Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) is an inflammatory dermatitis that is often misdiagnosed as infectious cellulitis due to its similarity in presentation. Misdiagnosis leads to delay of correct treatment and inappropriate use of antibiotics.

METHODS:

A case series of eosinophilic cellulitis and a literature review are presented.

RESULTS:

Patients with Wells’ syndrome may present with a variety of nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, arthralgia and malaise, as well as myriad cutaneous lesions with associated erythema, presenting as blisters, bullae, papules and/or nodules. Several treatment modalities have been used to treat eosinophilic cellulitis and have been met with variable success rates; these include systemic corticosteroids, topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, with success rates of 91.7%, 50% and 25%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

A high degree of clinical suspicion must be exercised to diagnose this rare condition. Cellulitis with an atypical presentation or not responding to appropriate antibiotic treatment should trigger suspicion of Wells’ syndrome. To date, the most successful treatment method is a short course of systemic corticosteroids.

Keywords: Cellulitis, Eosinophilia, Eosinophilic cellulitis, Flame figures, Wells’ syndrome

Abstract

INTRODUCTION :

La cellulite à éosinophiles (syndrome de Wells) est une dermatite inflammatoire souvent diagnostiquée à tort comme une cellulite infectieuse en raison de sa présentation similaire. Le mauvais diagnostic retarde le traitement pertinent et suscite une utilisation inadéquate des antibiotiques.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les auteurs présentent une série de cas de cellulite à éosinophiles et une analyse bibliographique.

RÉSULTATS :

Les patients ayant le syndrome de Wells peuvent présenter divers symptômes non spécifiques, tels que la fièvre, l’arthralgie et les malaises, de même qu’une myriade de lésions cutanées associées à un érythème, sous forme de vésicules, de cloques, de papules ou de nodules. Plusieurs modalités thérapeutiques ont été utilisées pour traiter la cellulite à éosinophiles et ont obtenu des taux de succès variés. Ainsi, les corticoïdes systémiques, les corticoïdes topiques et les antihistaminiques ont obtenu des taux de succès de 91,7 %, de 50 % et de 25 %, respectivement.

CONCLUSIONS :

Il faut un fort degré de présomption clinique pour diagnostiquer cette maladie rare. La cellulite ayant une présentation atypique ou qui ne répond pas à une antibiothérapie convenable devrait soulever la possibilité de syndrome de Wells. Jusqu’à présent, la méthode thérapeutique la plus réussie consiste à administrer un court traitement aux corticoïdes systémiques.

Wells’ syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described by Dr GC Wells in 1971 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophila (1). It is a rare inflammatory dermatitis, with fewer than 200 cases reported in the literature. Clinically, it resembles bacterial cellulitis because patients usually present with a warm erythematous skin lesion. A seemingly common case of cellulitis with unclear source of infection on history, waxing and waning erythema of the skin, and a lack of response to antibiotic treatment should lead the physician to consider the diagnosis of Wells’ syndrome. The diagnosis is corroborated by histopathological findings that include dermal edema, eosinophilic dermal infiltration and free eosinophilic granules coating collagen bundles (‘flame figures’).

In the present article, we review the literature and identify 32 idiopathic cases of this condition. Using these data, we created an algorithmic approach to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of Wells’ syndrome. We also present our experience with two cases of eosinophilic cellulitis that were successfully treated with oral steroids. The present review is intended to increase awareness of Wells’ syndrome, and to aid in diagnosis and treatment of this uncommon condition.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A healthy 23-year-old man presented with an acute onset of pruritic erythematous plaques, swelling and blistering of his right forearm (Figures 1 and 2). He experienced minimal pain, which was exacerbated with flexion and extension of his hand. He was afebrile (temperature is considered to be a vital sign), with vital signs within normal limits. He denied any history of trauma, recent travel, insect bites or intravenous drug use. A complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count within the normal range (7.88×109/L [normal 4.00×109/L to 10.00×109/L]); however, an elevated C-reactive protein level (6.3 mg/L [normal 0 mg/L to 5.0 mg/L]) was found, suggesting an inflammatory process. The patient was admitted with presumed bacterial cellulitis and was started on a course of intravenous cefazolin. The swelling and skin erythema further progressed along his right arm; thus, antibiotic coverage was broadened. At this time, the plastic surgery service was consulted to rule out necrotizing fasciitis. The diagnoses seemed unlikely given the clinical picture and conservative management with close observation.

Figure 1).

Diffuse erythematous plaque of the right forearm

Figure 2).

Swelling of the right forearm

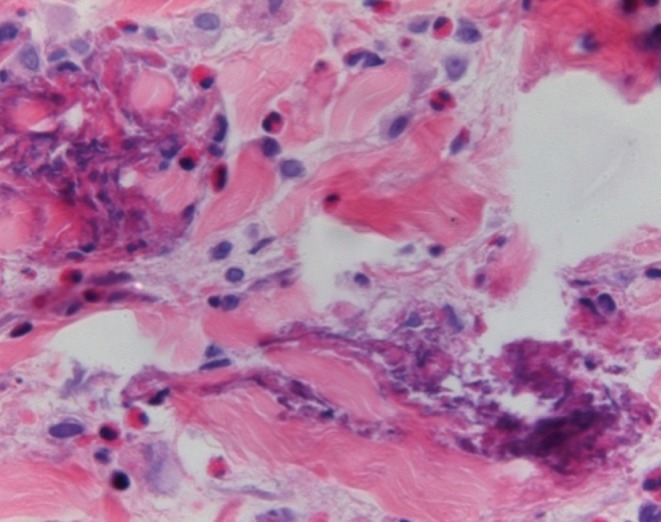

Over the next several hours, the patient remained well, and the erythema of his right arm began to spontaneously improve, regressing from his shoulder down to his forearm. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the right arm demonstrated swelling limited to the subcutaneous tissue. A skin biopsy was performed and pathological findings consistent with Wells’ syndrome were present (Figure 3). The complete blood count revealed peripheral eosinophilia, with a peak of 2.57×109/L (normal 0.10×109/L to 0.50×109/L). With the diagnosis of Wells’ syndrome made from histology, all antibiotic treatment was discontinued, and the patient was treated with a course of oral steroids, which successfully resolved the patient’s symptoms.

Figure 3).

Skin biopsy taken from the patient’s right forearm. Flame figures, dermal edema and dermal infiltration by eosinophils consistent with Wells’ syndrome. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×200

Case 2

A healthy 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of a painful 20 cm × 15 cm, pruritic, mildly tender, brown-violet nodular patch on her right thigh. The patient reported that the lesion had been enlarging over the 10 days before her presentation. The patient was diagnosed with bacterial cellulitis and was admitted to hospital for a course of intravenous antibiotics (cefazolin) as well as close observation. Over the following two days, the erythema continued to progress despite antibiotic treatment. Her white blood cell count was within normal limits (7.50×109/L). The plastic surgery service was consulted, and open fascial biopsies were performed at two different levels to rule out necrotizing fasciitis. Biopsies sent for frozen section showed no significant inflammatory changes in either specimen and a definitive diagnosis could not be made.

Throughout her course in hospital, the patient remained afebrile and cultures did not yield any bacterial growth. A CT scan of the patient’s thigh was unremarkable. Due to the unusual history and presentation, absence of response to antibiotics and a nondiagnostic fascial biopsy, a skin biopsy was performed. A diagnosis of eosinophilic cellulitis was made based on histology. All antibiotic treatments were discontinued and the patient was subsequently treated with a course of oral steroids with successful resolution of the symptoms.

LITERATURE REVIEW

All published data regarding idiopathic Wells’ syndrome from 1950 to 2010 were reviewed. The PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE database Embase were searched using the keywords “eosinophilic cellulitis” and “Wells’ syndrome”. Results were limited to English publications and to reports with adequate information on patient age, sex, symptoms, histological findings, blood counts and detailed treatment. The treatment data were analyzed, and success rates defined as complete resolution of symptoms were determined for each different treatment modality.

RESULTS

The search yielded 32 cases of idiopathic eosinophilic cellulitis, including the two cases described in the present review (2–29) (Table 1). There were 12 (37%) men and 20 (63%) women, with six (19%) cases reported in children. The mean (± SD) age was 33.6±22.5 years. Each of the cases presented with large erythematous plaques whereas only certain patients exhibited blisters (six of 32 [19%]), bullae (11 of 32 [34%]), papules (seven of 32 [22%]) and nodules (five of 32 [16%]). Seven of the 32 patients presented with systemic symptoms including fever, malaise and/or arthralgia. One-half of the patients exhibited localized lesion(s) (16 of 32 [50%]) and the remaining one-half exhibited diffuse lesions (16 of 32 [50%]). Hematological abnormalities, such as peripheral eosinophilia (20 of 32 [67%]) and leukocytosis (13 of 32 [41%]) were not uniformly present. Histopathological findings, such as ‘flame figures’, present in the majority of cases (96%), edema in the dermis and infiltration of the dermis by eosinophils, present in all 32 cases (100%), are considered to be the gold standard for diagnosis of Well’s syndrome.

TABLE 1.

Idiopathic eosinophilic cellulitis (EC): Literature review

| Author (reference), year | Age, years/sex | Systemic symptoms | Location: local (L) or diffuse (D) | Particular presentation | Blood count (WBC, eosinophils), ×109/L | Histological examination of the dermis | Treatment: (–) Did not relieve symptoms; Partial partially relieved symptoms; (+) relieved symptoms | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present case 1 | 23/male | Yes | Right forearm (L) | Blisters | Normal WBC 7.88 Eosinophilia 2.57 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibiotics (penicillin, clindamycin, vancomycin and cefazolin) (+): Oral steroids |

N/A |

| Present case 2 | 44/female | No | Right thigh (L) | Brown-violet nodular | Normal WBC 7.50 Eosinophilia 0.20 (2.7%) |

N/A | (–): Antibiotics (cefazolin, vancomycin, imipenem) (+): Oral steroids |

No recurrence at 6 months |

| Howes et al (4), 2008 | 52/female | Yes: lethargy and arthralgia | Trunk, limbs, face (D) | Papules, nodules | Both normal | No flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral hydroxychloroquine 300 mg/day and indomethacin 25 mg | N/A |

| Green et al (9), 2007 | 91/female | No | Both arms (L) | Bullae | Normal WBC 11.0 Eosinophilia 1.8 (16.4%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisone) and anti-histamine (cetirizine) | N/A |

| Arca et al (7), 2007 | 20/male | Both arms, both feet (L) | Bullae | Leukocytosis 15.0 Normal eosinophils 0.2 (1.3%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisolone 60 mg/day) and antibiotics (Tetracycline) | No recurrences for EC, but developed eosinophilic pustular folliculitis 2 months after | |

| Van der Straaten et al (10), 2006 | 6/male | Yes: febrile | Both legs (L) | Blisters | Leukocytosis 21.5 Eosinophilia 4.2 (20%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Rest and ibuprofen (+): Spontaneously |

Recurrence after 6 months |

| Feliciani et al (11), 2006 | 88/female | N/A | Trunk, abdomen, lower limbs, arms (D) | Bullae | Both normal | Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisolone 40 mg/day) | No recurrences in 3-year follow-up |

| Gilliam et al (12), 2005 | 1/female | No | Lower limbs, left arm (L) | Bullae | Leukocytosis 30.0 Eosinophilia 14.4 (48%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibody (oxacillin) (+): Oral steroid 2 mg/kg combined with topical steroids (triamcinolone) |

No recurrences in 1-year follow-up |

| Ling et al (13), 2002 | 45/female | No | Chest, abdomen, ankle (D) | Bullae | Leukocytosis 13.3 Eosinophilia 6.18 |

No flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Topical corticosteroids (+): Oral steroid (Prednisolone 30 mg daily) and anti-histamine (certirizine) |

No recurrences in 1-year follow-up |

| Ling et al (13), 2002 | 24/male | No | Limbs, trunk, ears and scalp, hands, involved also tongue and throat (D) | Bullae | Both normal | Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisolone 40 mg daily) | N/A |

| Holme et al (14), 2001 | 39/male | No | Both hands, both legs (L) | Nodules, blisters | WBC N/A Eosinophilia 0.7 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibiotics (flucloxacillin, azithromycin) (+): Topical steroids (betamethasone valerate 0.1%) |

N/A |

| Herr and Koh (2), 2001 | 25/male | N/A | Lower abdomen (L) | Nodules | Both normal | Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Oral steroids (prednisolone) Partial: antibiotics (minocycline) and topical steroids (triamcinolone) (+): Cyclosporine 100 mg/day |

No recurrences in 10 months follow-up |

| Herr and Koh (2), 2001 | 42/male | N/A | Right lower abdomen (L) | None | Leukocytosis 12.2 Eosinophilia 3.49 (28.6%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Dapsone, anti-histamine (certirizine) and topical steroids (+): Cyclosporine (100 mg/day) |

No recurrences in 1 year follow-up |

| Weiss et al (15), 2001 | 17/female | No | Lower extremities, back, chest, abdomen (D) | Papules | Normal WBC 8.0 Eosinophils (N/A) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (Prednisolone 40 mg/day) | N/A |

| Selvaag et al (16), 2000 | 43/female | Yes: Febrile and malaise | Face (L) | Papules, nodules | WBC (N/A) Normal eosinophils 0.46 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids 30 mg/daily | N/A |

| Aroni et al (17), 1999 | 12/female | No | Both legs (L) | Papules | WBC (N/A) Eosinophilia (no value) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Anti-histamine (certirizine 10 mg 3×/day) | No recurrences in 1 year follow-up |

| Espana (18), 1999 | 24/female | No | Right foot and both arms (L) | Blisters | Leukocytosis 21.0 Eosinophilia 9.45 (45%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (Prednisone 30 mg/day), dapsone 100 mg/day | Recurrences after 15 months |

| Ferreli et al (19), 1999 | 49/female | No | Both arms (L) | None | Both normal | Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Topical corticosteroid | Recurrences after 2 months with a 1 year follow-up |

| Stam-Westerveld et al (3), 1998 | 75/female | No | Hands, wrists, face, lower legs (D) | Blisters | Normal WBC 7.9 Eosinophilia 1.57 (19.7%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Antibiotics (Minocycline 100 mg/day) | Recurrences after 1 month with a 9-month follow-up |

| Diridl et al (6), 1997 | 29/female | N/A | Lower extremities and lower back (D) | None | WBC (N/A) Normal eosinophils 8% |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

Partial: Topical steroids and oral steroids (+) prolonged PUVA therapy (Psoralen + UVA) |

Recurrences after 7 months |

| Tassava et al (20), 1997 | 41/female | No | Forearms, abdomen, upper thighs (D) | Bullae | Normal WBC 9.3 Eosinophilia 1.0 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

Partial: Topical steroid and antibiotic (+): Oral steroid (prednisone 60 mg/day) |

N/A |

| Garty et al (21), 1997 | Newborn/female | No | Scalp, trunk, legs and dorsal feet, right abdomen (D) | Nodules, bullae | Leukocytosis 15.0 Eosinophilia 3.7 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibiotic, topical steroid (+): Spontaneously |

Recurrences after 18 months |

| Lee and Nixon (23), 1994 | 56/female | No | Abdomen, back (D) | None | Normal WBC 6.6 Normal eosinophils 1% |

Flame figures No edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Topical steroids (–): Anti-histamine (+): Oral steroids (prednisolone 25 mg/day) combined with anti-histamine (acyphroheptadine, cetrizine) Dapsone was given, which allowed lowering the dose of prednisolone |

No recurrence |

| Goh (24), 1992 | 25/male | No | Face, arms, legs (D) | None | Normal WBC 8.5 Eosinophilia 15% |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisone 30 mg/day) | Recurrences after 6 months |

| Coldiron and Robinson (25), 1989 | 25/female | No | Face (L) | Bullae | WBC, N/A Normal eosinophils 8% |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibiotics (+): Topical steroids and oral steroids (prednisone) (+): Was given continuous low-dose prednisone (5mg/day) |

Recurrences 2 times/year in a 4-year follow-up |

| Newton and Greaves (26), 1988 | 39/female | No | Hand, axillae and groins, limbs (D) | Papules | Leukocytosis, No value Eosinophilia 1.2 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Dapsone (+): Oral steroids (Prednisolone 20 mg/day) |

Recurrences (no follow-up time) |

| Horn et al (8), 1985 | 36/female | N/A | Both wrist and thighs (D) | None | Leukocytosis 15.0 Eosinophilia 0.75 (5%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(+): Oral steroids (prednisone 20 mg/day) | Recurrences after 2 years |

| Wong et al (27), 1984 | 28/male | No | Left arm and both limbs and feet (D) | None | Leukocytosis 16.2 Eosinophilia 2.92 (18%) |

Flame figures No edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antihistamine, NSAID, antibiotics (+): Oral steroid (prednisolone 40 mg/day) |

No recurrences (no follow-up time) |

| Saulsbury et al (28), 1983 | 7/male | Yes, febrile | Right upper eyelid, right side of the face, right hand, forearm (D) | Blisters | Leukocytosis 17.7 Eosinophilia 8.50 (48%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Antibiotics (ampicilin) (+): Spontaneously |

Recurrences after 2 months and after 6 months |

| Neilsen et al (29),1981 | 11/male | Yes: febrile and arthralgia | Face, abdomen, upper extremities (D) | Papules, bullae | Leukocytosis 14.8 Eosinophilia 2.78 |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

Partial: Prednisone (80 mg/day) (+): Spontaneously |

No recurrence (no follow-up time) |

| Marks (5), 1980 | 28/female | Yes, febrile | Trunk and limbs (D) | None | Normal WBC 10.5 Eosinophilia 1.16 (11.0%) |

Flame figures Edema Eosinophilic infiltration |

(–): Griseofulvin (+): Dapsone 200 mg/day |

Recurrences after 3 weeks in a 4-month follow-up |

N/A Not available; NSAID Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PUVA Psoralen with ultraviolet A; WBC White blood cell

Multiple modalities have been used to treat Wells’ syndrome with variable success. Oral steroids achieved the highest resolution rate (12 of 13 [92%]), whereas topical corticosteroids (three of six [50%]), and antihistamines (one of four [25%]) were met with less success. Four cases showed spontaneous clearance of lesions (four of 32 [12.5%]). Successful combination treatments have included oral steroids combined with antihistamines, and oral steroids combined with topical steroids. Antibiotics have been generally shown to be ineffective, although the use of minocycline resolved symptoms in one case (n=1) (2,3). Other reported therapies that have shown some success on a smaller scale include antimalarial drugs (n=1) (4), cyclosporine (n=2) (2), dapsone (n=1) (5), psoralen with ultraviolet A therapy (n=1) (6) and oral steroids combined with antibiotics (n=2) (7,8). The natural history of Wells’ syndrome includes recurrence, which occurred in 13 of 23 cases (56%) at a mean follow-up time of 11±8 months.

DISCUSSION

Based on the case reports reviewed, Wells’ syndrome is often mis-diagnosed and, thus, inappropriately treated. As such, the diagnosis of eosinophilic cellulitis should be part of the differential diagnosis for any cellulitis presenting with atypical features (Table 2). The natural course of disease can be divided into two stages. Initially, it presents as burning or pruritus, as well as localized or diffuse cutaneous erythematous plaques. These lesions are mildly tender, with patients subsequently developing cutaneous edema. In addition to erythema, papules, nodules, blisters or bullae may occur. The second stage is characterized by a progressive involution of the lesions, which occurs over a period of two to eight weeks (7), and can result in morphea-like residual skin atrophy and hyperpigmentation (12).

TABLE 2.

Differential diagnosis (DDx) of eosinophilic cellulitis

| DDx | Clinical findings | Histological findings | Standard treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wells’ syndrome (Eosinophilic cellulitis) | Pruritus or burning sensation | Eosinophilic infiltration of dermis | Oral steroids, characteristically unresponsive to antibiotics |

| Erythematous plaques | Flame figures | ||

| +/– Peripheral eosinophilia | Dermal edema | ||

| No tenderness | Absence of vasculitis | ||

| Bacterial cellulitis | Erythematous plaque | Nonspecific neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltrate | Oral or intravenous antibiotics |

| Tenderness | Dermal edema | ||

| Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis) | ANCAs (<50% of cases) | Vasculitis | Oral steroids (with or without chemotherapy [cyclophosphamide]), with addition of steroid-sparing agents for maintenance |

| Peripheral eosinophilia | Flame figures (+/–) | ||

| Palpable purpura | Extravascular granulomas | ||

| Systemic involvement (cardiac, renal and GI) | Eosinophilic infiltration of dermis | ||

| Compartement syndrome | Pain | Fibrocytic activity (remodelling) | Fasciotomy |

| Pallor | Dermal edema | ||

| Swelling | Lymphocytic infiltration of dermis | ||

| Paraesthesia | |||

| Erythema | |||

| Tense compartment | |||

| Elevated compartment pressure | |||

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Tenderness | Necrosis of superficial fascia | Surgical debridement |

| High fever | Polymorphonuclear infiltration of dermis and fascia | Intravenous antibiotics | |

| Erythema and edema of skin followed by necrotic tissue formation | Fibrinous thrombi or arteries and veins coursing through the fascia | ||

| Blisters (+/–) | Microorganisms within destroyed fascia and dermis |

(+/–) Absent/present; ANCA Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; GI Gastrointestinal

Once the diagnosis of Wells’ syndrome is suspected based on clinical findings, it is corroborated by histopathological examination of a skin biopsy specimen. Histological findings vary depending on the time when the biopsy is taken; they are divided into three chronological stages (30). First, the acute stage is marked by dermal infiltration of granulocytes, predominantly eosinophils, and by dermal edema. Second, the subacute stage is characterized by the formation of palisading groups of eosinophils and histiocytes surrounding a core of collagen containing free eosinophilic granules and cellular debris, also known as flame figures. The final (resolution) stage shows gradual disappearance of the eosinophils, leaving histiocytes and giant cells surrounding the flame figures and forming granulomas. Vasculitis is not a feature of Wells’ syndrome (13). Flame figures, while distinctive, are not pathognomic of Wells’ syndrome, and may also be found in Churg-Strauss syndrome, parasitic infections, follicular mucinosis, herpes gestationis (20) and spider bites (10). As such, a clinical and histopathological correlation is necessary for diagnosis.

Although many theories have been proposed, the etiology of Wells’ syndrome remains unknown. Some authors implicate specific triggers in the development of the syndrome, such as insect bites, viral or bacterial infections, drug eruption and thimerisol-containing vaccines (13,31–34). Others have suggested links with hematological disorders, lymphoproliferative malignancies and carcinoma (1,8,35). Although most of the reported cases suggest a triggering event or an underlying disorder, some do not and appear to be idiopathic. The pathogenesis of Wells’ syndrome is also not well defined, with some evidence pointing to a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in response to a variety of exogenous and endogenous stimuli (7).

Many treatments have been used for Wells’ syndrome with variable success. It should be first noted that antibiotic therapy is characteristically ineffective in the treatment of Wells’ syndrome. The most common and effective treatment are oral steroids, most often oral prednisone 2 mg/kg per day for one week, then tapered over two to three weeks. For cases of persistent and frequently recurrent eosinophilic cellulitis, Coldiron et al (25) suggest a therapeutic approach of low-dose (5 mg) alternate-day oral prednisone. Topical corticosteroids also demonstrated efficacy, but should be considered in cases of limited diseases or for residual lesions. There are two cases in the literature of successful treatment of steroid-resistant Wells’ syndrome with low-dose cyclosporine, suggesting the use of cyclosporine for recalcitrant disease (15). Antihistamines can be administered to relieve pruritus (23), but they are ineffective in clearing cutaneous lesions. Dapsone, a medication with both antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, has been used effectively alone and as an adjunct to systemic steroids to spare the negative side effects of long-term high-dose steroid use (23). For cases of eosinophilic cellulitis with an underlying cause, treating the underlying condition has led to resolution of the syndrome, such as treatment of an associated viral infection with acyclovir (33) or an underlying malignancy with radiation therapy (36). Even with appropriate therapy, patients can expect multiple recurrences (31). Using the available evidence (level 4), algorithm 1 (Figure 4) presents a treatment approach, while an approach to the differential diagnosis of eosinophilic cellulitis is presented in algorithm 2 (Figure 5).

Figure 4).

Algorithm 1. Derived for the management of Wells’ syndrome. GI Gastrointestinal; ICP Intracranial pressure; SubQ Subcutaneous. *See Figure 5

Figure 5).

Algorithm 2. Derived for the differential diagnosis of Wells’ syndrome. CBC Complete blood count; H&P History and physical examination

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, the present report represents the most comprehensive literature review to date addressing the diagnosis and management of Wells’ syndrome. This uncommon condition is a cutaneous inflammatory syndrome that runs a benign course, heals with slight hyperpigmentation resembling morphea, and patients have a high probability of recurrence (56%). Wells’ syndrome should be kept in mind as part of the differential diagnosis of any atypical presentation of cellulitis not responsive to antibiotics. Although peripheral eosinophilia is common, this is not sufficient for diagnosis of the syndrome. Correlation of clinical features and histopathological examination of a skin biopsy is necessary to obtain definitive diagnosis. We reviewed published cases of idiopathic eosinophilic cellulitis since 1950 and found that the most successful treatment choice was oral steroids, with a 92% success rate. However, treating the underlying cause is important if one is present and alternate-day low-dose oral steroids is suggested in cases of highly recurrent Wells’ syndrome. Finally, we presented two algorithms to improve diagnostic accuracy and management of this often misdiagnosed condition.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herr H, Koh JK. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) successfully treated with low-dose cyclosporine. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:664–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stam-Westerveld EB, Daenen S, Van der Meer JB. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome): Treatment with minocycline. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:157. doi: 10.1080/000155598433610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howes RL, Girgis, Kossard S. Eosinophilic annular erythema: A subset of Wells’ syndrome or a distinct entity? Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:159–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2008.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks R. Eosinophilic cellulitis – a response to treatment with dapsone: Case report. Australas J Dermatol. 1980;21:10–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1980.tb00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diridl E, Honigsmann H, Tanew A. Wells’ syndrome responsive to PUVA therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:479–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arca E, Köse O, Karslioglu Y. Bullous eosinophilic cellulitis succession with eosinophilic pustular folliculitis without eosinophilia. J Dermatol. 2007;34:80–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn MJ, Katz DA, Bewtra C. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green WH, Yosipovitch G, Pichardo RO. Recurrent, pruritic dermal plaques and bullae. Diagnosis: Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:791–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.6.791-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Straaten S, Wojciechowski M, Salgado R. Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells’ syndrome in a 6-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:197–8. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-0036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feliciani C, Motta A, Tortorella R. Bullous Wells syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1021–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliam AE, Bruckner AL, Howard RM, Lee BP, Wu S, Frieden IJ. Bullous “cellulitis” with eosinophilia: Case report and review of Wells’ syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e149–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ling TC, Antony F, Holden CA. Two cases of bullous eosinophilic cellulitis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:160–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holme SA, McHenry P. Nodular presentation of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:677–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss G, Shemer A, Confino Y, Kaplan B, Trau H. Wells’ syndrome: Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:148–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selvaag E, B. Roald B. Eosinophil activation in Wells’ syndrome demonstrated immunohistochemically with antibodies against eosinophilic cationic protein. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80:63–4. doi: 10.1080/000155500750012630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aroni K, Aivaliotis M, Liossi A, Davaris P. Eosinophilic cellulitis in a child successfully treated with cetirizine. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:332. doi: 10.1080/000155599750010841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.España A, Sanz ML, Sola J, Gil P. Wells’ syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): Correlation between clinical activity, eosinophil levels, eosinophil cation protein and interleukin-5. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:127–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, Aste N. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well’s syndrome): A new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tassava T, Rusonis PA, Whitmore SE. Recurrent vesiculobullous plaques. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome) Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1580–1. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.12.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garty BZ, Feinmesser M, David M, Gayer S, Danon YL. Congenital Wells syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:312–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn HM, Hepburn NC, McLaren KM, Tidman MJ. Recrudescent tumorous eosinophilic cellulitis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:143–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MW, Nixon RL. Eosinophilic cellulitis case report: Treatment options. Australas J Dermatol. 1994;35(2):95–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1994.tb00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goh CL. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:429–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coldiron BM, Robinson JK. Low-dose alternate-day prednisone for persistent Wells’ syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1625–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton JA, Greaves MW. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well’s syndrome) with florid histological changes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:318–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1988.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong E, Greaves MW, O’Brien T. Increased concentrations of immunoreactive leukotrienes in cutaneous lesions of eosinophilic cellulitis. Br J Dermatol. 1984;110:653–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb04700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saulsbury FT, Cooper PH, Bracikowski A, Kennaugh JM. Eosinophilic cellulitis in a child. J Pediatr. 1983;102:266–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen T, Schmidt H, Sogaard H. Eosinophilic cellulitis. (Well’s syndrome) in a child. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:427–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell AJ, Anderson TF, Headington JT, Rasmussen JE. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Wells’ syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb04511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moossavi M, Mehregan DR. Wells’ syndrome: A clinical and histopathologic review of seven cases. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:62–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuttelaar ML, Jonkman MF. Bullous eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) associated with Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:91–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwig RJ, Grundmann-Kollmann M, Holtmeier W, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2-associated eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(5 Suppl):S60–1. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh KJ, Warren L, Moore L, James C, Thompson GN. Wells’ syndrome following thimerisol-containing vaccinations. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:199–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2003.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray D, Eady RA. Migratory erythema and eosinophilic cellulitis associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J R Soc Med. 1981;74:845–7. doi: 10.1177/014107688107401115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HS, Kang MJ, Kim HO, Park YM. Eosinophilic cellulitis in a patient with gastric cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:644–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]