MH. Management of sickle cell disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(13):1021–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato GJ, Gladwin MT. Evolution of novel small-molecule therapeutics targeting sickle cell vasculopathy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(22):2638–2646. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conran N, Franco-Penteado CF, Costa FF. Newer aspects of the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease vaso-occlusion. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(1):1–16. doi: 10.1080/03630260802625709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebbel RP, Boogaerts MAB, Eaton JW, Steinberg MH. Erythrocyte adherence to endothelium in sickle-cell anemia. A possible determinant of disease severity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;302(18):992–995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis RB, Jr., Johnson CS. Vascular occlusion in sickle cell disease: current concepts and unanswered questions. Blood. 1991;77(7):1405–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diggs LW, Ching RE. Pathology of sickle cell anemia. Southern Medical Journal. 1934;27:839–845. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adeyoju AB, Olujohungbe ABK, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications—an international multicentre study. BJU International. 2002;90(9):898–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolan VG, Wyszynski DF, Farrer LA, Steinberg MH. Hemolysis-associated priapism in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2005;106(9):3264–3267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bivalacqua TJ, Burnett AL. Priapism: new concepts in the pathophysiology and new treatment strategies. Current Urology Reports. 2006;7(6):497–502. doi: 10.1007/s11934-006-0061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crane GM, Bennett NE., Jr. Priapism in sickle cell anemia: emerging mechanistic understanding and better preventative strategies. Anemia. 2011;2011:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/297364. Article ID 297364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Foundation for Urologic Disease. Thought leader panel on evaluation and treatment of priapism. Report of the American Foundation for Urologic Disease (AFUD) thought leader panel for evaluation and treatment of priapism. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2001;15(supplement):S39–S43. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Numan F, Cantasdemir M, Ozbayrak M, et al. Posttraumatic nonischemic priapism treated with autologous blood clot embolization. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(1):173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: an etiology for idiopathic priapism? Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(1):237–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finley DS. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency associated stuttering priapism: report of a case. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(12):2963–2966. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin YC, Gam SC, Jung JH, Hyun JS, Chang KC, Hyun JS. Expression and activity of heme oxygenase-1 in artificially induced low-flow priapism in rat penile tissues. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(8):1876–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett AL. Pathophysiology of priapism: dysregulatory erection physiology thesis. Journal of Urology. 2003;170(1):26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000046303.22757.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Kutlu O, Burnett AL. New insights into the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease-associated priapism. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;9:79–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong Q, Deng S, Wang R, Yuan J. In vitro and in vivo animal models in priapism research. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8(2):347–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen KK, Chan JY, Chang LS, Chen MT, Chan SH. Intracavernous pressure as an experimental index in a rat model for the evaluation of penile erection. Journal of Urology. 1992;147(4):1124–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ul-Hasan M, El-Sakka AI, Lee C, Yen TS, Dahiya R, Lue TF. Expression of TGF-beta-1 mRNA and ultrastructural alterations in pharmacologically induced prolonged penile erection in a canine model. The Journal of Urology. 1998;160(6):2263–2266. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812010-00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munarriz R, Park K, Huang YH, et al. Reperfusion of ischemic corporal tissue: physiologic and biochemical changes in an animal model of ischemic priapism. Urology. 2003;62(4):760–764. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evliyaoglu Y, Kayrin L, Kaya B. Effect of allopurinol on lipid peroxidation induced in corporeal tissue by veno-occlusive priapism in a rat model. British Journal of Urology. 1997;80(3):476–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evliyaoğlu Y, Kayrin L, Kaya B. Effect of pentoxifylline on veno-occlusive priapism-induced corporeal tissule lipid peroxidation in a rat model. Urological Research. 1997;25(2):143–147. doi: 10.1007/BF01037931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanli O, Armagan A, Kandirali E, et al. TGF-β1 neutralizing antibodies decrease the fibrotic effects of ischemic priapism. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2004;16(6):492–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin YC, Gam SC, Jung JH, Hyun JS, Chang KC, Hyun JS. Expression and activity of heme oxygenase-1 in artificially induced low-flow priapism in rat penile tissues. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5(8):1876–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uluocak N, AtIlgan D, Erdemir F, et al. An animal model of ischemic priapism and the effects of melatonin on antioxidant enzymes and oxidative injury parameters in rat penis. International Urology and Nephrology. 2010;42(4):889–895. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9706-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang PL, Dawson TM, Bredt DS, Snyder SH, Fishman MC. Targeted disruption of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene. Cell. 1993;75(7):1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90615-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, et al. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377(6546):239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pászty C, Brion CM, Manci E, et al. Transgenic knockout mice with exclusively human sickle hemoglobin and sickle cell disease. Science. 1997;278(5339):876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang PL. Lessons learned from nitric oxide synthase knockout animals. Seminars in Perinatology. 2000;24(1):87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(00)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barouch LA, Harrison RW, Skaf MW, et al. Nitric oxide regulates the heart by spatial confinement of nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Nature. 2002;416(6878):337–340. doi: 10.1038/416337a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, Takimoto E, Kass DA, Burnett AL. Phosphodiesterase-5A dysregulation in penile erectile tissue is a mechanism of priapism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(5):1661–1666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407183102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu. Hemolysis in sickle cell mice causes pulmonary hypertension due to global impairment in nitric oxide bioavailability. Blood. 2007;109(7):3088–3098. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan JH, Chunn JL, Mi TJ, et al. Adenosine deaminase knockout in mice induces priapism via A2b receptor. Journal of Urology. 2007;177, supplement:p. 227. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mi T, Abbasi S, Zhang H, et al. Excess adenosine in murine penile erectile tissues contributes to priapism via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(4):1491–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI33467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bivalacqua TJ, Musicki B, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT, Burnett AL, Champion HC. Establishment of a transgenic sickle-cell mouse model to study the pathophysiology of priapism. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(9):2494–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claudino MA, Franco-penteado CF, Corat MAF, et al. Increased cavernosal relaxations in sickle cell mice priapism are associated with alterations in the NO-cGMP signaling pathway. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(8):2187–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bivalacqua TJ, Ross AE, Strong TD, et al. Attenuated rhoA/rho-kinase signaling in penis of transgenic sickle cell mice. Urology. 2010;76(2):510.e7–510.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, et al. Adenosine deaminase enzyme therapy prevents and reverses the heightened cavernosal relaxation in priapism. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(9):3011–3022. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, et al. Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(3):740–749. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong Y, Tar M, Davelman F, Christ G, Melman A, Davies KP. Variable coding sequence protein A1 as a marker for erectile dysfunction. BJU International. 2006;98(2):396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong Y, Tar M, Monrose V, DiSanto M, Melman A, Davies KP. hSMR3A as a marker for patients with erectile dysfunction. Journal of Urology. 2007;178(1):338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong Y, Tar M, Melman A, Davies K. The opiorphin gene (ProL1) and its homologues function in erectile physiology. BJU International. 2008;102(6):736–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanika ND, Tar M, Tong Y, Kuppam DSR, Melman A, Davies KP. The mechanism of opiorphin-induced experimental priapism in rats involves activation of the polyamine synthetic pathway. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;297(4):C916–C927. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00656.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson KE. Pharmacology of penile erection. Pharmacological Reviews. 2001;53(3):417–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phatarpekar PV, Wen J, Xia Y. Role of adenosine signaling in penile erection and erectile disorders. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(11):3553–3564. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davidoff MS, Middendorff R, Mayer B, DeVente J, Koesling D, Holstein AF. Nitric oxide/cGMP pathway components in the Leydig cells of the human testis. Cell and Tissue Research. 1997;287(1):161–170. doi: 10.1007/s004410050742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andric SA, Janjic MM, Stojkov NJ, Kostic TS. Protein kinase G-mediated stimulation of basal Leydig cell steroidogenesis. American Journal of Physiology. 2007;293(5):E1399–E1408. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00482.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burnett AL, Lowenstein CJ, Bredt DS, Chang TSK, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic mediator of penile erection. Science. 1992;257(5068):401–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersson KE, Wagner G. Physiology of penile erection. Physiological Reviews. 1995;75(1):191–236. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1802–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, et al. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52(3):375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boolell M, Allen MJ, Ballard SA, et al. Sildenafil: an orally active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. International Journal of Impotence Research. 1996;8(2):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gopal VK, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Allosteric sites of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5). A potential role in negative feedback regulation of cGMP signaling in corpus cavernosum. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268(11):3304–3312. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohene-Frempong K, Steinberg MH. Clinical aspects of sickle cell anemia in adults and children. In: Steinberg MH, Forget BG, Higgs DR, Nagel RL, editors. Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology and Clinical Management. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 611–670. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers ZR. Priapism in sickle cell disease. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2005;19:917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2001;53(4):527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phatarpekar PV, Wen J, Xia Y. Role of adenosine signaling in penile erection and erectile disorders. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(11):3553–3564. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2(2):351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tostes RC, Giachini FRC, Carneiro FS, Leite R, Inscho EW, Webb RC. Determination of adenosine effects and adenosine receptors in murine corpus cavernosum. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;322(2):678–685. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.122705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olsson RA, Pearson JD. Cardiovascular purinoceptors. Physiological Reviews. 1990;70(3):761–845. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tager AM, LaCamera P, Shea BS, et al. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 links pulmonary fibrosis to lung injury by mediating fibroblast recruitment and vascular leak. Nature Medicine. 2008;14(1):45–54. doi: 10.1038/nm1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin CS, Lin G, Lue TF. Cyclic nucleotide signaling in cavernous smooth muscle. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2005;2(4):478–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prieto D. Physiological regulation of penile arteries and veins. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2008;20(1):17–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vials A, Burnstock G. A2-purinoceptor-mediated relaxation in the guinea-pig coronary vasculature: a role for nitric oxide. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109(2):424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sobrevia L, Yudilevich DL, Mann GE. Activation of A2-purinoceptors by adenosine stimulates L-arginine transport (system y+) and nitric oxide synthesis in human fetal endothelial cells. Journal of Physiology. 1997;499(1):135–140. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li JM, Fenton RA, Wheeler HB, et al. Adenosine A2a receptors increase arterial endothelial cell nritric oxide. Journal of Surgical Research. 1998;80(2):357–364. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chiang PH, Wu SN, Tsai EM, et al. Adenosine modulation of neurotransmission in penile erection. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1994;38(4):357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faria M, Magalhães-Cardoso T, Lafuente-De-Carvalho JM, Correia-De-Sá P. Corpus cavernosum from men with vasculogenic impotence is partially resistant to adenosine relaxation due to endothelial A2B receptor dysfunction. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006;319(1):405–413. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dai Y, Zhang Y, Phatarpekar P, et al. Adenosine signaling, priapism and novel therapies. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(3, supplement):292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, et al. Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(3):740–749. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Clinton Webb R, et al. Antagonism of Rho-kinase stimulates rat penile erection via a nitric oxide-independent pathway. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(1):119–122. doi: 10.1038/83258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mills TM, Chitaley K, Wingard CJ, Lewis RW, Webb RC. Effect of rho-kinase inhibition on vasoconstriction in the penile circulation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;91(3):1269–1273. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Usta MF, et al. RhoA/Rho-kinase suppresses endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the penis: a mechanism for diabetes-associated erectile dysfunction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(24):9121–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400520101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Musicki B, Ross AE, Champion HC, Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Posttranslational modification of constitutive nitric oxide synthase in the penis. Journal of Andrology. 2009;30(4):352–362. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83(4):1325–1358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Rho/Rho-kinase mediated signaling in physiology and pathophysiology. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2002;80(10):629–638. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riento K, Ridley AJ. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(6):446–456. doi: 10.1038/nrm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhattacharya M, Babwah AV, Ferguson SSG. Small GTP-binding protein-coupled receptors. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2004;32(6):1040–1044. doi: 10.1042/BST0321040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hart MJ, Sharma S, Elmasry N, et al. Identification of a novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the Rho GTPase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(41):25452–25458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukuhara S, Murga C, Zohar M, Igishi T, Gutkind JS. A novel PDZ domain containing guanine nucleotide exchange factor links heterotrimeric G proteins to Rho. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(9):5868–5879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kourlas PJ, Strout MP, Becknell B, et al. Identification of a gene at 11q23 encoding a guanine nucleotide exchange factor: evidence for its fusion with MLL in acute myeloid leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(5):2145–2150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G Protein Signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fukuharaa S, Chikumi H, Silvio Gutkind J. RGS-containing RhoGEFs: the missing link between transforming G proteins and Rho? Oncogene. 2001;20(13):1661–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidt A, Hall A. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: turning on the switch. Genes and Development. 2002;16(13):1587–1609. doi: 10.1101/gad.1003302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Teixeira CE, Priviero FBM, Webb RC. Effects of 5-cyclopropyl-2-[1-(2-fluoro-benzyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine- 3-yl]pyrimidin-4-ylamine (BAY 41-2272) on smooth muscle tone, soluble guanylyl cyclase activity, and NADPH oxidase activity/expression in corpus cavernosum from wild-type, neuronal, and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase null mice. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2007;322(3):1093–1102. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Somlyo AV. New roads leading to Ca2+ sensitization. Circulation Research. 2002;91(2):83–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000028341.63905.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mantadakis E, Ewalt DH, Cavender JD, Rogers ZR, Buchanan GR. Outpatient penile aspiration and epinephrine irrigation for young patients with sickle cell anemia and prolonged priapism. Blood. 2000;95(1):78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kato GJ. Priapism in sickle-cell disease: a hematologist's perspective. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9(1):70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bialecki ES, Bridges KR. Sildenafil relieves priapism in patients with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Medicine. 2002;113(3):p. 252. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Serjeant GR, de Ceulaer K, Maude GH. Stilboestrol and stuttering priapism in homozygous sickle-cell disease. The Lancet. 1985;2(8467):1274–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levine LA, Guss SP. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in the treatment of sickle cell anemia-associated priapism. Journal of Urology. 1993;150(2):475–477. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rachid-Filho D, Cavalcanti AG, Favorito LA, Costa WS, Sampaio FJB. Treatment of recurrent priapism in sickle cell anemia with finasteride: a new approach. Urology. 2009;74(5):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Okpala I, Westerdale N, Jegede T, Cheung B. Etilefrine for the prevention of priapism in adult sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;118(3):918–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seftel AD. A prospective diary study of stuttering priapism in adolescents and young men with sickle cell anemia: report of an international randomized control trial; The priapism in sickle cell study (PISCES study) Journal of Urology. 2011;185(5):1837–1838. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(11)60219-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Saad STO, Lajolo C, Gilli S, et al. Follow-up of sickle cell disease patients with priapism treated by hydroxyurea. American Journal of Hematology. 2004;77(1):45–49. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hassan A, Jam’a A, Al Dabbous IA. Hydroxyurea in the treatment of sickle cell associated priapism. Journal of Urology. 1998;159(5):p. 1642. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199805000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Machado RF, Barst RJ, Yovetich NA, et al. Hospitalization for pain in patients with sickle cell disease treated with sildenafil for elevated TRV and low exercise capacity. Blood. 2011;118(4):855–864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-306167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in Sickle cell anemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332(20):1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bakanay SM, Dainer E, Clair B, et al. Mortality in sickle cell patients on hydroxyurea therapy. Blood. 2005;105(2):545–547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease—life expectancy and risk factors for early death. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Powars DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine. 2005;84(6):363–376. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000189089.45003.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fitzhugh CD, Lauder N, Jonassaint JC, et al. Cardiopulmonary complications leading to premature deaths in adult patients with sickle cell disease. American Journal of Hematology. 2010;85(1):36–40. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nahoum CRD, Fontes EA, Freire FR. Semen analysis in sickle cell disease. Andrologia. 1980;12(6):542–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1980.tb01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Osegbe DN, Akinyanju O, Amaku EO. Fertility in males with sickle cell disease. The Lancet. 1981;2(8241):275–276. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Agbaraji VO, Scott RB, Leto S, Kingslow LW. Fertility studies in sickle cell disease: semen analysis in adult male patients. International Journal of Fertility. 1988;33(5):347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Berthaut I, Guignedoux G, Kirsch-Noir F, et al. Influence of sickle cell disease and treatment with hydroxyurea on sperm parameters and fertility of human males. Haematologica. 2008;93(7):988–993. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lu CC, Meistrich ML. Cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on mouse testis cells. Cancer Research. 1979;39(9):3575–3582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ficsor G, Ginsberg LC. The effect of hydroxyurea and mitomycin C on sperm motility in mice. Mutation Research. 1980;70(3):383–387. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Singh H, Taylor C. Effects of Thio-TEPA and hydroxyurea on sperm production in Lakeview hamsters. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 1981;8(1-2):307–316. doi: 10.1080/15287398109530071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Evenson DP, Jost LK. Hydroxyurea exposure alters mouse testicular kinetics and sperm chromatin structure. Cell Proliferation. 1993;26(2):147–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1993.tb00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wiger R, Hongslo JK, Evenson DP, De Angelis P, Schwarze PE, Holme JA. Effects of acetaminophen and hydroxyurea on spermatogenesis and sperm chromatin structure in laboratory mice. Reproductive Toxicology. 1995;9(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(94)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Saez JM. Leydig cells: endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine regulation. Endocrine Reviews. 1994;15(5):574–626. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-5-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jones KM, Niaz MS, Brooks CM, et al. Adverse effects of a clinically relevant dose of hydroxyurea used for the treatment of sickle cell disease on male fertility endpoints. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6(3):1124–1144. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6031124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Friedman G, Freeman R, Bookchin R. Testicular function in sickel cell disease. Fertility and Sterility. 1974;25(12):1018–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)40809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abbasi AA, Prasad AS, Ortega J. Gonadal function abnormalities in sickle cell anemia; studies in male adult patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1976;85(5):601–605. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Modebe O, Ezeh UO. Effect of age on testicular function in adult males with sickle cell anemia. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;63(4):907–912. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dada OA, Nduka EU. Endocrine function and hemoglobinopathies: relation between the sickle cell gene and circulating plasma levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) in adult males. Clinica Chimica Acta. 1980;105(2):269–273. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(80)90469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.El-Hazmi MAF, Bahakim HM, Al-Fawaz I. Endocrine functions in sickle cell anaemia patients. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 1992;38(6):307–313. doi: 10.1093/tropej/38.6.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Abudu EK, Akanmu SA, Soriyan OO, et al. Serum testosterone levels of HbSS (sickle cell disease) male subjects in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Research Notes. 2011;17(4):p. 298. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Osegbe DN, Akinyanju OO. Testicular dysfunction in men with sickle cell disease. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1987;63(736):95–98. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.63.736.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Abdulwaheed OO, Abdulrasaq AA, Sulaiman AK, et al. The hormonal assessment of the infertile male in Ilorin, Nigeria. African Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;3:62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gofrit ON, Rund D, Shapiro A, Pappo O, Landau EH, Pode D. Segmental testicular infarction due to sickle cell disease. Journal of Urology. 1998;160(3, part 1):835–836. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Prasad AS, Schoomaker EB, Ortega J. Zinc deficiency in sickle cell disease. Clinical Chemistry. 1975;21(4):582–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Prasad AS, Cossack ZT. Zinc supplementation and growth in sickle cell disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1984;100(3):367–371. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-3-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Landefeld CS, Schambelan M, Kaplan SL, Embury SH. Clomiphene-responsive hypogonadism in sickle cell anemia. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1983;99(4):480–483. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jiminez CT, Scott RB, Henry WL, et al. Studies in sickle cell anemia. XXVI. The effect of homozygous sickle cell disease on the onset of menarche, pregnancy, fertility, pubescent changes and body growth in Negro subjects. American Journal Of Diseases Of Children. 1966;111:497–503. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Platt OS, Rosenstock W, Espeland MA. Influence of sickle hemoglobinopathies on growth and development. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;311(1):7–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198407053110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zago MA, Kerbauy J, Souza HM, et al. Growth and sexual maturation of Brazilian patients with sickle cell diseases. Tropical and Geographical Medicine. 1992;44(4):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Li M, Fogarty J, Whitney KD, Stone P. Repeated testicular infarction in a patient with sickle cell disease: a possible mechanism for testicular failure. Urology. 2003;62(3):p. 551. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dufau ML. The luteinizing hormone receptor. Annual Review of Physiology. 1998;60:461–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocrine Reviews. 2002;23(2):141–174. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Stocco DM. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annual Review of Physiology. 2001;63:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Tremblay JJ, Hamel F, Viger RS. Protein kinase A-dependent cooperation between GATA and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein transcription factors regulates steroidogenic acute regulatory protein promoter activity. Endocrinology. 2002;143(10):3935–3945. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Epstein LF, Orme-Johnson NR. Acute action of luteinizing hormone on mouse Leydig cells: accumulation of mitochondrial phosphoproteins and stimulation of testosterone synthesis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1991;81(1–3):113–126. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90210-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Epstein LF, Orme-Johnson NR. Regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis: identification of precursors of a phosphoprotein targeted to the mitochondrion in stimulated rat adrenal cortex cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(29):19739–19745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Seebacher T, Beitz E, Kumagami H, Wild K, Ruppersberg JP, Schultz JE. Expression of membrane-bound and cytosolic guanylyl cyclases in the rat inner ear. Hearing Research. 1999;127(1-2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Arakane F, King SR, Du Y, et al. Phosphorylation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) modulates its steroidogenic activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(51):32656–32662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Artemenko IP, Zhao D, Hales DB, Hales KH, Jefcoate CR. Mitochondrial processing of newly synthesized steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), but not total StAR, mediates cholesterol transfer to cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme in adrenal cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(49):46583–46596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Jefcoate C. High-flux mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking, a specialized function of the adrenal cortex. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(7):881–890. doi: 10.1172/JCI16771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Liu J, Rone MB, Papadopoulos V. Protein-protein interactions mediate mitochondrial cholesterol transport and steroid biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(50):38879–38893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Furuta GT, et al. Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;198(5):783–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang Y, Dai Y, Wen J, et al. Detrimental effects of adenosine signaling in sickle cell disease. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(1):79–86. doi: 10.1038/nm.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR. Multiple signaling pathways regulating steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: more complicated than we thought. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19(11):2647–2659. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Receptor-mediated stimulatory effect of atrial natriuretic factor, brain natriuretic peptide, and C- type natriuretic peptide on testosterone production in purified mouse Leydig cells: activation of cholesterol side- chain cleavage enzyme. Endocrinology. 1993;133(5):2141–2149. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Del Punta K, Charreau EH, Pignataro OP. Nitric oxide inhibits leydig cell steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 1996;137(12):5337–5343. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Drewett JG, Adams-Hays RL, Ho BY, Hegge DJ. Nitric oxide potently inhibits the rate-limiting enzymatic step in steroidogenesis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2002;194(1-2):39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Valenti S, Cuttica CM, Fazzuoli L, Giordano G, Giusti M. Biphasic effect of nitric oxide on testosterone and cyclic GMP production by purified rat Leydig cells cultured in vitro. International Journal of Andrology. 1999;22(5):336–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Gambaryan S, Butt E, Marcus K, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type II regulates basal level of aldosterone production by zona glomerulosa cells without increasing expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(32):29640–29648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kass DA, Champion HC, Beavo JA. Phosphodiesterase type 5: expanding roles in cardiovascular regulation. Circulation Research. 2007;101(11):1084–1095. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Andric SA, Kostic TS, Stojilkovic SS. Contribution of multidrug resistance protein MRP5 in control of cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate intracellular signaling in anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147(7):3435–3445. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Fernández-Pérez GC, Tardáguila FM, Velasco M, et al. Radiologic findings of segmental testicular infarction. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2005;184(5):1587–1593. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Madaan S, Joniau S, Klockaerts K, et al. Segmental testicular infarction: conservative management is feasible and safe. European Urology. 2008;53(2):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Han DP, Dmochowski RR, Blasser MH, Auman JR. Segmental infarction of the testicle: atypical presentation of a testicular mass. Journal of Urology. 1994;151(1):159–160. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Urwin GH, Kehoe N, Dundas S, Fox M. Testicular infarction in a patient with sickle cell trait. British Journal of Urology. 1986;58(3):340–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1986.tb09075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Holmes NM, Kane CJ. Testicular infarction associated with sickle cell disease. Journal of Urology. 1998;160(1):p. 130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Bruno D, Wigfall DR, Zimmerman SA, Rosoff PM, Wiener JS. Genitourinary complications of sickle cell disease. Journal of Urology. 2001;166(3):803–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sarma PS. Testis involvement in sickle cell trait. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 1987;35(4):p. 321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Hurt KJ, Musicki B, Palese MA, et al. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase mediates penile erection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(6):4061–4066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052712499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Wood KC, Hsu LL, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease vasculopathy: a state of nitric oxide resistance. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;44(8):1506–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Adams ML, Meyer ER, Sewing BN, Cicero TJ. Effects of nitric oxide-related agents on rat testicular function. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;269(1):230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Hales DB. Testicular macrophage modulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2002;57(1-2):3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(02)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Mondillo C, Pagotto RM, Piotrkowski B, et al. Involvement of nitric oxide synthase in the mechanism of histamine-induced inhibition of leydig cell steroidogenesis via histamine receptor subtypes in sprague-dawley rats. Biology of Reproduction. 2009;80(1):144–152. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Solovey A, Kollander R, Milbauer LC, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide regulate endothelial tissue factor expression in vivo in the sickle transgenic mouse. American Journal of Hematology. 2010;85(1):41–45. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.De Franceschi L, Cappellini MD, Olivieri O. Thrombosis and sickle cell disease. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 2011;37(3):226–236. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gopalakrishna R, Zhen Hai Chen, Gundimeda U. Nitric oxide and nitric oxide-generating agents induce a reversible inactivation of protein kinase C activity and phorbol ester binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(36):27180–27185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]