Abstract

This study further evaluates the efficacy of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP). A diagnostically heterogeneous clinical sample of 37 patients with a principal anxiety disorder diagnosis was enrolled in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving up to 18 sessions of treatment and a 6-month follow-up period. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either immediate treatment with the UP (n=26) or delayed treatment, following a 16-week wait-list control period (WLC; n= 11). The UP resulted in significant improvement on measures of clinical severity, general symptoms of depression and anxiety, levels of negative and positive affect, and a measure of symptom interference in daily functioning across diagnoses. In comparison, participants in the WLC condition exhibited little to no change following the 16-week wait-list period. The effects of UP treatment were maintained over the 6-month follow-up period. Results from this RCT provide additional evidence for the efficacy of the UP in the treatment of anxiety and comorbid depressive disorders, and provide additional support for a transdiagnostic approach to the treatment of emotional disorders.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, cognitive-behavioral treatment, transdiagnostic, unified protocol

A number of treatment protocols utilizing cognitive-behavioral principles have been developed and refined over the past 30 years to address the significant public health issue posed by the emotional disorders (e.g., see Antony & Stein, 2009; Barlow, 2002, 2008; Hofmann & Smits, 2008; Norton & Price, 2007). Many of these treatments have undergone rigorous empirical testing, and clinicians now have a variety of evidence-based cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) protocols available to treat the full range of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) anxiety and mood disorder categories. CBT development has proceeded in line with a body of research characterizing and specifying the specific symptom-based syndromes that make up the current DSM-IV diagnostic classification system, and these research efforts have been invaluable to furthering our understanding of the psychopathology represented by these specific diagnoses and the development of psychosocial treatments to address them. However, these efforts have also resulted in a proliferation of diagnosis-specific treatment manuals, many of which have only minor and somewhat trivial variations in treatment procedures, with limited empirical support for these alterations. Whereas the development of these protocols was expected to facilitate training in empirically supported protocols, published manuals targeting single disorders have grown so numerous that there is little chance of becoming even familiar with most of them, let alone trained to competence, and no good way to choose among them. This is particularly problematic when faced with the clinical reality of high rates of comorbidity in patients, leaving clinicians in a position to choose among single-disorder protocols to tackle one presenting disorder at a time. This state of affairs has substantially diminished the public health significance of the availability of evidence-based psychological treatments and hindered their widespread dissemination (McHugh & Barlow, 2010).

Current evidence strongly argues for a more parsimonious approach to treating the emotional disorders. Research over the last few decades suggests considerable overlap among the various anxiety and mood disorders (see Barlow, 2004, for a review; Moses & Barlow, 2006), and this overlap is seen most clearly diagnostically, as evidenced by high rates of current and lifetime comorbidity (Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; Kessler, Berglund, & Demler, 2003; Kessler et al., 1996, 1998, 2005). One intriguing explanation for these high rates of comorbidity is that this pattern may be the result of what has been previously called a “general neurotic syndrome” (Andrews, 1990, 1996; Brown & Barlow, 2009; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow 1998; Tyrer, 1989). Under this conceptualization, heterogeneity in the expression of emotional disorder symptoms (e.g., individual differences in the prominence of social anxiety, panic attacks, anhedonia) is regarded as a trivial variation in the manifestation of a broader syndrome. If this is indeed the case, developing treatments that directly target this underlying syndrome, rather than symptom-specific variations of this syndrome, allows for the possibility of a much more parsimonious approach to treatment, and the potential to improve both dissemination and training efforts.

Research describing the origins and nature of this syndrome, best represented, perhaps as a set of interacting temperaments, has been reviewed in depth elsewhere (Allen, McHugh, & Barlow, 2008; Barlow, 2002; Brown, 2007; Suárez, Bennett, Goldstein, & Barlow, 2009). Taken together, evidence from these sources suggests that a common, underlying factor across disorders is the propensity toward increased emotional reactivity, coupled with a heightened tendency to view these experiences as aversive and attempts to alter, avoid, or control emotional responding. These common processes, emerging out of shared etiological factors, may be amenable to, and better addressed by, a single set of therapeutic principles (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004). Based on these advances, we developed the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP; Barlow, Ellard, et al., 2011; Barlow, Farchione, et al., 2011). The UP is a transdiagnostic, emotion-focused CBT designed to be applicable to all anxiety and unipolar mood disorders, and possibly other disorders with strong emotional components such as many somatoform and dissociative disorders. The UP capitalizes on the contributions made by cognitive-behavioral theorists by distilling and incorporating the common principles among existing empirically supported psychological treatments—namely, restructuring maladaptive cognitive appraisals, changing maladaptive action tendencies associated with emotions, preventing emotion avoidance, and utilizing emotion exposure procedures (e.g., Barlow, 1985; Barlow & Craske, 1989; Beck, 1972; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1987; Clark & Wells, 1995; Craske, Barlow, & O’Leary, 1992; Linehan, 1993). In addition, the UP places explicit emphasis on the adaptive, functional nature of emotions, building the patient’s awareness of the contribution of cognitions, physical sensations, and behaviors to unfolding emotional experiences, and identifying and altering maladaptive reactions to these experiences.

Early versions of the UP were pilot tested in two open trials of patients with diagnostically heterogeneous anxiety disorders seeking treatment at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders (CARD) at Boston University (Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione, & Barlow, 2010). Full descriptions of these initial pilot trials can be found in Ellard et al. In the first trial, which included a sample of 18 participants, significant pre- to posttreatment effects were found across disorders on a variety of outcome measures, but it became apparent that further modifications to the protocol were needed. Subsequently, in a second open trial of 15 patients, treatment with the UP resulted in more robust pre- to posttreatment effects. In order to determine the clinical significance of outcomes in this trial, we examined the proportion of individuals meeting criteria for treatment responder status and high-end-state functioning (HESF), using a conservative adaptation of algorithms reported in other similar trials of CBT for anxiety (e.g., Borkovec, Newman, Pincus, & Lytle, 2002; Ladouceur et al., 2000; Roemer & Orsillo, 2007; Tolin, Maltby, Diefenbach, Hannan, & Worhunsky, 2004). Using this algorithm, 73% of patients achieved responder status, and 60% reached HESF. The response for comorbid disorders was also promising, with 64% of patients attaining both responder status and HESF. These results were sustained at 6-month follow-up, with 85% of those followed (N=13) achieving responder status and 69% achieving HESF on principal (most interfering) diagnoses, and 80% achieving responder status and greater than half achieving HESF on comorbid disorders. In keeping with the UP’s focus on the transdiagnostic processing of emotional experiences, analyses of the effect of treatment on negative affectivity, as assessed by the negative affect subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) revealed that by posttreatment, 67% of patients had achieved scores within a normal range, as compared to only 27% at pretreatment. By 6-month follow-up, 82% of patients achieved scores within a normal range.

In the current study, we present data from an initial randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the efficacy of the current, published version of the UP (Barlow, Ellard, et al., 2011; Barlow, Farchione, et al., 2011) in 37 outpatients who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder, relative to a wait-list control (WLC) condition. Treatment with the UP followed the same protocol first described in Ellard et al. (2010), with the additional inclusion of techniques for enhancing motivation to engage in treatment (Miller & Rollnick, 1991, 2002; Westra, Arkowitz, & Dozois, 2009; Westra & Dozois, 2006). This addition was in response to the results of research by Westra and Dozois (2006) and Westra et al. (2009) indicating that motivational interviewing (MI) may enhance the efficacy of CBT for anxiety disorders. The current version also has a greater emphasis on positive emotion, both as a trigger for maladaptive emotion avoidance and as a target for emotion exposures. We expected that the UP would be superior to the WLC on principal outcome measures, and that treatment gains would be maintained over a 6-month follow-up period. Consistent with the transdiagnostic rationale outlined above, we hypothesized that the UP would be efficacious across each of the following principal specific anxiety disorder categories represented by the sample: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SOC), panic disorder with agoraphobia (PDA), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). We also expected that the UP would result in reductions in comorbid disorder severity at both acute and follow-up assessments.

Method

STUDY DESIGN

A randomized trial comparing the UP to a WLC/delayed-treatment condition was conducted. Patients were randomized to condition based on a 2:1 allocation ratio (Woods et al., 1998). Participants assigned to immediate treatment with the UP (n=26) were assessed before treatment, at the end of treatment, and after a 6-month follow-up period. Wait-list participants (n=11) were assessed at the beginning and end of a 16-week wait-list period. Following the post-wait-list assessment, these patients were immediately assigned to the treatment protocol. Additional assessments were then conducted at the end of treatment and following a 6-month follow-up.

PARTICIPANTS

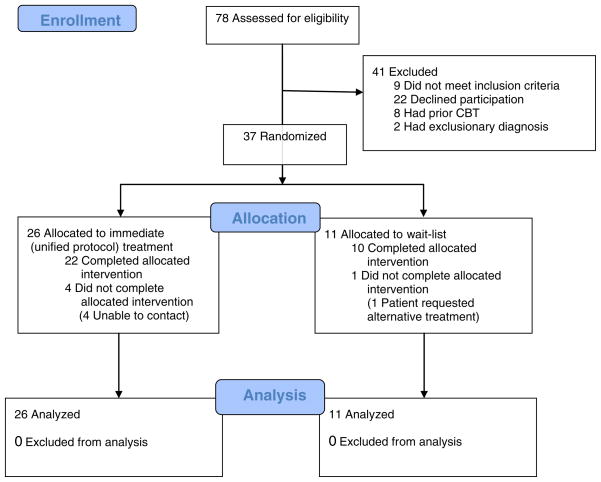

Participants were recruited from a pool of individuals seeking treatment at the CARD. Figure 1 summarizes participant enrollment and flow through Phase 3 of the study. Recruitment was designed to be broadly inclusive, with few exclusion criteria. To be eligible for participation, patients had to receive a principal (most interfering and severe) diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, as assessed using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV–Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L; Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994; see description below); be 18 years or older; be fluent in English; be able to attend all treatment sessions and assessments; and provide informed consent.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram illustrating participant flow during Phase 3 of the study. Participants were tracked during enrollment, allocation, and analysis.

Exclusion criteria consisted primarily of those existing conditions that in a clinical context would have required prioritization for immediate treatment or simultaneous treatment that could interact with the study treatment in unknown ways; for instance, current DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or organic mental disorder, clear and current suicidal risk, or current or recent (within 3 months) history of substance abuse or drug dependence, with the exception of nicotine, marijuana, and caffeine. Individuals were also excluded if they previously received at least eight sessions of psychological treatment consisting of clear and identifiable cognitive-behavioral principles, such as cognitive restructuring and exposure, within the past 5 years.

Forty-one of 78 patients assessed for eligibility were excluded from the trial. Of these, nine patients failed to meet inclusion criteria and two patients had an exclusionary diagnosis. In addition, eight patients were deemed ineligible because they had previously received an adequate trial of CBT. Finally, 22 patients declined to participate, with 15 individuals being unwilling to risk possible randomization to the WLC. The frequency of patients who declined participation in this trial is consistent with other disorder specific trials conducted at the CARD (e.g., Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, 2000). Individuals who were excluded from the study did not appear to present with more severe psychopathology relative to patients who were enrolled and randomized, based on information taken from the initial diagnostic evaluation.

A total of 37 patients consented to treatment and were randomized to either the immediate- or delayed-treatment conditions. The UP group consisted of 10 males and 16 females (mean age= 29.38, SD=9.86, range=19 to 52 years) and the WLC group included 5 males and 6 females (mean age=30.64, SD=9.15, range=19 to 43 years). The study sample was primarily Caucasian 94.6% (n=35). The two groups did not differ in mean age (t=0.36, p>0.05) or gender ratio (Fisher’s exact test, p>0.05, two-sided). Sixteen individuals were taking psychotropic medications at the time of enrollment and randomization. All individuals were stable on the same dose for at least 3 months prior to enrolling in the study as a condition for participation in the study, and all agreed to maintain these dosages and medications for the duration of the study. Information on medication stability during the trial was available for 21 patients, including 11 of the 16 patients who were taking psychotropic medications at the time of enrollment. For all patients where these data were available, no medication changes were reported during the trial. Twenty-nine individuals had received prior psychological treatment for anxiety or mood disorders. Principal diagnoses represented included GAD (n=7), SOC (n=8), OCD (n=8), PDA (n=8), anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (Anx NOS; n=2), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; n=1). Three participants had co-principal diagnoses (two diagnoses of equal severity). For these individuals the co-principal diagnoses were SOC and Anx NOS, GAD and SOC, and OCD and PDA. Participants had an average number of 2.16 diagnoses at the initial assessment (SD=1.19; range=1 to 5 diagnoses). Twelve patients met criteria for a co-occurring depressive disorder at intake, including major depressive disorder (MDD; n=8), dysthymia (DYS; n=2), and depressive disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS; n=2). Seven of these individuals were in the UP condition, while five were assigned to WLC.

Four of the 26 patients assigned to immediate treatment with the UP failed to complete it. Unfortunately, these patients were unable to be contacted after discontinuing treatment, so reasons for discontinuation are unknown. One patient randomized to the WLC failed to complete the 16-week wait-list period and instead chose to seek alternative treatment.

TREATMENT

Treatment consisted of a maximum of 18, 60-minute individual treatment sessions. The UP consists of five core treatment modules that were designed to target key aspects of emotional processing and regulation of emotional experiences: (a) increasing present-focused emotion awareness, (b) increasing cognitive flexibility, (c) identifying and preventing patterns of emotion avoidance and maladaptive emotion-driven behaviors (EDBs), (d) increasing awareness and tolerance of emotion-related physical sensations, and (e) interoceptive and situation-based emotion-focused exposure. The five core modules are preceded by a module focused on enhancing motivation and readiness for change and treatment engagement, as well as an introductory module educating patients on the nature of emotions and providing a framework for understanding their emotional experiences. A final module consists of reviewing progress over treatment and developing relapse prevention strategies. For full details on manual development and specific modifications from earlier versions, see Ellard et al. (2010).

THERAPISTS AND TREATMENT INTEGRITY

Therapists for the study were three doctoral students with 2 to 4 years of experience and one licensed doctoral-level psychologist with 7 years of experience. All therapists were directly involved in the initial development of the treatment protocol. Treatment was provided under the close supervision of a licensed senior team member who was also part of the development team. Treatment adherence was closely monitored during weekly supervision and manual development meetings, though it was not systematically assessed.

ASSESSMENT

Intake diagnoses were established using the ADIS-IV-L (Di Nardo et al., 1994). This semistructured, diagnostic clinical interview focuses on DSM-IV diagnoses of anxiety disorders and their accompanying mood states, somatoform disorders, and substance and alcohol use. Principal and additional diagnoses are assigned a clinical severity rating (CSR) on a scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 8 (extremely severe symptoms), with a rating of 4 or above (definitely disturbing/disabling) passing the clinical threshold for DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. This measure has demonstrated excellent to acceptable interrater reliability for the anxiety and mood disorders (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). The full ADIS-IV-L (focusing on current and lifetime diagnoses) was administered only at the original intake. An abbreviated version of the ADIS, focusing only on current symptomatology (Mini-ADIS-IV; Brown, Di Nardo, & Barlow, 1994) was administered at posttreatment and follow-up. These study assessments were conducted by independent evaluators (IEs) who were blind to treatment condition allocation. All ADIS interviewers were trained to a very high level of reliability and underwent a rigorous certification process (see Brown, Di Nardo, et al., 2001). In addition, study staff held weekly meetings during which all initial diagnostic interviews conducted that week were discussed in the presence of senior clinicians, and in the instance of diagnostic disagreement the sources of these differences were reviewed and a consensus diagnosis was reached.

General symptoms of anxiety and depression were evaluated by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS; Hamilton, 1959) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960), administered by IEs in accordance with the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale (SIGH-A and SIGH-D, respectively; Shear, Vander Bilt, & Rucci, 2001; Williams, 1988), and the self-report Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988; Beck & Steer, 1990; Steer, Ranieri, Beck, & Clark, 1993). In addition, to assess positive and negative affect, the PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) was included.

Several additional measures were used to assess diagnosis-specific symptoms. Current GAD symptom severity was assessed using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990). Current SOC symptoms were assessed using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998). Current symptoms related to panic were assessed using the Panic Disorder Severity Scale–Self-Report Version (PDSS-SR; Houck, Spiegel, Shear, & Rucci, 2002). Finally, current OCD symptom severity was assessed using the self-report version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989) developed by Baer (1991).

Finally, the five-item Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Marks, Connolly, & Hallam, 1973; Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002) was used to assess the degree of interference caused by the patient’s symptoms in the areas of work, home management, private leisure, social leisure, and family relationships. For the purposes of this study, clinician ratings of interference are reported.

DATA ANALYSIS

The raw data were analyzed using a latent variable software program (Mplus 5.2; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009). All primary study analyses were conducted as intent-to-treat analyses, utilizing all available data. Missing data were accommodated in all models by using direct maximum likelihood estimation. Additional analyses examining categorical or dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0, which did not allow for accommodation of missing data using direct maximum likelihood estimation. Thus analyses evaluating categorical outcomes (e.g., treatment responder status) were conducted using listwise deletion.

Results

EFFICACY AT POSTTREATMENT

In order to assess the effect of treatment on outcome, a series of regression models were estimated using direct maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus. For each study outcome, posttreatment scores were regressed onto a dummy code variable representing treatment condition (WLC=0, UP=1) as well as the corresponding pretreatment score. Results from these analyses are presented in Table 1. Standardized regression coefficients representing the direct effect of the treatment condition variable and their corresponding significance tests are presented, along with effect size estimates (Hedges g) that include a correction for small sample sizes. Regarding diagnostic severity, UP produced strong reductions on ADIS-IV CSRs for principal diagnoses compared to WLC (β=−.58, p<.001, Hedges g=1.39). Strong effects were also demonstrated on general symptom measures, including self-reported depression (BDI-II; β=−.46, p<.001, Hedges g=1.11) and anxiety (BAI; β=−.32, p=.034, Hedges g=.56), as well as clinician-rated depression (SIGH-D; β=−.26, p=.089, Hedges g=.52) and anxiety (SIGH-A; β=−.50, p<.001, Hedges g=1.10) measures. The UP also demonstrated significant reductions on a clinician-rated measure of functional impairment (WSAS; β=−.44, p<.001, Hedges g=1.09), as well as moderate effects on self-report measures of temperament compared to WLC. Of note, the effects on increases in positive affectivity (PANAS-PA; β=.28, p=.001, Hedges g=−.77) were somewhat larger in magnitude than those for decreases in negative affectivity (PANAS-NA; β=−.31, p=.001, Hedges g=.40).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Between-Treatment Effect Sizes for Primary Outcome Variables (N=37)

| Measure | UP (n=26)

|

WLC (n=11)

|

B | Z Test | Hedges’s g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre Mean (SD) |

Post Mean (SD) |

Pre Mean (SD) |

Post Mean (SD) |

||||

| ADIS (Co-)Principal Dx CSR | 5.23 (0.89) | 3.18 (1.55) | 5.09 (0.79) | 5.14 (0.80) | −.58 | −5.44*** | 1.39 |

| SIGH-D | 10.35 (5.77) | 5.49 (4.63) | 10.09 (3.87) | 7.85 (4.01) | −.26 | −1.70 | 0.52 |

| SIGH-A | 16.15 (7.91) | 7.39 (5.37) | 14.36 (5.19) | 13.08 (4.22) | −.50 | −3.88*** | 1.10 |

| BDI-II | 11.96 (7.53) | 4.21 (4.43) | 11.73 (9.92) | 11.45 (9.64) | −.46 | −4.00*** | 1.11 |

| BAI | 19.08 (9.93) | 8.27 (6.51) | 16.91 (6.97) | 12.22 (7.93) | −.32 | −2.12* | 0.56 |

| WSAS | 16.04 (6.53) | 7.62 (5.40) | 16.46 (2.39) | 13.14 (3.66) | −.44 | −3.32*** | 1.09 |

| PANAS-NA | 26.62 (5.48) | 20.57 (4.95) | 24.36 (5.21) | 22.86 (7.03) | −.31 | −2.23* | 0.40 |

| PANAS-PA | 28.81 (6.27) | 32.84 (6.50) | 28.00 (7.19) | 27.17 (8.61) | .28 | 2.32* | −0.77 |

Note: UP = unified protocol; WLC = wait-list control; ADIS = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; CSR = clinical severity rating; SIGH-D and SIGH-A = Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scale, respectively; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Negative Affectivity; PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Positive Affectivity. Means and standard deviations at posttreatment estimated in Mplus using direct maximum likelihood estimation techniques. Positive effect sizes denote a decrease in scores, negative effect sizes denote an increase. Hedges’s g effect sizes presented contrast the post scores for the UP and WLC conditions.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE AT POSTTREATMENT

In order to evaluate the clinical significance of the observed effects at posttreatment, the effect of treatment on diagnostic status was evaluated and compared using Fisher’s exact test to compare differential rates of subclinical diagnoses across the treatment conditions. The UP had significantly (p=.006) more patients (50%) achieve subclinical status on their principal diagnosis than WLC (0%) and significantly (p=.013) more patients (45%) who no longer met criteria for any clinical diagnoses than WLC (0%). Although not statistically significant (p=.33), the UP also had more participants who no longer met criteria for any of their comorbid diagnoses at posttreatment (50%) than WLC (17%). Also, of the patients who were diagnosed with a comorbid depressive disorder at intake, a greater proportion of individuals receiving the UP (86%) achieved subclinical status for their depressive disorder at posttreatment relative to WLC (40%). However, the difference between these response rates across conditions was not statistically significant (p=.22). To further evaluate the clinical significance of the observed effects of UP at posttreatment, rates of treatment responder status and HESF were calculated within each condition and compared using Fisher’s exact test. Treatment responder status and HESF was defined in accordance with criteria used in a previous evaluation of the UP (Ellard et al., 2010), as described above, with one minor variation. Patients were defined as meeting responder status if they (a) achieved a 30% or greater improvement on the ADIS-IV CSR for their principal diagnosis or no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal diagnosis, based on a posttreatment ADIS CSR of 3 or lower; and (b) achieved a 30% or greater improvement on either the WSAS, or the corresponding diagnosis-specific self-report measure for their principal diagnosis, or both. For example, responder status for a patient with a principal diagnosis of OCD would be determined by examining the amount of improvement on the OCD CSR, WSAS, and Y-BOCS. Based on these criteria, 59% of the UP group was classified as responders at posttreatment, compared to 0% of WLC (p=.002). Patients were classified as meeting criteria for HESF if they (a) no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal diagnosis, based on a posttreatment ADIS CSR of 3 or lower; and (b) fell within the normal range on either the WSAS or their diagnosis-specific measure. Using this definition, 50% of the UP group achieved HESF, compared to 0% of WLC (p=.006).

MAINTENANCE OF TREATMENT GAINS

Hypotheses regarding the maintenance of treatment gains were evaluated using the larger sample of treatment initiators (e.g., all patients who started treatment following completion of the wait-list, in addition to those randomized to UP). Two of the 11 patients randomized to WLC failed to initiate treatment with the UP. One patient withdrew from the wait-list in order to begin immediate treatment elsewhere, as previously noted, and another patient moved out of state immediately following the post-wait-list assessment and so was unable to begin treatment. Thus, the treatment initiator sample is comprised of 35 patients. Of the nine wait-list participants who initiated treatment, two failed to complete it. Patients in the treatment initiator sample completed an average of 15.26 sessions of treatment (SD=4.60, range=2 to 18 sessions). Descriptive statistics and within-treatment effect size estimates (standardized gain, ESsg) for posttreatment and follow-up are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Within-Treatment Effect Sizes for Primary Outcome Variables for Treatment Initiators (N=35)

| Measure | Pre

|

Post

|

FU

|

Pre–Post

|

Pre-FU

|

Post-FU

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ESsg | ESsg | ESsg | |

| ADIS (Co-)Principal Dx CSR | 5.19 (0.88) | 3.26 (1.61) | 2.46 (1.69) | 1.43 | 1.93 | .48 |

| SIGH-D | 9.74 (5.53) | 5.76 (5.60) | 5.24 (5.40) | .72 | .83 | .09 |

| SIGH-A | 15.34 (7.33) | 7.93 (6.04) | 7.33 (5.78) | 1.10 | 1.21 | .10 |

| BDI-II | 11.76 (8.41) | 4.36 (5.63) | 4.47 (7.06) | 1.00 | .94 | −.02 |

| BAI | 17.46 (9.90) | 8.01 (6.17) | 8.65 (7.05) | 1.13 | 1.02 | −.10 |

| WSAS | 15.26 (6.11) | 8.07 (6.32) | 5.45 (4.86) | 1.16 | 1.76 | .44 |

| PANAS-NA | 25.54 (6.11) | 20.64 (5.41) | 20.03 (6.94) | .85 | .84 | .09 |

| PANAS-PA | 28.71 (7.01) | 32.34 (6.57) | 32.20 (5.20) | −.53 | −.56 | .02 |

Note. FU = follow-up; ADIS = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; CSR = clinical severity rating; SIGH-D and SIGH-A = Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scale, respectively; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Negative Affectivity; PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Positive Affectivity. Positive effect sizes denote a decrease in scores, negative effect sizes denote an increase. Means and standard deviations estimated in Mplus using direct maximum likelihood estimation techniques.

SPECIFICITY OF TREATMENT GAINS

In order to examine the hypothesis that treatment gains with the UP would occur across diagnostic categories, within-treatment effect size estimates (ESsg) for primary diagnosis-specific outcomes were calculated separately among patients with a principal diagnosis of GAD (n=7), SOC (n=8), PDA (n=7), and OCD (n=8) at pretreatment. Given the small number of patients who received a principal diagnosis of PTSD (n=1) and Anx NOS (n=2), effect size estimates were not calculated for these diagnoses. As shown in Table 3, the effect size estimates for the ADIS CSR ranged from 1.43 to 1.60 at posttreatment, and increased from 1.39 to 2.67 at follow-up. Effect size estimates for diagnosis-specific self-report measures were largely consistent with the ADIS CSR. All effect size estimates for ADIS CSRs and diagnosis-specific self-report measures were in the very large range, with the exception of the SIAS (the diagnosis-specific self-report measure for SOC), which was in the moderate range, at both posttreatment and follow-up. In addition, the majority of effect size estimates increased from posttreatment to follow-up. The SIAS and PSWQ (diagnosis-specific self-report measure for SOC and GAD, respectively) were the only two measures that did not follow this pattern.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Within-Treatment Effect Sizes for Diagnosis-Specific Outcome Variables for Treatment Initiators by Principal Diagnosis for Four Primary Disorders

| Measure | Pre

|

Post

|

FU

|

Pre–Post

|

Pre-FU

|

Post-FU

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ESsg | ESsg | ESsg | |

| GAD (N=7) | ||||||

| ADIS Principal Dx CSR | 5.50 (0.46) | 3.33 (1.97) | 2.67 (2.07) | 1.44 | 1.39 | .33 |

| PSWQ | 70.86 (4.76) | 50.43 (15.38) | 57.31 (14.70) | 1.42 | 1.01 | −.46 |

| SOC (N=8) | ||||||

| ADIS Principal Dx CSR | 5.00 (0.00)a | 3.80 (0.75) | 3.40 (0.80) | 1.60 | 2.00 | .48 |

| SIAS | 41.88 (14.52) | 33.78 (16.82) | 35.69 (9.62) | .49 | .46 | −.11 |

| PDA (N=7) | ||||||

| ADIS Principal Dx CSR | 5.14 (1.12) | 3.04 (1.74) | 2.14 (1.12) | 1.43 | 2.67 | .44 |

| PDSS | 12.86 (5.03) | 4.16 (4.07) | 2.14 (2.64) | 1.91 | 2.70 | .39 |

| OCD (N=8) | ||||||

| ADIS Principal Dx CSR | 5.38 (0.99) | 3.50 (1.41) | 2.17 (1.73) | 1.51 | 2.15 | .83 |

| Y-BOCS | 18.75 (5.97) | 13.25 (7.15) | 10.08 (6.15) | .83 | 1.43 | .44 |

All patients had the same CSR at pretreatment, so the posttreatment and follow-up SDs were used to calculate effect sizes, as opposed to the pooled SD.

Note: FU = follow-up; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; ADIS = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule; CSR = clinical severity rating; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; SOC = social anxiety disorder; SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; PDA = panic disorder with agoraphobia; PDSS = Panic Disorder Severity Scale; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Means and standard deviations at post estimated in Mplus using direct maximum likelihood estimation techniques. Positive effect sizes denote a decrease in scores, negative effect sizes denote an increase.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE AMONG TREATMENT INITIATORS

The same definitions of responder status and HESF were used to evaluate the clinical significance of treatment gains in the treatment initiator sample at posttreatment and follow-up for both principal and comorbid diagnoses (see Table 4). Overall, 52% of patients achieved subclinical status on their principal diagnosis at posttreatment and this number increased to 71% by the end of the follow-up period. When examining all diagnoses, 45% achieved subclinical status on all of their clinical diagnoses at posttreatment, while 64% achieved subclinical status on all of their clinical diagnoses by follow-up. At posttreatment, 59% of patients were classified as treatment responders on their principal diagnoses and this number increased to 71% at follow-up. Similarly, 52% of patients achieved HESF on their principal diagnoses at posttreatment, with 64% achieving HESF at follow-up.

Table 4.

Proportion of Treatment Initiators Who Achieved Subclinical, Responder, or High-End-State Functioning Status on Principal, Comorbid, or All Diagnoses at Posttreatment (n=29) and Follow-Up (n=28) Assessments

| Posttreatment

|

Follow-Up

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % Subclinical | % Responder | % HESF | n | % Subclinical | % Responder | % HESF | |

| Principal (or Co-Principal) Dx at Pretreatment Assessment | ||||||||

| All (Co-)Principal Diagnoses | 29 | 52% | 59% | 52% | 28 | 71% | 71% | 64% |

| PDA | 6 | 67% | 100% | 67% | 7 | 86% | 86% | 86% |

| GAD | 6 | 50% | 50% | 50% | 6 | 67% | 67% | 50% |

| SOC | 5 | 40% | 20% | 40% | 5 | 40% | 40% | 20% |

| OCD | 8 | 50% | 63% | 50% | 6 | 83% | 83% | 83% |

| Anx NOS | 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 2 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Co-principal diagnoses | 2 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2 | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| Individuals with no comorbid dx | 10 | 90% | 70% | 90% | 11 | 73% | 73% | 73% |

| Comorbid Diagnoses at Pretreatment Assessment | ||||||||

| All Comorbid Diagnosesa | 32 | 47% | 38% | 41% | 29 | 76% | 62% | 72% |

| PDA | 2 | 100% | 0% | 50% | 2 | 100% | 0% | 50% |

| GAD | 7 | 43% | 29% | 29% | 6 | 67% | 67% | 67% |

| SOC | 5 | 20% | 40% | 20% | 4 | 50% | 50% | 50% |

| OCD | 2 | 50% | 50% | 50% | 2 | 100% | 50% | 100% |

| MDD/DYS/DDNOS | 9 | 67% | 67% | 67% | 9 | 89% | 89% | 89% |

| PTSD | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Specific Phobia | 4 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3 | 33% | 33% | 33% |

| Tourette’s | 1 | 100% | 0% | 100% | 1 | 100% | 0% | 100% |

| Hypochondriasis | 1 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| All Principal and Comorbid Diagnoses | 29 | 45% | 48% | 45% | 28 | 64% | 61% | 61% |

Some individuals had multiple comorbid diagnoses; diagnosis-specific measures were not available for PTSD, specific phobia, Tourette’s, and hypochondriasis so status calculations for theses diagnoses were based solely on clinical severity ratings and Work and Social Adjustment Scale ratings. Note also that some cases reached high-end-state functioning (HESF) without meeting clinical responder status. In all instances, these individuals were hovering on the threshold between clinical and subclinical status but all became subclinical without necessarily moving sufficiently on other measures to meet “responder” criteria.

Note. PDA = panic disorder with agoraphobia; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SOC = social anxiety disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; Anx NOS = anxiety disorder not otherwise specified; MDD/DYS/DDNOS = major depressive disorder/dysthymia/-depressive disorder not otherwise specified; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE ACROSS PRINCIPAL AND COMORBID DIAGNOSES

In order to examine the applicability and clinical significance of treatment gains with the UP across diagnostic categories, the proportion of treatment initiators who achieved subclinical status, treatment responder status, and high-end-state functioning at posttreatment and follow-up across principal and comorbid diagnoses are also presented in Table 4. Chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate whether the response rates varied significantly across the four primary disorders included in this study (GAD, OCD, PDA, and SOC). The differences in the proportion of individuals achieving subclinical status at posttreatment between the principal diagnoses of GAD (50%), OCD (50%), PDA (67%), and SOC (40%) were not statistically significant, χ2(df=3)= .83, p=.84. There was more variability in the proportion of individuals achieving responder status at posttreatment between the principal diagnoses of GAD (50%), OCD (63%), PDA (100%), and SOC (20%), but these differences did not achieve statistical significance, χ2(df=3)=7.60, p=.06. The differences in the proportion of individuals achieving HESF status at posttreatment between the principal diagnoses of GAD (50%), OCD (50%), PDA (67%), and SOC (40%) were also not statistically significant, χ2(df=3)=.83, p=.84. Although these comparisons are limited by the small sample sizes of each diagnostic category, they provide preliminary evidence that the UP has equivalent effects in terms of clinical significance across the four primary anxiety disorders examined in this trial.

The UP also demonstrated robust effects on response rates for comorbid diagnoses at posttreatment and follow-up. Across diagnostic categories, 47% of comorbid diagnoses achieved subclinical status at posttreatment, whereas 76% of all comorbid diagnoses achieved subclinical status by follow-up. Thirty-eight percent of comorbid diagnoses achieved responder status at posttreatment, whereas 62% of all comorbid diagnoses achieved responder status by follow-up. Finally, 41% of comorbid diagnoses achieved HESF status at posttreatment, with 72% of all comorbid diagnoses achieving HESF status by follow-up. Of particular note are the response rates for the nine individuals with a mood disorder of some kind. The majority of individuals (67%) with a comorbid mood disorder achieved subclinical, responder, and HESF status at posttreatment, with the proportion achieving subclinical, responder, and HESF status at follow-up increasing to 89% for mood disorders. These results indicate that the UP had robust effects across both principal and comorbid conditions and that the UP may also be effective at treating depression.

Discussion

The results of the present study provide additional support for the UP as a transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety disorders. Treatment with the UP resulted in significant reductions in diagnosis-specific symptom severity across both principal and comorbid disorders, as well as significant decreases in functional impairment. As predicted, patients receiving the UP demonstrated significant improvement relative to WLC, and controlled effect sizes (relative to WLC) on all measures were large. In addition, patients receiving the UP evidenced greater clinically meaningful change, relative to patients in the WLC, with 59% classified as responders at posttreatment, and 50% achieving HESF, as compared to 0% of patients in the WLC. Patients receiving the UP also demonstrated significant, moderate effects on measures of temperament, compared to WLC. Patients continued to show improvements 6 months following termination from acute treatment, lending preliminary support to the durability of the treatment effects over time.

Importantly, the UP was effective in the treatment of a range of anxiety disorders, including GAD, SOC, PDA, and OCD, yielding effect sizes comparable to treatments targeting disorder-specific symptoms (Hofmann & Smits, 2008). More than half of the patients receiving the UP no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal diagnosis. More significantly, almost half (45%) of these patients no longer met criteria for any clinical diagnosis at posttreatment, and more than half (64%) of these patients no longer met criteria for any clinical diagnosis at follow-up. Analyzing specific anxiety disorder categories included in this study (GAD, SOC, PDA, and OCD) revealed some differences in treatment response, depending on the principal diagnosis; however, these differences should be interpreted with caution, as the sample sizes for individual diagnoses are small, with an average sample size of seven.

Interestingly, the UP evidenced moderate to large treatment effects on measures of temperamental affectivity, with effects on positive affectivity being somewhat larger than those for negative affectivity when contrasting the UP with the WLC condition. These results make sense in the context of the overarching rationale of the UP, wherein affective processing is directly targeted. Negative emotional experiences are viewed not as something aversive and in need of reduction, but as adaptive and functional, and an emphasis instead is placed on reducing the affective reactions toward negative emotions, not negative emotions themselves. In addition, the revised version of the UP places specific emphasis on reducing avoidance of positive emotions, and thereby encouraging greater approach to positive emotional experiences. Future, controlled mediational analyses will allow a more concise understanding of the relationship between treatment with the UP and changes in temperamental measures of negative and positive affectivity.

Transdiagnostic treatments targeting core “higher-order” factors offer a more parsimonious approach to treatment planning that eliminates the need for multiple diagnosis-specific manuals (Mansell, Harvey, Watkins, & Shafran, 2009). In addition, other researchers have begun to consider how existing evidence-based therapeutic principles could be effectively applied transdiagnostically on a more empirical basis using evidence-based modules of behavior change procedures (e.g., Erickson, Janeck, & Tallman, 2007; Harvey et al., 2004; Mansell et al., 2009; McEvoy & Nathan, 2007; McEvoy, Nathan, & Norton, 2009; Norton, 2008; Norton & Hope, 2005; Norton & Philipp, 2008). Some of these efforts focus on identifying and correcting deficits in functioning rather than focusing on cross-cutting dimensions of psychopathology.

In what is perhaps the most advanced effort along these lines, Fairburn and colleagues (Fairburn, 2008; Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Fairburn et al., 2009 ) have developed a transdiagnostic approach to eating disorders based on shared psychological dimensions of these disorders, an approach similar to but predating ours (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004). Whatever the strategy, these transdiagnostic approaches may not only prove to be more effective, but also have significant implications for broader dissemination efforts. More specifically, transdiagnostic treatments have the potential to reduce the amount of time and effort that is required for adequate training, a factor that has hindered dissemination efforts in the past (Addis, Wade, & Hatgis, 1999; Barlow, Levitt, & Bufka, 1999; McHugh & Barlow, 2010). Also, if found to be effective, these treatments may prove to have considerable clinical utility. Clinicians are often faced with the difficult task of treating individuals with complex clinical presentations that require them to use multiple protocols or to tackle several problems at once, with little empirical data to guide them. Transdiagnostic treatments may help eliminate the need for multiple diagnosis-specific treatment manuals and simplify treatment planning, overall.

There were several limitations of the present study. First, the small sample size may have limited our ability to detect significant differences in some of our analyses. Although we provide effect size estimates to address this issue, it points to the importance of replication with a larger sample. Second, diagnostic severity ratings by the IE subsequent to the initial diagnostic intake were not systematically checked for reliability, nor was treatment fidelity evaluated in this trial, although all therapists were closely supervised weekly. Finally, the present study did not include an active treatment comparison. As a result, no firm conclusions can be drawn about therapy processes, nor can we account for the potential effects of common therapeutic factors, such as therapist attention.

Given these limitations, a larger-scale efficacy trial of the UP is needed to replicate and extend on the preliminary findings from the present study. We are currently in the process of the next phase of testing for the UP, conducting a large noninferiority clinical trial directly comparing the UP to single-diagnosis protocols (SDPs). The results of this trial should help to establish whether the UP can be considered at least equally efficacious to established SDPs in the treatment of a range of anxiety disorders. If this is the case, the UP may represent a more efficient and possibly more effective strategy for the treatment of anxiety and related disorders and comorbid conditions than the current reliance upon SDPs, and ultimately may facilitate improvement in both training and dissemination efforts. If this can be accomplished, it represents an important step toward tackling the significant and costly public health issue posed by these disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a NIMH grant awarded to Dr. David H. Barlow (R34-MH070693) and a NIAAA grant awarded to Dr. Domenic Ciraulo (R01-AA013727). The authors would like to thank Benjamin Emmert-Aronson, Alex De Nadai, and Zofia A. Wilamowska for their invaluable assistance in this project.

Contributor Information

Todd J. Farchione, Boston University

Christopher P. Fairholme, Boston University

Kristen K. Ellard, Boston University

Christina L. Boisseau, Butler Hospital, Brown University

Johanna Thompson-Hollands, Boston University.

Jenna R. Carl, Boston University

Matthew W. Gallagher, Boston University

David H. Barlow, Boston University

References

- Addis ME, Wade WA, Hatgis C. Barriers to dissemination of evidence-based practices: Addressing practitioners’ concerns about manual-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;4:430–441. [Google Scholar]

- Allen LB, McHugh RK, Barlow DH. Emotional disorders: A unified protocol. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A stepy-tep treatment manual. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 216–249. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. Classification of neurotic disorders. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1990;83:606–607. doi: 10.1177/014107689008301003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. Comorbidity in neurotic disorders: The similarities are more important than the differences. In: Rapee RM, editor. Current controversies in the anxiety disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM, Stein MB, editors. Handbook of anxiety disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baer L. Getting control: Overcoming your obsessions and compulsions. Boston: Little, Brown; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Psychological treatments. American Psychologist. 2004;59(9):869–878. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.9.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. 4. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behaviour Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Craske MG. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behaviour Therapy. 1989;20(2):261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Farchione TJ, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Client workbook. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:2529–2536. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Levitt JT, Bufka LF. The dissemination of empirically supported treatments: A view to the future. Research and Therapy. 1999;37(Suppl 1):S147–S162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck self-concept test. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2(2):191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Newman MG, Pincus AL, Lytle R. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the role of interpersonal problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):288–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:313–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21(3):256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Treatment follow-up version (Mini-ADIS-IV) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg R, Liebowitz M, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH, O’Leary T. Mastery of your anxiety and worry. Albany, NY: Graywind Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione T, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DH, Janeck AS, Tallman K. A cognitive-behavioral group for patients with various anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1205–1211. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Palmer RL. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:311–319. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnotic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins ER, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621–632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, Rucci P. Reliability of the self-report version of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;15:183–185. doi: 10.1002/da.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Lui J, Swartz M, Blazer DG. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;168:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen HU, Ustan TB, Roy-Byrne PP, Walters EE. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:801–808. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur R, Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Leger E, Gagnon F, Thibodeau N. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(6):957–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Harvey A, Watkins E, Shafran R. Conceptual foundations of the transdiagnostic approach to CBT. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Connolly J, Hallam RS. The psychiatric nurse as therapist. British Medical Journal. 1973;2:156–160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5872.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia, scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P. Effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for diagnostically heterogenous groups: A benchmarking study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:344–350. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P, Norton PJ. Efficacy of transdiagnostic treatments: A review of published outcome studies and future directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Barlow DH. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological interventions: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist. 2010;65(2):73–84. doi: 10.1037/a0018121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified treatment approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JM. The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.2 [Computer software] Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ. An open trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hope DA. Preliminary evaluation of a broad-spectrum cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2005;36:79–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Philipp LM. Transdiagnostic approaches to the treatment of anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2008;45:214–226. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Price EC. A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across anxiety disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:521–531. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253843.70149.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. An open trial of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13(4):166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer RA, Ranieri WF, Beck AT, Clark DA. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1993;7:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez L, Bennett S, Goldstein C, Barlow DH. Understanding anxiety disorders from a “triple vulnerabilities” framework. In: Antony MM, Stein MB, editors. Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Hannan SE, Worhunsky P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication nonresponders with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A wait-list-controlled open trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:922–931. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer PJ. Classification of neurosis. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Arkowitz H, Dozois DJA. Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozois DJA. Preparing clients for cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–747. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800320058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods MD, Sholomskas DE, Shear MK, Gorman JM, Barlow DH, Goddard AW, Cohen J. Efficient allocation of patients to treatment cells in clinical trials with more than two treatment conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1446–1448. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]