Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) cells are characterized by high protein synthesis resulting in chronic endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which is adaptively managed by the unfolded protein response. Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α) is activated to splice X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, thereby increasing XBP1s protein, which in turn regulates genes responsible for protein folding and degradation during the unfolded protein response. In this study, we examined whether IRE1α-XBP1 pathway is a potential therapeutic target in MM using a small-molecule IRE1α endoribonuclease domain inhibitor MKC-3946. MKC-3946 triggered modest growth inhibition in MM cell lines, without toxicity in normal mononuclear cells. Importantly, it significantly enhanced cytotoxicity induced by bortezomib or 17-AAG, even in the presence of bone marrow stromal cells or exogenous IL-6. Both bortezomib and 17-AAG induced ER stress, evidenced by induction of XBP1s, which was blocked by MKC-3946. Apoptosis induced by these agents was enhanced by MKC-3946, associated with increased CHOP. Finally, MKC-3946 inhibited XBP1 splicing in a model of ER stress in vivo, associated with significant growth inhibition of MM cells. Taken together, our results demonstrate that blockade of XBP1 splicing by inhibition of IRE1α endoribonuclease domain is a potential therapeutic option in MM.

Introduction

Treatment for multiple myeloma (MM) has remarkably improved because of novel agents, such as bortezomib, thalidomide, and lenalidomide.1–3 However, MM remains incurable, and next-generation novel agents are urgently needed. Because of high levels of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and adaptation by the unfolded protein response (UPR), targeting signaling by the UPR and blocking this key survival pathway represent a new therapeutic strategy. In mammalian cells, protein folding is proportionally fine-tuned to the metabolic state of the cell within its microenvironment. Extracellular insults, such as low nutrients, hypoxia, and multiple drugs, result in the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER, thereby causing ER stress and initiating the UPR.4 The UPR in turn increases the biosynthetic capacity and decreases the biosynthetic burden of the ER, to maintain cellular homeostasis. However, when the stress cannot be compensated by the UPR, cellular apoptosis occurs.5 The UPR consists of 3 branches of signaling pathways, which initiate from 3 ER transmembrane proteins: inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). In the resting state, these proteins are associated with molecular chaperone BiP/GRP78 in the ER. However, when unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, BiP/GRP78 dissociates from them, thereby inducing UPR signaling.6

In the UPR, IRE1α is activated by oligomerization and autophosphorylation, resulting in activation of its endoribonuclease to cleave and initiate splicing of the X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA. A 26-nucleotide intron from XBP1 is removed by activated IRE1α endoribonuclease, resulting in a translational frame-shift to modify unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u: inactive) into spliced XBP1 (XBP1s: active).7 XBP1 is a unique transcription factor that regulates genes responsible for ER-associated degradation (ERAD), such as EDEM, and those responsible for promoting protein folding, such as p58IPK and other ER chaperones.8 Thus, IRE1α-XBP1 pathway has a prosurvival role in the UPR. However, under conditions of prolonged and uncompensated stress, the UPR leads to cellular apoptosis, known as the terminal UPR. The proapoptotic transcription factor CHOP, also known as GADD153, is induced via PERK and ATF6 pathways. CHOP causes down-regulation of BCL2, thereby leading to caspase-dependent apoptosis.9 IRE1α also has a proapoptotic role: it binds TRAF2 and activates ASK1, which causes JNK activation, thereby leading to caspase-dependent apoptosis.10

MM is a plasma cell malignancy characterized by excess monoclonal proteins. This burden of protein synthesis requires strict ER quality control; indeed, XBP1 is required for the generation of plasma cells.11 ER stress and the resulting UPR therefore represent a key target for MM therapy. For example, bortezomib, a selective inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, is known to induce the terminal UPR in MM cells.12 Specifically, bortezomib induces the accumulation of misfolded protein in the ER because inhibition of the proteasome disrupts the ERAD pathway. HSP90 inhibitors also activate the UPR,13 both by preventing HSP90 from folding proteins properly via GRP94 within the ER and by destabilizing IRE1α itself.14,15 XBP1 is one of the most promising targets of the UPR pathway in cancer therapy,16 especially in MM cells, because XBP1 is highly expressed in human MM cells17; and conversely, knockdown of XBP1 by siRNA sensitizes J558 mouse myeloma cells to stress-induced apoptosis.18 In murine models, XBP1s overexpression drives MM pathogenesis.19 XBP1 is essential for plasma cell differentiation and survival to maintain ER quality control, and MM cells similarly require XBP1 expression and splicing into active XBP1s to grow and survive. Previous reports suggest the clinical importance of XBP1 because increased expression of spliced XBP1 was associated with poor survival.20,21

In this study, we targeted IRE1α-XBP1 pathway in MM cells using a small-molecule inhibitor. We hypothesize that inhibition of XBP1 splicing will lead to inactivation of XBP1, directly resulting in death of MM cells and/or enhancing sensitivity of MM cells to other ER stress-inducing drugs bortezomib and HSP90 inhibitor. These studies provide the preclinical basis for protocols evaluating the clinical efficacy of targeting IRE1α-XBP1 pathway, alone and with bortezomib, to improve patient outcome in MM.

Methods

Reagents

MKC-3946 has an expanded hydrophobic core and a solubilizing group, which produced a more potent and soluble IRE1α inhibitor (manuscript in preparation) than the original hit compounds,22 and was provided by MannKind Corp. Plasma exposure levels of mice are shown in supplemental Figure 1. Bortezomib was obtained from Selleck Chemicals, 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG) from EMD Chemicals, tunicamycin (Tm) from Sigma-Aldrich, and recombinant human IL-6 from R&D Systems.

Human MM cell lines

Dex-sensitive MM.1S and resistant MM.1R human MM cell lines were kindly provided by Dr Steven Rosen (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). U266 and RPMI 8226 human MM cells were obtained from ATCC. Doxorubicin-resistant RPMI-DOX40 and melphalan-resistant RPMI-LR5 cells were kindly provided by Dr William Dalton (Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL). OPM1 and OPM2 plasma cell leukemia cell lines were kindly provided by Dr Edward Thompson (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX). IL-6–dependent INA6 cell line was provided by Dr Renate Burger (University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany). All cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 2μM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), with 2.5 ng/mL of IL-6 only in INA6 cells. For hypoxia treatment, cells were cultured in a hypoxic chamber with 0.1% O2 level.

Primary cells

Blood samples collected from healthy volunteers were processed by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) gradient to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Patient MM cells and bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were obtained from BM samples after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Mononuclear cells were separated using Ficoll-Paque density sedimentation, and plasma cells were purified (> 95% CD138+) by positive selection with anti-CD138 magnetic-activated cell separation microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Tumor cells were also purified from the BM of MM patients using the RosetteSep-negative selection system (StemCell Technologies). BMSCs were generated by culturing BM mononuclear cells for 4 to 6 weeks in DMEM medium complemented with 15% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Growth inhibition assay

The inhibitory effect of MKC-3946 on MM cell line growth was assessed by measuring 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrasodium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich) dye absorbance, as previously described.23

To measure proliferation of MM cells with or without BMSCs, the rate of DNA synthesis was measured by [3H]-thymidine (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) uptake, as previously described.24

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Invitrogen) and measured by a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Labtech). cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III First strand synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). To evaluate relative expression levels of XBP1u/XBP1s, RT-PCR analysis was performed using PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen). Human XBP1 primer sequences were as follows: 5′-CCTGGTTGCTGAAGAGGAGG-3′ and 5′-CCA TGGGGAGATGTTCTGGAG-3′. Murine XBP1 primer sequences were as follows: 5′-ACACGCTTGGGAATGGACAC-3′ and 5′-CCATGGGAAGATGTTCTGGG-3′. β-actin was used as a loading control, with primers as follows: 5′-GGGTCAGAAGGATTCCTATG-3′ and 5′-GGTCTCAAACATGATCTGGG-3. PCR products were analyzed on a 3.5% agarose gel. Gene expression was quantified using ImageJ 1.45s (National Institutes of Health).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences were as follows: Human XBP1, 5′-CCTGGTTGCTGAAGAGGAGG-3′ and 5′-CCA TGGGGAGATGTTCTGGAG-3′; ERdj4, 5′-GCTACTCCCCAGTCAATTTTCA-3′ and 5′-CCGATTTTGGCACACCTAAGAT-3′; P58IPK, 5′-TGTGTTTGGGATGCAGAACTAC-3′ and 5′-TCTTCAACTTTGACGCAGCTT-3′; SEC61A1, 5′-TGTCATCTCCCAAATGCTCTCA-3′ and 5′-ACAGGTAATAGCAAAGGCCAC-3′; CHOP, 5′-AGAACCAGGAAACGGAAACAGA-3′ and 5′-TCTCCTTCATGCGCTGCTTT-3′; and β-actin, 5′-GGATGCAGAAGGAGATCACTG-3′ and 5′-CGATCCACACGGAGTACTTG-3′. Thermal cycling conditions were 10 minutes at 95°C, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 1 minute at 60°C.

Western blotting

MM cells were treated with or without novel or conventional agents; cells were then harvested, washed, and lysed, as in prior studies.23,25 Nuclear extracts were prepared using Nuclear Extraction Kit (Panomics). Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and immunoblotted with antibodies: anti-IRE1α, BiP/GRP78, CHOP, PERK, eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α (Ser51), histone H3, PARP, caspase-3, TRAF2, SAPK/JNK, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), GAPDH, and α-tubulin (Cell Signaling); phopsho-IRE1α (Ser724; Thermo Scientific); XBP1, ATF4, and actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) Abs. Immunoprecipitation using anti-TRAF2 Abs was carried out as described previously.26

Detection of apoptosis by annexin V/propidium iodide staining

Detection of apoptotic cells was done with the annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) detection kit (Immunotech/Beckman Coulter), as previously described.27 Apoptotic cells were analyzed on a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva (BD Biosciences). Cells that were annexin V/FITC1 positive (with translocation of phosphatidylserine from the inner to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane) and PI negative (with intact cellular membrane) were considered as early apoptotic cells, whereas positivity for both annexin V/FITC1 and PI was associated with late apoptosis or necrosis.

Transient transfection of shRNA

XBP1 pLKO.1 shRNA vectors were obtained from the RNA Interference Screening Facility in the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Recombinant lentivirus was produced and transfection was performed, as previously described.28 A pLKO.1-based vector targeting luciferase was used as a control vector.

Murine xenograft models of human MM

CB17 SCID mice (48-54 days old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All animal studies were conducted according to protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 107 RPMI 8226 cells mixed with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) on day 0, and received treatment for 21 days starting on day1. Mice were assigned into 4 groups (n = 8): daily intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg/kg MKC-3946; intravenous injections of 0.15 mg/kg bortezomib twice a week; a combination of MKC-3946 intraperitoneally with bortezomib intravenously; and 10% HPBCD intraperitoneally with normal saline intravenously as a vehicle control. Tumor volume was calculated from caliper measurements every 3 to 4 days; mice were killed when tumors reached 1.5 cm in length. Survival was evaluated from the first day of treatment until death.

Human fetal bone grafts were implanted into CB17 SCID-mice (SCID-hu), as previously described.29,30 Briefly, 4 weeks after bone implantation, 2.5 × 106 INA6 cells were injected directly into the human BM cavity in the graft. Soluble human IL-6 receptor (shuIL-6R) from INA6 cells was used as an indicator of MM cell growth and burden of disease. It was measurable approximately 4 weeks after INA6 cell injection, and mice then received either 100 mg/kg drug or vehicle alone daily for 3 weeks. Blood samples were collected and assessed for shuIL-6R levels using an ELISA (R&D Systems).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student t test. The minimal level of significance was P < .05. Survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank analysis. The combined effect of MKC-3946 with bortezomib or 17-AAG was analyzed by isobologram analysis using the CompuSyn Version 1.0 software program (ComboSyn).

Results

IRE1α-XBP1 pathway plays a significant role in MM cell growth

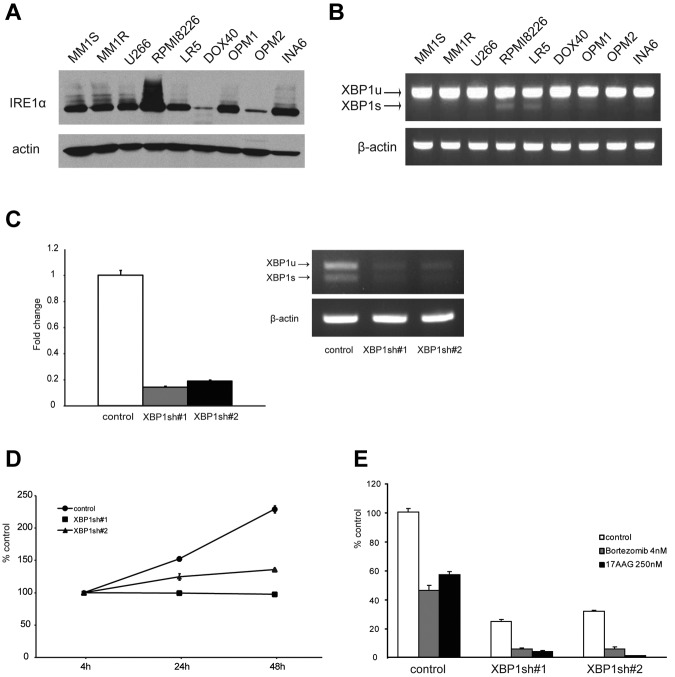

We first examined basal expression of IRE1α protein in MM cell lines (Figure 1A). Although there were differences in the level of expression, IRE1α was expressed in all cell lines. Next, RT-PCR was performed to examine the expression of XBP1 mRNA level in MM cell lines (Figure 1B). XBP1s was clearly detected in RPMI 8226 and LR5 cell lines.

Figure 1.

The significance of IRE1α-XBP1 pathway in MM cells. (A) Expression of IRE1α in MM cell lines was detected by Western blotting. Actin served as a loading control. (B) XBP1 mRNA was detected by RT-PCR. XBP1u was observed as a 152-bp band, and XBP1s was observed as a 126-bp band. β-actin served as a loading control. (C-E) RPMI 8226 cells were transduced with 2 independent shRNA lentivirus vectors (XBP1sh#1 and XBP1sh#2) to knockdown XBP1 gene expression. A vector-targeting luciferase was used as a control. (C) Three days after transduction, total RNA was extracted, and XBP1 mRNA was evaluated by real-time quantitative PCR in the graph. Data represent mean ± SD fold changes relative to β-actin mRNA in triplicate samples. Expression of XBP1u and XBP1s was examined by RT-PCR in the right panel. (D) Two days after transduction, cells were incubated for the indicated times. Growth of the cells was assessed by MTT assay of quadruplicate cultures, expressed as a percentage of 4-hour samples. Data represent mean ± SD. (E) Two days after transduction, cells were treated with bor-tezomib (4nM) or 17-AAG (250nM) for 48 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake of quadruplicate cultures, expressed as a percentage of untreated control vector cells. Data represent mean ± SD.

To investigate the significance of IRE1α-XBP1 pathway in MM cells, a targeted knockdown of XBP1 gene was performed using shRNA. Significant down-regulation of total XBP1 mRNA was observed in RPMI 8226 cells after transductions with 2 independent shRNAs (Figure 1C). We confirmed that both XBP1u and XBP1s were down-regulated. As a result of XBP1 knockdown, growth of MM cells was significantly inhibited (Figure 1D). Importantly, XBP1 knockdown sensitized cells to ER stressors, such as bortezomib or 17-AAG (Figure 1E). These results indicate that XBP1 has a crucial role in MM cell growth.

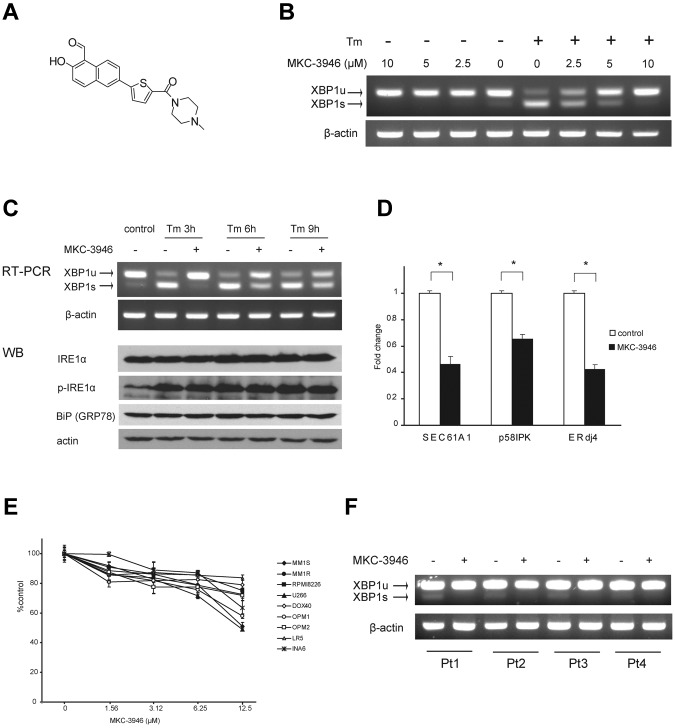

MKC-3946 is an IRE1α endoribonuclease domain inhibitor that blocks XBP1 mRNA splicing and triggers modest growth inhibition in MM cells

We next examined the impact of inhibition of XBP1 splicing using a small-molecule IRE1α endoribonuclease inhibitor MKC-3946 (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, we confirmed that MKC-3946 inhibited basal XBP1 splicing in RPMI 8226 cells.

Figure 2.

MKC-3946 is an IRE1α endoribonuclease inhibitor, which triggers modest cytotoxicity in MM cells. (A) Formal chemical structure of MKC-3946. (B) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with or without Tm (5 μg/mL) in combination with MKC-3946 (0-10μM) for 3 hours. Total RNA was extracted; XBP1 and β-actin mRNA were evaluated by RT-PCR. (C) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with Tm (5 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of MKC-3946 (10μM) for the indicated times. Total RNA was extracted, and XBP1 and β-actin mRNA were evaluated by RT-PCR. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using anti-IRE1α, phospho-IRE1α (p-IRE1α), BiP/GRP78, and actin Abs. (D) RPMI 8226 cells were cultured with or without MKC-3946 (10μM) for 8 hours. XBP1 target genes, such as SEC61A1, p58IPK, and ERdj4, were determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Data represent mean ± SD fold changes relative to β-actin mRNA in triplicate samples. *P < .001. (E) MM cell lines were cultured with MKC-3946 (0-12.5μM) for 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay of triplicate cultures, expressed as a percentage of untreated control. Data represent mean ± SD. (F) Primary MM cells isolated from patients (Pt) were cultured with or without MKC-3946 (10μM) for 6 hours. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR for analysis of XBP1 splicing.

Tm inhibits protein glycosylation in the ER and causes ER stress. After Tm treatment, increased expression of XBP1s mRNA and decreased expression of XBP1u were observed in RPMI 8226 cells. Importantly, MKC-3946 inhibited XBP1s expression induced by Tm in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). As shown in Figure 2C, IRE1α expression and phosphorylation were enhanced by Tm treatment, but MKC-3946 did not affect phosphorylation of IRE1α. We also examined downstream XBP1 target genes: SEC61A1, encoding the ER translocon component Sec61α31,32; p58IPK, a cochaperone in the ER33; as well as ERdj4, which stimulates ATPase activity of BiP and is essential for ERAD (Figure 2D).34,35 These genes were down-regulated by inhibition of XBP1 splicing with MKC-3946 treatment.

To assess the anti-MM effect of MKC-3946, MTT assay was performed using MM cell lines (Figure 2E). MKC-3946 induced modest cytotoxicity in MM cell lines. Importantly, normal mononuclear cells from healthy donors were not affected by MKC-3946 (supplemental Figure 2). MKC-3946 also inhibited XBP1 splicing in primary patient MM cells (Figure 2F).

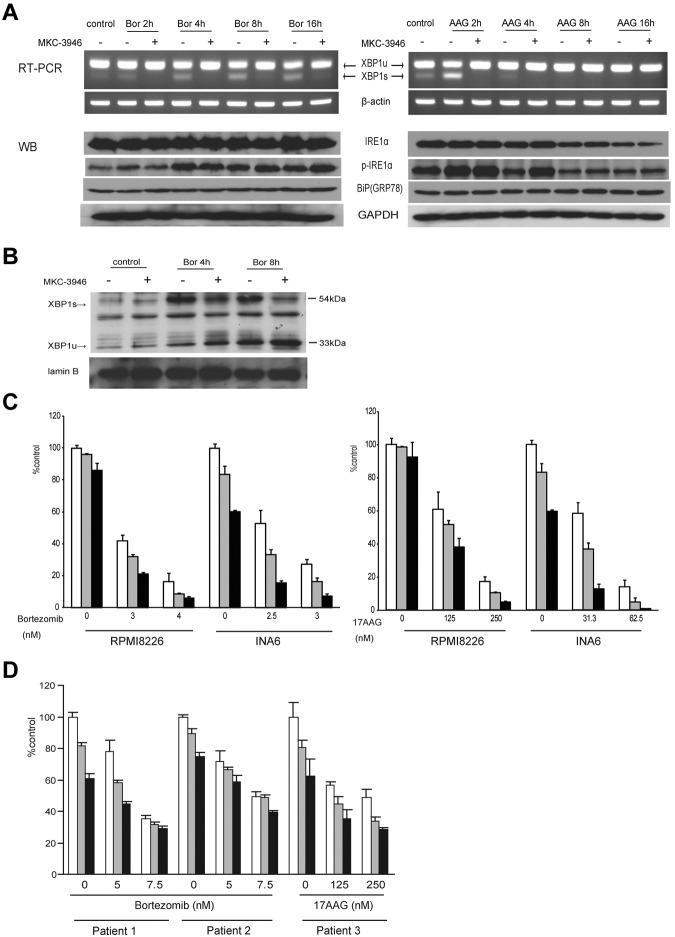

MKC-3946 blocks XBP1 splicing and enhances cytotoxicity induced by bortezomib or 17-AAG

Bortezomib is an effective proteasome inhibitor for MM therapy,36 which induces the terminal UPR, leading to apoptosis.12 HSP90 inhibitors, such as 17-AAG, are also reported to induce ER stress.13 The IRE1α-XBP1 pathway plays a protective role against ER stress because XBP1s acts as a transcription factor that promotes ER chaperone synthesis and ERAD. We therefore hypothesized that inhibition of XBP1 splicing in MM cells would enhance the terminal UPR induced by bortezomib and 17-AAG, thereby increasing sensitivity of the MM cells to these agents. In RPMI 8226 cells, XBP1 splicing was induced by either bortezomib or 17-AAG, correlating with ER stress; conversely, MKC-3946 blocked XBP1 splicing triggered by either of these agents (Figure 3A). The expression of IRE1α, phopsho-IRE1α, and molecular chaperone BiP/GRP78 was not inhibited by MKC-3946 treatment. As a result of 17-AAG treatment, down-regulation of IRE1α and its phosphorylation was observed because IRE1α is a client protein of HSP90.15 We also confirmed that XBP1s proteins were induced by bortezomib treatment, whereas down-regulation of XBP1s proteins and up-regulation of XBP1u proteins were triggered by MKC-3946 treatment (Figure 3B). In INA6 cells, MKC-3946 also inhibited XBP1 splicing induced by bortezomib (supplemental Figure 3, without BMSC).

Figure 3.

MKC-3946 blocks XBP1 splicing and enhances cytotoxicity induced by bortezomib or 17-AAG. (A) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with bortezomib (Bor; 10nM) or 17-AAG (AAG; 1μM), in the presence or absence of MKC-3946 (10μM) for the indicated times. Total RNA was extracted, and XBP1 and β-actin mRNA were evaluated by RT-PCR. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using anti-IRE1α, phospho-IRE1α (p-IRE1α), BiP /GRP78, and GAPDH Abs. (B) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with bortezomib (Bor; 10nM) in the presence or absence of MKC-3946 (10μM) for the indicated times. Nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blotting using XBP1 Abs. Lamin B served as a loading control. (C) RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib or 17-AAG in combination with MKC-3946, 0μM (□), 5μM (▩), or 10μM (■), for 48 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake of quadruplicate cultures, expressed as a percentage of untreated control. Data represent mean ± SD. (D) Primary MM cells isolated from 3 patients were treated with bortezomib or 17-AAG in combination with MKC-3946 0μM (□), 5μM (▩), or 10μM (■) for 36 hours. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay of triplicate cultures, expressed as a percentage of untreated control. Data represent mean ± SD.

The efficacy of MKC-3946 in combination with bortezomib or 17-AAG was next examined by [3H]-thymidine uptake. In RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells, MKC-3946 enhanced growth inhibition triggered by either bortezomib or 17-AAG (Figure 3C). Combination indices (CIs) showed additive cytotoxicity with bortezomib and synergism with 17-AAG (Table 1). Moreover, the anti-MM effect of bortezomib or 17-AAG was also significantly enhanced by MKC-3946 in primary MM cells from 3 patients (Figure 3D).

Table 1.

MKC-3946 combination indices (CI) with bortezomib or 17-AAG

| Bortezomib, nM | MKC-3946, μM | CI | 17-AAG, nM | MKC-3946, μM | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI 8226 | ||||||

| 3 | 5 | 1.04 | 125 | 5 | 1.06 | |

| 3 | 10 | 0.99 | 125 | 10 | 1.02 | |

| 4 | 5 | 0.91 | 250 | 5 | 0.89 | |

| 4 | 10 | 0.86 | 250 | 10 | 0.73 | |

| INA6 | ||||||

| 2.5 | 5 | 1.14 | 31.3 | 5 | 1.04 | |

| 2.5 | 10 | 1.04 | 31.3 | 10 | 0.75 | |

| 3 | 5 | 1.06 | 62.5 | 5 | 0.76 | |

| 3 | 10 | 0.96 | 62.5 | 10 | 0.44 |

RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib or 17-AAG and/or MKC-3946. Cytotoxicity was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake. CI was calculated using CompuSyn software. CI < 0.9 indicates synergistic effects, and CI > 0.9 indicates additive effects.

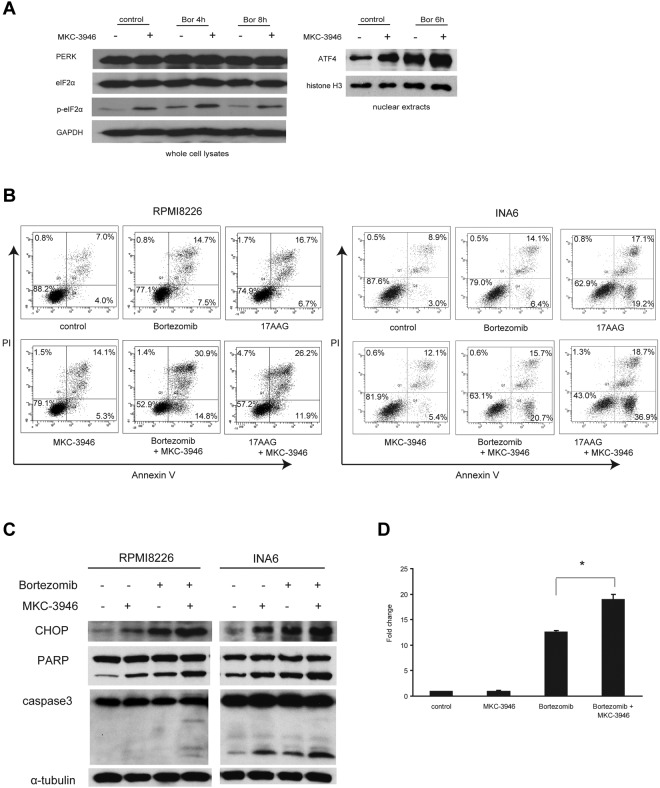

Inhibition of XBP1 splicing leads to activation of the PERK pathway and enhances the terminal UPR induced by ER stressors

We next examined PERK pathway, one branch of the UPR responsible for inhibition of new protein synthesis to decrease burden to the ER.4 Moreover, this is one of the pathways upstream of terminal UPR in uncompensated stress.5 After combined treatment with MKC-3946 and bortezomib, phosphorylation of eIF2α and expression of ATF4, mediated by activation of PERK pathway, were enhanced (Figure 4A), indicating that the PERK pathway was activated by inhibition of XBP1 splicing.

Figure 4.

MKC-3946 enhances ER stress-mediated apoptosis induced by bortezomib or 17-AAG. (A) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with bortezomib (Bor; 10nM) in the presence or absence of MKC-3946 (10μM) for the indicated times. Whole-cell lysates and nuclear extracts were subjected to Western blotting using PERK, eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α (p-eIF2α), and ATF4 Abs. GAPDH and histone H3 serve as loading controls. (B) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with bortezomib (2.5nM) or 17-AAG (500nM) and INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib (2.5nM) or 17-AAG (125nM), in each case in combination with MKC-3946 (10μM) for 24 hours. Apoptotic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using annexin V/PI staining. (C) RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib (2.5nM) in the presence or absence of MKC-3946 (10μM) for 24 hours. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using anti-CHOP, PARP, caspase-3, and α-tubulin Abs. (D) RPMI 8226 cells were treated with MKC-3946 (10μM), bortezomib (10nM), or the combination for 8 hours. CHOP mRNA was determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Data represent mean ± SD fold changes relative to β-actin mRNA in triplicate samples. *P < .001.

To elucidate the mechanism of enhanced cytotoxicity by MKC-3946 in combination with these ER stressors, we performed FACS analysis. Annexin V/PI staining showed that apoptosis induced in RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells by either bortezomib or 17-AAG was enhanced by MKC-3946 (Figure 4B). Western blotting showed that cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 was significantly enhanced by MKC-3946 in combination with bortezomib, associated with increased CHOP, a transcription factor leading to apoptosis by ER stress, in both RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells (Figure 4C). We further confirmed that CHOP mRNA transcription was significantly increased by MKC-3946 in combination with bortezomib (Figure 4D). MKC-3946 in combination with 17-AAG similarly enhanced CHOP induction followed by cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 in RPMI 8226 cells (supplemental Figure 4). In addition, binding of IRE1α to TRAF2, as well as phosphorylation of IRE1α and JNK, was enhanced by treatment of MKC-3946 alone or in combination with bortezomib (supplemental Figure 5). These data indicate that MKC-3946 treatment does not inhibit IRE1α kinase function or binding of activated IRE1α to TRAF2 and downstream JNK signaling.

These results suggest that inhibition of the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway results in increased ER stress, thereby triggering activation of the PERK compensatory pathway. Nonetheless, increased ER stress leads to the terminal UPR and apoptosis.

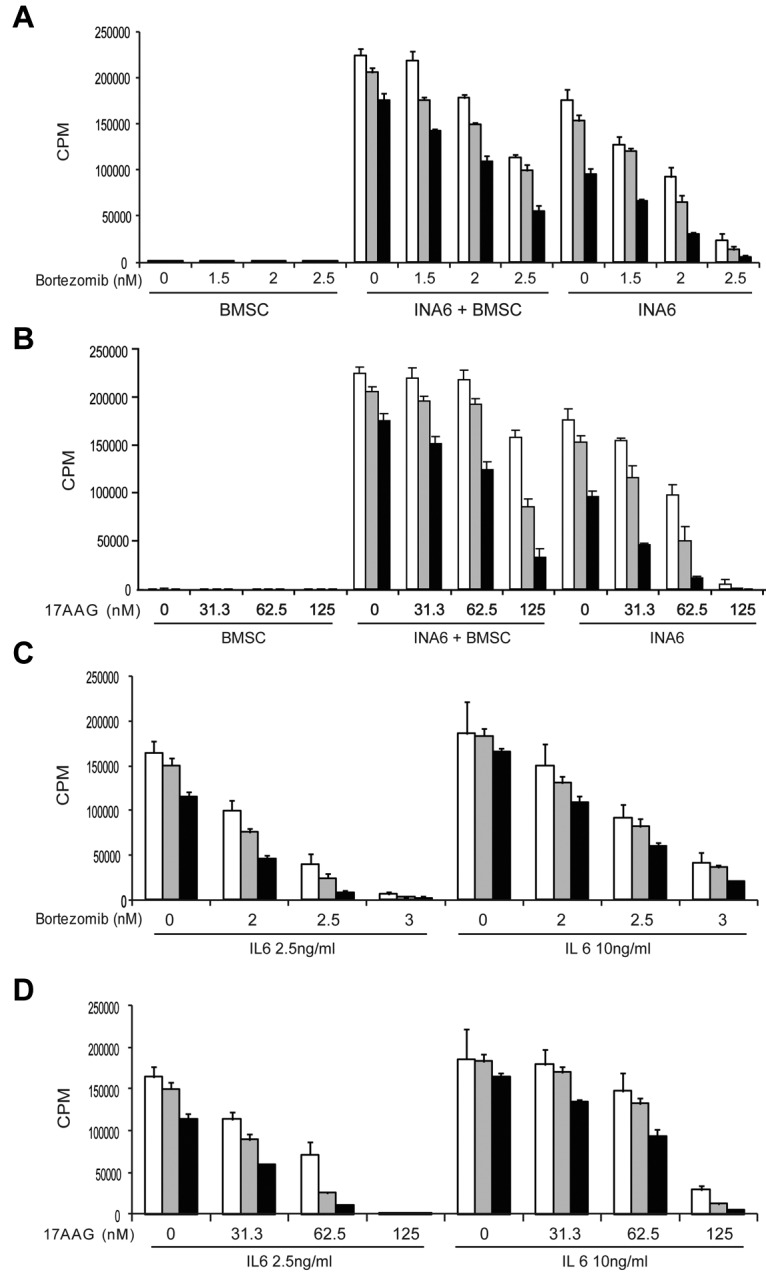

MKC-3946 enhances cytotoxicity of ER stressors, even in the presence of BMSCs or exogenous IL-6

Because cytokines, such as IL-6, secreted from BMSCs promote MM cell survival and protect against apoptosis, we next examined whether MKC-3946 in combination with bortezomib or 17-AAG can overcome this protective effect, using our models of MM cells in the BM microenvironment. As shown in supplemental Figure 3, XBP1s was induced by bortezomib in INA6 cells cocultured with BMSCs, and MKC-3946 inhibited this splicing. Importantly, MKC-3946 enhanced the cytotoxicity of bortezomib or 17-AAG in INA6 cells, even in the presence of BMSCs (Figure 5A-B) or exogenous IL-6 (Figure 5C-D), analyzed by [3H]-thymidine uptake. These results indicate that MKC-3946 in combination with ER stressors can overcome the tumor cytoprotective effects conferred by the BM microenvironment.

Figure 5.

MKC-3946 enhances MM cytotoxicity of bortezomib or 17-AAG, even in the presence of BMSCs or exogenous IL-6. (A-B) INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib (A) or 17-AAG (B) in combination with MKC-3946 0μM (□), 5μM (▩), or 10μM (■), in the presence or absence of BMSCs for 48 hours. (C-D) INA6 cells were treated with bortezomib (C) or 17-AAG (D) in combination with MKC-3946 0μM (□), 5μM (▩), or 10μM (■), with 2.5 ng/mL or 10 ng/mL of IL-6 for 48 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed by [3H]-thymidine uptake of quadruplicate cultures. Data represent the mean ± SD of [3H]-thymidine incorporation (CPM).

MKC-3946 alone or with bortezomib significantly inhibits growth of MM cells in vivo

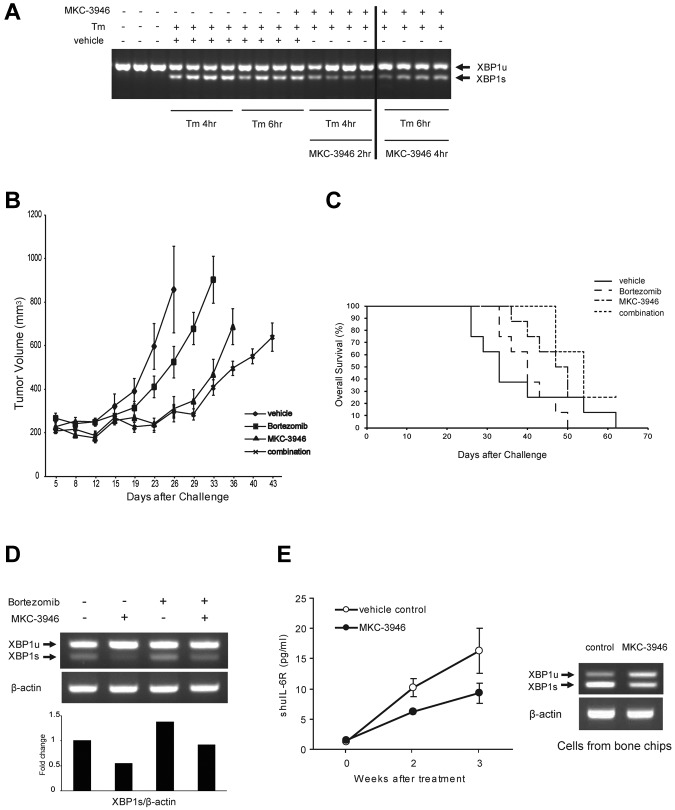

Finally, we studied the effect of MKC-3946 on MM cell growth in vivo. We first showed that MKC-3946 inhibited XBP1 splicing in a model of in vivo ER stress induced by Tm (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

MKC-3946 inhibits XBP1 splicing in a model of ER stress in vivo, associated with significant growth inhibition of MM cells, alone or with bortezomib. (A) SCID mice were treated with Tm (1 mg/kg intraperitoneally) for 4 or 6 hours. Two hours after Tm was administered, mice were treated with MKC-3946 50 mg/kg intraperitoneally. After 4-hour exposure to MKC-3946, mice were killed. Livers were harvested, and total RNA was prepared. RT-PCR was performed using murine-specific XBP1 primers. Each lane represents a single mouse. The vertical line indicates a repositioned gel lane. (B-D) SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 107 RPMI 8226 cells on day 0 and treated with 100 mg/kg MKC-3946 intraperitoneally daily (MKC-3946, n = 8), 0.15 mg/kg bortezomib intravenously twice a week (bortezomib, n = 8), or 100 mg/kg MKC-3946 intraperitoneally daily and 0.15 mg/kg bortezomib intravenously twice a week (combination, n = 8), for 21 days starting on day 1. A vehicle control group received intraperitoneal injections of vehicle and intravenous injection of saline (vehicle, n = 8). (B) Tumor volume was calculated from caliper measurements every 3 to 4 days, and data represent mean ± SE. (C) Survival in the plasmacytoma model was evaluated from the first day of treatment using Kaplan-Meier curves. (D) Total RNA was prepared from subcutaneous plasmacytoma harvested from each group of mice after 3 weeks of treatment. XBP1 and β-actin mRNA were examined using RT-PCR. The graph represents fold changes of XBP1s density relative to β-actin. (E) Growth of INA6 cells engrafted in human bone chips in SCID mice was monitored by serial serum measurements of shuIL-6R in the graph. Mice were treated with MKC-3946 100 mg/kg (n = 3) or control vehicle (n = 3), and shuIL-6R levels were determined weekly by ELISA. Error bars represent ± SE. Total RNA was prepared from tumor harvested from the MKC-3946– and control-treated SCID-hu mice at 3 weeks. XBP1 and β-actin mRNA were examined using RT-PCR in the right panel.

To evaluate the in vivo impact of MKC-3946 alone or in combination with bortezomib, we used the subcutaneous RPMI 8226 xenograft model of human MM in mice. MKC-3946 significantly reduced MM tumor growth in the treatment versus control group. For example, significant decrease in tumor growth in treated versus control mice was observed on day 26 (P < .05; Figure 6B). Importantly, MKC3946 in combination with low-dose bortezomib also significantly exhibited growth inhibition versus control (on day 26, P < .05) and versus low-dose bortezomib alone (on day 33, P < .001). Importantly, overall survival of MKC-3946 and low-dose bortezomib-treated mice was significantly prolonged versus control (P < .05) and versus low dose bortezomib alone (P < .001; Figure 6C). In addition, treatment with either MKC-3946 alone or combination with bortezomib did not affect body weight (supplemental Figure 6). We also confirmed by RT-PCR that MKC-3946 treatment significantly inhibited XBP1 splicing in the harvested tumors (Figure 6D; supplemental Figure 7).

To examine the activity of MKC-3946 on MM cell growth in the context of the human BM microenvironment in vivo, we used the SCID-hu model in which IL-6–dependent INA6 cells are directly injected into a human bone chip implanted subcutaneously in SCID-mice. These SCID-hu mice were then treated with MKC-3946 or vehicle alone daily for 3 weeks, and serum shuIL-6R was monitored as a marker of tumor burden. As shown in Figure 6E, MKC-3946 treatment for these weeks significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with vehicle control (P < .05). Moreover, XBP1 splicing of cells from the human bone chips was inhibited (Figure 6E right panel).

To examine why MKC-3946 treatment alone is effective in vivo, we compared expression of CHOP mRNA in MM cells in vitro versus in vivo. CHOP mRNA was significantly greater in vivo than in vitro in both RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells (supplemental Figure 8), suggesting more ER stress and enhanced cytotoxicity induced by MKC-3946 in vivo. Hypoxia can cause ER stress in MM cells in vivo because both solid tumors and the MM BM have been reported to be hypoxic.37,38 Importantly, MKC-3946 blocked XBP1 splicing in the setting of hypoxia-induced ER stress and inhibited growth of MM cells even under hypoxic conditions in vitro (supplemental Figure 9). These data suggest that MKC-3946 can be effective in vivo in the hypoxic MM BM.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that inhibition of XBP1 splicing by MKC-3946 is associated with decreased MM growth in vivo, alone or in combination with bortezomib.

Discussion

Because XBP1 is a transcription factor which regulates genes responsible for protein folding and degradation in the ER, IRE1α-XBP1 pathway has an adaptive function against ER stress. XBP1 is also one of the key mediators of MM cell pathogenesis.6,18,19 Here we show that XBP1u mRNA is expressed in all MM cell lines but that XBP1s mRNA is only detected in a subset of MM cell lines. Previous reports showed that XBP1s protein is expressed in MM patient cells and MM cell lines, such as MM1S and OPM1.19 We have confirmed that IRE1α-XBP1 pathway is essential for growth of MM cells by knockdown of XBP1. However, blockade of XBP1 splicing by MKC-3946 triggers only modest toxicity of MM cells in vitro. Together, these results suggest that reliance on XBP1s in these nonstressed in vitro culture conditions is minimal; however, our studies show that XBP1 levels are higher in vivo, where MKC-3946 demonstrates enhanced cytotoxicity both alone and in combination.

In this study, we demonstrated that XBP1 splicing is induced in ER stressed conditions triggered by bortezomib in RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells. Of note, prior data of the effect of bortezomib on XBP1 splicing are variable. Lee et al demonstrated that proteasome inhibitors, including bortezomib, prevented XBP1 splicing in J558 MM cells.18 Davenport et al showed that bortezomib had little effect on the induction of XBP1 splicing in U266 cells.13 We have confirmed that patterns of XBP1 mRNA splicing triggered by bortezomib vary in different cell lines. For example, MM1S cells exhibited minimum splicing of XBP1 induced by bortezomib treatment, whereas significant induction of XBP1 splicing by bortezomib was observed in both RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells. Importantly, inhibition of XBP1 splicing with MKC-3946 enhances cytotoxicity of bortezomib or 17-AAG via ER stress-mediated apoptosis, evidenced by up-regulation of CHOP. With bortezomib or 17-AAG treatment, unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, thereby enhancing ER stress.12,13 MM cells then attempt to adapt by means of the UPR, including activation of IRE1α and XBP1 splicing to promote protein folding homeostasis by induction of molecular chaperones or ERAD. Our studies show that MKC-3946 blocks this pathway, leading to enhancement of ER stress and ER stress-mediated apoptosis, alone and together with bortezomib or 17-AAG.

MKC-3946 did not inhibit the phosphorylation of IRE1α but did block XBP1 splicing. This may be advantageous because IRE1α kinase also has a proapoptotic role via the JNK pathway.10 Indeed, we demonstrated that binding of IRE1α to TRAF2 and phosphorylation of JNK were both enhanced by MKC-3946 treatment. Importantly, we did confirm that XBP1 target genes were also significantly inhibited by MKC-3946. Another IRE1α endoribonuclease inhibitor was recently reported to be potent MM therapy in vitro and in vivo,39 further suggesting the utility of this approach.

Our prior studies demonstrating that bortezomib and lenalidomide target MM cells in the BM milieu have translated from the bench to the bedside and FDA approval.40,41 Here we similarly evaluated the impact of the BM microenvironment on the antitumor activity of MKC-3946 using MM cells cocultured with BMSCs. MKC-3946 induced MM cytotoxicity, even in the presence of BMSCs or exogenous IL-6, suggesting that blocking constitutive and MM cell binding to BMSC-induced XBP1 splicing can inhibit growth and overcome conventional drug resistance in the BM milieu, further suggesting its potential clinical utility.

We also evaluated the in vivo efficacy of MKC-3946 in both our xenograft plasmacytoma and SCID-hu mouse models. Although MKC-3946 alone induced only modest cytotoxicity on MM cells in vitro, it significantly inhibited MM cell growth in vivo in both models, associated with inhibition of XBP1 splicing in tumors excised from treated mice. We hypothesize that this discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity is the result of different levels of ER stress in MM cells. XBP1 splicing in tumors excised from the control cohort was detected in both plasmacytoma and SCID-hu model; and especially in the SCID-hu model, basal XBP1s levels were higher than observed in vitro. Moreover, we confirmed that CHOP mRNA was significantly increased in both RPMI 8226 and INA6 cells in vivo versus in vitro. These results suggest that MM cells in vivo have more ER stress than in vitro and that inhibition of XBP1 splicing with MKC-3946 can therefore be more effective under in vivo stressed conditions. Hypoxia can cause ER stress in MM cells in vivo because both solid tumors and the MM BM have been reported to be hypoxic.37,38 Indeed, XBP1 is spliced under hypoxic conditions, and XBP1 is required for tumor growth in the hypoxic microenvironment in vivo.42,43 We demonstrated that MKC-3946 inhibited XBP1 splicing induced by hypoxia and also inhibited MM cell growth under in vitro hypoxic conditions. In addition, B cell–selective knockout studies have shown that XBP1 promotes BM colonization of plasma cells in vivo.44 XBP1s levels may therefore correspond to real-time stimuli, including oxygen levels and nutrients within the BM microenvironment in vivo. Importantly, MKC-3946 in combination with low-dose bortezomib significantly inhibited tumor growth in vivo in association with prolonged survival, suggesting potential clinical utility of this combination.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that blockade of XBP1 splicing by inhibition of IRE1α endoribonuclease domain using small-molecule inhibitor MKC-3946 triggers anti-MM activity and, importantly, enhances cytotoxicity of bortezomib or 17-AAG. Our results provide the preclinical framework for clinical trials of selective IRE1α inhibitors, alone or in combination with bortezomib, to improve patient outcome in MM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants SPORE-P50100707, PO1-CA078378, and RO1CA050947) and in part by the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (Biotech Investment Award). N.M. was a recipient of the International Myeloma Foundation Brian D. Novis Research Junior Grant Award. K.C.A. is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.F., D.C., L.S., Y.H., C.F., J.M., H.O., T.K., H.I., Y.K., and M.F. performed experiments; G.G. and Y.-T.T. analyzed data; M.B., V.T., N.L.K., U.M.M., M.H., T.P., and Q.Z. contributed the vital new reagent; J.B.P. contributed the vital new reagent, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; P.G.R. and N.C.M. designed research and provided clinical samples; and K.C.A. designed research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.T., U.M.M., Q.Z., and J.B.P. are employees at MannKind. P.G.R. serves on advisory boards to Millennium, Celgene, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. N.C.M. serves on advisory boards to Millennium, Celgene, and Novartis. K.C.A. serves on advisory boards to Millennium, Onyx, and MannKind. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kenneth C. Anderson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Mayer 557, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: kenneth_anderson@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Laubach J, Richardson P, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62(2011):249–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070209-175325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palumbo A, Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1046–1060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111(5):2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schröder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim I, Xu W, Reed JC. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(12):1013–1030. doi: 10.1038/nrd2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todd DJ, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(9):663–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107(7):881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(21):7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(4):1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287(5453):664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. The X-box binding protein-1 transcription factor is required for plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:29–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ, Jr, Lee KP, Boise LH. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107(12):4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport EL, Moore HE, Dunlop AS, et al. Heat shock protein inhibition is associated with activation of the unfolded protein response pathway in myeloma plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110(7):2641–2649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-053728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson B, Brewer JW, Hendershot LM. Geldanamycin, an hsp90/GRP94-binding drug, induces increased transcription of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones via the ER stress pathway. J Cell Physiol. 1998;174(2):170–178. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199802)174:2<170::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcu MG, Doyle M, Bertolotti A, Ron D, Hendershot L, Neckers L. Heat shock protein 90 modulates the unfolded protein response by stabilizing IRE1alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(24):8506–8513. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8506-8513.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koong AC, Chauhan V, Romero-Ramirez L. Targeting XBP-1 as a novel anti–cancer strategy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5(7):756–759. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munshi NC, Hideshima T, Carrasco D, et al. Identification of genes modulated in multiple myeloma using genetically identical twin samples. Blood. 2004;103(5):1799–1806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Anderson KC, Glimcher LH. Proteasome inhibitors disrupt the unfolded protein response in myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(17):9946–9951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1334037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrasco DR, Sukhdeo K, Protopopova M, et al. The differentiation and stress response factor XBP-1 drives multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(4):349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M, Gotoh T, Okuno Y, et al. Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway is associated with survival of myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(3):531–539. doi: 10.1080/10428190500312196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagratuni T, Wu P, Gonzalez de Castro D, et al. XBP1s levels are implicated in the biology and outcome of myeloma mediating different clinical outcomes to thalidomide-based treatments. Blood. 2010;116(2):250–253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volkmann K, Lucas JL, Vuga D, et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 endoribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(14):12743–12755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hideshima T, Catley L, Yasui H, et al. Perifosine, an oral bioactive novel alkylphospholipid, inhibits Akt and induces in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107(10):4053–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda H, Hideshima T, Fulciniti M, et al. The monoclonal antibody nBT062 conjugated to cytotoxic Maytansinoids has selective cytotoxicity against CD138-positive multiple myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(12):4028–4037. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hideshima T, Neri P, Tassone P, et al. MLN120B, a novel IkappaB kinase beta inhibitor, blocks multiple myeloma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5887–5894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Blood. 2003;101(4):1530–1534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cirstea D, Hideshima T, Rodig S, et al. Dual inhibition of akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway by nanoparticle albumin-bound-rapamycin and perifosine induces antitumor activity in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(4):963–975. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Kiziltepe T, et al. Biologic sequelae of IkappaB kinase (IKK) inhibition in multiple myeloma: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2009;113(21):5228–5236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-161505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urashima M, Chen BP, Chen S, et al. The development of a model for the homing of multiple myeloma cells to human bone marrow. Blood. 1997;90(2):754–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda H, Hideshima T, Fulciniti M, et al. PI3K/p110delta is a novel therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116(9):1460–1468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-222943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knight BC, High S. Membrane integration of Sec61alpha: a core component of the endoplasmic reticulum translocation complex. Biochem J. 1998;331(1):161–167. doi: 10.1042/bj3310161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008;320(5882):1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Huizen R, Martindale JL, Gorospe M, Holbrook NJ. P58IPK, a novel endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible protein and potential negative regulator of eIF2alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(18):15558–15564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Meunier L, Hendershot LM. Identification and characterization of a novel endoplasmic reticulum (ER) DnaJ homologue, which stimulates ATPase activity of BiP in vitro and is induced by ER stress. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(18):15947–15956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong M, Bridges JP, Apsley K, Xu Y, Weaver TE. ERdj4 and ERdj5 are required for endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation of misfolded surfactant protein C. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(6):2620–2630. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colla S, Storti P, Donofrio G, et al. Low bone marrow oxygen tension and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha overexpression characterize patients with multiple myeloma: role on the transcriptional and proangiogenic profiles of CD138(+) cells. Leukemia. 2010;24(11):1967–1970. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin SK, Diamond P, Gronthos S, Peet DJ, Zannettino AC. The emerging role of hypoxia, HIF-1 and HIF-2 in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2011;25(10):1533–1542. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papandreou I, Denko NC, Olson M, et al. Identification of an Ire1alpha endonuclease specific inhibitor with cytotoxic activity against human multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117(4):1311–1314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson KC. Targeted therapy of multiple myeloma based upon tumor-microenvironmental interactions. Exp Hematol. 2007;35(4 Suppl 1):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podar K, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Bone marrow microenvironment and the identification of new targets for myeloma therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):10–24. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero-Ramirez L, Cao H, Nelson D, et al. XBP1 is essential for survival under hypoxic conditions and is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):5943–5947. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwakoshi NN, Pypaert M, Glimcher LH. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2267–2275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu CC, Dougan SK, McGehee AM, Love JC, Ploegh HL. XBP-1 regulates signal transduction, transcription factors and bone marrow colonization in B cells. EMBO J. 2009;28(11):1624–1636. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.