Abstract

The transcriptional regulator SnoN plays a fundamental role as a modulator of transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)-induced signal transduction and biological responses. In recent years, novel functions of SnoN have been discovered in both TGFβ-dependent and TGFβ-independent settings in proliferating cells and postmitotic neurons. Accumulating evidence suggests that SnoN plays a dual role as a corepressor or coactivator of TGFβ-induced transcription. Accordingly, SnoN exerts oncogenic or tumor-suppressive effects in epithelial tissues. At the cellular level, SnoN antagonizes or mediates the ability of TGFβ to induce cell cycle arrest in a cell-type specific manner. SnoN also exerts key effects on epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), with implications in cancer biology. Recent studies have expanded SnoN functions to postmitotic neurons, where SnoN orchestrates key aspects of neuronal development in the mammalian brain, from axon growth and branching to neuronal migration and positioning. In this review, we will highlight our understanding of SnoN biology at the crossroads of cancer biology and neurobiology.

Keywords: SnoN, TGFβ-signaling and responses, transcriptional regulator, cancer, axon growth, neuronal migration and positioning

1. Introduction

The Sno gene, encoding the protein SnoN, was identified more than 20 years ago in a study screening for genes related to the oncogene c-ski [1]. The identification of the human Sno gene was followed by isolation of orthologues in vertebrates and invertebrates including mouse, chicken and Drosophila [2–6]. SnoN came to prominence when it was shown to be involved in the regulation of TGFβ signaling and cancer biology [7,8]. Recent studies have revealed that SnoN functions extend beyond cycling cells to postmitotic neurons [9–12]. In this review, we will focus on the versatile functions of SnoN and their underlying mechanisms in TGFβ-dependent and independent signaling, tumorigenesis, and brain development.

Several observations link SnoN’s ability to regulate transcription to its effects on biological responses [13–15]. Not surprisingly, SnoN interacts with transcriptional regulators including the Smads and components of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) complex [7,8,16]. Biochemical and structural studies have defined specific regions, motifs and domains that contribute to SnoN’s interaction with other proteins. SnoN associates with the TGFβ-regulated signaling proteins Smad2 and Smad3 via a region encompassing amino acids 88-92 in SnoN [17]. Smad4 associates with SnoN via the SAND domain, which is approximately 100 amino acids [18]. The SAND domain, located in the N-terminal region of SnoN, is also found in chromatin remodeling proteins including Sp100, AIRE-1, Nucp41/75 and DEAF-1 [18,19]. Although the SAND domain is thought to mediate DNA binding, SnoN’s SAND domain is proposed to promote structural stability rather than DNA binding [18]. N-terminal to the SAND domain is the dac/ski/sno domain in SnoN, which is approximately 100 amino acids long. The ski/sno/dac domain has a globular structure with five β-sheets and four α-helices, and recent crystallography data of this domain reveal a groove with open and closed conformations that may provide a protein interaction platform [20]. SnoN is proposed to interact via its ski/sno/dac domain with the transcriptional co-repressor NCoR, a component of the HDAC complex [16]. The ski/sno/dac domain also contains the motif RxxLxxxxN, which is a recognition motif for the ubiquitin ligase Cdh1-anaphase promoting complex (Cdh1-APC) [21]. The C-terminus of SnoN is characterized by α helical repeats that form a coiled-coil region [22–25]. This region confers SnoN with the ability to form homodimers or heterodimers with Ski [22–26]. Overall, these biochemical studies suggest that distinct regions within SnoN mediate associations with different proteins that play important roles in SnoN-dependent cellular functions.

2. SnoN Functions in Proliferating Cells

Since its identification in the late 80’s, SnoN has been the subject of intense investigation. Several lines of evidence suggest that SnoN plays essential roles in TGFβ-dependent signaling, though SnoN also harbors TGFβ-independent functions.

Ai. SnoN as a complex regulator of TGFβ-induced transcription

SnoN has critical roles in regulating signaling and responses by the TGFβ family of cytokines. TGFβs exerts pleiotropic effects in multicellular organisms that are essential for normal development and homeostasis [27,28]. The Smad signaling pathway represents the canonical mechanism by which TGFβ triggers its biological responses. TGFβ initiates signaling by forming an active heteromeric complex with cell surface type I and type II ser/thr kinase receptors [27,29]. The activated ligand-receptor complex in turn stimulates receptor regulated-Smad2/3 (R-Smad2/3) phosphorylation and association with the common partner Smad4 [30]. The R-Smad2/3-Smad4 complex translocates to the nucleus, binds to specific DNA Smad binding elements (SBE) within TGFβ-responsive genes, and regulates transcription [31–33].

SnoN associates with Smad2/3 and Smad4, and is recruited to TGFβ responsive genes, and thus influences their transcription [7]. When overexpressed, SnoN inhibits transcription of genes regulated by the TGFβ-Smad signaling pathway [7,8]. To relieve SnoN-inhibition of transcription, TGFβ signaling induces the degradation of SnoN protein by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [7,8]. The ubiquitin ligases Cdh1-anaphase promoting complex (Cdh1-APC), Smurf2, and arkadia mediate the ability of TGFβ to induce the ubiquitination and consequent degradation of SnoN [17,34–37]. Remarkably, simultaneously with inducing SnoN degradation, TGFβ stimulates SnoN transcription. Once expressed, SnoN acts as a negative feedback inhibitor of TGFβ signaling [7].

Although the prevailing view holds that SnoN acts as a corepressor with the Smad proteins, several studies have demonstrated that SnoN also acts as a transcriptional coactivator and thus mediates TGFβ-induced transcription in a cell type- and context-dependent manner [12,38,39]. Accordingly, knockdown of SnoN in epithelial cells and primary granule neurons reduces TGFβ-dependent transcription and the expression of TGFβ-responsive genes [12,38,39]. Consistent with this idea, the Drosophila SnoN orthologue, dSno, collaborates with the Drosophila Smad4 orthologue, Medea, to mediate TGFβ responses in the Drosophila nervous system [6]. Thus, the ability of SnoN to facilitate TGFβ-induced transcription and responses is evolutionary conserved. Collectively, these observations suggest that SnoN has dual roles in the regulation of transcription. The nature of SnoN function as a transcriptional corepressor or coactivator may be determined in a cell type- or target gene-specific manner.

What are the cellular consequences of SnoN’s effects on transcription? Paralleling the dual effects of SnoN on TGFβ-induced transcription, SnoN exerts opposing effects on TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest. When overexpressed, SnoN antagonizes TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest [7,17,40]. Consistent with these results, overexpressed SnoN transforms chick embryo fibroblasts [2,22]. However, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and T-lymphocytes deficient in SnoN due to the disruption of one sno allele (sno+/−) have increased rates of proliferation, suggesting that SnoN inhibits cell proliferation [41]. In agreement with these results, SnoN promotes the ability of TGFβ to induce cell cycle arrest [39]. Thus, these data suggest that SnoN mediates TGFβ-induced transcription and cell cycle arrest.

SnoN also regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [42,43]. EMT is a fundamental biological process in which epithelial cells lose apical-basal polarity, cell-cell contact and epithelial markers, undergo cytoskeletal reorganization and mesenchymal differentiation, and become migratory [44,45]. TGFβ is a well-established inducer of EMT, with important consequences in development, wound healing, and cancer progression [46–48]. In view of its significance in development and disease, TGFβ-induced EMT has garnered substantial attention. The non-transformed NMuMG mammary epithelial cells represent a widely used model for studies of TGFβ-induced EMT [49–51]. SnoN strongly suppresses the ability of TGFβ to induce EMT in NMuMG cells as characterized by reduction in TGFβ-induced loss of E-cadherin levels, and acquisition of fibroblastic phenotype [42]. Consistent with these results, SnoN mediates resistance to TGFβ-induced EMT in MDA-MB-231 breast and A549 lung carcinoma cells [43].

Aii. Molecular Mechanisms of SnoN functions in TGFβ signaling

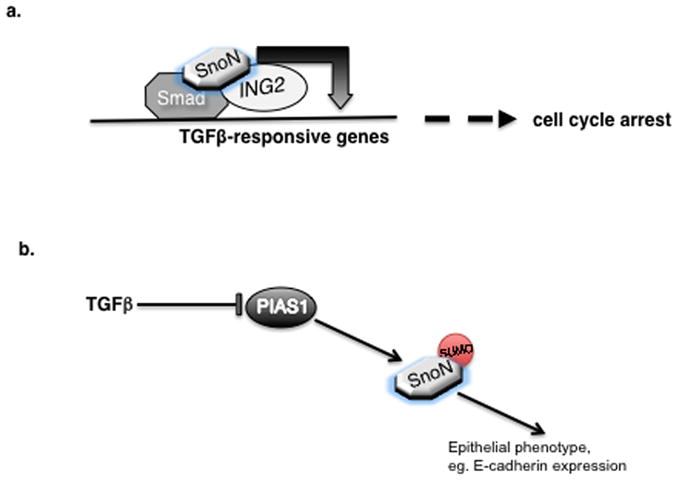

The mechanisms by which SnoN regulates TGFβ-induced transcription have been investigated, though they remain incompletely understood. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how SnoN inhibits TGFβ-induced transcription. SnoN recruits an HDAC transcriptional corepressor complex to TGFβ-responsive genes [13,15]. It has also been proposed that by associating with Smad4, SnoN may disrupt Smad4 interaction with Smad2/3 and consequent gene expression [18]. Although SnoN is predominantly nuclear, it may also localize in the cytoplasm in some cell types [52,53]. Within the cytoplasm, SnoN interacts with the Smads and blocks their nuclear translocation and induction of target gene transcription [52]. The mechanisms by which SnoN mediates TGFβ-induced transcription are also beginning to be characterized. In its capacity as a transcriptional coactivator, SnoN forms a complex with the chromatin remodeling protein ING2, which promotes TGFβ-induced transcription and cell cycle arrest ([38], Figure 1a). ING2 contains a plant homeodomain (PHD) zinc finger that recognizes and binds the Lysine 4 trimethylated motif within histone H3 [54–56]. Interestingly, ING2 interacts via its PHD domain with SnoN [38]. SnoN thus promotes the formation of a Smad2-SnoN-ING2 transcriptional complex (Figure 1a). Accordingly, ING2 and SnoN collaborate to promote TGFβ-induced transcription (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. SnoN functions in TGFβ-induced transcription and cellular responses.

a. SnoN promotes TGFβ-induced transcription and biological responses by acting as an adaptor inducing a Smad-SnoN-ING2 multiprotein complex on promoters of TGFβ-responsive genes. b. Sumoylation is critical for the ability of SnoN to inhibit TGFβ-induced EMT. In epithelial cells, the SUMO E3 ligase PIAS1 sumoylates SnoN and thereby maintains the expression of epithelial markers and phenotype. Activation of TGFβ pathway results in the degradation of PIAS1 and subsequent reduction in the level of sumoylated SnoN, thus facilitating EMT.

As might be anticipated in view of SnoN’s profound effects on the cell cycle and EMT, SnoN is tightly regulated in proliferating cells. SnoN is controlled by ubiquitination and consequent degradation by the proteasome pathway. Several ubiquitin E3 ligases including Cdh1-APC and Smurf2 induce the ubiquitination of SnoN [17,34,37]. In addition to ubiquitination, SnoN is regulated by sumoylation [57,58]. The SUMO E3 ligase PIAS1 promotes the sumoylation of SnoN at Lysine 50 and 383 [57]. Notably, PIAS1 protein is downregulated by TGFβ in cells undergoing EMT ([42], Figure 1b). Consequently, the levels of sumoylated SnoN are decreased dramatically during EMT. Conversely, PIAS1 and sumoylated SnoN inhibit TGFβ-induced EMT ([42], Figure 1b). The expression of wild type PIAS1, but not ligase inactive PIAS1, or the expression of wild type SnoN, but not SUMO loss of function SnoN mutants, suppresses TGFβ-induced EMT. The identification of the PIAS1-SnoN sumoylation pathway as a mechanism that controls TGFβ-induced EMT has raised several questions including how TGFβ regulates the levels of PIAS1 and the mechanisms by which sumoylated SnoN suppresses EMT.

B. TGFβ-independent functions of SnoN

In addition to its role in TGFβ-mediated signaling and responses, the biological functions of SnoN in proliferating cells may involve other signaling pathways. SnoN promotes replicative senescence in MEFs and ovarian epithelial cells [59,60]. Knockin MEFs expressing a Smad-binding defective SnoN protein suggest that SnoN promotes senescence independently of Smad binding [60]. SnoN-induced senescence in MEFs may occur via p53 and PML-dependent mechanisms [60]. However, stable expression of exogenous SnoN in ovarian epithelial cells induces senescence in a p53- and PML-independent manner [59]. Differences in the results of these two studies may be related to cell type and mode of SnoN expression. SnoN may also play a role in estrogen receptor –mediated signaling and responses in a TGFβ-independent setting [61]. SnoN interacts via conserved nuclear receptor binding LxxLL-like motifs with ligand-activated estragon receptor alpha (ERα). SnoN occupies the ER-responsive promoter elements and induces the expression of the ERα target gene thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1) [61]. SnoN associates with the transcriptional coactivator p300 [12,61], and recruits it to ligand-induced ERα [61], leading to activation of transcription.

3. Role of SnoN in Neoplastic Diseases

With functions in cell cycle progression, EMT, and senescence in proliferating cells, SnoN has emerged as a key target in tumorigenesis. Studies over the last several years have revealed that SnoN may have complex roles in cancer.

A. SnoN as an oncogene

SnoN regulation of TGFβ-mediated responses has important implications for how SnoN influences cancer pathology. An important cellular hallmark of cancer is resistance to cytostatic signals [62,63]. The ability of TGFβ to inhibit cell proliferation of distinct cell types including epithelial and hematopoietic cells suggests that the TGFβ-Smad pathway suppresses initiation and early progression of tumorigenesis [64–66]. Accordingly, several types of cancers including mammary, colorectal and pancreatic carcinomas acquire resistance to TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest [64–66]. The ability of overexpressed SnoN to inhibit TGFβ-induced transcription and cell cycle arrest supports a potential role for SnoN in oncogenic transformation of cells. SnoN is upregulated in several types of cancer including melanomas, esophageal and breast carcinomas [43,67-70]. In addition, upregulated SnoN levels correlate with the degree of invasion and poor prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas [71,72]. Several mechanisms including chromosomal amplification and increased protein stability have been proposed to increase SnoN levels in carcinomas [59,71]. SnoN is a relatively short-lived protein and targeted to degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Thus, dysfunction in specific ubiquitin ligases may lead to the accumulation of SnoN protein [59,73]. In summary, at early stages of cancer, increased levels may allow SnoN to act as an oncogene by inhibiting TGFβ-induced transcription and responses.

B. SnoN as a tumor suppressor

Although SnoN is largely characterized as an oncogenic protein, SnoN also operates in a tumor suppressive manner. Heterozygous sno−/+mice develop tumors spontaneously or upon exposure to carcinogenic agents [41]. Consistent with a tumor suppressive role, MEFs, T and B cell lymphocytes derived from sno+/− mice show enhanced rates of proliferation and suppression of apoptosis compared to cells derived from wild type control mice [41].

An important cellular hallmark of cancer is the re-initiation of the process of EMT [44,45]. This program of dedifferentiation is critical for the ability of cancer cells to migrate and form new tumors at distant secondary sites. At the later stages of tumorigenesis, cancer cells utilize the ability of TGFβ to induce EMT to their advantage [48,64,65]. Thus, TGFβ-mediated pathways can act as tumor promoters later in cancer. Inhibition of TGFβ-induced EMT by SnoN suggests the possibility that SnoN may oppose cancer progression. Accordingly, SnoN has been suggested to inhibit tumor invasion at the later stages of cancer [43]. The role of EMT in promoting cancer cell migration raises the possibility that the ability of SnoN to oppose EMT might be dynamically regulated in cancer cells. Reduction in SnoN levels by the ubiquitin pathway or inhibition of SnoN activity could provide the means to promote EMT. The recently identified role of the SUMO E3 ligase PIAS1 and SnoN sumoylation in inhibiting TGFβ-induced EMT raises the important question of whether sumoylation contributes to SnoN antagonism of EMT in cancer cells, and if so, whether downregulation of PIAS1 relieves the negative effect of SnoN sumoylation on EMT and cancer progression. Thus, it will be important to investigate the significance of regulation of the PIAS1-SnoN sumoylation pathway in cancer invasion and metastasis.

The tumor suppressive function of SnoN may also be partly related to participation in TGFβ-independent signaling. Induction of senescence in MEFs by Smad-defective SnoN and involvement of the tumor suppressor p53 and its positive regulator PML in this response suggest that SnoN may cooperate together with p53 and PML to suppress tumorigenesis [60]. SnoN may also induce senescence independently of p53 and PML [59]. Intriguingly, the chromatin remodeling proteins ING1 and ING2 promote senescence in both p53-dependent and independent mechanisms [74–76]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that ING2 may also contribute to the ability of SnoN to induce senescence and hence tumor suppression.

In sum, studies of SnoN in proliferating cells point to complex roles of SnoN in tumor initiation and progression. Different factors including the level of SnoN expression and phase of cancer may contribute to the type of effect that SnoN may have on tumorigenesis. The ability of SnoN to regulate TGFβ-mediated signaling and responses appears to form the basis of many of SnoN’s effects in cancer.

4. SnoN Functions in Postmitotic Neurons

Although SnoN functions have been the subject of intense investigation in proliferating cells and in the context of cancer biology, the expression of SnoN in the mammalian brain has raised the important question of whether SnoN harbors functions in postmitotic neurons. In recent years, novel roles for SnoN in several facets of neuronal development have been uncovered.

A. SnoN as a critical regulator of axon morphogenesis

Much of our current understanding of SnoN function in the nervous system has come from studies of the rodent cerebellar cortex, and in particular cerebellar granule neurons [77,78]. Granule neurons arise from the differentiation of granule cell precursor cells in the external granule layer (EGL) of the developing rodent cerebellum [79–83]. Once generated, granule neurons extend axons that eventually form parallel fibers within the molecular layer of the cerebellar cortex. Along with axon development, the soma of the developing granule neuron migrates inward from the EGL, across the molecular layer, past the Purkinje cell layer, and into the internal granule layer (IGL). Once in the IGL, granule neurons extend dendrites, which undergo growth and branching, pruning, and postsynaptic dendritic differentiation. The features of axon development, migration, and dendrite morphogenesis have been well characterized and widely studied in granule neurons, making these neurons ideal for the molecular mechanisms of neuronal morphogenesis and differentiation in the developing brain [77,84]. Granule neuron development can be studied in vivo, in organotypic cerebellar slices, and in primary culture.

Advances in understanding SnoN function in the nervous system have been gained in the context of axon development (Figure 2a). Knockdown of SnoN in primary granule neurons leads to profound impairment of axon growth [10]. Time-lapse studies in primary granule neurons suggest that SnoN promotes the elongation of axons [10]. Knockdown of SnoN in granule neurons in rat pups, using an in vivo electroporation method designed specifically for the cerebellar cortex, leads to profound loss of parallel fiber axons in the cerebellar cortex [10]. The loss of parallel fiber axons in SnoN knockdown rat pups may result from the inability of axons to elongate or from their destabilization.

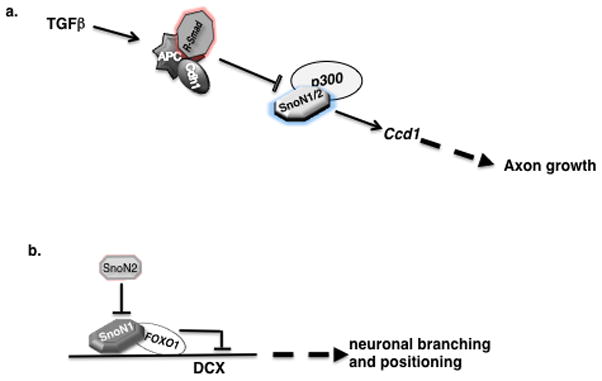

Figure 2. SnoN has versatile functions in the mammalian brain.

a. SnoN promotes axons growth in postmitotic neurons. SnoN associates with the transcriptional coactivator p300 to induce transcription of the Ccd1 gene, which has a critical role in axon growth. SnoN-induced axon growth is controlled by the ubiquitin ligase Cdh1-APC, which is recruited to SnoN by the TGFβ-Smad pathway. b. The SnoN isoforms, SnoN1 and SnoN2, have opposing roles in the coordinate regulation of neuronal branching and migration. SnoN1 promotes neuronal branching and inhibits neuronal migration. SnoN2 inhibits the ability of SnoN1 to control neuronal branching and migration. SnoN1 associates with the transcription FOXO1 to repress the expression of the DCX gene.

The regulation of SnoN function in axon development has been characterized, though undoubtedly these mechanisms are incompletely understood (Figure 2a). The ubiquitin ligase Cdh1-APC stimulates the ubiquitination and consequent degradation of SnoN in neurons and thereby limits axon growth ([10], Figure 2a). Accordingly, Cdh1-APC operates in the nucleus of developing neurons to restrict axon growth [10,85]. Cdh1 knockdown in rat pups leads to defasciculation of parallel fiber axons [86], suggesting that Cdh1-APC also controls the patterning of axons beyond simply restricting their growth. However, SnoN may not participate in the control of axon patterning downstream of Cdh1-APC [10].

The ability of neuronal Cdh1-APC to stimulate the degradation of SnoN is stimulated by activation of TGFβ-Smad2 signaling in neurons ([11], Figure 2a). Accordingly, TGFβ-Smad2 signaling restricts axon growth in granule neurons [11]. Conversely, inhibition of TGFβ signaling stimulates axon growth, including when myelin with its potent axon-inhibitory activities is used as the cellular substrate in cultures of primary granule neurons [11]. These findings raise the intriguing possibility that inhibition of TGFβ signaling may promote axon regeneration in neurons following injury.

The mechanisms by which SnoN promotes axon growth are also beginning to be elucidated (Figure 2a). Microarray analyses of SnoN-knockdown granule neurons have revealed that the majority of altered genes are downregulated, suggesting that SnoN may act as a transcriptional coactivator [12]. Consistent with this idea, SnoN associates with the transcriptional coactivator p300 ([12], Figure 2a). Knockdown of p300 inhibits axon growth, phenocopying the effect of SnoN knockdown [12]. The actin-binding protein Ccd1 has been uncovered as a critical SnoN-regulated target gene in neurons ([12], Figure 2a). Ccd1 localizes to axon terminals, and loss of function studies suggest that Ccd1 mediates SnoN-dependent axon growth in granule neuron [12]. SnoN and p300 are both required for Ccd1 transcription in neurons (Figure 2a). Collectively, studies of SnoN have defined an intricate cell-intrinsic transcriptional pathway that controls the growth of axons.

B. Isoform-specific roles of SnoN in neuron branching, migration and positioning

SnoN is not just one protein, but rather two proteins, SnoN1 and SnoN2, that are the products of two alternatively spliced-forms of Sno mRNA. The two SnoN proteins differ by a stretch of 46 amino acids found in SnoN1 but not SnoN2 [15]. SnoN1 and SnoN2 are both expressed in neurons [9,10], raising the question of whether the SnoN isoforms have redundant or non-redundant functions. Isoform specific knockdown of SnoN isoforms has revealed that SnoN1 and SnoN2 operate redundantly in axon growth ([9], Figure 2a). However isoform specific knockdown of the SnoN isoforms has also revealed non-redundant functions of SnoN1 and SnoN2 ([9], Figure 2b). Knockdown of SnoN2, but not SnoN1, leads to exuberant branching of axons in primary granule neurons [9]. Remarkably, knockdown of SnoN1 in the context of SnoN2 silencing suppresses the axon branching phenotype. These data suggest that SnoN1 stimulates excessive axon branching, and SnoN2 antagonizes SnoN1-dependent branching (Figure 2b).

Increasing evidence suggests that impaired neuronal migration is associated with excessive branching in primary neurons [87–90]. Consistent with this idea, knockdown of SnoN2 in vivo inhibits migration of granule cells from the external granule layer (EGL) to the internal granule layer (IGL) of the cerebellar cortex [9]. Knockdown of SnoN1 reverses the SnoN2 knockdown-induced cell migration phenotype. These data suggest that just as in the control of branching, SnoN1 and SnoN2 have opposing functions in the control of neuron migration from the EGL into the IGL in the cerebellar cortex (Figure 2b).

Once granule neurons reach the IGL from the EGL, they journey farther within the IGL to reach their final position with the older neurons settling in deeper regions inside the IGL and younger neurons residing in more superficial regions [79,91]. The establishment of neuronal positioning is critical for normal brain functions. Although the migration of granule neurons from the EGL to the IGL has been studied widely, the positioning of neurons within the IGL is just beginning to be investigated. SnoN control of neuronal positioning extends beyond their migration from EGL to the IGL [9]. Remarkably, knockdown of SnoN1 increases numbers of granule neurons residing within deeper areas of the IGL, suggesting that SnoN1 is required for proper granule neuron positioning [9].

How do the SnoN isoforms coordinately regulate neuronal branching and positioning in the cerebellar cortex? Since SnoN is a transcriptional coregulator, the SnoN isoforms would be expected to function together with a DNA-binding transcription factor to regulate neuronal branching and positioning. Recent studies suggest that SnoN1 forms a specific complex with the transcription factor FOXO1 and thereby regulates neuronal branching and positioning ([9], Figure 2b). In reporter assays, SnoN1 represses FOXO-dependent transcription. Consistent with opposing roles of the SnoN isoforms in neuronal branching and migration, SnoN2 antagonizes the ability of SnoN1 to repress FOXO-dependent transcription ([9], Figure 2b). The interaction of FOXO1 with SnoN1 is functionally relevant, as knockdown of FOXO1 in rat pups phenocopies the effect of SnoN1 knockdown on the positioning of granule neurons in the IGL [9]. These results suggest that SnoN1 and FOXO1 form a transcriptional corepressor complex that regulates neuronal positioning.

If SnoN1 and FOXO1 form a transcriptional repressor complex, what are the target genes that mediate the ability of this complex to control neuronal migration? Although these targets remain to be identified, one good candidate is the X-linked gene encoding the microtubule associated protein doublecortin (DCX) ([9], Figure 2b). Mutations of DCX represent an important cause of X-linked mental retardation and epilepsy[92–94]. Notably, inhibition of DCX impairs migration and stimulates neuronal branching [87,89,95,96]. Remarkably, FOXO1 and SnoN occupy regulatory sequences of the DCX gene and knockdown of FOXO1 or SnoN1 derepresses DCX expression [9]. These findings suggest that DCX represents a direct target of the FOXO1-SnoN1 transcriptional repressor complex. Accordingly, knockdown of DCX suppresses SnoN1 knockdown-induced phenotypes of neuronal migration and branching. A model can be envisaged to explain the isoform specific role of sno gene products in neuron branching, migration and positioning, whereby SnoN1 is recruited by FOXO1 to promoter elements of the target gene DCX to repress its transcription, and this cell intrinsic pathway is under negative regulation by SnoN2 (Figure 2b).

Collectively, recent studies have revealed that SnoN is a critical player in distinct biological processes within the mammalian brain including axon growth, branching, and neuronal positioning (Figure 2). SnoN regulation of these distinct processes in postmitotic neurons is intimately linked to its ability to form multiprotein transcriptional complexes that positively or negatively regulate transcription. The newly identified functions of SnoN in neurons have important implications for brain development and function.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

The transcriptional co-regulator SnoN is a critical and versatile regulator of TGFβ-induced transcription and responses. SnoN controls TGFβ-mediated responses by acting as a transcriptional corepressor or transcriptional coactivator. The mechanisms of transcriptional activation are beginning to be elucidated. However, further research is required to elucidate these mechanisms. For example, unbiased approaches should be used to identify novel SnoN-interacting proteins that modulate SnoN-dependent transcription. The physiological significance of SnoN regulation of TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest and EMT should be addressed by employing SnoN loss and gain function approaches in different model systems including 3D cultures and in vivo. As EMT is a fundamental process during different stages of embryonic development including gastrulation, neural crest migration and heart valve formation, it will be important to characterize the role of SnoN in these processes using conditional sno knockout or knockin animal models [45].

SnoN has established roles in cancer biology. The emerging picture is that SnoN exerts a dual role in cancer, i.e. as a tumor promoter or suppressor depending on various factors including the stage of cancer and the level of SnoN expression. An important goal of future studies should be to understand the mechanisms that mediate the two opposing roles of SnoN in cancer including identification of upstream regulators and downstream effectors in the regulation of tumorigenesis using in vivo xenograft and transgenic in vivo models of cancer. Increasingly, it is becoming clear that the tumor microenvironment, vascular and immune systems play important roles in cancer initiation and progression [63]. Whether regulation of SnoN-mediated effects in non-tumor derived cells can modulate the ability of TGFβ to control tumorigenesis remains to be addressed.

SnoN is also emerging as a critical cell-intrinsic regulator of distinct biological processes in the developing mammalian brain, though in many ways the recent reports on this subject represent the tip of the iceberg on the roles and mechanisms of SnoN in neurobiology. Nevertheless, we can draw several important conclusions from these studies. SnoN appears to play an essential role in the control of axon growth. In this function, the two closely related isoforms of SnoN, SnoN1 and SnoN2, operate in a redundant manner to activate transcription including the gene encoding the signaling molecule Ccd1. How SnoN acts as a transcriptional coactivator in neurons remains to be elucidated, though interaction with p300 appears to play a role. The transcription factor and other associated factors, besides p300, that cooperate with both SnoN1 and SnoN2 to induce transcription remain to be identified. In addition, the role of additional target genes beyond Ccd1 in the control of axon growth is an area that requires attention. Whether additional enzymes, besides the ubiquitin ligase Cdh1-APC, regulate SnoN function in axon growth has not been explored. Finally, the role of SnoN in axon growth in other regions of the brain beyond the cerebellar cortex is an important question. Initial studies suggest that SnoN is also required for axon growth in hippocampal neurons [10]. However, a thorough study of this question requires a mouse genetics approach. The generation of transgenic mice expressing SnoN or knockout mice in which the sno gene is disrupted will facilitate studies of SnoN in axon growth in circumstances other than development including in the potential for SnoN to promote axon regeneration following injury and disease.

The isoform specific functions of SnoN1 and SnoN2 in the control of neuronal branching and migration is an excellent example of how the functions of alternatively spliced protein products that oppose each other may be hidden from view if one focuses on complete knockouts or knockdowns of a protein. In future studies, it will be interesting to determine how the SnoN1-FOXO1 repressor complex operates in neurons. How is this complex regulated in neurons, and what are the downstream target genes that are repressed in the control of neuronal positioning?

While studies of SnoN in cancer biology and neurobiology have been proceeding in parallel, there are likely many interesting links between the two. For example, the regulation of SnoN by Cdh1-APC operates both in the control of the G1 phase of the cell cycle in proliferating as well as in the postmitotic neurons in the control of axon growth [10,17,37]. Likewise, the control of SnoN by the TGFβ-Smad2 signaling pathway represents a cassette that functions both in cycling cells and postmitotic neurons, albeit with different biological responses [7,10,17,34,37]. Extrapolating from these links, it is tempting to speculate that sumoylation of SnoN or its interaction with the chromatin remodeling protein ING2 in the control of EMT and cell proliferation in cycling cells may have important yet to be identified roles in postmitotic neurons. Conversely, the newly defined isoform specific functions of SnoN1 and SnoN2 and the identification of the SnoN1-FOXO1 transcriptional repressor complex in neurons may have important functions in proliferating cells and tumorigenesis. Progress in SnoN biology in the years ahead should lead to advances in both cancer biology and neurobiology. Ultimately, improved understanding of SnoN holds the prospect for the development of novel drugs that target diverse diseases including cancer and neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Alberta Cancer Foundation to S.B and the National Institutes of Health to A.B. (NS041021).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nomura N, Sasamoto S, Ishii S, Date T, Matsui M, Ishizaki R. Isolation of human cDNA clones of ski and the ski-related gene, sno. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5489–500. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.14.5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer PL, Colmenares C, Stavnezer E, Hughes SH. Sequence and biological activity of chicken snoN cDNA clones. Oncogene. 1993;8:457–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson-White S, Crittenden R. Proto-oncogene Sno expression, alternative isoforms and immediate early serum response. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2930–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelzer T, Lyons GE, Kim S, Moreadith RW. Cloning and characterization of the murine homolog of the sno proto-oncogene reveals a novel splice variant. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:114–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199602)205:2<114::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sleeman JP, Laskey RA. Xenopus c-ski contains a novel coiled-coil protein domain, and is maternally expressed during development. Oncogene. 1993;8:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takaesu NT, Hyman-Walsh C, Ye Y, Wisotzkey RG, Stinchfield MJ, O'Connor MB, Wotton D, Newfeld SJ. dSno facilitates baboon signaling in the Drosophila brain by switching the affinity of Medea away from Mad and toward dSmad2. Genetics. 2006;174:1299–313. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroschein SL, Wang W, Zhou S, Zhou Q, Luo K. Negative feedback regulation of TGF-beta signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science. 1999;286:771–4. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Liu X, Ng-Eaton E, Lodish HF, Weinberg RA. SnoN and Ski protooncoproteins are rapidly degraded in response to transforming growth factor beta signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12442–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh MA, et al. An isoform-specific SnoN1-FOXO1 repressor complex controls neuronal morphogenesis and positioning in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 2011;69:930–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stegmüller J, Konishi Y, Huynh MA, Yuan Z, Dibacco S, Bonni A. Cell-intrinsic regulation of axonal morphogenesis by the Cdh1-APC target SnoN. Neuron. 2006;50:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stegmüller J, Huynh MA, Yuan Z, Konishi Y, Bonni A. TGFbeta-Smad2 signaling regulates the Cdh1-APC/SnoN pathway of axonal morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1961–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3061-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeuchi Y, Stegmüller J, Netherton S, Huynh MA, Masu M, Frank D, Bonni S, Bonni A. A SnoN-Ccd1 pathway promotes axonal morphogenesis in the mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4312–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0126-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Sun Y, Weinberg RA, Lodish HF. Ski/Sno and TGF-beta signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo K, Stroschein SL, Wang W, Chen D, Martens E, Zhou S, Zhou Q. The Ski oncoprotein interacts with the Smad proteins to repress TGFbeta signaling. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2196–206. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pot I, Bonni S. SnoN in TGF-beta signaling and cancer biology. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:319–28. doi: 10.2174/156652408784533797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomura T, Khan MM, Kaul SC, Dong HD, Wadhwa R, Colmenares C, Kohno I, Ishii S. Ski is a component of the histone deacetylase complex required for transcriptional repression by Mad and thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:412–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stroschein SL, Bonni S, Wrana JL, Luo K. Smad3 recruits the anaphase-promoting complex for ubiquitination and degradation of SnoN. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2822–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.912901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JW, Krawitz AR, Chai J, Li W, Zhang F, Luo K, Shi Y. Structural mechanism of Smad4 recognition by the nuclear oncoprotein Ski: insights on Ski-mediated repression of TGF-beta signaling. Cell. 2002;111:357–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson TJ, Ramu C, Gemund C, Aasland R. The APECED polyglandular autoimmune syndrome protein, AIRE-1, contains the SAND domain and is probably a transcription factor. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:242–4. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyman T, et al. The crystal structure of the Dachshund domain of human SnoN reveals flexibility in the putative protein interaction surface. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters JM. The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome: a machine designed to destroy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:644–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen SB, Zheng G, Heyman HC, Stavnezer E. Heterodimers of the SnoN and Ski oncoproteins form preferentially over homodimers and are more potent transforming agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1006–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyman HC, Stavnezer E. A carboxyl-terminal region of the ski oncoprotein mediates homodimerization as well as heterodimerization with the related protein SnoN. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26996–7003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagase T, Nomura N, Ishii S. Complex formation between proteins encoded by the ski gene family. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13710–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng G, Blumenthal KM, Ji Y, Shardy DL, Cohen SB, Stavnezer E. High affinity dimerization by Ski involves parallel pairing of a novel bipartite alpha-helical domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31855–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarapore P, et al. DNA binding and transcriptional activation by the Ski oncoprotein mediated by interaction with NFI. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3895–903. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.19.3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massagué J. The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts AB, Flanders KC, Heine UI, Jakowlew S, Kondaiah P, Kim SJ, Sporn MB. Transforming growth factor-beta: multifunctional regulator of differentiation and development. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1990;327:145–54. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wrana JL, Attisano L, Wieser R, Ventura F, Massagué J. Mechanism of activation of the TGF-beta receptor. Nature. 1994;370:341–7. doi: 10.1038/370341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attisano L, Wrana JL. Smads as transcriptional co-modulators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:235–43. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. Smad Transcritional Co-activators and Co-repressors. In: ten Dijke P, Heldin CH, editors. Smad Signal Transduction. Springer; 2006. pp. 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wotton D, Massagué J. Smad transcriptional corepressors in TGF beta family signaling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;254:145–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonni S, Wang HR, Causing CG, Kavsak P, Stroschein SL, Luo K, Wrana JL. TGF-beta induces assembly of a Smad2-Smurf2 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets SnoN for degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:587–95. doi: 10.1038/35078562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy L, Howell M, Das D, Harkin S, Episkopou V, Hill CS. Arkadia activates Smad3/Smad4-dependent transcription by triggering signal-induced SnoN degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6068–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00664-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagano Y, et al. Arkadia induces degradation of SnoN and c-Ski to enhance transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20492–501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan Y, Liu X, Kirschner MW. The anaphase-promoting complex mediates TGF-beta signaling by targeting SnoN for destruction. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1027–39. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarker KP, et al. ING2 as a novel mediator of transforming growth factor-beta-dependent responses in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13269–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708834200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarker KP, Wilson SM, Bonni S. SnoN is a cell type-specific mediator of transforming growth factor-beta responses. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13037–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He J, Tegen SB, Krawitz AR, Martin GS, Luo K. The transforming activity of Ski and SnoN is dependent on their ability to repress the activity of Smad proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30540–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinagawa T, Dong HD, Xu M, Maekawa T, Ishii S. The sno gene, which encodes a component of the histone deacetylase complex, acts as a tumor suppressor in mice. Embo J. 2000;19:2280–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Netherton SJ, Bonni S. Suppression of TGFbeta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition like phenotype by a PIAS1 regulated sumoylation pathway in NMuMG epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu Q, et al. Dual role of SnoN in mammalian tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:324–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01394-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang Y, Massague J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyazono K. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and progression of cancer. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85:314–23. doi: 10.2183/pjab.85.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zavadil J, Böttinger EP. TGF-beta and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng SB, et al. Kinetic characterization of novel pyrazole TGF-beta receptor I kinase inhibitors and their blockade of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2293–304. doi: 10.1021/bi048851x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valcourt U, Kowanetz M, Niimi H, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. TGF-beta and the Smad signaling pathway support transcriptomic reprogramming during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1987–2002. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krakowski AR, Laboureau J, Mauviel A, Bissell MJ, Luo K. Cytoplasmic SnoN in normal tissues and nonmalignant cells antagonizes TGF-{beta} signaling by sequestration of the Smad proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504107102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang F, Lundin M, Ristimaki A, Heikkila P, Lundin J, Isola J, Joensuu H, Laiho M. Ski-related novel protein N (SnoN), a negative controller of transforming growth factor-beta signaling, is a prognostic marker in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5005–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Champagne KS, Kutateladze TG. Structural insight into histone recognition by the ING PHD fingers. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10:432–41. doi: 10.2174/138945009788185040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pena PV, Davrazou F, Shi X, Walter KL, Verkhusha VV, Gozani O, Zhao R, Kutateladze TG. Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature. 2006;442:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature04814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi X, et al. ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature. 2006;442:96–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsu YH, Sarker KP, Pot I, Chan A, Netherton SJ, Bonni S. Sumoylated SnoN represses transcription in a promoter-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33008–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wrighton KH, Liang M, Bryan B, Luo K, Liu M, Feng XH, Lin X. Transforming growth factor-beta-independent regulation of myogenesis by SnoN sumoylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6517–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nanjundan M, et al. Overexpression of SnoN/SkiL, amplified at the 3q26.2 locus, in ovarian cancers: a role in ovarian pathogenesis. Mol Oncol. 2008;2:164–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan D, Zhu Q, Luo K. SnoN functions as a tumour suppressor by inducing premature senescence. EMBO J. 2009;28:3500–13. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Band AM, Laiho M. SnoN oncoprotein enhances estrogen receptor-alpha transcriptional activity. Cell Signal. 2012;24:922–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jakowlew SB. Transforming growth factor-beta in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:435–57. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Massagué J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Massagué J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boone B, Haspeslagh M, Brochez L. Clinical significance of the expression of c-Ski and SnoN, possible mediators in TGF-beta resistance, in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edmiston JS, Yeudall WA, Chung TD, Lebman DA. Inability of transforming growth factor-beta to cause SnoN degradation leads to resistance to transforming growth factor-beta-induced growth arrest in esophageal cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4782–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imoto I, et al. SNO is a probable target for gene amplification at 3q26 in squamous-cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:559–65. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Poser I, Rothhammer T, Dooley S, Weiskirchen R, Bosserhoff AK. Characterization of Sno expression in malignant melanoma. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akagi I, et al. SnoN overexpression is predictive of poor survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2965–75. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang X, Egawa K, Xie Y, Ihn H. The expression of SnoN in normal human skin and cutaneous keratinous neoplasms. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:579–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bravou V, Antonacopoulou A, Papadaki H, Floratou K, Stavropoulos M, Episkopou V, Petropoulou C, Kalofonos H. TGF-beta repressors SnoN and Ski are implicated in human colorectal carcinogenesis. Cell Oncol. 2009;31:41–51. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coles AH, Liang H, Zhu Z, Marfella CG, Kang J, Imbalzano AN, Jones SN. Deletion of p37Ing1 in mice reveals a p53-independent role for Ing1 in the suppression of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2054–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kataoka H, et al. ING1 represses transcription by direct DNA binding and through effects on p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5785–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pedeux R, et al. ING2 regulates the onset of replicative senescence by induction of p300-dependent p53 acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6639–48. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6639-6648.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.de la Torre-Ubieta L, Bonni A. Transcriptional regulation of neuronal polarity and morphogenesis in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 2011;72:22–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim AH, Bonni A. Thinking within the D box: initial identification of Cdh1-APC substrates in the nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Altman J, Bayer SA. Development of the Cerebellar System: In Relation to Its Evolution, Structure, and Functions. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hatten ME. Central nervous system neuronal migration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:511–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Palay SL, Chan-Palay V. Cerebellar Cortex: Cytology and Organization. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ramón y Cajal S. Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chédotal A. Should I stay or should I go? Becoming a granule cell. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:163–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang Y, Kim AH, Bonni A. The dynamic ubiquitin ligase duo: Cdh1-APC and Cdc20-APC regulate neuronal morphogenesis and connectivity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huynh MA, Stegmüller J, Litterman N, Bonni A. Regulation of Cdh1-APC function in axon growth by Cdh1 phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4322–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5329-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Konishi Y, Stegmüller J, Matsuda T, Bonni S, Bonni A. Cdh1-APC controls axonal growth and patterning in the mammalian brain. Science. 2004;303:1026–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1093712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bielas SL, Serneo FF, Chechlacz M, Deerinck TJ, Perkins GA, Allen PB, Ellisman MH, Gleeson JG. Spinophilin facilitates dephosphorylation of doublecortin by PP1 to mediate microtubule bundling at the axonal wrist. Cell. 2007;129:579–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guerrier S, et al. The F-BAR domain of srGAP2 induces membrane protrusions required for neuronal migration and morphogenesis. Cell. 2009;138:990–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kappeler C, et al. Branching and nucleokinesis defects in migrating interneurons derived from doublecortin knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1387–400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagano T, Morikubo S, Sato M. Filamin A and FILIP (Filamin A-Interacting Protein) regulate cell polarity and motility in neocortical subventricular and intermediate zones during radial migration. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9648–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2363-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Komuro H, Rakic P. Distinct modes of neuronal migration in different domains of developing cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1478–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01478.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.des Portes V, et al. doublecortin is the major gene causing X-linked subcortical laminar heterotopia (SCLH) Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1063–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–71. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gleeson JG, et al. Characterization of mutations in the gene doublecortin in patients with double cortex syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:146–53. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<146::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bai J, Ramos RL, Ackman JB, Thomas AM, Lee RV, LoTurco JJ. RNAi reveals doublecortin is required for radial migration in rat neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1277–83. doi: 10.1038/nn1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koizumi H, Higginbotham H, Poon T, Tanaka T, Brinkman BC, Gleeson JG. Doublecortin maintains bipolar shape and nuclear translocation during migration in the adult forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:779–86. doi: 10.1038/nn1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]