Abstract

Purpose

Cancer treatments are complex, involving multiple clinicians, toxic therapies, and uncertain outcomes. Consequently, patients are vulnerable when breakdowns in care occur. This study explored cancer patients' perceptions of preventable, harmful events; the impact of these events; and interactions with clinicians after such events.

Patients and Methods

In-depth telephone interviews were conducted with cancer patients from three clinical sites. Patients were eligible if they believed: something “went wrong” during their cancer care; the event could have been prevented; and the event caused, or could have caused, significant harm. Interviews focused on patients' perceptions of the event, its impact, and clinicians' responses to the event.

Results

Ninety-three of 416 patients queried believed something had gone wrong in their care that was preventable and caused or could have caused harm. Seventy-eight patients completed interviews. Of those interviewed, 28% described a problem with medical care, such as a delay in diagnosis or treatment; 47% described a communication problem, including problems with information exchange or manner; and 24% described problems with both medical care and communication. Perceived harms included physical and emotional harm, disruption of life, effect on family members, damaged physician-patient relationship, and financial expense. Few clinicians initiated discussion of the problematic events. Most patients did not formally report their concerns.

Conclusion

Cancer patients who believe they experienced a preventable, harmful event during their cancer diagnosis or care often do not formally report their concerns. Systems are needed to encourage patients to report such events and to help physicians and health care systems respond effectively.

INTRODUCTION

Effective communication between patients and clinicians can prevent lapses in quality and, when problems occur, can mitigate harm and restore trust. Patient-centered communication is especially important in cancer care.1–2 Cancer is typified by emotional and physical challenges. Treatments are complex, involving multiple clinicians, toxic therapies, and uncertain outcomes. Unfortunately, communication with patients with cancer is often not ideal.3–6 Patients frequently leave medical visits overwhelmed, with unmet expectations, confusion about treatment plans, and uncertainties about whom to contact with questions, all of which increases the likelihood that their quality of care will be compromised.7–8

Skillful communication is equally important after a breakdown in care.9 Hospital accreditation standards and some state laws require that patients be informed about all outcomes of care, including unanticipated outcomes.10–11 Yet research suggests that communication with patients and families after care has gone wrong is lacking, compounding patients' and families' suffering.12–16

Improving communication with patients with cancer requires a better understanding of patients' experiences of breakdowns in care. Existing metrics provide limited insight into patients' perceptions of problems during care. Therefore, we conducted in-depth interviews with patients who had recently undergone cancer treatment and who believed that something had gone wrong during their care. Studying communication around care breakdowns in the complex setting of cancer care can suggest ways of making patient care more patient-centered throughout the health care system.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Setting and Sample Selection

This study was conducted in the Cancer Communication Research Center, which is affiliated with the Cancer Research Network. These National Cancer Institute–funded projects involve a consortium of research organizations affiliated with integrated health care delivery systems. Three Health Maintenance Organization Cancer Research Network sites located in Washington, Massachusetts, and Georgia recruited participants for this study. Potentially eligible study participants included patients who had completed treatment for stage I-III breast cancer (women only) or stage I-III gastrointestinal cancer (men and women) 6 to 18 months before the study period. All patients were 21 to 80 years old. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each site.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Potential participants identified through their electronic medical records were invited to participate via mail. Patients who did not opt out were contacted by telephone approximately 2 weeks after the original letter was mailed. Those who expressed interest were screened to determine eligibility. To be eligible for the study, patients had to identify that something “went wrong” during their cancer care; what went wrong was preventable, and what went wrong caused, or could have caused, significant harm. Harm included psychological and physical harm, as well as other negative consequences. Events meeting these three criteria are hereafter referred to as problematic events.

Interview Protocol and Content

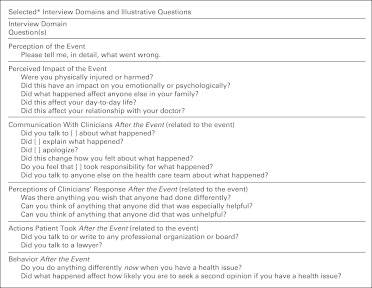

Two experienced interviewers conducted telephone interviews. Patients were asked to describe the problematic events they experienced, the impact of the events, their communication with clinicians before and subsequent to the events, and clinicians' actions afterward (Fig 1). Most questions were open-ended; interviewers probed for elaboration or clarification. Interviews lasted approximately one hour; participants received $25. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Fig 1.

Selected interview domains and illustrative questions. (*) Domains and questions represent a sample of all questions asked. A complete interview guide is available upon request from K.M.M.

Data Analysis

Interview transcripts were coded using directed content analysis.17–18 Coding categories were created using interview domains and were refined through an iterative process of transcript review, coding, and discussion, until consensus was reached. Four coders independently coded the same three transcripts and discussed discrepancies until agreement of at least 85% was reached. The remaining transcripts were assigned to coders, with 12 transcripts coded by at least two coders to ensure continuing consistency (ie, agreement greater than 85%). Transcripts and codes were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 17.0, Chicago, IL) to facilitate manipulation and summarization. Frequency counts were generated to summarize results.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

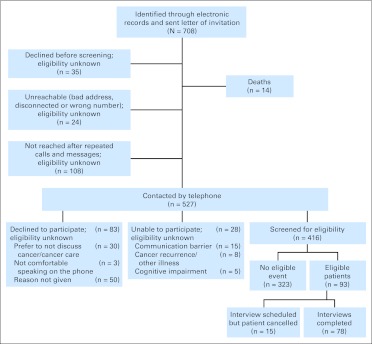

A total of 708 patients (breast cancer, n = 539; gastrointestinal cancer, n = 169) were identified through electronic records and invitation letters (Fig 2). Of these, 35 patients opted out before follow-up contact. Of the remaining 673, 527 patients were contacted; 416 patients expressed interest in participating, 323 patients did not identify any problematic events during their care, and 93 patients responded affirmatively to the three screening questions. Of the 93 patients who identified an eligible problematic event, 78 patients completed in-depth interviews. Interviewee characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Interviewees were asked all questions (Fig 1), unless an earlier response obviated the need for a question. All percentages reported were calculated using the total number of interviewees (n = 78) as the denominator, unless otherwise noted.

Fig 2.

Summary of patient selection and recruitment process.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n = 78)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| No. of women | 75 | 96.2 |

| Age, years | ||

| 21-44 | 9 | 11.5 |

| 45-59 | 36 | 46.2 |

| ≥ 60 | 33 | 42.3 |

| Race | ||

| White | 55 | 70.5 |

| African American | 18 | 23.1 |

| Asian | 2 | 2.6 |

| Native American | 1 | 1.3 |

| Multiracial/other | 2 | 2.6 |

| Hispanic | ||

| Yes | 1 | 1.3 |

| First language | ||

| English | 74 | 94.9 |

| Level of education completed | ||

| High school or less | 13 | 16.7 |

| Some college | 21 | 26.9 |

| 4-year college degree | 18 | 23.1 |

| Beyond 4-year college degree | 26 | 33.3 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 70 | 89.7 |

| Gastrointestinal | 8 | 10.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 47 | 60.3 |

| Divorced/separated | 19 | 24.4 |

| Widowed | 6 | 7.7 |

| Single | 6 | 7.7 |

| Working status | ||

| Full-time | 37 | 47.4 |

| Retired | 22 | 28.2 |

| Not working/unemployed | 10 | 12.8 |

| Part-time | 8 | 10.3 |

| Disabled | 1 | 1.3 |

| Ever worked in health care setting? | ||

| Yes | 30 | 38.5 |

Patients' Perceptions of Problematic Events

Problematic events were reported by 93 (13%) of 708 patients who had recently been treated for breast or gastrointestinal cancer (22% of 416 patients screened). In-depth interviews with the 78 participants allowed us to categorize the events into three groups. Twenty-eight percent of patients interviewed believed something had gone wrong during their medical care; most commonly, patients perceived delays in diagnosis and/or treatment of cancer. Other problematic events included surgical problems requiring additional surgery, infections delaying recovery, and prolonged complications from treatment.

Forty-seven percent of patients interviewed believed something had gone wrong in communication, without a breakdown in their medical care. Communication breakdowns involved problems with information exchange, including insufficient information provided to the patient (eg, not being told about treatment options), inaccurate information provided to the patient (eg, patient was told her cancer was life-limiting, but test results revealed it was treatable), and the clinician not listening to the patient (eg, dismissing reports of symptoms). Also included were reports that the clinician (or another person in the health care system) was cold or uncaring.

Twenty-four percent of patients interviewed described co-occurring breakdowns in both medical care and communication, such as perceived delays in diagnosis and treatment, with poor information exchange exacerbating the delay. Other examples included infections and postsurgery complications that the patient believed were exacerbated by the clinician's unresponsiveness to the patient's reports of problems and insufficient information provided to the patient that the patient believed impaired their clinical decision-making and led to worsened pain.

Perceived Impact of the Problematic Event

Patients reported a variety of consequences of the problematic events (Table 2). Most patients (20 of 22 patients; 91%) who reported a breakdown in medical care believed they had experienced physical harm, such as pain, need for additional treatment or hospitalization, delayed recovery, progression of cancer, or infection. Thirty percent (11 of 37) of those patients who experienced a communication breakdown without a concomitant breakdown in medical care believed they had been physically harmed. For example, some patients believed they were given insufficient information about how to prepare for chemotherapy and therefore experienced serious adverse effects that could have been mitigated. All patients describing a communication breakdown (either by itself or concomitant with a breakdown in medical care) reported emotional or psychological consequences, as did most patients who experienced a breakdown in medical care. Patients reported feelings of anger, fear, distress, frustration, anxiety, depression, and sadness.

Table 2.

Patient Perception of Harm Attributed to Problematic Event by Event Type

| Perceived Harm | All Participants (n = 78) |

Breakdown in Medical Care Only (n = 22) |

Breakdown in Communication Only (n = 37) |

Breakdown in Medical Care and Communication (n = 19) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |

| Physical harm | 45 | 57.7 | 20 | 90.9 | 11 | 29.7 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Psychological or emotional harm | 75 | 96.2 | 19 | 86.4 | 37 | 100 | 19 | 100 |

| Life disruption | 30 | 38.5 | 11 | 50 | 11 | 29.7 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Negative impact on family | 45 | 57.7 | 17 | 77.3 | 14 | 37.8 | 14 | 73.7 |

| Damaged relationship with provider | 41 | 52.6 | 12 | 54.5 | 18 | 48.6 | 11 | 57.9 |

| Uncompensated financial costs | 29 | 37.2 | 14 | 63.6 | 8 | 21.6 | 7 | 36.8 |

NOTE. Patients could report more than one type of perceived harm.

Fifty-three percent of all patients interviewed indicated their relationship with their clinician was damaged after the event. Several did not see the clinician involved again. In some cases this was because care from that clinician was no longer required, but other patients (30%) deliberately sought care from a different clinician. Some patients (33%) expressed strong feelings about never returning to a particular clinician or clinical site because of the problematic event.

Other consequences of the problematic events included 39% of patients reporting life disruptions (eg, lost work, inability to participate in activities), 37% reporting financial consequences (eg, copayments, lost income), and 58% reporting effects on family members, such as emotional distress or anger.

Responsibility for the Event

A majority of patients (65%) interviewed held one or more physicians fully or partially responsible for the problematic event; fewer (14%) considered a nurse fully or partially responsible. Some patients (23%) viewed other personnel as responsible; whereas 13% did not ascribe responsibility to any one person, viewing the event as attributable to problems with the system. A few patients (13%) ascribed partial responsibility to themselves, for instance by accepting a noncancer diagnosis despite continuing symptoms or by neglecting screening.

Communication With Clinicians After the Event

Overall, 36% of patients reported that they had discussed the problematic event with one or more of those they perceived to be responsible. According to patients, the responsible individual seldom initiated discussions of the problematic event (6%); more often the patient or family member initiated the discussion (27%). Sixty-eight percent of patients reported discussing the problematic event with someone in the health care system other than the person they considered responsible.

In only one instance did the patient feel that the person responsible for the breakdown had assumed responsibility for the event. Slightly more interviewees (8%) reported that someone whom they did not see as directly responsible had assumed responsibility. Nine percent of interviewees were uncertain whether anyone took responsibility. More often, patients reported that no one took responsibility (42% of interviewees). For some patients, discussions about responsibility were not expected, either because they did not ascribe responsibility to a single person (13% of interviewees), the person responsible was never encountered again (23%), or the patient did bring up the event (8%).

Six percent of patients reported receiving a clear explanation of what had occurred. More than half of those (53%) reported the explanation was confusing or incomplete. A few patients (6%) suspected details were withheld and that clinicians were worried about being sued for malpractice. None of the 41 patients who perceived a breakdown in medical care (either by itself or concomitant with a breakdown in communication) reported that anyone in the health care system told them of efforts to prevent recurrences, though three of 37 patients (8%) who had experienced a communication breakdown only reported being told of such efforts. Relatively few patients (12%) reported receiving an apology from the person they perceived as being responsible for the error; slightly more patients (15%) reported receiving an apology from someone else.

Clinicians' Actions After the Event

Fifty-one percent of patients reported that one or more clinicians undertook helpful actions after the event. Among those patients who believed that they had experienced a breakdown in medical care, concomitant with or without a breakdown in communication, nine (22%) of 41 patients reported that someone had taken action to mitigate harm or remedy the error. Some patients (28%) reported that health care personnel had responded in a way that was not helpful, including denying the perceived problem, being defensive, or dismissing the patient's concerns.

Patients' Actions After the Event

A few patients (13%) formally reported their problematic events, by writing a letter, speaking with someone in administration, or completing satisfaction surveys. One patient contacted a professional organization and another contacted a lawyer. Patients' reasons for not formally reporting the problematic events included wanting to focus on their own health, put the event behind them, or focus on the future (28%); believing that reporting the event would not do any good (12%); believing the injury or error was fixed or not significant (6%); uncertainty about who was responsible for the event (5%); and concerns about the impact on the clinician involved (3%). Few patients (3%) wanted financial reparations. Some patients (13%) who had not reported the event or taken other actions subsequently wished that they had or were considering taking action at the time of the interview, specifically, consulting with a lawyer about the event (3%), writing a letter of complaint (3%), voicing their concerns (3%), or obtaining their medical records (3%).

Almost all patients (90%) reported making changes in their health care–related behavior as a result of the problematic event. Reported changes included becoming more proactive during encounters with clinicians by asking more questions about their condition and care (60%); becoming more likely to seek a second opinion (42%); researching symptoms or treatments (36%); being more assertive in interactions with clinicians and the health care system (21%); being more likely to change physicians (12%); paying more attention to physicians' advice (10%); taking more precautions (8%); becoming more likely to seek medical care (5%); and bringing a companion to medical appointments (4%). Some patients (10%) reported becoming more hesitant to seek care as a result of their experience.

DISCUSSION

The last decade has seen a renewed emphasis on patient-centered health care. Nowhere has this focus been more apparent and important than in cancer care.1 The success of these efforts relies partly on understanding the problems that patients with cancer experience. We sought to gain this understanding by interviewing patients with cancer who believed they had experienced significant problems in their care. More than one in five of the cancer patients screened believed that something had gone wrong in their care that was preventable and caused, or could have caused, harm. Most of these patients did not formally report their problematic events. Because our sample consisted primarily of women treated for breast cancer, we cannot generalize about the prevalence of such perceptions in the general population of patients with cancer. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that greater attention to the experiences of patients with cancer and problems with their care is warranted.

Of the patients interviewed, more than half believed that a breakdown in medical care had occurred, most commonly there was a perceived delay in diagnosis or treatment. These patients may have been mistaken about the perceived errors, but because many patients did not express their concerns, their clinicians could not correct misperceptions or provide reassurance. Patients also identified problematic events that were not traditional adverse events or medical errors, but rather communication breakdowns, similar to breakdowns described by other studies.6,19–23 These communication breakdowns represented fundamental problems in information sharing, care coordination, and emotional support and were sometimes reported to be as harmful from the patients' perspective as traditional adverse events or medical errors. These patient-reported problems in communication and medical care represent meaningful quality measures in their own right.

Currently, most of the systems in place to detect problems in care rely on the patient alerting the institution, such as in filing a complaint. However, only a small subset of patients in this study formally reported what had occurred, and many preferred to focus their limited energy on getting well. Patient complaints contain important information, including clinicians' likelihood of being sued for malpractice. For Medicare patients, these complaints require a formal written response.24 In addition, while health care systems routinely survey patients regarding satisfaction with their care, such surveys are unlikely to capture the majority of patients' concerns with care, as evidenced by the small number in this study who reported responding to such surveys. However, many of the patients in our study spoke with a physician or nurse about what had occurred, indicating that patients are willing to share their experiences.

New approaches are needed to increase health systems' awareness of patients' perceptions of care problems and facilitate effective responses. Active surveillance systems that regularly reach out to patients and inquire about their symptoms are being developed to measure patient-reported outcomes in oncology and other diseases.25–29 In addition, Internet-based reporting mechanisms, including patient portals, are being created so that patients can report adverse events and errors.30 Such systems should be expanded to facilitate patient reports of care breakdowns. Patients should be able to choose who in the health system receives the report and whether the report is shared with their health care team. They should be able to provide both positive and negative feedback. Health care systems should educate patients about the availability of these reporting systems, and emphasize their eagerness to hear from patients. Patients' reports reflect their perceptions of events, which may differ from clinicians' perceptions of what might have occurred, but patients' reports are important nonetheless and may predict their subsequent actions.31 The success of such reporting systems will ultimately rest on the ability of health plans to respond meaningfully to patient reports.

Few patients viewed their problematic events as attributable to multiple clinicians or systemic flaws, which contrasts with the patient safety movement's emphasis on the role that system breakdowns play in care problems. Health systems should help patients understand the complexity of cancer care delivery and recognize that many patients need identifiable individuals within the system to be responsive to their perceived breakdowns in care.

Despite increased attention to disclosure and apology following adverse events and care breakdowns, open communication remains the exception. Several major organizations have issued guidelines for developing effective disclosure programs.32–33 However, the majority of our patients reported that no clinician disclosed the care breakdown to them, took responsibility, or apologized. Failed or nonexistent disclosures compound patients' suffering.34 The absence of disclosures did not mean that patients were unaware that problems had occurred, but rather reinforced patients' perception that their clinicians did not care about what happened. In some instances, the clinician might have been unaware of the patient's concerns or desire for the clinician to respond. Nonetheless, clinicians are still responsible for creating an environment in which patients are encouraged to share any concerns about problematic events.

This study has limitations. The patients who participated may differ in beliefs, attitudes, and experiences from those who declined. A second potential concern of our study is sample size. Seventy-eight is a large number of in-depth interviews, but would be considered small for a large-scale survey. Participating patients were predominantly women who had been treated for breast cancer. Interviews with male patients and patients with other types of cancer are needed. In addition, because all interviewees reported either physical or emotional harm from the events, patients who experienced a near miss but were not distressed by it are not represented. Two of the participating sites are integrated delivery systems that provide both care and coverage to members and the third is a mixed model that provides care to health maintenance organization members and patients with other forms of insurance. This may have limited the extent to which our findings are generalizable to patients in other care settings and to uninsured patients. Finally, because our interest was in understanding patients' perceptions, we focused on patient-identified events and did not seek to compare patients' reports with clinical records. This approach allowed us to explore events that would not have been captured in clinical records, but also prevented us from assessing whether patients' perceptions were consistent with clinicians' perceptions of care problems.

These findings suggest that patient-perceived problematic events in cancer care may be relatively common, physically and emotionally harmful, and often are not formally reported. As health care institutions strive to develop patient-centered cultures of care, additional consideration should be given to how improved communication with patients could prevent problems in care, as well as to what systems would encourage patients to alert their clinicians to perceived problems in care and facilitate an effective response.

Footnotes

See accompanying editorial on page 1744

Supported by Grant No. P20CA137219 from The National Cancer Institute.

Presented in part at the European Association for Communication in Healthcare International Conference on Communication in Healthcare, Verona, Italy, September 5-8, 2010, and at the Health Maintenance Organization Research Network Annual Meeting, Austin, TX, March 21-24, 2010.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Thomas H. Gallagher, CRICO/RMF Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kathleen M. Mazor, Douglas W. Roblin, Sarah M. Greene, Carolyn D. Prouty, Thomas H. Gallagher

Financial support: Kathleen M. Mazor, Thomas H. Gallagher

Administrative support: Kathleen M. Mazor, Cassandra L. Firneno, Carolyn D. Prouty, Thomas H. Gallagher

Provision of study materials or patients: Kathleen M. Mazor, Douglas W. Roblin, Josephine Calvi

Collection and assembly of data: Kathleen M. Mazor, Douglas W. Roblin, Sarah M. Greene, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra L. Firneno, Josephine Calvi

Data analysis and interpretation: Kathleen M. Mazor, Douglas W. Roblin, Sarah M. Greene, Celeste A. Lemay, Cassandra L. Firneno, Carolyn D. Prouty, Kathryn Horner, Thomas H. Gallagher

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein R, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:755–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surbone A. Telling the truth to patients with cancer: What is the truth? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:944–950. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70941-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surbone A. Persisting differences in truth telling throughout the world. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:143–146. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teno JM, Lima JC, Lyons KD. Cancer patient assessment and reports of excellence: Reliability and validity of advanced cancer patient perceptions of the quality of care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1621–1626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6576–6586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiello Bowles EJ, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, et al. Understanding high-quality cancer care: A summary of expert perspectives. Cancer. 2008;112:934–942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner EH, Aiello Bowles EJ, Greene SM, et al. The quality of cancer patient experience: Perspectives of patients, family members, providers and experts. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:484–489. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher TH. A 62-year-old woman with skin cancer who experienced wrong-site surgery: Review of medical error. JAMA. 2009;302:669–677. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Joint Commission: Hospital Accreditation Standards, 2007. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mastroianni AC, Mello MM, Sommer S, et al. The flaws in state ‘apology' and ‘disclosure' laws dilute their intended impact on malpractice suits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1611–1619. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, et al. Patients' and physicians' attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289:1001–1007. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iedema R, Sorensen R, Manias E, et al. Patients' and family members' experiences of open disclosure following adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:421–432. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazor K, Goff S, Dodd K, et al. Understanding patients' perceptions of medical errors. J Commun Healthcare. 2009;2:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazor KM, Goff SL, Dodd KS, et al. Parents' perceptions of medical errors. J Patient Saf. 2010;6:102–107. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181ddfcd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weingart SN, Price J, Duncombe D, et al. Patient-reported safety and quality of care in outpatient oncology. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Averbeck BM, et al. Can patient safety be measured by surveys of patient experiences? Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2008;34:266–274. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garbutt J, Bose D, McCawley BA, et al. Soliciting patient complaints to improve performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor BB, Marcantonio ER, Pagovich O, et al. Do medical inpatients who report poor service quality experience more adverse events and medical errors? Med Care. 2008;46:224–228. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. Patient-reported service quality on a medicine unit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:95–101. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287:2951–2957. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.22.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abernethy AP, Herndon JE, 2nd, Wheeler JL, et al. Improving health care efficiency and quality using tablet personal computers to collect research-quality, patient-reported data. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1975–1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abernethy AP, Wheeler JL, Zafar SY. Management of gastrointestinal symptoms in advanced cancer patients: The rapid learning cancer clinic model. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4:36–45. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32833575fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crane HM, Lober W, Webster E, et al. Routine collection of patient-reported outcomes in an HIV clinic setting: The first 100 patients. Curr HIV Res. 2007;5:109–118. doi: 10.2174/157016207779316369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch E, Iasonos A, Barz A, et al. Long-term toxicity monitoring via electronic patient-reported outcomes in patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5374–5380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder CF, Jensen R, Courtin SO, et al. Patient viewpoint: A website for patient-reported outcomes assessment. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:793–800. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9497-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basch E, Artz D, Iasonos A, et al. Evaluation of an online platform for cancer patient self-reporting of chemotherapy toxicities. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:264–268. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu AW, Huang IC, Stokes S, et al. Disclosing medical errors to patients: It's not what you say, it's what they hear. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1012–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Quality Forum: Safe Practices for Better Healthcare, 2009 Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conway J, Federico F, Stewart K, et al. Respectful Management of Serious Clinical Adverse Events [IHI Innovation Series white paper] Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Truog RD, Browning DM, Johnson JA, et al. Talking With Patients and Families About Medical Error. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]