Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP) across decades and regions.

Methods

Electronic PubMed/Google Scholar search for studies reporting on APP, published from 1970-05/2009. Median rates and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated and compared using non-parametric tests. Demographic and clinical variables were tested as correlates of APP in bivariate and meta-regression analyses.

Results

Across 147 studies (1,418,163 participants, 82.9% diagnosed with schizophrenia [IQR=42–100%]), the median APP rate was 19.6% (IQR=12.9–35.0%). Most common combinations included first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)+second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (42.4%, IQR=0.0–71.4%) followed by FGAs+FGAs (19.6%, IQR=0.0–100%) and SGAs+SGAs (1.8%, IQR=0.0–28%). APP rates were not different between decades (1970–1979:28.8%, IQR=7.5–44%; 1980–1989:17.6%, IQR=10.8–38.2; 1990–1999:22.0%, IQR=11–40; 2000–2009:19.2% IQR=14.4–29.9, p=0.78), but between regions, being higher in Asia and Europe than North America, and in Asia than Oceania (p<0.001). APP increased numerically by 34% in North America from the 1980s 12.7%) to 2000s (17.0%) (p=0.94) and decreased significantly by 65% from 1980 (55.5%) to 2000 (19.2%) in Asia (p=0.03), with non-significant changes in Europe. APP was associated with inpatient status (p<0.001), use of FGAs (p<0.0001) and anticholinergics (<0.001), schizophrenia (p=0.01), less antidepressant use (p=0.02), greater LAIs use (p=0.04), shorter follow-up (p=0.001) and cross-sectional vs. longitudinal study design (p=0.03). In a meta-regression, inpatient status (p<0.0001), FGA use (0.046), and schizophrenia diagnosis (p=0.004) independently predicted APP (N=66, R2=0.44, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

APP is common with different rates and time trends by region over the last four decades. APP is associated with greater anticholinergic requirement, shorter observation time, greater illness severity and lower antidepressant use.

Keywords: Combinations, Schizophrenia, Polypharmacy, Cotreatment, Meta-regression

1. Introduction

The use of two or more antipsychotic medications, also called “antipsychotic polypharmacy” (APP), is common (Faries et al., 2005), having been criticized due to the limited evidence supporting its use (Stahl, 1999a, b). Compared to antipsychotic monotherapy, APP has been associated with increased hospitalization rates and length of stay (Centorrino et al., 2004; Gilmer et al., 2007), adverse effects (Jerrell and McIntyre, 2008; McIntyre and Jerrell, 2008), antipsychotic doses (Bingefors et al., 2003; Elie et al., 2009; Hung and Cheung, 2008), treatment cost (Rupnow et al., 2007; Stahl and Grady, 2006), and mortality rates (Joukamaa et al., 2006; Waddington et al., 1998). However, not all studies have found negative effects of APP. A recent meta-analysis found superiority of APP compared to monotherapy regarding “study-defined” efficacy (Correll et al., 2009); however, most included studies were clozapine-augmentation studies. A second meta-analysis of antipsychotic augmentation studies of clozapine only found superiority of APP in open, but not in blinded studies (Barbui et al., 2009). In both meta-analyses, insufficient data on psychopathology and side effect rates precluded meaningful analyses. Moreover, few studies attempted to change patients from APP to monotherapy. In three such studies, 50–67% of patients on APP were able to tolerate conversion to monotherapy (Suzuki et al., 2004a; Suzuki et al., 2004b; Essock et al., 2011).

Despite the frequency and debated nature of APP, the prevalence and correlates of APP have not been systematically reviewed across geographic regions and decades. Prior reviews either did not systematically review all literature (Ananth et al., 2004) or focused only on restricted areas of interest, including SGAs (Pandurangi and Dalkilic, 2008), schizophrenia (Messer et al., 2006), bipolar disorder (Zarate and Quiroz, 2003), efficacy, and adverse effects (Tranulis et al., 2008).

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

An electronic PubMed and Google scholar search without restrictions regarding language, diagnosis, antipsychotic type, treatment setting, or geographic region was conducted for articles published between 1970 and May 2009. For the search, the Boolean operator “AND” was used to connect the word “antipsychotics” with each of the following seven words: “polypharmacy”, “comedications”, “coprescription”, “concomitant”, “cotreatment”, “combination”, and “adjunctive”. Reference lists from retrieved articles were reviewed to identify additional studies.

2.2. Study Selection

Studies that reported on the frequency of APP, i.e., the concomitant use of ≥2 antipsychotics (excluding the combination of an LAI with the same oral antipsychotic), in patients aged >18 years were included. Excluded were also: 1) intervention studies aimed at decreasing APP; 2) studies reporting on psychotropic polypharmacy, without specific information on APP. When studies reported in a single article more than one APP rate assessed at different times, we entered these APP rates as different observations or “time points”. Articles in different languages were translated by the investigators: JZ (Chinese), JG (Spanish and Italian), CC (German and French).

2.3. Data Extraction

Design, demographic, treatment, setting and illness variables were extracted independently by three investigators (JG, JB, CC). Although overlapping conceptually, the terms “mood stabilizers”, “anticonvulsants” and “lithium” were taken directly from the publications.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Due to non-normally distributed data, non-parametric tests were used. Continuous variables were described using medians and interquantile ranges (IQR) and differences between groups were examined using Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Post-hoc tests were conducted using a rank test corrected for multiple comparisons (Siegel and Castellan, 1988). Correlations were examined using the Spearman correlation coefficient and comparisons between categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher exact test. Analyses were conducted using STATA version 11 (StataCorp. 2009. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Further details about methods regarding the analysis by geographic region (2.5.), decade (2.6.), illness severity proxy variables (2.7.), required APP duration (2.8.) and of the meta-regression analysis (2.9.) are reported in Supplemental File 1.

3. Results

3.1. Database

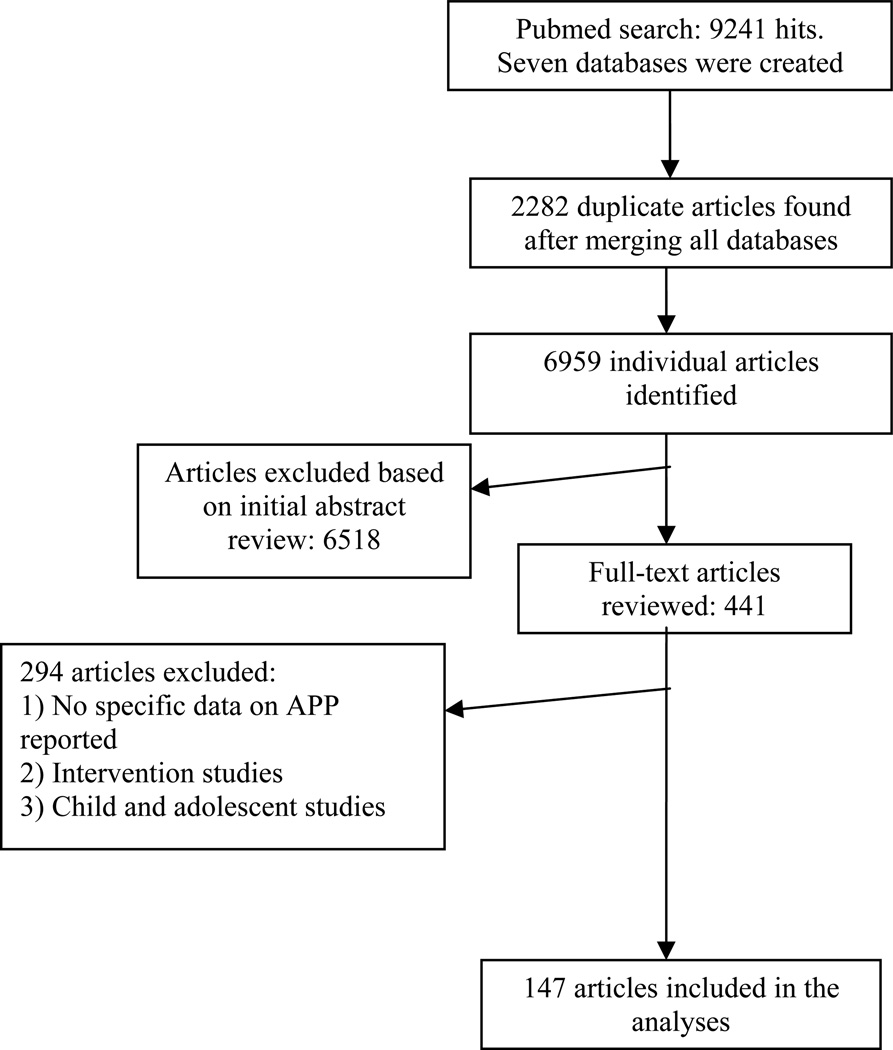

Of the 9,241 articles initially identified, only 147 were included in the final analyses (Figure 1; Supplemental file 1; Supplemental file 2).

Figure 1.

Quality of Research of Meta-analysis (QUORUM) flow chart.

3.2. Study characteristics

147 studies, reporting APP rates for 196 individual time points in a total of 1,418,163 patients (median=399 patients per study, IQR=157–1999, range=16–671,454), were analyzed (Table 1). 108 studies (73.5%) were cross-sectional and 39 (26.5%) were longitudinal, 31.9% were conducted in academic institutions, 60.4% were conducted only in urban areas, 80.3% gathered the clinical data from multiple sources (pharmacy claims, administrative claims, physician questionnaires, chart, etc) and 51.5% involved only inpatients. All but 20 studies (13.6%) used a cross-sectional definition of APP, measuring cotreatment only at a single time point. There were no significant differences in study characteristics across geographic regions. Overall, 82 (41.8 %) APP rates were reported in the 1990s, 67 (34.2%) in the 2000s, 35 (17.9%) in the 1980s and 12 (6.1%) in the 1970s. The number of APP rate reports was significantly different between regions in individual decades (p<0.001 for each decade) and for the number of assessment time points across regions in the 1970–1995 period vs. the 1996–2009 period (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prescribing characteristics by geographic region

| Study and Patient Characteristics | All regions | North America |

Asia | Europe | Oceania | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Characteristics | Fisher’s exact test | |||||

| Total Number of studies, n (%) | 147 (100) | 52 (35.4) | 13 (8.8) | 74 (50.3) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Data Source, n (%) | 132(100) | |||||

| From patient interview | 26 (19.7) | 7 (14.9) | 4 (30.8) | 13 (19.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0.4 |

| Other sources | 106 (80.3) | 40 (85.1) | 9 (69.2) | 53 (80.3) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Location, n (%) | 91(100) | |||||

| Urban | 55 (60.4) | 13 (46.4) | 10 (90.9) | 29 (60.4) | 3 (75.0) | 0.06 |

| Mixed (urban and rural) | 36 (39.6) | 15 (53.6) | 1 (9.1) | 19 (39.6) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Institution type, n (%) | 91(100) | |||||

| University-teaching | 29 (31.9) | 10 (27.0) | 4 (40.0) | 14 (36.8) | 1 (16.7) | 0.7 |

| Mixed | 62 (68.1) | 27 (73.0) | 6 (60.0) | 24 (63.2) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Study design, n (%) | 147(100) | |||||

| Cross sectional | 108 (73.5) | 34 (65.4) | 12 (92.3) | 55 (74.3) | 7 (87.5) | 0.2 |

| Longitudinal | 39(26.5) | 18 (34.6) | 1 (7.7) | 19 (25.7) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Setting, n (%) | 132(100) | |||||

| Inpatient | 68 (51.5) | 16 (36.4) | 7 (58.3) | 43 (63.2) | 2 (25.0) | 0.051 |

| Outpatient | 42 (31.8) | 17 (38.6) | 3 (25.0) | 17 (25.0) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Mixed | 22 (16.7) | 11 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 8 (11.8) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Patient Characteristics | Kruskal-Wallis | |||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Total number of time points*, n (%) | 196(100) | 65(33.2) | 17(8.7) | 103(52.6) | 11(5.6) | |

| Number of patients (total) | 1,418.136 | 586,788 | 17,147 | 796,614 | 17,587 | |

| Number of patients (Median, IQR)[*] | 399.0(157.0–1999)[196] | 741.0(282.0–3184.0)[65] | 491.0(139.0–957.0)[17] | 293.0(121.0–811.0)[103] | 2057.0(364.0–2418.0)[11] | 0.004 |

| Age yrs | 40.9(38.0–44.7)[124] | 42.2 (39.0–46.0)[n=34] | 41.3(30.1–43.6) [n=17] | 40.0(38.0–45.7) [n=64] | 39.0(38.0–40.0) [n=9] | 0.23 |

| White % | 54.0(39.0–76.0)[33] | 52.0 (43.0–70.5) [n=20] | 0.0(0.0–0.0) [n=4] | 84.0(60.0–99.0)[n=9] | - [n=0] | <0.001 |

| Male % | 55.0(48.0–63.9)[155] | 55.0(49.0–65.0) [n=42] | 59.0(54.0–61.8)[n=17] | 54.0(45.0–62.3) [n=85] | 63.8(59.0–67.1)[n=11] | 0.1 |

| Schizophrenia diagnosis % | 82.9(42.0–100)[130] | 96.0(52.7–100) [n=40] | 100(100–100) [n=12] | 59.4(40.0–100) [n=69] | 86.0(83.7–100)[n=9] | 0.002 |

| Illness duration yrs | 14.0(9.5–16.4)[37] | 18.2(14.7–20.4)[n=4] | 13.2(0.5–15.8)[n=12] | 13.2(9.8–16.7) [n=20] | 15.0(15.0–15.0) [n=1] | 0.27 |

| Psychopathology | ||||||

| CGI severity score (Median, IQR) [*] | 5.5(5.0–5.8) [6] | 5.5(5.2–5.7) [4] | - [0] | 5.1(3.8–6.4) [2] | - [n=0] | >0.9 |

| PANSS total score | 87.5(63.1–89.0)[5] | 76.5(57.2–95.8) [n=2] | 63.1(63.1–63.1)[n=1] | 88.3(87.5–89.0) [n=2] | - [n=0] | 0.74 |

| PANSS positive score | 18.9(15.3–21.1)[4] | 13.8(13.8–13.8) [n=1] | - [n=0] | 21.0(16.8–21.2) [n=3] | - [n=0] | 0.18 |

| PANSS negative score | 20.6(18.1–22.6)[4] | 17.0(17.0–17.0)[n=1] | - [n=0] | 22.1(19.1–23.0)[n=3] | - [n=0] | 0.18 |

| BPRS total score | 39.9(25.3–46.0)[6] | 34.2(25.3–47.0)[n=3] | -[n=0] | 45.5(24.4–46.0) [n=3] | - [n=0] | 0.83 |

| BPRS psychosis score | 13.9(8.1–35.0)[3] | - [n=0] | -[n=0] | 13.9(8.1–35.0) [n=3] | - [n=0] | N/A |

| GAF score | 55.1(43.5–59.2)[4] | 50.9(50.9–50.9)[n=1] | 59.2(59.2–59.2)[n=1] | 47.6(36.0–59.2) [n=2] | - [n=0] | 0.66 |

| Time points by Decade^ | 196 | 65 | 17 | 103 | 11 | Kruskal-Wallis |

| 1970–1979 n, (% per decade) | 12 (100%) | 7 (58.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| 1980–1989 | 35 (100%) | 3 (8.6) | 2 (5.7) | 29 (82.9) | 1 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| 1990–1999 | 82 (100%) | 30 (36.6) | 6 (7.3) | 42 (51.2) | 4 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| 2000–2009 | 67 (100%) | 25 (37.3) | 9 (13.4) | 27 (40.3) | 6 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| 1970–1995 | 73 (100%) | 14 (19.2) | 3 (4.1) | 54 (74.0) | 2 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| 1996–2009 | 127 (100%) | 51 (41.5) | 14 (11.4) | 49 (39.8) | 9 (7.3) | <0.001 |

Number of time points: some studies reported in a single article two or more APP rates examined in different points in time (e.g. 1999 and 2000), constituting two or more different individual samples in our database.

Due to missing information in some reports, the percentages describing the study and patient characteristics in each geographic region may be based on a lower number of studies than the total number of studies per region.

Studies were classified based on time of data collection as opposed of publication date. CGI: Clinical Global Impressions Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. IQR: Interquantile range (percentile 25–75).

3.3. Patient characteristics

The median patient age was 40.9 years (IQR=38.0–44.7). 55% (IQR=48–63.9) were male and 54% were white (IQR=39.0–76.0) with most patients (82.9% [IQR=42–100]) being diagnosed with schizophrenia. The proportion of patients with schizophrenia (lowest in Europe, p=0.002) and of Whites (highest in Europe, p<0.001) was significantly different between geographic regions. Patients were followed up for longer periods of time in North America compared to the other regions (p=0.004). Only between 3 (1.5%) and 6 (3.1%) of assessment time points also reported on psychopathology measures, without significant group differences (Table 1).

3.4. Prescribing characteristics

The pooled median APP rate was 19.6% (IQR=12.9–35.0%) across all regions and decades. The most common combination included first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)+SGAs (42.4%, IQR=0.0–71.4%) followed by FGAs+FGAs (19.6%, IQR=0.0–100%) and SGAs+SGAs (1.8%, IQR=0.0–28%). The majority of patients (68%, IQR=52.8–82.9%) in samples for which APP rates were reported were taking one antipsychotic, 17.8% (IQR=10.5–32-7%) were taking two and 0.2% (IQR=0.0–4.7) were taking ≥3 antipsychotics (Table 2). Data on individual medication frequencies are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Psychotropic medication prescribing practices by geographic region

| Treatment Characteristics | No. of time points^ | All regions | North America (NA) | Asia (AS) |

Europe (E) | Oceania (O) | P value* | Post-Hoc** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | ||||||||

| 0 Antipsychotic % (Median, IQR) | 158 | 0.0(0.0–10.0) | 0.0(0.0–1.2) | 1.0(0.0–3.2) | 0.0(0.0–16.3) | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.18 | |

| 1 Antipsychotic | 158 | 68.0(52.8–82.9) | 80.1(63.4–85.3) | 63.4(40.0–77.3) | 60.0(46.2–73.0) | 81.7(78.0–85.4) | <0.001 | NA>E |

| 2 Antipsychotics | 90 | 17.8(10.5–32.7) | 13.9(6.6–26.0) | 26.7(22.3–40.4) | 19.8(10.5–35.0) | 14.9(13.4–17.1) | 0.06 | |

| 3 or more Antipsychotics | 90 | 0.2(0.0–4.7) | 0.0(0.0–2.0) | 1.9(0.0–15.7) | 0.0(0.0–6.0) | 0.6(0.0–0.9) | 0.40 | |

| APP (>/= 2 Antipsychotics)a | 196 | 19.6(12.9–35.0) | 16.0(7.23–24.4) | 32(19.2–53.0) | 23.0(15.0–42.1) | 16.4(9.8–20.0) | <0.001 | AS, E>NA; AS>O |

| First-generation antipsychotics | 139 | 51.0(33.0–86.4) | 44.0(23.6–54.9) | 73.1(67.0–97.0) | 54.6(40.0–90.0) | 40.5(26.0–56.0) | 0.002 | AS, E>NA. |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | 131 | 53.0(13.6–86.6) | 59.0(27.0–89.6) | 28.0(13.6–61.9) | 46.0(3.5–94.5) | 68.7(58.9–82.0) | 0.32 | |

| Clozapine | 97 | 7.0(0.0–19.6) | 2.0(0.0–10.5) | 14.8(0.6–17.0) | 8.5(0.0–23.0) | 21.0(15.5–35.0) | 0.01 | O>NA |

| Long-acting injectable preparations | 65 | 23.2(14.6–41.8) | 13.0(0.0–23.0) | 33.2(22.1–46.2) | 24.0(16.0–54.0) | 24.8(23.3–26.0) | 0.04 | E>NA |

| Comedications | ||||||||

| Mood stabilizers b | 40 | 17.7(7.5–27.9) | 27.7(14.2–30) | 4.3(1.0–7.0) | 17.7(10.5–26.0) | 27.3(22.6–32.0) | 0.007 | NA>AS |

| Lithium b | 49 | 5.5(3.0–10.8) | 6.9(1.0–12.8) | 3.1(1.9–4.0) | 6.1(4.0–10.0) | 15.0(13.0–17.0) | 0.09 | |

| Anticonvulsants b | 40 | 7.0(3.3–13.1) | 24.6(10.7–44.0) | 6.3(4.3–9.0) | 5.7(1.0–8.9) | 8.0(3.0–13.0) | 0.01 | NA>E |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 94 | 33.8(19.6–53.0) | 23.1(13.1–34.0) | 24.3(8.6–30.0) | 38.4(28.6–65.9) | 23.5(8.0–39.0) | 0.003 | E>NA |

| Antidepressants | 98 | 19.1(10.0–30.6) | 19.3(7.0–29.0) | 7.0(5.9–11.3) | 24.0(11.0–35.6) | 24.7(18.0–47.0) | 0.006 | E>AS |

| Anticholinergics | 94 | 30.9(20.0–46.8) | 33.0(20.0–41.9) | 63.0(47.0–67.2) | 27.5(19.0–41.3) | 3.0(3.0–3.0) | 0.001 | AS>NA,E |

| APP (>/= 2 Antipsychotics) | ||||||||

| FGA + FGA | 98 | 19.6(0.0–100) | 0.0(0.0–23.2) | 42.2(0.0–58) | 66.8(0.0–100) | 55.4(37.0–100) | 0.04 | E>NA |

| SGA + SGA | 94 | 1.8(0.0–28) | 21.0(0.0–55.5) | 2.1(0.0–7.3) | 0.0(0.0–7.2) | 2.3(0.0–2.3) | 0.007 | NA>E |

| FGA + SGA | 106 | 42.4(0.0–71.4) | 52.6(0.0–74.1) | 36.5(8.2–79.7) | 36.4(0.0–84.4) | 42.2(4.5–53.7) | 0.8 | |

| Long-acting injectable preparations | 29 | 57.2(13.6–100) | 0.0(0.0–25.0) | 57.2(57.2–57.2) | 80.0(25.0–100) | 54.2(8.4–100) | 0.09 |

Number of time points: some studies reported in a single article two or more APP rates, examined at different points in time (e.g. 1999 and 2000), constituting two or more different individual samples in our database. Total Number of studies: 147. Total number of time points: 196.

Kruskal Wallis test.

Using a rank test corrected for multiple comparisons at p<0.05. APP: Antipsychotic Polypharmacy. FGA: First-Generation Antipsychotic. SGA: Second-Generation Antipsychotic. IQR: Interquantile range (percentile 25–75).

The APP rate is not identical to the sum of patients taking 2 or >/=3 antipsychotics, as not all studies reporting on APP specified the exact number of antipsychotics prescribed;

Although overlapping conceptually, the terms “mood stabilizers”, “anticonvulsants” and “lithium” are taken directly from the publications.

3.4.1. Prescribing characteristics by geographical region

Pooled APP rates were significantly lower in North America (16%, IQR=7.2–24.4%) compared to Asia (32%, IQR=19.2–53.0%) and Europe (23%, IQR=15.0–42.1%) (p<0.001). Similarly, the APP rate was significantly higher in Asia (32%, IQR=19.2–53%) than Oceania (16.4%, IQR=9.8–20.0) (p<0.001) (Table 2). The use of one antipsychotic (p<0.001), two SGAs (p=0.007), and concomitant anticonvulsants (p=0.01) was significantly higher in North America compared to Europe. The use of mood stabilizers was also significantly higher in North America compared to Asia (p=0.007). Asia had significantly higher rates of anticholinergic use (63.0%, IQR=47.0–67.2%) compared to North America (33.0%, IQR=20.0–41.9) and Europe (27.5%, IQR=19.0–41.3) (p=0.001). The use of FGAs was significantly higher in Asia and Europe compared to North America (p=0.002). Europe had significantly higher prescription rates of LAI preparations (p=0.04), two FGAs (p=0.04), and concomitant anxiolytics (p=0.003) than North America. The use of clozapine was significantly higher in Oceania compared to North America (p=0.01). The use of concomitant antidepressants was less common in Asia compared to Europe (p=0.006) (Table 2).

3.4.2. Prescribing characteristics by decade

There were no statistically significant differences in APP rates between decades (p=0.78) (Table 3). However, expectedly due to the wide introduction of SGAs only after 1990, the rate of individual antipsychotic class combinations was significantly different between decades, with the combination of two FGAs being more common in the 1970s and 1980s (p<0.001), and the combination of FGA+SGA and two SGAs being more common in 1990s and 2000s (p<0.001). Similarly, the use of FGAs was significantly higher in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s (p<0.001), whereas the use of SGAs was significantly higher in the 1990s and 2000s (p<0.001). The use of one antipsychotic was significantly higher in the 2000s compared to the 1970s and 1980s (p=0.001), while the use of no antipsychotic was significantly higher in 1980s compared to the 2000 decade (p<0.001). The use of clozapine was significantly higher in the 1990s and 2000s compared to the 1970s and 1980s (p<0.001). The use of anticonvulsants was significantly higher in the 1990s compared to 1980s (p=0.04), and LAI use combined with other antipsychotics (p=0.047) was also significantly higher in the 1970s and 1980s compared to 1990s and the 2000 decade (Table 3).

Table 3.

Psychotropic medication prescribing practices over time

| Treatment Characteristics | No. of TP* |

1970–1979 (1) | 1980–1989 (2) | 1990–1999 (3) | 2000–2009 (4) | P value+ |

Post- Hoc++ |

<1996 | ≥1996 | P value^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | ||||||||||

| 0 Antipsychotic (median, IQR) | 158 | 13.8(0.0–42.5) | 6.0(0.0–39.0) | 0.0(0.0–4.3) | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.003 | 2>4 | 6.0(0.0–23.9) | 0.0(0.0–1.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 Antipsychotic | 158 | 44.0(41.0–51.3) | 56.2(40.0–67.4) | 70.8(54.5–82.4) | 77.7(60.7–84.1) | <0.001 | 4,3>1; 4>2 | 56.2(41.8–70) | 75.0(59.0–84.0) | <0.001 |

| 2 Antipsychotics | 90 | 26.0(6.2–41.0) | 14.7(4.5–31.0) | 19.3(12.8–32.2) | 17.1(12.4–34) | 0.62 | - | 16.5(5.5–34.3) | 18.7(12.8–31.7) | 0.33 |

| 3 or more Antipsychotics | 90 | 2.0(0.0–13.0) | 0.0(0.0–4.7) | 2.7(0.0–8.3) | 0.0(0.0–1.2) | 0.15 | - | 0.0(0.0–5.0) | 0.2(0.0–4.2) | 0.90 |

| APP (≥2 Antipsychotics) a | 196 | 28.8(7.5–44.4) | 17.6(10.8–38.2) | 22.0(11.0–40.0) | 19.2(14.4–29.9) | 0.78 | - | 19.0(10.8–40.0) | 19.8(14.1–34.0) | 0.90 |

| First-generation antipsychotics | 139 | 88.4(56.0–100) | 86.8(55.9–100) | 53.0(38.5–88.0) | 40.5(21.7–51.0) | <0.001 | 1,2,3>4 | 88.2(56.0–100) | 44.0(28.0–53.0) | <0.001 |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | 131 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.0(0.0–1.0) | 56.0(24–100) | 67.9(46–86.6) | <0.001 | 4,3>1,2 | 0.0(0.0–23.4) | 67.6(45.0–89.6) | <0.001 |

| Clozapine | 97 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.0(0.0–6.5) | 11.9(6.2–23.3) | 13.6(3.3–19.6) | <0.001 | 4,3>1,2 | 0.0(0.0–11.7) | 13.5(5.8–21.0) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting Injectable preparation | 65 | 62.1(13.4–100) | 25.4(11.0–58.0) | 23.3(18.0–35.0) | 19.4(8.7–22.9) | 0.24 | - | 25.2(11.0–54.0) | 22.7(17–26.9) | 0.47 |

| Comedications | ||||||||||

| Mood stabilizers b | 40 | None | 5.0(3.0–17.7) | 20.3(10.9–27.7) | 16.7(7.0–31.1) | 0.24 | - | 6.5(5.0–17.7) | 20.0(10.5–30.0) | 0.07 |

| Lithium b | 49 | 3.7(0.8–8.0) | 9.0(3.7–12.3) | 5.2(3.2–11.8) | 4.2(3.0–6.1) | 0.32 | - | 8.0(3.7–12.3) | 4.7(2.9–7.7) | 0.13 |

| Anticonvulsants b | 40 | 7.0(0.0–10.7) | 3.5(0.0–8.0) | 10.1(6.3–20.7) | 10.0(5.7–13.1) | 0.04 | 3>2 | 5.6(2.0–9.0) | 10.0(6.9–23.0) | 0.02 |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 94 | 15.0(8.2–71.0) | 31.2(16.0–38.8) | 39.5(21.8–51.8) | 35.1(24.8–62.1) | 0.38 | - | 33.1(15.0–51.1) | 36.2(23.6–57.3) | 0.30 |

| Antidepressants | 98 | 9.0(5.3–21.5) | 14.1(9.8–30.7) | 21.4(10.6–27.3) | 28.8(12.5–38.1) | 0.08 | - | 15.5(9.0–28.0) | 22.2(11.3–33.3) | 0.14 |

| Anticholinergics | 94 | 38.7(23.0–72.1) | 37.0(26.9–48.3) | 30.0(21.3–41.9) | 23.9(15.5–44.6) | 0.36 | - | 37.0(21.6–51.0) | 27.5(17.9–41.9) | 0.06 |

| APP (>/=2 Antipsychotics) | ||||||||||

| FGA + FGA | 98 | 100(100–100) | 100(100–100) | 0.0(0.0–55.4) | 0.0(0.0–12.0) | <0.001 | 1,2>3,4 | 100(100–100) | 0.0(0.0–17.2) | <0.001 |

| SGA + SGA | 94 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 4.1(0.0–23.5) | 28.5(8.3–55.5) | <0.001 | 3,4>1,2 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 16.6(2.0–42.5) | <0.001 |

| FGA + SGA | 106 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 0.0(0.0–0.5) | 50.0(10.0–85.7) | 57.5(39.5–69.9) | <0.001 | 3,4>1,2 | 0.0(0.0–0.0) | 57.5(39.0–79.0) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting injectable preparation | 29 | 100(100–100) | 80.0(13.6–100) | 25.0(8.4–81.0) | 25.0(16.4–31.8) | 0.047 | 1,2>3,4 | 81.0(13.6–100) | 25.0(12.0–40.7) | 0.04 |

Number of time points: some studies reported in a single article two or more APP rates, examined at different points in time (e.g. 1999 and 2000), constituting two or more different individual samples in our database. Total Number of studies: 147. Total number of time points: 196.

Kruskal Wallis test.

Using a rank test corrected for multiple comparisons at p<0.05.

Mann-Whitney test. APP: Antipsychotic Polypharmacy. FGA: First-Generation Antipsychotic. SGA: Second-Generation Antipsychotic. IQR: Interquantile range (percentile 25–75).

The APP rate is not identical to the sum of patients taking 2 or ≥3 antipsychotics, as not all studies reporting on APP specified the exact number of antipsychotics prescribed;

Although overlapping conceptually, the terms “mood stabilizers”, “anticonvulsants” and “lithium” are taken directly from the publication

LAI use combined with oral antipsychotics (p=0.04) and, expectedly, use of FGAs (p<0.001) and of two FGAs (p<0.001) was significantly higher in the period up </=1995. Conversely, the use of one antipsychotic (p<0.001), anticonvulsants (p=0.02), SGAs (p<0.001), clozapine (p<0.001), two SGAs (p<0.001) and FGA+SGA combinations (p<0.001) was significantly higher after 1995 (Table 3).

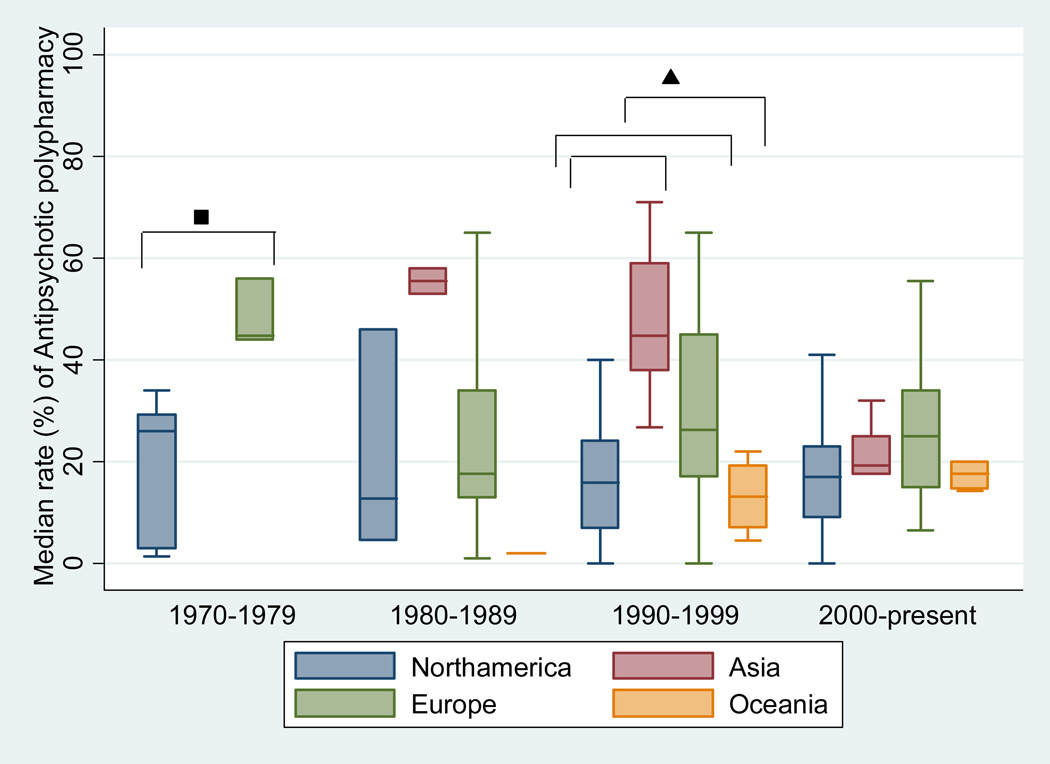

3.4.3. Distribution of APP by geographic region and decade

APP in North America increased numerically by 34% since 1980s (12.7%, IQR=4.5–46%) to 2000 (17%, IQR=9.1–23%) (p=0.94) (Figure 2). Oceania had an even a larger increase in APP from 2% (IQR=2-2) in the 1980s to 17.7% (IQR=14.6–20%) in the 2000s (p=0.18). Conversely, APP decreased in Asia by 65% from 1980 (55.5%) to 2000 (19.2%) (p=0.03) and increased in Europe in the 1990s, decreasing slightly in the 2000s. Specifically, except for Asia (p=0.03), there were no significant decade-specific APP differences in North America (p=0.94), Europe (p=0.1) and Oceania (p=0.18) across all four decades (overall p=0.94). However, there were significant regional differences within specific decades. In the 1970s, the APP was significantly higher in Europe (44.7%, IQR=44.0–56.0%) than in North America (26.0%, IQR=3.0–29.2%) (p=0.04). In the 1990s, the APP was significantly higher in Asia (44.7%, IQR=38.0–59.0%) than in North America (15.9%, IQR=7.0–24.1%), and Oceania (13.1%, IQR=7.2–19.2%) (p<0.001). In the same decade, the APP was also significantly higher in Europe compared to North America (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in APP rates between regions in the 1980s and 2000s.

Figure 2.

Antipsychotic polypharmacy rate by decade and geographic region

■p=0.04; ▲Omnibus (p=0.03). Regions were significantly different after post-hoc test using a rank test corrected for multiple comparisons. ^Number of time points included in the analysis. Time point definition: some studies reported in a single article two or more APP rates, examined at different points in time (e.g. 1999 and 2000), constituting two or more different individual samples or “time points” in our database. Total Number of studies: 147. Total number of time points: 196. Studies were classified based on time of data collection and not publication date.

3.5. Variables associated with use of antipsychotic polypharmacy

Continuous variables that were associated with APP in bivariate analyses were percent of patients with schizophrenia (r=0.23, p=0.01), length of patient follow up (r=[−0.30], p=0.001), percent of FGA use (r=0.31, p<0.001), percent of LAI use (r=0.26, p=0.04), percent of concomitant antidepressant use (r=[−0.23], p=0.02), and percent of concomitant anticholinergic use(r=0.37, p<0.001). In the analysis of categorical variables, inpatient treatment (p<0.001), cross-sectional design (p=0.03), study origin in Asia (p=0.01), Europe (p=0.006), and countries other than North America (p<0.001) were associated with APP (Table 4.)

Table 4.

Categorical and continuous variables associated with Antipsychotic Polypharmacy

| Continuous variables | Time Points ^ |

r (Spearman’s Rho) | P -value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 124 | −0.09 | 0.31 | |

| % White | 33 | −0.23 | 0.20 | |

| % Male | 155 | 0.16 | 0.05 | |

| % Schizophrenia | 130 | 0.23 | 0.01 | |

| Patient f/u (months) | 117 | −0.30 | 0.001 | |

| Baseline CGI (severity) | 6 | 0.54 | 0.27 | |

| Total PANSS score | 5 | 0.10 | 0.87 | |

| Positive PANSS score | 4 | −0.60 | 0.40 | |

| Negative PANSS score | 4 | −0.80 | 0.20 | |

| Total BPRS score | 6 | 0.03 | 0.96 | |

| GAF score | 4 | 0.74 | 0.26 | |

| % FGA | 139 | 0.31 | <0.001 | |

| % SGA | 131 | 0.09 | 0.30 | |

| % Clozapine | 97 | 0.05 | 0.60 | |

| % Long-acting injectable preparations | 65 | 0.26 | 0.04 | |

| % Mood stabilizers | 40 | 0.19 | 0.23 | |

| % Lithium | 49 | −0.06 | 0.71 | |

| % Anticonvulsants | 40 | −0.13 | 0.44 | |

| % Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 94 | 0.11 | 0.29 | |

| % Antidepressants | 98 | −0.23 | 0.02 | |

| % Anticholinergics | 94 | 0.37 | <0.001 | |

| % Long-acting injectable preparations (APP sample) | 29 | 0.36 | 0.05 | |

| % FGA + FGA | 98 | 0.03 | 0.73 | |

| % SGA + SGA | 94 | −0.02 | 0.86 | |

| % FGA + SGA | 106 | 0.05 | 0.58 | |

| Categorical variables | 1st group | 2nd group | P- value+ | |

| From patient interview vs. other sources | 176 | 18.9(4.8–29.9) | 21.0(13.0–38.0) | 0.19 |

| Urban vs. mixed (urban and rural) | 125 | 22.0(13.0–38.0) | 18.5(9.5–29.5) | 0.34 |

| Academic institutions vs. others | 122 | 22.7(10.5–34.0) | 18.9(13.0–37.3) | 0.99 |

| Cross-sectional vs. longitudinal | 196 | 22.0(14.7–39.5) | 17.0(9.9–27.5) | 0.03 |

| Other vs. Inpatient | 175 | 17.0(9.8–24.1) | 27.5(16.1–46.0) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia <70% vs. >/= 70%* | 130 | 20.0(7.0–27.0) | 20.0(14.7–43.4) | 0.06 |

| Other decades vs. 1970–1979 | 196 | 19.1(13.0–34.5) | 28–8(7.5–44.4) | 0.47 |

| Other decades vs. 1980–1989 | 196 | 21.0(14.1–34.0) | 17.6(10.8–38.2) | 0.49 |

| Other decades vs. 1990–1999 | 196 | 19.0(13.0–34.0) | 22.0(11.0–40.0) | 0.63 |

| Other decades vs. 2000–2009 | 196 | 20.0(10.8–39.0) | 19.2(14.4–29.9) | 0.76 |

| <1996 vs. >/= 1996 | 196 | 19.0(10.8–40.0) | 19.8(14.1–34.0) | 0.90 |

| Other vs. North America | 196 | 23.0(15.0–42.1) | 16.0(7.2–24.4) | <0.001 |

| Other vs. Asia | 196 | 19.0(11.0–34.0) | 32.0(19.2–53.0) | 0.01 |

| Other vs. Europe | 196 | 17.1(9.1–28.3) | 23.0(15.0–42.1) | 0.006 |

| Other vs. Oceania | 196 | 20.0(13.0–37.3) | 16.4(9.8–20.0) | 0.09 |

| Clozapine <5% vs. >/= 5% * | 93 | 16.3(6.2–38.2) | 23.5(15.0–36.6) | 0.24 |

| Long-acting injectable <25% vs. >/=25%* | 65 | 22.0(15.2–35.0) | 35.7(18.5–46.0) | 0.04 |

| Mood stabilizers <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 40 | 20.9(11.9–23.9) | 22.0(15.9–29.5) | 0.46 |

| Lithium <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 48 | 18.9(10.5–37.8) | 16.9(11.9–35.0) | 0.77 |

| Anticonvulsants <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 40 | 28.5(16.2–51.5) | 25.6(14.4–41.7) | 0.52 |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 94 | 13.7(7.9–36.4) | 20.2(10.5–34.0) | 0.52 |

| Antidepressants <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 98 | 17.5(8.8–45.0) | 20.2(9.4–34.0) | 0.89 |

| Antidepressants <5% vs. >/= 5%* | 94 | 8.8(2.0–39.0) | 24.3(15.2–40.0) | 0.32 |

Continuous variables were dichotomized based on described values.

Number of time points: some studies reported in a single article two or more APP rates, examined at different points in time (e.g. 1999 and 2000), constituting two or more different individual samples in our database. Total Number of studies: 147. Total number of time points: 196. APP: antipsychotic polypharmacy; CGI: Clinical Global Impressions Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; FGA: First-Generation Antipsychotic. SGA: Second-Generation Antipsychotic.

Mann-Whitney test.

3.6. Stratified analyses

Prescribing practices differed between the low use LAI <25% group vs. the LAI ≥25% group. The latter had significantly higher rates of use of 2 antipsychotics (p=0.001), APP (p=0.04), FGAs (p=0.003), anticholinergics (p=0.004), FGA+FGA (p=0.03), and LAIs plus other antipsychotics (p=0.006). Conversely, the LAI <25% group had significantly higher rates of use of SGAs (p=0.03), mood stabilizers (p=0.03), anticonvulsants (p=0.007), SGA+SGA (p=0.02) and FGA+SGA (p=0.02) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Psychotropic medication prescribing practices after stratifying based on 25% use of long acting injectable

| Treatment Characteristics | LAI <25% | LAI >/=25% | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | |||

| 0 Antipsychotic, Median % (IQR)[^] | 4.2(0.0–19.0)[26] | 0.0(0.0–6.0)[26] | 0.10 |

| 1 Antipsychotic | 61.7(44.5–73.0)[26] | 56.1(42.0–76.0)[26] | 0.60 |

| 2 Antipsychotics | 14.1(8.4–23.6)[20] | 34.6(20.7–42.9)[20] | 0.001 |

| 3 or more Antipsychotics | 1.8(0.0–5.8)[20] | 4.8(0.0–11.8)[20] | 0.20 |

| APP (>/= 2 Antipsychotics)a | 22.0(15.2–35.0)[37] | 35.7(18.5–46.0)[28] | 0.04 |

| First-generation antipsychotics | 55.0(45.0–90.1)[34] | 90.5(74.0–100)[24] | 0.003 |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | 44.1(6.0–59.9)[26] | 1.1(0.0–24.0)[19] | 0.03 |

| Clozapine | 7.8(0.0–14.2)[26] | 0.0(0.0–9.5)[16] | 0.18 |

| Long-acting injectable preparations | 16.0(8.7–21.8)[37] | 47.1(30.5–66.2)[28] | <0.0001 |

| Comedications | |||

| Mood stabilizers b | 19.9(14.2–22.7)[10] | 6.5(4.0–11.1)[4] | 0.03 |

| Lithium b | 4.3(1.9–10.0)[14] | 4.7(3.0–7.2)[10] | 0.95 |

| Anticonvulsants b | 7.3(4.0–10.7)[10] | 1.0(0.0–5.7)[12] | 0.007 |

| Anxiolytics/hypnotics | 32.0(15.7–40.0)[25] | 33.1(15.0–39.0)[18] | 0.94 |

| Antidepressants | 14.1(7.8–24.7)[27] | 10.0(6.2–24.2)[17] | 0.45 |

| Anticholinergics | 35.1(26.9–46.8)[27] | 48.0(37.1–67.2)[17] | 0.004 |

| APP (>/= 2 Antipsychotics) | |||

| FGA + FGA | 52.0(0.0–100)[23] | 100(99.0–100)[15] | 0.03 |

| SGA + SGA | 1.5(0.0–15.6)[21] | 0.0(0.0–0.0)[15] | 0.02 |

| FGA + SGA | 26.5(0.0–56.5)[24] | 0.0(0.0–5.15)[16] | 0.02 |

| Long-acting injectable preparations | 11.4(0.0–31.8)[10] | 81.0(55.1–100)[16] | 0.006 |

Mann-Whitney test.

Number of time points. IQR: Interquantile range (percentile 25–75). APP: Antipsychotic Polypharmacy. FGA: First-Generation Antipsychotic. SGA: Second-Generation Antipsychotic.

The APP rate is not identical to the sum of patients taking 2 or >/=3 antipsychotics, as not all studies reporting on APP specified the exact number of antipsychotics prescribed;

Although overlapping conceptually, the terms “mood stabilizers”, “anticonvulsants” and “lithium” are taken directly from the publications.

Analysis by decades and regions in the higher and lower LAI groups were not meaningful due to small sample sizes. There were no significant differences in the APP rate between the clozapine <5% group (16.3%, IQR=6.2–38.2) and the clozapine ≥5% group (23.5, IQR=15.0–36.6) (p=0.24) (data not shown).

3.7. Sensitivity analysis by APP duration

Only few studies using a longitudinal definition of APP were available for which region and time matched studies with a cross-sectional definition could be identified (≥4 days: N=18 vs. 39; ≥28 days: N=13 vs. 38; ≥42 days: N=10 vs. 38; and ≥60 days: N=7 vs. 28). Across these groups of studies, APP rates did not differ for any of the definitions requiring increasing APP durations (p=0.42–0.68).

3.8. Meta-regression analysis

Given the impact of LAI use on APP rates, meta-regression analyses were stratified and examined in the <25% and ≥25% LAI use group. After testing all four proposed models, the same three variables were independently associated with APP in the LAI <25% group in each of the models: schizophrenia (p=0.004), inpatient treatment (p<0.0001) and FGA (p=0.046). These three variables accounted for 44% of the variance of APP (N=66; R2 =0.44, p<0.0001) in all four models. These variables were not significantly associated with APP in the high use LAI group (data not shown).

4. Discussion

This largest study of APP prevalence rates and correlates confirms that APP is quite common and that it has been present for the last four decades in all geographic regions (De las Cuevas et al., 2005; Gilmer et al., 2007; Hung and Cheung, 2008; Linjakumpu et al., 2002). Although substantial variations exist between and within geographic locations, a global median of 19.5% of patients received APP. In addition, our study suggests that in North America APP has increased by 34% since the 1980s, although likely due to variations across studies, this finding was not significant. A similar trend in APP, but with larger differences, was observed in Medicaid claims data bases, showing an increase from 5.7% in 1995 to 24.3% in 1999 (Clark et al., 2002) and from 32% in 1998 to 41% in 2000 (Ganguly et al., 2004). Furthermore, a similar, but non-significant pattern was noted in Oceania, where APP increased from 2% to 17.7% over the past 3 decades with data. These increased trends could be partially explained by a wider availability of SGAs, which increase treatment options and may cause less extrapyramidal side effects when combined with other antipsychotics, potentially fostered by a more liberal health care system, particularly in North America. Moreover, the introduction of SGAs could have led to an increase in APP as more antipsychotic switches were attempted with a greater potential to not being completed, in addition to a general tendency to higher expectations regarding treatment outcomes in the recent decade. Furthermore, the more varied pharmacodynamic profiles of SGAs compared to FGAs on the one hand, and their less pronounced dopamine affinity compared to high-potency FGAs on the other hand, might have stimulated the belief that combining antipsychotics with more different profiles might yield better outcomes and be more justifiable, suggested by the highest cotreatment rate of SGAs+FGAs.

Conversely, the overall APP rates decreased in Asia over the last two decades and slightly decreased in Europe over the last decade. Reasons for these trends are unclear. While the introduction of SGAs could have led to a decrease in APP by replacing FGA APP with SGA monotherapy, because of expected or real improved efficacy, recent studies have refuted the earlier claims that SGAs had in general better efficacy than FGAs (Jones et al., 2006; Leucht et al., 2009; Lieberman et al., 2005), except for clozapine.

As shown before (Bitter et al., 2003; Chong et al., 2000a), APP rates in Asia and Europe have consistently been higher compared to North America and Oceania for the last four decades, although in our study, these differences only reached statistical significance in 1990s. Although reasons for higher APP rates in Asia are not entirely clear, this may be partially related to the belief in Oriental traditional medicine that a mixture of different medicinal compounds is superior to single compounds (Chong et al., 2000a). Our finding that Europe had higher APP rates than North America was previously shown by Bitter and colleagues (Bitter et al., 2003), finding higher rates of APP in Hungary (32.7% in first sample and 52% in another sample) compared to New York (16.9%). Reasons for a higher APP rate in Europe than North America are unclear, but could be due to the significantly higher use of LAI preparations in Europe or use of add-on low potency FGAs instead of adjunctive benzodiazepines. In Oceania, APP rates were generally lower than in other regions, which may be related to higher clozapine utilization. Nevertheless, despite cultural differences, APP rates generally converged over time across regions.

Regarding antipsychotic class combinations, FGAs were preferred as part of APP in Europe and Asia, while SGAs were used the most in North America and Oceania. Given the cost of antipsychotics, it is not surprising that regions with a more “socialized” and cost conscious health care systems, like Asia and Europe, used FGAs preferentially, while countries like the US favored using SGAs.

Expectedly, the regional frequency of anticholinergic use paralleled that of APP. In fact, higher anticholinergic use has been associated with APP consistently (Carnahan et al., 2006; Centorrino et al., 2004). Anxiolytic and Hypnotic use was higher in Europe, which was associated with a higher use of FGAs, but not of anticholinergics, possibly because lower-potency antipsychotics are used that have less EPS potential (Leucht et al., 2003) or because benzodiazepines can reduce EPS (Lima et al., 2002).

The utilization of mood stabilizers and, specifically of anticonvulsants, was particularly higher in North America compared to Europe and Asia. Multiple factors could underlie these variations, including the use of different medications to address similar symptoms and side effects in different regions. Whereas Asian clinicians may use another antipsychotic to treat residual/acute symptoms, European clinicians may use benzodiazepines or low potency FGA, while North American clinicians tend to use more mood stabilizers to treat aggression and hostility (Volavka and Citrome 2008).

Strikingly, Asian clinicians did not use antidepressants as much as clinicians in all other regions, and the rate of antidepressant use was highest in Oceania where the APP rate was lower compared to Asia and Europe. This low use of antidepressants in Asia could also be explained by their potential use of a second antipsychotic to target depression, but under-recognition of depression in schizophrenia patients could also be a factor. However, the relationship between antidepressant and APP use requires further clarification.

Unfortunately, very few studies of APP reported psychopathology ratings or adverse effects, highlighting another under-researched area.

Consistent with prior reports (Biancosino et al., 2005; Brunot et al., 2002; Castberg and Spigset, 2008; Fourrier et al., 2000; Kreyenbuhl et al., 2007b; Lelliott et al., 2002; Millier et al., 2011; Morrato et al., 2007; Stroup et al., 2009; Tibaldi et al., 1997), APP was associated with variables that indicate patients had higher illness severity and, possibly refractoriness (Barbui et al., 2006b; Tomasi et al., 2006), including schizophrenia diagnosis, inpatient status, greater LAI use and shorter follow-up. Moreover, the fact that cross-sectional studies and those with shorter follow-up tended to have higher APP rates, suggests that at least some of the APP was either part of cross-titration or transient. The higher use of anticholinergics, found in multiple studies of APP (Chakos et al., 2006; Florez Menendez et al., 2004; Ganguly et al., 2004; Hong and Bishop, 2010; Kreyenbuhl et al., 2007b; Procyshyn et al., 2001; Sim et al., 2004), indicates that clinicians run the risk of inducing clinically relevant EPS in patients treated with APP. The association of peripherally measured anticholinergic medication load with impaired learning during cognitive remediation (Vinogradov et al., 2009) calls into question the benefits of treating patients with APP above the EPS threshold, followed by anticholinergic use. While the inverse correlation between antidepressant use and APP is interesting, it is currently unclear if there is any causal association. Nevertheless, prior studies have related APP to greater rates of depression (Kreyenbuhl et al., 2007a) and negative symptoms (Morrato et al., 2007). Thus antidepressant use may manage these symptom clusters that otherwise increase APP in a subgroup of patients. In contrast, in our meta-regression, only inpatient status, use of FGAs and schizophrenia diagnosis independently predicted APP. This discrepancy to the bivariate correlational analyses may have been a power issue, as information on these variables was not uniformly available across studies, highlighting the need for additional studies.

The results of our study need to be interpreted within its limitations, including the fact that many studies did not focus on APP or reported with too little specificity, reducing the amount of data for the meta-regression. Additionally, studies had heterogeneous design and population characteristics, and were conducted at different times across different health care systems and treatment cultures. Furthermore, differences pertaining to when and in whom LAIs are being prescribed make LAI use an imperfect proxy for illness chronicity. Moreover, there may be geographic differences in reimbursement structures that impact on APP rates or discourage high dose antipsychotic monotherapy, encouraging APP as a means of increasing dopamine blockade. Also, 86.4% of the studies used a cross-sectional APP definition, which does not allow us to accurately discriminate between cross-titration and relatively persistent polypharmacy. However, in our sensitivity analysis, we did not find significant differences between the APP rates of studies that used a cross-sectional definition or varying longitudinal definitions of APP. Nevertheless, only few studies required a defined duration of antipsychotic cotreatment. Therefore, future studies should provide rates for definitions of APP that require varying durations of antipsychotic overlap (e.g., ≥30, ≥60 and ≥90 days). Finally, APP rates were heterogeneous between and within geographic locations, so that one cannot generalize mean or median rates to a given practice location, country or continent.

In summary, this study shows that APP has been used for decades and across multiple regions, and disorders, being most common in patients with schizophrenia. APP seems to be prescribed for more severely ill and possibly more refractory patients, seemingly in lieu of clozapine use, and APP involving FGAs is associated with clinically relevant EPS requiring additional anticholinergic use. A better understanding of clinicians’ rationale for using APP (Correll et al., 2011) and of the efficacy, tolerability (Gallego et al. in press) and effectiveness of this strategy is needed to guide clinicians and to inform the development of more evidence based treatment guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Catalina Niño, MD, for her help with entering data and formatting the tables.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported in parts by The Zucker Hillside Hospital-National Institute of Mental Health (Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research for the Study of Schizophrenia MH 074543-01 to J.M.K.) and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine CTSA Grant UL1 RR025750 and KL2 RR025749 and TL1 RR025748 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. The NIMH and NCRR had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Actelion, Alexza; AstraZeneca, Biotis, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Desitin, Eli Lilly, GSK, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medicure, Medscape, Merck, Novartis, Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Schering-Plough, Sepracor/Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda and Vanda. He has received grant support from BMS, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Janssen/J&J, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) and Otsuka.

Dr. Kane has been a consultant to or has received honoraria from Alkermes, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo, Eli Lilly, Intra-Cellular Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, NuPathe, Otsuka, Pierre Fabrehe, Pfizer Inc, PgXHealth, Proteus, Schering, Shire, Solvay, Takeda, Vanda and Wyeth. He has served on the speaker’s bureau of AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Janssen and Merck and he is a share holder of MedAvante.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: Part of the data were presented in poster format at the NCDEU meeting, Hollywood, FL, June 2009.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr.Gallego, Dr. Zhang and Dr. Bonetti have nothing to disclose.

Contributors

Dr. Gallego conducted the literature search, extracted the data, conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Dr. Bonetti helped with literature search and data extraction and helped in editing the content of the manuscript. Dr. Zhang helped with data extraction, conducted the meta-regression analysis and helped editing the content of the manuscript. Dr. Kane helped reviewing the content of the manuscript. Dr. Correll designed the study, helped with data extraction and literature search, and helped editing the content of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Advokat C, Dixon D, Schneider J, Comaty JE., Jr Comparison of risperidone and olanzapine as used under "real-world" conditions in a state psychiatric hospital. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J, McCombs JS, Jung C, Croudace TJ, McDonnell D, Ascher-Svanum H, Edgell ET, Shi L. Classifying patients by antipsychotic adherence patterns using latent class analysis: characteristics of nonadherent groups in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Value Health. 2008;11(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambuhl B, Wurmle O, Michel K. Prescribing practice of psychotropic drugs in a psychiatric university clinic. Psychiatr Prax. 1993;20(2):70–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananth J, Parameswaran S, Gunatilake S. Antipsychotic polypharmacy. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(18):2231–2238. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SE, Johansson M, Manniche C. The prescribing pattern of a new antipsychotic: a descriptive study of aripiprazole for psychiatric in-patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103(1):75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DN. A comparison of in-patient and out-patient prescribing. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:644–649. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ, Kando JC, Centorrino F. Hospital use of antipsychotic agents in 1989 and 1993: stable dosing with decreased length of stay. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1038–1044. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini A, Boccalon RM, Boncompagni G, Casacchia M, Margari F, Minervini L, Righi R, Russo F, Salteri A, Frediani S, Rossi A, Scatigna M. Clinical features and therapeutic management of patients admitted to Italian acute hospital psychiatric units: the PERSEO (psychiatric emergency study and epidemiology) survey. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui C, Nose M, Mazzi MA, Bindman J, Leese M, Schene A, Becker T, Angermeyer MC, Koeter M, Gray R, Tansella M. Determinants of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drug use in clinically unstable patients with schizophrenia treated in four European countries. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006a;21(2):73–79. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000185022.48279.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui C, Nose M, Mazzi MA, Thornicroft G, Schene A, Becker T, Bindman J, Leese M, Helm H, Koeter M, Weinmann S, Tansella M. Persistence with polypharmacy and excessive dosing in patients with schizophrenia treated in four European countries. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006b;21(6):355–362. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000224785.68040.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbui C, Signoretti A, Mule S, Boso M, Cipriani A. Does the addition of a second antipsychotic drug improve clozapine treatment? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):458–468. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancosino B, Barbui C, Marmai L, Dona S, Grassi L. Determinants of antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychiatric inpatients: a prospective study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(6):305–309. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingefors K, Isacson D, Lindstrom E. Dosage patterns of antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia in Swedish ambulatory clinical practice--a highly individualized therapy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(4):263–269. doi: 10.1080/08039480307280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter I, Chou JC, Ungvari GS, Tang WK, Xiang Z, Iwanami A, Gaszner P. Prescribing for inpatients with schizophrenia: an international multi-center comparative study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(4):143–149. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botts S, Hines H, Littrell R. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the ambulatory care setting, 1993–2000. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1086. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayley J, Rafalowicz E, Yellowlees P. Psychotropic drug prescribing in a general hospital inpatient psychiatric unit. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;23(3):352–356. doi: 10.3109/00048678909068292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekema WJ, de Groot IW, van Harten PN. Simultaneous prescribing of atypical antipsychotics, conventional antipsychotics and anticholinergics-a European study. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(3):126–130. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9063-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunot A, Lachaux B, Sontag H, Casadebaig F, Philippe A, Rouillon F, Clery-Melin P, Hergueta T, Llorca PM, Moreaudefarges T, Guillon P, Lebrun T. Pharmacoepidemiological study on antipsychotic drug prescription in French Psychiatry: Patient characteristics, antipsychotic treatment, and care management for schizophrenia. Encephale. 2002;28(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley P, Miller A, Olsen J, Garver D, Miller DD, Csernansky J. When symptoms persist: clozapine augmentation strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(4):615–628. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, Chrischilles EA. Increased risk of extrapyramidal side-effect treatment associated with atypical antipsychotic polytherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(2):135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castberg I, Spigset O. Prescribing Patterns and the Use of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Psychotropic Medication in a Psychiatric High-Security Unit. Ther Drug Monit. 2008 doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31818622c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle D, Morgan V, Jablensky A. Antipsychotic use in Australia: the patients' perspective. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(5):633–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan J, Gath DH, Bond A, Edmonds G, Martin P, Ennis J. General practice patients on long-term psychotropic drugs. A controlled investigation. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152(3):399–405. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centorrino F, Cincotta SL, Talamo A, Fogarty KV, Guzzetta F, Saadeh MG, Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ. Hospital use of antipsychotic drugs: polytherapy. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centorrino F, Goren JL, Hennen J, Salvatore P, Kelleher JP, Baldessarini RJ. Multiple versus single antipsychotic agents for hospitalized psychiatric patients: case-control study of risks versus benefits. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):700–706. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centorrino F, Eakin M, Bahk WM, Kelleher JP, Goren J, Salvatore P, Egli S, Baldessarini RJ. Inpatient antipsychotic drug use in 1998, 1993, and 1989. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1932–1935. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakos MH, Glick ID, Miller AL, Hamner MB, Miller DD, Patel JK, Tapp A, Keefe RS, Rosenheck RA. Baseline use of concomitant psychotropic medications to treat schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1094–1101. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu HFK, Shum PS, Lam CW. Psychotropic drug prescribing to chronic schizophrenics in a Hong Kong hospital. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1991;37(3):187. doi: 10.1177/002076409103700305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong MY, Tan CH, Fujii S, Yang SY, Ungvari GS, Si T, Chung EK, Sim K, Tsang HY, Shinfuku N. Antipsychotic drug prescription for schizophrenia in East Asia: rationale for change. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(1):61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Ravichandran N, Poon LY, Soo KL, Verma S. Reducing polypharmacy through the introduction of a treatment algorithm: use of a treatment algorithm on the impact on polypharmacy. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(7):457–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Remington GJ, Lee N, Mahendran R. Contrasting clozapine prescribing patterns in the east and west? Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000a;29(1):75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Sachdev P, Mahendran R, Chua HC. Neuroleptic and anticholinergic drug use in Chinese patients with schizophrenia resident in a state psychiatric hospital in Singapore. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000b;34(6):988–991. doi: 10.1080/000486700274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong SA, Remington GJ, Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ. Effect of clozapine on polypharmacy. Psychiatr Serv. 2000c Feb;51(2):250–252. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Holden N. The persistence of prescribing habits: a survey and follow-up of prescribing to chronic hospital in-patients. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 1987;150:88. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Bartels SJ, Mellman TA, Peacock WJ. Recent trends in antipsychotic combination therapy of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: implications for state mental health policy. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):75–84. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly A, Taylor D. Ethnicity and quality of antipsychotic prescribing among in-patients in south London. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(2):161–162. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly A, Rogers P, Taylor D. Antipsychotic prescribing quality and ethnicity: a study of hospitalized patients in south east London. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(2):191–197. doi: 10.1177/0269881107065899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, Kane JM, Leucht S. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443–457. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Shaikh L, Gallego JA, Nachbar J, Olshanskiy V, Kishimoto T, Kane JM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: a survey study of prescriber attitudes, knowledge and behavior. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1–3):58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell NH, Jackson CT, Evans AC, Essock SM. Antipsychotic prescribing practices in Connecticut's public mental health system: rates of changing medications and prescribing styles. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):17–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divac N, Jasovic-Gasic M, Samardzic R, Lackovic M, Prostran M. Antipsychotic polypharmacy at the University Psychiatric Hospital in Serbia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(11):1250–1251. doi: 10.1002/pds.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlinger M, Hausmann A, Kemmler G, Kurz M, Kurzthaler I, Walch T, Walpoth M, Fleischhacker WW. Trends in the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia over a 12 year observation period. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Kumar V. A survey of prescribing of psychotropic drugs in a Birmingham psychiatric hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145:502–507. doi: 10.1192/bjp.145.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elie D, Poirier M, Chianetta J, Durand M, Gregoire C, Grignon S. Cognitive effects of antipsychotic dosage and polypharmacy: a study with the BACS in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0269881108100777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ereshefsky L. Pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic considerations in choosing an antipsychotic. Physicians Postgraduate Press; 1999. pp. 20–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essock SM, Schooler NR, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Rojas I, Jackson C, Covell NH. Effectiveness of switching from antipsychotic polypharmacy to monotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):702–708. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10060908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faries D, Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Correll C, Kane J. Antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy in the naturalistic treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez Menendez G, Blanco Ramos M, Gomez-Reino Rodriguez I, Gayoso Diz P, Bobes Garcia J. Polypharmacy in the antipsychotic prescribing in practices psychiatric out-patient clinic. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2004;32(6):333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Mousson F, Dassonville B, Bost PS, Jaeger M, Roques N, Swain G. A study of prescriptions for psychotropic drugs at a French psychiatric hospital. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1989;37(1):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourrier A, Gasquet I, Allicar MP, Bouhassira M, Lepine JP, Begaud B. Patterns of neuroleptic drug prescription: a national cross-sectional survey of a random sample of French psychiatrists. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):80–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangou S, Lewis M. Atypical antipsychotics in ordinary clinical practice: a pharmacoepidemiologic survey in a south London service. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15(3):220–226. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galletly CA, Tsourtos G. Antipsychotic drug doses and adjunctive drugs in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997;9(2):77–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1026249101457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego JA, Nielsen J, DeHert M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert Review on Drug Safety. 2012 May 8; doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.683523. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID 22563628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S, Taylor R, Rabheru K, Forbes I, Dumontet J, Procyshyn RM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy does not increase the risk for side effects. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):323–324. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, Kennedy K, Martin BC. Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy among Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998–2000. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1377–1388. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Folsom DP, Mastin W, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic polypharmacy trends among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia in San Diego County, 1999–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(7):1007–1010. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann R, Engel RR, Geissler KH, Ruther E. Psychotropic drug use in psychiatric inpatients: recent trends and changes over time-data from the AMSP study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(Suppl 1):S27–S38. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann J, Ruppert A, Auby P, Pugner K, Kissling W. Antipsychotic prescribing patterns in Germany: a retrospective analysis using a large outpatient prescription database. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(4):237–242. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssens L, De Hert M, Wampers M, Reginster JY, Peuskens J. Pharmacological treatment of ambulatory schizophrenic patients in Belgium. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2006;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington M, Lelliott P, Paton C, Okocha C, Duffett R, Sensky T. The results of a multi-centre audit of the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs for in-patients in the UK. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2002;26(11):414. [Google Scholar]

- Heresco-Levy U, Greenberg D, Wittman L, Dasberg H, Lerer B. Prescribing patterns of neuroactive drugs in 98 schizophrenic patients. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1989;26(3):157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hida H, Faber M, Alberto-Gondouin M, Jalaguier E. Analyse des prescriptions de psychotropes dans un Centre Hospitalier Psychiatrique= A survey of psychotropic drugs prescribing in a psychiatric hospital. ThÈrapie. 1997;52(6):573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway F. Prescribing for the long-term mentally ill. A study of treatment practices. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152(4):511. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RJ, Gaskins JD. Neuroleptic drug use in a family-practice center. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1981;38(11):1716–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong IS, Bishop JR. Anticholinergic use in children and adolescents after initiation of antipsychotic therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(7–8):1171–1180. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H, Noguchi H, Hashimoto R, Nakabayashi T, Omori M, Takahashi S, Tsukue R, Anami K, Hirabayashi N, Harada S, Saitoh O, Iwase M, Kajimoto O, Takeda M, Okabe S, Kunugi H. Antipsychotic medication and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1–3):138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humberstone V, Wheeler A, Lambert T. An audit of outpatient antipsychotic usage in the three health sectors of Auckland, New Zealand. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(4):240–245. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung GB, Cheung HK. Predictors of high-dose antipsychotic prescription in psychiatric patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14(1):35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Koyama A, Higuchi T. Polypharmacy and excessive dosing: psychiatrists' perceptions of antipsychotic drug prescription. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:243–247. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Levine J. Antipsychotic medication coprescribing in a large state hospital system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(1):41–48. doi: 10.1002/pds.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen B, Weinmann S, Berger M, Gaebel W. Validation of polypharmacy process measures in inpatient schizophrenia care. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):1023–1033. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrell JM, McIntyre RS. Adverse events in children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic medications. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(4):283–290. doi: 10.1002/hup.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Wright NF. Drug prescribing for schizophrenic out-patients on depot injections. Repeat surveys over 18 years. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:827–834. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PB, Barnes TR, Davies L, Dunn G, Lloyd H, Hayhurst KP, Murray RM, Markwick A, Lewis SW. Randomized controlled trial of the effect on Quality of Life of second- vs first-generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1079–1087. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukamaa M, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Raitasalo R, Lehtinen V. Schizophrenia, neuroleptic medication and mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:122–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keks NA, Altson K, Hope J, Krapivensky N, Culhane C, Tanaghow A, Doherty P, Bootle A. Use of antipsychosis and adjunctive medications by an inner urban community psychiatric service. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33(6):896–901. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiivet RA, Llerena A, Dahl ML, Rootslane L, Sanchez Vega J, Eklundh T, Sjoqvist F. Patterns of drug treatment of schizophrenic patients in Estonia, Spain and Sweden. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40(5):467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogut SJ, Yam F, Dufresne R. Prescribing of antipsychotic medication in a medicaid population: use of polytherapy and off-label dosages. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(1):17–24. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl J, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, Blow FC. Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl J, Marcus SC, West JC, Wilk J, Olfson M. Adding or switching antipsychotic medications in treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2007a;58(7):983–990. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.7.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl JA, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, Blow FC. Long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy in the VA health system: patient characteristics and treatment patterns. Psychiatr Serv. 2007b;58(4):489–495. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey SL, Gray SL, Sales AE, Sullivan J, Hedrick SC. Psychotropic use in community residential care facilities: A prospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(3):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass J, Mannik A, Bell JS. Pharmacotherapy of first episode psychosis in Estonia: comparison with national and international treatment guidelines. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33(2):165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc G, Cormier HJ, Vaillancourt S, Gagne MA, Gingras C. Who are the patients treated in an outpatient clinic with high dosage neuroleptics? Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35(1):12–24. doi: 10.1177/070674379003500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Walker V. Polypharmacy as the initial second-generation antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):717. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelliott P, Paton C, Harrington M, Konsolaki M, Sensky T, Okocha C. The influence of patient variables on polypharmacy and combined high dose of antipsychotic drugs prescribed for in-patients. RCP. 2002:411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Leppig M, Bosch B, Naber D, Hippius H. Clozapine in the treatment of 121 out-patients. Psychopharmacology. 1989;99:77–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00442565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerma-Carrillo I, de Pablo Bruhlmann S, del Pozo ML, Pascual-Pinazo F, Molina JD, Baca-Garcia E. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in patients with schizophrenia in a brief hospitalization unit. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2008;31(6):319–332. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31815cba78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA. Use of pharmacy data to assess quality of pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia in a national health care system: individual and facility predictors. Med Care. 2001;39(9):923–933. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima AR, Soares-Weiser K, Bacaltchuk J, Barnes TR. Benzodiazepines for neuroleptic-induced acute akathisia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(1) 2002 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001950. CD001950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M, Scheel T, Xaver Eich F. Dosage finding and outcome in the treatment of schizophrenic inpatients with amisulpride. Results of a drug utilization observation study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(2):111–119. doi: 10.1002/hup.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, Koponen H, Kivela SL, Isoaho R. Psychotropics among the home-dwelling elderly--increasing trends. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(9):874–883. doi: 10.1002/gps.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Vol. 49. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. Practical Meta Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Loosbrock DL, Zhao Z, Johnstone BM, Morris LS. Antipsychotic medication use patterns and associated costs of care for individuals with schizophrenia. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003;6(2):67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Guarneri M, Marasco C, De Rosa C, Malangone C, Maj M National Mental Health Project Working, G. Prescription of psychotropic drugs to patients with schizophrenia: an Italian national survey. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60(7):513–522. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0803-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason AS, Nerviano V, DeBurger RA. Patterns of antipsychotic drug use in four Southeastern state hospitals. Dis Nerv Syst. 1977;38(7):541–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue RE, Waheed R, Urcuyo L. Polypharmacy in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):984–989. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath AM, Jackson GA. Survey of neuroleptic prescribing in residents of nursing homes in Glasgow. BMJ. 1996;312(7031):611–612. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events associated with antipsychotic treatment in children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):929–935. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.10.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megna JL, Kunwar AR, Mahlotra K, Sauro MD, Devitt PJ, Rashid A. A study of polypharmacy with second generation antipsychotics in patients with severe and persistent mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13(2):129–137. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000265773.03756.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer T, Tiltscher C, Schmauss M. [Polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2006;74(7):377–391. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-915576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel K, Kolakowska T. A survey of prescribing psychotropic drugs in two psychiatric hospitals. Br J Psychiatry. 1981;138:217–221. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millier A, Sarlon E, Azorin JM, Boyer L, Aballea S, Auquier P, Toumi M. Relapse according to antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenic patients: a propensity-adjusted analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JD, Lerma-Carrillo I, Leonor M, Pascual F, Blasco-Fontecilla H, Gonzalez-Parra S, Lopez-Munoz F, Alamo C. Combined treatment with amisulpride in patients with schizophrenia discharged from a short-term hospitalization unit: a 1-year retrospective study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(1):10–15. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0B013E3181672213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, Gopalaswamy AK. Psychotropic drugs: another survey of prescribing patterns. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:298–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrato EH, Dodd S, Oderda G, Haxby DG, Allen R, Valuck RJ. Prevalence, utilization patterns, and predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy: experience in a multistate Medicaid population, 1998–2003. Clin Ther. 2007;29(1):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muijen M, Silverstone T. A comparative hospital survey of psychotropic drug prescribing. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:501–504. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscettola G, Casiello M, Bolline P, Sebastiani G, Pampallona S, Tognoni G. Pattern of therapeutic intervention and role of psychiatric settings: a survey in two regions of Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;75(1):55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naber D, Holzbach R, Perro C, Hippius H. Clinical management of clozapine patients in relation to efficacy and side-effects. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;(Suppl)(17):54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandurangi AK, Dalkilic A. Polypharmacy with second-generation antipsychotics: a review of evidence. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14(6):345–367. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000341890.05383.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton C, Lelliott P, Harrington M, Okocha C, Sensky T, Duffett R. Patterns of antipsychotic and anticholinergic prescribing for hospital inpatients. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(2):223–229. doi: 10.1177/0269881103017002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock L, Gerlach J. Clozapine treatment in Denmark: concomitant psychotropic medication and hematologic monitoring in a system with liberal usage practices. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(2):44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Lu SH, Wang RW. Economic reforms and the acute inpatient care of patients with schizophrenia: the Chinese experience. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1228–1234. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povlsen U, Norrng U, Fog R, Gerlach J. Tolerability and therapeutic effect of clozapine. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1985;71(2):176–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]