Abstract

Circulating levels of HDL cholesterol are inversely related to the risk of atherosclerosis, and therapeutic increases in HDL reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events. A new study shows that HDL-associated lysophospholipids stimulate the production of the potent antiatherogenic signaling molecule NO by the vascular endothelium.

The risk of cardiovascular disease from atherosclerosis is inversely proportional to serum levels of HDL and the major HDL apolipoprotein apoAI (1). In fact, low HDL levels predict an increased risk of coronary artery disease independently of LDL levels, and 60–70% of major cardiovascular events cannot be prevented with current approaches focused on LDL, such as statin therapy (2). In addition, low HDL levels are particularly common in males with early-onset atherosclerosis (3). Based on these observations, prevention trials have been performed with agents such as niacin and fibrates, which raise HDL, and they indicate that modest increases in HDL independently yield a significant reduction in cardiovascular events (4–6). Thus, there is compelling evidence that HDL is not solely a marker of lower risk of cardiovascular disease but instead is a mediator of vascular health.

Up until recently the protective features of HDL had been attributed primarily to its classical function of removing cholesterol from peripheral tissues and transferring it to the liver in a process known as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). The delivery of cholesteryl ester from HDL to cells such as hepatocytes entails apoAI–mediated HDL cell surface interaction with scavenger receptor class B, member I (SR-BI), to which HDL binds with high affinity (7). Despite detailed understanding of HDL and RCT, the mechanisms by which HDL and apoAI are atheroprotective remain complex and not fully understood (8). This is particularly apparent when one considers evidence that circulating levels of HDL and apoAI do not regulate RCT (9, 10), and that individuals with homozygous deficiency in the plasma cholesteryl ester transferase protein, which enhances HDL cholesterol delivery to the liver, have decreased risk of coronary artery disease (11).

Our basic understanding of the role of HDL in vascular biology has entered a new era in the past few years as direct modes of action of HDL on vascular cells have been elucidated. In particular, it has been demonstrated that HDL causes potent stimulation of eNOS activity through binding to SR-BI, which is expressed in endothelium (12, 13). Similarly, HDL enhances endothelium- and NO-dependent relaxation in aortas from wild-type but not SR-BI–knockout mice (12). The HDL-induced increase in NO production may be critical to the atheroprotective features of HDL, as diminished bioavailablity of NO has a key role in the early pathogenesis of hypercholesterolemia-induced vascular disease and atherosclerosis (14). However, the mechanisms by which HDL activates eNOS and the physiological and pathological implications are yet to be fully clarified.

In the current issue of the JCI, Nofer and colleagues provide intriguing evidence that HDL-induced NO production may be mediated by the HDL-associated lysophospholipids sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), and lysosulfatide (LSF) (15). They demonstrate that SPC, S1P, and LSF each cause eNOS-dependent relaxation of precontracted aortic rings from mice, and that blood pressure falls following intra-arterial infusion of HDL, SPC, S1P, or LSF in rats pretreated with endothelin. The lysophospholipid receptor S1P3 was implicated in further studies of aortic rings from receptor-null mice (15). Collectively these observations suggest that lysophospholipids underlie an important component of HDL action on the vascular wall.

Features of HDL that mediate signaling to eNOS

Both human and animal studies indicate that apoAI is the apolipoprotein principally responsible for the atheroprotective features of HDL (16). In earlier studies of eNOS activation, lipid-free apoAI did not stimulate the enzyme in cultured endothelial cells, yet antibody to apoAI blocked eNOS activation by HDL in isolated endothelial plasma membranes, indicating that apoAI is necessary but not sufficient for eNOS stimulation (12). The work of Nofer and colleagues suggests that cargoes of the HDL particle, namely SPC, S1P, and LSF, mediate the signaling to eNOS (15). In their studies of aortic ring relaxation in response to HDL, SPC, S1P, and LSF, the relative contribution of the lysophospholipids to signal activation by HDL is uncertain because the concentrations provided by HDL were 20-fold lower than those for the individually tested lysophospholipids. The experiments with aortas from S1P3-knockout mice more clearly suggest that 50–60% of the response to HDL is mediated by lysophospholipids (15). However, as the process is SR-BI dependent and recent work on the SR-BI adaptor molecule PDZK1 indicates that the mechanisms determining SR-BI abundance may be complex (17), potential changes in SR-BI expression in S1P3 receptor–null mice should be evaluated. Interestingly, Kimura and coworkers recently observed that the migration and survival of cultured endothelial cells is also enhanced by lysophospholipids (18), but it has not yet been determined whether eNOS mediates these processes.

Previous work by Gong and coworkers suggests that another potential cargo of HDL, namely estradiol, plays a role in eNOS activation by the lipoprotein (19). They reported that HDL isolated from female humans or mice had greater capacity to stimulate the enzyme than did HDL from male humans or mice. These findings are quite exciting, but it should be noted that the experiments implicating a direct role of estradiol via estrogen receptor activation were limited. In addition, as pointed out by Nofer et al. (15), HDL-mediated responses were apparent at lipoprotein concentrations that would provide estradiol at levels as low as 5 × 10–16 M (19), which is six orders of magnitude below the concentrations shown to activate eNOS in prior reports (20, 21). Furthermore, human studies demonstrating that brief elevations in HDL enhance endothelial function have been performed mainly in males (see below), suggesting a lack of dependence on estradiol. Nofer and colleagues also compared responses to male and female HDL and found no difference. As is the case for the new information gained regarding lysophospholipids, the findings related to estradiol are of considerable potential importance, but interpretation and extrapolation at this point should be done with caution.

Relevant signaling events proximal to eNOS

Over the past decade it has been appreciated that multiple signal transduction pathways converge to regulate the activity of eNOS. Stimulation often occurs in association with elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and Ca2+-calmodulin binding, and tyrosine kinase-MAPK signaling is also frequently involved. In addition, protein kinases including Akt kinase, which is downstream of PI3K, enhance eNOS activity through serine phosphorylation at position 1,177 of human eNOS. In contrast, phosphorylation of Thr 497 yields attenuated eNOS activity (22). Regarding HDL regulation of eNOS, Mineo and colleagues determined that HDL causes an increase in phosphorylation at Ser 1,179 of bovine eNOS (equivalent to Ser 1,177 in human eNOS) and no change in Thr 497 phosphorylation. Further experiments indicated that HDL stimulation of eNOS also requires MAPK activation and that the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase src and PI3K reside upstream in the signaling pathway and cause parallel activation of Akt and MAPK and their resultant independent modulation of the enzyme (23).

The current report by Nofer and coworkers provides additional insights into HDL signaling to eNOS (15). Along with data confirming HDL-induced phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS, they show that HDL causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+, and that Ca2+ is required for HDL-induced NO formation. In parallel, SPC, LSF, and S1P caused eNOS phosphorylation at Ser 1,177 and increases in intracellular Ca2+. However, the relative contribution of the lysophospholipids to HDL actions upstream of eNOS should be assessed with care because SPC, LSF, and S1P were tested at concentrations that were 30-fold greater than those present when the effects of native HDL were evaluated. In contrast to these findings and those of Mineo and coworkers (23), studies previously reported by Li et al. did not implicate a role for either PI3K–Akt kinase or calcium (13). Alternatively, they suggested that the HDL response occurs via the stimulation of ceramide production. However, in the latter work, studies were performed in Chinese hamster ovary cells and not in endothelial cells, and ceramide production with HDL and ceramide activation of eNOS were not causally linked (13). Although other potential mechanisms may be in play, the prevailing information indicates that HDL activation of eNOS entails the stimulation of multiple kinase cascades and calcium mobilization.

Evidence of HDL modulation of eNOS in humans

Whereas the functional link between HDL and eNOS has been appreciated only recently, the relationship between HDL and endothelium-dependent vasodilation has been known for some time. In studies of coronary vasomotor responses to acetylcholine, it was noted in 1994 that patients with elevated HDL have greater vasodilator and attenuated vasoconstrictor responses (24). Studies of flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery have also shown that HDL cholesterol is an independent predictor of endothelial function (25). The direct, short-term impact of HDL on endothelial function also has recently been investigated in humans. One particularly elegant study recently evaluated forearm blood flow responses in individuals who are heterozygous for a loss-of-function mutation in the ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1) gene. Compared with controls, ABCA1 heterozygotes (six men and three women) had HDL levels that were decreased by 60%, their blood flow responses to endothelium-dependent vasodilators were blunted, and endothelium-independent responses were unaltered. After a 4-hour infusion of apoAI/phosphatidylcholine disks, their HDL level increased threefold and endothelium-dependent vasomotor responses were fully restored (26). It has also been observed that endothelial function is normalized in hypercholesterolemic men with normal HDL levels shortly following the administration of apoAI/phosphatidylcholine particles (27). Thus, evidence is now accumulating that HDL is a robust positive modulator of endothelial NO production in humans.

More than an eNOS agonist

In addition to the modulation of NO production by signaling events that rapidly dictate the level of enzymatic activity, important control of eNOS involves changes in the abundance of the enzyme. In a clinical trial by the Karas laboratory of niacin therapy in patients with low HDL levels (nine males and two females), flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery was improved in association with a rise in HDL of 33% over 3 months (28). They also demonstrated that eNOS expression in cultured human endothelial cells is increased by HDL exposure for 24 hours. They further showed that the increase in eNOS is related to an increase in the half-life of the protein, and that this is mediated by PI3K–Akt kinase and MAPK (29). Thus, the same mechanisms that underlie the acute activation of eNOS by HDL appear to be operative in upregulating the expression of the enzyme.

Another important feature of eNOS regulation involves the myristoylation and palmitoylation of the protein, resulting in trafficking to caveolae, which are a subclass of liquid-ordered, cholesterol-rich domains (lipid rafts). The eNOS protein resides within a signaling module in caveolae that contains all of the molecular machinery necessary for its regulation by multiple ligands (22). The impact of lipoproteins on the lipid environment in caveolae and on eNOS localization was assessed by the Smart laboratory. Oxidized LDL was found to cause 90% of eNOS to leave caveolae, and acetylcholine-induced activation was attenuated. Further studies showed that this was due to oxidized LDL–induced depletion of caveolae cholesterol mediated by CD36 (30). However, coincubation of cells with HDL prevented oxidized LDL–induced translocation of eNOS from caveolae and restored acetylcholine activation. Additional work showed that this process is mediated by SR-BI and that it is related to the maintenance of caveolae cholesterol content due to cholesteryl ester uptake from HDL (31). Thus, along with its capacity to serve as an agonist for eNOS and to upregulate its expression, HDL may preserve the lipid environment in caveolae in the face of oxidized LDL, thereby maintaining the signaling module required for effective endothelial NO production and the atheroprotection that NO affords.

Unanswered questions

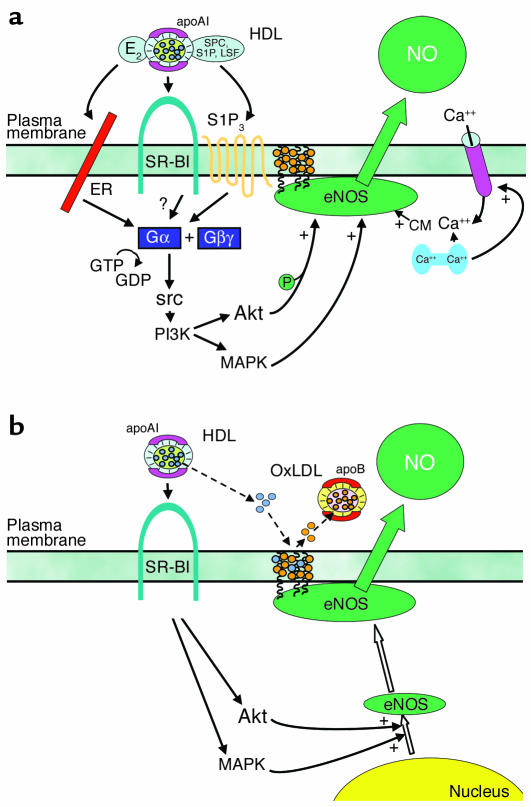

Our current understanding of the mechanisms by which HDL enhances endothelial NO production is summarized in Figure 1. The work by Nofer and colleagues on lysophospholipids (15) and the prior studies of HDL-coupled estradiol have provided valuable information about the potential components of HDL that mediate eNOS activity (19). However, perhaps related solely to the complexity of the lipoprotein, it is likely that additional characteristics are also important to inducing signaling in the endothelium. In particular, the role of the best described function of HDL in mediating cholesterol flux has yet to be determined. In addition, the impact of apolipoproteins besides apoAI should be considered. For example, a potential role for apoAII was revealed in studies in which eNOS activation by HDL in isolated endothelial plasma membranes was augmented by antibody to apoAII (12). The features of SR-BI requisite to eNOS activation are also unknown. The work related to lysophospholipids and estradiol suggests that SR-BI serves to tether HDL to the extracellular surface for the delivery of these ligands (15, 19). However, domains of SR-BI other than the extracellular loop may be necessary, as suggested by experiments in the endothelial cell plasma membrane paradigm in which antibody to the SR-BI cytoplasmic C-terminal tail prevented eNOS activation (12). In addition, the most proximal events occurring upon binding of HDL to SR-BI are unclear at present, and they represent the potentially most novel aspects of HDL action in endothelial cells. Perhaps most importantly, now that initial mechanistic insights have been gained in vitro, discrete manipulations of the HDL–SR-BI–eNOS pathway will be required in intact animal models to delineate if these processes mediate endothelial cell function in a physiological or pathophysiological context. With greater understanding in hand regarding both the underlying mechanisms and their implications, it will then be possible to consider therapeutic manipulation of direct HDL action on the endothelium to optimize cardiovascular health.

Figure 1.

HDL enhances NO production by eNOS in vascular endothelium. (a) HDL causes membrane-initiated signaling, which stimulates eNOS activity. The eNOS protein is localized in cholesterol-enriched (orange circles) plasma membrane caveolae as a result of the myristoylation and palmitoylation of the protein. Binding of HDL to SR-BI via apoAI causes rapid activation of the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase src, leading to PI3K activation and downstream activation of Akt kinase and MAPK. Akt enhances eNOS activity by phosphorylation, and independent MAPK-mediated processes are additionally required. HDL also causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration (intracellular Ca2+ store shown in blue; Ca2+ channel shown in pink), which enhances binding of calmodulin (CM) to eNOS. HDL-induced signaling is mediated at least partially by the HDL-associated lysophospholipids SPC, S1P, and LSF acting through the G protein–coupled lysophospholipid receptor S1P3. HDL-associated estradiol (E2) may also activate signaling by binding to plasma membrane–associated estrogen receptors (ERs), which are also G protein coupled. It remains to be determined if signaling events are also directly mediated by SR-BI (12, 15, 19, 22, 23). (b) HDL regulates eNOS abundance and subcellular distribution. In addition to modulating the acute response, the activation of the PI3K–Akt kinase pathway and MAPK by HDL upregulates eNOS expression (open arrows). HDL also regulates the lipid environment in caveolae (dashed arrows). Oxidized LDL (OxLDL) can serve as a cholesterol acceptor (orange circles), thereby disrupting caveolae and eNOS function. However, in the presence of OxLDL, HDL maintains the total cholesterol content of caveolae by the provision of cholesterol ester (blue circles), resulting in preservation of the eNOS signaling module (29–31).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Marilyn Dixon for preparing this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD30276, HL58888, and HL53546 (P.W. Shaul), the Crystal Charity Ball Center for Pediatric Critical Care Research, and the Lowe Foundation. C. Mineo is also supported by the Scientist Development Program of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 569.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABCA1); lysosulfatide (LSF); reverse cholesterol transport (RCT); scavenger receptor class B, member I (SR-BI); sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P); sphingosylphosphorylcholine (SPC).

References

- 1.Gordon DJ, Rifkind BM. High-density lipoprotein—the clinical implications of recent studies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989;321:1311–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foody JM, et al. HDL cholesterol level predicts survival in men after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: 20-year experience from The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Circulation. 2000;102:III90–III94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:737–741. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubins HB, et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:410–418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown BG, et al. Simvastatin and niacin, antioxidant vitamins, or the combination for the prevention of coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:1583–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden WE. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as an independent risk factor in cardiovascular disease: assessing the data from Framingham to the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000;86:19L–22L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger M. Charting the fate of the “good cholesterol”: identification and characterization of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:523–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger M. The “best” of cholesterols, the “worst” of cholesterols: a tale of two receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:4077–4080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jolley CD, Woollett LA, Turley SD, Dietschy JM. Centripetal cholesterol flux to the liver is dictated by events in the peripheral organs and not by the plasma high density lipoprotein or apolipoprotein A-I concentration. J. Lipid Res. 1998;39:2143–2149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brousseau ME, et al. Cellular cholesterol efflux in heterozygotes for tangier disease is markedly reduced and correlates with high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and particle size. J. Lipid Res. 2000;41:1125–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong S, et al. Increased coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased HDL levels. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2917–2923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuhanna IS, et al. High-density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor-BI activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nat. Med. 2001;7:853–857. doi: 10.1038/89986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XA, et al. High density lipoprotein binding to scavenger receptor, class B, type I activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in a ceramide-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11058–11063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen RA. The role of nitric oxide and other endothelium-derived vasoactive substances in vascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1995;38:105–128. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(05)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nofer J-R, et al. HDL induces NO-dependent vasorelaxation via the lysophospholipid receptor S1P3. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:569–581. doi:10.1172/JCI200418004. doi: 10.1172/JCI18004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rader DJ. Regulation of reverse cholesterol transport and clinical implications. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003;92:42J–49J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00615-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocher O, et al. Targeted disruption of the PDZK1 gene in mice causes tissue-specific depletion of the HDL receptor SR-BI and altered lipoprotein metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52820–52825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura T, et al. High-density lipoprotein stimulates endothelial cell migration and survival through sphingosine 1-phosphate and its receptors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:1283–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000079011.67194.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong M, et al. HDL-associated estradiol stimulates endothelial NO synthase and vasodilation in an SR-BI-dependent manner. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1579–1587. doi:10.1172/JCI200316777. doi: 10.1172/JCI16777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantin-Hermoso RL, et al. Estrogen acutely stimulates nitric oxide synthase activity in fetal pulmonary artery endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:L119–L126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.1.L119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caulin-Glaser T, Garcia-Cardena G, Sarrel P, Sessa WC, Bender JR. 17 beta-estradiol regulation of human endothelial cell basal nitric oxide release, independent of cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization. Circ. Res. 1997;81:885–892. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaul PW. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: location, location, location. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:749–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mineo C, Yuhanna IS, Quon MJ, Shaul PW. HDL-induced eNOS activation is mediated by Akt and MAP kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9142–9149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeiher AM, Schachlinger V, Hohnloser SH, Saurbier B, Just H. Coronary atherosclerotic wall thickening and vascular reactivity in humans. Elevated high-density lipoprotein levels ameliorate abnormal vasoconstriction in early atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1994;89:2525–2532. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li XP, et al. Protective effect of high density lipoprotein on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2000;73:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisoendial RJ, et al. Restoration of endothelial function by increasing high-density lipoprotein in subjects with isolated low high-density lipoprotein. Circulation. 2003;107:2944–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070934.69310.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spieker LE, et al. High-density lipoprotein restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic men. Circulation. 2002;105:1399–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013424.28206.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuvin JT, et al. A novel mechanism for the beneficial vascular effects of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: enhanced vasorelaxation and increased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. Am. Heart J. 2002;144:165–172. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramet ME, et al. High-density lipoprotein increases the abundance of eNOS protein in human vascular endothelial cells by increasing its half-life. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;41:2288–2297. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00481-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blair A, Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, Conrad PA, Smart EJ. Oxidized low density lipoprotein displaces endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) from plasmalemmal caveolae and impairs eNOS activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:32512–32519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uittenbogaard A, Shaul PW, Yuhanna IS, Blair A, Smart EJ. High density lipoprotein prevents oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced inhibition of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase localization and activation in caveolae. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11278–11283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]