Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is characterized by expanded stroma with marked fibrosis. In Ijichi et al., we show that inhibiting CXCR2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival of a genetically-engineered mouse model recapitulating human pancreatic cancer. Targeting CXCLs/CXCR2 axis in the tumor microenvironment might be a potent therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: CTGF, CXC chemokine, CXCR2, pancreatic cancer, tumor microenvironment, tumor-stromal interaction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States and the fifth in Japan.1,2 It is one of the most lethal cancers, with five-year survival rate of less than 5%. Moreover, even with a successful resection, five-year survival is still less than 20%. The poor outcome after resection may be due to the frequent aggressive character of pancreatic tumor cells, which are often able to efficiently invade, disseminate and metastasize.3

We have established a genetically-engineered mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common type of human pancreatic cancer, using pancreas epithelium-specific knockout of TGFβ Type II receptor in the context of active Kras expression (Kras+Tgfbr2KO).4 This model recapitulated aggressive clinical characteristics and histological features of human PDAC, including abundant stromal components with marked fibrosis (desmoplasia) and median survival of 59 days.4

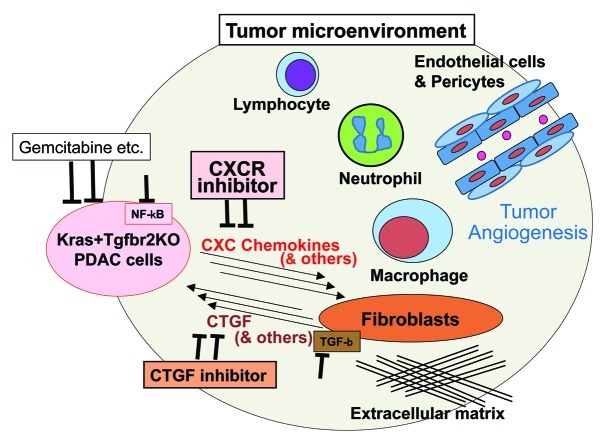

Recently, tumor microenvironment has been gaining increased attention. A number of components other than the tumor cells are involved in the tumor microenvironment: fibroblasts and a variety of extracellular connective tissues, macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes and other inflammatory and immune cells, vascular and lymphatic vessels etc. (Fig. 1). Interactions between the tumor and stromal cells and also between the stromal components might contribute to establish a condition in favor of the tumor cells.5,6,7 Understanding the underlying mechanisms might be especially important for the stroma-rich cancers, like pancreatic cancer.

Figure 1. Modulating tumor microenvironment in combination with conventional chemotherapy might be a promising therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer. Tumor microenvironment of the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) contains abundant stromal components other than the tumor cells (PDAC cells): fibroblasts and extracellular matrix, inflammatory and immune cells like macrophage, neutrophil, lymphocytes, and vasucular and lymphatic vessel systems including endothelial cells and pericytes etc. A wide variety of interactions of these components constitute an environment in favor of the PDAC cells, partly through tumor angiogenesis and an escape from the immune surveillance. The Kras+Tgfbr2KO PDAC cells secrete several CXC chemokines into the microenvironment and activate CXCR2 on the stromal fibroblasts. In response, the fibroblasts produce CTGF, which contributes to promote tumor angiogenesis. The CXC chemokine production from the PDAC cells is NFκB signaling-dependent and the CTGF expression from the fibroblasts is TGFβ signal-dependent. Therefore, to inhibit this tumor-stromal interaction, CXC chemokines and the receptor CXCR2, CTGF, NFκB signal in the PDAC cells and TGFβ signal in the fibroblasts can be therapeutic targets. The PDAC cells also secrete other important factors than the CXC chemokines, the fibroblasts also produce other factors than CTGF in response and other stromal components also respond to the stimuli from the PDAC cells, which remain to be further investigated. Since conventional chemotherapy like gemcitabine targets directly tumor cells, a combination of the inhibition of tumor-stromal interaction and the chemotherapy might provide a more effective therapeutic option.

In Ijichi et al.,8 we investigated the tumor-stromal interaction using our mouse model. We isolated the PDAC cells from the Kras+Tgfbr2KO pancreatic cancer tissue and mPanIN (mouse pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia) cells from the Kras alone-activated murine precancer tissue and screened secreted factors by using cytokine antibody array. This analysis revealed that CXC chemokines, CXCL1, 2, 5 and 16 were produced and secreted by the PDAC cells at a significantly higher level compared with the mPanIN cells. CXCL1, 2 and 5 bind the receptor CXCR2 and CXCL16 is a ligand of CXCR6. A CXCR2 inhibitor did not affect in vitro proliferation of the Kras+Tgfbr2KO PDAC cells, which indicated that the CXCR2 ligands did not promote the PDAC cell proliferation autonomously. We also observed that the CXCR2 ligands expression in the PDAC cells was NFκB signal-dependent.8

We isolated pancreatic fibroblasts, as a representative of stromal components in the pancreatic tumor tissue, from the Kras alone-activated mPanIN tissue. The genotyping PCR confirmed that the stromal fibroblasts did not contain Kras recombination. CXCR2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in the pancreatic fibroblasts than the PDAC cells and CXCR2 immunohistochemistry showed relatively prominent staining at the invasive front of the PDAC both in the stroma and epithelium.8 Taken together, the CXCR2 ligands secreted from the PDAC cells might influence on stromal fibroblasts and this tumor-stromal interaction could have a significant impact on PDAC progression.

Previously, we reported that connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a profibrotic and tumor-promoting factor, was strongly expressed at the tumor-stromal border of the Kras+Tgfbr2KO PDAC tissues,4 suggesting an active CTGF-dependent tumor-stromal interaction. We observed that the CTGF expression was significantly induced when the fibroblasts were incubated with the CXC chemokines or conditioned culture media from the PDAC cells and it was CXCLs/CXCR2 axis-dependent.8 TGFβ signaling, a well-known inducer of CTGF expression, was also required for the induction.

In the subcutaneous tumor grafting study in vivo, mixed cell tumors injected with a combination of the PDAC cells and pancreatic fibroblasts showed a faster growth compared with the tumors with the PDAC cells alone, which indicated a tumor-promoting tumor-stromal interaction. Growth of the mixed cell tumors showed a significant delay by treatment with CXCR2 inhibitor or when CXCR2 was knocked down in the fibroblasts.8 Therefore, the tumor growth might be highly dependent on the axis of CXCLs from the PDAC cells/CXCR2 on the stromal fibroblasts, thus the stromal CXCR2 can be a potent therapeutic target rather than epithelial CXCR2 in the tumor-stromal interaction.

When the Kras+Tgfbr2KO PDAC mice were treated with CXCR2 inhibitor with/without gemcitabine, the CXCR2 inhibitor decreased the tumor volume compared with the control group through inhibiting tumor angiogenesis and prolonged overall survival significantly.8 Decreased CTGF expression was also observed in the treated PDAC tissues. Gemcitabine, a standard chemotherapeutic agent of PDAC, also demonstrated a decrease of tumor volume and prolonged overall survival, however, it did not change the tumor angiogenesis, which meant a distinct mode of action. The CXCR2 treatment also demonstrated a decrease of macrophage and neutrophil infiltration in the PDAC tissue, suggesting a broad modification of the tumor microenvironment. In summary, in the Kras+Tgfbr2KO PDAC, that can recapitulate human PDAC, CXC chemokines are characteristically produced and secreted from the PDAC cells into the tumor microenvironment, which bind CXCR2 on the stromal fibroblasts and induce CTGF expression and tumor angiogenesis, resulting in PDAC progression (Fig. 1). When the CXCLs/CXCR2 axis is blocked, the tumor-promoting tumor-stromal interaction is abrogated, leading to decrease of the tumor volume and prolonged overall survival of the mice. This is a distinct mechanism of anti-cancer effect from that of conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Although we focused on the CXCLs/CXCR2 and CTGF using PDAC cells and fibroblasts in this study, there also seem other components and factors involved in the tumor-stromal interactions to be further investigated in the PDAC microenvironment. Pursuing the optimal combination of chemotherapeutic agents targeting directly PDAC cells and modulating agents of the tumor microenvironment might provide a promising therapy for PDAC (Fig. 1).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- mPanIN

mouse pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Tgfbr2

TGFβ Type II receptor

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/19402

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuno S, Egawa S, Fukuyama S, Motoi F, Sunamura M, Isaji S, et al. Pancreatic Cancer Registry in Japan: 20 years of experience. Pancreas. 2004;28:219–30. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre ME, Fujitani Y, Fujitani S, et al. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3147–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.1475506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes—bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ijichi H, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre ME, Bierie B, Tada M, et al. Inhibiting Cxcr2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4106–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI42754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]