Abstract

Using two different and complementary approaches (flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry) on two independent cohorts of ovarian cancer patients, we found that accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in tumors is associated with early relapse. This deleterious effect of tumor-associated pDC was evident when they are present in cancer epithelium but not in lymphoid aggregates.

Keywords: immune tolerance, ovarian cancer, plasmacytoid dendritic cell, prognosis, progression-free survival

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) are one of the two main subsets of DC in human blood. They play a major role in anti-viral and autoimmune responses through their unique capacity to produce massive amounts of IFNα in response to both viral and self nucleic acids, respectively, following TLR7 and TLR9 engagement.1 However, their role in antitumor immunity has not been clarified yet. Emerging evidence indicates that tumor infiltration by pDC may have clinical importance, as underlined by their identification in melanoma, head and neck, lung, ovarian and breast cancers.1

Ovarian cancer (OC) is the most frequent and aggressive gynecologic cancer. This is due, at least in part, to its diagnosis at advanced stages (III/IV) in the majority of patients with peritoneal carcinosis and malignant ascites. In a recent report,2 we investigated the clinical significance of the presence of pDC in tumor mass and malignant ascites by conducting a systematic comparison of tumor-associated (TA) and ascites pDC. We observed an accumulation of pDC in most of malignant ascites and their presence at high frequency (highest tertile) in 36% of tumors whereas they were profoundly depleted in blood. Importantly, only accumulation of pDC in tumors was an independent prognostic factor associated with early relapse while their presence in malignant ascites was not deleterious.

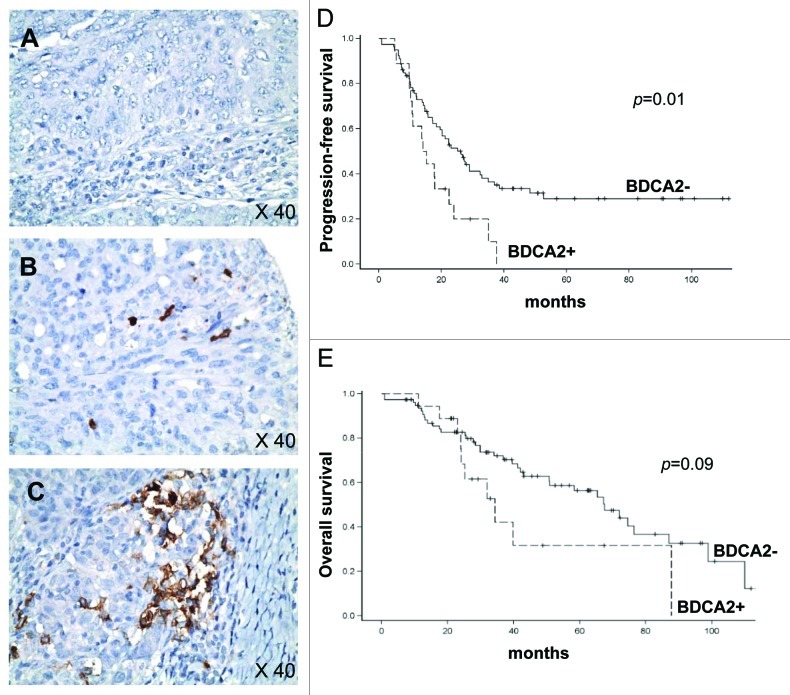

These initial results obtained on 33 patients in whom pDC were identified by flow-cytometry as CD4+BDCA2+CD123+ cells2 were confirmed on a larger series (n = 97 patients) treated for OC in Centre Leon Berard between 1997 and 2009 by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Thus, TApDC were identified as BDCA2+ cells (clone 104C12, Dendritics) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using tissue microarray allowing the analysis of impact of the presence of pDC in both cancer epithelium and lymphoid aggregates present in cancer stroma. BDCA2+ cells frequency was scored using a semi-quantitative method as 0 (no cells) (Fig. 1A), + (≤ 5 cells) (Fig. 1B) and ++ (> 5 cells) (Fig. 1C). BDCA2+ TApDC were present in only 18/97 tumors (18%) with a majority (73%) of score +. The median follow-up of the cohort was 34.1 mo. In univariate analysis, the presence of TApDC within cancer epithelium was associated with early relapse, as median progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated to 14.6 mo, compared with 26.2 mo in the absence of TApDC (p = 0.01, Fig. 1D). Similarly, median overall survival was shorter in the presence of TApDC, although not statistically significant (34.3 mo compared with 67.5 mo, p = 0.09; Fig. 1E). In multivariate analysis, in addition to clinical prognostic factors (advanced stage, debulking surgery and residual tumor), the presence of TApDC remains an independent prognostic factor associated with shorter PFS (HR = 2.19, 95%IC = 1.1–4.07, p = 0.02).

Figure 1. The presence of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) in ovarian cancer (OC) epithelium is associated with early relapse. (A–C) IHC analysis on paraffin-embedded ovarian tumor sections was performed using anti-BDCA2 (brown). Representative pictures of BDCA2+ pDC infiltration of OC epithelium scored as 0 (A), + (B) and ++ (C) are shown. Original magnification: x40. (D) Progression-free survival (PFS) according to the presence (+/++) or absence (0) of BDCA2+ pDC in OC epithelium (n = 97 OC patients). (E) Overall survival (OS) according to presence (+/++) or absence (0) of BDCA2+ pDC in OC epithelium (n = 97 OC patients). PFS and OS were calculated using Kaplan–Meier method.

Interestingly, the presence of TApDC into lymphoid aggregates had no impact on clinical outcome, suggesting a direct interaction between TApDC and tumor cells favoring tumor progression. Thus, using two different and complementary methods (flow-cytometry and IHC) on two independent cohorts, we observed a deleterious impact of the presence of TApDC within tumors on OC patient’s outcome. These data corroborate our findings in breast cancer3 and others in melanoma4 showing that TApDC accumulation correlates with poor prognosis. Collectively, these results suggest that TApDC may contribute to immune tolerance and tumor progression.

In our initial report in OC,2 we showed that, unlike ascites pDC, TApDC (1) expressed a semi-mature phenotype as evidenced by high levels of CD40 and CD86 and (2) were strongly affected for their IFNα production in response to CpG-A (TLR9 ligand) known to induce huge amounts of Type I IFNs. The alteration of IFNα production by pDC in response to TLR ligands has been previously described in chronic viral infections such as HIV and HCV contributing to the failure of an efficient immune response.5 In the context of cancer, previous works have also reported this alteration in breast,3 lung and head and neck cancers1 and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).6 Type I IFNs promote immunosurveillance through the activation of innate immune cells (reviewed in ref. 7) and inhibition of regulatory T cells.8 The critical role of type I IFNs in anti-tumor immunosurveillance is also well demonstrated in IFNα receptor 1-deficient mice where tumor growth is exacerbated.7 IFNα has also direct antitumor activities in OC in vitro and in vivo either in nude mice when associated to paclitaxel or in patients with minimal residual tumor9 by inhibiting OC cell proliferation, tumor growth and angiogenesis. Thus, the inhibition of IFNα production by TApDC in tumor microenvironment might confer a selective advantage for tumor cells allowing their progression.

In addition to altered immunosurveillance function, a direct contribution of pDC to tumor progression has been reported in multiple myeloma (MM) and ovarian cancer.1 Indeed, pDC in the bone marrow microenvironment promote MM cell growth, survival and drug resistance and pDC isolated from ovarian malignant ascites induce tumor angiogenesis in vivo in immunodeficient mice.1 In this context, it would be interesting to evaluate the impact of TApDC on tumor cell cycling and angiogenesis in situ in ovarian tumors.

Currently, we assist to a renaissance of IFN therapy for the treatment of myeloid malignancies. Preliminary results of a Phase III clinical trial in CML showed that a pegylated form of IFNα2a (pegIFNα2) in association with imatinib doubled molecular response (30%) in comparison to imatinib alone (14%, p = 0.001).10 By analogy to CML, the association of pegIFNα2a to chemotherapy could improve outcome in OC. Thus, restoring pDC capacity to produce Type I IFNs represents an attractive therapeutic strategy in cancer. In this context, the treatment of skin cancers with imiquimod (TLR7 ligand) resulted in IFNα production by TApDC that correlates to local immune reaction and destruction of tumor lesions.1

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- TApDC

tumor-associated pDC

- IFN

interferon

- OC

ovarian cancer

- TMA

tissue micro-array

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/18801

References

- 1.Vermi W, Soncini M, Melocchi L, Sozzani S, Facchetti F. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:681–90. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0411190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labidi-Galy SI, Sisirak V, Meeus P, Gobert M, Treilleux I, Bajard A, et al. Quantitative and functional alterations of plasmacytoid dendritic cells contribute to immune tolerance in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5423–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisirak V, Gobert M, Renaudineau S, Menetrier-Caux C, Aspord C, Banchereau J, et al. Breast tumor environment alters human plasmacytoid dendritic cells functions. In The 10th International Symposium on Dendritic Cells (Kobe, Japan) 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen TO, Schmidt H, Moller HJ, Donskov F, Hoyer M, Cjoegren P, et al. Intratumoral neutrophils and plasmacytoid dendritic cells indicate poor prognosis and are associated with pSTAT3 expression in AJCC stage I/II melanoma. Cancer. 2011;Epub ahead of press doi: 10.1002/cncr.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch I, Caux C, Hasan U. driss-Vermare N, Olive D. Impaired Toll-like receptor 7 and 9 signaling: from chronic viral infections to cancer. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohty M, Jourdan E, Mami NB, Vey N, Damaj G, Blaise D, et al. Imatinib and plasmacytoid dendritic cell function in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:4666–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–48. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golding A, Rosen A, Petri M, Akhter E, Andrade F. Interferon-alpha regulates the dynamic balance between human activated regulatory and effector T cells: implications for antiviral and autoimmune responses. Immunology. 2010;131:107–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berek JS, Markman M, Blessing JA, Kucera PR, Nelson BE, Anderson B, et al. Intraperitoneal alpha-interferon alternating with cisplatin in residual ovarian carcinoma: a phase II Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:48–52. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preudhomme C, Guilhot J, Nicolini FE, Guerci-Bresler A, Rigal-Huguet F, Maloisel F, et al. Imatinib plus peginterferon alfa-2a in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2511–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]