Abstract

Rickettsiae are obligate intracellular parasitic bacteria that cause febrile exanthematous illnesses such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Mediterranean spotted fever, epidemic, and murine typhus, etc. Although the vector ranges of each Rickettsia species are rather restricted; i.e., ticks belonging to Arachnida and lice and fleas belonging to Insecta usually act as vectors for spotted fever group (SFG) and typhus group (TG) rickettsiae, respectively, it would be interesting to elucidate the mechanisms controlling the vector tropism of rickettsiae. This review discusses the factors determining the vector tropism of rickettsiae. In brief, the vector tropism of rickettsiae species is basically consistent with their tropism toward cultured tick and insect cells. The mechanisms responsible for rickettsiae pathogenicity are also described. Recently, genomic analyses of rickettsiae have revealed that they possess several genes that are homologous to those affecting the pathogenicity of other bacteria. Analyses comparing the genomes of pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains of rickettsiae have detected many factors that are related to rickettsial pathogenicity. It is also known that a reduction in the rickettsial genome has occurred during the course of its evolution. Interestingly, Rickettsia species with small genomes, such as Rickettsia prowazekii, are more pathogenic to humans than those with larger genomes. This review also examines the growth kinetics of pathogenic and non-pathogenic species of SFG rickettsiae (SFGR) in mammalian cells. The growth of non-pathogenic species is restricted in these cells, which is mediated, at least in part, by autophagy. The superinfection of non-pathogenic rickettsiae-infected cells with pathogenic rickettsiae results in an elevated yield of the non-pathogenic rickettsiae and the growth of the pathogenic rickettsiae. Autophagy is restricted in these cells. These results are discussed in this review.

Keywords: Rickettsia, tropism, pathogenicity, spotted fever group, typhus group, vector, tick, insect

Introduction

Rickettsioses in the broad sense are caused by a variety of gram-negative bacteria from the Rickettsia, Orientia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, or Neorickettsia genera. Rickettsia are now further classified into the typhus group (TG) and spotted fever group (SFG; Table 1), although Orientia used to belong to the scrub TG of Rickettsia (Tamura et al., 1995; Fournier et al., 2005). Coxiella, the causative agent of Q fever, used to be classified into the Rickettsiales order but now belongs to the Legionellales order (Weisburg et al., 1989). As Rickettsia are obligate intracellular parasites, many of the mechanisms involved in their attachment and internalization into host cells are shared by viruses.

Table 1.

Classifications, vectors, and reservoirs of Rickettsia that are known to be pathogenic to humans.

| Antigenic group | Species | Disease | Vector | Reservoir(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spotted fever group | R. aeschlimannii | Rickettsiosis | Tick | Unknown |

| R. africae | African tick-bite fever | Tick | Ruminants | |

| R. akari | Rickettsialpox | Mite | Mice, rodents | |

| R. australis | Queensland tick typhus | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. conorii | Mediterranean spotted fever or Boutonneuse fever | Tick | Dogs, rodents | |

| R. felis | Cat flea rickettsiosis | Flea | Cats, rodents, opossums | |

| R. heilongjiangensis | Far Eastern spotted fever | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. helvetica | Aneruptive fever | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. honei | Flinders Island spotted fever, Variant Flinders Island spotted fever, Thai tick typhus | Tick | Rodents, reptiles | |

| R. japonica | Japanese spotted fever or Oriental spotted fever | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. massiliae | Mediterranean spotted fever-like disease | Tick | Unknown | |

| R. parkeri | Maculatum infection | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. rickettsii | Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Febre maculosa, São Paulo exanthematic typhus, Minas Gerais exanthematic typhus, Brazilian spotted fever | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. sibirica | North Asian tick typhus, Siberian tick typhus | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. sibirica mongolotimonae | Lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis | Tick | Rodents | |

| R. slovaca | Tick-borne lymphadenopathy (TIBOLA), Dermacentor-borne necrosis and lymphadenopathy (DEBONEL) | Tick | Lagomorphs, rodents | |

| Typhus group | R. prowazekii | Epidemic typhus, Brill-Zinsser disease | Louse | Humans, flying squirrels |

| R. typhi | Murine typhus | Flea | Rodents |

Rickettsiae cause febrile exanthematous illnesses, such as spotted fever, epidemic, and murine typhus, etc. (Dyer et al., 1931; Zinsser and Castaneda, 1933). Until nearly two decades ago, only five species of SFG rickettsiae (SFGR), R. rickettsii, R. conorii, R. sibilica, R. australis, and R. akari, which are responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Wolbach, 1919), Mediterranean spotted fever or Boutonneuse fever (Brumpt, 1932), North Asian tick typhus or Siberian tick typhus (Shmatikov and Velik, 1939), Queensland tick typhus (Plotz et al., 1946), and Rickettsialpox (Huebner et al., 1946), respectively, were known to be pathogenic. However, since the isolation and identification of a new SFGR species, R. japonica, from Japanese patients with a form of SFG rickettsiosis known as Japanese spotted fever or Oriental spotted fever (Uchida et al., 1988, 1989, 1991, 1992; Uchiyama and Uchida, 1988; Uchiyama et al., 1991), many pathogenic SFGR species have been newly isolated and identified, and some of the previously identified SFGR species have now been recognized as pathogenic (Table 1; Beati and Raoult, 1993; Beati et al., 1993, 1997; Kelly et al., 1996; Raoult et al., 1997; Stenos et al., 1998; Fournier et al., 2003, 2005; Mediannikov et al., 2004; Paddock et al., 2004). More recently, R. bellii was isolated from amebas, and it was suggested that it should be classified into the ancestral group (AG), which contains Rickettsia species that have been demonstrated by phylogenetic analyses to have the oldest genomic features among the previously isolated and identified Rickettsia species (Philip et al., 1983; Stohard et al., 1994; Gillespie et al., 2012). R. bellii displays weaker pathogenicity in experimental animals than R. conorii, although its pathogenicity in humans remains unknown (Ogata et al., 2006). Although the mechanism by which rickettsiae cause disease has not been well established, it is thought that rickettsial pathogenicity involves the infiltration of cells into the vascular environment, hemorrhaging, and thrombosis due to the degeneration of endothelial vein cells caused by the growth of the rickettsiae. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) on the outer membranes of rickettsiae are also thought to participate in the eruption, pyrexia, and endotoxin shock observed during the course of rickettsial infection.

It is worth noting that the vector ranges of each rickettsial species are rather restricted; i.e., the vectors for SFGR species are usually ticks (except those for R. akari and R. felis, which are mites and fleas, respectively) belonging to Arachnida. On the other hand, those for TGR species are lice and fleas, which belong to Insecta (Table 1; Higgins et al., 1996). R. felis carries its pRF genes on a plasmid so it does not fully meet the criteria for the SFG or TG. Rather, this indicates that R. felis has participated in horizontal gene transfer involving the AG and might be better classified into a transitional group along with R. akari, which displays both SFG and TG characteristics (Gillespie et al., 2007, 2012). This plasmid might have been incorporated into the chromosomes of the other Rickettsia during the course of their evolution (Gillespie et al., 2007). The mechanisms responsible for the vector tropism of rickettsiae have not been studied in detail.

Tropism of Rickettsiae toward Arthropod Vectors and Cultured Cells

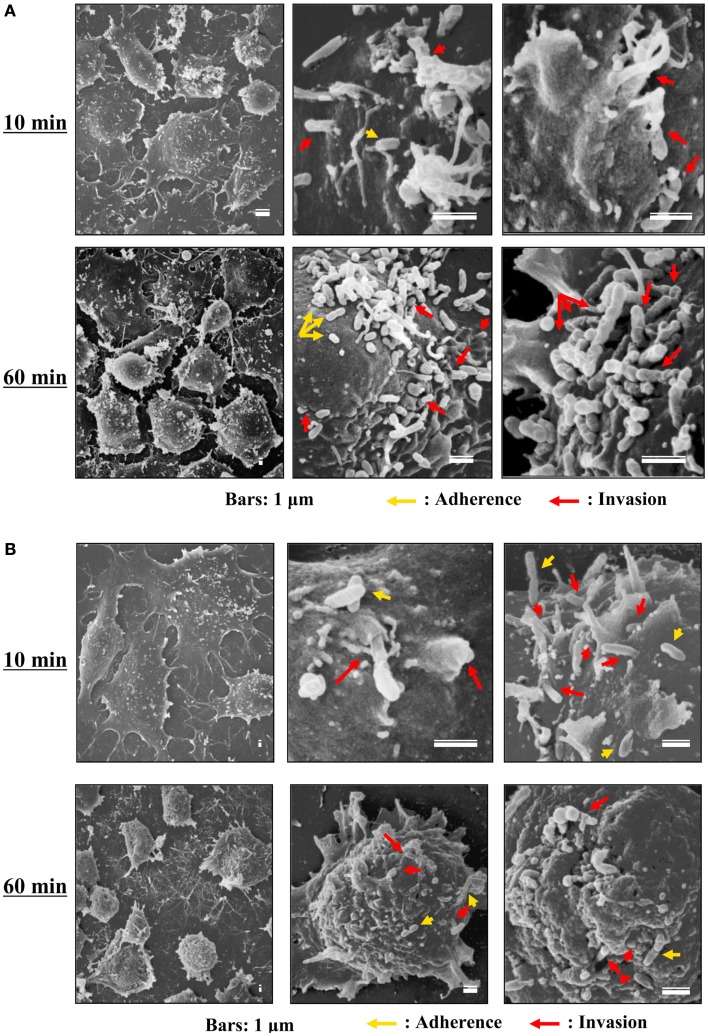

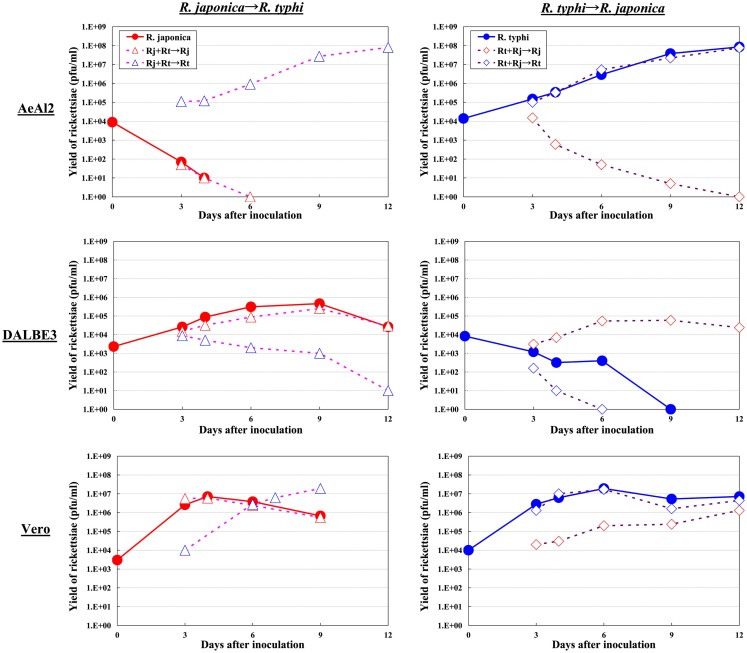

Although the relationships between rickettsiae and their vectors are relatively fixed, the mechanisms responsible for the tropism of rickettsiae toward arthropod vectors have not been elucidated. Studies using cell lines derived from arthropods are indispensable for clarifying these mechanisms. In studies using insect cells, Uchiyama reported that the growth of some SFGR species, R. japonica, and R. montanensis, was restricted in the NIAS-AeAl-2 (AeAl2) insect cell line, which is derived from Aedes albopictus, even though SFGR species have been demonstrated to be capable of adhering to and invading these cells (Figures 1–3; Mitsuhashi, 1981; Mizuki et al., 1999; Noda et al., 2002; Uchiyama, 2005). Scanning and transmission electron microscopy confirmed these results (Figure 3; Uchiyama, 2006). Rickettsiae seem to begin their invasion of AeAl2 cells immediately after adhering to them. The superinfection of SFGR-infected AeAl2 cells with a TGR species on day three of infection resulted in the growth of the TGR species but not the SFGR species. Furthermore, the SFGR-infected AeAl2 cells suffered rapid cell death; however, as no DNA fragmentation, lobed nuclei, or peripheral chromosome condensation were observed, the growth inhibition of these cells was possibly due to their non-apoptotic necrotic cell death. Concerning this issue, induced cell death (subsequently renamed programmed necrosis), which is one of the candidates for the mechanism responsible for growth inhibition, has been found to act in opposition to anti-apoptotic factors (Laster et al., 1988; Holler et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2009; He et al., 2009). For example, cells infected with Cowpox virus cause tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced programmed necrosis, which is opposed by the anti-apoptosis factor CrmA (Chan et al., 2003). When T cells or fibroblastic cells are infected with the Vaccinia virus, apoptosis is inhibited by the anti-apoptotic factor B13R/Spi2; however, TNF-induced programmed necrosis can also occur (Cho et al., 2009). Thus, programmed necrosis might occur when AeAl2 cells are infected with SFGR. Contrary to our results, a previous report found that some non-pathogenic SFGR species, R. montanensis, and R. peacockii, were able to grow in two mosquito cell lines (the A. albopictus cell line Aa23 and the Anopheles gambiae cell line Sua5B; Sakamoto and Azad, 2007). The reason for this discrepancy is poorly understood; however, the abovementioned growth was only detected by FISH and PCR, rather than in an infective assay. Another report found that the transcription of spoT gene paralogs was suppressed during the maintenance of R. conorii in A. albopictus (C6/36) cells at 10°C for 38 days. Shifting the temperature to 37°C resulted in a rapid upregulation of spoT1 gene expression (Rovery et al., 2005). Although R. conorii were confirmed to be able to survive in the cells at low temperature, their growth was not directly assayed after the temperature was increased.

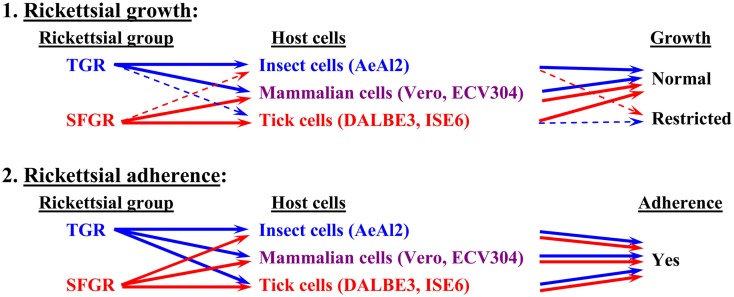

Figure 1.

Basic tropism of rickettsiae toward cultured cells. The growth of SFGR and TGR was monitored in cells derived from ticks, insects, and mammals. SFGR grew well in tick cells, while TGR grew well in insect cells. However, the growth of SFGR was restricted in insect cells and that of TGR was restricted in tick cells. Both groups of pathogenic rickettsiae grew well in mammalian cells. Both groups of rickettsiae were confirmed to be capable of adhering to all of the tested cells.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy of cells infected with TGR and SFGR. (A) AeAl2 cells infected with R. typhi at 10 and 60 min after infection. (B) AeAl2 cells infected with R. japonica at 10 and 60 min after infection. Successful adherence to and invasion of AeAl2 insect cells was achieved by both TGR and SFGR soon after their inoculation. The yellow and red arrows indicate adherent and invading rickettsiae, respectively.

As for studies using tick cell lines, several reports have demonstrated the growth of SFGR species in cells derived from ticks (Policastro et al., 1997; Munderloh et al., 1998). In our study (Uchiyama et al., 2009), the DALBE3 cell line from Dermacentor albipictus and the ISE6 cell line from Ixodes scapularis were inoculated with R. japonica and R. conorii as SFGR species and R. prowazekii and R. typhi as TGR species. The SFGR grew well in these tick cells as well as in Vero, HeLa, and ECV304 mammalian cells (Figures 1 and 2). On the contrary, the growth of TGR was restricted in these tick cells, even though they successfully adhered to the cells, which was also true for other combinations of rickettsiae and host cells. These findings were confirmed by transmission electron microscopy. Rickettsiae were also found to be able to escape into the cytoplasm from phagosomes after being engulfed by the tick cells. Thus, the observed growth restriction occurred after these steps, although the precise mechanism responsible for it is yet to be elucidated. These results from studies using various combinations of SFGR or TGR and tick or insect cells suggest that the host vector tropism of rickettsiae is at least partially based on host cellular tropism (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Growth kinetics of SFGR and TGR in insect, tick, and mammalian cells. Various cultured cells were infected with SFGR alone or TGR alone, and the yield of rickettsiae was monitored. Some of the infected cultures were superinfected with TG or SFGR, respectively, on day three of infection, and the growth of each Rickettsia species was monitored.

Pathogenicity of Rickettsiae

As shown in Table 1, many rickettsial species have displayed evidence of being pathogenic to humans. On the other hand, many other species have not displayed any evidence of being pathogenic to humans, some of which might be weakly pathogenic. To date, various putative factors that might be associated with the pathogenicity of rickettsiae have been proposed; however, the molecular basis for the pathogenicity of rickettsiae is yet to be precisely established.

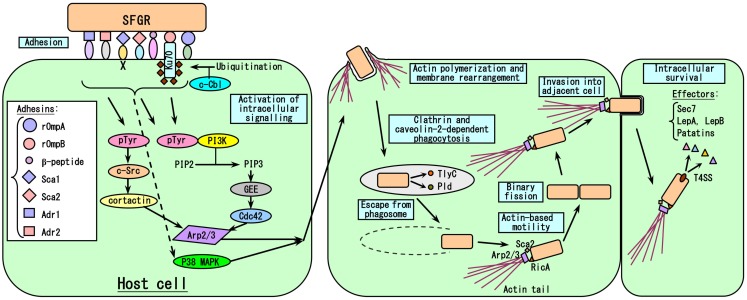

It is reasonable to think that the degree of growth of Rickettsia in human blood vessels; i.e., endothelial cells (EC), primarily determines the severity of their effects on the host, with the exception of R. akari, the causative agent of Rickettsialpox, which principally targets macrophages (Walker et al., 2007). Thus, every step of the growth of rickettsiae in host cells could affect their pathogenicity. The events involved in host cell infection by rickettsiae are summarized in Figure 4. The first steps involve the adherence of the rickettsiae to host cells and their subsequent invasion of these cells, since Rickettsia are obligate intracellular parasitic bacteria. Internalization occurs within minutes, and rickettsiae escape from phagosomes into the cytoplasm via the phospholipase activities of hemolysin C (TlyC) and phospholipase D (Pld; Teysseire et al., 1995; Whitworth et al., 2005). It has been clarified that among the 17 subfamilies of Sca autotransporter proteins, rOmpA (=Sca0), and rOmpB (=Sca5) are involved in host cell adherence and invasion by rickettsiae. rOmpA is one of the major surface antigen proteins of SFGR, and treatment with the antibody against rOmpA or immunization with recombinant rOmpA protected animal models against infection by rickettsiae (Anacker et al., 1985, 1987; McDonald et al., 1987; McDonald et al., 1988; Vishwanath et al., 1990; Sumner et al., 1995; Li et al., 1988; Crocquet-Valdes et al., 2001). The role of rOmpA in the adherence of rickettsiae to host cells has also been examined using cultured cells (Li and Walker, 1998). However, TG rickettsiae do not possess rOmpA, although a remnant (369 bp) of its ORF (6,063 bp) still exists in the equivalent region in R. prowazekii. rOmpB, which is the only major surface antigen protein common to the genus Rickettsia, was also confirmed to play roles in host cell adherence and invasion by rickettsiae in studies using Escherichia coli expressing recombinant R. japonica rOmpB on their surface (Uchiyama, 1999; Uchiyama et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2009). rOmpB is well conserved among the Rickettsia genus including SFGR and TGR, e.g., the rOmpB amino acid sequences of R. prowazekii and R. conorii share 70% homology, which might reflect the importance of the molecule for rickettsial growth (Carl et al., 1990; Gilmore et al., 1991; Hahn et al., 1993). rOmpB might also play other roles, e.g., in the maintenance of the structure of the bacteria or as a molecular sieve, etc. rOmpB associates with Ku70 on the plasma membrane (Martinez et al., 2005), and this interaction is sufficient to mediate the rickettsial invasion of non-phagocytic host cells (Chan et al., 2009). Clathrin and caveolin-2-dependent endocytosis are responsible for the internalization of rickettsiae. The recruitment of c-Cbl, a ubiquitin ligase, to the entry site is also required for the ubiquitination of Ku70 (Martinez et al., 2005). R. conorii enters non-phagocytic cells via an Arp2/3 complex-dependent pathway (Martinez and Cossart, 2004). Pathways involving Cdc42, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, c-Src, cortactin, and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins activate Arp2/3, resulting in localized actin rearrangement during rickettsial entry. Furthermore, activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase module facilitates host cell invasion by R. rickettsii in vitro (Rydkina et al., 2005, 2008). Recently, it has been clarified that some of the other outer membrane proteins belonging to the Sca family, Sca1, and Sca2, also play roles in host cell adherence and invasion by rickettsiae (Cardwell and Martinez, 2009; Riley et al., 2010). Overlay assays involving biotinylated EC, 2D-PAGE, and mass spectrometry have demonstrated that the β-peptide, Adr1, and Adr2 are also putative rickettsial adhesins (Renesto et al., 2006).

Figure 4.

Model of the rickettsia-host cell interactions that occur during the course of infection. The first step in SFGR entry into host cells is the adhesion of rickettsiae to cells due to the binding of many rickettsial adhesins to host cell receptors, followed by the activation of intracellular signaling pathways that induce actin polymerization and membrane rearrangement, causing the attached rickettsiae to be engulfed. Just after clathrin and caveolin-2-dependent phagocytosis, rickettsiae escape from the phagosomes that engulfed them by secreting the phospholipases TlyC and Pld. In the case of SFGR, the surface molecules RicA and Sca2 recruit Arp2/3 to polymerize actin, resulting in the formation of an actin tail, which aids the movement of the bacteria. However, in the case of TGR, R. prowazekii does not have an actin tail, while R. typhi has a very short actin tail. SFGR invade the adjacent cells very early in the course of the infection. Rickettsiae grow within cells by binary fission. The VirB-related T4SS is essential for the intracellular survival of rickettsiae as it allows them to secrete effector molecules.

In addition to studies of these early events during the course of rickettsial infection, there have been many genomic analyses of the pathogenicity of rickettsiae (Andersson et al., 1998; Li and Walker, 1998; Ogata et al., 2001; Uchiyama, 2003; Joshi et al., 2004; Sahni et al., 2005; Whitworth et al., 2005; Uchiyama et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2009; Fournier et al., 2009; Clark et al., 2011). Rickettsial genomes possess homologs of the virB operon, which is known to be related to the type IV secretion system (T4SS) and might be associated with rickettsial pathogenicity. It was reported that Vero cells that had been infected with R. conorii displayed upregulated virB operon expression when they were exposed to nutrient stress (La et al., 2007). The factors secreted by the T4SS, such as Sec7, LepA, LepB, and patatins, might upregulate the synthesis of nutrients that allow rickettsiae to survive in stressful environments. Moreover, of the ten Staphylococcus aureus genes (capA–M) involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharides, which are related to pathogenicity, three have homologs in the Rickettsia genome (Lin et al., 1994).

The infection of cultured human EC with R. rickettsii induced the early cell-to-cell spread of the bacteria, resulting in widespread membrane damage and finally cell death (Silverman, 1984). However, EC are not only injured by infection, but also initiate cellular responses such as endothelial activation. Specifically, the infection of EC with R. rickettsii or R. conorii induces surface platelet adhesion (Silverman, 1986); the release of von Willebrand factor from Weibel–Palade bodies (Sporn et al., 1991; Teysseire et al., 1992); and increased expression of tissue factor (Teysseire et al., 1992; Sporn et al., 1994), E-selectin (Sporn et al., 1993), IL-1α (Kaplanski et al., 1995; Sporn and Marder, 1996), cell-adhesion molecules (Dignat-George et al., 1997), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Drancourt et al., 1990; Shi et al., 2000). The infection of EC with the TGR R. prowazekii resulted in enhanced prostaglandin secretion (Walker et al., 1990). Thus, EC infected with rickettsiae demonstrate procoagulant and proinflammatory features, which might contribute to the severity of rickettsioses. Rickettsial infection of EC also activates nuclear factor (NF)-κB, which inhibits apoptosis and mediates the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (Joshi et al., 2004; Bechelli et al., 2009). Conversely, EC activated by IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, or RANTES degenerate intracellular rickettsiae through nitric oxide production and hydrogen peroxide production (Valbuena et al., 2002; Rydkina et al., 2004).

A comparative study of rickettsial genomes suggested that the inactivation of some genes by genome reduction during the course of their evolution abrogated host-induced rickettsial growth restriction (Blanc et al., 2007). In fact, a conflicting relationship was detected between a smaller genome size and increased pathogenicity in rickettsiae, e.g., R. prowazekii, which possesses a smaller genome, causes more severe symptoms than Rickettsia species with larger genomes such as R. conorii (Fournier et al., 2009; Botelho-Nevers and Raoult, 2011). A comparison of the growth of the virulent and avirulent strains of R. rickettsii revealed that the relA/spoT gene is essential for growth restriction (Clark et al., 2011).

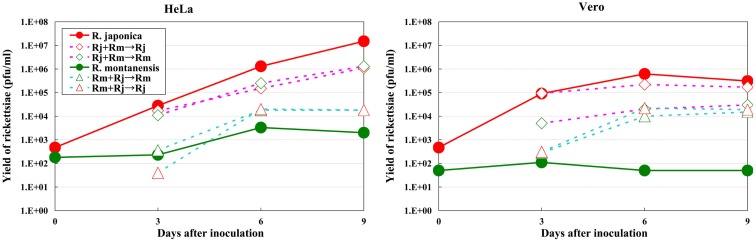

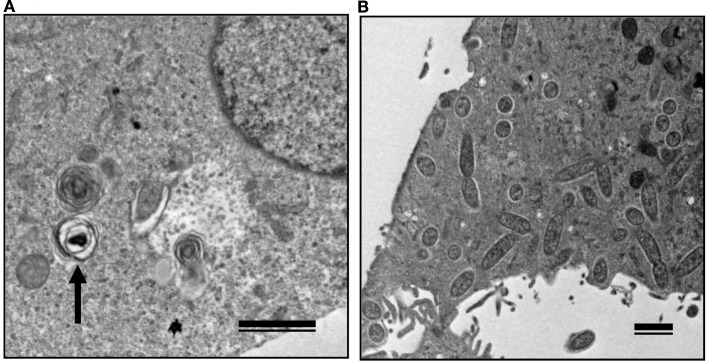

The growth kinetics of pathogenic rickettsiae in mammalian cells were compared with those of non-pathogenic rickettsiae. Vero and HeLa cells derived from mammals were inoculated with a non-pathogenic species of SFGR, R. montanensis (Bell et al., 1963; Uchiyama et al., 2012). The growth of R. montanensis in the mammalian cells was restricted; however, the infection was persistent, and low levels of rickettsiae were produced throughout its course (Figure 5). On the other hand, superinfection of the R. montanensis-infected cells with the pathogenic R. japonica resulted in increased yields of the non-pathogenic R. montanensis and R. japonica growth. Western blotting confirmed that autophagy had been induced in the cells infected with R. montanensis alone. On the contrary, autophagy was restricted in the R. montanensis-infected cells that had been superinfected with pathogenic R. japonica. These results were consistent with the findings of ultrastructural observations (Figure 6). Thus, it is suggested that the growth restriction of the non-pathogenic species, R. montanensis, was at least partly due to the occurrence of autophagy in the infected cells and that the pathogenic species, R. japonica, might secrete an unidentified autophagy restriction factor(s). Although autophagy is one of the innate defense systems against invading microbes, other pathogenic bacteria that display intracellular growth, such as Shigella, Listeria, and Burkholderia, also possess mechanisms for escaping from autophagic degeneration (Sasakawa, 2010). Shigella escapes from autophagic recognition by secreting IcsB via the type III secretion system (TTSS; Ogawa et al., 2005). Listeria recruits the Arp2/3 complex and Ena/VASP to its surface via the bacterial ActA protein and disguises them from autophagic recognition (Yoshikawa et al., 2009), and Burkholderia secretes the BopA protein via the TTSS to evade autophagy (Cullinane et al., 2008). It is also known that the BopA protein shares 23% homology with IcsB of Shigella. Another of the putatively non-pathogenic SFGR, Rickettsia sp. LON, which was isolated from Haemaphysalis longicornis (a tick), but has never been isolated from human spotted fever patients in Japan (Fujita, 2008; Hanaoka et al., 2009), is genetically closely related to R. japonica and in fact is classified within the R. japonica group. Its growth in mammalian cells was examined in a recent study (Uchiyama and Fujita, 2012). The growth of Rickettsia sp. LON is restricted in mammalian cells, as was found for R. montanensis. However, its growth can be recovered by superinfection of the pathogenic R. japonica. These results further strengthen the hypothesis that the degree of rickettsial growth in mammalian cells basically determines the pathogenicity of Rickettsia. Another non-pathogenic Rickettsia, R. peacockii, which is also known as the East Side agent, was isolated from Rocky Mountain Wood ticks (Dermacentor andersoni) from Montana, USA (Bell et al., 1963; Burgdorfer et al., 1981). R. rickettsii-carrying D. andersoni display a markedly reduced prevalence on the east side of the Bitterroot Valley, while Rocky Mountain spotted fever predominantly occurs on the west side of the valley (Philip and Casper, 1981). Thus, the presence of R. peacockii in D. andersoni ticks might prevent the transovarial transmission of R. rickettsii and limit its spread in the tick population, although it is uncertain whether R. peacockii actively interferes with R. rickettsii in ticks or whether ticks carrying R. peacockii have a reproductive advantage over those carrying R. rickettsii. R. rickettsii has been demonstrated to have a lethal effect on its tick vector D. andersoni (Niebylski et al., 1999). A comparative study has also been performed of the genome sequences of the pathogenic R. rickettsii and the non-pathogenic R. peacockii (Niebylski et al., 1997; Felsheim et al., 2009). In R. peacockii, the genes encoding an ankyrin repeat containing protein, DsbA, RickA, protease II, rOmpA, Sca1, and a putative phosphoethanolamine transferase, which are related to its pathogenicity, were deleted or mutated. The gene coding for the ankyrin repeat containing protein is especially noteworthy as it is also mutated in the attenuated Iowa strain of R. rickettsii. The precise mechanisms by which these factors contribute to the pathogenicity of SFGR are yet to be clarified.

Figure 5.

Growth kinetics of non-pathogenic and pathogenic SFGR in mammalian cells. The growth of non-pathogenic and pathogenic rickettsiae was monitored. Some of the cells that had been infected with non-pathogenic R. montanensis were superinfected with pathogenic R. japonica on day three of infection, and the growth of each Rickettsia was monitored. The growth of non-pathogenic SFGR was restricted in mammalian cells. The superinfection of the infected cells with pathogenic SFGR induced an elevated yield of the non-pathogenic SFGR and the growth of the pathogenic species.

Figure 6.

Transmission electron microscopy of Vero cells infected with non-pathogenic and pathogenic SFGR. (A) Vero cells infected with R. montanensis alone was observed at 7 days after infection. An arrow marks a degenerating rickettsia in an autophagosome-like vacuole. (B) R. montanensis-infected cells were superinfected with R. japonica on day three of infection and observed at 7 days after the first infection. Many free rickettsiae around 1 μm in length surrounded by halos and those in the course of binary fission were seen in the cytoplasm. Bars, 1 μm.

Perspectives

The vector tropism of rickettsiae seems to correspond with their growth in cultured mammalian cells. It has been clarified that the growth restriction of SFGR in AeAl2 cells depends on the non-apoptotic cell death induced after host cell adherence and invasion by rickettsiae. It is important to analyze the mechanisms responsible for this cell death and the cell death inhibition observed in AeAl2 cells infected with TGR. Moreover, the mechanisms responsible for the restriction of TGR growth in tick cells and the abrogation of the growth restriction in tick cells infected with SFGR also need to be elucidated.

A relationship was detected between the ability of Rickettsia species to grow in cultured mammalian cells and their pathogenicity; however, the growth abilities of Rickettsia species are affected by many host and rickettsial factors during the various stages of rickettsial infection. In order to elucidate the mechanisms governing rickettsiae pathogenicity, it is necessary to compare these factors between pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains.

Although I have attempted to elucidate the relationships between various rickettsiae species and cell types in this review, it is also necessary to clarify the roles of innate and acquired immunity against rickettsiae infection.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C; 21590481) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and by a Grant-in-Aid for Research on Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases (H21-Shinkou-Ippan-006) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

References

- Anacker R. L., List R. H., Mann R. E., Hayes S. F., Thomas L. A. (1985). Characterization of monoclonal antibodies protecting mice against Rickettsia rickettsii. J. Infect. Dis. 151, 1052–1060 10.1093/infdis/151.6.1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker R. L., Mcdonald G. A., List R. H., Mann R. E. (1987). Neutralizing activity of monoclonal antibodies to heat-sensitive and heat-resistant epitopes of Rickettsia rickettsii surface proteins. Infect. Immun. 55, 825–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson S. G. E., Zomorodipour A., Andersson J. O., Sicheritz-Pontén T., Alsmark U. C. M., Podowski R. M., Näslund A. K., Eriksson S.-S., Winkler H. H., Kurland C. G. (1998). The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396, 133–140 10.1038/24094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beati L., Meskini M., Thiers B., Raoult D. (1997). Rickettsia aeschlimannii sp. nov., a new spotted fever group Rickettsia associated with Hyalomma marginatum ticks. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47, 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beati L., Peter O., Burgdorfer W., Aeschlima A., Raoult D. (1993). Confirmation that Rickettsia helvetica sp. nov. is a distinct species of the spotted fever group of Rickettsiae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43, 521–526 10.1099/00207713-43-4-839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beati L., Raoult D. (1993). Rickettsia massiliae sp. nov., a new spotted fever group Rickettsia. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43, 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechelli J. B., Rydkina E., Colonne P. M., Sahni S. K. (2009). Rickettsia rickettsii infection protects human microvascular endothelial cells against staurosporine-induced apoptosis by a cIAP2-independent mechanism. J. Infect. Dis. 119, 1389–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. J., Kohls G. M., Stenner H. G., Lackman D. B. (1963). Nonpathogenic rickettsias related to the spotted fever group isolated from ticks, Dermacentor variabilis and Derrnacentor andersoni from Eastern Montana. J. Immunol. 90, 770–781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G., Ogata H., Robert C., Audic S., Suhre K., Vestris G., Claverie J.-M., Raoult D. (2007). Reductive genome evolution from the mother of Rickettsia. PLoS Genet. 3, e14 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botelho-Nevers E., Raoult D. (2011). Host, pathogen and treatment -related prognostic factors in rickettsiosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30, 1139–1150 10.1007/s10096-011-1208-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumpt E. (1932). Longevité du virus de la fièvre boutonneuse (Rickettsia conorii, n. sp.) chez la tique Rhipicephalus sanguineus. C. R. Seances Soc. Biol. Fil. 110, 1119–1202 [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorfer W., Hayes S. F., Mavros A. J. (1981). “Nonpathogenic rickettsiae in Dermacentor andersoni: a limiting factor for the distribution of Rickettsia rickettsii,” in Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases, eds Burgdorfer W., Anacker R. L. (New York, NY: Academic Press; ), 585–594 [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell M. M., Martinez J. J. (2009). The Sca2 autotransporter protein from Rickettsia conorii is sufficient to mediate adherence to and invasion of cultured mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 77, 5272–5280 10.1128/IAI.00201-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl M., Dobson M. E., Ching W.-M., Dasch G. A. (1990). Characterization of the gene encoding the protective paracrystalline-surface layer protein of Rickettsia prowazekii: presence of a truncated identical homolog in Rickettsia typhi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 8237–8241 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan F. K.-M., Shisler J., Bixby J. G., Felices M., Zheng L., Appel M., Orenstein J., Moss B., Lenardo M. J. (2003). A role for tumor necrosis factor receptor-2 and receptor-interacting protein in programmed necrosis and antiviral responses. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51613–51621 10.1074/jbc.C300138200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y. G. Y., Cardwell M. M., Hermanas T. M., Uchiyama T., Martinez J. J. (2009). Rickettsial outer-membrane protein B (rOmpB) mediates bacterial invasion through Ku70 in an actin, c-Cbl, clathrin and caveolin 2-dependent manner. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 629–644 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01279.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. S., Challa S., Moquin D., Genga R., Ray T. D., Guildford M., Chan F. K.-M. (2009). Phosphorylation-driven assembly of RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T. R., Ellison D. W., Kleba B., Hackstadt T. (2011). Complementation of Rickettsia rickettsii relA/spoT restores a nonlytic plaque phenotype. Infect. Immun. 79, 1631–1637 10.1128/IAI.00048-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocquet-Valdes P. A., Díaz-Montero C. M., Feng H. M., Li H., Barrett A. D. T., Walker D. H. (2001). Immunization with a portion of rickettsial outer membrane protein A stimulates protective immunity against spotted fever rickettsiosis. Vaccine 20, 979–988 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00377-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinane M., Gong L., Li X., Lazar-Adler N., Tra T., Wolvetang E., Prescott M., Boyce J. D., Devenish R. J., Adler B. (2008). Stimulation of autophagy suppresses the intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in mammalian cell lines. Autophagy 4, 744–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignat-George F., Teysseire N., Mutin M., Bardin N., Lesaule G., Raoult D., Sampol J. (1997). Rickettsia conorii infection enhances vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1-dependent mononuclear cell adherence to endothelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 175, 1142–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drancourt M., Allessi M. C., Levy P. Y., Juhan-Vague I., Raoult D. (1990). Selection of tissue-type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor by Rickettsia conroii and Rickettsia rickettsii-infected cultured endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 58, 2459–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer R. E., Rumreich A., Badger L. F. (1931). Typhus fever: a virus of the typhus type derived from fleas collected from wild rats. Public Health Rep. 46, 334–338 10.2307/4579944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsheim R. F., Kurtti T. J., Munderloh U. G. (2009). Genome sequence of the endosymbiont Rickettsia peacockii and comparison with virulent Rickettsia rickettsii: identification of virulence factors. PLoS ONE 4, e8361 10.1371/journal.pone.0008361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P.-E., Dumler J. S., Greub G., Zhang J., Wu Y., Raoult D. (2003). Gene sequence-based criteria for identification of new Rickettsia isolates and description of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 5456–5465 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5456-5465.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P.-E., El Karkouri K., Leroy1 Q., Robert C., Giumelli B., Renesto P., Socolovschi C., Parola P., Audic S., Raoult D. (2009). Analysis of the Rickettsia africae genome reveals that virulence acquisition in Rickettsia species may be explained by genome reduction. BMC Genomics 10, 166 10.1186/1471-2164-10-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier P.-E., Gouriet F., Brouqui P., Lucht F., Raoult D. (2005). Lymphangitis-associated rickettsiosis, a new rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia sibirica mongolotimonae: seven new cases and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1435–1444 10.1086/429625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H. (2008). Cell culture system for isolation of disease agents: 15 years of experience in Ohara Research Laboratory. Annu. Rep. Ohara Hosp. 48, 21–42 [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. J., Beier M. S., Rahman M. S., Ammerman N. C., Shallom J. M., Purkayastha A., Bruno S., Sobral S., Azad A. F. (2007). Plasmids and rickettsial evolution: insight from Rickettsia felis. PLoS ONE 2, e226 10.1371/journal.pone.0000266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie J. J., Joardar V., Williams K. P., Driscoll T., Hostetler J. B., Nordberg E., Shukla M., Walenz B., Hill C. A., Nene V. M., Azad A. F., Sobral B. W., Caler E. (2012). A Rickettsia genome overrun by mobile genetic elements provides insight into the acquisition of genes characteristic of an obligate intracellular lifestyle. J. Bacteriol. 194, 376–394 10.1128/JB.06244-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore R. D., Jr., Cieplak W., Jr., Policastro P. F., Hackstadt T. (1991). The 120 kilodalton outer membrane protein (rOmp B) of Rickettsia rickettsii is encoded by an unusually long open reading frame: evidence for protein processing from a large precursor. Mol. Microbiol. 5, 2361–2370 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M.-J., Kim K.-K., Kim I.-S., Chang W.-H. (1993). Cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the crystalline surface layer protein of Rickettsia typhi. Gene 133, 129–133 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90237-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka N., Matsutani M., Kawabata H., Yamamoto S., Fujita H., Sakata A., Azuma Y., Ogawa M., Takano A., Watanabe H., Kishimoto T., Shirai M., Kurane I., Ando S. (2009). Diagnostic assay for Rickettsia japonica. Emerging Infect. Dis. 15, 1994–1997 10.3201/eid1512.090252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Wang L., Miao L., Wang T., Du F., Zhao L., Wang X. (2009). Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-α. Cell 137, 1100–1111 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. A., Radulovic S., Schriefer M. E., Azad A. (1996). Rickettsia felis: a new species of pathogenic Rickettsia isolated from cat fleas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34, 671–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler N., Zaru R., Micheau O., Thome M., Attinger A., Valitutti S., Bodmer J.-L., Schneider P., Seed B., Tschopp J. (2000). Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 1, 489–495 10.1038/82732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner R. J., Jellison W. L., Pomerantiz C. (1946). Rickettsialpox, a newly recognized rickettsial disease; isolation of a Rickettsia apparently identical with the causative agent of rickettsial pox from Allodermanyssus sanguineus, a rodent mite. Public Health Rep. 61, 1677–1682 10.2307/4585913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S. G., Francis C. W., Silverman D. J., Sahni S. K. (2004). NF-κB activation suppresses host cell apoptosis during Rickettsia rickettsii infection via regulatory effects on intracellular localization or levels of apoptogenic and anti-apoptotic proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234, 333–341 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanski G. N., Teysseire N., Farnarier C., Kaplanski S., Lissitzky J. C., Durand J. M., Soubeyrand J., Dinarello C. A., Bongrand P. (1995). IL-6 and IL-8 production from cultured human endothelial cells stimulated by infection with Rickettsia conorii via a cell-associated IL-1α-dependent pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 96, 2839–2844 10.1172/JCI118354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. J., Beati L., Mason P. R., Mathewman L. A., Roux V., Raoult D. (1996). Rickettsia africae sp. nov., the etiological agent of African tick bite fever. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46, 611–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La M.-V., François P., Rovery C., Robineau S., Barbry P., Schrenzel J., Raoult D., Renesto P. (2007). Development of a method for recovering rickettsial RNA from infected cells to analyze gene expression profiling of obligate intracellular bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 71, 292–297 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laster S. M., Wood J. G., Gooding L. R. (1988). Tumor necrosis factor can induce both apoptotic and necrotic forms of cell lysis. J. Immunol. 141, 2629–2634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Lenz B., Walker D. H. (1988). Protective monoclonal antibodies recognize heat-labile epitopes on surface proteins of spotted fever group rickettsiae. Infect. Immun. 56, 2587–2593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Walker D. H. (1998). rOmp A is a critical protein for the adhesion of Rickettsia rickettsii to host cells. Microb. Pathog. 24, 289–298 10.1006/mpat.1997.0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W. S., Cunneen T., Lee C. Y. (1994). Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of genes required for the biosynthesis of type I capsular polysaccharide in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 176, 7005–7016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. J., Cossart P. (2004). Early signaling events involved in the entry of Rickettsia conorii into mammalian cells. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 5097–5106 10.1242/jcs.01382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. J., Seveau S., Veiga E., Matsuyama S., Cossart P. (2005). Ku70, a component of DNA-dependent protein kinase, is a mammalian receptor for Rickettsia conorii. Cell 123, 1013–1023 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald G. A., Anacker R. L., Garjian K. (1987). Cloned gene of Rickettsia rickettsii surface antigen: candidate vaccine for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Science 235, 83–85 10.1126/science.3099387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald G. A., Anacker R. L., Mann R. E., Milch L. J. (1988). Protection of guinea pigs from experimental Rocky Mountain spotted fever with a cloned antigen of Rickettsia rickettsii. J. Infect. Dis. 158, 228–231 10.1093/infdis/158.1.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediannikov O. Y., Sidelnikov Y., Ivanov L., Mokretsova E., Fournier P.-E., Tarasevich I., Raoult D. (2004). Acute tick-borne rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia heilongjiangensis in Russian Far East. Emerging Infect. Dis. 10, 810–817 10.3201/eid1005.030437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi J. (1981). A new continuous cell line from larvae of the mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera, Culicidae). Biomed. Res. 2, 599–606 [Google Scholar]

- Mizuki E., Ohba M., Akao T., Yamashita S., Saitoh H., Park Y. S. (1999). Unique activity associated with noninsecticidal Bacillus thuringiensis parasporal inclusions: in vitro cell-killing action on human cancer cells. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86, 477–486 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munderloh U. G., Hayes S. F., Cummings J., Kurtti T. J. (1998). Microscopy of spotted fever rickettsia movement through tick cells. Microsc. Microanal. 4, 115–121 [Google Scholar]

- Niebylski M. L., Peacock M. G., Schwan T. G. (1999). Lethal effect of Rickettsia rickettsii on its tick vector (Dermacentor andersoni). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebylski M. L., Schrumpf M. E., Burgdorfer W., Fischer E. R., Gage K. L., Schwan T. G. (1997). Rickettsia peacockii sp. nov., a new species infecting wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni, in western Montana. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47, 446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda H., Miyoshi T., Koizumi Y. (2002). In vitro cultivation of Wolbachia in insect and mammalian cell lines. In vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 38, 423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H., Audic S., Renesto-Audiffren P., Fournier P. E., Barbe V., Samson D., Roux V., Cossart P., Weissenbach J., Claverie J. M., Raoult D. (2001). Mechanisms of evolution in Rickettsia conorii and R. prowazekii. Science 293, 2093–2098 10.1126/science.1061471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H., La Scola B., Audic S., Renesto P., Blanc G., Robert C., Fournier P.-E., Claverie J.-M., Raoult D. (2006). Genome sequence of Rickettsia bellii illuminates the role of amoebae in gene exchanges between intracellular pathogens. PLoS Genet. 2, e76 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M., Yoshimori T., Suzuki T., Sagara H., Mizushima N., Sasakawa C. (2005). Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science 307, 727–731 10.1126/science.1106036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock C. D., John W., Sumner J. W., Comer J. A., Zaki S. R., Goldsmith C. S., Goddard J., McLellan S. L., Tamminga C. L., Ohl C. A. (2004). Rickettsia parkeri: a newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 805–811 10.1086/381894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip R. N., Casper E. A. (1981). Serotypes of spotted fever group rickettsiae isolated from Dermacentor andersoni (Stiles) ticks in western Montana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 30, 230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip R. N., Casper E. A., Anacker R. L., Cory J., Hayes S. F., Burgdorfer W., Yunker E. (1983). Rickettsia bellii sp. nov.: a tick-borne Rickettsia, widely distributed in the United States, that is distinct from the spotted fever and typhus biogroups. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol 33, 94–106 [Google Scholar]

- Plotz H., Smadel J. E., Bennet B. I. (1946). North Queensland tick typhus: studies of the aetiological agent and its relation to other rickettsial diseases. Med. J. Aust. 263–268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro P. F., Munderloh U. G., Fischer E. R., Hackstadt T. (1997). Rickettsia rickettsii growth and temperature-inducible protein expression in embryonic tick cell lines. J. Med. Microbiol. 46, 839–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoult D., Berbis P., Roux V., Xu W., Maurin M. (1997). A new tick-transmitted disease due to Rickettsia slovaca. Lancet 350, 112–113 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61813-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renesto P., Samson L., Ogata H., Azza S., Fourquet P., Gorvel J.-P., Heinzen R. A., Raoult D. (2006). Identification of two putative rickettsial adhesins by proteomic analysis. Res. Microbiol. 158, 605–612 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley S. P., Goh K. C., Hermanas T. M., Cardwell M. M., Chan Y. G. A., Martinez J. J. (2010). The Rickettsia conorii autotransporter protein Sca1 promotes adherence to nonphagocytic mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 78, 1895–1904 10.1128/IAI.01165-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovery C., Renesto P., Crapoulet N., Matsumoto K., Parola P., Ogata H., Raoult D. (2005). Transcriptional response of Rickettsia conorii exposed to temperature variation and stress starvation. Res. Microbiol. 156, 211–218 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydkina E., Sahni S. K., Santucci L. A., Turpin L. C., Baggs R. B., Silverman D. J. (2004). Selective modulation of antioxidant enzyme activities in host tissues during Rickettsia conorii infection. Microb. Pathog. 36, 293–301 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydkina E., Silverman D. J., Sahni S. K. (2005). Activation of p38 stress-activated protein kinase during Rickettsia rickettsii infection of human endothelial cells: role in the induction of chemokine response. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 1519–1530 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydkina E., Turpin L. C., Sahni S. K. (2008). Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase module facilitates in vitro host cell invasion by Rickettsia rickettsii. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 1172–1175 10.1099/jmm.0.47806-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni S. K., Rydkina E., Sahni A., Joshi S. G., Silverman D. J. (2005). Potential roles for regulatory oxygenases in rickettsial pathogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1063, 207–214 10.1196/annals.1355.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto J. M., Azad A. F. (2007). Propagation of arthropod-borne Rickettsia spp. in two mosquito cell lines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 6637–6643 10.1128/AEM.02101-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakawa C. (2010). A new paradigm of bacteria-gut interplay brought through the study of Shigella. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 86, 229–243 10.2183/pjab.86.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi R. J., Simpson-Haidaris P. J., Marder V. J., Silverman D. J., Sporn L. A. (2000). Post-transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression during Rickettsia rickettsii infection. Microb. Pathog. 28, 127–133 10.1006/mpat.1999.0333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmatikov M. D., Velik M. A. (1939). Tick-borne spotted fever. Klin. Med. (Mosk.) 7, 124–126 [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. J. (1984). Rickettsia rickettsii-induced cellular injury of human vascular endothelium in vitro. Infect. Immun. 44, 545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. J. (1986). Adherence of platelets to human endothelial cells infected by Rickettsia rickettsii. J. Infect. Dis. 153, 694–700 10.1093/infdis/153.4.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn L. A., Haidaris P. J., Shi R. J., Nemerson Y., Silverman D. J., Marder V. J. (1994). Rickettsia rickettsii infection of cultured human endothelial cells induces tissue factor expression. Blood 83, 1527–1534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn L. A., Lawrence S. O., Silverman D. J., Marder V. J. (1993). E-selectin-dependent neutrophil adhesion to Rickettsia rickettsii-infected endothelial cells. Blood 81, 2406–2412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn L. A., Marder V. J. (1996). Interleukin-1α production during Rickettsia rickettsii infection of cultured endothelial cells: potential role in autocrine cell stimulation. Infect. Immun. 64, 1609–1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn L. A., Shi R. J., Lawrence S. O., Silverman D. J., Marder V. J. (1991). Rickettsia rickettsii infection of cultured endothelial cells induces release of large von Willebrand factor multimers from Weibel–Palade bodies. Blood 78, 2595–2602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenos J., Roux V., Walker D., Raoult D. (1998). Rickettsia honei sp. nov., the aetiological agent of Flinders Island spotted fever in Australia. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48, 1399–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohard D. R., Clark J. B., Fuerst P. A. (1994). Ancestral divergence of Rickettsia bellii from the spotted fever and typhus groups of Rickettsia and antiquity of the genus Rickettsia. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44, 798–804 10.1099/00207713-44-4-798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner J. W., Sims K. G., Jones D. C., Anderson B. E. (1995). Protection of guinea-pigs from experimental Rocky Mountain spotted fever by immunization with baculovirus-expressed Rickettsia rickettsii rOmpA protein. Vaccine 13, 29–35 10.1016/0264-410X(95)80007-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura A., Ohashi N., Urakami H., Miyamura S. (1995). Classification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in a new genus, Orientia gen. nov., as Orientia tsutsugamushi comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45, 589–591 10.1099/00207713-45-2-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teysseire N., Arnoux D., George G., Sampol J., Raoult D. (1992). von Willebrand factor release and thrombomodulin and tissue factor expression in Rickettsia conorii-infected endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60, 4388–4393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teysseire N., Boudier J. A., Raoult D. (1995). Rickettsia conorii entry into Vero cells. Infect. Immun. 63, 366–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Uchiyama T., Koyama A. H. (1988). Isolation of spotted fever group rickettsiae from humans in Japan. J. Infect. Dis. 158, 664–665 10.1093/infdis/158.3.664-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Uchiyama T., Koyama A. H., Yu X. J., Walker D. H., Funato T., Kitamura Y. (1991). “Isolation and identification of Rickettsia japonica, causative agent of spotted fever group rickettsial infections in Japan,” in Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases, eds Kazar J., Raoult D. (Bratislava: Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences; ), 389–395 [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Uchiyama T., Kumano K., Walker D. H. (1992). Rickettsia japonica sp. nov., the etiological agent of spotted fever group rickettsiosis in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42, 303–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Yu X. J., Uchiyama T., Walker D. H. (1989). Identification of a unique spotted fever group Rickettsia from humans in Japan. J. Infect. Dis. 159, 1122–1126 10.1093/infdis/159.6.1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T. (1999). “Role of major surface antigens of Rickettsia japonica in the attachment to host cells,” in Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases at the Turn of the Third Millennium, eds Raoult D., Brouqui P. (Pari: Elsevier; ), 182–188 [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T. (2003). Adherence to and invasion of Vero cells by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing the outer membrane protein rOmpB of Rickettsia japonica. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 990, 585–590 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T. (2005). Growth of typhus group and spotted fever group rickettsiae in insect cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1063, 215–221 10.1196/annals.1355.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T. (2006). “Morphological study on the group-specific inhibition of rickettsial growth in insect cells,” in Proceedings of the 16th International Microscopy Congress. Vol.1. Biological and Medical Science. B-20. Bacteriology and Virology, eds Ichinose H., Sasaki T. (Sapporo: Publication committee of IMC16), 408 [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Fujita H. (2012). Coinfection of mammalian and tick cells with pathogenic and nonpathogenic spotted fever group rickettsiae. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 23, 17461 [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Kawano H., Kusuhara Y. (2006). The major outer membrane protein rOmpB of spotted fever group rickettsiae functions in the rickettsial adherence to and invasion of Vero cells. Microbes Infect. 8, 801–809 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Kishi M., Ogawa M. (2012). Restriction of the growth of a nonpathogenic spotted fever group rickettsia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 64, 42–47 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Ogawa M., Kishi M., Yamashita T., Kishimoto T., Kurane I. (2009). Restriction of the growth of typhus group rickettsiae in tick cells. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15, 332–333 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Uchida T. (1988). Ultrastructural study on Japanese isolates of spotted fever group rickettsiae. Microbiol. Immunol. 32, 1163–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Uchida T., Walker D. H. (1991). “Analysis of antigens of Rickettsia japonica with species-specific monoclonal antibodies,” in Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases, eds Kazar J., Raoult D. (Bratislava: Publishing House of the Slovak Academy of Sciences; ), 396–400 [Google Scholar]

- Valbuena G., Feng H. M., Walker D. H. (2002). Mechanisms of immunity against rickettsiae: new perspectives and opportunities offered by unusual intracellular parasite. Microbes Infect. 4, 625–633 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01581-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath S., Mcdonald G. A., Watkins N. G. (1990). A recombinant Rickettsia conorii vaccine protects guinea pigs from experimental boutonneuse fever and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Infect. Immun. 58, 646–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. H., Hudnall S. D., Szaniawski W. K., Feng H. M. (2007). Monoclonal antibody-based immunohistochemical diagnosis of Rickettsialpox: the macrophage is the principal target. Mod. Pathol. 12, 529–533 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. S., Brown J. S., Hoover C. S., Morgan D. A. (1990). Endothelial prostaglandin secretion: effects of typhus Rickettsiae. J. Infect. Dis. 162, 1136–1144 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburg W. G., Dobson M. E., Samuel J. E., Dasch G. A., Mallavia L. P., Baca O., Mandelco L., Sechrest J. E., Weiss E., Woese C. R. (1989). Phylogenetic diversity of the Rickettsiae. J. Bacteriol. 171, 4202–4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth T., Popov V. L., Yu X. J., Walker D. H., Bouyer D. H. (2005). Expression of the Rickettsia prowazekii pld or tlyC gene in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mediates phagosomal escape. Infect. Immun. 73, 6668–6673 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6668-6673.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolbach S. B. (1919). Studies on Rocky Mountain spotted fever. J. Med. Res. 41, 1–197 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y., Ogawa M., Hain T., Yoshida M., Fukumatsu M., Kim M., Mimuro H., Nakagawa I., Yanagawa T., Ishii T., Kakizuka A., Sztul E., Chakraborty T., Sasakawa C. (2009). Lystera monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognision. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinsser H., Castaneda M. R. (1933). On the isolation from a case of Brill’s disease of a typhus strain resembling the European type. N. Engl. J. Med. 209, 815–819 10.1056/NEJM193310262091701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]