Abstract

This report concerns nanofiber composites that incorporate N-heterocyclic carbenes and the use of such composites for testing antimicrobial and antifungal activities. The nanofiber composites were produced by electrospinning mixtures of the gold chloride or gold acetate complexes of a bis(imino)acenaphthene (BIAN)-supported NHC with aqueous solutions of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The products were characterized by scanning-electron microscopy, which revealed that nanofibers in the range of 250–300 nm had been produced. The biological activities of the nanofiber composites were tested against two Gram-positive bacteria, six Gram-negative bacteria, and two fungal strains. No activity was evident against the fungal strains. However, the gold chloride complex was found to be active against all the Gram-positive pathogens and one of the Gram-negative pathogens. It was also found that the activity of the produced nanofibers was localized and that no release of the bioactive compound from the nanofibers was evident. The demonstrated antimicrobial activities of these novel nanofiber composites render them potentially useful as wound dressings.

Keywords: nanofiber, electrospinning, N-Heterocyclic carbene, biopolymer, antimicrobial

Introduction

The production of nanofibers via the electrospinning process has recently attracted significant attention.1 Nanofibers have applications in many fields, including optoelectronics, sensor technology, catalysis, tissue engineering, and medicine.2,3 The electrospinning process begins with a polymer solution that is loaded into a syringe and subsequently subjected to an applied electric field. When the repulsive electrical forces overcome the surface tension of the solution droplet, a charged jet of solution is ejected from the tip of the syringe towards an oppositely charged collector. The solvent evaporates from this jet, thereby depositing a nanofiber mat on the collector.2

Electrospun fibers have been studied extensively for their high surface area-to-volume ratios, small pore sizes, high porosities, and their ability to incorporate a variety of bioactive compounds, thus making them particularly attractive materials for wound dressings.4 A variety of bioactive molecules, including antiseptics, antibiotics, and antifungals have been incorporated into nanofibers and used in this context.5

Electrospun fibers of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) represent attractive, inexpensive scaffolds for the support of bioactive molecules.6 PVA has been used for wound dressings, contact lens fabrication, and drug delivery systems due to its water solubility, biocompatibility, and long-term stability.7–10

We have previously investigated the antimicrobial activities of gold(I) complexes of N-heterocyclic carbenes supported by a bis(imino)acenaphthene (BIAN) ligand.11 The BIAN class of the ligand, which features the fusion of a naphthalene moiety to a diimine, has a number of interesting and distinctive properties.12 One such property is its extensive redox behavior, which could be useful to control metal release from, eg, antimicrobials and anticancer drugs.11 To the best of our knowledge, the only prior work in this general area focuses on the use of silver(I)-imidazole cyclophane gem-diol complexes encapsulated by electrospun Tecophilic nanofibers.13 The resulting nanofiber mats were found to be effective against Staphylococcus aureus and comparable to 0.5% AgNO3. The fiber mats also showed antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus, Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, and Saccharomyces cervisiae.

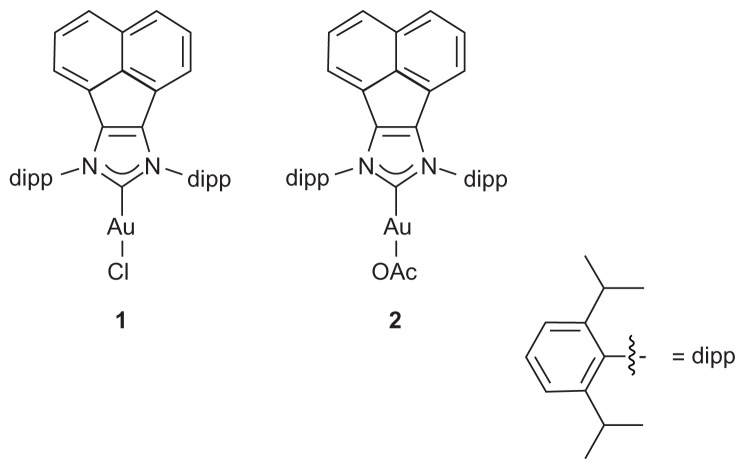

This study explores the antimicrobial and antifungal activities of nanofibers produced by electrospinning two N-heterocyclic carbene gold(I) complexes (Figure 1) with PVA.

Figure 1.

(1) N-heterocyclic carbene gold chloride and (2) gold acetate complexes.

Materials and methods

NHC preparation

Compounds 114 and 211 were synthesized according to the literature procedures.

Nanofiber preparation

Hydrolyzed (99%) PVA granules with an average molecular weight of 130,000 were purchased from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI). The preparation of the electrospun fibers, which incorporated compounds 1 and 2, was accomplished by electrospinning aqueous solutions of 5% w/v PVA and either compound 1 or 2 in a final concentration of 1 mg/mL in PVA at a potential of 20 kV. The electrospinning apparatus comprised a hypodermic syringe, a graphite electrode, an aluminum collecting drum, and a high voltage supply. A high flow rate of 0.7 mL/hour was maintained by connecting a syringe pump to the hypodermic syringe.

Microorganisms

The microbial organisms used in this study included the Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus NRRL B-313 and Bacillus subtilis NRRL B-543, and the Gram-negative bacteria Salmonella typhi, E. coli JM DSM 3949, Pseudomonas auroginosa, Enterobacter faecalis, Proteus vulgaris, and Micrococcus leuteus. The fungal strains, S. cervisiae BY 4741 and C. albicans NRRL Y-477, were also examined.

Antimicrobial activity assays

The antimicrobial activity toward each microbial organism was evaluated in a 1 millimolar aqueous solution of the microorganism using the modified agar diffusion technique.15 The standard antibiotic sensitivity discs, tetracycline, erythromycin, and cephazolin, at a concentration of 15 μg/disc were used for comparison with the activities of 1 and 2. The tested bacterial and fungal strains were sustained on nutrient agar in ISP-2 media at 37°C and 26°C, respectively. Prior to each assay, the various strains were cultivated in the appropriate broth media for at least 12 hours using a reciprocal shaker operating at 150 rpm. Samples of 1 mL were withdrawn each hour and the growth rate was determined by measuring the optical densities of the growing cells versus that of the growth medium at a wavelength of 623 nm. When the growth rate reached the exponential phase, the cells were used to inoculate the agar media, thereby achieving a cell concentration of 0.015/mL. Next, the medium was poured onto 9 mm agar plates, thus forming agar layers of 3.5–4.5 mm. After solidification, wells of 10 mm in diameter were cut in the agar plates using a sterile cork borer, and 0.1 mL of the stock solution was poured into each well. The agar plates were then incubated at 4°C for 1 hour to ensure that diffusion of the tested compounds had ocurred. Following this, the bacterial and fungal strains were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 26°C, respectively. The diameter of each resulting inhibition zone was measured following incubation.

Assays of the antimicrobial activities of the impregnated nanofibers

The agar plates were prepared and inoculated with the test strains as described above. Following this, the newly prepared nanofibers were cut into rectangles of 1 × 2 cm, after which they were placed carefully on top of the agar plates with the aid of sterile forceps. The plates were then incubated at 4°C for 1 hour to ensure that diffusion of the tested compounds had ocurred. Subsequently, the plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 26°C for the bacterial and fungal strains, respectively. Following incubation, the nanofibers were partially removed by means of sterile forceps and the area of each plate was investigated for localized antibacterial activity.

Results

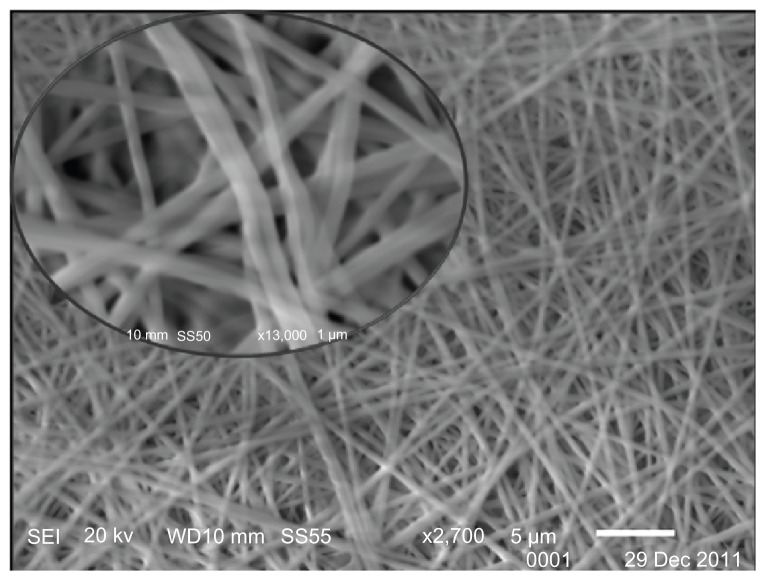

Figure 2 displays a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the electrospun nanofiber composite incorporating compound 1. The nanofibers were formed from a mixture of 1 mg/mL of compound 1 and 5% w/v PVA. The nanofibers produced from the 1/PVA solution consisted of homogeneous, even nanofibrous mats with diameters that ranged between 250 and 300 nm. No granules were evident on the fibers.

Figure 2.

SEM micrograph of compound 1/PVA nanofibers.

Note: Inset: magnification 2700×, 13,000×.

Antimicrobial activities of the tested compounds

Examination of the agar plates revealed that only nanofibers containing the N-heterocyclic carbene complex 1 exhibit antimicrobial activity. The inhibition zones for the Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and B. subtilis were found to be 19 ± 1 and 16 ± 1 mm, respectively. Of the six Gram-negative bacterial strains, only M. leuteus was effective and exhibited an inhibition zone of 24 ± 1 mm, which is higher than those for B. subtilis and S. aureus. By contrast, nanofibers that incorporated compound 2 showed no activity with respect to the tested microorganisms. Neither compound displayed activity against the two fungal strains. The standard antibiotics, tetracycline, erythromycin, and cephazolin were also tested and the inhibition zones were found to be 17 ± 1, 26 ± 1, and 18 ± 1 mm for S. aureus, and 12 ± 1, 26 ± 1, and 11 ± 1 mm for B. subtilis, respectively. The inhibition zones reported for the Gram-negative M. leuteus were 17 ± 1, 34 ± 1, and 12 ± 1 mm, respectively. Accordingly, the activity of the new nanofiber composite is of comparable potency to those of the standard antibiotics.

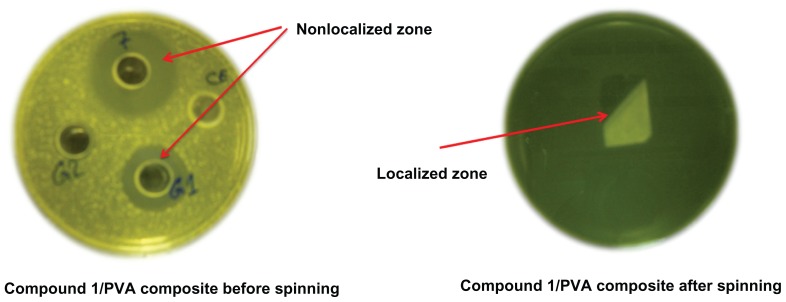

Localization of the antimicrobial effect of the prepared nanofibers

Figure 3 shows the local environment produced as a result of using the electrospinning technique for nanofiber production (right) compared to the unloaded, solution-phase material that diffuses through the agar plate (left). The plates were cultivated with M. leuteus and the measurements were made after 1 and 5 days. The product was re-examined after four weeks in order to check that compound 1 had not been released from the nanofibers. No release of the bioactive compound from the fiber was detected after the four-week period, as confirmed by comparison of the nonlocalized zone (Figure 3, left) with the localized zone (Figure 3, right). In the nonlocalized system, compound 1 was found to diffuse easily through the agar, as evidenced by the antimicrobial activity outside the treated area. By contrast, the localized system results from the loading of compound 1 into the nanofibers, and the antimicrobial effect was detectable only below the fibers and did not spread outside the treated area. This confirms the ability of the new nanofibers to hold and entrap compound 1. Therefore, the localized activity of the new nanofiber composite represents a significant advantage with respect to the unloaded solution phase mixture.

Figure 3.

Antibacterial assays of compound 1/PVA composite before and after electrospinning.

Conclusion

The incorporation of two BIAN-supported N-heterocyclic carbene gold complexes into nanofibers was successful. Nanofibers containing the gold(I) chloride complex 1 exhibit localized activity against both of the Gram-positive and one of the Gram-negative strains tested. Moreover, the activity of the nanofiber composite described herein is comparable to those of standard antibiotics. None of the complexes exhibited any antifungal activity.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the King Saud University Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Science Research Center. We also thank the Robert A Welch Foundation, Houston, TX, USA.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Zahedi P, Rezaeian I, Ranaei-Siadat SO, Jafari SH, Supaphol P. A review on wound dressings with an emphasis on electrospun nanofibrous polymeric bandages. Polym Adv Technol. 2010;21:77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doshi J, Reneker DH. Electrospinning process and applications of electrospun fibers. J Electrost. 1995;35:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattarai SR, Bhattarai N, Yi HK, Hwang PH, Cha DI, Kim HY. Novel biodegradable electrospun membrane: scaffold for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2595–2602. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rujitanaroj PO, Pimpha N, Supaphol P. Wound-dressing materials with antibacterial activity from electrospun gelatin fiber mats containing silver nanoparticles. Polymer. 2008;49:4723–4732. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greiner A, Wendorff JH. Electrospinning: A fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:5670–5703. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong KH. Preparation and properties of electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol)/silver fiber web as wound dressings. Polym Eng Sci. 2007;47:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao L, Haas TW, Guiseppi-Elie A, Bowlin GL, Simpson DG, Wnek GE. Electrospinning and stabilization of fully hydrolyzed poly(vinyl alcohol) fibers. Chem Mater. 2003;15:1860–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi M, Gu Y, Sakata N, Kim DH, et al. PVA hydrogel sheet macro-encapsulation for the bioartificial pancreas. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5885–5892. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koyano T, Minoura N, Nagura M, Kobayashi KI. Attachment and growth of cultured fibroblast cells on PVA/chitosan-blended hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39:486–490. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980305)39:3<486::aid-jbm20>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young TH, Hung CH. Change in electrophoretic mobility of PC12 cells after culturing on PVA membranes modified with different diamines. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67:1238–1244. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butorac RR, Al-Deyab SS, Cowley AH. Antimicrobial properties of some bis(iminoacenaphthene) (BIAN)-supported N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of silver and gold. Molecules. 2011;16:2285–2292. doi: 10.3390/molecules16032285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill NJ, Vargas-Baca I, Cowley AH. Recent developments in the coordination chemistry of bis(imino)acenaphthene (BIAN) ligands with s- and p-block elements. Dalton Trans. 2009:240–253. doi: 10.1039/b815079f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melaiye A, Sun Z, Hindi K, et al. Silver(I)-imidazole cyclophane gem-diol complexes encapsulated by electrospun tecophilic nanofibers: Formation of nanosilver particles and antimicrobial activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2285–2291. doi: 10.1021/ja040226s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasudevan KV, Butorac RR, Abernethy CD, Cowley AH. Synthesis and coordination compounds of a bis(imino)acenaphthene (BIAN)- supported N-heterocyclic carbene. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:7401–7408. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00278j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez C, Pauli M, Bazevque P. An antibiotic assay by the agar well diffusion method. Acta Biologiae et Medicine Experimentalis. 1990;15:113–115. [Google Scholar]