Abstract

The anthrax lethal toxin (LT) enters host cells and enzymatically cleaves MAPKKs or MEKs. How these molecular events lead to death from anthrax remains poorly understood, but published reports suggest a direct effect of LT on vascular permeability. We have found that LT challenge in mice disrupts signaling through Tie-2, a tonically activated receptor tyrosine kinase in the endothelium. Genetic manipulations favoring Tie-2 activation enhanced interendothelial junctional contacts, prevented vascular leakage, and promoted survival following a lethal dose of LT. Cleavage of MEK1/2 was necessary for LT to induce endothelial barrier dysfunction, and activated Tie-2 signaled through the uncleaved fraction of MEKs to prevent LT’s effects on the endothelium. Finally, primates infected with toxin-secreting Bacillus anthracis bacilli developed a rapid and marked imbalance in the endogenous ligands that signal Tie-2, similar to that seen in LT-challenged mice. Our results show that B. anthracis LT blunts signaling through Tie-2, thereby weakening the vascular barrier and contributing to lethality of the disease. Measurement of circulating Tie-2 ligands and manipulation of Tie-2 activity may represent future prognostic and therapeutic avenues for humans exposed to B. anthracis.

Keywords: angiopoietin, edema, infection

Systemic infection with anthrax is uncommon but deadly. Affected individuals develop profound hemoconcentration, edema in and around the lungs, and circulatory collapse. Injection of anthrax lethal toxin (LT) into mice recapitulates cardinal manifestations of systemic anthrax infection, inducing a form of vascular leakage that is devoid of the features of classical bacterial sepsis such as thrombosis and cytokine involvement (1–3).

LT is composed of two secreted proteins, protective antigen (PA) and lethal factor (LF). PA binds transmembrane receptors and noncovalently complexes with LF. After endocytosis, PA forms multimeric pores in the endosome membrane, and these pores translocate LF to the cytoplasm where it enzymatically cleaves MEKs (4–9). Several lines of evidence suggest that LT acts directly on the vasculature: (i) LT enhances the permeability of confluent cultured endothelial cells without causing cell death; (ii) LT attenuates junctional localization of barrier-promoting adhesion proteins; and (iii) LT induces vascular leakage in larval zebrafish without causing cell death (10–12). However, the mechanisms through which LT acts on the vasculature have remained unclear.

The Tie-2 receptor is expressed almost exclusively in the endothelium, with the lung being a rich site of expression (13). Tie-2 is activated by angiopoietin-1 (Angpt-1), a protein secreted by periendothelial cells (i.e., pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells) whose multimerization promotes Tie-2 clustering at cell–cell junctions (14–16). Angpt-1 induces angiogenesis during development (14, 17–19). In mature vessels or confluent endothelial cells, Angpt-1 prevents barrier disruption induced by diverse permeability mediators, including bacterial lipopolysaccharides, vascular endothelial growth factor, mustard oil, and bradykinin (18–21). The antileak effect of Angpt-1 is associated with reduced gap formation between adjacent endothelial cells (20, 21). This reduction in gap formation is achieved by signaling through Tie-2 to vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), a transmembrane protein whose homotypic interaction between adjacent cells is essential for normal barrier function (21–24). A related ligand secreted by activated endothelial cells, angiopoietin-2 (Angpt-2), competitively inhibits Angpt-1 (25). Administration of Angpt-2 to otherwise healthy adult mice induces vascular leakage (24, 26). The effects of anthrax on the angiopoietin–Tie-2 pathway are unknown.

Based upon (i) the prominence of vascular leakage in anthrax across different organisms, (10, 27, 28); (ii) the absence of associated inflammatory cytokine induction; and (iii) the role of the angiopoietin–Tie-2 axis in regulating barrier function, we hypothesized that anthrax lethal toxemia would disturb this barrier-protective pathway and that forced activation of Tie-2 in this setting not only would prevent leakage but also would improve survival. To test this hypothesis, we studied genetic mouse models challenged with LT, human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs), and primates inoculated with toxin-secreting anthrax bacilli.

Results

LT Challenge Reduces Expression of Tie-2 and Its Downstream Barrier Effector Protein VE-Cadherin.

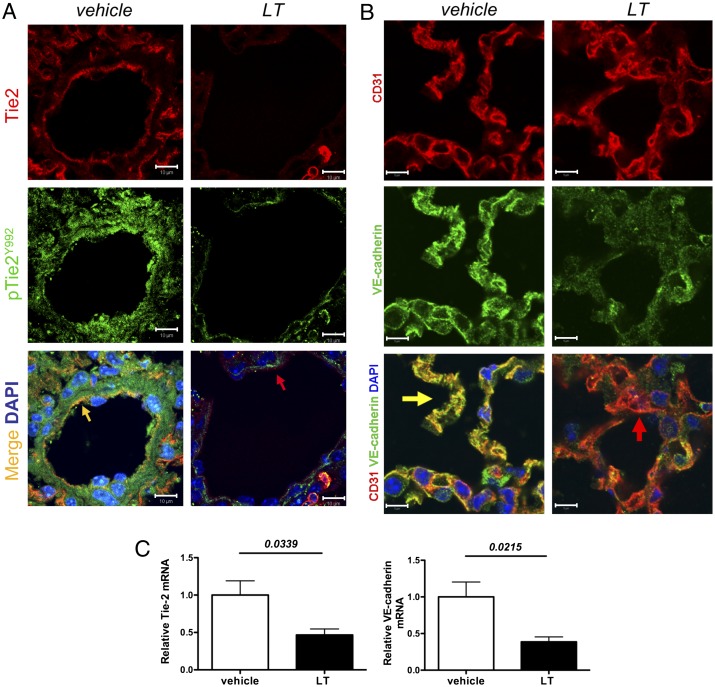

Initial dose-ranging studies of LT confirmed the lethality of 50 μg administered i.v. to adult male C57BL6/J mice and demonstrated that this dose was sufficient to cleave and degrade MEK1/2 (Fig. S1 A and B). Because LT has been reported to induce vascular leakage in the lungs of rodents (29, 30), we used this model to test its effects on Tie-2 and VE-cadherin. Immunohistochemistry revealed decreased Tie-2 and decreased phosphorylated Tie-2 (Fig. 1A). VE-cadherin also was reduced (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1C). We confirmed the reduced expression of Tie-2 and VE-cadherin by semiquantitative real-time PCR on lung homogenates (Fig. 1C). We found no evidence of increased apoptosis to account for this change (Fig. S1D).

Fig. 1.

LT challenge reduces the expression of Tie-2 and its downstream barrier effector protein, VE-cadherin. (A) Fluorescent immunohistochemistry for Tie-2 (red) and pTie-2 (Y992) (green) from murine lungs 72 h after i.v. injection of vehicle or 50 μg LT. Phosphorylation of Tie-2 results in colocalization appearing as yellow in the merged image. Arrows point to endothelium. Images are representative of five animals per group. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (B) Fluorescent immunohistochemistry for VE-cadherin (green) and the endothelial marker CD31 (red) from above conditions. Colocalization appears as yellow in the merged image. Arrows indicate endothelium. Images are representative of five animals per group. (Scale bars: 5 μm.) (C) Real-time PCR of lung homogenates for Tie-2 and VE-cadherin mRNA 72 h after vehicle or LT (n = lungs of six or seven animals per condition).

Tie-2 Activation Confers a Survival Advantage to LT-Challenged Mice and Prevents Disruption of the Vascular Barrier.

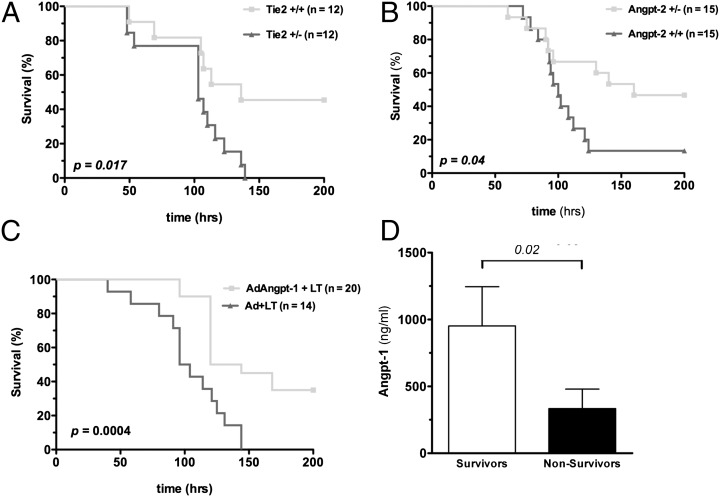

We next tested whether genetic manipulation of Tie-2 and its ligands affected survival after LT injection. Partial deletion of Tie-2 worsened survival, partial deletion of Angpt-2 enhanced survival, and adenoviral Angpt-1 gene transfer improved survival following LT injection (Fig. 2 A–C and Fig. S2). In the gene-transfer experiments, circulating Angpt-1 levels at the time of LT injection were significantly higher in future survivors than in future nonsurvivors (Fig. 2D). Of note, a higher dose of LT was used in the Tie-2 heterozygote survival study because pilot experiments in their CD-1 genetic background showed zero lethality at i.v. LT doses of 25 μg (n = 7 mice) and 50 μg (n = 6 mice).

Fig. 2.

Tie-2 activation confers a survival advantage to LT-challenged mice and prevents disruption of the vascular barrier. (A–C) Survival curves after LT administration to (A) Tie-2 male heterozygous mice vs. littermate controls (100 μg LT per mouse), (B) Angpt-2 heterozygous male mice vs. littermate controls (50 μg LT per mouse), and (C) wild-type mice receiving adenoviral Angpt-1 gene transfer (AdAngpt-1) or control vector (Ad) (50 μg LT per mouse). P values were obtained by log-rank test. (D) Blood was collected via tail vein 48 h after Ad-Angpt-1 administration (i.e., at the time of LT administration), and circulating Angpt-1 expression was measured by ELISA.

Angpt-1 Gene Transfer Enhances Tie-2 Activation During LT Challenge and Is Associated with Reduced Vascular Leakage.

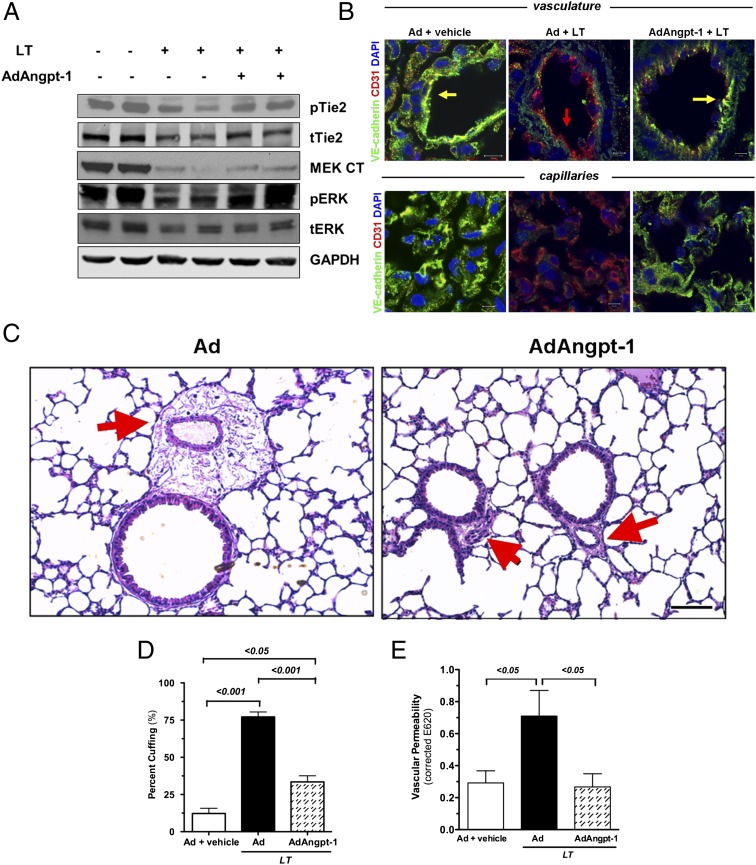

To probe the mechanism of the survival effect associated with Tie-2 activation, we examined the signaling effects downstream of Angpt-1 and LT using a GFP-expressing adenovirus as a control for adenovirus expressing Angpt-1 (Ad-Angpt-1). As expected, LT challenge reduced MEK1/2 levels and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and Angpt-1 gene transfer enhanced Tie-2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3A). As in Fig. 1, LT administration again reduced the expression of VE-cadherin as determined by immunostaining (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3B). Angpt-1 gene transfer was associated with increased expression of Tie-2 and VE-cadherin (Fig. S3C).

Fig. 3.

Angpt-1 gene transfer enhances Tie-2 activation during LT challenge and is associated with reduced vascular leakage. (A) Immunoblots for phosphoTie-2Y992 (pTie2), total Tie-2 (tTie2), MEK1/2 (MEK CT), phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK), and total ERK1/2 (tERK) in lung homogenates obtained 72 h after vehicle or LT treatment. Mice were treated with control adenovirus (−) or Ad-Angpt-1 (+) 48 h before injection of LT or vehicle,. Each lane contains homogenate of a single mouse representative of four mice per group. (B) Fluorescent immunohistochemistry for VE-cadherin (green) and the endothelial marker CD31 (red) 72 h after LT challenge (50 μg i.v.) Colocalization appears as yellow in the merged images. Arrows indicate endothelium. Results shown are representative of five animals per group. (Scale bars: 10 μm for large vessels; 5 μm for capillaries.) (C) Low-power photomicrographs of lung 72 h after i.v. injection of 50 μg LT demonstrating peribronchial cuffing (red arrows) that is not seen with Angpt-1 gene transfer. Representative results of five animals per group are shown. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (D) Ten random transverse sections of both lungs of each animal were scored for the number of bronchi and the fraction exhibiting cuffing. Bar graph depicts the percentage of bronchi positive for cuffing. P < 0.0001 by ANOVA with post hoc pairwise P values as indicated. n = 5 animals per group. (E) Evans blue permeability assay was performed on lungs of mice treated as described above (n = 5–7 animals per group). P < 0.05 by ANOVA with post hoc pairwise P values as indicated.

Previous studies have shown that the multiorgan dysfunction of common bacterial endotoxic shock involves the heart, liver, and kidneys (examples are shown in refs. 31 and 32), but these organs are affected only modestly in murine anthrax lethal toxemia (2, 33). In contrast, the lungs are prominently affected in human systemic anthrax, primate anthrax bacteremia, and rat lethal toxemia; reports in mouse LT models are conflicting (2, 27, 29, 30, 34). To address this issue, we examined the pathology of formalin-insufflated lungs, a technique that prevents tissue distortion by atelectasis. In LT-treated mice, we observed widespread bronchovascular cuffing in the lung, a pathological sign of edema that was significantly less in mice that received Angpt-1 gene transfer before LT (Fig. 3 C and D). We confirmed the vascular leakage associated with LT and the antileakage effect of Angpt-1 with an independent intravascular-dye extravasation method (Fig. 3E). Of note, the combination of Angpt-1 and LT had no major deleterious effects on renal, hepatic, or cardiac structure (Fig. S3D), consistent with previous reports of either agent alone (2, 18, 33).

Role of MEK1/2 in LT-Induced Barrier Dysfunction and Angpt-1–Mediated Barrier Defense Against LT.

In vivo, Angpt-1 gene transfer was associated with enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation despite the MEK1/2-degrading action of LT (Fig. 3A). To study further this phenomenon and the molecular mechanism of Angpt-1’s antileakage effect against LT, we applied LT to HMVECs, a model system in which VE-cadherin expression is reduced, and barrier dysfunction arises without apoptosis (12). First, we compared the effects of LT against a proteolytically inactive missense mutant (ΔLT, E687C in lethal factor). Unlike native LT, ΔLT did not degrade MEK1/2, did not disrupt the cytoskeletal and junctional architecture of confluent HMVECs, and did not enhance the monolayer permeability of confluent HMVECs (Fig. S4 A–C). These results showed that the effects of LT on HMVECs were specific to its enzymatic activity.

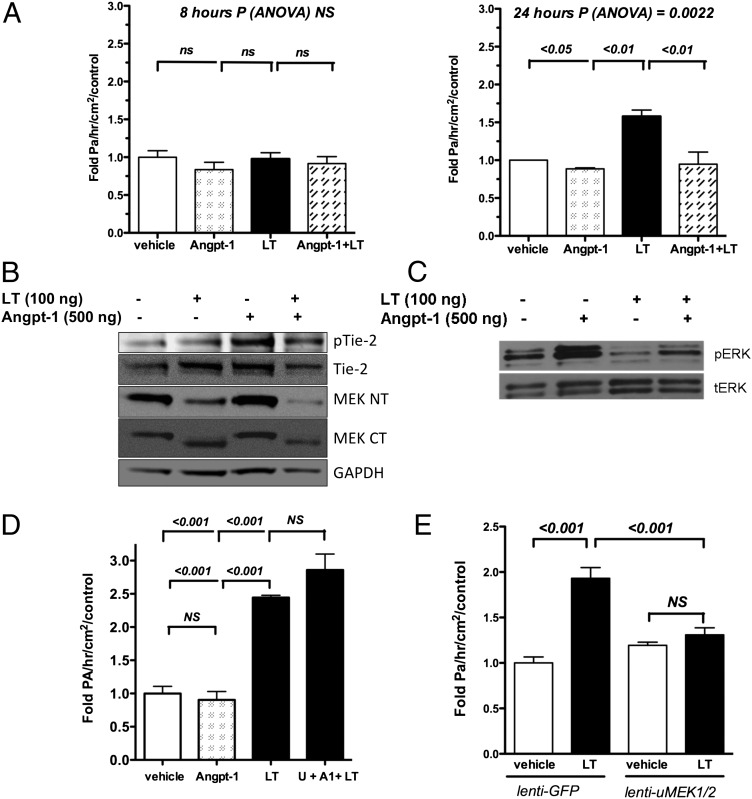

Next, we treated cells with Angpt-1 and LT. The antipermeability effect of Angpt-1 was not seen at 8 h but was observed from 24 through 72 h (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5A). Analogous to the in vivo studies, Angpt-1 signaled an increase of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in LT-treated cells with no discernible effect on MEK1/2 levels (Fig. 4 B and C). Angpt-1 application also prevented the formation of LT-induced actin stress fibers and a paracellular gap (Fig. S5B).

Fig. 4.

The role of MEK1/2 in LT-induced barrier dysfunction and Angpt-1–mediated barrier defense against LT. (A) Transwell permeability assay performed on confluent HMVECs treated with vehicle, Angpt-1 (500 ng/mL), and/or LT (100 ng/mL) for 8 h (Left) or 24 h (Right). n = 3–6 independent experiments per condition, normalized by average response of vehicle-treated cells. P by ANOVA and post hoc pairwise P values as indicated. (B) Representative immunoblots (n = 4 per condition) of HMVEC lysates after 7 h of LT (100 ng/mL) followed by 10 min of Angpt-1 (500 ng/mL) for pTie-2 (Y992), total Tie-2, C-terminal MEK1/2 (MEK CT), and N-terminal MEK1/2 (MEK NT). (C) Representative immunoblots (n = 4 experiments per condition) of HMVEC lysates after 7 h of LT followed by 10 min of Angpt-1 for phosphorylated (pERK) and total ERK1/2 (tERK). (D) Transwell permeability assay performed on HMVECs treated with a control carrier solution, Angpt-1 (500 ng/mL), LT (100 ng/mL), or Angpt-1, LT, and 50 μM U0126 (U + A1 + LT) (n = 3 per condition). P < 0.0001 by ANOVA with post hoc pairwise P values as indicated. (E) Transwell permeability assay performed on HMVECs treated with LT (100 ng/mL) and control lentivirus (lenti-GFP) or equal titer of lentiviruses expressing uncleavable isoforms of MEKs 1 and 2 (lenti-uMEK1/2) normalized for the average response of the vehicle-treated lenti-GFP cells. P < 0.0001 by ANOVA, post hoc pairwise P values as indicated. n = 5 experiments per condition.

We then asked whether Angpt-1 signaled ERK1/2 phosphorylation in LT-treated cells through the remaining fraction of intact MEK1/2. Consistent with this hypothesis, full-length MEK1/2 was detectable even after high doses or long durations of LT, and Angpt-1 still was able to signal ERK1/2 phosphorylation 48 h after LT treatment (Fig. S6 A and B). More importantly, MEK inhibition with U0126 fully abrogated Angpt-1’s abilities to activate ERK1/2 and counteract LT-induced barrier dysfunction (Fig. 4D and Fig. S6 C and D).

To evaluate further the role of MEK1/2 in endothelial barrier defense against LT, we infected HMVECs with lentiviruses encoding functioning mutants of MEK1/2 that cannot be cleaved by LT (uMEK1/2) (Fig. S7A) (34). Junctional staining for VE-cadherin and monolayer barrier function were preserved in uMEK1/2-expressing cells challenged with LT (Fig. 4E and Fig. S7B). Together, these results suggested that LT weakens the endothelial barrier by inactivating MEK1/2 and that Angpt-1 promotes barrier defense against LT by signaling to ERK1/2 through the uncleaved fraction of MEK1/2.

Primates Administered B. anthracis Bacilli Develop Early and Progressive Elevation of Angpt-2.

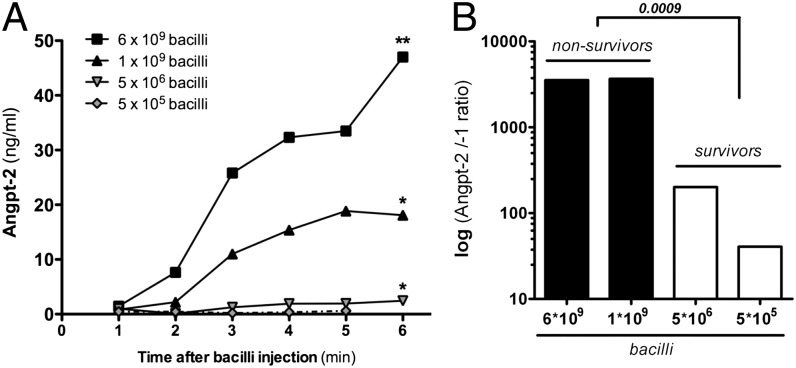

In LT-challenged mice, we observed increased expression and elevated circulating levels of Angpt-2 (Fig. S8). Further, partial deletion of Angpt-2 and gene transfer of Angpt-1 were associated with improved survival in this model (Fig. 2 B and C). To evaluate whether Tie-2 signaling disruptions may be present in another model system of anthrax, we studied baboons inoculated i.v. with varying doses of exotoxin-expressing B. anthracis bacilli (27). Injection of 109 bacilli, a lethal load, was associated with an early and progressive elevation in circulating Angpt-2 (Fig. 5A). Circulating levels of Angpt-1 were lower than circulating levels of Angpt-2 (Fig. S9). The circulating Angpt-2/Angpt-1 ratio 2 h after inoculation was substantially higher in the two baboons that received higher loads of anthrax bacilli and later died (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Primates administered B. anthracis bacilli develop early and progressive elevation of Angpt-2. (A) Four adult baboons were inoculated i.v. at time 0 with different doses of toxigenic 34F2 Sterne strain anthrax bacilli. Venous blood was collected at serial time points for Angpt-2 measurement. P < 0.01 for dose of bacilli and P < 0.01 for time after injection by two-way ANOVA. P values indicate likelihood of the slope being zero by Spearman correlation method. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. (B) Bar graphs (log scale) of the early (120 min) circulating Angpt-2/Angpt-1 ratio separated for different doses administered to each animal.

Discussion

Because the host’s vascular barrier is disrupted before death in animals administered LT, and vascular barrier disruption is a prominent feature of the systemic human disease, we studied the Tie-2 signaling axis, a regulatory pathway upstream of the endothelial barrier effector protein VE-cadherin. Data from LT-challenged mice, HMVECs, and baboons inoculated with live anthrax bacilli all suggest that reduced signaling through Tie-2 may contribute to the breakdown of this barrier in anthrax. Tie-2 activation by Angpt-1 counteracted LT-mediated vascular leakage and reduced its lethality. The data also suggest that intraendothelial MEK1/2 is a critical target for this process. Uncleavable MEK1/2 isoforms prevented LT-induced barrier dysfunction, and inhibition of MEKs abrogated the protective actions of Angpt-1 against LT. This mechanism is supported by a previous study demonstrating that constitutive MEK1/2 activation prevented LT-induced vascular injury in larval zebrafish (35).

We have shown previously that manipulations of the Tie-2 signaling axis lead to reorganization of the endothelial cytoskeleton and junctional apparatus (21, 24, 31). Changes in endothelial cellular structure in turn may affect vessel permeability in vivo (20, 21, 36). Systemic LT has multiple suppressive effects on tonic Tie-2 signaling, including reduction of Tie-2 protein, reduction in the phosphorylation of the remaining Tie-2 protein, and induction of its antagonist, Angpt-2 (a proposed model shown in Fig. S10). We focused the mouse studies on the lung because anthrax has prominent effects on this organ and because Tie-2 is strongly expressed in its vascular bed. Although our data suggest that the major pathophysiological change prevented by Tie-2 activation is pulmonary vascular leakage, it is possible that vascular permeability elsewhere, such as in the cerebral vessels, is important also.

Our genetic studies in mice required the use of different background strains. In the case of Tie-2 heterozygotes on a CD-1 background, we used a higher dose of LT because the dose of 50 μg per mouse was nonlethal. The strain-specific differences in LT LD50 have been characterized extensively (and are summarized in ref. 3), a feature of the model that precluded intergenotype comparisons, such as addressing whether partial deletion of Angpt-2 is a more potent intervention than Angpt-1 gene transfer. However, the goal of the genetic survival studies in Fig. 2 was to ascertain whether several independent manipulations of the Tie-2 signaling axis all consistently implicated an association between greater Tie-2 activation and improved survival. Our exclusive use of littermate controls should permit such a conclusion.

The mechanisms and interrelationships of the changes in the Tie-2 pathway induced by LT merit further investigation. For example, Rho kinase may be a downstream target inhibited by Angpt-1, as we have previously shown for lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial permeability (21). Rho kinase may be similarly involved downstream of LT in the endothelium (37). Angpt-1 ligation of Tie-2 also may signal through the MEK–ERK pathway to exclude the transcription factor Foxo-1 from the nucleus and thereby inhibit Angpt-2 synthesis (38, 39). Future genetic studies may help address whether entry of LT into the host endothelium alone is sufficient to mediate lethality in mice. Because a small fraction of monocytes also expresses Tie-2, and LT is known to induce cytolysis of macrophages from susceptible mice, Tie-2 signaling also may be important in this cell type (40).

The cell-surface receptors for LT, tumor endothelial marker 8, and capillary morphogenesis protein 2 are expressed not only in the endothelium but also more widely throughout mammalian tissues (41, 42). Moreover, the cellular targets of LF, MEKs, also are found in virtually all cells. Given these facts, we find it remarkable that manipulation of a single signaling cascade largely confined to a single cell type, the endothelium, impacts major manifestations of the disease, including its lethality. Because other catastrophic infections also are associated with vascular leakage, disruption of vascular barrier integrity pathways may be a broader adaptation contributing to the virulence of several pathogens (43–45).

Methods

Please see SI Methods for full experimental details.

Mouse Studies.

All experiments were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (46). Eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory), 8- to 9-wk-old Angpt-2 heterozygous (Angpt-2−/−) mice on a 129Sv/BL6 mixed background, and their wild-type littermates (gift of S. Wiegand, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY), and Tie-2 heterozygotes (Tie2 +/−) on a CD-1 background and their wild-type littermates (gift from D. Dumont, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada) were used in this study. Note that survival of inbred mice following LT challenge varies significantly by strain (3). Because of the significant weight variation of CD-1 background mice, we confined those studies to animals weighing 35–45 g. Viral particles (2 × 1010) of Ad-Angpt-1 or control adenovirus (Ad-CMV-GFP) were administered by tail vein 48 h before tail vein injection of LT diluted in sterile PBS to 500 μL. Animals were killed by exsanguination under anesthesia followed by rapid collection of organs into liquid nitrogen for further analysis.

Cell Culture.

Passage 2–6 HMVECs from dermis (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Cell Biology Core Facility; http://cvbr.hms.harvard.edu) or lung (Lonza) were cultured in the endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) FBS and growth factors according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum starvation was performed in EBM-2 medium with 1% (vol/vol) FBS and penicillin-streptomycin. Treatment with LT, U0126, and/or Angpt-1 was preceded by 2 h of serum starvation to observe signaling changes without the confounding effects of growth factors in full medium. To induce apoptosis for a positive control in cleaved caspase-3 measurements, HMVECs were serum starved for 36 h. The dose of LT was adjusted between 100–1,000 ng/mL to achieve equal potency of MEK1/2 cleavage across all experiments.

Baboon Studies.

Papio c. cynocephalus baboons were injected i.v. at time 0 with 34F2 Sterne strain B. anthracis bacteria as described (27). No new animals were used for the current studies, and the measurements presented herein are from venous blood samples obtained from four animals during the prior study. The plasma levels of Angpt-1 and Angpt-2 were measured by commercially available ELISA kit (R & D Systems). The expected coefficient of variation for repeated measurement reported by the manufacturer is <10%. Our average observed coefficient of variation was 8.8% with an SD of 8.7%.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted. Statistical significance was evaluated by a two-sided, unpaired t test unless otherwise noted. For comparisons of more than two groups, we used one-way ANOVA with post hoc pairwise Bonferroni testing. Baboon temporal trend data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (time and dose of bacilli) with corrections for multiple comparisons and were analyzed for trends over time by linear regression using the Spearman method. Survival data were analyzed by log-rank test. Analyses were performed in SPSS and graphs were made using GraphPad Prism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant HL093234 (to S.M.P.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center has filed for patents regarding angiopoietins in anthrax for which S.M.P. is listed as an inventor.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1120755109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cui X, et al. Lethality during continuous anthrax lethal toxin infusion is associated with circulatory shock but not inflammatory cytokine or nitric oxide release in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R699–R709. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00593.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moayeri M, Haines D, Young HA, Leppla SH. Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin induces TNF-alpha-independent hypoxia-mediated toxicity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:670–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI17991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moayeri M, Leppla SH. Cellular and systemic effects of anthrax lethal toxin and edema toxin. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:439–455. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon VM, Leppla SH, Hewlett EL. Inhibitors of receptor-mediated endocytosis block the entry of Bacillus anthracis adenylate cyclase toxin but not that of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1066–1069. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1066-1069.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milne JC, Furlong D, Hanna PC, Wall JS, Collier RJ. Anthrax protective antigen forms oligomers during intoxication of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20607–20612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duesbery NS, et al. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science. 1998;280:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vitale G, Bernardi L, Napolitani G, Mock M, Montecucco C. Susceptibility of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase family members to proteolysis by anthrax lethal factor. Biochem J. 2000;352:739–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klimpel KR, Arora N, Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin lethal factor contains a zinc metalloprotease consensus sequence which is required for lethal toxin activity. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1093–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pannifer AD, et al. Crystal structure of the anthrax lethal factor. Nature. 2001;414:229–233. doi: 10.1038/n35101998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolcome RE, 3rd, et al. Anthrax lethal toxin induces cell death-independent permeability in zebrafish vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2439–2444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712195105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guichard A, et al. Anthrax toxins cooperatively inhibit endocytic recycling by the Rab11/Sec15 exocyst. Nature. 2010;467:854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature09446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warfel JM, Steele AD, D’Agnillo F. Anthrax lethal toxin induces endothelial barrier dysfunction. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1871–1881. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62496-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong AL, et al. Tie2 expression and phosphorylation in angiogenic and quiescent adult tissues. Circ Res. 1997;81:567–574. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suri C, et al. Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell. 1996;87:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KT, et al. Oligomerization and multimerization are critical for angiopoietin-1 to bind and phosphorylate Tie2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20126–20131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis S, et al. Angiopoietins have distinct modular domains essential for receptor binding, dimerization and superclustering. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nsb880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suri C, et al. Increased vascularization in mice overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science. 1998;282:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston G, et al. Angiopoietin-1 protects the adult vasculature against plasma leakage. Nat Med. 2000;6:460–463. doi: 10.1038/74725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurston G, et al. Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science. 1999;286:2511–2514. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baffert F, Le T, Thurston G, McDonald DM. Angiopoietin-1 decreases plasma leakage by reducing number and size of endothelial gaps in venules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H107–H118. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00542.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mammoto T, et al. Angiopoietin-1 requires p190 RhoGAP to protect against vascular leakage in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23910–23918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corada M, et al. Vascular endothelial-cadherin is an important determinant of microvascular integrity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9815–9820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavard J, Patel V, Gutkind JS. Angiopoietin-1 prevents VEGF-induced endothelial permeability by sequestering Src through mDia. Dev Cell. 2008;14:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parikh SM, et al. Excess circulating angiopoietin-2 may contribute to pulmonary vascular leak in sepsis in humans. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maisonpierre PC, et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roviezzo F, et al. Angiopoietin-2 causes inflammation in vivo by promoting vascular leakage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:738–744. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.086553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Lupu F, Taylor FB, Jr, Kinasewitz G, Kurosawa S. Sepsis and pathophysiology of anthrax in a nonhuman primate model. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:433–444. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gozes Y, Moayeri M, Wiggins JF, Leppla SH. Anthrax lethal toxin induces ketotifen-sensitive intradermal vascular leakage in certain inbred mice. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1266–1272. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1266-1272.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo SR, et al. Anthrax toxin-induced shock in rats is associated with pulmonary edema and hemorrhage. Microb Pathog. 2008;44:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolando M, et al. Injection of Staphylococcus aureus EDIN by the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen machinery induces vascular permeability. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3596–3601. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00186-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David S, et al. Effects of a synthetic PEG-ylated Tie-2 agonist peptide on endotoxemic lung injury and mortality. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L851–L862. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00459.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran M, et al. PGC-1α promotes recovery after acute kidney injury during systemic inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4003–4014. doi: 10.1172/JCI58662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moayeri M, et al. The heart is an early target of anthrax lethal toxin in mice: A protective role for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000456. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann M, Noack D, Wood M, Perego M, Knaus UG. Lung epithelial injury by B. anthracis lethal toxin is caused by MKK-dependent loss of cytoskeletal integrity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolcome RE, 3rd, Chan J. Constitutive MEK1 activation rescues anthrax lethal toxin-induced vascular effects in vivo. Infect Immun. 2010;78:5043–5053. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00604-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wainwright MS, et al. Protein kinase involved in lung injury susceptibility: Evidence from enzyme isoform genetic knockout and in vivo inhibitor treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6233–6238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031595100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warfel JM, D’Agnillo F. Anthrax lethal toxin-mediated disruption of endothelial VE-cadherin is attenuated by inhibition of the Rho-associated kinase pathway. Toxins (Basel) 2011;3:1278–1293. doi: 10.3390/toxins3101278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daly C, et al. Angiopoietin-1 modulates endothelial cell function and gene expression via the transcription factor FKHR (FOXO1) Genes Dev. 2004;18:1060–1071. doi: 10.1101/gad.1189704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daly C, et al. Angiopoietin-2 functions as an autocrine protective factor in stressed endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15491–15496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607538103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Palma M, et al. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley KA, Mogridge J, Mourez M, Collier RJ, Young JA. Identification of the cellular receptor for anthrax toxin. Nature. 2001;414:225–229. doi: 10.1038/n35101999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scobie HM, Rainey GJ, Bradley KA, Young JA. Human capillary morphogenesis protein 2 functions as an anthrax toxin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5170–5174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0431098100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeo TW, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is associated with decreased endothelial nitric oxide and poor clinical outcome in severe falciparum malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17097–17102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805782105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Negrete OA, et al. EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature. 2005;436:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavrilovskaya IN, Shepley M, Shaw R, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER. beta3 Integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7074–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th Ed. Washington, DC: National Academies; 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.