Abstract

Nascent evidence indicates that mitochondrial fission, fusion, and transport are subject to intricate regulatory mechanisms that intersect with both well-characterized and emerging signaling pathways. While it is well established that mutations in components of the mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery can cause neurological disorders, relatively little is known about upstream regulators of mitochondrial dynamics and their role in neurodegeneration. Here, we review posttranslational regulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion enzymes, with particular emphasis on dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), as well as outer mitochondrial signaling complexes involving protein kinases and phosphatases. We also review recent evidence that mitochondrial dynamics has profound consequences for neuronal development and synaptic transmission and discuss implications for clinical translation.

Keywords: mitochondrial fission, mitochondrial fusion, mitochondrial transport, protein phosphorylation, dynamin-related protein 1, mitofusin, optic atrophy 1, neurodegeneration, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, autosomal dominant optic atrophy, synaptic transmission, synaptogenesis

Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction occurs in a wide range of neurological disorders including Alzheimer disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington disease (HD), Parkinson Disease (PD), and a subset of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA). For the most part, however, it remains unknown as to whether neurodegeneration in these disorders is triggered by mitochondrial dysfunction, or whether mitochondrial dysfunction results from the disease state.

While excellent recent reviews have highlighted links between mitochondrial dysfunction and disease (Cho et al., 2010; Martin, 2010; Morais and De Strooper, 2010; Moreira et al., 2010; Pandey et al., 2010; Patten et al., 2010; Pickrell and Moraes, 2010; Rodolfo et al., 2010; Schon and Przedborski, 2011; Witte et al., 2010), this review focuses on cellular signaling pathways that impact mitochondrial morphology and transport and potential dysregulation of these signaling pathways in neuronal injury and disease.

Mitochondrial shape and function, and ultimately cellular homeostasis, is determined by balanced mitochondrial fission and fusion events. Research over the last decade has lead to an appreciation of the complexity of the cellular signaling mechanisms that sculpt the mitochondrial network in response to changing needs of the cell and the organism. Below, we discuss how dynamic protein-protein interactions and posttranslational modifications control the rate of fission and fusion of mitochondria and review our current understanding of the role of mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal development and function.

1. Regulation of mitochondrial fission

1.1 Drp1 structure/function

Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1, encoded by the human DNM1L gene) is a large GTPase that cycles between cytosol and the outer mitochondria membrane (OMM), where it oligomerizes into spiral-shaped structures to physically pinch a single mitochondrion into two (Hoppins et al., 2007). Drp1 contains four domains: 1) an N-terminal GTPase domain which harbors the enzymatic activity, 2) a middle domain necessary for oligomerization, 3) an alternative-spliced variable domain that contains most posttranslational modification sites, and 4) a C-terminal GTPase effector domain (GED) which interacts with the GTPase domain (Figure 1A). According to recently published crystal structures of dynamin-1 (Faelber et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2011), the α-helices of the MID and GED form a “stalk” domain, two of which interact in a criss-cross fashion to assemble a Drp1 dimer (Figure 1B, C). Similar to dynamin at clathrin-coated vesicles (Hoppins et al., 2007; Praefcke and McMahon, 2004), the catalytic cycle of Drp1 is thought to occur in four discrete steps. First, Drp1 is recruited from the cytosol to the OMM. Second, Drp1 oligomerizes to form spirals around the OMM. Third, GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP to power constriction of the Drp1 oligomer. Fourth, the Drp1 oligomer disassembles and Drp1 is released back into the cytosol.

Figure 1.

Posttranslational regulation of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1). A) Based on sequence similarity to dynamin, the Drp1 coding sequence can be subdivided into four domains (GTP, GTPase domain; MID, middle domain; VD, variable domain; GTPase effector domain, GED). Shown are insertion points for alternatively spliced coding sequences and sites of posttranslational modification (P, phosphorylation; NO, S-nitrosylation; SUMO, sumoylation). The sequence alignment highlights the phylogenetic conservation of the S-nitrosylation and phosphorylation sites. B) Fold model of a Drp1 monomer based on crystal structures of dynamin-1 (Faelber et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2011). MID and GED form an extended stalk that separates the GTPase from the variable domain and mediates dimerization and higher order assembly of Drp1. C) Model of Drp1 fission complex assembly (segment of helix with three Drp1 dimers shown in cross-section). Adjacent rungs of the Drp1 helix interact via GTPase domains.

Drp1 is subject to alternative splicing, with one alternative exon separating subdomains A and B of the GTPase domain, and tandem alternative exons encoding portions of the variable domain (Chen et al., 2000). Most of the 8 potential splice variants generated by independent inclusion of the three alternative exons exist as expressed sequence tags, and the longest Drp1 isoform containing all three alternative exons is abundantly and selectively expressed in the brain (Chen et al., 2000; Uo et al., 2009). Because alternative exons allow for splice-specific phosphorylation (Dephoure et al., 2008) and sumoylation (Figueroa-Romero et al., 2009), it is important to be cognizant that different Drp1 splice forms may be differentially regulated by posttranslational modifications.

1.2 Drp1 interactions at the OMM

The number of proteins that physically or functionally interact with Drp1 continues to grow. Originally identified as critical for mitochondrial fission in yeast (Mozdy et al., 2000), Fis1 was suggested to recruit Drp1 to the OMM in mammalian cells (Koch et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2003). However, other studies failed to find support for role for Fis1 as a core component of the mitochondrial fission machinery (Gandre-Babbe and van der Bliek, 2008; James et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004; Otera et al., 2010), suggesting instead that Fis1 may have acquired a modulatory role during metazoan evolution. An RNA interference screen in Drosophila cells led to the identification of mitochondrial fission factor (Mff), an OMM-anchored protein required for mitochondrial fragmentation (Gandre-Babbe and van der Bliek, 2008). Mff directly binds to Drp1 and is necessary and sufficient for functional association of Drp1 with mitochondria (Gandre-Babbe and van der Bliek, 2008; Otera et al., 2010).

Adding further complexity, OMM-localized proteins that inhibit Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission have also been identified. MiD49 (concurrently identified as mitochondrial elongation factor 1 [MIEF1]) and MiD51 form fission-inhibitory complexes with Drp1 at the OMM, resulting in elongation of the mitochondrial network (Palmer et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011). While further work is needed to establish the mechanism by which MiD49/51/MIEF1 inhibit mitochondrial fission, it is plausible that these proteins create a latent pool of Drp1 at the OMM. As yet uncharacterized postranslational modifications events may dissociate these inhibitory complexes to allow Drp1 to productively engage with Mff, resulting in Drp1 oligomerization and mitochondrial fission. Since MiD49 was shown to robustly interact with Fis1 (Zhao et al., 2011), it is conceivable that the fission-promoting activity of Fis1 involves liberation of Drp1 from inhibitory complexes with MiD49/51/MIEF1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model of Drp1 recruitment to the OMM by docking proteins. Drp1 can be recruited from the cytosol via the MiD49/MiD51/MIEF1 complex, which sequesters Drp1 in a fission-incompetent state (1). Fis1 binding to MiD49/MiD51/MIEF1 liberates Drp1 (2) to facilitate Drp1 association with Mff (3) and formation of Mff::Drp1 fission complexes (4). Residency of Drp1 in various complexes is determined by relative levels of the docking proteins as well as posttranslational modifications controlling binding affinities.

1.3 Drp1 phosphorylation

Drp1 is regulated by multiple posttranslational modifications (Santel and Frank, 2008). One of the most studied modifications to Drp1 is the reversible addition of phosphate groups to conserved serine residues. Two sites located at the VD/GED junction, serine 635 and 656 (numbering according to the longest, brain enriched Drp1 splice variant from rat), were reported to have opposing effects on Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation (Figure 1). To avoid confusion due to the use of multiple Drp1 splice variants from different species in the literature, we propose a phosphorylation site nomenclature, which includes the kinase that was first shown to target the site. Specifically, we designate Ser656 as SerPKA and Ser635 as SerCDK. The Blackstone group and our laboratory simultaneously identified protein kinase A (PKA) as a potent Drp1 regulator (Chang and Blackstone, 2007; Cribbs and Strack, 2007). Phosphorylation of the highly conserved SerPKA inhibits Drp1, resulting in mitochondrial elongation by unopposed fusion. PKA phosphorylation of Drp1 has a neuroprotective effect, since replacement of endogenous with constitutively phosphorylated Drp1 (SerPKA→Asp) inhibits cytochrome c release and apoptotic cell death in neuronal PC12 cells, while expression of Drp1 that cannot be phosphorylated (SerPKA→Ala) sensitizes cells to several apoptosis inducers (Cribbs and Strack, 2007). Furthermore, both mitochondrial elongation and neuroprotection conferred by OMM-localized AKAP1 (see 3.1) depends on the SerPKA site in Drp1 (Merrill et al., 2011). As to the effect of phosphorylation on the catalytic cyle of Drp1, it has been reported that SerPKA→Asp substitution and phosphorylation by PKA inhibits the GTPase activity of Drp1 (Chang and Blackstone, 2007), although this was not observed in another study (Cribbs and Strack, 2007) and may therefore depend on in vitro assay conditions. According to crosslinking, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) and single particle tracking analyses, phosphorylation of Drp1 at SerPKA by OMM-localized PKA promotes OMM accumulation of large Drp1 complexes that exchange more slowly with cytosolic Drp1 pools than unphosphorylated Drp1 (Merrill et al., 2011). In combination, these data suggest a model in which SerPKA phosphorylation modulates the rate and/or geometry of Drp1 oligomerization at the OMM to disfavor the formation of short, fission competent Drp1 spirals.

The predominant phosphatase that dephosphorylates Drp1 at SerPKA to promote mitochondria fragmentation is the calcium-dependent protein phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) (Cereghetti et al., 2008; Cribbs and Strack, 2007). Specifically expressed in neurons, the neuron-specific and OMM-targeted protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) heterotrimer containing the Bβ2 regulatory subunit (see 3.2) may also dephosphorylate Drp1 at SerPKA (Dickey and Strack, 2011).

Drp1 is also phosphorylated at SerCDK by the cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1)/cyclin B complex during mitosis. Intriguingly, even though SerCDK is only 11 amino acids upstream of SerPKA, SerCDK phosphorylation was reported to have the opposite effect on the cellular activity of Drp1, enhancing mitochondrial fragmentation (Taguchi et al., 2007). The SerCDK→Ala substitution attenuated both mitotic fragmentation of mitochondria, as well as in vitro phosphorylation of Drp1 by the Cdk1/cyclin B complex. Drp1 activation by SerCDK phosphorylation could contribute to proper segregation of mitochondria between the two daughter cells (Taguchi et al., 2007). SerCDK is heavily phosphorylated in asynchronously growing cell cultures and in postmitotic cells, suggesting the involvement of additional kinases. Indeed, cdk5 promotes Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission in neuronal cells (Meuer et al., 2007), and Drp1 SerCDK was recently reported to be a critical substrate for protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) in oxidative stress-induced neuronal death (Qi et al., 2011). However, another report (Cereghetti et al., 2008) and our own unpublished experiments failed to provide support for a major effect of Drp1 SerCDK phosphorylation or mutation on mitochondrial morphology in interphase or postmitotic cells. Therefore, the functional consequences of Drp1 phosphorylation at SerCDK may be cell cycle-, cell type-, or Drp1 splice form-specific.

1.4 S-Nitrosylation of Drp1

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important second messenger and neurotransmitter generated through the oxidation of L-arginine by nitric oxide synthases (Knowles and Moncada, 1994; Luo and Zhu, 2011). NO signals through both cGMP pathways (via activation of soluble guanylate cyclase) and through direct nitrosylation and nitration of target proteins (Foster et al., 2009; Mujoo et al., 2011). Dysregulation of NO signaling has been implicated in many neurodegenerative disorders including AD, ALS, HD, PD, as well as ischemic stroke (Knott and Bossy-Wetzel, 2009). A role for NO in mitochondrial dynamics was first reported by Barsoum and co-workers, who demonstrated that treatment with the NO-donor S-nitrosocysteine (SNOC) or stimulation of endogenous NO production via activation of NMDA receptors resulted in Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation in primary neuronal cultures (Barsoum et al., 2006). A subsequent study aimed at determining the molecular basis of NO-induced fission found that NO activates Drp1 by S-nitrosylation of a conserved cysteine residue in the GED, eight amino acids downstream of SerPKA (Cho et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Cho and colleagues presented evidence to suggest that S-nitrosylation increases Drp1 GTPase activity and leads to covalent dimerization of Drp1 (Cho et al., 2009). However, these findings have come under scrutiny, as a subsequent study found no effect of S-nitrosylation on Drp1 GTPase activity or oligomerization (Bossy et al., 2010). Additional dispute exists over whether increased Drp1 S-nitrosylation is specific to AD (Cho et al., 2009) or is a general feature of neurodegeneration (Bossy et al., 2010).

Nitrosylation is known to influence several signaling pathways, including cell cycle regulation by the Cdk1/cyclin B complex (Lee et al., 2009). As discussed in section 1.3, phosphorylation of Drp1 at SerCDK by Cdk1/cyclin B increases mitochondrial fragmentation (Taguchi et al., 2007). Interestingly, it was shown that NO donor treatment of HEK293 cells enhances Drp1 phosphorylation at SerCDK and translocation to mitochondria (Bossy et al., 2010). This suggests that NO can modulate the activity of kinases/phosphatases that target SerCDK, or that Drp1 S-nitrosylation modulates the accessibility of SerCDK for kinases/phosphatases. Further work is needed to unravel the complex interplay between Drp1’s closely spaced phosphorylation and S-nitrosylation sites.

1.5 Drp1 ubiquitination

Ubiquitin (Ub) is a small protein that can be reversibly added to lysine residues on target proteins through the action of ubiquitin ligase complexes. The addition of Ub has a range of effects on protein function and stability depending on whether monomers (mono- and multi-ubiquitination) or chains are added (polyubiquitination) to targets, and depending on which Ub Lys residue is used for chain building. Generally, monomer addition regulates protein activity or trafficking, while polyubiquitylation directs a protein to the proteosome for subsequent degradation (Ikeda and Dikic, 2008; Li and Ye, 2008; Winget and Mayor, 2010).

Drp1 has been reported to be regulated by two mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligases, MARCH5 and Parkin. Initial studies suggested that MARCH5 degrades both Drp1 and Fis1, leading to unopposed mitochondrial fusion (Nakamura et al., 2006; Yonashiro et al., 2006). However, subsequent studies came to essentially opposite conclusions, providing evidence that MARCH5 inhibition by RNAi or dominant-negative approaches disrupts Drp1’s mitochondrial division cycle (Karbowski et al., 2007) and leads to stabilization of the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn1 (Park et al., 2010).

Parkin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase mutated in early onset autosomal recessive forms of PD (Biskup et al., 2008; Kitada et al., 1998). Genetic epistasis experiments in Drosophila indicate that Parkin operates in the same pathway and downstream of another protein mutated in familial PD, the mitochondria-targeted PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) (Clark et al., 2006; Park et al., 2006). In mammalian cells, Parkin loss has been shown to promote Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation (Lutz et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011). According to one recent report, Parkin can directly ubiquitinate Drp1, leading to Drp1 degradation and mitochondrial elongation (Wang et al., 2011). Other studies, however, came to the conclusion that Drp1 is not a direct target of the PINK1/Parkin pathway (Gegg et al., 2010; Glauser et al., 2011; Rakovic et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 2010). Further studies are needed to reconcile these conflicting results, to identify the relevant Ub ligase(s), and to establish the physiological relevance of Drp1 ubiquitination.

1.6 Drp1 sumoylation

The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protein has also been implicated in the regulation of Drp1 (Figueroa-Romero et al., 2009; Harder et al., 2004; Wasiak et al., 2007; Zunino et al., 2009). Sumoylation has been suggested to protect Drp1 from Ub modification and/or enhance Drp1 association with membranes (Harder et al., 2004). Sumoylation was also reported to contribute to the stable association of Drp1 with mitochondrial Bax/Bak foci during staurosporine-induced apoptosis (Wasiak et al., 2007). Drp1 sumoylation is counteracted by the SUMO protease, SenP5 (Zunino et al., 2007). SenP5 is activated at the G2/M transition of the cell cycle (Di Bacco et al., 2006; Zunino et al., 2009), and accelerates cycling of Drp1 between mitochondria and cytosol to promote mitochondrial fragmentation during mitosis (Zunino et al., 2009). Work by Figueroa-Romero et al. showed that Drp1 is sumoylated at eight non-consensus sites in the VD, four of which localize to an alternatively spliced insert (Figueroa-Romero et al., 2009) (Figure 1). A sumoylation-defective Drp1 mutant (Lys→Arg) was still efficiently ubiquitinated and translocated to mitochondria in response to staurosporine treatment, raising questions as to the functional significance of Drp1 sumoylation (Figueroa-Romero et al., 2009).

2. Regulation of mitochondrial fusion

Three large dynamin-family GTPases cooperate in the fusion of mitochondrial membranes in mammals. Mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn1/2) are transmembrane proteins that mediate fusion of the OMM (Chen et al., 2003; Eura et al., 2003; Legros et al., 2002; Santel and Fuller, 2001), while the intermembrane space (IMS)-localized optic atrophy 1 (Opa1) mediates fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) (Cipolat et al., 2004; Jones and Fangman, 1992; Olichon et al., 2002). Posttranslational modifications and regulatory interactions of mitochondrial fusion enzymes are not as well understood as those of Drp1. Since mutations of mitochondrial fusion proteins are associated with neurological disorders (Alexander et al., 2000; Delettre et al., 2000), an understanding of regulatory pathways in mitochondrial fusion may lead to novel therapeutic targets.

2.1 Regulation of mitofusins by Bcl-2-family proteins

Mfn1 and Mfn2 are essential GTPases that mediate fusion of the OMM (Benard and Karbowski, 2009; Westermann, 2010). Mechanistically, this is thought to involve tethering of adjacent mitochondria via coiled-coil domain mediated transmitochondrial homo- or heterodimerization of the mitofusins (Koshiba et al., 2004). While there is some functional redundancy between the mitofusins (Chen et al., 2003), there is also evidence for functional specialization and synergy (Hoppins et al., 2011). Specifically, Mfn1 is required for the initial tethering of mitochondria (Ishihara et al., 2004) and is necessary for subsequent fusion of the inner membrane by Opa1 (Cipolat et al., 2004). Mfn2 is the predominant mitofusin in the brain (Eura et al., 2003), and has been reported to function as a signaling GTPase (Neuspiel et al., 2005). Additional research supports a role of Mfn2 in regulating axonal transport of mitochondrial through an interaction with the Miro/Milton complex (Misko et al., 2010) (see section 4.1). Missense mutations in Mfn2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disorder type 2A2 (CMT2A2) (Palau et al., 2009; Reilly et al., 2011; Zuchner et al., 2004), a common autosomal dominant peripheral neuropathy associated with axon degeneration. Over 50 mutations have been identified that are located throughout the Mfn2 coding sequence (Chung et al., 2006), indicating that Mfn2 is critical for the survival of neurons with long axonal projections.

Induction of apoptosis is thought to depend on mitochondrial fragmentation (Martinou and Youle, 2006), whether through an increase in fission rates, a decrease in fusion rates, or a combination of the two. The Bcl-2 family of proteins includes both positive and negative apoptosis regulators, and several Bcl-2 family members have non-canonical roles by associating with mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. The C. elegans Bcl-2 ortholog, ced-9, has been shown to interact with Fzo1, the single mitofusin in C. elegans, to increase mitochondrial elongation (Delivani et al., 2006; Rolland et al., 2009). There is recent evidence that mammalian Bcl-xL may stimulate mitochondrial fusion as well (Hoppins et al., 2011).

Initial work showed that Bax/Bak double knockout cells have highly fragmented mitochondria and suggested that in healthy cells, Bax and Bak activate Mfn2 by promoting assembly and localization to presumptive fusion sites (Karbowski et al., 2006). Since Bax/Bak colocalize with Mfn2 at mitochondrial fission sites in apoptotic cells (Karbowski et al., 2002; Neuspiel et al., 2005), it is additionally possible that the proapoptotic conformations of Bax and Bak inhibit Mfn2’s fusion activity in dying cells. Subsequent research examined the individual contributions of Bax, which is a cytosolic protein in healthy cells, and the constitutively OMM-associated Bak in the regulation of mitochondrial fusion (Brooks et al., 2007; Hoppins et al., 2011). Using knockout cell lines, it was shown that loss of Bak, but not Bax potently inhibits fragmentation (Brooks et al., 2007). In healthy cells, Bak was shown to interact with both mitofusins. However, upon induction of apoptosis, Bak dissociated from Mfn2, but showed increased association with Mfn1 (Brooks et al., 2007). Direct evidence that Bax is a major cofactor in the mitochondrial fusion reaction was recently provided by Hoppins and coworkers, who showed that physiological concentrations of recombinant, monomeric Bax, as well as cytosolic extracts from wild-type, but not Bax/Bak knockout fibroblast can stimulate mitochondrial fusion in an in vitro assay. Intriguingly, Bax stimulation occurred only when Mfn2 was present on both partners of the fusion reaction, indicating that Bax selectively enhances fusion by transmitochondrial, homotypic Mfn2 complexes (Hoppins et al., 2011). Thus, mitochondrial fragmentation at the onset of apoptosis may at least in part be mediated by depletion of monomeric, cytosolic Bax and resultant inhibition of homotypic Mfn2 complexes (Martinou and Youle, 2011).

2.2 Mitofusin ubiquitination

The PINK1/Parkin ubiquitin pathway (as previously discussed in section 1.5) has been implicated in negative regulation of mitochondrial fusion through proteasomal degradation of the mitofusin proteins (Gegg et al., 2010; Glauser et al., 2011; Rakovic et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 2010). Parkin translocates to depolarized mitochondria to mark them for elimination by macroautophagy (mitophagy) (Narendra et al., 2008). Parkin-dependent mitophagy involves accumulation of the AAA+ (ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities) protein p97 on damaged mitochondria and ubiquitination/proteasomal degradation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 (Tanaka et al., 2010), presumably to aid in the isolation of dysfunctional mitochondria. There appears to be consensus that parkin-dependent mitophagy involves downregulation of both mitofusins; however, degradation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 may occur by different mechanisms. Gegg et al. showed that induction of mitophagy in SH-SY5Y cells promotes PINK1 and parkin-dependent ubiquitination of Mfn1 and Mfn2, but that Mfn1 is more heavily modified (Gegg et al., 2010). A subsequent report demonstrated that parkin interacts with and promotes the degradation of both Mfn1 and Mfn2 in SH-SY5Y cells. However, only Mfn1 was found to be a substrate for parkin-dependent polyubiquitination, while parkin-mediated Mfn2 downregulation was suggested to be ubiquitin independent (Glauser et al., 2011). Lastly, in fibroblasts from control individuals, but not from PD patients with parkin or PINK1 mutations, mitochondrial depolarization promoted both Mfn1 and Mfn2 ubiquitination (Rakovic et al., 2011). These results strongly implicate failure to eliminate dysfunctional mitochondria as the pathogenic mechanism in familial PD with PINK1 or parkin mutations. However, whether mitofusin degradation is causally involved in PINK1/parkin-dependent mitophagy or merely a bystander effect remains to be shown.

2.3 Opa1 proteolysis

Anchored to the IMM and localized mostly in the IMS, Opa1 is thought to function similarly to the mitofusins, first tethering and then fusing opposing IMMs (Olichon et al., 2002). Opa1 is an essential protein as demonstrated by Opa1 knockout and mutant knock-in studies (Landes et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2010; Westermann, 2010). Fusion of the IMM is critical for maintenance of mitochondrial DNA and metabolic function (Chen and Chan, 2010; Jones and Fangman, 1992), and loss of Opa1 results in autophagic elimination of mitochondria (White et al., 2009). Missense mutations in Opa1 cause autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA, Kjer’s disease), the leading cause of hereditary blindness (Delettre et al., 2000; Pesch et al., 2001). In addition to loss of retinal ganglion cells, Opa1 mutations are associated with a variety of secondary neurological defects including deafness, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and myopathy (Amati-Bonneau et al., 2009; Landes et al., 2010; Yu-Wai-Man et al., 2010).

Perhaps owing to Opa1’s residence in the IMS, there is no evidence that Opa1 is regulated by phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or sumoylation like the other dynamin-related proteins involved in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Instead, proteolytic cleavage of Opa1 plays a critical role in the regulation of IMM fusion (Griparic et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007). There are several classes of proteases within the mitochondria, including the rhomboid presenilin-associated rhomboid-like (PARL) proteases, the ATP-dependent matrix AAA (mAAA) proteases and inner membrane space AAA (iAAA) proteases. Although the PARL class was initially identified as having a major role in Opa1 processing (Cipolat et al., 2006), subsequent studies did not support this finding (Griparic et al., 2007).

In 2007, concurrent studies demonstrated a role for the iAAA protease, Yme1, in the cleavage of specific Opa1 splice variants (Griparic et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007). Specifically, Yme1 cleaves Opa1 at two distinct sites located within alternative exons 4b and 5b. Yme1-mediated cleavage is constitutive (Griparic et al., 2007) and generates both a long IMM-bound isoform (fusion capable) and an IMS- localized short, fusion incompetent isoform (Song et al., 2007). During the investigation of Yme1-mediated cleavage, it was noted that proteolysis of Opa1 occurred even in the absence of Yme1 (Griparic et al., 2007; Song et al., 2007). To resolve this, additional screens were performed and concurrent publications demonstrate regulation of Opa1 cleavage by a second IMM bound protease, Oma1 (Ehses et al., 2009; Head et al., 2009). Unlike constitutive cleavage by Yme1, Oma1 is stabilized and/or activated upon loss of membrane potential (Head et al., 2009). A model was put forth in which membrane depolarization associated with apoptosis prevents the degradation of Oma1 by an unknown protease, allowing Oma1 to accumulate and cleave Opa1 in order to facilitate cytochrome c release from the interchristae space (Ehses et al., 2009; Head et al., 2009). However, a recent study found that Opa1 cleavage is induced even when isolated mitochondria are depolarized, conditions that should not allow for accumulation of nucleus-encoded Oma1 in the IMS (Hoppins et al., 2011).

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that fusion of the IMM is finely regulated by both constitutive and inducible proteolytic processing of long and short Opa1 splice variants. Inducible, Oma1-mediated proteolysis of Opa1 likely collaborates with mitofusin degradation (see 2.2) during mitophagy to prevent dysfunctional mitochondria from reintegrating into the network of healthy mitochondria (Twig et al., 2008). However, constitutive Yme1-mediated processing of Opa1 may be an attractive pharmacological target for the treatment of ADOA, especially if Yme1 inhibitors could be designed to specifically increase protein expression from the wild-type Opa1 allele.

3. OMM-localized kinase/phosphatase complexes

3.1 The OMM signaling scaffold AKAP1

A kinase anchoring protein 1 (AKAP1, a.k.a. D-AKAP1, AKAP121, AKAP149) is a multifunctional scaffold protein with an N-terminal transmembrane sequence that confers OMM localization (Affaitati et al., 2003; Cardone et al., 2002; Ginsberg et al., 2003; Slupe et al., 2011). An N-terminal variant that associates with the ER has also been reported (Ma and Taylor, 2008); however, the physiological significance of ER-localized AKAP1 is unclear since this variant is only encoded by the mouse genome. Recruiting the PKA holoenzyme to mitochondria via AKAP1 facilitates Drp1 phosphorylation at SerPKA and subsequent mitochondrial elongation and neuroprotection (Merrill et al., 2011). Additionally, AKAP1 has been shown to bind to two Ser/Thr phosphatases, protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (Rogne et al., 2009) and CaN (Abrenica et al., 2009). While PP1 has not yet been shown to directly or indirectly dephosphorylate Drp1, OMM-targeted Inhibitor-2, a PP1 inhibitor protein, induces mitochondrial fusion, indicating a role for PP1 in mitochondrial shape regulation (Merrill et al., 2011). CaN promotes Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission by relieving inhibitory phosphorylation of Drp1 at SerPKA (Cereghetti et al., 2008; Cribbs and Strack, 2007). AKAP1 was also reported to associate with other signaling enzymes, including type 4 phosphodiesterase (PDE4), the tyrosine phosphatase PTPD1, and, via PTPD1 the tyrosine kinase Src (Asirvatham et al., 2004; Cardone et al., 2004; Livigni et al., 2006). However, the impact of these relatively poorly characterized associations of AKAP1 on mitochondrial fission/fusion remains to be explored. By degrading cAMP and thus temporally and spatially restricting PKA activation and Drp1 phosphorylation, OMM-targeted PDE4 would be expected to enhance mitochondrial fission. With the ability of AKAP1 to recruit both kinases and phosphatases to their substrates at the OMM, AKAP1 is strategically positioned to integrate multiple signal transduction cascades in the regulation of mitochondrial shape and function (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Signaling complexes at the OMM regulate mitochondrial dynamics. A kinase anchoring protein 1 (AKAP1) recruits in addition to cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), several other signaling enzymes, among them the calcium sensitive protein phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) and protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) to the OMM. The Bβ2 regulatory subunit targets the scaffolding (A) and catalytic (C) subunits of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to the OMM via transient association with receptor components of the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex. Mitochondrial fission factor (Mff) localizes dynamin related protein-1 (Drp1) to the OMM. Drp1 is phosphorylated at SerPKA and inactivated by PKA; dephosphorylation by CaN and PP2A/Bβ2 activates Drp1.

3.2 Outer-mitochondrial PP2A in spinocerebellar ataxia type 12

In neurons, a small, but functionally critical pool of the Ser/Thr phosphatase PP2A is localized to the OMM. PP2A functions as a heterotrimeric complex consisting of a catalytic subunit (C), a scaffold subunit (A) and one of approximately fifteen regulatory subunit (B) derived from four independent gene families (B, B′, B″, and B‴). Substrate specificity of PP2A arises from by number of mechanisms including: localization of the heterotrimeric complex dictated by the B subunit; posttranslational modifications which influence holoenzyme assembly; endogenous inhibitors and activators; weak affinity interactions between the B subunit and target substrates; and, direct interactions between the B subunit and the catalytic cleft of the C subunit (Slupe et al., 2011). The Bβ regulatory subunit is neuron specific. Two splice variants of Bβ, Bβ1 and Bβ2, differ in the inclusion of one of two N-terminal coding exons (Dagda et al., 2003; Schmidt et al., 2002). The unique N-terminal extension of Bβ2 acts as a cryptic mitochondrial import signal that mediates OMM localization of the PP2A holoenzyme via transient interactions with receptor components of the translocase of the outer membrane (TOM) complex (Dagda et al., 2005) (Figure 3). OMM-localization of PP2A/Bβ2 is enhanced following excitotoxic glutamate treatment of hippocampal neurons and other insults, but regulatory mechanisms remain to be explored (Dagda et al., 2008).

SCA type 12 (SCA12) is an autosomal-dominant, progressive ataxia associated with wide-spread cerebral atrophy, which generally manifests in the fourth decade of life. The disease is associated with a trinucleotide (CAG) repeat expansion in a promoter region of PPP2R2B, the gene encoding the Bβ1 and Bβ2 regulatory subunits of PP2A (Holmes et al., 1999). A recent report confirmed the mapping of SCA12 to the PPP2R2B gene in a Japanese kindred, but failed to find a pathological expansion of the CAG repeat (Sato et al., 2010). Thus, SCA12 may not be strictly a trinucleotide repeat disorder, but rather arise from dysregulation of PP2A as its most proximal cause. While no information is available on Bβ1 and Bβ2 expression levels in SCA12 patients, we speculate that the non-coding CAG repeat expansion upregulates Bβ2 expression to increase PP2A activity at the OMM, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation and ultimately neuronal demise. Consistent with this model, overexpression of Bβ2 causes Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission and neuronal cell death, while Bβ2 RNAi promotes mitochondrial elongation and protects hippocampal neurons from ischemic and excitotoxic injury (Dagda et al., 2008).

4. Mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal development and synaptic transmission

4.1 Regulation of mitochondrial transport

Neuronal mitochondria undergo a continuous process of distribution throughout the polarized cell by bidirectional transport (Cai et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 1991; Morris and Hollenbeck, 1993; Pilling et al., 2006; Popov et al., 2005; Zinsmaier et al., 2009). Within both the developing and mature central nervous system, mitochondria are positioned spatially to pre- and postsynaptic sites during periods of high ATP utilization (Attwell and Laughlin, 2001; Fabricius et al., 1993; Hollenbeck and Saxton, 2005; Ly and Verstreken, 2006). In addition, mitochondrial protein translation is required for maintenance of the dendritic arbor (Chihara et al., 2007). Regulation of spatially discrete intracellular calcium fluxes by mitochondria is also critical for neuronal function (Nicholls, 2009). The machinery responsible for the transport of mitochondria is therefore responsive to the needs and state of the cell. The following discussion will focus on the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics during neuronal development and plasticity.

Within neuronal processes, a microtubule highway is established for the transport of mitochondria (Heidemann et al., 1981; Schnapp et al., 1986). Although primarily studied in axons, the dendritic mitochondrial transportation mechanisms utilized by neurons are likely similar. Anterograde mitochondrial movement relies on three kinesin motor proteins, KIF1Bβ, KIF5 and KLP-6, whereas retrograde mitochondrial transport is mediated by the dynein motor complex (Hirokawa and Takemura, 2005; Nangaku et al., 1994; Tanaka et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 1998; Varadi et al., 2004). A number of adaptors proteins are necessary for the anterograde transport of mitochondria. The first of these adaptors to be identified and characterized was the protein milton in Drosophila; two vertebrate orthologs of milton, TRAK1/OIP106 and TRAK2/GRIF1, have since been identified (Beck et al., 2002; Cai et al., 2011; Iyer et al., 2003; Stowers et al., 2002). Milton/TRAK serves as a bridge between mitochondria and the kinesin motor complex to support mitochondrial transport (Brickley and Stephenson, 2011; Glater et al., 2006; Stowers et al., 2002). In addition, milton/TRAK also interacts with the protein miro to promote anterograde transport (MacAskill et al., 2009a). Miro is an OMM associated atypical GTPase composed of a c-terminal membrane targeting domain and two GTPase domains which flank two calcium-binding EF hand domains (Fransson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2005). In the GTP-bound state, miro stably associates with milton, and this interaction is disrupted following hydrolysis of GTP to GDP (MacAskill et al., 2009a). In addition to being necessary for basal mitochondrial transport, miro acts as a calcium responsive switch for mitochondrial transport. Through miro, levels of cytosolic calcium control the rate of mitochondrial transport, with mitochondrial transport arrested in response to increases in cytosolic calcium and recovers following a return to basal cytosolic calcium levels (Macaskill et al., 2009b; Saotome et al., 2008; Wang and Schwarz, 2009; Yi et al., 2004). Two mechanisms for mitochondrial transport arrest by calcium have been proposed (Macaskill et al., 2009b; Wang and Schwarz, 2009). In the model proposed by MacAskill and colleagues, miro binds directly to the kinesin motor complex when intracellular calcium levels are low to support mitochondrial movement, increased cytosolic calcium binds to the EF hand domains of miro which disrupts the miro-kinesin interaction (Macaskill et al., 2009b). This is in contrast to the model submitted by Wang and Schwarz in which calcium–bound miro remains associated with the kinesin motor complex, but disrupts the kinesin-microtubule interaction (Wang and Schwarz, 2009). Additional experimentation is necessary to support or refute either of these models. Regardless of the mechanism, calcium mediated arrest of mitochondrial transport localizes the mitochondria within neuronal processes adjacent to areas of intense synaptic transmission. For additional information on mitochondrial motility and activity-dependent transportation arrest the reader is directed to several recent reviews (MacAskill et al., 2010; MacAskill and Kittler, 2010; Soubannier and McBride, 2009). The miro/milton complex has also been shown to interact with the mitochondrial fission/fusion enzymes. Through modulation of Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission, miro mediates mitochondrial fission in response to elevated cytosolic calcium and mitochondrial elongation when calcium levels are low (Saotome et al., 2008). In addition, the miro/milton complex interacts with PINK1 and overexpression of miro/milton reverses mitochondrial fragmentation associated with PINK1 knock-down (Weihofen et al., 2009).

The miro/milton complex has also been shown to interact with the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2, which promotes mitochondrial transport (Misko et al., 2010). Further, CMT2A2 associated mutations in Mfn2 correlate with a mitochondrial transportation defect independent of Mfn2 fusion activity suggesting a relationship between the mitochondrial transport complex and CMT2A2 (Misko et al., 2010). It is, however, unclear whether formation of the miro/milton::Mfn2 complex directly influences Mfn2 mediated mitochondrial fusion.

The mitochondrial transport machinery also seems to be responsive to kinase signaling cascades. Serotonin signaling through the 5-HT1A receptor increases the velocity of mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons through a signaling pathway that may involve Akt inhibition of GSK3β (Chen et al., 2007). In contrast, dopamine increases and decreases the velocity of mitochondrial transport by signaling through the D1 and D2 receptors, respectively; a process that may also involve the Akt→GSK3β axis (Chen et al., 2008). However, the relevant GSK3β substrates and phosphorylation sites remain to be identified.

4.2 Mitochondrial dynamics in neurite and synapse development

During development mitochondrial transport into neuronal processes supports the formation of dendritic spines and axon branching (Dedov et al., 2000; Li et al., 2004; Morris and Hollenbeck, 1993). A basal level of mitochondrial trafficking into dendrites and axons has been shown to occur independent of synaptic activity, but mitochondrial residency increases in dendrites with increased synaptic activity (Chang et al., 2006). The mechanism of activity dependent mitochondrial residency in dendrites likely involves remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. In response to NMDA receptor activation, down regulation of CDK5 disinhibits mitochondria-associated Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein verprolin homologous protein 1 (WAVE1) which then mediates the localization of mitochondria to developing dendritic spines (protrusions)(Sung et al., 2008). This process likely occurs through WAVE1 activation of the Arp2/3 complex followed by actin polymerization and results in increased dendritic spine density (Kim et al., 2006). In addition, Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission is necessary for activity dependent increase in spine density (Dickey and Strack, 2011; Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2004).

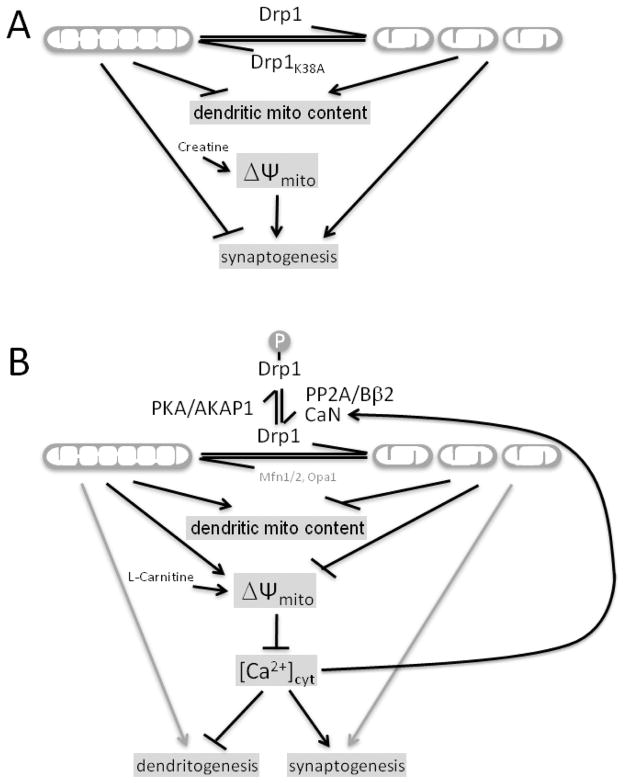

Drp1 is required for development of the mammalian nervous system (Ishihara et al., 2009; Wakabayashi et al., 2009; Waterham et al., 2007). Drp1 deficiency results in depletion of mitochondria from developing neurites, reduced neurite outgrowth and impaired synapse formation (Ishihara et al., 2009). The process of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in neuronal development and plasticity is regulated by phosphorylation of Drp1 at SerPKA. Inactivation of Drp1 by phosphorylation at SerPKA through the actions of PKA/AKAP1 results in a reduction in dendritic spine density and an increase in dendrite outgrowth. PP2A/Bβ2 opposes AKAP1/PKA via Drp1 dephosphorylation at SerPKA (Dickey and Strack, 2011). As PP2A/Bβ2 mRNA is induced during the period of peak synaptogenesis in the developing mammalian nervous system, phospho-regulation of Drp1 may support early synaptogenesis (Dagda et al., 2003). Alterations of morphology directly influence the bioenergetic functions of mitochondria, which likely drive the developmental processes. Through the PKA→Drp1 SerPKA axis, mitochondrial elongation increases ATP generation and mitochondrial membrane potential (Dickey and Strack, 2011; Gomes et al., 2011). It is tempting to speculate that mitochondria are strictly responsible for ATP generation to power neuronal development; however, pharmacological alterations of ATP bioavailability during development has lead to conflicting observations. Li and colleagues found that application of 20 mM creatine, a small molecule which increases the bioavailability of cytosolic ATP (Klein and Ferrante, 2007), to cultured hippocampal neurons increases dendritic spine density (Li et al., 2004). Conversely, our laboratory has observed that when applied to cultured hippocampal neurons, 1 mM L-carnitine, a small molecule, which increases lipid metabolism by mitochondria (Bremer, 1983), reduces density and number of axospinous synapses (Dickey and Strack, 2011). In addition to modulating ATP generation, mitochondrial morphology affects membrane potential dependent mitochondrial calcium sequestration. A reduction of mitochondrial fission following Drp1 inhibition increases calcium sequestration in cortical neurons (Saotome et al., 2008). Conversely, overexpression of Fis1, which results in enhanced mitochondrial fission, reduces calcium uptake (Frieden et al., 2004). Further, pharmacological alteration of calcium availability phenocopies the affect of mitochondrial morphology modulation on dendritogensis with increasing calcium availability decreasing dendritogensis and decreasing calcium availability increasing dendritogensis (Dickey and Strack, 2011) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Regulation of dendritogenesis and synaptogenesis by Drp1. Models put forth by Li et al., 2004 (A), and Dickey and Strack, 2011 (B). While mitochondrial fission promotes synaptogenesis according to both models, model A posits that this involves an increase in dendritic mitochondria (mito) content and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), while the opposite holds in model B. See section 4.2 for details.

A positive feedback loop may exist between phospho-regulation of Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission and alterations of calcium homeostasis. As the calcium-dependent protein phosphatase CaN catalyzes dephosphorylation of SerPKA, it is possible that this pathway of Drp1 phospho-regulation also influences localization of mitochondria and synaptic development/plasticity (Cereghetti et al., 2008; Cribbs and Strack, 2007). Support for this idea arises from the observation that FK506/tacrolimus, a small molecule inhibitor of CaN, represses synaptic plasticity and development (Moriwaki et al., 1996; Onuma et al., 1998). During neuronal development, PP2A/Bβ2-induced mitochondrial fission may decrease mitochondrial calcium sequestration, which could increase CaN-mediated Drp1 SerPKA dephosphorylation leading to further mitochondrial fission (Figure 4).

Association with Bcl-2 family members also influences Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission at the site of the synapse. The anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bcl-xL has been shown to participate in synapse formation through modulation of the mitochondrial fission machinery and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Expression of Bcl-xL is temporally correlated with peak levels of neurogenesis in the developing mammalian nervous system and expression is maintained into adulthood (Krajewska et al., 2002). By injecting recombinant human Bcl-xL into the presynaptic nerve terminals of isolated squid stellate ganglion axons and monitoring the response of the postsynaptic cell, it was found that Bcl-xL enhances synaptic transmission (Jonas et al., 2003). This effect is likely mediated in part through modulation of Drp1. Bcl-xL increases the GTPase activity of Drp1 and presumably Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission, which correlates with increased synaptic mitochondria content and synapse number (Berman et al., 2009; Li et al., 2008). Further, Bcl-xL is also located on the inner mitochondrial membrane where its presence stabilizes the mitochondrial membrane potential increasing the efficiency of ATP production (Chen et al., 2011).

4.3. Mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic bioenergetics

A number of observations do not support a crucial role for mitochondrial localization near synapses in synaptic function. The most compelling evidence generated thus far comes from studies with Drosophila. Verstreken and colleagues observed that when mitochondria are precluded from entry into the motor nerve terminal by mutational inactivation of Drp1, synaptic transmission fidelity is compromised, however this effect is only apparent during periods of high activity; prolonged 10 Hz stimuli (Verstreken et al., 2005). Application of exogenous ATP could partially rescue the motor transmission deficit (Verstreken et al., 2005). Similarly, Stowers and colleagues found that mutational inactivation of milton depletes mitochondria in nerve terminals, but results in a relatively mild neurotransmission phenotype (Stowers et al., 2002). Observations of vertebrate neurons also suggest that mitochondria can fuel synapses from a distance. First, only 40% of presynaptic boutons in the hippocampal CA1 region and virtually no postsynaptic dendritic spines contain mitochondria (Chicurel and Harris, 1992; Li et al., 2004; Shepherd and Harris, 1998). Secondly, physiological absence of mitochondria from hippocampal neuron presynaptic boutons does not correlate with a reduction in synaptic transmission (Waters and Smith, 2003). It is possible that local glycolysis and redistribution of ATP by high energy phosphate carriers adequately supply ATP needs at the synapse thus localized mitochondrial bioenergetic activity is unnecessary for synaptic function at least in neurons with shorter processes (Andres et al., 2008; Linton et al., 2010). In situations where, without localized mitochondrial ATP production, diffusion limited high energy phosphate carriers do not adequately supply ATP needs, synaptic function may degrade. In striated muscle, the diffusion distance over the half-life of phosphocreatine has been estimated at ~66 μm (Gabr et al., 2011). If this finding can be extended to neurons with processes on the order of millimeters in length, it may explain why disruption of the mitochondrial dynamics machinery manifests in neurons with long processes as neuropathies. Indeed, CMT2A2 associated mutations in Mfn2 affect neurons with the longest axons resulting in peripheral neuropathies (Ly and Verstreken, 2006). If mitochondrial derived ATP production is in part dispensable for synaptic function in the central nervous system, it raises a number of questions. Why does a mechanism exist for activity dependent arrest of mitochondrial transport? What function(s) is(are) mitochondria fulfilling near sites of high synaptic activity?

4.4. Mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal calcium homeostasis

Regulation of intracellular calcium is one possible function for mitochondria following transportation arrest near sites of high synaptic activity. The physiological functions of mitochondrial calcium sequestration have been the subject of numerous excellent reviews (Contreras et al., 2010; Nicholls, 2009; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010; Rizzuto, 2001; Rizzuto, 2003). Here we will focus on the intersections between mitochondrial dynamics and calcium homeostasis. The capacity of mitochondria to buffer cytosolic calcium changes is directly related to the proximity of individual mitochondrial to the site of calcium influx (Collins et al., 2001). However, as discussed above, presynaptic nerve terminals and postsynaptic spines are largely devoid of mitochondria and therefore highly localized calcium buffering could be dispensable. In addition, the ability of mitochondria to sequester cytosolic calcium is influenced by mitochondrial fission and fusion. Drp1-driven mitochondrial fission limits mitochondrial calcium uptake and propagation of intramitochondrial calcium waves, and protects HeLa cells from apoptosis induced by ceramide (Szabadkai et al., 2004). Further, it was recently observed that calcium influx through excitatory NMDA receptors induces non-apoptotic cytochrome c release form mitochondria and subsequent activation of caspase-3 is a required step for long-term depression (LTD) (Li et al., 2010). Cytochrome c release by mitochondria is facilitated by Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission, therefore mitochondrial dynamics likely influences LTD (Frank et al., 2001). Also, it has been found that mitochondrial calcium uptake results in ROS mediated long-term potentiation in the spinal cord which may have significance in chronic pain specifically and may represent a novel mechanism of long term potentiation induction generally (Kim et al., 2011). Additional work is certainly necessary to fully characterize the role localized mitochondria play in synaptic function.

5. Mitochondrial dynamics in neuronal survival

The mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery plays a crucial role in the regulated elimination of injured cells through apoptotic and non-apoptotic mechanisms. In addition to bioenergetic and calcium regulatory properties, under homeostatic conditions mitochondria sequester pro-apoptotic cytochrome c within the IMS. In response to injury, release of cytochrome c is an early, necessary step in apoptosis initiation (Goldstein et al., 2000; Li et al., 1997; Zou et al., 1999). Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission facilitates cytochrome c release from mitochondria (Cassidy-Stone et al., 2008; Frank et al., 2001). This process may occur through Drp1-dependent remodeling of the OMM curvature which supports the insertion and oligomerization of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bax into the OMM (Montessuit et al., 2010). The Bax/Bak complex also facilitates Drp1 sumoylation, promoting stable association of Drp1 with the OMM and enhanced Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission (Figueroa-Romero et al., 2009; Wasiak et al., 2007). In neurons, activation of the NMDA receptor in response to glutamate results in both arrested mobility and fragmentation of mitochondria (Rintoul et al., 2003). As the phosphatase CaN is a known mediator of apoptosis following excitotoxic injury and phospho-regulation of Drp1 through SerPKA modulates the pro-apoptotic activity of Drp1, it is possible that the CaN→Drp1 axis may be critical for the execution of neurons following ischemic injury (Cereghetti et al., 2008; Cribbs and Strack, 2007; Wang et al., 1999). In support of this idea, the CaN-mediated Drp1 activation induces apoptosis in cardiomyocytes following ischemia/reprofusion injury (Wang et al., 2010). Also, the neuron specific PP2A/Bβ2 complex increases susceptibility to cell death following ischemic and excitotoxic injury in a Drp1 dependent manner (Dagda et al., 2008). In addition, during neuronal injury, oxidative stress may activate Drp1 via nitrosylation, however as discussed above this finding is controversial and the mechanism is incompletely described (Barsoum et al., 2006; Bossy et al., 2010; Cho et al., 2009). Oxidative stress during neuronal injury may also activate Drp1 via phosphorylation of SerCDK by PKCδ (Qi et al., 2011) (see 1.3). Activation of Drp1 during oxidative stress may, in part, account for neuronal death associated with the abuse of methamphetamine (Tian et al., 2009). In contrast to the pro-apoptotic activity of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission, the activity of the mitochondrial fusion proteins is anti-apoptotic. Mfn2 overexpression or mutational activation is neuroprotective during oxidative stress and attenuates the release of cytochrome c (Jahani-Asl et al., 2007). Loss of Opa1 function by calpain-mediated inactivation is also a pro-apoptotic pathway during excitotoxic injury (Jahani-Asl et al., 2011). For these reasons modulation of the mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery may provide the basis for novel neuroprotective strategies.

As discussed above, the PINK1/Parkin pathway intersects with the mitochondrial fission/fusion machinery at multiple points. Recently, a neuroprotective role for mitochondrial fission following manipulation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway has been suggested. Seminal studies in Drosophila have shown that PINK1and Parkin promote mitochondrial fission through a Drp1-dependent pathway. Further, overexpression of Drp1 or knock-down of mitochondrial fusion promoting proteins can rescue the phenotype of PINK1/Parkin deficiency or mutation (Deng et al., 2008; Park et al., 2009; Poole et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). In line with these Drosophila studies, Yu and colleagues demonstrated that mitochondrial elongation associated with PINK1 knockdown by RNAi correlates with increased susceptibility to excitotoxic cell death in cultured mammalian hippocampal neurons. Conversely, mitochondrial fission associated with overexpression of either Parkin or PINK1 resulted in neuroprotection (Yu et al., 2011). However, since several other studies reported that PINK1 and/or Parkin inactivation in mammalian cells results in mitochondrial fragmentation (Dagda et al., 2009; Dagda et al., 2011; Exner et al., 2007; Lutz et al., 2009; Sandebring et al., 2009), the exact role of the PINK1/Parkin pathway in mitochondrial dynamics remains controversial. In addition, whether the observed neuroprotective effects associated with overexpression of the PINK1 or Parkin are a direct consequence of mitochondrial fission or due to modulation of other cellular processes such as mitophagy (see 2.2) remains to be determined.

6. Implications for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases

A small molecule inhibitor of Drp1, Mdivi-1, has been developed and may potentially find therapeutic utility. Mdivi-1 is a noncompetitive inhibitor of Drp1 GTPase activity and attenuates Drp1 mediated mitochondrial-fission in response to pro-apoptotic stimuli (Cassidy-Stone et al., 2008). Mdivi-1 application in vivo has been shown to preserve kidney function following ischemia and acute kidney injury, protect cardiomyocytes against ischemia/reperfusion injury, and attenuate retinal ganglion cell death after ischemic injury (Brooks et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011). Mdivi-1 also partially rescues the mitochondrial damage due to inactivation of PINK1 (Cui et al., 2010). Further work in the neuroscience field will allow this paradigm, therapeutics aimed at preserving intracellular mitochondrial function for the treatment of disease and injury, to mature and could improve the clinical outlook for neurodegenerative diseases.

Highlights.

Mitochondrial fission/fusion enzymes are regulated by diverse posttranslational modifications

Phosphorylation of the fission enzyme Drp1 regulates neuronal survival and development

Outer-mitochondrial kinase/phosphatases signaling complexes control mitochondrial shape

Spinocerebellar ataxia 12 may involve dysregulated phosphatase signaling at mitochondria

Mitochondrial dynamics impacts bioenergetics and Ca2+ signaling in neurons

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants NS043254, NS056244, and NS057714 (to S.S.) and National Research Service Award Predoctoral Fellowship NS077563 (to A.M.S).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrenica B, AlShaaban M, Czubryt MP. The A-kinase anchor protein AKAP121 is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:674–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affaitati A, Cardone L, de Cristofaro T, Carlucci A, Ginsberg MD, Varrone S, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV, Feliciello A. Essential role of A-kinase anchor protein 121 for cAMP signaling to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4286–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, Rodriguez M, Kellner U, Leo-Kottler B, Auburger G, Bhattacharya SS, Wissinger B. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nature genetics. 2000;26:211–5. doi: 10.1038/79944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amati-Bonneau P, Milea D, Bonneau D, Chevrollier A, Ferre M, Guillet V, Gueguen N, Loiseau D, de Crescenzo MA, Verny C, Procaccio V, Lenaers G, Reynier P. OPA1-associated disorders: phenotypes and pathophysiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1855–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres RH, Ducray AD, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Widmer HR. Functions and effects of creatine in the central nervous system. Brain Res Bull. 2008;76:329–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asirvatham AL, Galligan SG, Schillace RV, Davey MP, Vasta V, Beavo JA, Carr DW. A-kinase anchoring proteins interact with phosphodiesterases in T lymphocyte cell lines. J Immunol. 2004;173:4806–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–45. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum MJ, Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Kushnareva Y, Graber S, Kovacs I, Lee WD, Waggoner J, Cui J, White AD, Bossy B, Martinou JC, Youle RJ, Lipton SA, Ellisman MH, Perkins GA, Bossy-Wetzel E. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. EMBO J. 2006;25:3900–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Brickley K, Wilkinson HL, Sharma S, Smith M, Chazot PL, Pollard S, Stephenson FA. Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of a novel GABAA receptor-associated protein, GRIF-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30079–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard G, Karbowski M. Mitochondrial fusion and division: Regulation and role in cell viability. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:365–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman SB, Chen YB, Qi B, McCaffery JM, Rucker EB, 3rd, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Arnold BA, Jonas EA, Pineda FJ, Hardwick JM. Bcl-x L increases mitochondrial fission, fusion, and biomass in neurons. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:707–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup S, Gerlach M, Kupsch A, Reichmann H, Riederer P, Vieregge P, Wullner U, Gasser T. Genes associated with Parkinson syndrome. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 5):8–17. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-5005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossy B, Petrilli A, Klinglmayr E, Chen J, Lutz-Meindl U, Knott AB, Masliah E, Schwarzenbacher R, Bossy-Wetzel E. S-Nitrosylation of DRP1 does not affect enzymatic activity and is not specific to Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S513–26. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer J. Carnitine--metabolism and functions. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:1420–80. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.4.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickley K, Stephenson FA. Trafficking Kinesin Protein (TRAK)-mediated Transport of Mitochondria in Axons of Hippocampal Neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:18079–18092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:1275–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C, Wei Q, Feng L, Dong G, Tao Y, Mei L, Xie ZJ, Dong Z. Bak regulates mitochondrial morphology and pathology during apoptosis by interacting with mitofusins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703976104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Davis ML, Sheng ZH. Regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport and its impact on synaptic transmission. Neuroscience Research. 2011;70:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Kaliszewski CK, Greer CA. Organization of mitochondria in olfactory bulb granule cell dendritic spines. Synapse. 1991;8:107–118. doi: 10.1002/syn.890080205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone L, Carlucci A, Affaitati A, Livigni A, DeCristofaro T, Garbi C, Varrone S, Ullrich A, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV, Feliciello A. Mitochondrial AKAP121 binds and targets protein tyrosine phosphatase D1, a novel positive regulator of src signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4613–26. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4613-4626.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone L, de Cristofaro T, Affaitati A, Garbi C, Ginsberg MD, Saviano M, Varrone S, Rubin CS, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV, Feliciello A. A-kinase anchor protein 84/121 are targeted to mitochondria and mitotic spindles by overlapping amino-terminal motifs. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:663–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy-Stone A, Chipuk JE, Ingerman E, Song C, Yoo C, Kuwana T, Kurth MJ, Shaw JT, Hinshaw JE, Green DR, Nunnari J. Chemical inhibition of the mitochondrial division dynamin reveals its role in Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Dev Cell. 2008;14:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, de Brito OM, Chang CR, Blackstone C, Bernardi P, Scorrano L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CR, Blackstone C. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Drp1 regulates its GTPase activity and mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21583–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DTW, Honick AS, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial Trafficking to Synapses in Cultured Primary Cortical Neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7035–7045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1012-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Howng SL, Hwang SL, Chou CK, Liao CH, Hong YR. Differential expression of four human dynamin-like protein variants in brain tumors. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:189–94. doi: 10.1089/104454900314573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chan DC. Physiological functions of mitochondrial fusion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1201:21–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Owens GC, Crossin KL, Edelman DB. Serotonin stimulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:472–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Owens GC, Edelman DB. Dopamine Inhibits Mitochondrial Motility in Hippocampal Neurons. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Aon MA, Hsu YT, Soane L, Teng X, McCaffery JM, Cheng WC, Qi B, Li H, Alavian KN, Dayhoff-Brannigan M, Zou S, Pineda FJ, O’Rourke B, Ko YH, Pedersen PL, Kaczmarek LK, Jonas EA, Hardwick JM. Bcl-xL regulates mitochondrial energetics by stabilizing the inner membrane potential. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:263–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicurel ME, Harris KM. Three-dimensional analysis of the structure and composition of CA3 branched dendritic spines and their synaptic relationships with mossy fiber boutons in the rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1992;325:169–82. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chihara T, Luginbuhl D, Luo L. Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial protein translation in axonal and dendritic terminal arborization. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:828–37. doi: 10.1038/nn1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, Nakamura T, Fang J, Cieplak P, Godzik A, Gu Z, Lipton SA. S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates beta-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science. 2009;324:102–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1171091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Mitochondrial dynamics in cell death and neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3435–47. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KW, Kim SB, Park KD, Choi KG, Lee JH, Eun HW, Suh JS, Hwang JH, Kim WK, Seo BC, Kim SH, Son IH, Kim SM, Sunwoo IN, Choi BO. Early onset severe and late-onset mild Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with mitofusin 2 (MFN2) mutations. Brain. 2006;129:2103–18. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolat S, Rudka T, Hartmann D, Costa V, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Metzger K, Frezza C, Annaert W, D’Adamio L, Derks C, Dejaegere T, Pellegrini L, D’Hooge R, Scorrano L, De Strooper B. Mitochondrial rhomboid PARL regulates cytochrome c release during apoptosis via OPA1-dependent cristae remodeling. Cell. 2006;126:163–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang C, Cao JH, Huh JR, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Hay BA, Guo M. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1162–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins TJ, Lipp P, Berridge MJ, Bootman MD. Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Depends on the Spatial and Temporal Profile of Cytosolic Ca2+ Signals. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:26411–26420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras L, Drago I, Zampese E, Pozzan T. Mitochondria: the calcium connection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:607–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs JT, Strack S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:939–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Tang X, Christian WV, Yoon Y, Tieu K. Perturbations in mitochondrial dynamics induced by human mutant PINK1 can be rescued by the mitochondrial division inhibitor mdivi-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11740–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Barwacz CA, Cribbs JT, Strack S. Unfolding-resistant translocase targeting: a novel mechanism for outer mitochondrial membrane localization exemplified by the Bbeta2 regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:27375–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503693200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Cherra SJ, 3rd, Kulich SM, Tandon A, Park D, Chu CT. Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13843–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Gusdon AM, Pien I, Strack S, Green S, Li C, Van Houten B, Cherra SJ, 3rd, Chu CT. Mitochondrially localized PKA reverses mitochondrial pathology and dysfunction in a cellular model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell death and differentiation. 2011 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Merrill RA, Cribbs JT, Chen Y, Hell JW, Usachev YM, Strack S. The spinocerebellar ataxia 12 gene product and protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit Bbeta2 antagonizes neuronal survival by promoting mitochondrial fission. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:36241–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800989200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Zaucha JA, Wadzinski BE, Strack S. A developmentally regulated, neuron-specific splice variant of the variable subunit Bbeta targets protein phosphatase 2A to mitochondria and modulates apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24976–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedov VN, Dedova IV, Armati PJ. Transport of Mitochondria During Axonogenesis. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:549–552. doi: 10.1080/15216540050167115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, Pelloquin L, Grosgeorge J, Turc-Carel C, Perret E, Astarie-Dequeker C, Lasquellec L, Arnaud B, Ducommun B, Kaplan J, Hamel CP. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–10. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivani P, Adrain C, Taylor RC, Duriez PJ, Martin SJ. Role for CED-9 and Egl-1 as regulators of mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics. Mol Cell. 2006;21:761–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Dodson MW, Huang H, Guo M. The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:14503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803998105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dephoure N, Zhou C, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Bakalarski CE, Elledge SJ, Gygi SP. A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10762–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bacco A, Ouyang J, Lee HY, Catic A, Ploegh H, Gill G. The SUMO-specific protease SENP5 is required for cell division. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4489–98. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02301-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey AS, Strack S. PKA/AKAP1 and PP2A/Bbeta2 Regulate Neuronal Morphogenesis via Drp1 Phosphorylation and Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15716–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3159-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehses S, Raschke I, Mancuso G, Bernacchia A, Geimer S, Tondera D, Martinou JC, Westermann B, Rugarli EI, Langer T. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1023–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eura Y, Ishihara N, Yokota S, Mihara K. Two mitofusin proteins, mammalian homologues of FZO, with distinct functions are both required for mitochondrial fusion. J Biochem. 2003;134:333–44. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner N, Treske B, Paquet D, Holmstrom K, Schiesling C, Gispert S, Carballo-Carbajal I, Berg D, Hoepken HH, Gasser T, Kruger R, Winklhofer KF, Vogel F, Reichert AS, Auburger G, Kahle PJ, Schmid B, Haass C. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:12413–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius C, Berthold CH, Rydmark M. Axoplasmic organelles at nodes of Ranvier. II Occurrence and distribution in large myelinated spinal cord axons of the adult cat. J Neurocytol. 1993;22:941–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01218352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faelber K, Posor Y, Gao S, Held M, Roske Y, Schulze D, Haucke V, Noe F, Daumke O. Crystal structure of nucleotide-free dynamin. Nature. 2011;477:556–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Romero C, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Stadler J, Chang CR, Arnoult D, Keller PJ, Hong Y, Blackstone C, Feldman EL. SUMOylation of the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 occurs at multiple nonconsensus sites within the B domain and is linked to its activity cycle. FASEB J. 2009;23:3917–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MG, Jenni S, Nunnari J. The crystal structure of dynamin. Nature. 2011;477:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends in molecular medicine. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:515–25. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson A, Ruusala A, Aspenstrom P. Atypical Rho GTPases have roles in mitochondrial homeostasis and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6495–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden M, James D, Castelbou C, Danckaert A, Martinou JC, Demaurex N. Ca(2+) homeostasis during mitochondrial fragmentation and perinuclear clustering induced by hFis1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22704–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabr RE, El-Sharkawy AM, Schar M, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. High-energy phosphate transfer in human muscle: diffusion of phosphocreatine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C234–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00500.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandre-Babbe S, van der Bliek AM. The novel tail-anchored membrane protein Mff controls mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2402–12. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegg ME, Cooper JM, Chau KY, Rojo M, Schapira AH, Taanman JW. Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4861–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MD, Feliciello A, Jones JK, Avvedimento EV, Gottesman ME. PKA-dependent binding of mRNA to the mitochondrial AKAP121 protein. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:885–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glater EE, Megeath LJ, Stowers RS, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria requires milton to recruit kinesin heavy chain and is light chain independent. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:545–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]