Abstract

Background

Stroke symptoms are common among people without a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack; however, it is unknown if particular attention should be focused on specific symptoms for subgroups of patients.

Methods

Using baseline data from 26,792 REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) participants without a history of transient ischemic attack or stroke, we assessed the association between age, sex, race, current smoking, hypertension and diabetes and the six stroke symptoms in the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-Free Status.

Results

The mean age of participants was 64.4 ± 9.4 years, 40.7% were black and 55.2% women. After multivariable adjustment, older persons more often reported an inability to understand (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16 per 10 years older age, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07–1.25) and unilateral vision loss (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.18) and less often reported numbness (OR=0.83, 95% CI: 0.79–0.87) and weakness (OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.80–0.90). Women reported difficulty communicating more often than men (OR=1.36, 95% CI: 1.19–1.56). The OR for blacks compared to whites for each of the six stroke symptoms was increased, markedly so for unilateral numbness (OR=1.97, 95% CI: 1.81–2.16), unilateral weakness (OR=1.96, 95% CI: 1.76–2.18) and inability to understand (OR=1.87, 95% CI: 1.61–2.18). Current smoking, hypertension, and diabetes were associated with higher ORs for each stroke symptom.

Conclusion

The association of risk factors with six individual stroke symptoms studied was not uniform, suggesting the need to emphasize individual stroke symptoms in stroke awareness campaigns when targeting populations defined by risk.

Keywords: individual stroke symptoms, stroke symptoms, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Stroke symptoms are common among people without a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke 1–3. Evidence is accumulating that stroke symptoms among individuals without a history of TIA or stroke may be indicative of a clinically unrecognized stroke, and important indicators of an increased risk for future stroke events 4–8. However, self-reported stroke symptoms are often neglected by both patients and their physicians. Less than 60% of individuals seek care after having stroke symptoms 4, 9–11. It is possible that particular symptoms may be differentially present and/or reported by subgroups of patients, and this work aims to assess this possibility. Given the powerful predictive ability of stroke symptoms for future stroke events, identifying individuals with a history of stroke symptoms may provide a clinically effective and cost efficient approach for targeting prevention of stroke.

There are several self-report tools available to identify individuals with stroke symptoms 4, 5, 12–14. In general, these tools assess multiple stroke symptoms. Prevalent stroke symptoms have often been considered collectively, with few data available on risk factors for individual symptoms 1, 2, 4. Individual stroke symptoms may represent disruption of flow in different anatomical locations, and different aspects of both cerebrovascular and non-cerebrovascular neurologic disease. As such, risk factors for individual stroke symptoms may differ. Utilizing data from the baseline visit of the population-based REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis to examine the association between risk factors and each of six stroke symptoms among people without a diagnosis of either TIA or stroke. We chose six risk factors to investigate in this analysis: three demographic factors (age, sex, and race) and three highly prevalent and well-established modifiable risk factors for incident stroke (current cigarette smoking, hypertension, and diabetes).

METHODS

Study population

The objective and general design of the REGARDS study has been described elsewhere 15. In brief, the REGARDS study was designed to investigate the causes for the excess stroke mortality in the southeastern US and among blacks compared to whites. Between January 2003 and October 2007, 30,239 black and white US adults ≥ 45 years of age from the continental US were enrolled into the REGARDS study. By design, blacks and residents of the southeastern US were oversampled for inclusion. Potential study participants were sent an introductory letter followed by a telephone call. Those agreeing to participate were administered a telephone interview followed by an in-home study examination conducted by a trained health professional. For the current analysis, we excluded participants with a prior self-reported history of TIA or stroke (n=3,050), or missing data on stroke symptoms (n=397), leaving 26,792 participants in the current analysis. The study methods were approved by Institutional Review Boards at all participating institutions and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

The REGARDS study baseline data were collected through telephone interviews, examinations by health professionals during an in-home study visit, and self-administered questionnaires. Of relevance to the current analysis, the following items were obtained via self-report: age, race, sex, current cigarette smoking, and use of antihypertensive medication, oral hypoglycaemic agents and insulin. During the in-home visit, physical measurements and a blood sample were obtained. With participants in a seated position, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured twice following a standardized protocol. Using the mean of these measurements, hypertension was defined as a SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, or antihypertensive medication use. Diabetes was defined as taking insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, a fasting serum glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL or a non-fasting serum glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL.

During the telephone interview participants were administered the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-free Status (QVSFS) for identifying stroke symptoms 11–13. The QVSFS is a validated questionnaire proposed as a quick screening instrument for identification of stroke-free individuals in the general population with high sensitivity (>80%) and moderate specificity (60%–70%). The six symptoms of stroke specified in the questionnaire are: sudden unilateral painless weakness, sudden unilateral numbness or dead feeling, sudden painless bilateral loss of vision, sudden unilateral loss of vision, sudden loss of ability to understand people, and sudden loss of ability to express oneself in speech or in writing (Appendix) 11.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of study participants were calculated as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, or as counts with percentages for categorical variables. The prevalence of each stroke symptom was calculated by age group (<55, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and ≥ 75 years), race, sex, current cigarette smoking status, and for individuals with and without hypertension and diabetes. The odds ratios for individual stroke symptoms were calculated by logistic regression models. In these models, age was modeled as a continuous variable and region of residence (stroke belt, stroke buckle, other region) was included as a covariate to account for the over-sampling of residents of the southeastern US. The difference in magnitude of the association between each risk factor with each stroke symptom was assessed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an unstructured working correlation matrix. The significance level was set at 0.05. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

The mean age of REGARDS study participants included in this analysis was 64.4 ± 9.4 years, 55.2% were women and 40.7% were black (Table 1). The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and current cigarette smoking were 57.1%, 20.4% and 14.3% respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of REGARDS study participants included in the current analysis.

| Overall (n=26,792) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.4 (9.4) |

| Women | 14,793 (55.2%) |

| Blacks | 10,902 (40.7%) |

| Region of Residence | |

| Stroke Belt | 9,295 (34.7%) |

| Stroke Buckle | 5,628 (21.0%) |

| Non-belt | 11,869 (44.3%) |

| Hypertension | 15,248 (57.1%) |

| Diabetes | 5,291 (20.4%) |

| Current Smoking | 3,805 (14.3%) |

Numbers in table are mean (standard deviation) or n (percent)

Overall, 2758 (10.3%) REGARDS participants in this analysis reported one or more stroke symptom. The prevalence of each stroke symptom is presented overall, and by age, race, sex, and risk factors in Table 2. Sudden unilateral numbness was the most common stroke symptom (8.4%), overall, and within each sub-group investigated. In the overall population, sudden loss of the ability to understand was the least common stroke symptom, reported by 2.6% of participants. This symptom and sudden loss of one half of vision were the least commonly reported symptoms in each of the sub-groups.

Table 2.

Prevalence of individual stroke symptoms among REGARDS study participants.

| Individual stroke symptoms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-group | Unilateral numbness (n=2,243) | Unilateral painless weakness (n=1,543) | Painless loss of vision (n=1,190) | Loss of ability to communicate (n=947) | Loss of one half of vision (n=794) | Loss of ability to understand (n=707) |

| Overall | 8.4% | 5.8% | 4.4% | 3.5% | 3.0% | 2.6% |

| Age, years | ||||||

| <55 | 11.5% | 7.9% | 4.8% | 4.4% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| 55 – 64 | 9.0% | 6.3% | 4.3% | 3.5% | 2.7% | 2.3% |

| 65 – 74 | 7.3% | 4.7% | 4.3% | 3.0% | 3.1% | 2.2% |

| ≥75 | 6.3% | 4.8% | 4.8% | 4.1% | 3.3% | 3.9% |

| Race | ||||||

| Blacks | 11.6% | 8.1% | 4.8% | 4.2% | 3.3% | 3.5% |

| Whites | 6.1% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 3.1% | 2.7% | 2.0% |

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 9.1% | 6.2% | 4.5% | 4.1% | 3.1% | 2.7% |

| Men | 7.5% | 5.2% | 4.3% | 2.9% | 2.8% | 2.6% |

| Current smoker | ||||||

| Yes | 12.6% | 9.0% | 5.9% | 4.9% | 3.6% | 3.7% |

| No | 7.7% | 5.2% | 4.2% | 3.3% | 2.9% | 2.5% |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 9.5% | 6.8% | 4.9% | 3.9% | 3.3% | 3.1% |

| No | 6.9% | 4.3% | 3.9% | 3.0% | 2.6% | 2.1% |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 11.3% | 8.2% | 6.4% | 4.5% | 4.5% | 4.1% |

| No | 7.6% | 5.1% | 3.9% | 3.3% | 2.6% | 2.3% |

Shaded areas indicate that the prevalence is statistically significantly (p<0.05) different in the subgroup for individual stroke symptoms.

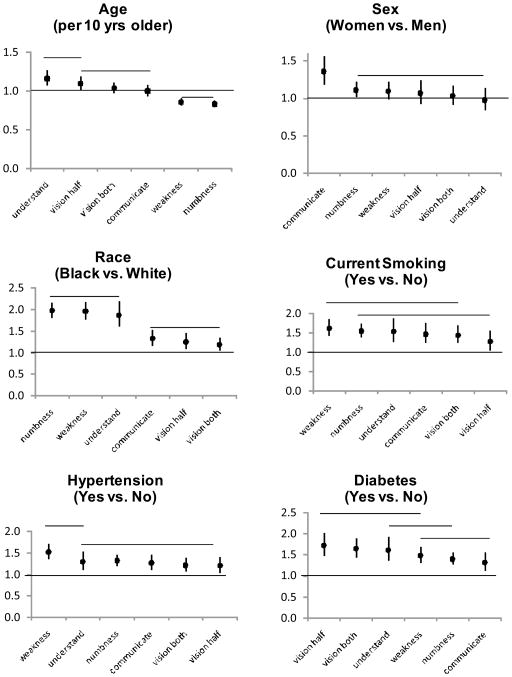

The odds ratios for each stroke symptom associated with demographics and risk factors are presented in Figure 1 with detailed results of the models provided in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. After adjustment for sex, race and region of residence, older age was associated with higher odds ratios for reporting sudden loss of ability to understand and sudden loss of half-vision. In contrast, older age was associated with lower odds ratios for reporting sudden weakness or numbness. The association of female sex with reporting sudden loss of ability to communicate was significantly higher than reporting unilateral numbness, unilateral weakness, loss of half vision, loss of both vision, and loss of ability to understand. The age, sex, and region of residence adjusted odds ratios for blacks compared to whites were significantly increased for all six symptoms with the odds ratios for unilateral numbness, unilateral weakness and loss of ability to understand significantly higher than for the other three stroke symptoms. After adjusting for age, race, sex and region of residence, current smoking, hypertension, and diabetes were associated with increased odds ratios for each of the six stroke symptoms. The magnitude of the odds ratios associated with current smoking and diabetes differed among the stroke symptoms. Smoking had a larger odds ratio for weakness than for the symptom of loss of one-half vision. Hypertension had a larger odds ratio for unilateral weakness than for unilateral numbness, loss of ability to communicate, bilateral loss of vision, and unilateral loss of vision. Diabetes had a larger odds ratio for bilateral loss of vision and unilateral loss of vision than for unilateral numbness and loss of ability to communicate.

Figure 1. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for individual stroke symptoms associated with age, sex, race, current smoking, hypertension, and diabetes.

Stroke symptoms are ordered left-to-right by the decreasing magnitude of the odds ratio and the order of stroke symptoms differs between the panels. Stroke symptoms that are connected by a horizontal line above the graph are not statistically significantly different (p>0.05), while symptoms not covered by a vertical line differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05).

Circles represent odds ratios with vertical lines representing 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Previous studies have noted a high prevalence of stroke symptoms in the general population without a prior diagnosis of stroke or TIA 1, 2. The relationship between demographics and stroke risk factors with individual stroke symptoms has not been well characterized 4. For the current study, we analyzed the association between age, race, sex, current smoking, hypertension and diabetes with six individual stroke symptoms. Blacks, current smokers and those with hypertension and diabetes had increased odds ratios for all six stroke symptoms while older age and female sex were associated with some but not all of the symptoms. Of particular relevance to the current analysis, the magnitude of associations of the risk factors with each of the six stroke symptoms varied.

The prevalence of any stroke symptom was 18% in a prior report from the REGARDS study 2. Additionally, 13% of participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study reported a history of TIA/stroke symptoms 1, 4. In the ARIC study, the odds ratios for any TIA/stroke symptoms were significantly elevated for diabetes mellitus, current smoking, and hypertension, among other risk factors 4. However, risk factors for individual stroke symptoms were not reported. Additionally, our findings are consistent with a prior report from the REGARDS study in that both women and blacks were more likely to report stroke symptoms. However, the current data extend the prior observation by reporting individual stroke symptoms and evaluating the different magnitude on each of the six stroke symptoms associated with both demographics and stroke risk factors.

The report of stroke symptoms may reflect the occurrence of an undiagnosed stroke / subclinical ischemia, or symptoms mistaken as ischemia 16, 17. It is well established that certain populations have lower access to healthcare and, thus despite no report of a prior stroke or TIA, may report stroke symptoms more often. This would not necessarily explain the association between risk factors and some, but not all, stroke symptoms. An alternative explanation is that for persons with certain risk factors, individual stroke symptoms may reflect the occurrence of symptoms that may be misconstrued as ischemia. For example, vision loss (half or complete vision) was more often reported by individuals with diabetes compared to individuals without diabetes. While this finding may reflect undiagnosed stroke, other causes of visual symptoms in this population alternatively explain this finding. Diabetes mellitus commonly causes progressive visual loss due to retinopathy 18 and can cause transient visual loss due to reversible cataracts 19–21 and transient homonymous hemianopsia with non-ketotic hyperglycemia 22.

There have been very few epidemiologic studies on risk factors for stroke symptoms. Two recent studies 23, 24 among hospitalized patients with diagnosed ischemic stroke/TIA reported no significant differences in the prevalence of traditional stroke symptoms between men and women. Our study differs from the previous reports in that the REGARDS study participants self-reported that they were free from stroke and TIA at the time of analysis and were not necessarily seeking care. This implies that there may be a sex difference in the threshold to present for medical care with stroke symptoms or to recognize symptoms as related to stroke, and physicians should be sensitive to the potential that men may be underreporting symptoms related to communication. Likewise we observed black participants were more likely to report all six symptoms (but particularly numbness, weakness and understanding), suggesting that physicians should be particularly aware of these symptoms in blacks, but also sensitivity to the possibility that these symptoms could be underreported in white populations. Finally, prevalent cerebrovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes and smoking) all raised the prevalence of stroke symptoms, suggesting that a higher level of vigilance for the potential stroke symptoms in these populations is likely warranted. Identifying differences in the association between demographics and individual stroke symptoms may help disentangle the higher stroke risk present in some sub-groups of the population.

The high rate of symptoms reported in the REGARDS study suggests individual stroke symptoms may be important to collect in research studies and, perhaps, clinical practice. As noted in the present study, populations known to have a high risk for stroke (e.g., blacks and those with hypertension and diabetes) also report more stroke symptoms. Stroke symptoms increase the risk for stroke 5–8. A recent publication from the REGARDS study indicates that reporting of any of the six stroke symptoms is associated with a 36% increase in stroke risk (hazard ratio = 1.36, 95% CI:1.08 – 1.72) after adjusting for components of the Framingham Stroke Risk Score 8. However, the differential association of individual stroke symptoms with stroke by demographics and risk factors has not been well characterized. For example, in the current study, we found that blacks are more likely than whites to report unilateral numbness, unilateral painless weakness, and the loss of ability to understand. However, the implications of this finding on stroke risk are unclear and depend on the association of these three stroke symptoms with incident stroke. The REGARDS study will be able to test for differences in the relationship between individual stroke symptoms and incident stroke across demographics and stroke risk factors after more stroke events accrue. Such data will be important for guiding the utility of collecting information on stroke symptoms in routine clinical care.

The current analysis should be considered in the context of several potential limitations. Some stroke symptoms may be caused by conditions unrelated to cerebrovascular disease15, 16. While brain imaging for evidence of prior cerebral infarction or an alternative origin for the symptoms may provide insight into the occurrence of stroke symptoms among individuals without self-reported stroke or TIA, this was not available in REGARDS. In addition, we relied on self-report to exclude individuals with stroke and TIA. While the self-reported history of stroke is reasonably accurate 25, there is a potential for misclassification wherein stroke survivors may not remember receiving a diagnosis. The REGARDS study has several strengths, including the large national sample with systematic evaluation of stroke symptoms using a validated questionnaire. In addition, data on risk factors including current smoking, hypertension and diabetes were collected by trained staff using study protocols.

In conclusion, data from the current study suggest that older age, female sex, black race, hypertension, diabetes and current cigarette smoking are not uniformly associated with individual stroke symptoms. These findings suggest that individual stroke symptoms should be emphasized in stroke awareness campaigns.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. Representatives of the funding agency have been involved in the review of the manuscript but not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data.2 The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Toole JF, Lefkowitz DS, Chambless LE, Wijnberg L, Paton CC, Heiss G. Self-reported transient ischemic attack and stroke symptoms: methods and baseline prevalence. The ARIC Study, 1987–1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:849–856. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard VJ, McClure LA, Meschia JF, Pulley L, Orr SC, Friday GH. High prevalence of stroke symptoms among persons without a diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack in a general population: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1952–1958. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leary MC, Saver JL. Annual incidence of first silent stroke in the United States: a preliminary estimate. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:280–285. doi: 10.1159/000071128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambless LE, Shahar E, Sharrett AR, Heiss G, Wijnberg L, Paton CC, et al. Association of transient ischemic attack/stroke symptoms assessed by standardized questionnaire and algorithm with cerebrovascular risk factors and carotid artery wall thickness. The ARIC Study, 1987–1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:857–866. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambless LE, Toole JF, Nieto FJ, Rosamond W, Paton C. Association between symptoms reported in a population questionnaire and future ischemic stroke: the ARIC study. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23:33–37. doi: 10.1159/000073972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vermeer SE, Hollander M, van Dijk EJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2003;34:1126–1129. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000068408.82115.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart CL, Hole DJ, Smith GD. The relation between questions indicating transient schaemic attack and stroke in 20 years of follow up in men and women in the Renfrew/Paisley Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55:653–656. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.9.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleindorfer D, Judd S, Howard V, McClure L, Safford M, Cushman M, et al. Self-reported stroke symptoms without a prior diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack - a powerful new risk factor for stroke. Stroke. 2011 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612937. Epub ahead of print, Sept 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard VJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, McClure LA, Howard G, Wagner L, et al. Care seeking after stroke symptoms. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:466–472. doi: 10.1002/ana.21357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barr J, McKinley S, O’Brien E, Herkes G. Patient recognition of and response to symptoms of TIA or stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:168–75. doi: 10.1159/000091659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles MF, Flossman E, Rothwell PM. Patient behavior immediately after transient ischemic attack according to clinical characteristics, perception of the event, and predicted risk of stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:1254–1260. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217388.57851.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones WJ, Williams LS, Meschia JF. Validating the Questionnaire for Verifying Stroke-Free Status (QVSFS) by neurological history and examination. Stroke. 2001;32:2232–2236. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.096191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meschia JF, Brott TG, Chukwudelunzu FE, Hardy J, Brown RD, Jr, Meissner I, et al. Verifying the stroke-free phenotype by structured telephone interview. Stroke. 2000;31:1076–1080. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung VW, Johnson N, Granstaff US, Jones WJ, Meschia JF, Williams LS, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of Stroke Symptom Questions to Detect Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:100–104. doi: 10.1159/000323951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–43. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nentwich L, Ulrich AS. High-risk chief complaints II: disorders of the head and neck. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:713–746. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amort M, Fluri F, Schafer J, Weisskopf F, Katan M, Burow A, et al. Transient Ischemic Attack versus Transient Ischemic Attack Mimics: Frequency, Clinical Characteristics and Outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:57–64. doi: 10.1159/000327034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet. 2010;376:124–136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler PA. Reversible cataracts in diabetes mellitus. J Am Optom Assoc. 1994;65:559–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelvin JB, Thonn VA. The formation and reversal of acute cataracts in diabetes mellitus. J Am Optom Assoc. 1993;64:471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickey JB, Daily MJ. Transient posterior subcapsular lens opacities in diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:234–238. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taban M, Naugle RI, Lee MS. Transient homonymous hemianopia and positive visual phenomena in patients with nonketotic hyperglycemia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:845–847. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart-Shor EM, Wellenius GA, DelloIacono DM, Mittleman MA. Gender differences in presenting and prodromal stroke symptoms. Stroke. 2009;40:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lisabeth LD, Brown DL, Hughes R, Majersik JJ, Morgenstern LB. Acute stroke symptoms: comparing women and men. Stroke. 2009;40:2031–2036. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.546812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engstad T, Bonaa KH, Viitanen M. Validity of self-reported stroke : The Tromso Study. Stroke. 2000;31:1602–1607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.