Abstract

Isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (Icmt) methylates the carboxyl-terminal isoprenylcysteine of CAAX proteins (e.g., Ras and Rho proteins). In the case of the Ras proteins, carboxyl methylation is important for targeting of the proteins to the plasma membrane. We hypothesized that a knockout of Icmt would reduce the ability of cells to be transformed by K-Ras. Fibroblasts harboring a floxed Icmt allele and expressing activated K-Ras (K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx) were treated with Cre-adenovirus, producing K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts. Inactivation of Icmt inhibited cell growth and K-Ras–induced oncogenic transformation, both in soft agar assays and in a nude mice model. The inactivation of Icmt did not affect growth factor–stimulated phosphorylation of Erk1/2 or Akt1. However, levels of RhoA were greatly reduced as a consequence of accelerated protein turnover. In addition, there was a large Ras/Erk1/2-dependent increase in p21Cip1, which was probably a consequence of the reduced levels of RhoA. Deletion of p21Cip1 restored the ability of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts to grow in soft agar. The effect of inactivating Icmt was not limited to the inhibition of K-Ras–induced transformation: inactivation of Icmt blocked transformation by an oncogenic form of B-Raf (V599E). These studies identify Icmt as a potential target for reducing the growth of K-Ras– and B-Raf–induced malignancies.

Introduction

Proteins that terminate with a carboxyl-terminal “CAAX” motif, such as the Ras and Rho proteins, undergo three sequential posttranslational processing events. First, the cysteine (i.e., the C of the CAAX sequence) is isoprenylated by protein farnesyltransferase (FTase) or geranylgeranyltransferase type I (GGTase I) (1). Second, the last three amino acids of the protein (i.e., the -AAX) are cleaved off by Rce1, an integral membrane protein of the ER (2). Third, the newly exposed isoprenylcysteine is methylated by an ER membrane–bound methyltransferase, isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (Icmt) (3). These modifications render the C terminus of CAAX proteins more hydrophobic, facilitating binding to membranes (4–6).

The posttranslational processing of CAAX proteins has attracted interest because of the central role of mutationally activated Ras proteins in the development of cancer (7, 8). The enzymes that carry out the posttranslational modifications of CAAX proteins (i.e., FTase, GGTase I, Rce1, and Icmt) have been considered as potential targets for modulating the activity of the Ras proteins and for blocking the growth of Ras-induced malignancies. Farnesylation is critical for Ras activity (9), and farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) have shown promise in treating tumors, both in experimental animals (10, 11) and in humans (12–17).

A potential drawback of the clinical use of FTIs is that K-Ras and N-Ras—the isoforms most often mutated in human tumors—can be efficiently geranylgeranylated in the setting of FTI therapy (18, 19). This alternate prenylation of the Ras proteins could limit the efficacy of FTIs in the treatment of Ras-induced tumors. The existence of an alternate means for prenylation has led several groups to focus on the postisoprenylation steps mediated by Rce1 and Icmt, since those steps are shared by farnesylated and geranylgeranylated CAAX proteins (6). We previously generated Rce1-knockout mice and found that they died quite late in gestation, after all of the major organ systems were formed (20). The Ras proteins in Rce1-deficient fibroblasts were mislocalized away from the plasma membrane, and the cells grew slightly slower than wild-type cells (20). More recently, we showed that the inactivation of Rce1 partially blocked transformation of cells by an activated form of H-Ras or K-Ras and sensitized transformed cells to the antiproliferative effects of an FTI (21).

The phenotype of Icmt deficiency in mice was more severe than Rce1 deficiency; an Icmt knockout caused grossly retarded growth during embryonic development and death at embryonic day 10.5–11.5 (22), possibly due to agenesis of the liver (23). Icmt deficiency causes mislocalization of the Ras proteins within cells, but virtually nothing is known about the effects of Icmt deficiency on cell growth and oncogenic transformation. To address these issues, we created a conditional (“floxed”) Icmt allele, generated fibroblast cell lines, and then analyzed the consequences of inactivating Icmt.

Methods

Production of a conditional Icmt allele.

To generate a conditional Icmt allele, exon 1 of Icmt along with upstream promoter sequences and parts of intron 1 were flanked with loxP sites. A 5′ arm of the gene-targeting vector (4 kb in length) was amplified from bacterial artificial chromosome DNA (24) with primers 5′-CTCTGTGCGGCCGCCTGTGTATAACTGTTTCCTTAGGTATG-3′ and 5′-ACGACGGCGGCCGCCCGGCGACGCCGGCTCGGGAAGGGC-3′ and cloned into the NotI site of pKSloxPNT (25). A 2.1-kb 3′ arm was amplified with primers 5′-ACGACGGCGGCCGCAGGGTAGGTGCACCAGGTACATTAGAACCG-3′ and 5′-ACGACGGAATTCCTTCAGTTCTGGCCAGAAGATGTTGTCGAGCG-3′ and cloned into the polylinker EcoRI site. A 717-bp fragment containing promoter sequences, exon 1, and parts of intron 1 was amplified with 5′-ACGACTATCGATTTGAATGCGCAGGCCGGCCTTCGGGTTTCCC-3′ and 5′-ACGACGGCGGCCGCATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATGCCCCATCCCTGACTGATCGGTCCCTG-3′, which contained a loxP site. That fragment was inserted between the polylinker ClaI and BamHI sites. The vector was linearized with XhoI and electroporated into 129SV/Jae ES cells. ES cells were screened by Southern blotting; the genomic DNA was cleaved with BamHI, and the blots were hybridized with a 292-bp 5′-flanking probe (24). Two targeted clones, each with a single integration event, were used to generate germline-transmitting chimeric mice.

Primary fibroblasts were isolated from Icmtflx/flx embryos on day 15.5 post coitum (20, 26). The cells were immortalized with a modified 3T3 protocol (26) or by transfecting the cells with E1A and activated human K-Ras (with a G12V activating mutation) (21, 27, 28). For some experiments, the fibroblasts were also infected with a retrovirus encoding human K-Ras (G12V) and a puromycin-resistance cassette. Experiments were performed with two different K-Ras–transfected Icmtflx/flx cell lines (A and B), unless otherwise indicated. To produce B-Raf–transformed cell lines, spontaneously immortalized Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts were transfected with a retrovirus encoding an oncogenic form of human B-Raf (V599E) and a blasticidin-resistance cassette. Control cells were infected with a retrovirus encoding wild-type B-Raf. To inactivate Icmt (to produce IcmtΔ/Δ cells), Icmtflx/flx cells were infected with 108 PFU/ml of Cre-adenovirus (AdRSVCre). In parallel, control Icmtflx/flx cells were treated with 108 PFU/ml of a β-gal adenovirus (AdRSVnlacZ). The efficiency of Cre-mediated recombination was assessed with Southern blotting. All experiments with IcmtΔ/Δ cells were initiated three to four passages after the AdRSVCre infection. To produce mixed populations of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells, Icmtflx/flx cells were infected with low titers of AdRSVCre (106 PFU/ml) and high titers (108 PFU/ml) of AdRSVnlacZ (so that all of the cells in the dish would be infected with adenovirus).

Icmt activity assay.

Icmt activity was measured with base-hydrolysis assays with S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-14C]methionine as the methyl donor and either N-acetyl-S-geranylgeranyl-L-cysteine or farnesyl-K-Ras as the substrate. The accumulation of “methylatable substrates” in cell extracts was quantified by measuring the methylation of proteins in cell extracts in the presence of recombinant Ste14p (the yeast ortholog of Icmt) and S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-14C]methionine (24).

Analyzing fibroblast growth.

Anchorage-dependent growth was assessed with a tetrazolium compound (MTS)–based cell proliferation assay (Cell Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay; Promega Corp., Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells were seeded on 96-well plates (500 or 1,000 cells/well, n = 12 wells/cell line, 1 plate per time point) and incubated at 37°C. At various time points, 20 μl of the MTS reagent ([3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)]-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Cell density was quantified by analyzing absorbance at 490 nm. The relative growth rates of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells also were assessed with Southern blots to compare the relative intensities of Icmtflx and IcmtΔ bands at different passages. Cells were passaged 1:10 every 4 days; the intensities of bands on Southern blots were quantified with a phosphorimager.

Analyzing growth of hepatocytes in vitro.

To fully inactivate Icmt in the liver (i.e., obtain nearly complete levels of recombination in the liver), Icmtflx/flx mice harboring the inducible Mx1-Cre transgene (29) were injected intraperitoneally with polyinosinic-polycytidylic ribonucleic acid (pI-pC; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) (300 μg every other day for a total of four injections). To generate mice with partial recombination in the liver (i.e., mice whose livers contained a mixture of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes), mice were given a single pI-pC injection (200–500 μg). In the latter mice, the relative rates of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cell proliferation were assessed after a partial hepatectomy (30). To gain insight into the relative growth rates of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes, Southern blotting was used to compare the ratio of Icmtflx and IcmtΔ alleles at the time of partial hepatectomy and 10 days later, when liver regeneration was complete.

Analysis of anchorage-independent growth.

The ability of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts to form colonies in soft agar was analyzed in side-by-side experiments. For these studies, K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were produced from K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts with AdRSVCre (108 PFU/ml). Control K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts were infected with 108 PFU/ml of AdRSVnlacZ. The K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts (500–10,000 cells) were placed in medium containing 0.35% agarose and then poured onto 12-well plates containing a 0.70% agarose base. After the plates had been incubated at 37°C for 21–30 days, the colonies were stained with 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (thiazolyl blue, MTT; Sigma-Aldrich) and photographed. The number of colonies was quantified with an image-processing tool kit in Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (21).

Assay of tumorigenicity in nude mice.

To assess the relative capacities of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts to form tumors in nude mice, a mixed population of K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts was generated by treating K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts with a low-titer AdRSVCre (106 PFU/ml) as already described. Those cells (5 × 106) were injected into the flanks of 10-week-old female nude mice (strain NU/J Foxn1nu; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). The relative capacities of the K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts to contribute to tumor growth were assessed by comparing the ratios of Icmtflx and IcmtΔ alleles in the genomic DNA of the injected fibroblasts and in the tumors (harvested 21 days after injection).

Expression of human ICMT in Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts.

K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts were transfected with an expression vector (pcDNA6Myc/His-B; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA) containing the human ICMT cDNA. Blasticidin-resistant colonies were picked and expanded. Two K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx:ICMT cell lines were infected with AdRSVCre, generating K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ:ICMT cell lines. The K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx:ICMT and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ:ICMT cell lines expressed similar levels of Icmt enzymatic activity, indicating that most of the enzymatic activity in the cells was due to the human ICMT cDNA.

Subcellular fractionation to assess membrane targeting of the Ras proteins.

S100 (cytosolic) and P100 (membrane) fractions of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells were prepared, and Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated as described (21). Western blots were performed with a K-Ras–specific mAb (Ab-1; Oncogene Research Products, San Diego, California, USA), a HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), and the Enhanced Chemiluminescence Kit (Amersham Biosciences Corp.).

Assessment of subcellular localization of K-Ras with an enhanced GFP–truncated (EGFP-truncated) K-Ras fusion protein.

Icmt+/+ and Icmt–/– fibroblasts were transfected with a plasmid coding for a fusion between EGFP and the C-terminal 20 amino acids of K-Ras (20). Transfections were carried out with SuperFect Reagent (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, California, USA). Cells were fixed in 4% formalin 24–28 hours after transfection, mounted, and viewed with a Bio-Rad MRC-600 laser scanning confocal imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, California, USA).

Coimmunoprecipitation of p21Cip1 and cyclin A.

Cyclin A was immunoprecipitated from 1.0 mg of total cell protein from extracts of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells with a polyclonal antibody (H-432; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, California, USA) and resolved on 10–20% SDS-PAGE gels. To detect cyclin A–associated p21Cip1, immunoblots were then performed with an anti-p21Cip1 antibody (F-5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.).

Analysis of turnover of Rho and Ras proteins.

To assess the impact of the Icmt gene inactivation on Ras and Rho turnover, K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells were seeded onto 60-mm plates, grown overnight, and then grown for 2 hours in methionine-free medium. Cells were metabolically labeled with 0.8 mCi L-[35S]methionine and L-[35S]cysteine (Pro-mix L-[35S] in vitro cell labeling mix; Amersham Biosciences Corp.) for 2 hours. The cells were washed and incubated with regular medium supplemented with 4 mM methionine and cysteine. Cells were harvested at different time points, and Rho and Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated from the extracts with pan-Rho [Anti-Rho (-A, -B, -C); Upstate Biotechnology Inc., Lake Placid, New York, USA] and pan-Ras (Ab-4; Oncogene Research Products) antibodies, respectively. The proteins were resolved on 10–20% SDS-PAGE gels that were subsequently treated with Amplify (Amersham Biosciences Corp.), dried, and exposed to film for 4–7 days.

Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling.

Serum- and EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of the downstream Ras effectors Erk1/2 and Akt1 was assessed by seeding 105 nontransfected Icmtflx/flx and derivative IcmtΔ/Δ cells (i.e., no activated K-Ras) on 60-mm dishes and then subjecting them to overnight serum starvation (in 0.5% serum). The next morning, medium containing 10% serum or 50 ng/ml human EGF (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the cells. At various times after EGF stimulation, the cells were harvested and total cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing phospho-Erk1/2 (phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase E10 mAb; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA), phospho-Akt1 [(Ser 473)-R, polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.], and total Erk1/2 (p44/42 MAP kinase, polyclonal; Cell Signaling Technology).

Northern blotting and cDNA probes.

Northern blots were performed with standard techniques (31) on total cellular RNA extracted with the TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). A mouse Kras2 cDNA probe was amplified from a mouse liver cDNA library (CLONTECH Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, California, USA) with forward primer 5′-AAAGCGGAGAGAGGCCTGCTGAAAATG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ACCATAGGCACATCTTCAGAGTCC-3′. A mouse RhoA (Ahra2) cDNA probe was amplified from the mouse liver cDNA library with forward primer 5′-ACTGGTGATTGTTGGTGATGGAGC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TCATTCCGAAGGTCCTTCTTGTTCCC-3′. A mouse p21Cip1 (Cdkn1a) cDNA probe was amplified from the mouse liver cDNA library with forward primer 5′-AAAAGCACCTGCAAGACCAGAGGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TTAAGTTTGGAGACTGGGAGAGGG-3′.

Generation of Cdkn1a-deficient Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cell lines.

Male p21Cip1-deficient mice (Cdkn1a–/–) (32) (provided by Allan Balmain, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA) were bred with Icmtflx/flx mice. Icmt+/flx Cdkn1a+/– mice were intercrossed and embryonic fibroblasts were harvested 15.5 days post coitum. Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– spontaneously immortalized fibroblasts were infected with a retrovirus expressing the activated human K-Ras. K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts were treated with AdRSVCre (108 PFU/ml) to generate K-Ras-IcmtΔ/ΔCdkn1a–/– cells. Control K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts were treated with AdRSVnlacZ (108 PFU/ml).

Results

Creation of Icmt-deficient fibroblast cell lines.

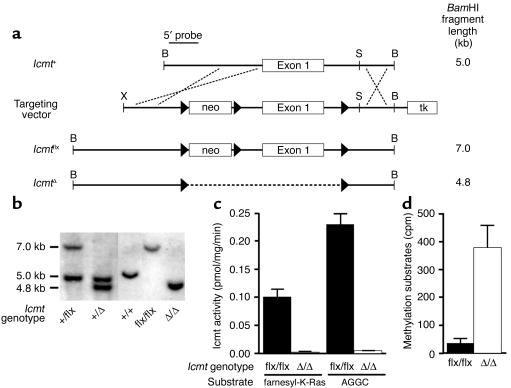

To assess the importance of Icmt for cell growth and Ras transformation, we created a conditional Icmt-knockout allele in which exon 1 and upstream promoter sequences were flanked by loxP sites (Figure 1a). Two independent ES cell lines (each with a single neo integration) were used to create chimeric mice, which were bred to produce heterozygous mice (Icmt+/flx). When Icmt+/flx mice were intercrossed, homozygous mice (Icmtflx/flx) were born at the predicted mendelian frequency and were fertile and healthy. Fibroblasts from Icmtflx/flx embryos were immortalized as described in the Methods section. Cre-mediated excision of the floxed segment of Icmt resulted in the production of IcmtΔ/Δ cells (Figure 1b). Not surprisingly, IcmtΔ/Δ cells exhibited both a complete absence of Icmt enzymatic activity (Figure 1c) and a substantial accumulation of Icmt protein substrates (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Generation and validation of a conditional Icmt allele (Icmtflx). (a) A sequence-replacement gene-targeting vector designed to flank exon 1 and upstream sequences with loxP sites. tk, thymidine kinase. (b) Southern blot identification of the Icmt+, Icmtflx, and IcmtΔ alleles with BamHI-cleaved genomic DNA and the 5′-flanking probe. (c) Icmt activity in extracts of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, as judged by a base-hydrolysis vapor-diffusion assay. Assays used S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-14C]methionine as the methyl donor and either farnesyl-K-Ras or N-acetyl-S-geranylgeranyl-L-cysteine (AGGC) as substrates. Bar graphs show the mean of two independent cell lines in two independent experiments. (d) Accumulation of Icmt substrates in IcmtΔ/Δ cells. Recombinant yeast Ste14p was added to extracts of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells along with S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-14C]methionine; methylation of protein substrates was measured with the base-hydrolysis vapor-diffusion assay.

Icmt-deficient fibroblasts grow slowly.

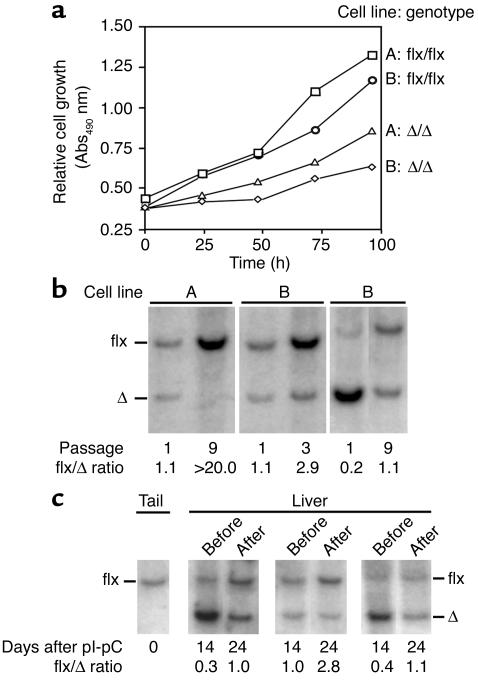

The inactivation of Icmt in immortalized fibroblasts reduced cell growth by 40–60% under routine cell culture conditions (anchorage-dependent growth) (Figure 2a). To further examine the consequences of “switching off” Icmt, we produced mixed populations of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells by treating Icmtflx/flx cells with low titers (106 PFU/ml) of AdRSVCre and high titers (108 PFU/ml) of AdRSVnlacZ (so that all of the cells were infected with an adenovirus). We then initiated competitive growth experiments to define the relative growth rates for Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells. For this, Southern blots were used to assess the ratio of the 7.0-kb Icmtflx band and the 4.8-kb IcmtΔ band (Figure 2b). If the Icmt inactivation had no effect on cell growth (i.e., if there were no differences in the competitive fitness of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells), one would expect that the Southern blots would reveal stability—at different passages—in the relative intensities of the Icmtflx and IcmtΔ bands. This was not the case. In each experiment, the ratio of the Icmtflx band to the IcmtΔ band increased in later passages, indicating a competitive growth advantage of the parental Icmtflx/flx cells over the IcmtΔ/Δ cells (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Analyzing the effect of Icmt inactivation on cell growth. (a) Anchorage-dependent growth of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells. Equal numbers of immortalized Icmtflx/flx cells and the derivative IcmtΔ/Δ cells (lines A and B) were plated onto 96-well plates (n = 12 wells per cell line), and cell growth was assessed with the Cell Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega). (b) Southern blots illustrating the increase in the ratio of Icmtflx to IcmtΔ bands during the growth of a mixed population of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells. Mixed populations of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells were passaged at a 1:10 ratio every 3 days. DNA was harvested and analyzed with Southern blots at the indicated passages. (c) Southern blot of liver DNA from three Icmtflx/flxMx1-Cre mice before and after hepatocyte proliferation, which was induced by a partial hepatectomy. The ratio of Icmtflx to IcmtΔ band intensity increased after liver regrowth, indicating that Icmtflx/flx hepatocytes contributed more to liver regrowth than the IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes. Quantification of data from five mice revealed that the Icmtflx/IcmtΔ ratio increased 201% ± 26% after liver regeneration (P < 0.01).

Inactivating Icmt also interfered with the growth of hepatocytes in vivo. We bred Icmtflx/flx mice with mice harboring the inducible Mx1-Cre transgene and then administered a single intraperitoneal injection of pI-pC. A single pI-pC injection causes incomplete recombination in the liver; thus, the livers of these mice contained a mixed population of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes. Two weeks later, we performed a partial hepatectomy, which triggers hepatocyte proliferation. To gauge the relative capacities of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes to contribute to liver regeneration, we used Southern blots to measure the ratio of the 7-kb Icmtflx band to the 4.8-kb IcmtΔ band in liver genomic DNA, both at baseline (at the time of the partial hepatectomy) and 10 days later when liver regeneration was complete. After liver regeneration, the ratio of the Icmtflx band to the IcmtΔ band invariably increased, indicating that Icmtflx/flx hepatocytes contributed more than the IcmtΔ/Δ hepatocytes to liver regrowth (Figure 2c; P < 0.01, n = 5). This difference could not be attributed to hepatocyte death due to the Icmt knockout. By treating Icmtflx/flx mice with four intraperitoneal injections of pI-pC, we readily generated mice in which Cre-mediated recombination in the liver was virtually complete. In those mice, plasma transaminases remained normal, and there was no histological evidence of hepatocyte necrosis (not shown).

Inhibition of K-Ras transformation in Icmt-deficient cells.

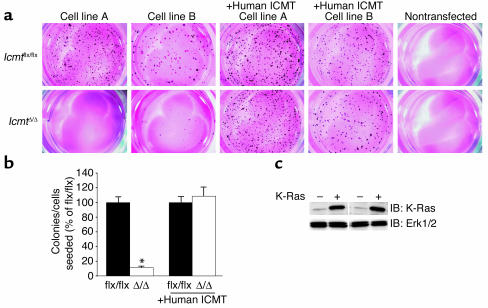

Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts that had been transfected with an activated form of K-Ras (K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx) exhibited a transformed phenotype, forming numerous colonies in soft agar (Figure 3a). To assess the consequences of Icmt deficiency on K-Ras transformation, we then used AdRSVCre to inactivate Icmt in the K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells, producing K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cell lines. In six independent side-by-side experiments, the K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells yielded 90–95% fewer colonies in soft agar than the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells (Figure 3, a and b, P < 0.0001). When these experiments were repeated with K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells that expressed a human ICMT cDNA, AdRSVCre inactivation of the mouse Icmt gene had no detectable effect on colony growth (Figure 3, a and b, n = three independent experiments, P = 0.63). Thus, inactivation of Icmt strikingly inhibited the ability of K-Ras–transfected cells to grow in soft agar — except when the cells had been transfected with human ICMT. Similar data were obtained in experiments with fibroblasts from conventional Icmt knockout embryos (Icmt–/–) and littermate Icmt+/+ controls. After immortalization of the fibroblasts and K-Ras transfection, the Icmt+/+ fibroblasts, but not the Icmt–/– fibroblasts, formed colonies in soft agar (n = five independent Icmt–/– and n = three independent Icmt+/+ cell lines) (not shown).

Figure 3.

Reduced capacity of K-Ras–transfected Icmt-deficient fibroblasts to form colonies in soft agar. (a) K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts (2,000 cells of each) were mixed with 0.35% agarose and poured onto plates containing a 0.70% agarose base. Colonies were stained and photographed 21 days later. Nontransfected cells (i.e., no activated K-Ras) did not form colonies in soft agar. (b) Bar graph illustrating the number of colonies formed in soft agar in four independent experiments; data in each experiment were normalized to the number of colonies that formed with the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts. Inactivation of Icmt significantly reduced the number of colonies that formed in soft agar (*P < 0.0001). For experiments involving K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx:ICMT cells (expressing a human ICMT cDNA) and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ:ICMT cells, data show the results from three independent experiments. In the cells expressing human ICMT, inactivation of mouse Icmt did not affect colony formation (P = 0.63). (c) Western blot showing higher K-Ras expression levels in K–Ras-transfected cells (+) compared with nontransfected cells (–). The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control. IB, immunoblot.

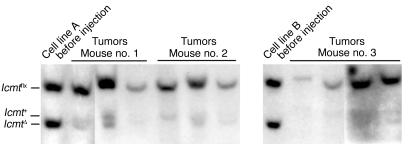

To assess the consequences of Icmt deficiency on tumor cell growth in vivo, mixed populations of K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells (produced by treating K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells with a low titer of AdRSVCre and a high titer of AdRSVnlacZ) were injected subcutaneously into nude mice, and tumors were harvested 21 days later. The ratio of the Icmtflx band to the IcmtΔ band in the injected cell mixture was 1.1 ± 0.2, reflecting nearly equal numbers of Icmtflx/flx and IcmtΔ/Δ cells (Figure 4). In the tumors, the ratio of the Icmtflx band to the IcmtΔ band was 15.2 ± 2.2 (Figure 4, n = 10 tumors), indicating that it was mainly the Icmtflx/flx cells that contributed to tumor growth.

Figure 4.

Impaired ability of K-Ras–transfected Icmt-deficient fibroblasts to contribute to tumor growth in nude mice. A mixed population of K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells and derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells (total of 500,000 cells, prepared as described in the Methods section) was injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Tumors were harvested 21 days later. Southern blots were performed on genomic DNA prepared from the injected cells and the tumors. The ratio of Icmtflx to IcmtΔ band intensity was much greater in the tumor DNA than in the injected cells. A 5-kb Icmt+ allele in some lanes was due to host DNA in the tumors.

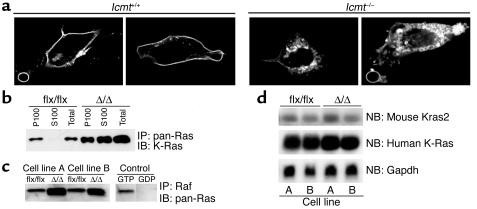

Ras proteins in IcmtΔ/Δ cells are mislocalized, but Erk and Akt phosphorylation are unaffected.

A GFP–K-Ras fusion protein was mislocalized in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts (Figure 5a). Also, a large portion of the K-Ras in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts was present in the soluble (S100) fraction of cells, whereas nearly all of the K-Ras in the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts was associated with the membrane (P100) fraction (Figure 5b). Notably, inactivation of Icmt in the K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts invariably caused about a twofold increase in steady-state levels of total Ras proteins and GTP-bound Ras proteins within cells (Figure 5, b and c), while the ratio of total to GTP-bound Ras remained constant (not shown). The higher levels of the Ras proteins could not be explained by higher levels of mouse K-Ras or human K-Ras mRNA (Figure 5d) and are apparently due to a decreased turnover of Ras in these cells (see later).

Figure 5.

Mislocalization and increased steady-state levels of K-Ras in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts. (a) Confocal micrographs of spontaneously immortalized Icmt+/+ and Icmt–/– fibroblasts that had been transfected with a GFP–K-Ras fusion construct. (b) Distribution of Ras proteins in the membrane (P100) and cytosolic (S100) fractions of K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts. The Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated from 1,000 μg of the indicated cell fractions with a pan-Ras–specific antibody, and a Western blot was performed with a K-Ras–specific antibody. (c) GTP-bound Ras proteins in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts. GTP-bound Ras proteins were precipitated from 1 × 106 K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells with the Ras-binding domain of Raf (Ras Activation Kit; Upstate Biotechnology Inc.), and a Western blot was performed with a pan-Ras antibody. (d) Northern blot of total RNA from K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, hybridized with a mouse Kras2 cDNA probe. That probe detects a longer mouse Kras2 transcript (upper panel) and a shorter human activated K-Ras transcript (middle panel). The blot was stripped and hybridized with a Gapdh cDNA probe (lower panel). IP, immunoprecipitation; NB, Northern blot.

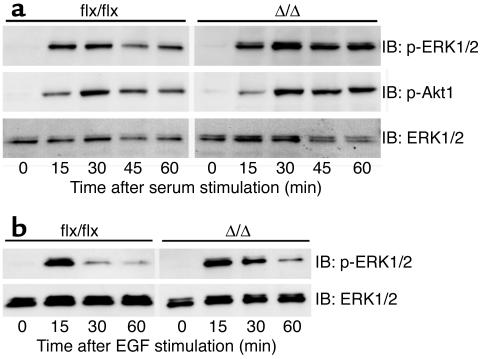

The inactivation of Icmt in nontransfected cells (i.e., no activated K-Ras) did not affect serum growth factor–stimulated or EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of the downstream Ras effectors, Erk1/2 and Akt1 (Figure 6, a and b). These results indicate that the absence of carboxyl methylation of CAAX proteins in Icmt-deficient cells has prominent effects on Ras targeting to membranes and on the steady-state levels of Ras proteins in cells, but apparently little or no effect on the growth factor–stimulated activation of Erk1/2 and Akt.

Figure 6.

Growth factor-stimulated Erk1/2 and Akt1 phosphorylation in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts. (a) Nontransfected Icmtflx/flx and the derivative IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were seeded at equal density and serum-starved overnight as described in the Methods section. Serum-containing medium was then added to the cells. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated Erk1/2 (p-Erk1/2), phosphorylated Akt1 (p-Akt1), and total Erk1/2. (b) Icmtflx/flx and the derivative IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were seeded at equal density and serum-starved overnight. Medium (0.5% serum) supplemented with EGF (50 ng/ml) was added to the cells. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against p-Erk1/2 and total Erk1/2.

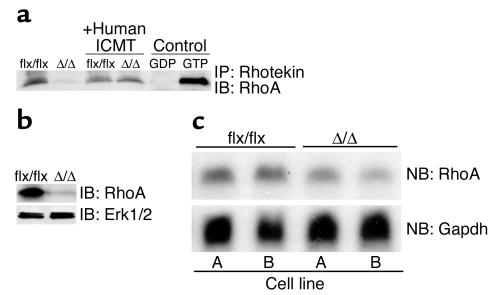

Accelerated turnover of Rho proteins in IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts.

The Rho GTPases play important roles in cell-cycle progression and cell transformation (33–35). Rho proteins are CAAX proteins that, like the Ras proteins, undergo Icmt-mediated methylation. We hypothesized that the slow growth of IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts and their resistance to K-Ras transformation might be accompanied by a defect in Rho metabolism and signaling. Indeed, our data suggest that this was the case. The steady-state levels of total RhoA and GTP-bound RhoA in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were only about 5–10% of those in the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells (Figure 7, a and b, P < 0.001). This finding was clearly due to absence of Icmt activity, since K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts expressing the human ICMT cDNA exhibited normal levels of GTP-bound RhoA (Figure 7a). The low levels of RhoA protein in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were not accompanied by a comparable reduction in the levels of RhoA mRNA (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Low steady-state levels of RhoA in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts. (a) GTP-bound Rho proteins were immunoprecipitated from 1 × 106 K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts with equal amounts of Rhotekin-GST (Rho Activation Kit; Upstate Biotechnology Inc.). The GTP-bound Rho proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected with a RhoA-specific antibody (26C4 monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). In the same experiment, bands for two control proteins were of identical intensity in the K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts (not shown). Similar results were obtained when using a pan-Rho antibody. (b) Cell extracts from K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were analyzed by immunoblotting with a RhoA-specific antibody. The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control. (c) Northern blot (NB) of total cellular RNA from K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts was hybridized with a mouse RhoA cDNA probe. Reprobing of the membrane with a Gapdh cDNA probe revealed similar levels of Gapdh expression in each sample (see Figure 5d).

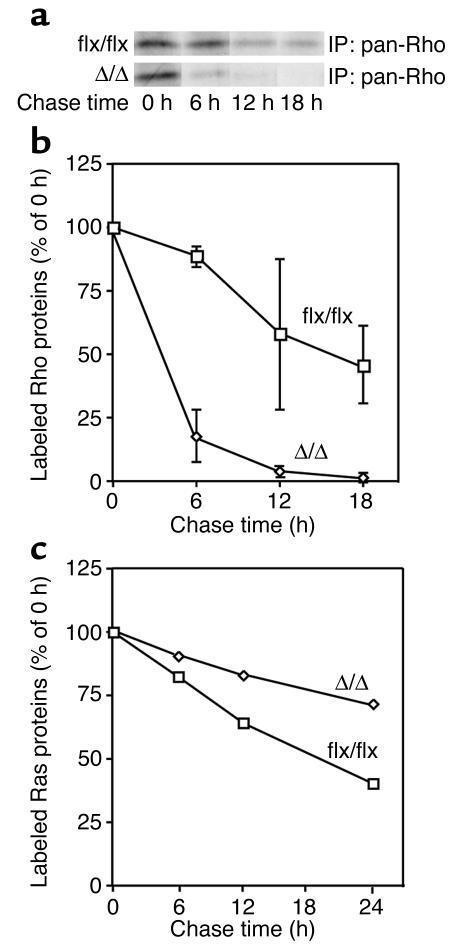

To determine if accelerated Rho turnover was responsible for the low levels of RhoA in the K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, we used metabolic labeling/pulse-chase experiments to assess the half-life of Rho proteins in cells. In four separate experiments, Rho proteins disappeared more quickly in the K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells than in the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells (Figure 8, a and b) (Rho half-life, 22.0 ± 9.4 hours in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells and 2.8 ± 0.4 hours in the K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells). Notably, the absence of methylation retarded Ras turnover within cells (Figure 8c) (Ras half-life, 13.9 ± 6.1 hours in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells and 32.5 ± 6.0 hours in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells), probably explaining the differences in steady-state levels of Ras proteins in Figure 5, b and c. Thus, the absence of carboxyl methylation is associated with accelerated turnover of the Rho proteins but retarded turnover of the Ras proteins.

Figure 8.

Accelerated turnover of Rho proteins in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts. (a) K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine for 2 hours and then incubated in regular medium supplemented with 4 mM “cold” methionine and cysteine for the indicated times. Rho proteins were immunoprecipitated from total cell extracts with a pan-Rho antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and then visualized by autoradiography as described in the Methods section. (b) Pulse-chase analysis of Rho protein disappearance in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts. Graphs show mean densitometry results from three independent experiments. (c) Pulse-chase analysis of Ras proteins in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts. Ras proteins were immunoprecipitated from total cell extracts with a pan-Ras antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and then visualized by autoradiography. Graphs show mean densitometry data from two independent experiments.

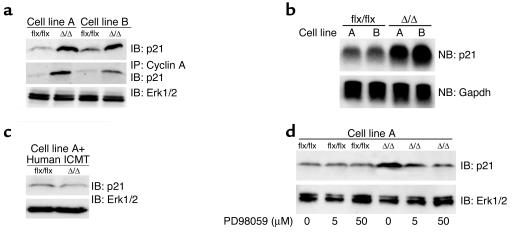

Upregulation of p21Cip1 in K-Ras-transfected IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts.

The regulatory protein p21Cip1 binds to cyclins and inhibits cell-cycle progression (35, 36). p21Cip1 levels are upregulated by overexpression of activated Ras, but this Ras-induced upregulation can be antagonized by RhoA (32, 34). In light of the low levels of RhoA in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, we hypothesized that those cells might exhibit higher levels of p21Cip1. Indeed, p21Cip1 levels in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells were more than fourfold higher in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells than in the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells (Figure 9a, P < 0.01). The increase in p21Cip1 protein levels in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts was accompanied by a 1.4-fold increase in p21Cip1 mRNA levels (Figure 9b, P < 0.001). The increase in p21Cip1 protein levels was not observed in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ cells expressing a human ICMT cDNA (Figure 9c). The increased level of p21Cip1 in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts was accompanied by an increased association between p21Cip1 and cyclin A (Figure 9a, middle panel). To test whether signaling through the Erk1/2 pathway was involved in the upregulation of p21Cip1, we treated K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts and the parental K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells with the MEK inhibitor PD98059. PD98059 decreased p21Cip1 levels in the K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, but it did not affect p21Cip1 levels in the K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts (Figure 9d). This result does not prove that Ras signaling is involved in the upregulation of p21Cip1. However, in nontransfected IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts, the levels of p21Cip1 were similar to those in the parental Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts (not shown). These data suggest that increased Ras signaling through the Erk1/2 pathway could be responsible for the upregulation of p21Cip1 in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts.

Figure 9.

Increased p21Cip1 protein levels in Icmt-deficient fibroblasts. (a) Extracts from K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody recognizing p21Cip1 (F-5 monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) (upper panel). Cyclin A was immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts with a polyclonal antibody (H-432; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), and cyclin A–associated p21Cip1 was detected by immunoblotting (middle panel). The blot from the upper panel was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control (lower panel). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (b) Northern blot of total cellular RNA showing p21Cip1 (Cdkn1a) mRNA levels in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts (upper panel). The blot was stripped and probed with a Gapdh cDNA probe as a loading control (lower panel). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (c) Immunoblot showing p21Cip1 protein levels in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx:ICMT fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ:ICMT fibroblasts. The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control (lower panel). (d) K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were treated overnight with the MEK inhibitor PD98059, and extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with a p21Cip1-specific antibody. The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control (lower panel).

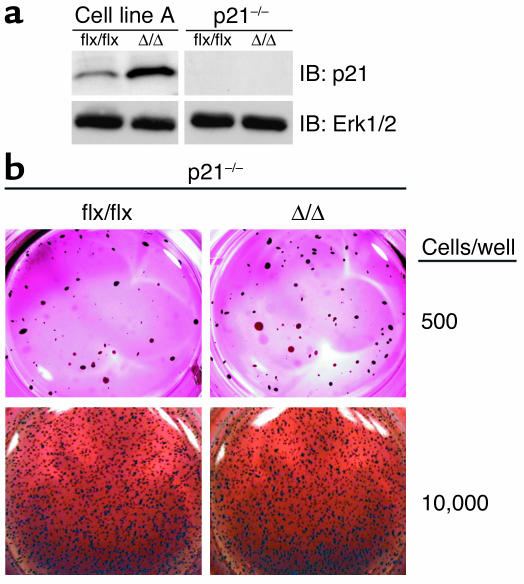

Knocking out p21Cip1 restores the capacity of K-Ras-transfected IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts to grow in soft agar.

The finding that p21Cip1 levels were elevated in K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts suggested that p21Cip1 might be important for the markedly reduced oncogenic capacity of these cells. To test this hypothesis, we generated p21Cip1-deficient K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts and then used AdRSVCre to produce p21Cip1-deficient K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts (Figure 10a). In the absence of p21Cip1, the inactivation of Icmt no longer blocked the ability of K-Ras–transfected cells to grow in soft agar (Figure 10b). Similarly, in the absence of p21Cip1, there was no difference in the growth rate of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ and K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts under routine cell-culture conditions (anchorage-dependent growth) (not shown).

Figure 10.

Knocking out p21Cip1 restores the capacity of K-Ras-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts to grow in soft agar. (a) Western blot showing the absence of p21Cip1 protein in K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/ΔCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts. The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control (lower panel). (b) K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– and K-Ras-IcmtΔ/ΔCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts were seeded in soft agar. After 30 days, the colonies were stained, photographed, and analyzed as described in the Methods section. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments; there was no difference in colony numbers with K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/– and the derivative K-Ras-IcmtΔ/ΔCdkn1a–/– fibroblasts (P = 0.47).

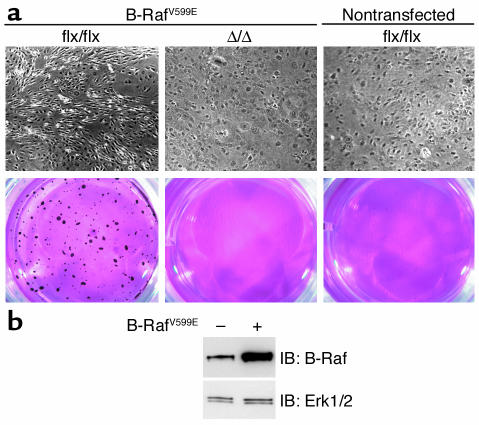

Inactivation of Icmt blocks B-Raf-induced cellular transformation.

To determine if the effect of the Icmt inactivation was limited to inhibiting the growth of K-Ras–transformed fibroblasts, we analyzed the effect of inactivating Icmt in Icmtflx/flx cells that had been infected with a retrovirus encoding a mutationally activated form of human B-Raf (V599E). B-Raf-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts grew faster than nontransfected cells, lost contact inhibition, and were capable of forming colonies in soft agar (Figure 11). AdRSVCre-mediated deletion of Icmt from B-Raf-Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts (to produce B-Raf-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts) restored contact inhibition and eliminated the ability of the cells to grow in soft agar (Figure 11). In addition, B-Raf–transfected Icmt–/– fibroblasts did not form colonies in soft agar, whereas B-Raf–transfected Icmt+/+ fibroblasts did (not shown).

Figure 11.

Inactivation of Icmt reverses B-Raf–induced transformation. (a) B-Raf-Icmtflx/flx and B-Raf-IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts were grown to confluence and then allowed to grow for an additional 6 days. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and photographed (upper panel). An aliquot of the same cells was seeded in soft agar (lower panel). After 20 days, the colonies were stained, photographed, and analyzed as described in the Methods section. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Transfection of fibroblasts with a retrovirus encoding wild-type B-Raf did not yield a transformed phenotype (not shown). (b) Western blot with a B-Raf–specific mAb (F-7; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) showing increased B-Raf expression in Icmtflx/flx fibroblasts transfected with the retrovirus encoding human B-RafV599E. The blot was stripped and incubated with an anti-Erk1/2 antibody as a loading control (lower panel).

Discussion

In the current study, we show that inactivation of Icmt in mouse fibroblasts results in slow growth and a striking reduction in oncogenic transformation induced by K-Ras and B-Raf. For the K-Ras–transfected fibroblasts we also provide evidence that the absence of carboxyl methylation results in a rapid turnover of RhoA and an upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21Cip1. These phenotypes were abrogated by the ectopic expression of a human ICMT cDNA. In addition, the finding that deletion of Cdkn1a (the gene encoding p21Cip1) abolished the effects of the Icmt inactivation on cell growth and K-Ras–induced colony formation in soft agar, suggests that the Icmt knockout–mediated inhibition of cell growth and K-Ras transformation requires p21Cip1.

Cre-mediated inactivation of Icmt caused a 90–95% reduction in K-Ras–induced colony growth in soft agar and a reduced capacity to contribute to tumor growth in nude mice. This phenotype is almost certainly due to inactivation of Icmt rather than to an artifact related to adenoviral infection—for several reasons. First, all of the control cells for these experiments were treated with an adenovirus encoding β-gal. Second, the adenovirus treatment was temporally remote from the actual experiments; all of the transformation experiments were performed at least three or four passages—more than 20 cell divisions—after adenoviral infection. Third, Cre-mediated inactivation of Icmt had no detectable effects in cells that had been previously transfected with a cDNA encoding human ICMT. Fourth, we obtained very similar cell growth and transformation results with conventional Icmt-knockout fibroblasts (Icmt–/– cells), which were not treated with adenovirus. Finally, we previously showed that Cre-adenovirus infection, under the conditions used here, did not change the growth rate of fibroblasts (21).

It is widely believed that targeting of Ras proteins to the plasma membrane is very important for downstream signaling cascades. Icmt deficiency caused a striking mislocalization of GFP–K-Ras away from the plasma membrane, as well as a redistribution of Ras proteins to the cytosolic fraction. However, the mislocalization of K-Ras was not accompanied by detectable decreases in growth factor–stimulated activation of Erk1/2 and Akt1. We have made identical observations in Rce1-deficient cells—a striking mislocalization of Ras proteins (21) but no apparent effect on Erk1/2 signaling (E. Kim et al., unpublished observations). We do not yet fully understand why the mislocalization of Ras proteins is not accompanied by detectable changes in signaling, but several possibilities exist. First, growth factor stimulation of Erk1/2 and Akt1 in Icmt-deficient cells may simply be mediated by non-Ras pathways. Second, it is possible that a small percentage of the Ras proteins make it to the plasma membrane in Icmt-deficient cells and that this small amount of normally targeted Ras is sufficient for the signaling “readouts”. Another possibility is that some of the Ras proteins in Icmt-deficient cells are mislocalized to the Golgi or ER membranes and that signaling occurs fairly normally from those locations. This explanation is not farfetched. It was recently shown that Ras targeted to the Golgi or ER was able to recruit Raf-1, activate the Erk pathway, and transform fibroblasts (37).

The fact that growth factor–stimulated Erk1/2 and Akt signaling was normal in the setting of Icmt deficiency prompted us to seek other explanations for the retarded cell growth and the reduced capacity of K-Ras–transfected cells to form colonies in soft agar. The Rho proteins are required for Ras transformation and are sometimes found at increased concentrations in Ras-transformed cells (35, 38). Because the Rho proteins are also substrates for Icmt, we asked whether Icmt deficiency might perturb Rho metabolism. Indeed, this was the case. The steady-state levels of GTP-bound RhoA and total RhoA were lower in the IcmtΔ/Δ fibroblasts than in the parental Icmtflx/flx cells, as a result of accelerated protein turnover. These findings were consistent with earlier results from Backlund (39). He used a combination of pulse-chase studies and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis to show that nonmethylated RhoA is less stable than the methylated form. Notably, the effect of methylation on protein stability can be very different for other CAAX proteins; the Ras proteins in IcmtΔ/Δ cells were actually more stable than the Ras proteins in Icmtflx/flx cells. In the case of the Ras proteins, one might reasonably hypothesize that normal Ras turnover occurs only at certain membrane surfaces, and that changes in Ras partitioning within the cell would have secondary effects on protein degradation. The finding of increased Ras levels is consistent with data from Holstein et al. (40). They found that Ras protein levels increase after mevalonate depletion, which inhibits isoprenylation of CAAX proteins. However, in their experiments, RhoA protein levels also increased. Thus, isoprenylation and carboxylmethylation could have opposite effects on the steady-state levels of RhoA.

Data from Olson et al. (36) suggest that constitutive Ras signaling in the absence of Rho increases p21Cip1 levels, leading to cell-cycle arrest. Microinjection of activated Ras into fibroblasts increased DNA synthesis, whereas the simultaneous microinjection of Ras and a specific Rho inhibitor (C3 exoenzyme) increased p21Cip1 and inhibited DNA synthesis (36). In our studies, the inactivation of Icmt in K-Ras–transfected fibroblasts was associated with a striking reduction in RhoA protein levels and a 4.2-fold upregulation of p21Cip1. We predicted that the upregulation of p21Cip1 might be an important influence in the reduced capacity of Icmt-deficient fibroblasts to grow in soft agar. Indeed, this seemed to be the case. When we performed experiments with K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx cells lacking p21Cip1 (K-Ras-Icmtflx/flxCdkn1a–/–), we found that Cre-mediated inactivation of Icmt had no measurable effect on cell growth on plastic plates or on the growth of colonies in soft agar. Notably, both FTase inhibitors and GGTase I inhibitors have been reported to increase p21Cip1 levels in human tumor cells (41, 42).

Our results indicate that the effect of the Icmt inactivation on K-Ras transformation may have been a consequence of its effects on Rho and p21Cip1 rather than being due to a direct effect on the intrinsic properties of K-Ras itself. To explore this issue further, we examined the consequences of inactivating Icmt in cells that had been transformed with mutationally activated B-Raf, a downstream Ras effector. Activating mutations in B-Raf have been identified in 66% of malignant melanomas (43). B-Raf is not a CAAX protein and hence not a substrate for Icmt, yet the Cre-mediated inactivation of Icmt reversed the transformed phenotypes in B-Raf–transfected cells. This finding is in keeping with the notion that the reversion of K-Ras transformation may not have been due to a direct effect on K-Ras.

The current study supports the idea that Icmt could be a therapeutic target for treating cancer. Perhaps more importantly, however, the current study has created a tool for addressing this issue. With the creation of mice harboring a conditional Icmt allele, it is now possible to test whether a deficiency in Icmt would retard tumor growth in vivo. Several groups have developed “latent oncogenes” that can be activated in vivo by expressing Cre, resulting in the formation of tumors (44, 45). In those mice, it would be of value to determine if the Cre-induced tumor development could be prevented by the simultaneous inactivation of Icmt.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Balmain for the Cdkn1a–/– mice, J. Otto for recombinant K-Ras, and G. Howard and S. Ordway for comments on the manuscript. We also thank P.A. Ambroziak, A. George, and C. Gregory for technical assistance during the early stages of this work. This work was supported in part by NIH grants HL41633, RO1 CA099506, and RO1 AR050200 (to S.G. Young), grants from the University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (to M.O. Bergo and S.G. Young), and the Swedish STINT Foundation (to M.O. Bergo).

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 513.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase (Icmt); fibroblasts harboring a “floxed” Icmt allele and expressing activated K-Ras (K-Ras-Icmtflx/flx); farnesyltransferase (FTase); geranylgeranyltransferase type I (GGTase I); farnesyltransferase inhibitor (FTI); Cre-adenovirus (AdRSVCre); β-gal-adenovirus (AdRSVnlacZ); enhanced GFP (EGFP); mitogen-activated protein (MAP); polyinosinic-polycytidylic ribonucleic acid (pI-pC).

References

- 1.Casey PJ, Seabra MC. Protein prenyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5289–5292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyartchuk VL, Ashby MN, Rine J. Modulation of Ras and a-factor function by carboxyl-terminal proteolysis. Science. 1997;275:1796–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai Q, et al. Mammalian prenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase is in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15030–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman LE, et al. Mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective in the farnesylation of Ras proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:9665–9669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiss Y, Goldstein JL, Seabra MC, Casey PJ, Brown MS. Inhibition of purified p21ras farnesyl:protein transferase by Cys-AAX tetrapeptides. Cell. 1990;62:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young, S.G., Ambroziak, P., Kim, E., and Clarke, S. 2000. Postisoprenylation protein processing: C′ (CaaX) endoproteases and isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase. In The enzymes. Volume 21. F. Tamanoi and D.S. Sigman, editors. Academic Press. San Diego, California, USA. 155–213.

- 7.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato K, et al. Isoprenoid addition to Ras protein is the critical modification for its membrane association and transforming activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:6403–6407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohl NE, et al. Inhibition of farnesyltransferase induces regression of mammary and salivary carcinomas in ras transgenic mice. Nat. Med. 1995;1:792–797. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omer CA, et al. Mouse mammary tumor virus-Ki-rasB transgenic mice develop mammary carcinomas that can be growth-inhibited by a farnesyl:protein transferase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2680–2688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashar HR, et al. The farnesyl transferase inhibitor SCH 66336 induces a G2 → M or G1 pause in sensitive human tumor cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;262:17–27. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase I inhibitors and cancer therapy: lessons from mechanism and bench-to-bedside translational studies. Oncogene. 2000;19:6584–6593. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox AD. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Potential role in the treatment of cancer. Drugs. 2001;61:723–732. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbs JB, et al. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors versus Ras inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1997;1:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliff A. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: targeting the molecular basis of cancer. . Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999; 1423:C19–C30. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamanoi F. Inhibitors of Ras farnesyltransferases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1993;18:349–353. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90072-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James G, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Resistance of K-RasBV12 proteins to farnesyltransferase inhibitors in Rat1 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:4454–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whyte DB, et al. K- and N-Ras are geranylgeranylated in cells treated with farnesyl protein transferase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:14459–14464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim E, et al. Disruption of the mouse Rce1 gene results in defective Ras processing and mislocalization of Ras within cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8383–8390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergo MO, et al. Absence of the CAAX endoprotease Rce1: Effects on cell growth and transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:171–181. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.171-181.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergo MO, et al. Isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase deficiency in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5841–5845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin X, et al. Prenylcysteine carboxylmethyltransferase is essential for the earliest stages of liver development in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:345–351. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergo MO, et al. Targeted inactivation of the isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase gene causes mislocalization of K-Ras in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17605–17610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanks M, Wurst W, Anson-Cartwright L, Auerbach AB, Joyner AL. Rescue of the En-1 mutant phenotype by replacement of En-1 with En-2. Science. 1995;269:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.7624797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zindy F, et al. Myc signaling via the ARF tumor suppressor regulates p53-dependent apoptosis and immortalization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2424–2433. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelekar A, Cole MD. Tumorigenicity of fibroblast lines expressing the adenovirus E1a, cellular p53, or normal c-myc genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1986;6:7–14. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kühn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webber EM, Wu JC, Wang L, Merlino G, Fausto N. Overexpression of transforming growth factor-α causes liver enlargement and increased hepatocyte proliferation in transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 1994;145:398–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown, T. 1993. Analysis of RNA by northern and slot blot hybridization. In Current protocols in molecular biology. Volume 1. F.M. Ausubel et al., editors. John Wiley & Sons. New York, New York, USA. 4.9.1–4.9.14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Brugarolas J, et al. Radiation-induced cell cycle arrest is compromised by p21 deficiency. Nature. 1995;377:552–557. doi: 10.1038/377552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormick F. Signal transduction: why Ras needs Rho. Nature. 1998;394:220–221. doi: 10.1038/28268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pruitt K, Der CJ. Ras and Rho regulation of the cell cycle and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2001;171:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahai E, Olson MF, Marshall CJ. Cross-talk between Ras and Rho signalling pathways in transformation favours proliferation and increased motility. EMBO J. 2001;20:755–766. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson MF, Paterson HF, Marshall CJ. Signals from Ras and Rho GTPases interact to regulate expression of p21Waf1/Cip1. Nature. 1998;394:295–299. doi: 10.1038/28425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiu VK, et al. Ras signalling on the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ncb783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zohn IM, Campbell SL, Khosravi-Far R, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Rho family proteins and Ras transformation: the RHOad less traveled gets congested. Oncogene. 1998;17:1415–1438. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Backlund PS., Jr Post-translational processing of RhoA. Carboxyl methylation of the carboxyl-terminal prenylcysteine increases the half-life of RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:33175–33180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holstein SA, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Hohl RJ. Consequences of mevalonate depletion. Differential transcriptional, translational, and post-translational up-regulation of Ras, Rap1a, RhoA, and RhoB. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10678–10682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sepp-Lorenzino L, Rosen N. A farnesyl-protein transferase inhibitor induces p21 expression and G1 block in p53 wild type tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20243–20251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogt A, Sun J, Qian Y, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. The geranylgeranyltransferase-I inhibitor GGTI-298 arrests human tumor cells in G0/G1 and induces p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1 in a p53-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27224–27229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies H, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakso M, et al. Targeted oncogene activation by site-specific recombination in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:6232–6236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]