SUMMARY

Nerve sheath tumours arising from the sympathetic chain are extremely rare and are a diagnostic challenge. We report the case of a 31- year-old man who presented with an asymptomatic right cervical swelling. He was evaluated with sonography, CT, MR and angiography. Surgical excision of the lesion was performed, and histological examination revealed a schwannoma. The differential diagnosis of such tumours and their management are discussed.

KEY WORDS: Sympathetic chain, Schwannoma

RIASSUNTO

I tumori che originano dalle guaine mieliniche della catena del simpatico sono estremamente rari e rappresentano una sfida diagnostica. Riportiamo il caso di un uomo di 31 anni che si è presentato alla nostra osservazione con una tumefazione laterocervicale destra asintomatica. Dopo una accurata valutazione con ecotomografia, TC, RM ed angiografia, la lesione è stata asportata chirurgicamente e l'esame istologico ha dato il risultato di schwannoma. Vengono discussi diagnosi differenziale e trattamento di tali tipi di neoplasie.

Introduction

Schwannomas, neurilemmomas or neurinomas are benign nerve sheath tumours deriving from Schwann cells that occur in the head and neck region in 25-45% of cases 1. Cervical lesions originate from spinal nerves, the last four cranial nerve roots, or occasionally from the sympathetic chain 2. Microscopically, schwannomas are encapsulated, solid or cystic tumours. They can be composed of two cellular zones: Antony type A, densely arranged with spindle-shaped Schwann cells and areas of palisading nuclei, and Antony B, characterized by a hypocellular arrangement and a large quantity of myxoid tissue 3. Cervical schwannomas are uncommon, but those arising from the cervical sympathetic chain are extremely rare, with less than 60 cases reported in the English literature 2 4. In this report, we document a case manifesting as a swelling in the upper neck, which confirms the typical presentation of the tumour, displacing the carotid arteries anteriorly 5. Difficulties in diagnosis and treatment are discussed.

Case report

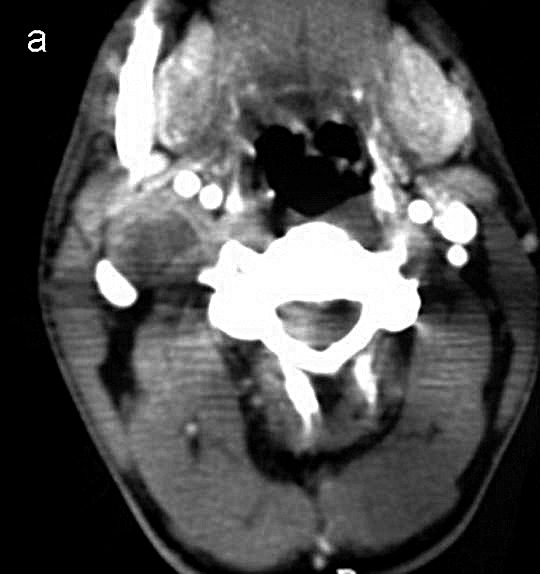

A 31-year-old man, with an asymptomatic swelling in the right upper lateral neck, came to our attention in December 2008. There was no history of hoarseness, nasal regurgitation, syncopal attacks, associated pain, fever or trauma. Examination revealed a firm, 3 × 2 cm retromandibular swelling that was not mobile in longitudinal or transverse planes. Oropharynx examination revealed no displacement of the peritonsillar structures, and indirect laryngoscopy excluded vocal cord paralysis. Ultrasonography showed a 3 × 2 cm mass displacing the carotid arteries slightly forward. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the neck (Fig. 1a) revealed a well-defined contrast-enhanced, oval 24 mm lesion in the retro-styloid compartment of the right parapharyngeal space. The mass, located behind the angle of the mandible, displaced the internal and external carotid arteries anteriorly, and did not compress the internal jugular vein.

Fig. 1a.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT section at the level of the angle of the mandible shows an oval-shaped, well-defined, hypodense 24 mm lesion in the retro-styloid compartment of the right parapharyngeal space.

MR sagittal T1-weighted images confirmed a low intensity mass in the upper right neck, posterior to the ascendant ramus of the mandible with heterogeneous enhancement after contrast medium administration. Coronal T2-weighted images (Fig. 1b) defined the supero-inferior extent of the lesion. Angiography of the right major vessels (Fig. 1c) revealed a thin pathologic circle with an oval image just above the carotid bifurcation; there was no hypervascularization or splaying of the internal and external carotid arteries. Thus, a carotid body tumour could be excluded.

Fig. 1b.

Coronal MRI T2- weighted image reveals a mass in the right parapharyngeal space and defines the superoinferior extent of this high intensity lesion.

Fig. 1c.

Digital subtraction angiography of the right major vessels reveals a thin pathologic circle with an oval image posterior to the carotid bifurcation, without splaying of the internal and external carotid arteries.

In doubt of a primitive or secondary lymph node pathology, FNAB was proposed but not performed because of patient refusal. The patient underwent surgical treatment with a provisional diagnosis of lymphadenopathy or a neural tumour. The lymphatic nature of the lesion was thought to be less probable because of the retro-styloid location of the mass and the absence of general signs of a lymphatic pathology. Preoperative diagnosis of a neural tumour was not possible as there were no significant signs for vagus (hoarseness and vocal cord palsy) or sympathetic chain involvement (Horner's syndrome). No radiological connection of the tumour with vagal trunk, spinal roots or sympathetic chain, or a superficial position of the vagus over the mass was observed, but this latter sign has been reported only in some large sympathetic cervical tumours 6.

The neck was explored by a transverse right submandibolar skin incision. Deep to the upper portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, an encapsulated, white coloured, 3 × 2 cm tumour was found between the internal and external carotid artery anteromedially, and the internal jugular vein posterolaterally. Vascular structures were not stretched or compressed. The tumour appeared to originate from the sympathetic chain. The eccentric site of the mass and the presence of a capsule indicated that it was probably a benign lesion. The mass was carefully dissected from the nerve while trying to avoid any damage to it. As it was not possible to dissect the tumour without damage to the nerve bundles, the capsule was incised longitudinally so that the tumour could be excised from inside. Nevertheless, a partial right side Horner's syndrome occurred, with mild ophthalmologic signs but without facial anydrosis, as reported in some cases 7.

Histopathological examination of the specimen confirmed the tumour to be a benign schwannoma originating from the sympathetic chain. Postoperatively, the complication was well tolerated and required no treatment.

Discussion

Cervical sympathetic chain schwannomas (CSCS) are rare, benign tumours originating from the superior or middle part of the cervical chain 2 and typically located in the retrostyloid compartment of the parapharyngeal space. CSCS occur more frequently in adults 20 to 50 years old, but are even observed in patients aged 5 to 77, without sex preference 4. Schwannoma of the vagus nerve grows between the internal or common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein causing separation of the two vascular structures; no separation has been seen between the artery and the vein in CSCS. A large tumour 6 8 9 can displace the internal carotid artery and vagus nerve antero-laterally 10 or the internal carotid artery also in addition to the internal jugular vein 11.

Most CSCS appear as asymptomatic and solitary masses in the mid or upper lateral neck that tend to grow slowly, approximately 3 mm per year 12, thus avoiding compression of other structures until advanced stages. Rarely, they arise near the vertebral foramina presenting with intraspinal and extraspinal components 13. The size reported in the literature for CSCS has been between 2 and 7.5 cm in major diameter 4. These tumours grow at least to 2.5-3 cm before they are detected 10. Horner's syndrome is rarely apparent on physical examination with only 6 cases reported 5. Pulsation is an atypical finding for CSCS and may be due to reflection of the carotid artery system, or it may be true pulsation caused by schwannoma hypervascularity 6 8 13 14. Neck pain, neurological defects and compression symptoms should suggest malignancy from neurogenic sarcomas, neuroepitheliomas and malignant melanomas 2 15, since malignant transformation of schwannomas is thought to occur infrequently 16 17.

In recent years CT has been used widely to localize parapharyngeal lesions, distinguishing pre-styloid from poststyloid ones 4. A mass on contrast-CT pushing the internal carotid artery or common carotid artery anteriorly is suggestive of schwannoma originating from the sympathetic chain or vagus nerve 10. On MR-imaging, a schwannoma is generally hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, depending on its cellularity. The random distribution of Antoni A and B within the tumour is responsible for the dishomogeneous signal at MRI 18. There is marked enhancement of the solid component of the tumour following the administration of gadolinium.

Conventional digital subtraction angiography (DSA), though invasive, is performed to reveal vascularity within the tumour or around the capsule 8-19. Schwannomas can appear as hypovascular or moderately hypervascular tumours on angiography 13, and the hypervascular type may display tortuous vessels and reveal puddling of contrast material, but no arteriovenous shunting or luminal narrowing 20. In our case, DSA showed a thin oval pathologic circle anterior to the carotid bifurcation, adequate for moderate vascularization. There was no hypervascularity or splaying of the internal or external carotid arteries, typical in carotid body tumour (CBT). Incisional biopsy can lead to a correct diagnosis in most cervical masses, but unfortunately it presents some risk of complications such as a nerve lesion, uncontrolled haemorrhage or a successive more difficult resection. FNAB provides far less valuable information for the compact neural tumours 4, and FNA-cytology can lead to correct diagnosis in only 25% of cervical schwannomas.

The main differential diagnosis in the suspect of CSCS is to distinguish it from other pathologies of the retrostyloid parapharyngeal space such as neurogenic tumours involving cranial nerves IX through XII and paragangliomas arising from the vagus nerve or carotid body 10. Deep lobe parotid tumours, lipomas and benign and malignant lymphadenopathies can be excluded as they arise in the pre-styloid compartment.

CBT must be considered, especially if the tumour presents as a pulsatile mass. A "salt and pepper" pattern on postgadolinium MRI sequences is commonly seen in CBT, but it is not pathognomonic as may be found in other hypervascular lesions and in CSCS 11 21 22. In CBT, CT and MRI display a homogeneous and intense pattern of enhancement following intravenous contrast, while enhancement in schwannoma is less intense and dishomogeneous. Splaying of the carotid bifurcation, typical of CBT, can also be found in schwannoma arising from the lower four cranial nerves or the sympathetic chain 19; the main imaging criterion to differentiate CBT and a nerve sheath tumour is hypervascularity. This can be demonstrated by US, contrast CT, MRA and conventional angiography. In DSA sequences with contrast agent accumulation, the absence of arteriovenous shunts and a low-degree vascularity should suggest a schwannoma 20.

Paraganglioma can be differentiated from schwannoma on a radiologic basis as the former is isodense compared with muscle on pre-contrast CT scan, while in the post-contrast phase a more reliable homogeneous enhancement is appreciable. In post-gadolinium MRI sequences, paraganglioma shows extremely bright contrast enhancement in a characteristic "salt and pepper" pattern that is not pathognomonic, as may be found in other hypervascular lesions. However, paraganglioma is more cranial in the superior-medium latero- cervical neck region compared to schwannoma.

Schwannomas of the vagus nerve and the sympathetic chain cannot be distinguished without radiologic signs of separation between the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein. A superficial course of the vagus nerve on the mass or vagal connection with the tumour can be important elements to detect, respectively, a sympathetic or vagal origin of the tumour, but they are difficult to find by preoperative radiology 6. In our case, vagal schwannoma was excluded as there were no radiologic signs of separation between the common carotid artery and the internal jugular vein and no clinical signs of vagal involvement were evident. A slight anterior displacement of the internal carotid artery, probably due to the small size of the tumour, was not considered to be significant.

During surgery, the appearance of the tumour can suggest the right diagnosis if the lesion presents as a fusiform mass, eccentrically to the nerve and surrounded by a capsule. Complete surgical removal of the mass, without sacrificing nerve fibre, is possible only when the capsule is easily separable from the underlying fibres. When dissection of the capsule from the nerve is not easy and there are no signs of malignancy, functional loss can be minimized by opening the capsule longitudinally and removing the tumour from inside 6 23. Nevertheless, a CSCS can be uncommonly removed without sacrifice of some nervous fibres or section of the sympathetic trunk 4 8. Moreover, since cervical sympathetic chain damage is well tolerated, restoration of the nerve has only been rarely performed, while in vagal schwannomas the practice of nerve reconstruction is recommended 6. Thus, the majority of patients who have undergone intervention are reported to manifest some degree of Horner's syndrome, which is the most frequent complication after CSCS removal 4 7 8 18. The actual percentage of this complication and its impact on quality of life are not well known, but its frequency is estimated to be quite high, also in its definitive form. In our patient, a partial, well tolerated Horner's syndrome occurred on the right side of the face and is still present at 7 months of follow-up; therefore, only sympathetic fibres branching to the internal carotid artery were injured during surgery 4 19.

Conclusions

CSCS do not present with specific symptoms or imaging signs. Imaging examinations cannot reveal the exact origin of the tumour. Radiological investigations can only narrow diagnosis to lesions arising in the retro-styloid compartment of the parapharyngeal space, thus excluding lymphadenopathies and salivary gland tumours that originate in the pre-styloid compartment. Incisional biopsy presents some risk, and FNAC provides minor diagnostic value in compact neural tumours. The majority of patients have undergone intervention without a preoperative diagnosis, but only with a provisional suspect based on the exclusion of other similar tumours.

Only surgical observation of the lesion and the nerve from where it originates, and histologic examination of the specimen, can lead to a correct diagnosis. Nevertheless, an accurate preoperative workup is useful for surgical planning and informing the patient about any possible complications. Total resection is the treatment of choice for these tumours, but can only rarely be performed without sectioning the sympathetic trunk or damage to any nervous fascicle. Intervention often leaves the patient with some degree of Horner's syndrome, which is relatively well tolerated and should be discussed with the patient during preoperative counselling.

References

- 1.Colreavy MP, Lacy PD, Hughes J, et al. Head and neck schwannomas: a 10 years review. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:119–124. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cashman E, Skinner LJ, Timon C. Thyroid swelling: an unusual presentation of a cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:201–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, et al. Soft tissue tumors. Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 362–415. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aydin S, Sanli A, Tasdemir O, et al. Horner's syndrome postexcision of a huge cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Turk J Med Sci. 2007;37:185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souza JW, Williams JT, Dalton ML, et al. Schwannoma of the cervical chain: it's not a carotid body tumor. Am Surg. 2000;66:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozlugedik S, Ozcan M, Unal T, et al. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma: two different clinical presentations. Tumori. 2007;93:305–307. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toshiki Tomita. Diagnosis and treatment of CSCS: a review of 9 cases. Acta Otolaryngologica. 2009;129:324–339. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panneton JM, Rusnak BW. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannomas masquerading as carotid body tumors. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:519–524. doi: 10.1007/s100169910097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa M, Furukawa MK, Katoh K, et al. Differentiation between schwannoma of the vagus nerve and schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain by imaging diagnosis. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1548–1552. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199612000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Som PM, Sacher M, Stollman AL, et al. Common tumors of the parapharyngeal space: refined imaging diagnosis. Radiology. 1988;169:81–85. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.2843942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bocciolini C, Dall'olio D, Cavazza S, et al. Schwannoma of cervical sympathetic chain: assessment and management. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2005;25:191–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araujo CE, Ramos DM, Moyses RA, et al. Neck nerve trunks shwannomas: clinical features and postoperative neurologic outcome. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1579–1582. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817b0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber AL, Montandon C, Robson CD. Neurogenic tumors of the neck. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:1077–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CC, Wang CC, Liu SA, et al. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:956–960. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogose A, Hotta T, Morita T, et al. Tumors of peripheral nerves: correlation of symptoms, clinical signs, imaging features and histologic dignosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s002560050498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girolami U, Anthony DC, Frosch MP. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins pathologic basis of disease. Piladelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999. The central nerveous system; pp. 1293–1358. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikami Y, Hidaka T, Akisada T, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising in benign ancient schwannoma: A case report with an immunohistochemical study. Pathol Int. 2001;50:156–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh JS, Abenoza P, Galloway HR, et al. Peripheral (extracranial) nerve tumors: correlations of MR imaging and histologic findings. Radiology. 1992;183:341–346. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.2.1561333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzun L, Ugur MB, Ozdemir H. Cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma mimicking a carotid body tumor: a case report. Tumori. 2005;91:84–86. doi: 10.1177/030089160509100117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abramowitz J, Dion JE, Jensen ME, et al. Angiographic diagnosis and management of head and neck schwannomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:977–984. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hood RJ, Reibel JF, Jensen ME, et al. Schwannoma of the cervical sympathetic chain. The Virginia experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:48–51. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang CP, Hsiao JK, Ko JY. Splaying of the carotid bifurcation caused by a cervical sympathetic chain schwannoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:696–699. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheridan MF, Yim DWS. Cervical sympathetic schwannoma: a case report and review of the English literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:206–210. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]