Abstract

The proto-oncogene and inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), SET, interacts with the third intracellular loop of the M3 muscarinic receptor (M3-MR), and SET knockdown with small interfering RNA (siRNA) in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells augments M3-MR signaling. However, the mechanism of this action of SET on receptor signaling has not been defined, and we initiated studies to address this question. Knockdown of SET by siRNA in CHO cells stably expressing the M3-MR did not alter agonist-induced receptor phosphorylation or receptor internalization. Instead, it increased the extent of receptor dephosphorylation after agonist removal by ∼60%. In competition binding assays, SET knockdown increased high-affinity binding of agonist in intact cells and membrane preparations. Glutathione transferase pull-down assays and site-directed mutagenesis revealed a SET binding site adjacent to and perhaps overlapping the G protein-binding site within the third intracellular loop of the receptor. Mutation of this region in the M3-MR altered receptor coupling to G protein. These data indicate that SET decreases M3-MR dephosphorylation and regulates receptor engagement with G protein, both of which may contribute to the inhibitory action of SET on M3-MR signaling.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) define a large family of cell surface receptors that process signals from a great diversity of endogenous and exogenous stimuli. These receptors possess a characteristic seven-transmembrane domain architecture. Agonist binding to the receptor induces conformational changes within the GPCR that are propagated to intracellular domains, resulting in heterotrimeric G protein coupling to the receptor and activation of downstream signaling.

Signal transfer from the receptor to G proteins may be regulated by intracellular proteins that bind to cytoplasmic domains of the receptor and influence receptor trafficking, G protein activation, and/or the assembly of receptors into signal transduction complexes or “receptosomes” (Bockaert et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2006). Such signaling complexes may be stabilized by agonist or may be preformed and disrupted by agonist binding as part of the signal transfer process. The degree of stabilization or disruption of such signaling complexes by any given ligand is probably dependent on the conformation of the receptor stabilized by agonist, thus offering a platform for ligand-specific signaling events.

Most of the more than 80 GPCR interacting proteins identified to date interact with the carboxyl-terminal tail of GPCRs that contain interacting motifs such as the PDZ (PSD95-disc large-Zonula occludens), the Src homology 2 and 3, the pleckstrin homology, or the Ena/VASP homology domains (Bockaert et al., 2003). The third intracellular loop mediates G protein coupling and activation for most GPCRs. It is the largest intracellular portion of the receptor protein in many receptors and thus also participates in the assembly and processing of signaling complexes (Wu et al., 1997, 1998, 2000; Prezeau et al., 1999; Richman et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2004). We took advantage of recent technologies with enhanced sensitivity to detect specific interactions and identified SET protein (template activating factor I) as a binding partner of the third intracellular loop of the M3-MR (Simon et al., 2006). Functional analysis of the interaction demonstrated that SET has an inhibitory action on M3-MR signaling through Gq and that SET probably operates at the level of the M3-MR itself (Simon et al., 2006).

In the present article, we further characterized the regulation of M3-MR signaling by SET and addressed potential mechanisms that may account for this regulation. SET was first described as part of the SET-CAN fusion gene, a putative oncogene associated with acute undifferentiated leukemia (von Lindern et al., 1992). SE in SET refers to the patient with leukemia containing the SET translocation and the T in SET refers to translocation (von Lindern et al., 1992).

SET is widely expressed, whereas the M3-MR expression profile is more restricted. A review of mRNA expression profiles for SET and the M3-MR in human tissues indicates coexpression in several tissues including thymus, lung, prefrontal cortex, and liver (SET, http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=6418; http://bioinfo2.weizmann.ac.il/cgi-bin/genenote/GN_results.pl?keyword_type=2_gc_id&keyword=GC09P131445&data_type=norm2&results=yes; CHRM3, http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=1131; http://bioinfo2.weizmann.ac.il/cgi-bin/genenote/GN_results.pl?keyword_type=2_gc_id&data_type=norm2&results=yes&keyword=GC01P239549). A review of the Allen Brain Atlas indicates that SET and the M3-MR are both expressed in several specific brain tracts including the isocortex, olfactory areas, and hippocampal formation (SET, http://mouse.brain-map.org/gene/show/35371; CHRM3, http://mouse.brain-map.org/gene/show/12456).

Apart from its role in gene transcription regulation (Seo et al., 2001), SET is an inhibitor of the activity of PP2A (Li et al., 1996), a phosphatase involved in various signaling cascades (Lechward et al., 2001) and GPCR regulation (Pitcher et al., 1995; Krueger et al., 1997). PP2A is one of the major phosphatases involved in GPCR dephosphorylation (Pitcher et al., 1995). For many GPCRs, phosphorylation of the receptor by second messenger kinases and GRKs after agonist-mediated activation is an important aspect of receptor regulation (Budd et al., 2000). Phosphorylation of many GPCRs is associated with G protein uncoupling and receptor internalization, resulting in decreased responsiveness of the signaling system to agonist or perhaps receptor coupling to alternative signaling pathways through β-arrestin, which binds to the phosphorylated receptor (Lefkowitz and Shenoy, 2005; Kendall and Luttrell, 2009). Specific phosphorylation sites in the M3-MR are differentially regulated by different agonists and result in the regulation of distinct signaling pathways (Tobin et al., 2008; Butcher et al., 2011).

A phosphorylation-deficient M3-MR mutant elicits a more robust initial inositol phosphate response compared with that for the wild-type receptor (Budd et al., 2000). In addition, siRNA knockdown of endogenous SET in CHO cells stably expressing the M3-MR (CHO-M3 cells) augmented the increase in intracellular calcium in response to a short-term activation of the M3-MR (Simon et al., 2006). We thus hypothesized that SET regulates M3-MR signaling by influencing the phosphorylation status of the receptor and/or M3-MR-G protein coupling.

Materials and Methods

siRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing of SET.

CHO cells stably expressing the human M3-MR (CHO-M3 cells) plated in 100-mm dishes were transfected at 20 to 30% confluence with SET siRNA targeting different regions of human SET mRNA (GenBank accession no. D45198.1) using Lipofectamine 2000 as described previously (Simon et al., 2006). Three SET siRNA duplexes with 2- and 12-bp mismatch controls were used in various aspects of the study. Each SET siRNA duplex effectively reduced SET protein by 60 to 80%, whereas the control siRNA oligonucleotides did not alter the levels of SET protein. SET siRNA duplexes and their controls were as follows: 268cagaagaggucagaauugaucgcca292, 2-bp mismatch cagaagaggucGAaauugaucgcc, 12-bp mismatch agGGAGgACuUUaaCuAGGAAcca; 327ccauccacaagugucugcacugcuu351, 2-bp mismatch ccauccacaagGUucugcacugcuu, 12-bp mismatch ccaAcAcGUgAgucuUcacGCuCuu; and 530ccgaaaucaaauggaaaucuggaaa554, 2-bp mismatch ccgaaaucaaaGUgaaaucuggaaa. The siRNA duplexes 327–351 and 530–554 were generally used in combination (Simon et al., 2006). In siRNA control experiments for receptor phosphorylation and radioligand binding studies, cells were transfected with the corresponding predicted oligonucleotide control for the siRNA duplex (Simon et al., 2006). The transfection mixture was removed 5 h later and replaced by α-minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 250 μg/ml G418 (Geneticin; Invitrogen).

To assess SET knockdown, cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1% Nonidet P-40) and incubated for 1 h on ice. Cell homogenates were then centrifuged at 10,000g at 4°C, and 12 μg of the supernatant were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Expression of SET was assessed by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-SET antibody (1:1000) kindly provided by Dr. T. D. Copeland (National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD) (Adachi et al., 1994). Equal protein loaded was verified by reprobing blots with an anti-α-actin (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, Temecula, CA).

SET Expression.

CHO-M3 cells plated in 100-mm dishes were transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3::His-SET using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours later, cells were harvested for calcium measurements as described below. SET expression levels were assessed by performing electrophoresis of protein homogenates (12 μg) on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (10%), and membrane transfers were probed with anti-SET antibody.

M3 Muscarinic Receptor Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation.

CHO-M3 cells plated in 100-mm dishes were transfected with siRNA duplexes, and 48 h later, the cells (7 × 105 cells) were transferred to six-well plates in complete medium. The next day, confluent cells were washed three times in phosphate-free Krebs/HEPES buffer (10 mM HEPES, 118 mM NaCl, 4.3 mM KCl, 1.17 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 25.0 mM NaHCO3, and 11.7 mM glucose, pH 7.4) and incubated in phosphate-free Krebs/HEPES buffer supplemented with [32P]orthophosphate (50 μCi/ml) for 1 h at 37C. Cells were stimulated with the cholinergic agonist, carbachol (100 μM) for 5 min, and reactions were terminated by rapid aspiration of the drug-containing medium and application of 1 ml of ice-cold solubilization buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 500 nM microcystin, 50 mM NaF, 5 nM NaPPi, and 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, pH 7.4). Samples were left on ice for 20 min, passed through a needle syringe (26.5 gauge), and cleared by microcentrifugation. Cell lysates were precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads and then incubated on ice for 60 min with anti-M3-MR antibody raised against a GST-receptor fusion protein containing the third intracellular loop of the human M3-receptor (Ser345-Leu463) (Tobin et al., 1996). Immune complexes were isolated on protein A-Sepharose beads, and the beads were washed four times with solubilization buffer. Isolated immune complexes were then resolved on 8% SDS-PAGE gels. The gels were dried, and phosphorylated M3-MR was visualized and quantified using a Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager. The isolated immunes complexes were also visualized after electrotransfer by immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-M3MR antibody (provided by Dr. Jurgen Wess, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (Zeng and Wess, 1999).

For dephosphorylation experiments, [32P]orthophosphate-labeled cells were stimulated with carbachol (100 μM, 5 min), rapidly washed three times with phosphate-free Krebs/HEPES buffer, and incubated in this buffer for 5 or 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then lysed and processed as described above.

Receptor Internalization.

CHO-M3 cells plated in 100-mm dishes were transfected with siRNA duplexes, and 48 h later cells were transferred to 24-well plates in complete medium. The next day, cells were washed three times in phosphate-free Krebs/HEPES buffer, serum-starved for 1 h in phosphate-free Krebs/HEPES buffer and then stimulated with 1 mM carbachol for 2 h. Reactions were terminated by aspiration, and the cells were washed three times with ice-cold Krebs/HEPES buffer. Cells were incubated with a saturating concentration (6 nM) of the hydrophilic muscarinic antagonist [3H]N-methylscopolamine (NMS) for 4 h on ice. Cells were then washed 2 times in ice-cold Krebs' buffer and solubilized by the addition of 1 ml of ice-cold solubilization buffer. Nonspecific binding was determined with a 10 μM concentration of the antagonist atropine. Cells were scraped and transferred to vials containing 3.5 ml of Ecoscint A (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA) for analysis by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Under these experimental conditions, nonspecific [3H]NMS binding was <3% of the total binding. Specific binding was normalized by the number of cells.

Competition Binding Assays.

For intact cell radioligand binding assays, CHO-M3 cells plated in 100-mm dishes were transfected with SET siRNA duplexes and 72 h later, cells were serum-starved for 2 to 3 h. Cells were detached from plates with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mM EDTA and centrifuged at low speed. The cell pellets were washed two times and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (4 × 106 cells/ml). Competition binding studies were conducted under predetermined equilibrium conditions. Assays were conducted in disposable borosilicate glass (VWR International, West Chester, PA) and initiated by the addition of 105 cells (25 μl) to 75 μl of binding buffer containing 0.5 nM [3H]NMS in the presence or the absence of increasing concentrations of carbachol (10−6–10−2 M) or atropine (10−10–10−5 M). The assay was incubated with shaking for 2 h at room temperature.

For membrane radioligand binding assays, CHO-M3 cells were transfected with SET siRNA duplexes as described above. After 72 h, cells were detached from plates with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mM EDTA, pelleted (200g, 5 min), and lysed in 0.5 ml per six-well dish of hypotonic lysis buffer [5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, and 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, with protease inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet, 1 tablet/10 ml; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN)] using a 26.5-gauge syringe. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 15,000g for 10 min to obtain crude membrane and cytosol fractions. Membranes were resuspended in 0.5 ml of membrane buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA with protease inhibitor). For binding assays, 25-μl membrane (50 μg of protein) samples were added to 75 μl of binding buffer containing 0.5 nM [3H]NMS in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of carbachol (10−6–10−2 M) or atropine (10−10–10−5 M) or GppNHp (10 μM).

For radioligand binding assays involving transient expression of receptor and receptor mutants, cells were transfected using polyethylenimine as a transfection reagent (Oner et al., 2010). Membrane and intact cell binding assays were terminated by addition of 4 ml of ice-cold binding buffer followed by filtration over GF/B glass-microfiber filters (Whatman, Clifton, NJ). Filters were washed 3 times with 4 ml of ice-cold binding buffer, transferred to vials containing 6 ml of Ecoscint A, and bound radioactivity was counted the next day by scintillation spectrometry. Competition binding data were analyzed by the nonlinear curve-fitting program Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Measurement of Cell Calcium Content.

To evaluate receptor-effector coupling, we determined the ability of agonist to increase intracellular calcium in CHO-M3 cells using a fluorometric imaging plate reader system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Seventy-two and 48 h after siRNA transfection and plasmid transfections, respectively, CHO-M3 cells were seeded in F12 medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (35 × 103 cells/100 μl/well) in 96-well clear-bottomed black microplates (Costar; Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA), precoated with 100 μg/ml poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Four hours later, cells were dye-loaded (Flipr Calcium 3 Assay Kit; Molecular Devices) with 100 μl of the dye-loading buffer containing 2.5 mM probenecid for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. During a data run, cells in different wells were exposed to different concentrations of drugs, and the system recorded fluorescent signals for all 96 wells simultaneously every 5 s for 5 min. Increases in intracellular calcium were observed as sharp peaks above the basal fluorescent levels, typically 10 s after drug addition. The increases in intracellular calcium levels were determined by subtracting the baseline to the peak values (heights). Data were plotted using Prism (version 4.0). Data are representative of three to five independent experiments, and the data point for any drug concentration is an average from three to four wells.

Protein Recombinant Preparation.

To generate the M3-MR third intracellular loop constructs (M3-i3) (Thr450-Gln490, Ile474-Gln490, Ile474-Ile483, and Met480-Gln490), complementary oligonucleotides from these regions were synthesized and annealed before ligation into the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites of the PGEX-4T-1 vector. All mutations were made using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). GST fusion proteins were expressed in BL21 cells and purified on glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK) as described previously (Wu et al., 1997, 2000). Immobilized fusion proteins were stored at 4°C, and each batch of fusion proteins used for experiments was first analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. The full-length encoding sequence of human SET cloned into the pQE30 vector was kindly provided by Dr R. Z. Qi (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, China). The His-tagged SET protein was expressed in M15 bacteria and purified on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

GST Pull-Down Assays.

Human recombinant His-tagged SET protein (30 nM) was gently mixed for 1 h at 4°C with the GST fusion proteins (300 nM) bound to the glutathione Sepharose 4B matrix (12.5 μl) in 750 ml of buffer A [25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630, and protease inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet, 1 tablet/10 ml)]. Resins were washed 3 times with 500 ml of buffer A. The retained proteins were eluted from the resin with 25 μl of 5× loading buffer, placed in a boiling water bath for 5 min, and applied to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Separated proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and processed for immunoblotting with the polyclonal anti-SET antibody. Membranes were systematically reprobed with an anti-GST antibody (1:5000; GE Healthcare) to control for equal amounts of GST fusion proteins and protein loading.

Results

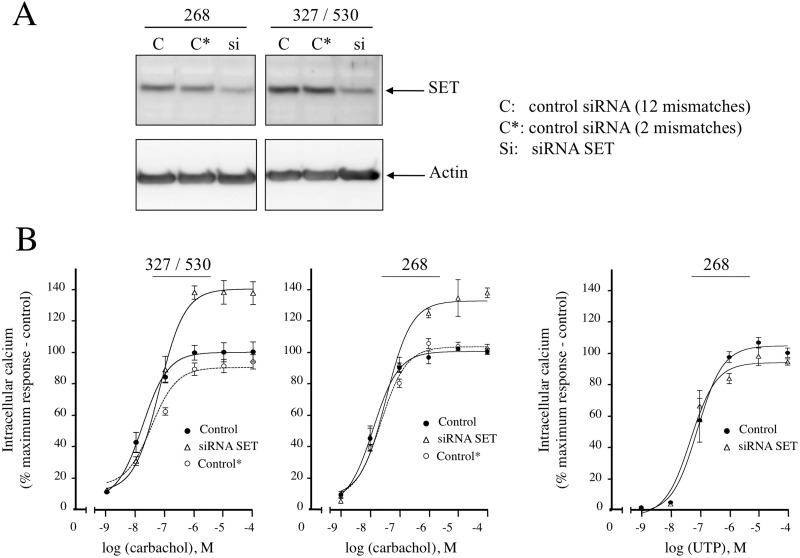

In our previous study reporting the interaction of SET with the M3-MR, SET knockdown augmented carbachol-induced increases in mobilization of intracellular calcium. To further validate these observations and to reduce the chances of any off-target effects of the siRNA, we extended these studies to include siRNA oligonucleotides targeting a different region of SET mRNA and also generated additional controls with 2-bp mismatches. SET siRNA 268–292 effectively reduced SET protein and had the same effect on M3-MR signaling as the SET siRNA 327–351 and 530–554 oligionucleotides used in our previous study (Fig. 1A) (Simon et al., 2006). Control siRNAs with 2- and 12-bp mismatches did not knock down SET protein and did not affect M3-MR-mediated regulation of calcium signaling (Fig. 1, A and B). P2 purinergic receptor-mediated regulation of calcium signaling in CHO-M3 cells was not altered by the new SET siRNA 268–292 (Fig. 1B, right panel) as reported previously for the SET siRNA oligonucleotides 327–351 and 530–554 (Simon et al., 2006). These data indicate that any effect of SET siRNA knockdown on M3-MR signaling is not likely to be due to unrelated, off-target effects of SET siRNA.

Fig. 1.

SET siRNA knockdown in CHO-M3 cells and effect of SET knockdown on calcium mobilization by the Gq-coupled M3 muscarinic and P2 purinergic receptors. A, 12 μg of protein homogenates from CHO-M3 cells transfected with SET siRNA oligonucleotides 268–291 or SET siRNA oligonucleotides 327–351 and 530–554 and their controls (C and C*, control siRNA with 12 or 2 mismatches from the siRNA SET, respectively) were electrophoresed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (10%) and probed with anti-SET or anti-actin antibodies. B, CHO-M3 cells transfected with SET siRNA (327/530 or 268) or the respective controls were plated in 96-well black plates precoated with poly-d-lysine and loaded with fluorescent dye. Cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations (10−9–10−4 M) of the muscarinic agonist carbachol (left panel) or the P2 purinergic agonist UTP (right panel), and intracellular calcium mobilization was measured. Excitation fluorescence was 485 nm, and emission was detected at 520 nm using a 515-nm emission cutoff filter; fluorescence emissions were measured with the FlexStation 3 (Molecular Devices). The increases in intracellular calcium were determined by subtracting the baseline to peak values (heights). Results are expressed as the percentage of the maximal response in control cells (control). The data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments in triplicate.

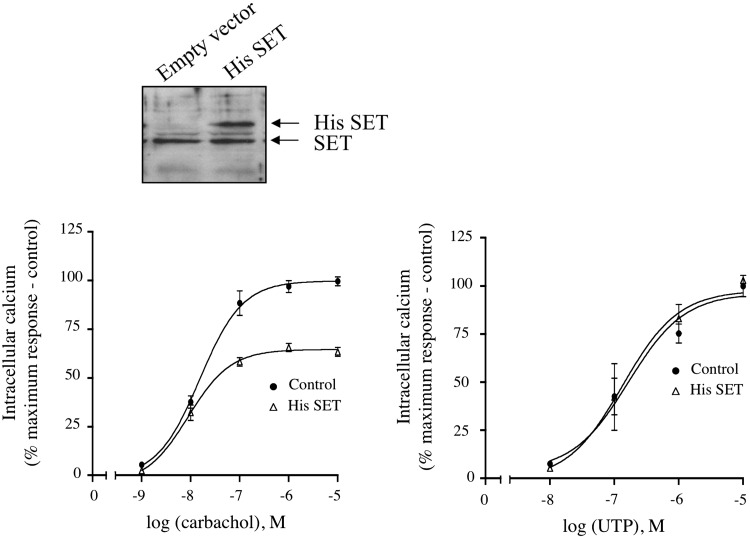

The SET knockdown studies were complemented with parallel studies to determine the effect of elevated SET expression on M3-MR signaling. An ∼2-fold increase in SET expression level in CHO-M3 cells reduced the efficacy of carbachol to mobilize intracellular calcium relative to control cells by ∼ 40% (Fig. 2, left panel). Of importance, SET overexpression did not alter the ability of the P2 purinergic receptor to mobilize intracellular calcium in CHO-M3 cells (Fig. 2, right). Collectively, these data indicate that SET exerts an inhibitory action on M3-MR calcium signaling.

Fig. 2.

Effect of increased SET protein on calcium mobilization by the Gq-coupled M3 muscarinic and P2 purinergic receptors in CHO-M3 cells. Top panel, 12 μg of protein homogenates from CHO-M3 cells transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3::His-SET were electrophoresed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (10%) and probed with anti-SET antibody. Bottom panel, transfected CHO-M3 cells were plated in 96-well black plates precoated with poly-d-lysine and loaded with fluorescent dye. Cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations (10−9–10−5 M) of the muscarinic agonist, carbachol (left panel) or the P2 purinergic agonist, UTP (right panel) and intracellular calcium mobilization was measured. Excitation fluorescence was 485 nm, and emission was detected at 520 nm using a 515 nm emission cutoff filter, and fluorescence emissions were measured with the FlexStation III (Molecular Devices). The increases in intracellular calcium were determined by subtracting the baseline to peak values (heights). Results were expressed as the percentage of the maximal response in cells transfected with pcDNA3 (control). The data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. of two to four independent experiments each performed in triplicate.

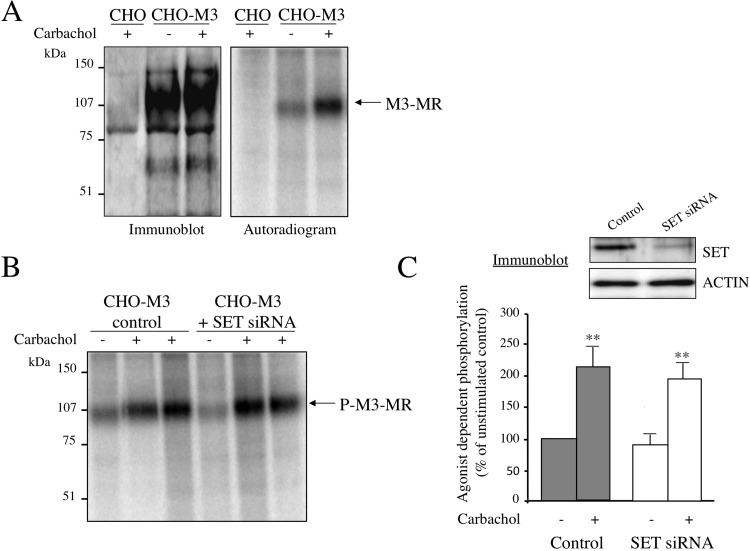

Influence of SET on M3 Muscarinic Receptor Phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of GPCR influences receptor signaling by altering receptor-G protein coupling. We first evaluated the effect of SET on basal and agonist-induced increases in M3-MR phosphorylation. CHO-M3-MR transfectants were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and stimulated with the agonist carbachol (100 μM, 5 min), and the incorporation of phosphates into the receptor was measured after immunoprecipitation of the M3-MR followed by separation by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (Fig. 3). Immunoblots indicated the immunoprecipitation of a specific receptor species from CHO-M3-MR transfectants that was absent in control CHO cells, and similar amounts of receptor were immunoprecipitated in the presence and absence of carbachol (Fig. 3A, left panel). The phosphorylated M3-MR appeared as a single band of ∼100 kDa that was absent in CHO cells lacking the M3-MR (Fig. 3A, right panel). Furthermore, stimulation of cells with the muscarinic agonist carbachol increased the intensity of this band (Fig. 3A, right panel). Indeed, carbachol induced an ∼2-fold increase in the level of M3-MR phosphorylation compared with basal receptor phosphorylation. To assess the role of SET in M3-MR phosphorylation events, we successfully decreased by ∼90% the endogenous SET expression levels by transfection of cells with SET siRNA (Fig. 3C). Comparison of the extent of agonist-induced M3-MR phosphorylation in control cells and in cells transfected with SET siRNA revealed that SET does not have any significant effect on basal or agonist-induced M3-MR phosphorylation (Fig. 3, B and C). Indeed, quantification of the radioactivity in the immunoprecipitated receptor was similar with or without reduction of endogenous SET expression (Fig. 3C, control: 2.1 ± 0.3-fold over basal; SET siRNA: 2.3 ± 0.3-fold over basal). These data suggest that SET is not dynamically involved in either basal phosphorylation of receptor or agonist-mediated increases in phosphorylation.

Fig. 3.

M3 muscarinic receptor phosphorylation. A, CHO or CHO-M3 cells were plated in six-well plates and labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (50 μCi/ml, see Materials and Methods). Cells were stimulated (+) or not (−) with the cholinergic agonist carbachol (100 μM) for 5 min. After agonist removal, cells were lysed and processed as indicated under Materials and Methods. Immunoprecipitated M3-MRs were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE, and the gel was either dried and subjected to autoradiography or electrotransferred and probed with a polyclonal anti-M3-MR antibody. Phosphorylated M3-MRs were visualized using a Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager. The autoradiogram shown is representative of four independent experiments. B, M3-MR phosphorylation was measured in CHO-M3 cells transfected with control siRNA or SET siRNA oligonucleotides 327–351 and 530–554 as described in A. The autoradiogram shown is representative of four independent experiments. C, quantitative analysis of the agonist-dependent receptor phosphorylation. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. of four independent experiments. Basal receptor phosphorylation values were not significantly different among control cells and cells transfected with SET siRNA (SET siRNA 90.4 ± 32.2% of control). Individual pairwise comparisons were performed using Student's t test. **, p < 0.01 compared with unstimulated. Top panel, visualization of SET knockdown efficiency by immunoblotting; 12 μg of protein homogenates from CHO-M3 cells transfected with control siRNA (control) or SET siRNA were electrophoresed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (10%) and probed with anti-SET or anti-actin antibodies.

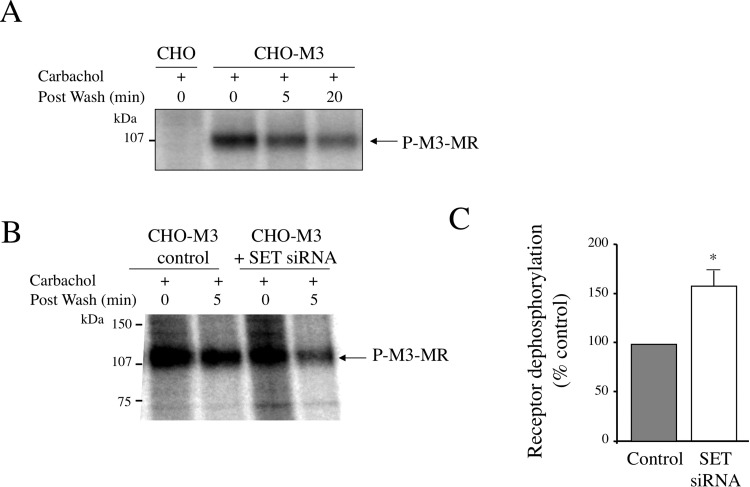

We then addressed the role of SET in M3-MR dephosphorylation (Fig. 4). After induction of receptor phosphorylation with carbachol (100 μM, 5 min), carbachol was removed, cells were incubated in agonist-free medium, and, at the end of the incubation, the remaining radioactivity in the receptor was measured. We determined that as soon as 5 min after agonist removal, receptor dephosphorylation is taking place and corresponds to an ∼25% decrease of the radioactivity of the immunoprecipitated M3-MR (Fig. 4A). At 20 min after agonist removal, the level of phosphorylated M3-MR is similar to basal levels observed in the absence of agonist. Of interest, in CHO-M3 cells in which endogenous SET expression was depleted by SET siRNA, early receptor dephosphorylation increases from ∼25 to ∼40% (percentage receptor dephosphorylation: control 23.6 ± 8.2%; SET siRNA 37.5 ± 12.2%) (Fig. 4, B and C). This corresponds to an ∼60% increase of receptor dephosphorylation in CHO-M3 cells lacking SET (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that SET inhibits M3-MR dephosphorylation after agonist removal and thus increases the period of time during which the receptor remains phosphorylated after agonist dissociates from the receptor.

Fig. 4.

M3 muscarinic receptor dephosphorylation. A, receptor dephosphorylation time course. Receptor phosphorylation (P) in CHO-M3 cells was induced by incubating cells with carbachol (100 μM, 5 min). At the end of the incubation, carbachol was removed by extensive washes, and receptor dephosphorylation was initiated (postwash: 5 or 20 min) or not (postwash: 0 min) by incubating cells in agonist-free medium for 5 or 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The autoradiogram shown is representative of two to three independent experiments. B, receptor dephosphorylation in CHO-M3 cells transfected with control siRNA or SET siRNA oligonucleotides 327–351 and 530–554 was measured as described in A. The autoradiogram shown is representative of three independent experiments. C, quantitative analysis of receptor dephosphorylation in control cells and cells transfected with SET siRNA. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. Individual pairwise comparisons were performed using Student's t test. *, p < 0.05 compared with control cells.

Effect of SET on M3 Muscarinic Receptor Internalization.

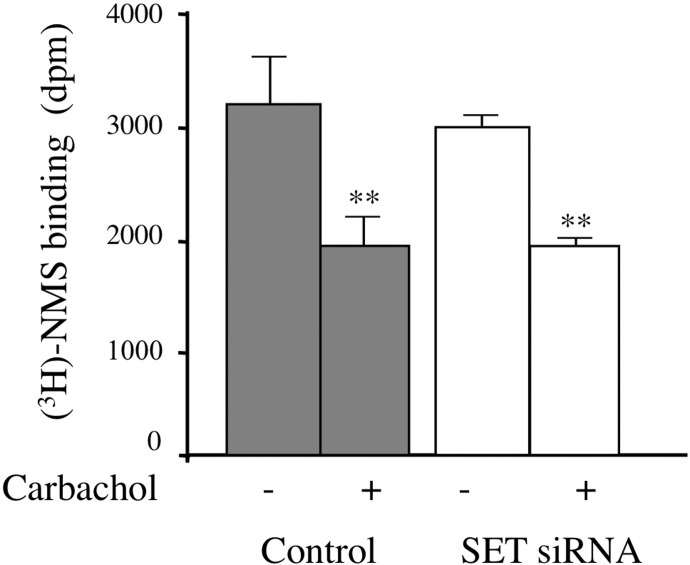

Because GPCR phosphorylation and dephosphorylation cycles are involved in GPCR functionality by regulating receptor trafficking from the plasma membrane to intracellular compartments, we asked whether SET could influence this process. We first asked whether SET siRNA influenced receptor expression levels by measuring cell surface receptors with the hydrophilic muscarinic antagonist [3H]NMS. SET siRNA treatment did not alter [3H]NMS binding to M3-MR (control 3078 ± 490 dpm; SET siRNA 2873 ± 194 dpm).

For receptor internalization studies, cells were incubated with carbachol for 2 h to induce maximal M3-MR internalization as described previously (Wu et al., 2000), leading to a 40.4 ± 5.6% decrease in [3H]NMS binding (Fig. 5). When cells were transfected with SET siRNA, the extent of receptor internalization did not differ from that in control cells (36.2 ± 3.4%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

M3 muscarinic receptor internalization. CHO-M3 cells transfected with control or SET siRNA oligonucleotides were stimulated (+) or not (−) with 1 mM carbachol for 2 h. After removal of the agonist, cells were incubated for 4 h on ice with a saturating concentration of the hydrophilic muscarinic antagonist [3H]NMS (6 nM). At the end of the incubation, unbound [3H]NMS was removed by extensive washes, cells were solubilized, and radioactivity was measured by scintillation spectrometry. The data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. of four independent experiments performed in triplicate. Results are indicated as specific radioligand binding for 105 cells. Individual pairwise comparisons were performed using Student's t test. **, p < 0.01, compared with receptor binding in absence of carbachol.

SET Alters Agonist Binding to Receptor and Receptor Signaling.

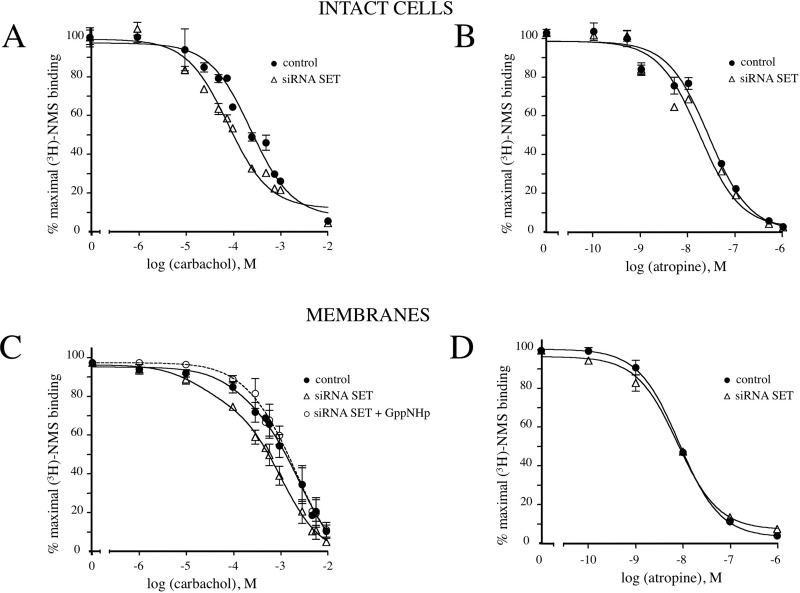

We next examined M3-MR interaction with G protein by determining the ability of the agonist carbachol to stabilize a high-affinity form of the receptor as detected by computer modeling of agonist competition curves for [3H]NMS binding. The high-affinity state of the receptor for agonist results from the formation of a ternary complex between the agonist, the receptor, and the G protein.

Competitive binding assays were first conducted in intact cells after treatment with control siRNA (control) or with SET siRNA. Increasing concentrations of the agonist carbachol displaced the antagonist [3H]NMS binding to M3-MRs (Fig. 6A). When endogenous SET expression was reduced by SET siRNA, agonist competition curves were shifted to the left compared with the control (SET siRNA IC50 0.09 ± 0.02 mM; control IC50 0.29 ± 0.07 mM) (Fig. 6A), reflecting an increase in agonist affinity. This shift to the left was quantitated as a 3.13 ± 0.08-fold decrease in the IC50 exhibited by carbachol. In contrast, SET siRNA knockdown did not have any effect on the displacement of [3H]NMS binding by the antagonist atropine compared with that in control cells (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results suggest that SET decreases agonist binding to the receptor and that this may lead to decreased coupling of the M3-MR and G protein.

Fig. 6.

Competition binding studies with muscarinic ligands. A and B, cells (105 cells) were incubated with 0.5 nM [3H]NMS in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of (A) carbachol (10−6–10−2 M) or (B) atropine (10−10–10−6 M). C and D, membrane proteins (35 μg) prepared from cells transfected with control siRNA or siRNA SET oligonucleotides 327–351 and 530–554 were incubated with 0.5 nM [3H]NMS in the presence or absence of GppNHp (10 μM), and [3H]NMS binding was measured after addition of increasing concentrations of (C) carbachol (10−6–10−2 M) or (D) atropine (10−10–10−6 M). Competition curves were plotted as the percentage of maximal [3H]NMS binding in the absence of carbachol or atropine. The results shown are representative of three to five independent experiments each performed in triplicate.

To further address this question, we conducted similar experiments using membrane fractions from lysed cells. In membrane preparations from control cells, carbachol exhibited an IC50 value of 1.3 ± 0.7 mM (Fig. 6C). After SET knockdown, the agonist competition curve was shifted to the left and best fit to a two-site model (Fig. 6C). The IC50 values for the high- and low-affinity states of the receptor were 0.02 ± 0.01 and 1.1 ± 0.07 mM, respectively. SET knockdown thus induced the appearance of a high-affinity state of the receptor for agonist with an IC50 ∼60 times higher than that observed in control cells (1.3 ± 0.7 mM) and the lower-affinity state of the receptor for agonist in SET siRNA-transfected cells (1.1 ± 0.07 mM). In contrast, competition binding studies with the antagonist atropine were not altered by SET knockdown (Fig. 6D). To confirm that the appearance of a high-affinity state receptor by SET siRNA treatment results from a better coupling of M3-MR to G protein, we evaluated the effect of the nonhydrolyzable guanine nucleotide GppNHp on agonist competition curves. GppNHp inhibits the formation of the high-affinity state of the receptor for agonist. Of interest, preincubation with GppNHp of membranes reversed the effect of SET siRNA and shifted the curve rightward, resulting in a curve that was best fit to a one-site model and was indistinguishable from the curve obtained with control cells (SET siRNA + GppNHp IC50 = 1.5 ± 0.7 mM).

On the basis of our experience, high-affinity agonist binding and the associated effects of GppNHp in competitive radioligand binding studies for systems coupled to Gq (e.g., M3-MR) may be quite subtle compared with those for systems involving coupling to Gαi/o. Nevertheless, these data are also consistent with the interpretation that SET knockdown results in facilitated interaction of the M3-MR with G-protein.

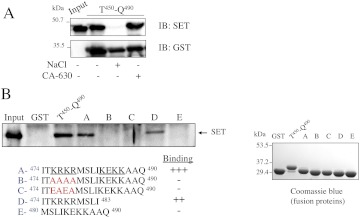

Localization of the SET Binding Site within M3 Muscarinic Receptor.

SET interaction with the M3-MR involves the carboxyl-terminal part of M3-i3 (amino acids 450–490, Thr450-Gln490) and more specifically the last 17 amino acids (Fig. 7A) (Simon et al., 2006). Of interest, among those 17 amino acids are key residues for Gq protein coupling and activation (Blin et al., 1995; Zeng et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2003). We thus addressed the role of specific regions in this 17-amino acid segment in the interaction with SET. SET interaction with the carboxyl-terminal end of M3-i3 was disrupted by incubation with high-salt buffer (0.5 M NaCl), whereas buffer containing detergent (1% IGEPAL CA-630) did not alter SET binding (Fig. 7A). These data indicate that charged rather than hydrophobic amino acids probably mediate SET binding to the M3-i3 segment. There are two clusters of positively charged amino acids within the last 17 amino acids of the i3 loop (Fig. 7B, fragment A, underlined amino acids KRKR and KEKK). To identify the amino acids required for SET binding, we generated mutants in which the first charged amino acid cluster was replaced by alanine or glutamic acid residues either neutralizing or reversing the positive charge (Fig. 7B, fragments B and C). Mutation of the first cluster KRKR into AAAA or EAEA abolished SET binding (Fig. 7B). This indicates that only the first cluster of charged amino acids is required for SET binding, and this is further confirmed by the fact that SET binds to a fragment containing only this cluster (Fig. 7B, fragment D) and not to a fragment containing only the second cluster (Fig. 7B, fragment E). SET thus binds to a site (amino acids 476–479) in close vicinity to amino acids involved in G protein coupling and activation (amino acids 484–490). This suggests that SET may compete with G protein for receptor binding and thus reduce M3-MR calcium signaling.

Fig. 7.

Localization of SET binding site within the M3-i3 loop. A, the carboxyl-terminal end of the third intracellular loop of the M3-MR (Thr450-Q490) was expressed in BL21 cells as a GST fusion protein and purified on glutathione Sepharose 4B. Purified GST fusion proteins were incubated with recombinant His-SET as described under Materials and Methods. Protein complexes were washed with buffer A (−) or buffer A containing 0.5 M NaCl or 1% IGEPAL CA-630 and bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE immunoblotting (IB) with SET and GST antibodies. The immunoblot shown is representative of three independent experiments. B, the carboxyl-terminal part or the last 17 amino acids of the M3-i3 loop (Thr450-Gln490 and fragment A, respectively) were expressed as a GST fusion protein in BL21 cells and purified on glutathione Sepharose 4B. Mutants and truncated fragments of the last 17 amino acids were also generated (fragments B–E). The red letters in sequences B and C indicate residues that were changed from wild-type sequence as described under Materials and Methods. Each purified construct was electrophoresed on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (10%) and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. Purified GST fusion proteins were incubated with recombinant His-SET and processed as described under Materials and Methods. The input represents the total amount of His-SET used for the interaction assay. The immunoblot shown is representative of three independent experiments.

We then asked whether disruption of the putative SET binding site (amino acids 476–479) in the context of the full-length receptor influenced receptor coupling in a manner similar to that observed after siRNA-mediated SET knockdown. We generated M3-MR constructs with mutations (476KRKR/AAAA M3-MR and 476KRKR/EAEA M3-MR) identical to those that disrupted SET binding in the M3i3 fragment Ile474-Gln490. Both constructs were expressed at levels comparable with those of the wild-type receptor as determined by whole-cell and membrane radioligand binding with [3H]scopolamine (S. S. Oner and S. M. Lanier, unpublished observations). However, both receptor mutants exhibited altered agonist affinity as determined by both competitive radioligand binding studies and calcium measurements. The receptor mutants both exhibited a reduction in the amount and/or affinity of the receptor population exhibiting high affinity for agonist, indicating that that these mutations influence receptor interaction with G protein (Supplemental Fig. 1). Agonist-induced increases in intracellular calcium were also examined after expression of wild-type receptor and the two mutant receptors in CHO cells. Both receptor mutants exhibited maximal responses to carbachol that were comparable with those of the wild type. However, the carbachol concentration-response curves were shifted to the right for the mutant receptors compared with wild-type receptor (Supplemental Fig. 1). Thus, the mutations apparently influence receptor interaction with G protein, complicating interpretation of the data in regard to SET engagement.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the role of SET in the regulation of M3-MR function. We first examined the impact of SET on the phosphorylation status of M3-MR. SET knockdown has no effect on M3-MR phosphorylation after receptor activation, but M3-MR dephosphorylation was accelerated by ∼60% after knockdown of SET. Considering the well established role of SET in the inhibition of the activity of PP2A, a phosphatase involved in GPCR dephosphorylation, one hypothesis is that the action of SET to inhibit receptor dephosphorylation is due to such an inhibitory action on PP2A. A growing number of GPCRs serve as substrates for PP2A. Among them, the chemokine receptor CXCR2 (Fan et al., 2001), the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (Mao et al., 2005), the β2-adrenergic receptor (Pullar et al., 2003), and more recently the G protein-coupled receptor GPR54 (Evans et al., 2008).

Although there is no direct functional evidence that PP2A dephosphorylates the M3-MR, per se, a recent study indicates the binding of both SET and PP2A to the third intracellular loop of selected muscarinic receptor subtypes (Borroto-Escuela et al., 2011). Although not reported for all subtypes, the interaction of SET with the M1 muscarinic receptor was dependent on agonist activation, whereas the interaction with PP2A was independent of agonist binding. Although the M3-MR and SET coimmunoprecipitated from CHO-M3-MR cell lysates (Simon et al., 2006), we could not detect any changes in the amount of SET in membrane preparations or at the cell cortex as determined by immunohistochemical analysis after agonist exposure (V. Simon and S. M. Lanier, unpublished observations). The amount of SET coimmunoprecipitating with the M3-MR from CHO-M3-MR cell lysates was also not apparently altered by agonist exposure (Supplemental Fig. 2). Initial studies to coimmunoprecipitate the M3-MR and SET from mouse brain tissue have been challenging because of the relatively low expression of the M3-MR (A. Butcher and A. B. Tobin, unpublished observations).

GPCR dephosphorylation is traditionally thought to occur in the late endosomal compartment after agonist-induced internalization of plasma membrane receptors to regenerate a functional receptor. Internalization of plasma membrane M3-MRs in intracellular compartments is initiated in CHO-M3 cells 30 min after incubation with the agonist carbachol (V. Simon and S. M. Lanier, unpublished observations) (Wu et al., 2000). In our experiments, M3-MR dephosphorylation seems to occur at a faster rate than that observed for receptor internalization. The different time courses of M3-MR internalization and dephosphorylation in CHO-M3 cells suggest that receptor dephosphorylation events are taking place at the plasma membrane rather than after receptor internalization. Several studies demonstrated that other GPCRs such as the D1 dopamine receptor (Gardner et al., 2001), the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor (Jones and Hinkle, 2005), and the β2-adrenergic receptor (Tran et al., 2007) are dephosphorylated at the plasma membrane. Dephosphorylation of GPCRs at the plasma membrane rather than in endosomes may provide a more rapid way of regeneration of a functional receptor without the need to enter the internalization and recycling pathways. This would allow a cell that was exposed to a brief agonist stimulation to respond again rapidly.

Receptor phosphorylation initiates receptor internalization and desensitization. Surprisingly, the decreased phosphorylation level of M3-MR observed after depletion of endogenous SET did not result in any significant change in receptor internalization. Despite the fact that M3-MR internalization is a phosphorylation-dependent process, data suggest that M3-MR internalization depends on the nature of the kinase phosphorylating M3-MR (Torrecilla et al., 2007). Indeed, Torrecilla et al. (2007) demonstrated that inhibition of casein kinase 2-mediated M3-MR phosphorylation did not significantly affect M3-MR internalization, whereas it is well established that M3-MRs are internalized in a GRK-dependent manner (Tsuga et al., 1998). One could hypothesize that, in the absence of SET, receptor dephosphorylation occurs preferentially on sites specifically phosphorylated by casein kinase 2 and not by GRKs.

Because receptor phosphorylation has an impact on receptor-G protein coupling, we examined G protein coupling to M3-MR by pharmacological approaches. Our data obtained from both intact cells and membrane fractions demonstrate that SET reduces G protein coupling to M3-MR. One possible hypothesis is that phosphatase inhibition by SET increases the life span of the phosphorylated receptor after dissociation of agonist, increasing β-arrestin binding that promotes G protein uncoupling. However, SET knockdown had no effect on receptor internalization, a process initiated by β-arrestin binding to the receptor. SET could also inhibit dephosphorylation of other signaling components involved in M3-MR signaling such as the Gαq/11 protein itself. Indeed, phosphorylation of Gαq/11 on serine 154 decreased Gq/11 protein coupling to 5-HT2A receptors and induced receptor desensitization (Shi et al., 2007). This hypothesis remains to be explored.

Our interaction studies in GST pulldown assays suggest that SET could inhibit G protein coupling by directly competing with G protein binding to the receptor. Indeed, the SET binding site (476KRKR479) sits next to the Gq protein binding site (484KEKKAAQ490) within the i3 loop of M3-MR (Blin et al., 1995; Zeng et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2003). Given the size of these two proteins, it is possible that binding of one will affect binding of the other.

On the basis of the increased maximal response to carbachol for intracellular calcium measurements observed after reduction of SET protein by SET siRNA and the reduction in maximal response to carbachol observed with increased SET expression, one might predict that the elimination of putative docking sites for SET in the third intracellular loop would also increase the maximal response to carbachol. However, this was not the case (Supplemental Fig. 1) because the disruption of these putative docking sites in the context of the intact receptor compromised receptor engagement with G protein.

Overall, our work highlights the new functions for the accessory protein SET in the regulation of M3-MR. We report that SET decreases M3-MR dephosphorylation and regulates M3-MR engagement with G protein. These actions of SET on M3-MR coupling probably contribute to the inhibitory effect of SET on M3-MR calcium signaling. The functional characterization of SET as a component of a muscarinic receptor signaling complex and an inhibitor of M3-MR signaling not only provides expanded functionality for SET but also presents a totally unappreciated mechanism for regulation of GPCR signaling capacity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Terry D. Copeland (National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD), Dr. Robert Z. Qi (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, China), and Dr. J. Wess (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for their kind gifts of materials. We also thank Dr. Ignacio Torrecilla (University of Leicester) for the helpful support in the phosphorylation experiments and Dr. Adrian Butcher (University of Leicester) for initial experiments involving immunoprecipitation of endogenous M3-MR. We dedicate this work to the beloved memory of Maureen Fallon.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [Grant 047600]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health [Grant MH90531]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant NS24821]; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale; and University Paris 7. S.M.L. was supported by the David R. Bethune/Lederle Laboratories Professorship in Pharmacology and a Research Scholar Award from Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Company (now Astellas Pharma).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- M3-MR

- M3 muscarinic receptor(s)

- PP2A

- protein phosphatase 2A

- GRK

- G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- bp

- base pair

- GST

- glutathione transferase

- PAGE

- polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- NMS

- N-methylscopolamine

- GppNHp

- 5′-guanylylimidodiphosphate

- M3-i3

- third intracellular loop of M3-MR

- i3 loop

- third intracellular loop.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Simon, Oner, Tobin, and Lanier.

Conducted experiments: Simon and Oner.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Cohen-Tannoudji and Tobin.

Performed data analysis: Simon, Oner, and Lanier.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Simon, Oner, Cohen-Tannoudji, Tobin, and Lanier.

References

- Adachi Y, Pavlakis GN, Copeland TD. (1994) Identification and characterization of SET, a nuclear phosphoprotein encoded by the translocation break point in acute undifferentiated leukemia. J Biol Chem 269:2258–2262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin N, Yun J, Wess J. (1995) Mapping of single amino acid residues required for selective activation of Gq/11 by the m3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem 270:17741–17748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J, Fagni L, Dumuis A, Marin P. (2004) GPCR interacting proteins (GIP). Pharmacol Ther 103:203–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J, Marin P, Dumuis A, Fagni L. (2003) The ‘magic tail’ of G protein-coupled receptors: an anchorage for functional protein networks. FEBS Lett 546:65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroto-Escuela DO, Correia PA, Romero-Fernandez W, Narvaez M, Fuxe K, Ciruela F, Garriga P. (2011) Muscarinic receptor family interacting proteins: role in receptor function. J Neurosci Methods 195:161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd DC, McDonald JE, Tobin AB. (2000) Phosphorylation and regulation of a Gq/11-coupled receptor by casein kinase 1α. J Biol Chem 275:19667–19675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher AJ, Prihandoko R, Kong KC, McWilliams P, Edwards JM, Bottrill A, Mistry S, Tobin AB. (2011) Differential G-protein-coupled receptor phosphorylation provides evidence for a signaling bar code. J Biol Chem 286:11506–11518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BJ, Wang Z, Mobley L, Khosravi D, Fujii N, Navenot JM, Peiper SC. (2008) Physical association of GPR54 C-terminal with protein phosphatase 2A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377:1067–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan GH, Yang W, Sai J, Richmond A. (2001) Phosphorylation-independent association of CXCR2 with the protein phosphatase 2A core enzyme. J Biol Chem 276:16960–16968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Liu ZF, Jiang D, Sibley DR. (2001) The role of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in agonist-induced desensitization of D1 dopamine receptor function: evidence for a novel pathway for receptor dephosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol 59:310–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BW, Hinkle PM. (2005) β-Arrestin mediates desensitization and internalization but does not affect dephosphorylation of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor. J Biol Chem 280:38346–38354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall RT, Luttrell LM. (2009) Diversity in arrestin function. Cell Mol Life Sci 66:2953–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger KM, Daaka Y, Pitcher JA, Lefkowitz RJ. (1997) The role of sequestration in G protein-coupled receptor resensitization. Regulation of β2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation by vesicular acidification. J Biol Chem 272:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechward K, Awotunde OS, Swiatek W, Muszyńska G. (2001) Protein phosphatase 2A: variety of forms and diversity of functions. Acta Biochim Pol 48:921–933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. (2005) Transduction of receptor signals by β-arrestins. Science 308:512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Makkinje A, Damuni Z. (1996) The myeloid leukemia-associated protein SET is a potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem 271:11059–11062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Yang L, Arora A, Choe ES, Zhang G, Liu Z, Fibuch EE, Wang JQ. (2005) Role of protein phosphatase 2A in mGluR5-regulated MEK/ERK phosphorylation in neurons. J Biol Chem 280:12602–12610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner SS, An N, Vural A, Breton B, Bouvier M, Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2010) Regulation of the AGS3-Gαi signaling complex by a seven-transmembrane span receptor. J Biol Chem 285:33949–33958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher JA, Payne ES, Csortos C, DePaoli-Roach AA, Lefkowitz RJ. (1995) The G-protein-coupled receptor phosphatase: a protein phosphatase type 2A with a distinct subcellular distribution and substrate specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:8343–8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezeau L, Richman JG, Edwards SW, Limbird LE. (1999) The ζ isoform of 14-3-3 proteins interacts with the third intracellular loop of different α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes. J Biol Chem 274:13462–13469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullar CE, Chen J, Isseroff RR. (2003) PP2A activation by β2-adrenergic receptor agonists: novel regulatory mechanism of keratinocyte migration. J Biol Chem 278:22555–22562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman JG, Brady AE, Wang Q, Hensel JL, Colbran RJ, Limbird LE. (2001) Agonist-regulated Interaction between α2-adrenergic receptors and spinophilin. J Biol Chem 276:15003–15008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Blumer JB, Simon V, Lanier SM. (2006) Accessory proteins for G proteins: partners in signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 46:151–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, Li B, Bloodworth L, Erlenbach I, Zeng FY, Wess J. (2003) Random mutagenesis of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expressed in yeast. Identification of point mutations that “silence” a constitutively active mutant M3 receptor and greatly impair receptor/G protein coupling. J Biol Chem 278:30248–30260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SB, McNamara P, Heo S, Turner A, Lane WS, Chakravarti D. (2001) Regulation of histone acetylation and transcription by INHAT, a human cellular complex containing the set oncoprotein. Cell 104:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Damjanoska KJ, Singh RK, Carrasco GA, Garcia F, Grippo AJ, Landry M, Sullivan NR, Battaglia G, Muma NA. (2007) Agonist induced-phosphorylation of Gα11 protein reduces coupling to 5-HT2A receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323:248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon V, Guidry J, Gettys TW, Tobin AB, Lanier SM. (2006) The proto-oncogene SET interacts with muscarinic receptors and attenuates receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 281:40310–40320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin AB, Butcher AJ, Kong KC. (2008) Location, location, location…site-specific GPCR phosphorylation offers a mechanism for cell-type-specific signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29:413–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin AB, Keys B, Nahorski SR. (1996) Identification of a novel receptor kinase that phosphorylates a phospholipase C-linked muscarinic receptor. J Biol Chem 271:3907–3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrecilla I, Spragg EJ, Poulin B, McWilliams PJ, Mistry SC, Blaukat A, Tobin AB. (2007) Phosphorylation and regulation of a G protein-coupled receptor by protein kinase CK2. J Cell Biol 177:127–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TM, Friedman J, Baameur F, Knoll BJ, Moore RH, Clark RB. (2007) Characterization of β2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation: comparison with the rate of resensitization. Mol Pharmacol 71:47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuga H, Okuno E, Kameyama K, Haga T. (1998) Sequestration of human muscarinic acetylcholine receptor hm1-hm5 subtypes: effect of G protein-coupled receptor kinases GRK2, GRK4, GRK5 and GRK6. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 284:1218–1226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lindern M, van Baal S, Wiegant J, Raap A, Hagemeijer A, Grosveld G. (1992) Can, a putative oncogene associated with myeloid leukemogenesis, may be activated by fusion of its 3′ half to different genes: characterization of the set gene. Mol Cell Biol 12:3346–3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhao J, Brady AE, Feng J, Allen PB, Lefkowitz RJ, Greengard P, Limbird LE. (2004) Spinophilin blocks arrestin actions in vitro and in vivo at G protein-coupled receptors. Science 304:1940–1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Benovic JL, Hildebrandt JD, Lanier SM.(1998) Receptor docking sites for G-protein βγ subunits. Implications for signal regulation. J Biol Chem 273:7197–7200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Bogatkevich GS, Mukhin YV, Benovic JL, Hildebrandt JD, Lanier SM. (2000) Identification of Gβγ binding sites in the third intracellular loop of the M3-muscarinic receptor and their role in receptor regulation. J Biol Chem 275:9026–9034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Krupnick JG, Benovic JL, Lanier SM. (1997) Interaction of arrestins with intracellular domains of muscarinic and α2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem 272:17836–17842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng FY, Hopp A, Soldner A, Wess J. (1999) Use of a disulfide cross-linking strategy to study muscarinic receptor structure and mechanisms of activation. J Biol Chem 274:16629–16640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng FY, Wess J. (1999) Identification and molecular characterization of m3 muscarinic receptor dimers. J Biol Chem 274:19487–19497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.